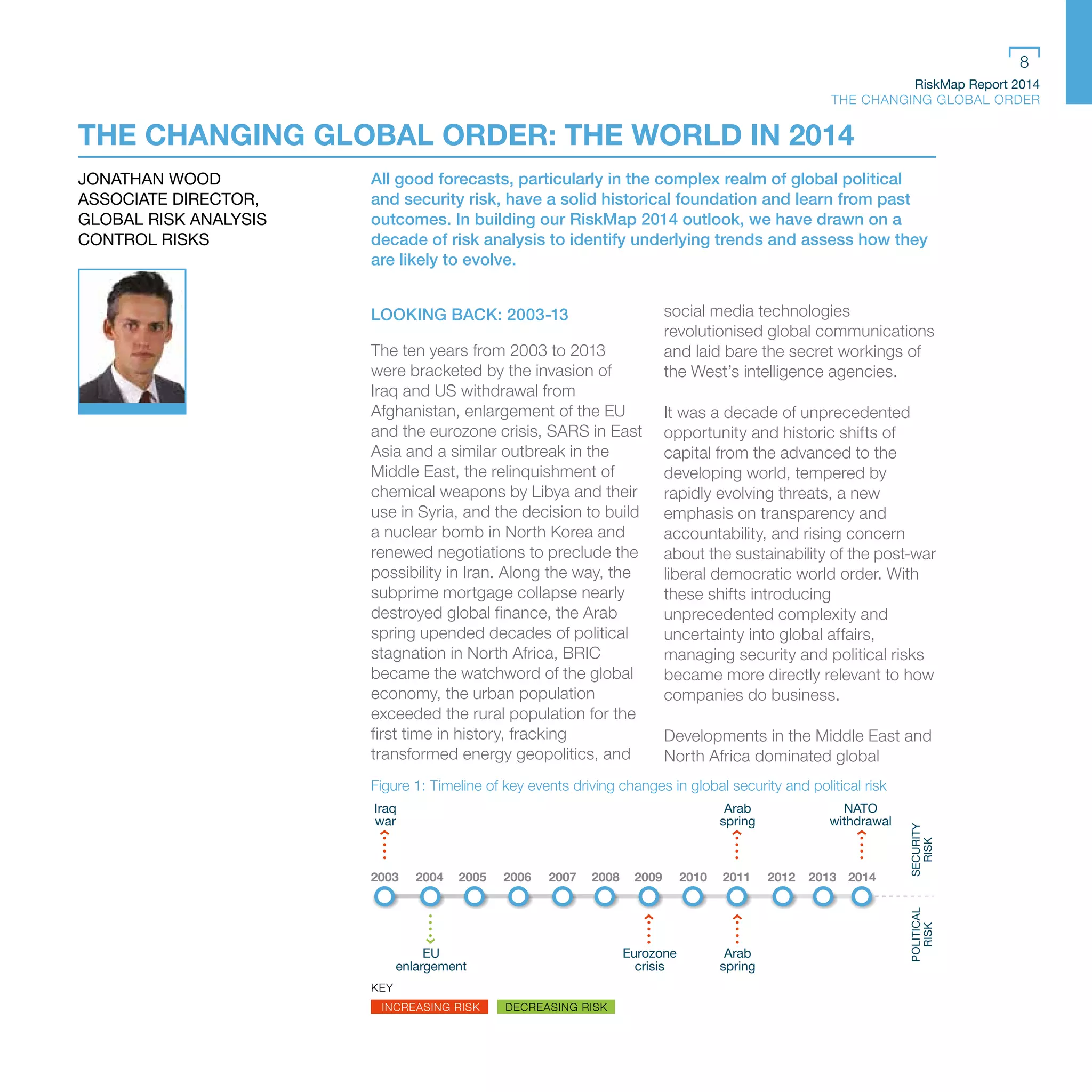

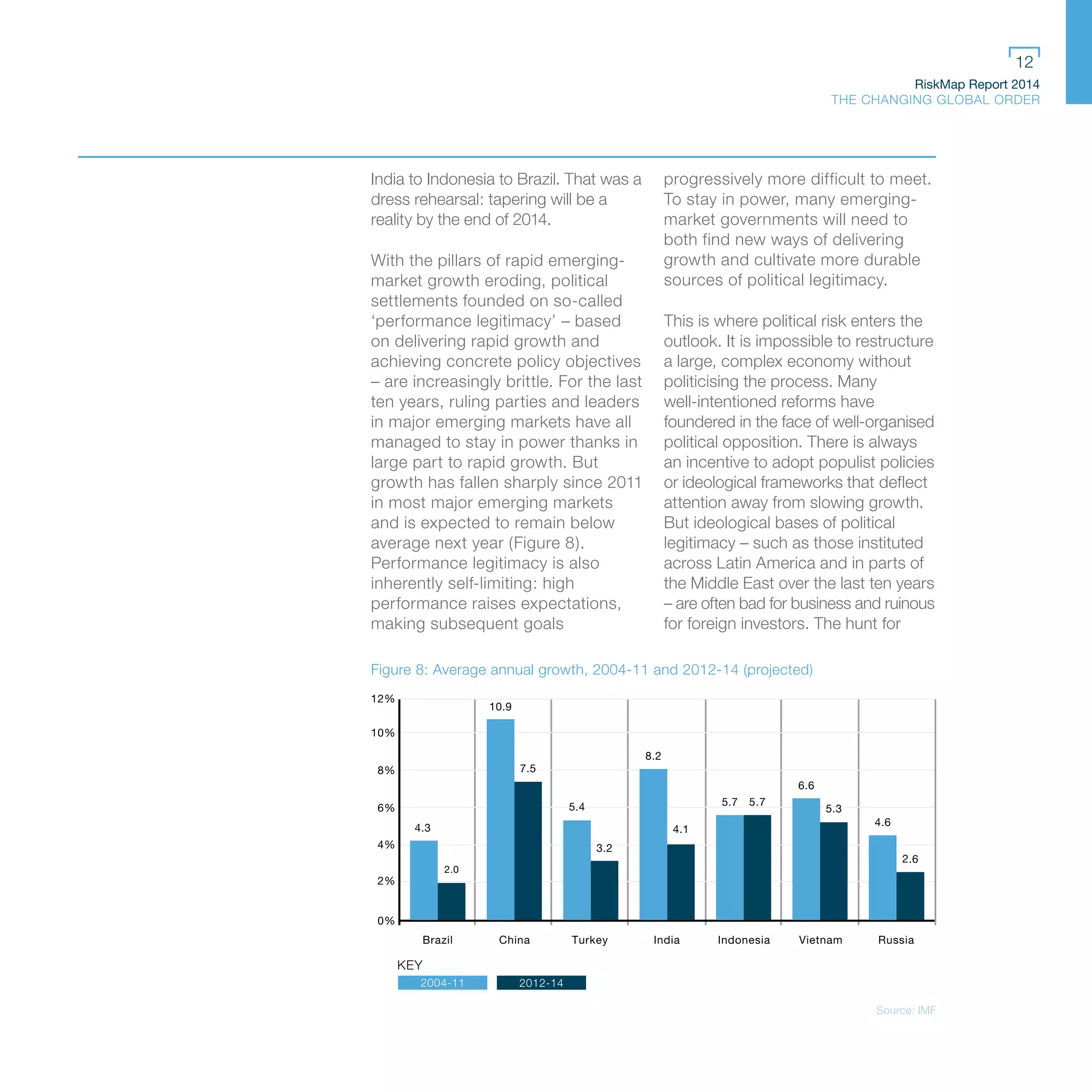

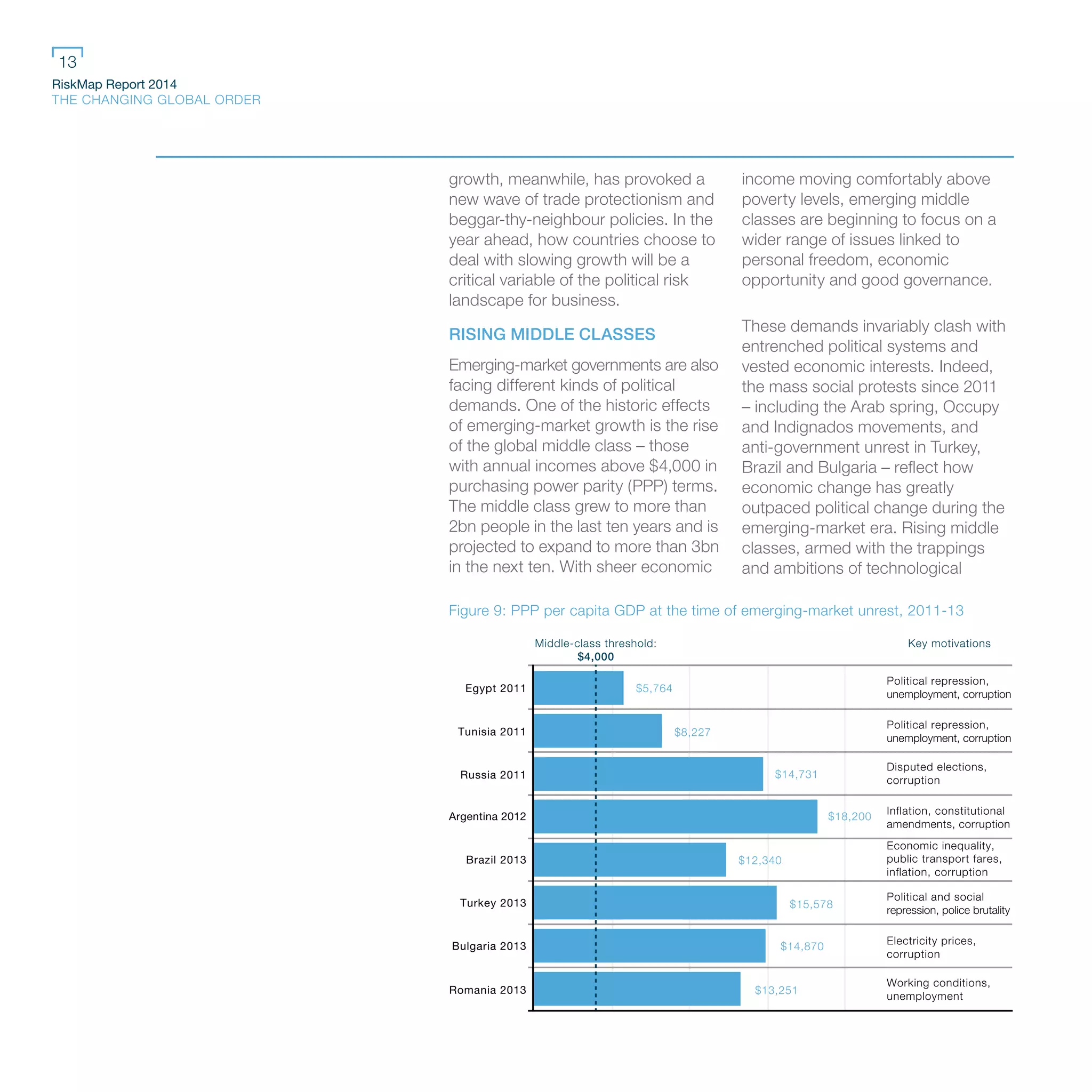

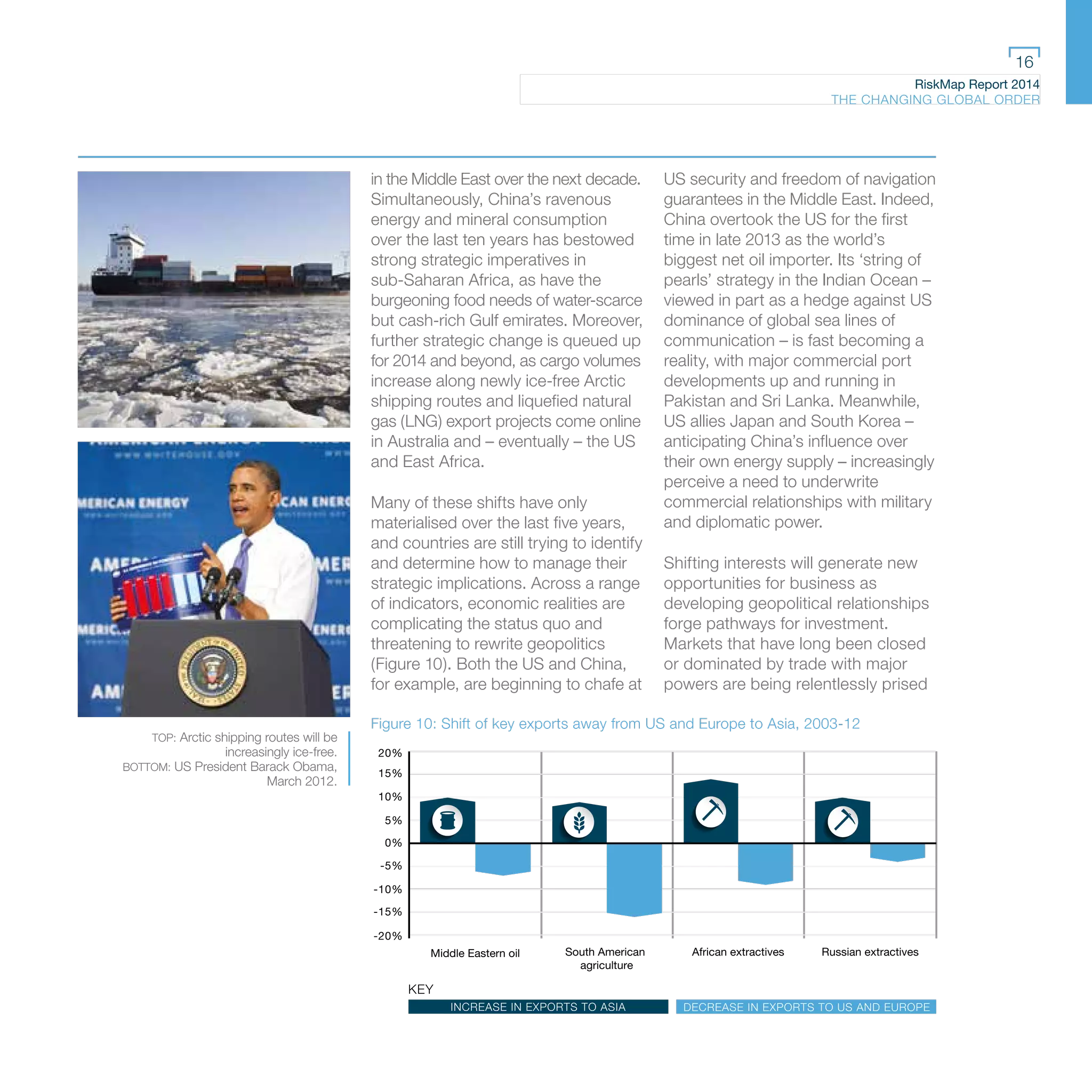

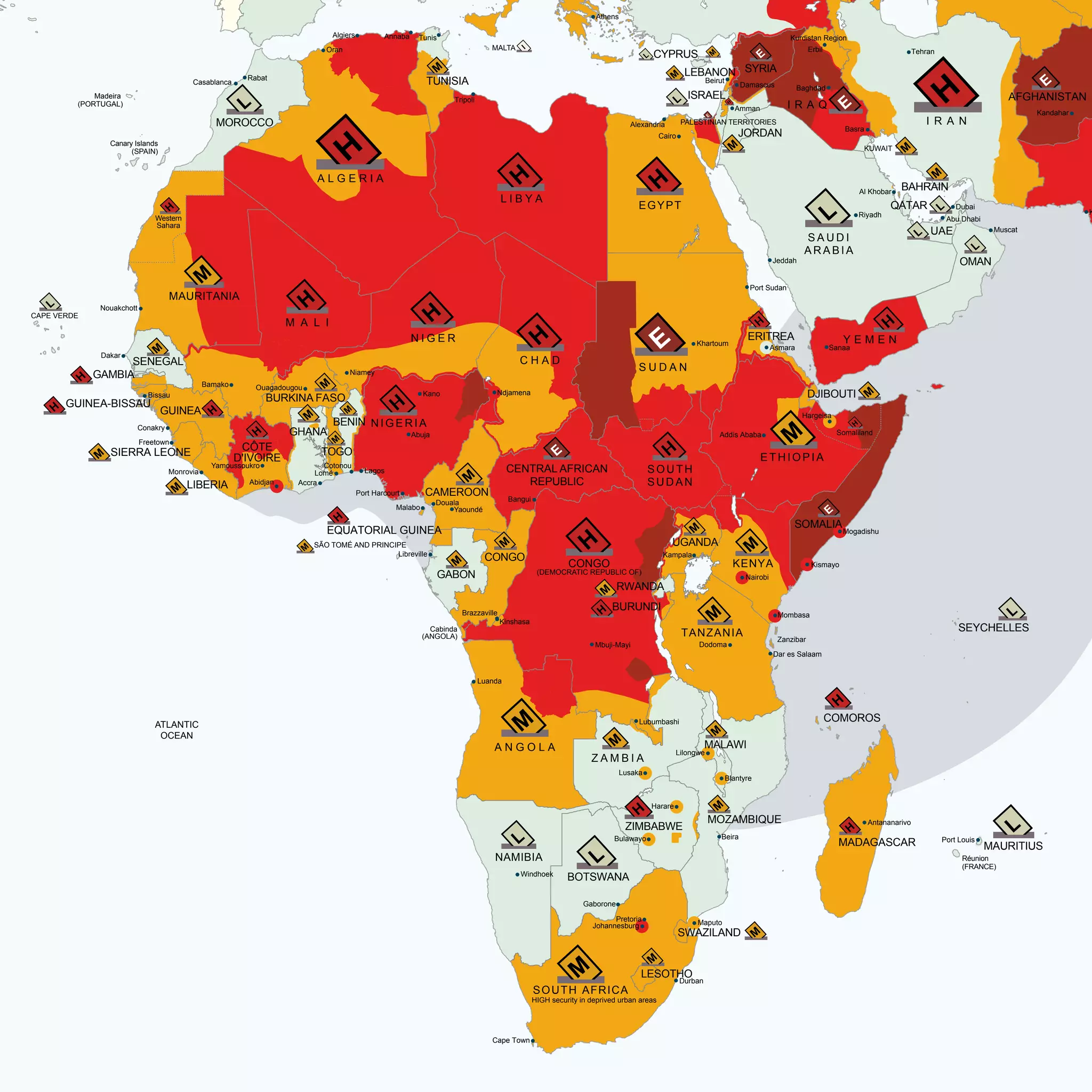

