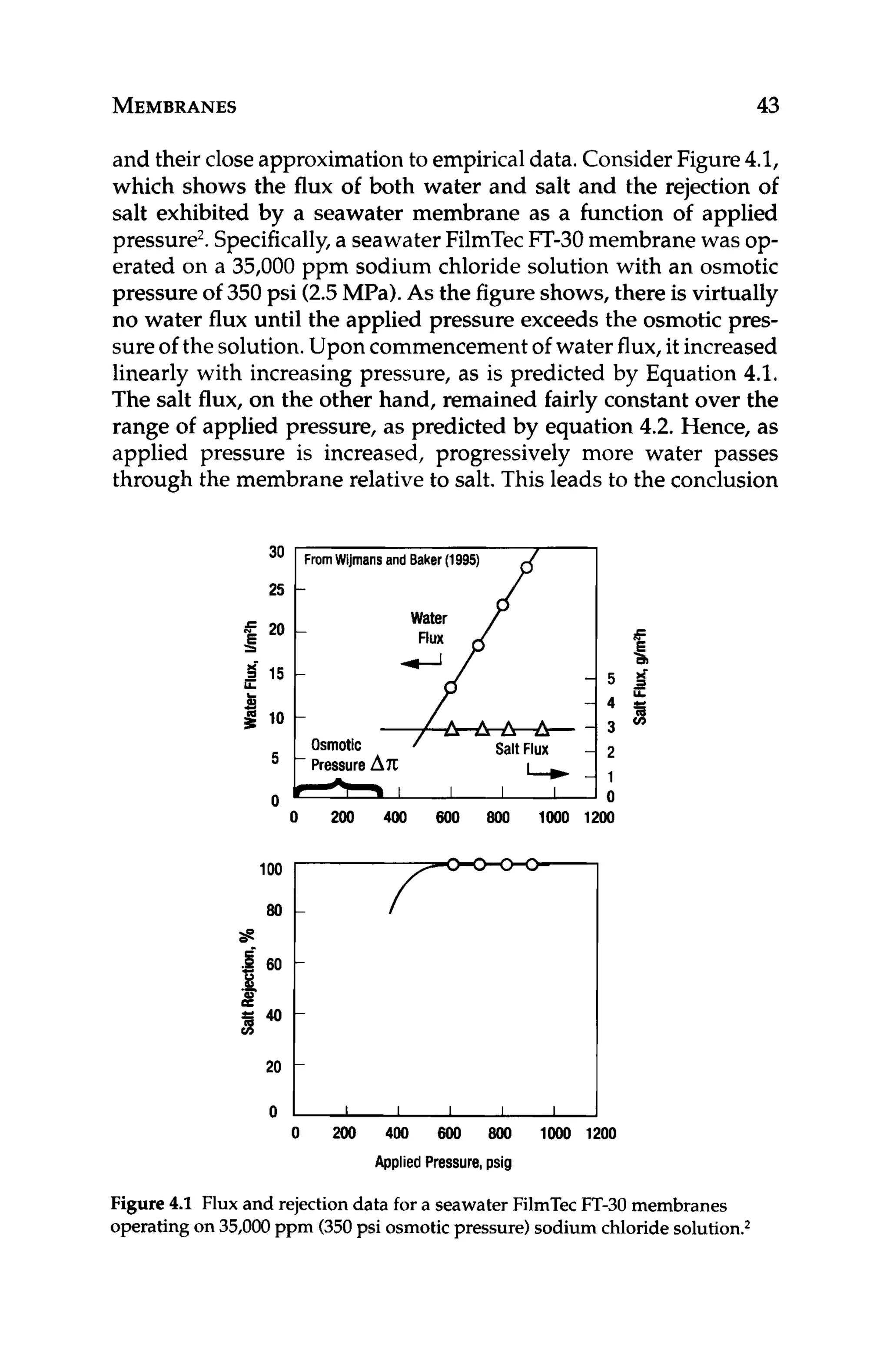

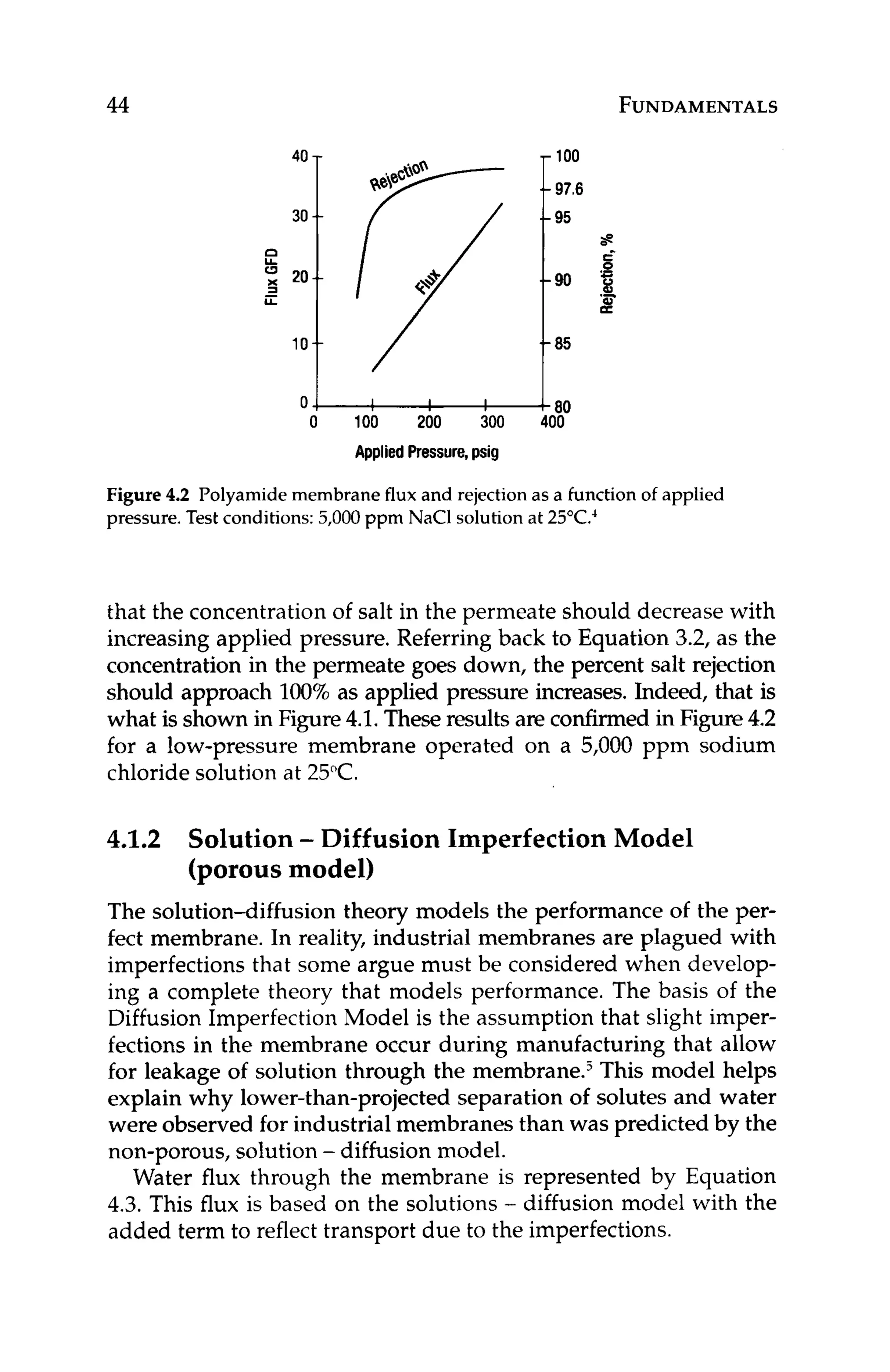

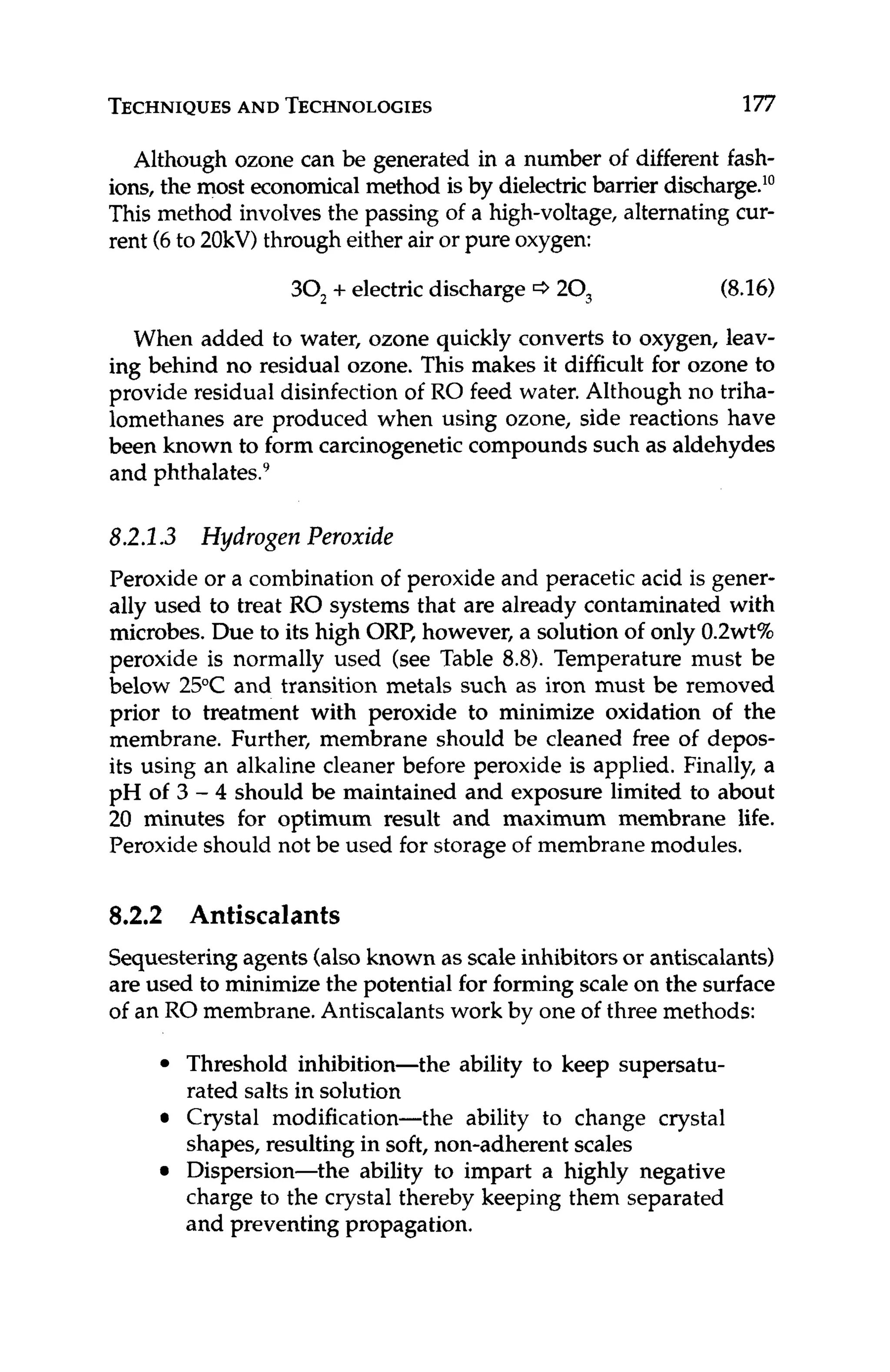