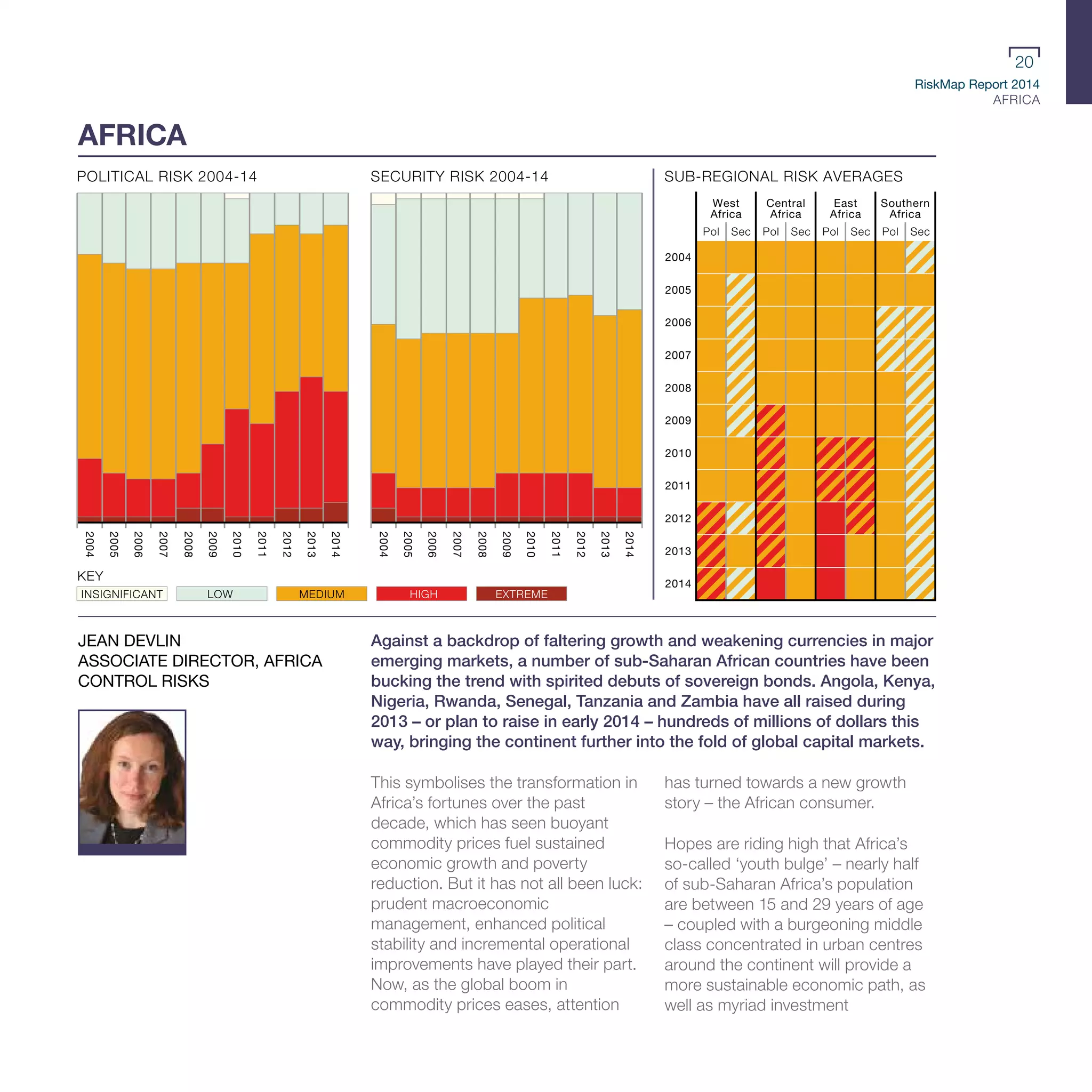

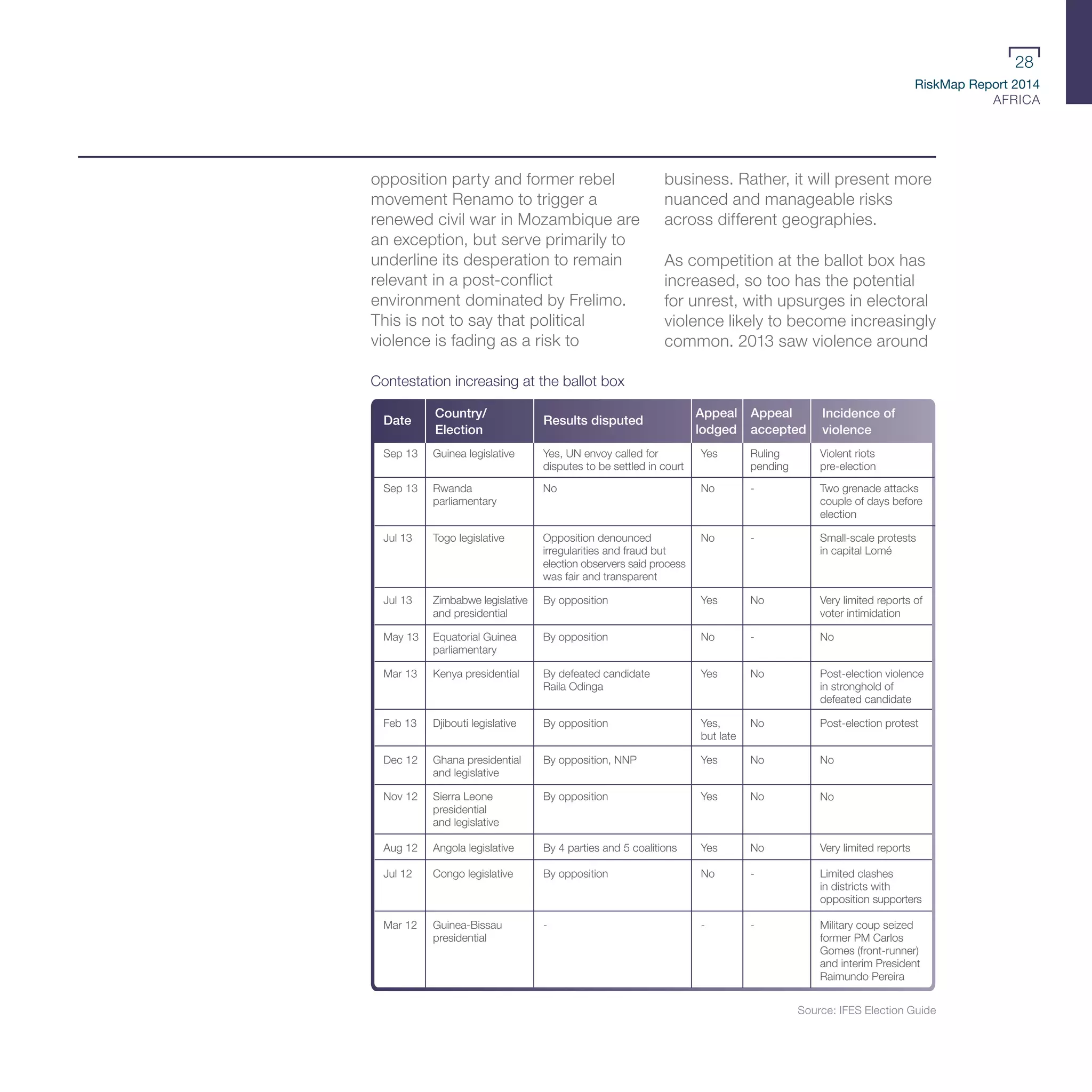

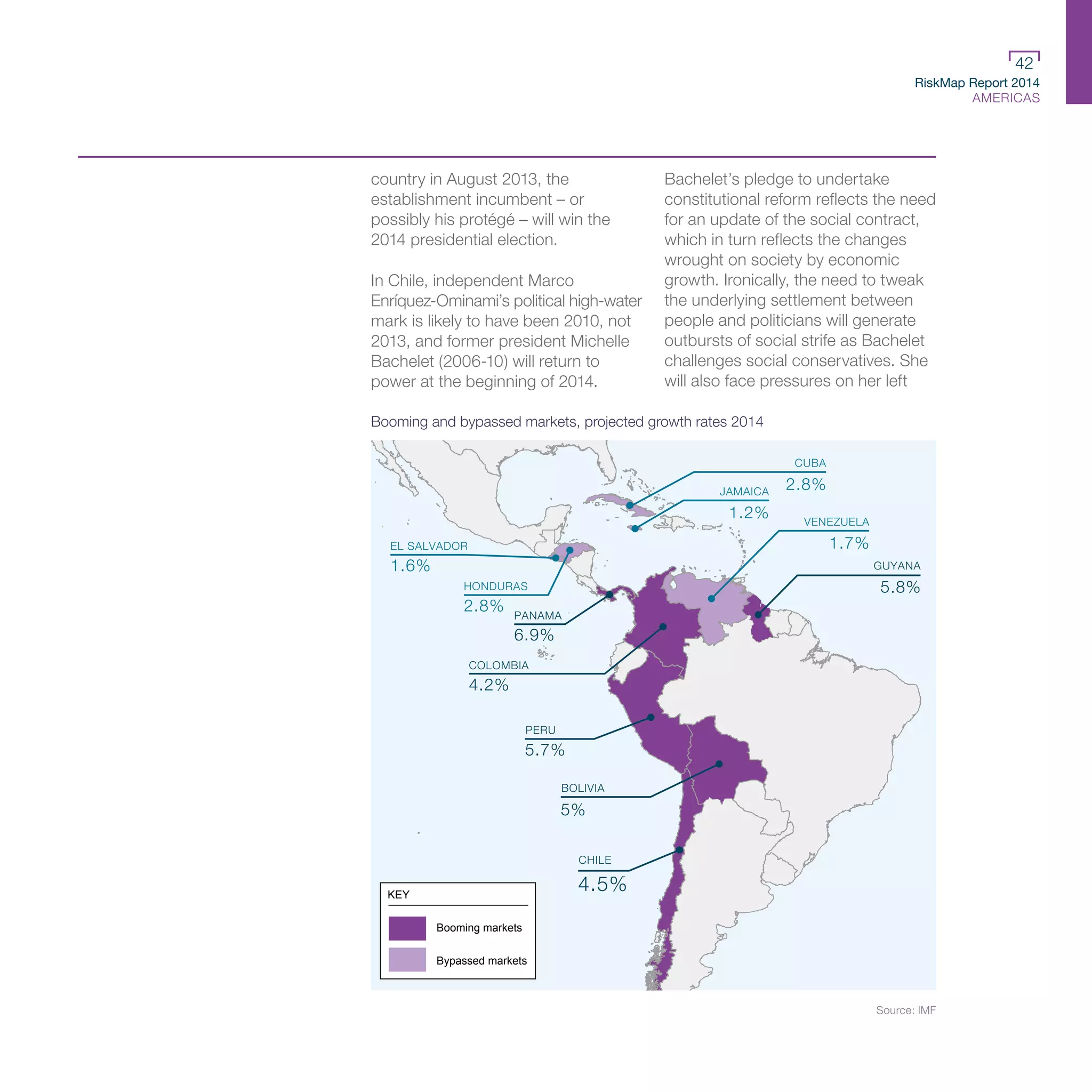

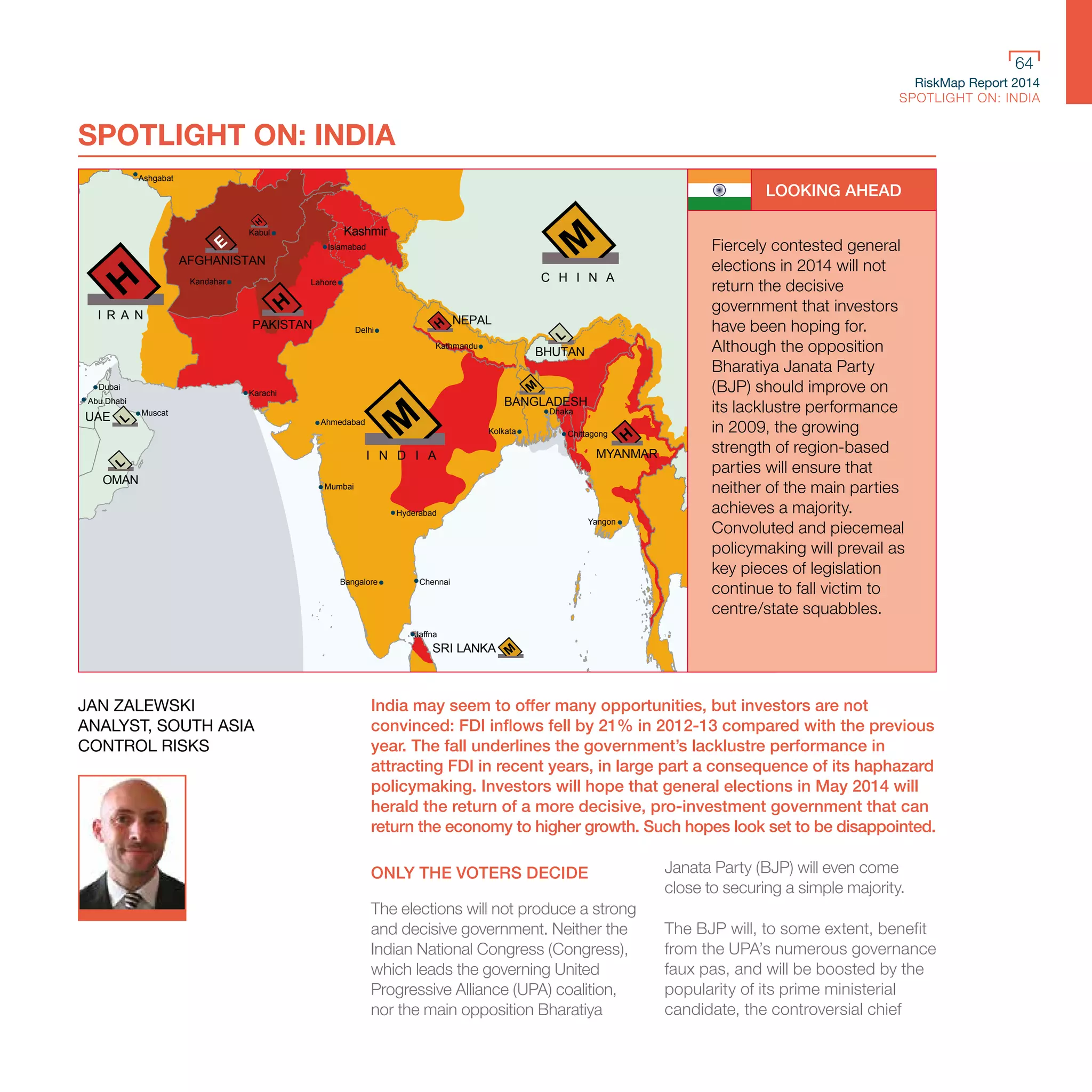

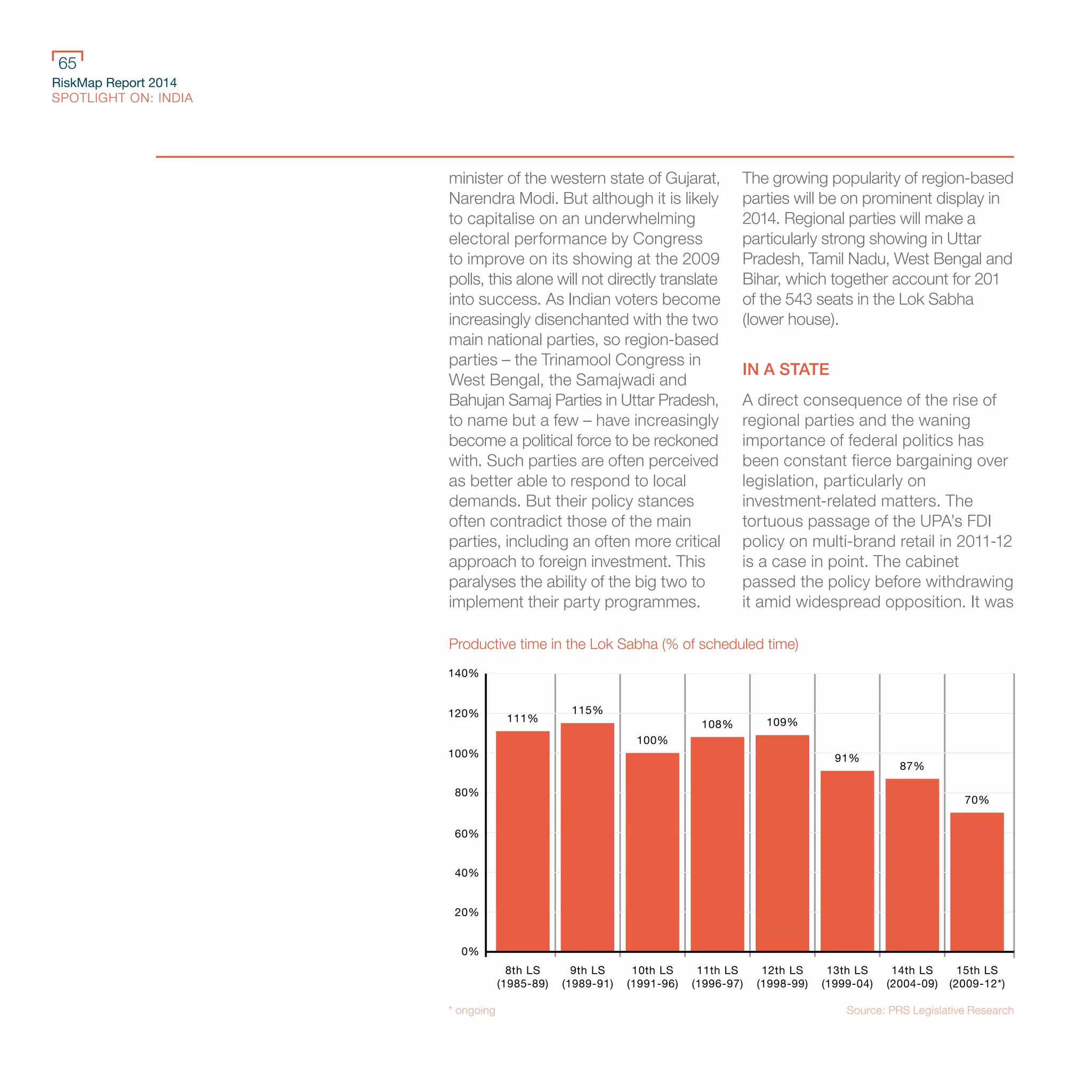

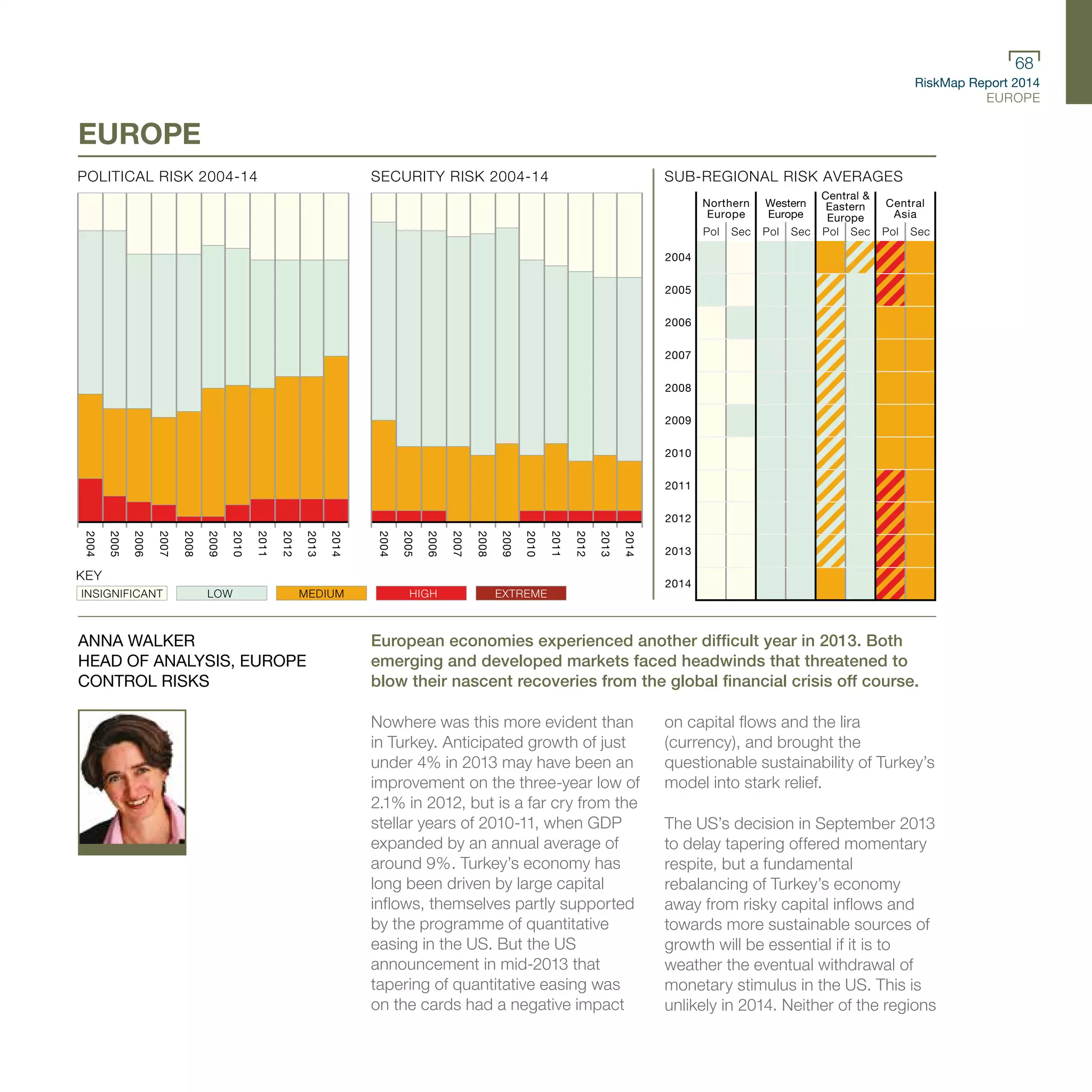

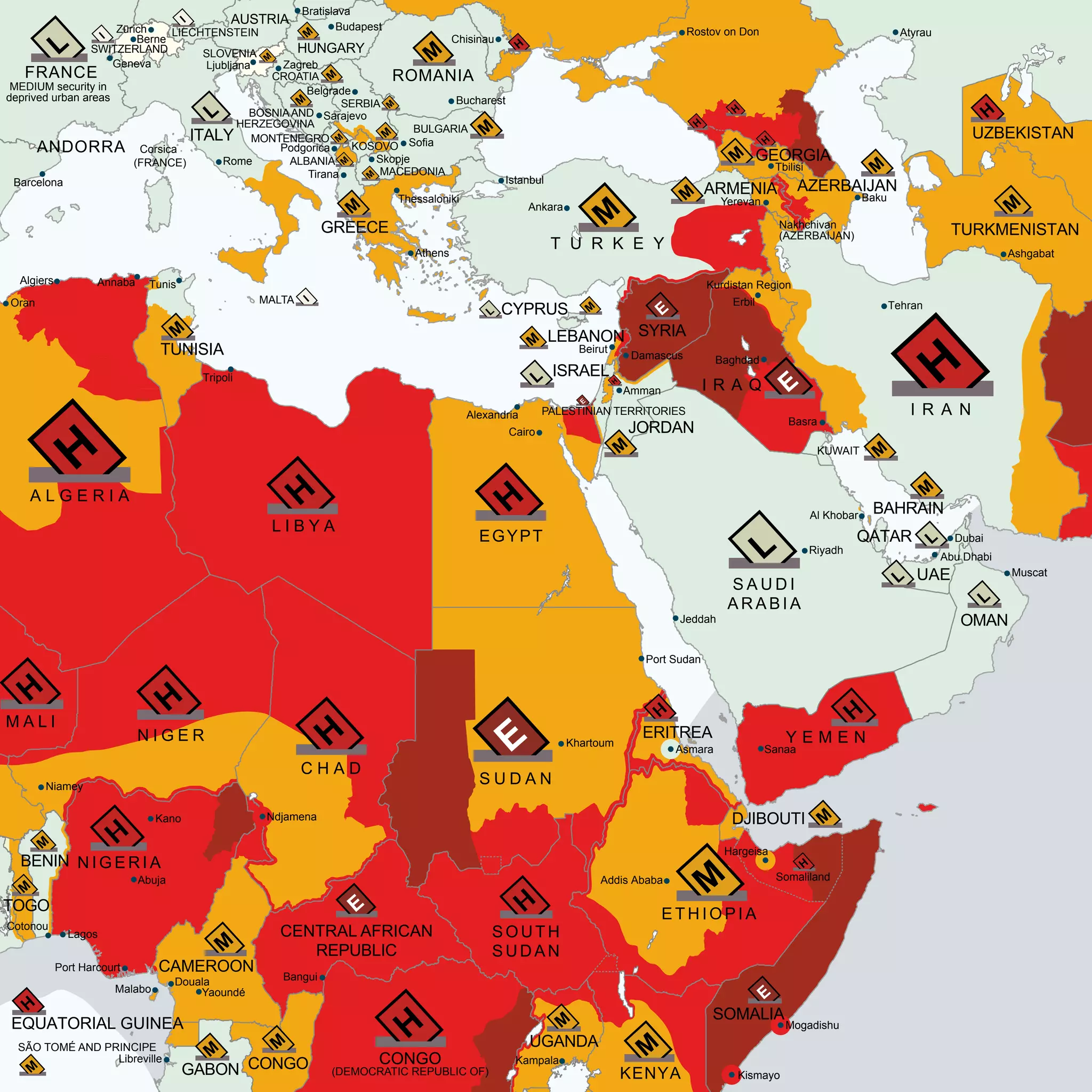

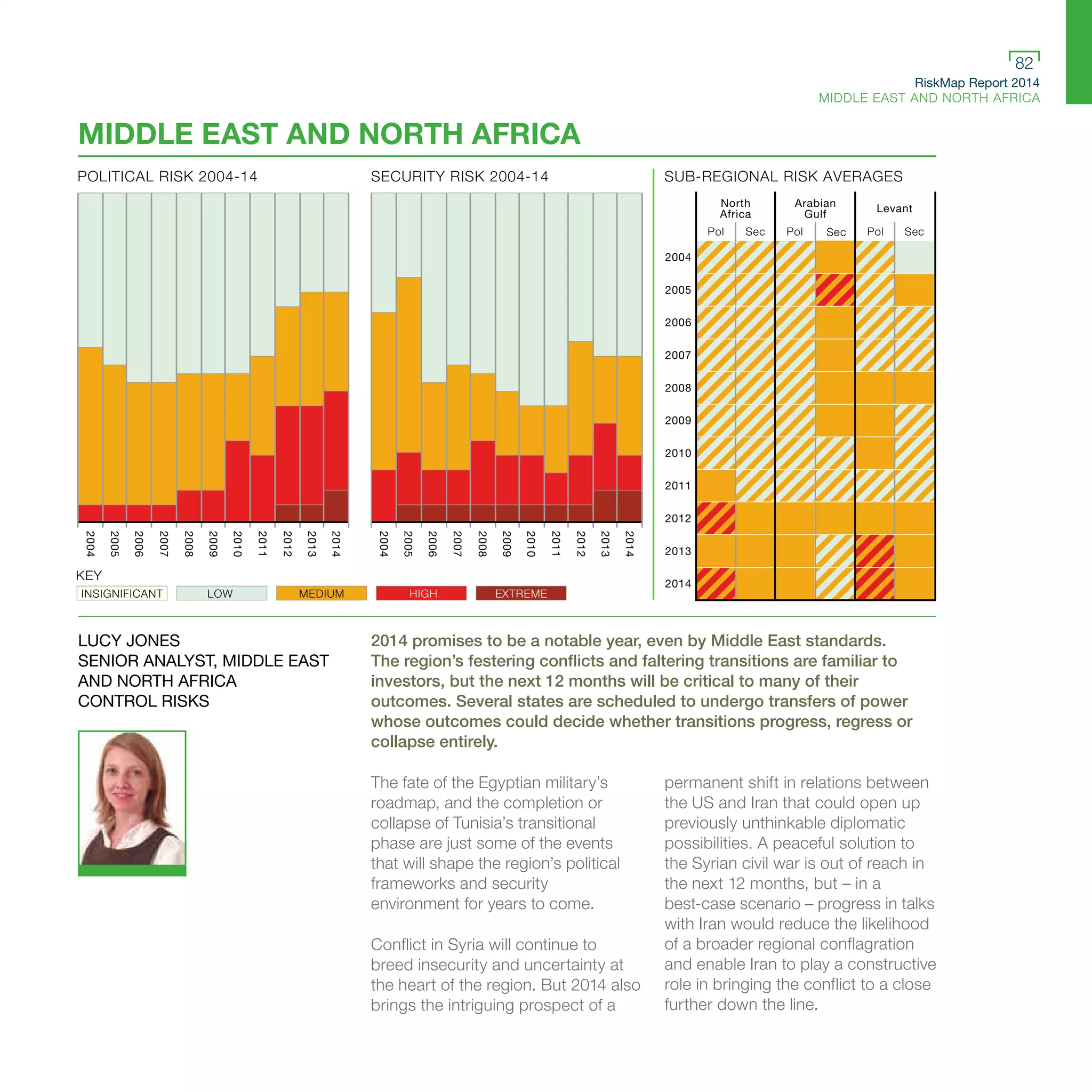

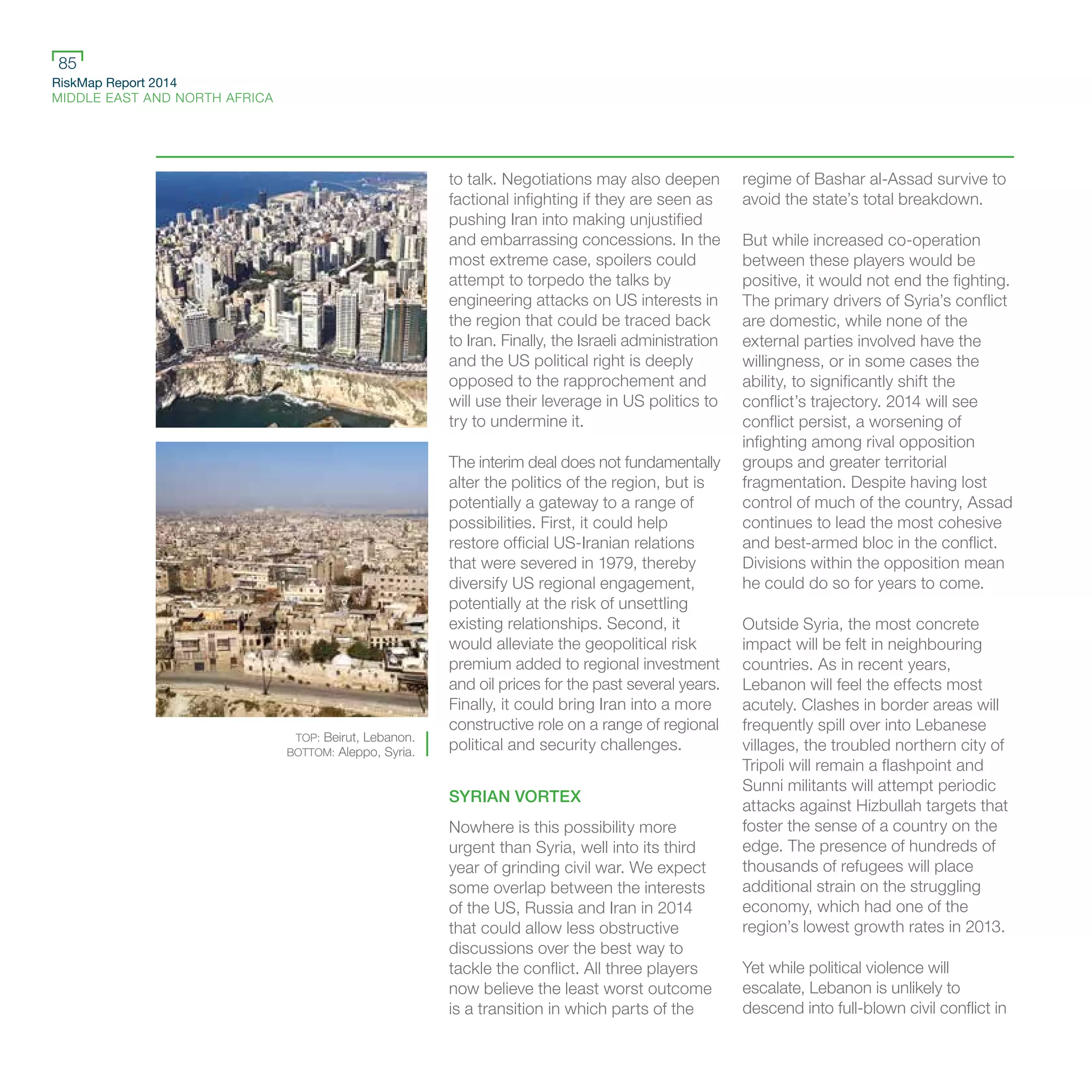