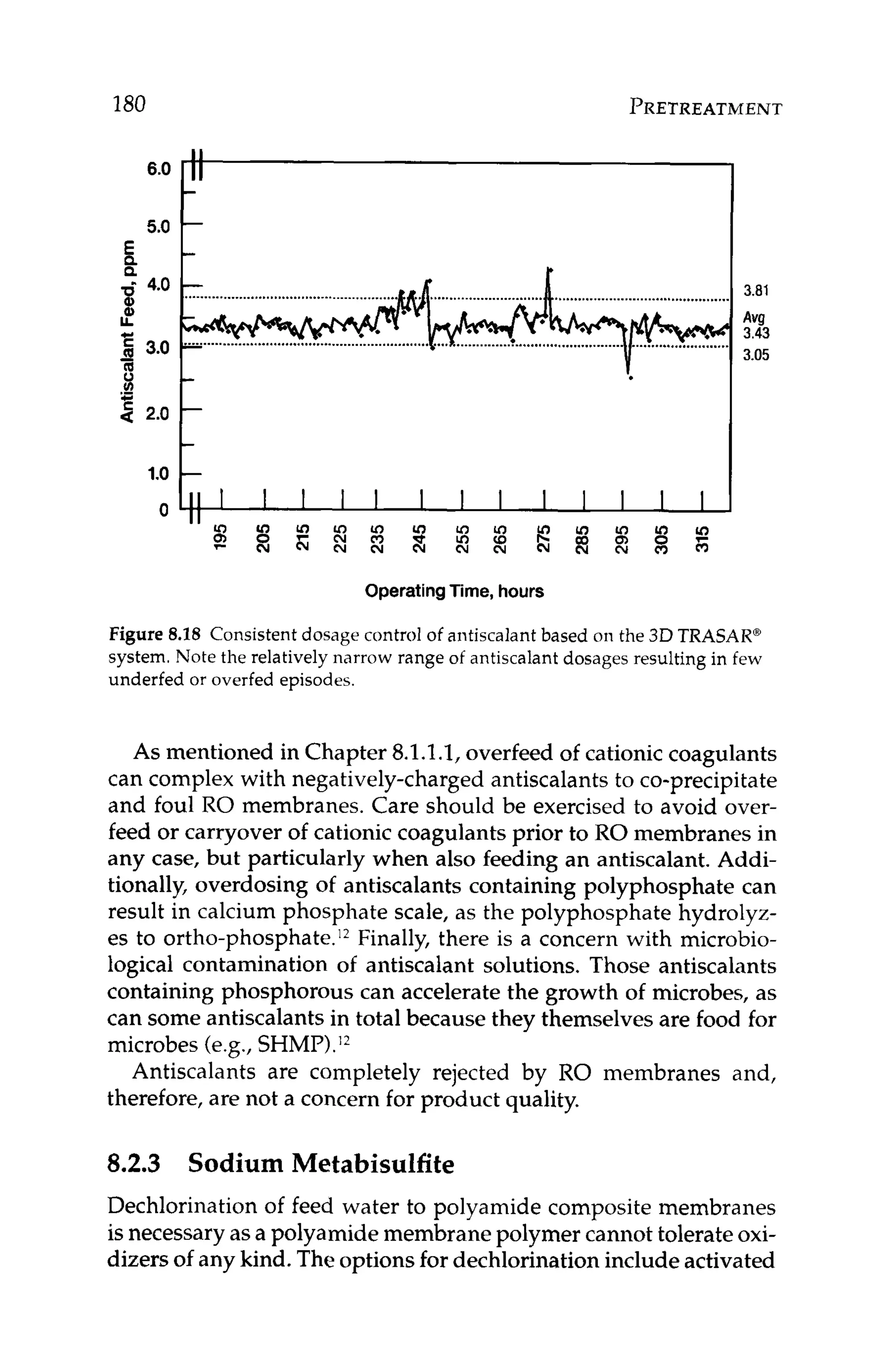

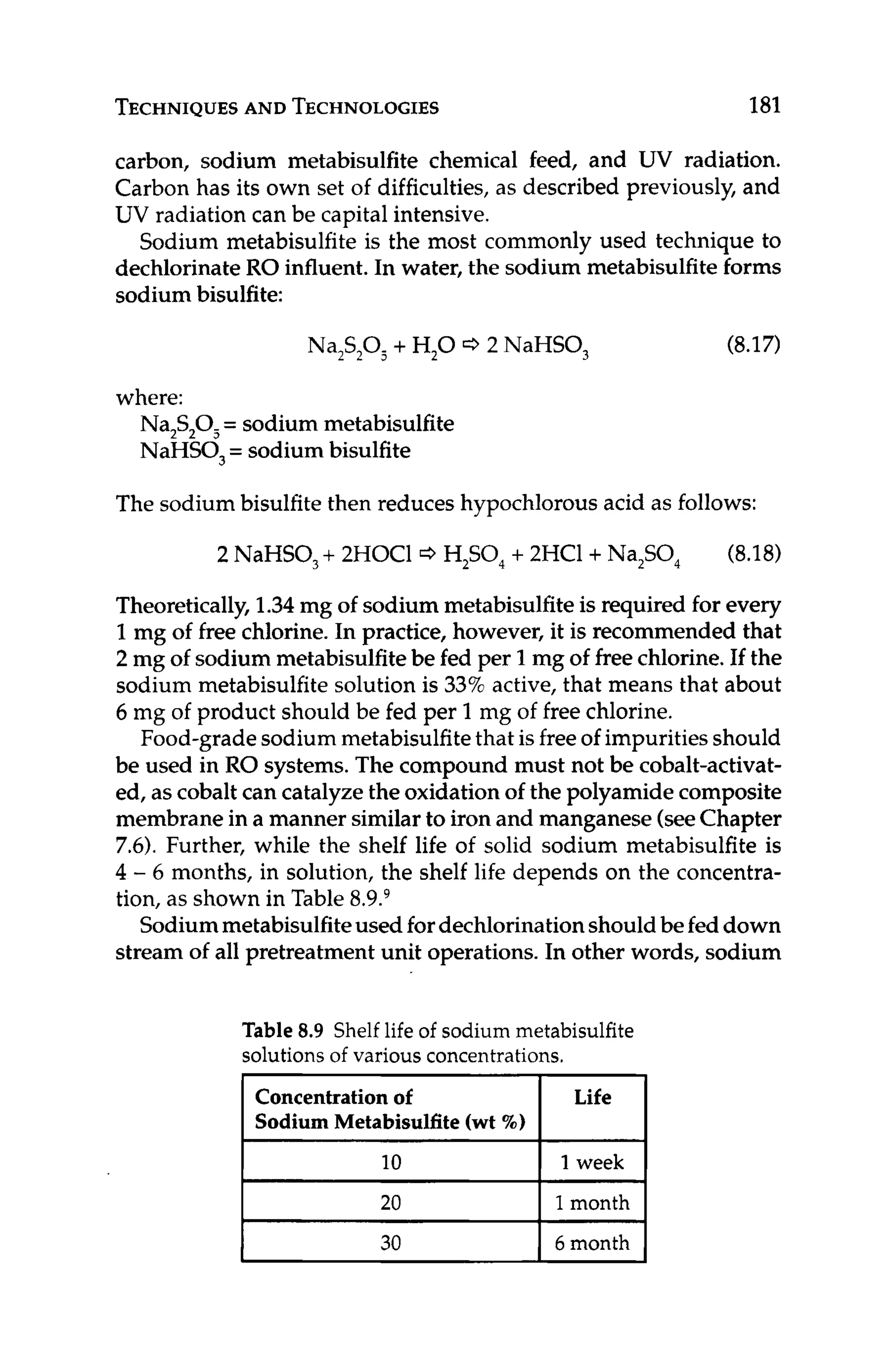

This document provides an overview of reverse osmosis (RO) membrane technology and system design. It discusses the history and development of RO, fundamental principles, membrane materials and configurations, pretreatment techniques, and system design, operation, and troubleshooting. The document is intended to serve as a reference for engineers working with RO systems.