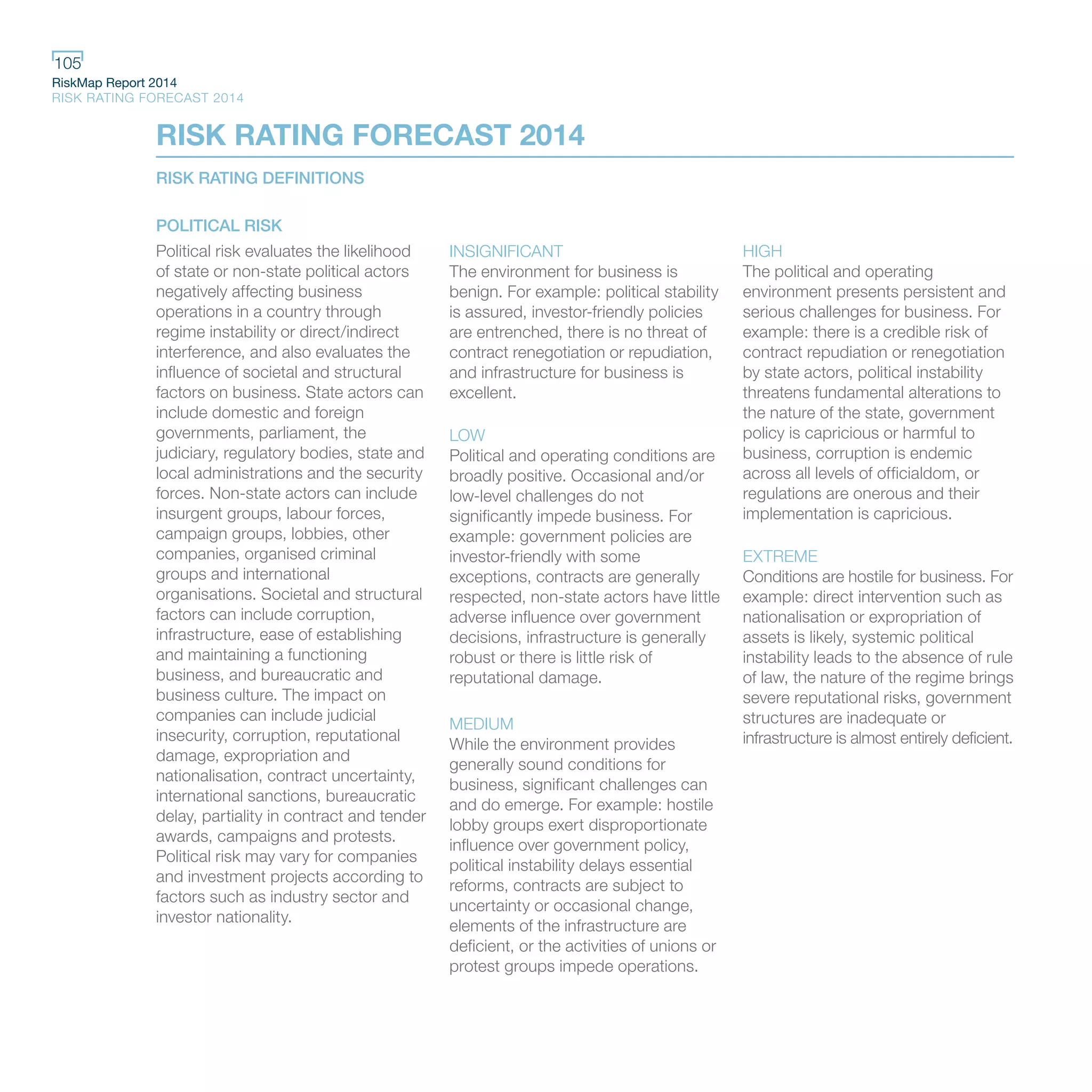

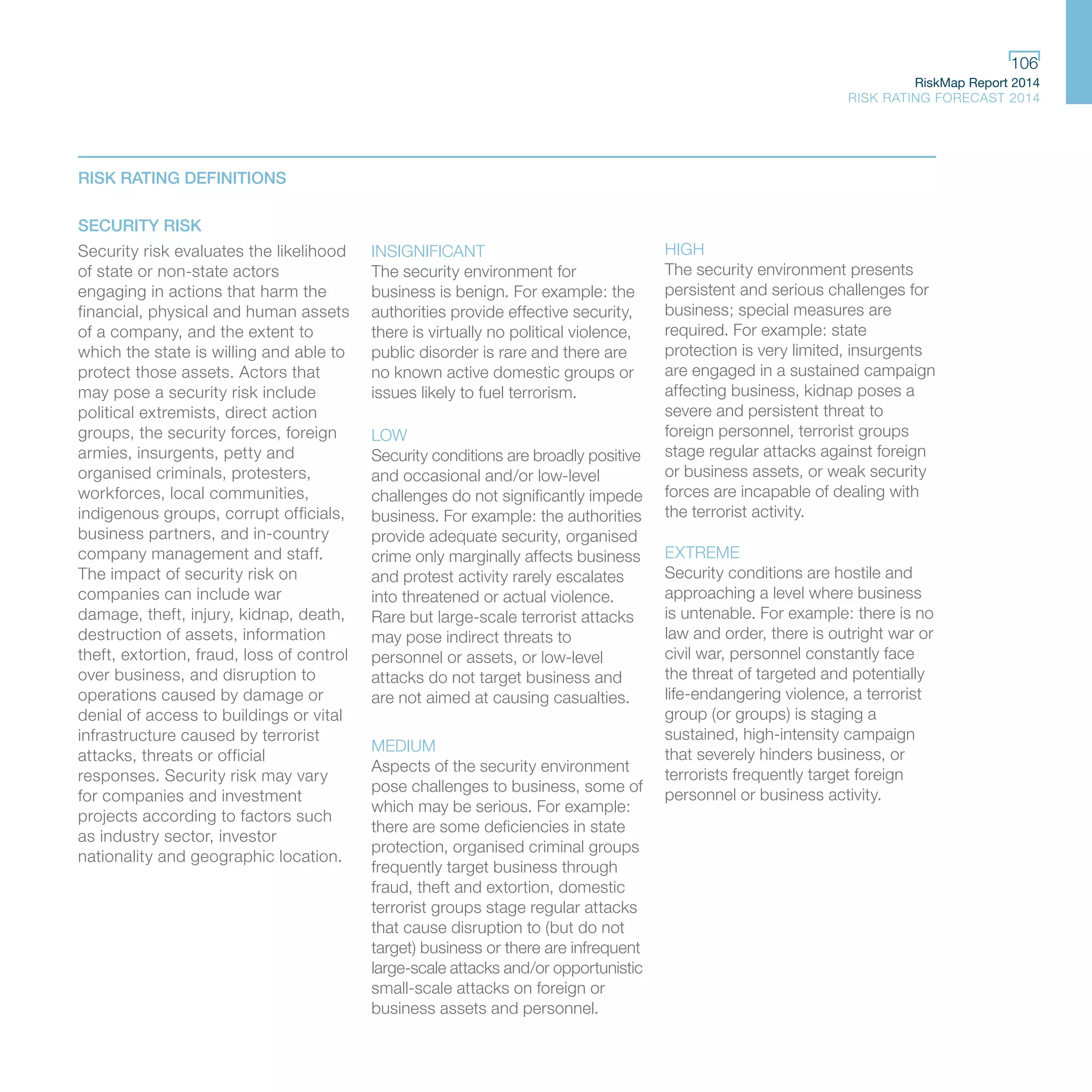

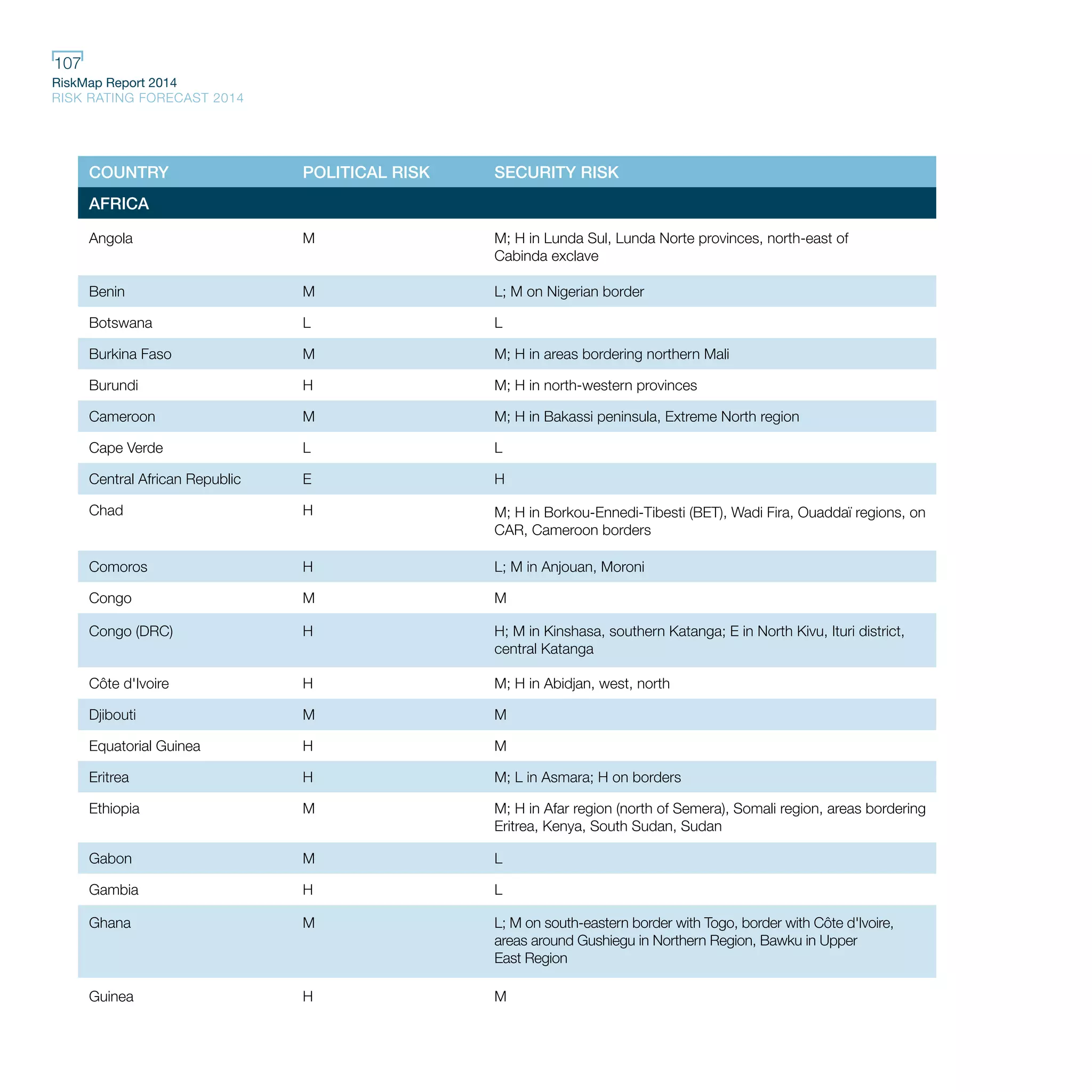

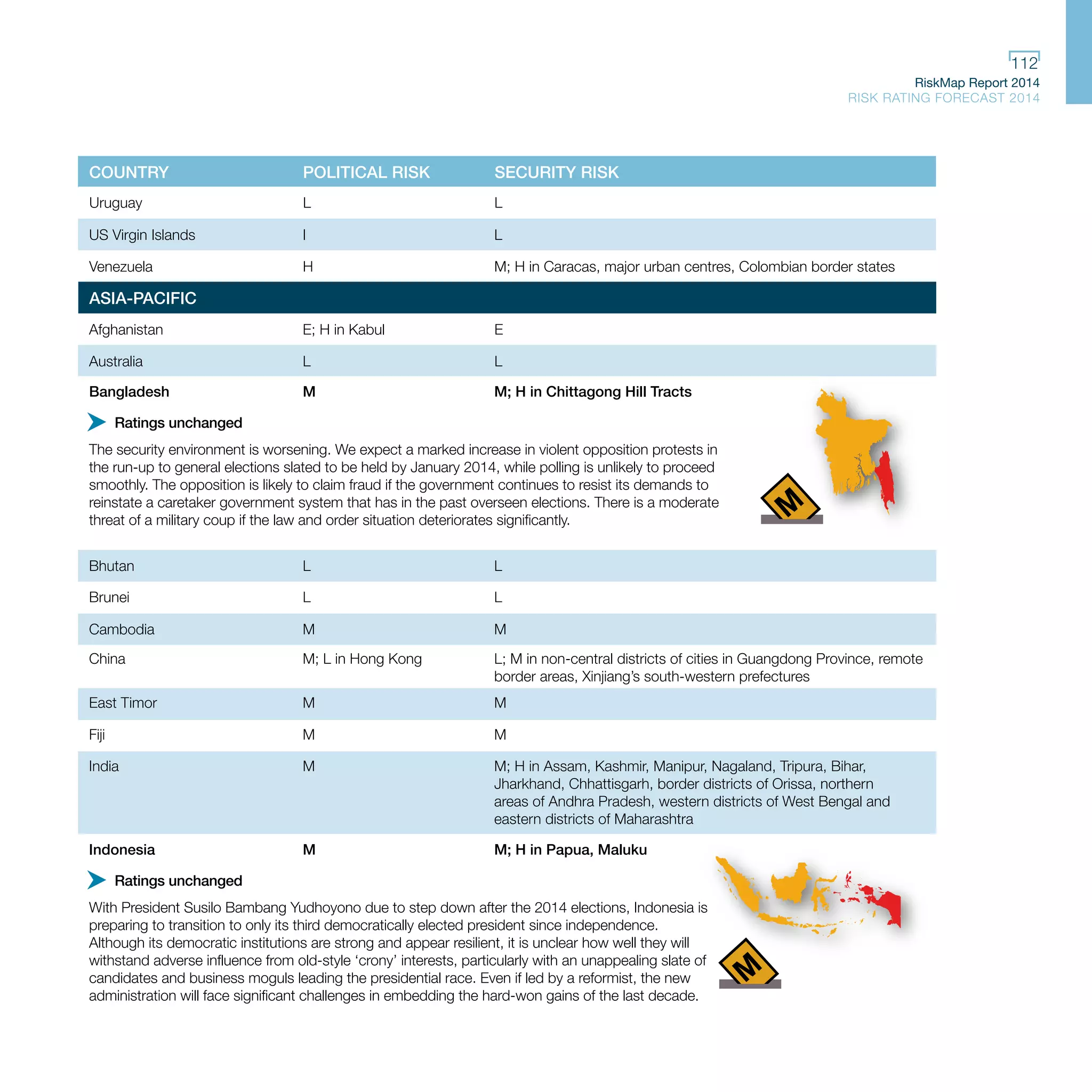

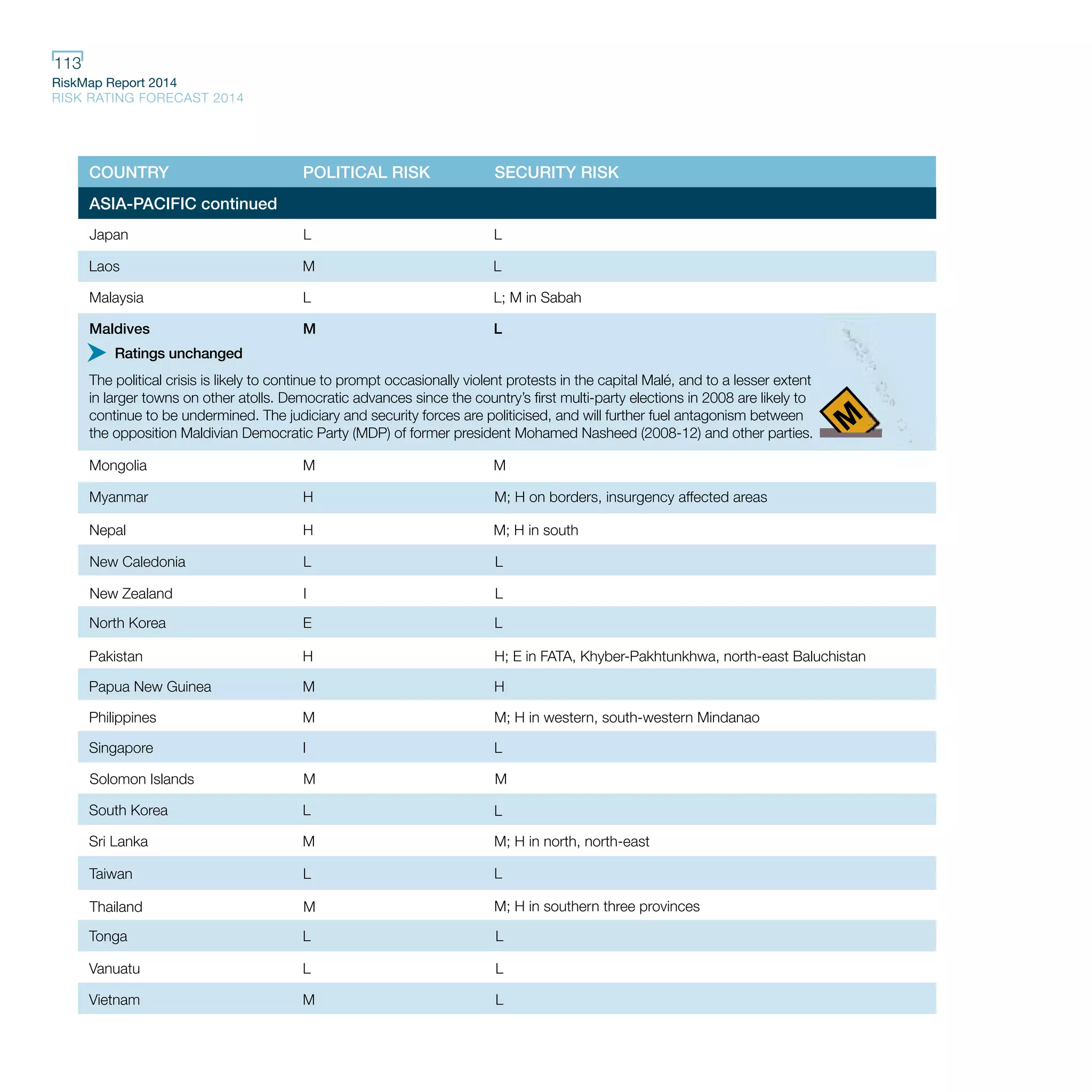