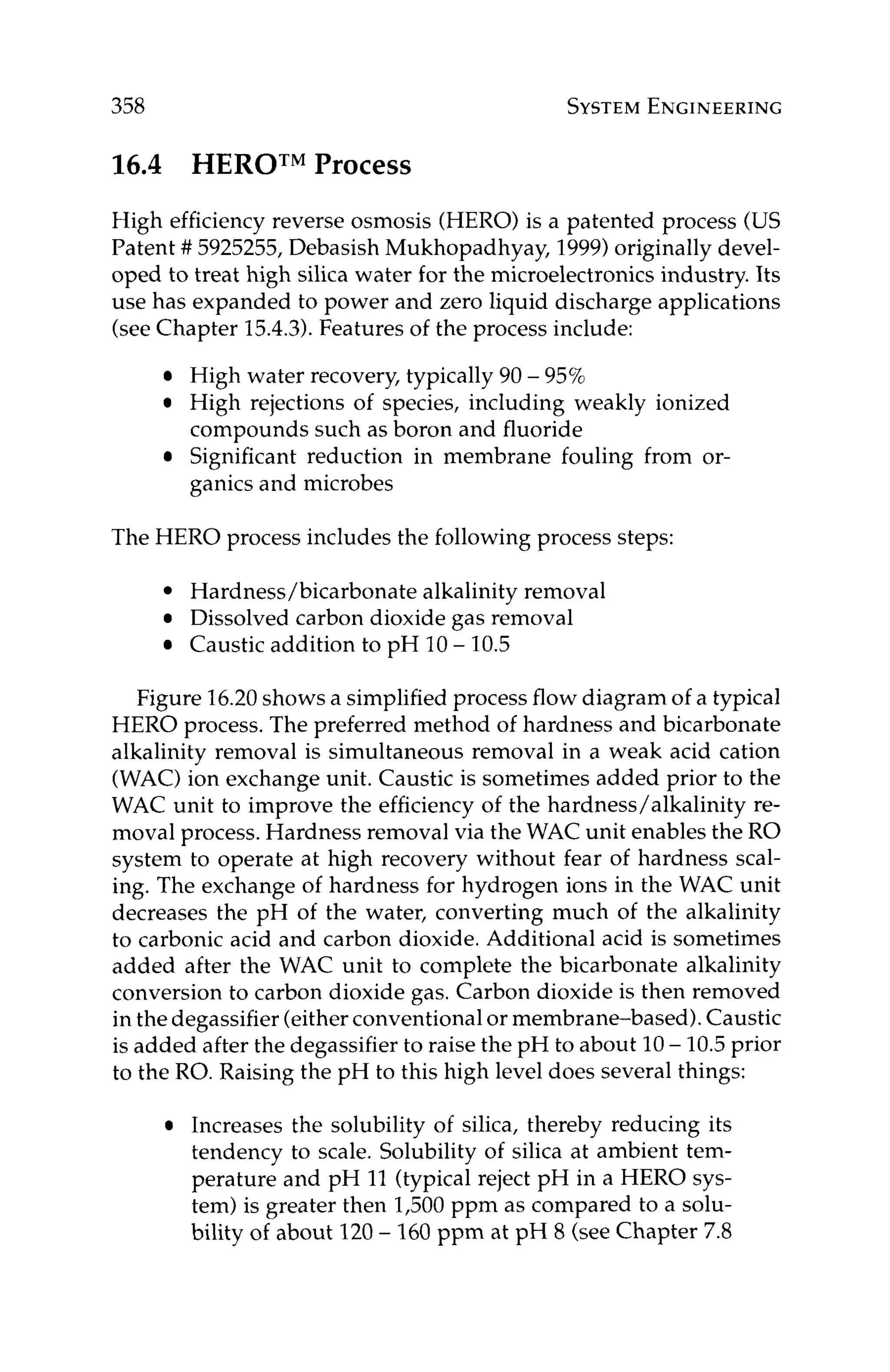