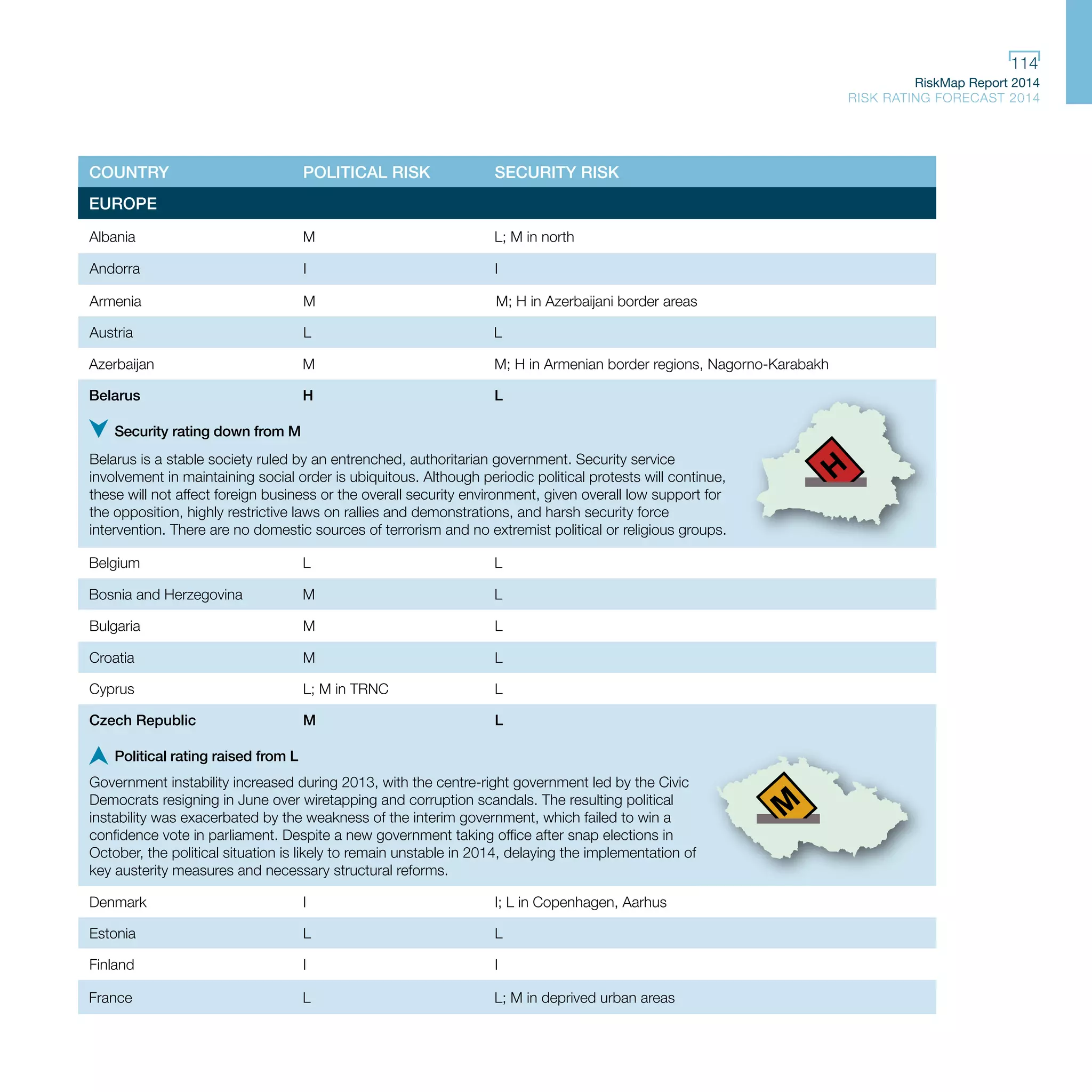

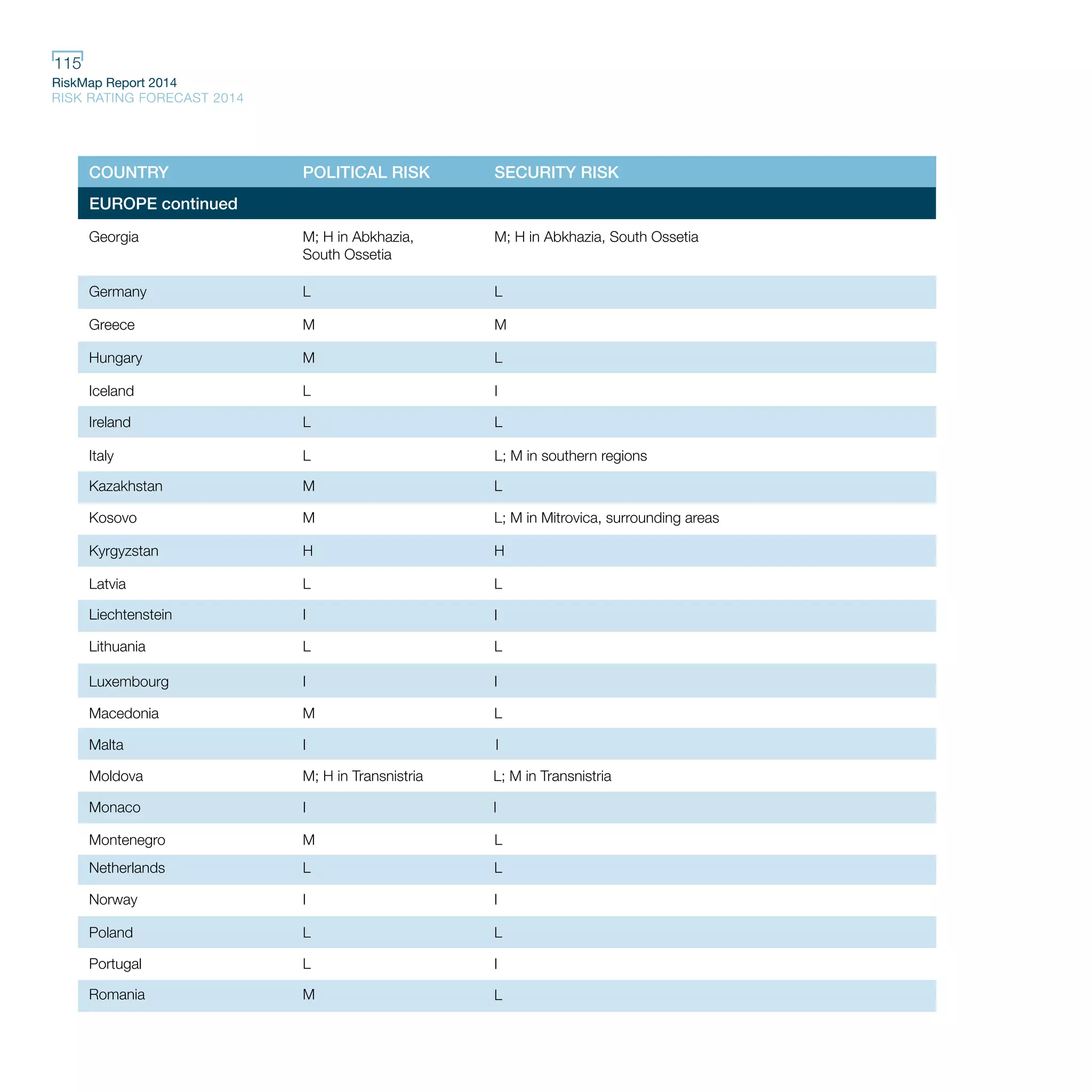

The document is a report by Control Risks titled "RiskMap Report 2014" that discusses major risks facing businesses in the coming year. It notes that as companies pursue increasingly complex global structures, they face new vulnerabilities from local issues. Local political and security risks can now rapidly spread and impact companies globally. Several major risks are highlighted for 2014, including slowing growth in emerging markets, ongoing conflicts in the Middle East, and election-related instability in some large economies like India and Brazil. The report argues that local political trends will be difficult for foreign companies to read as economic power shifts in many countries.