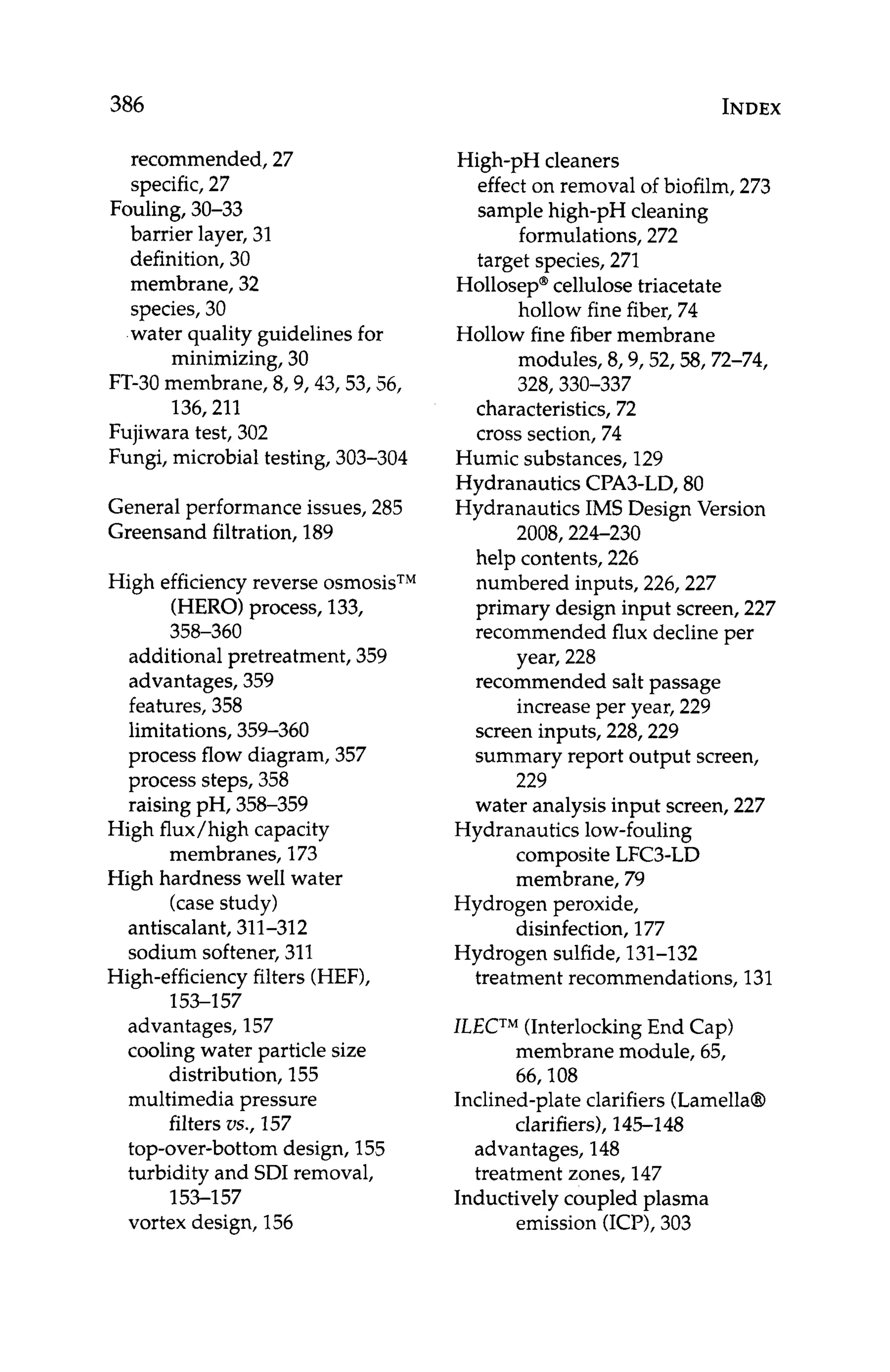

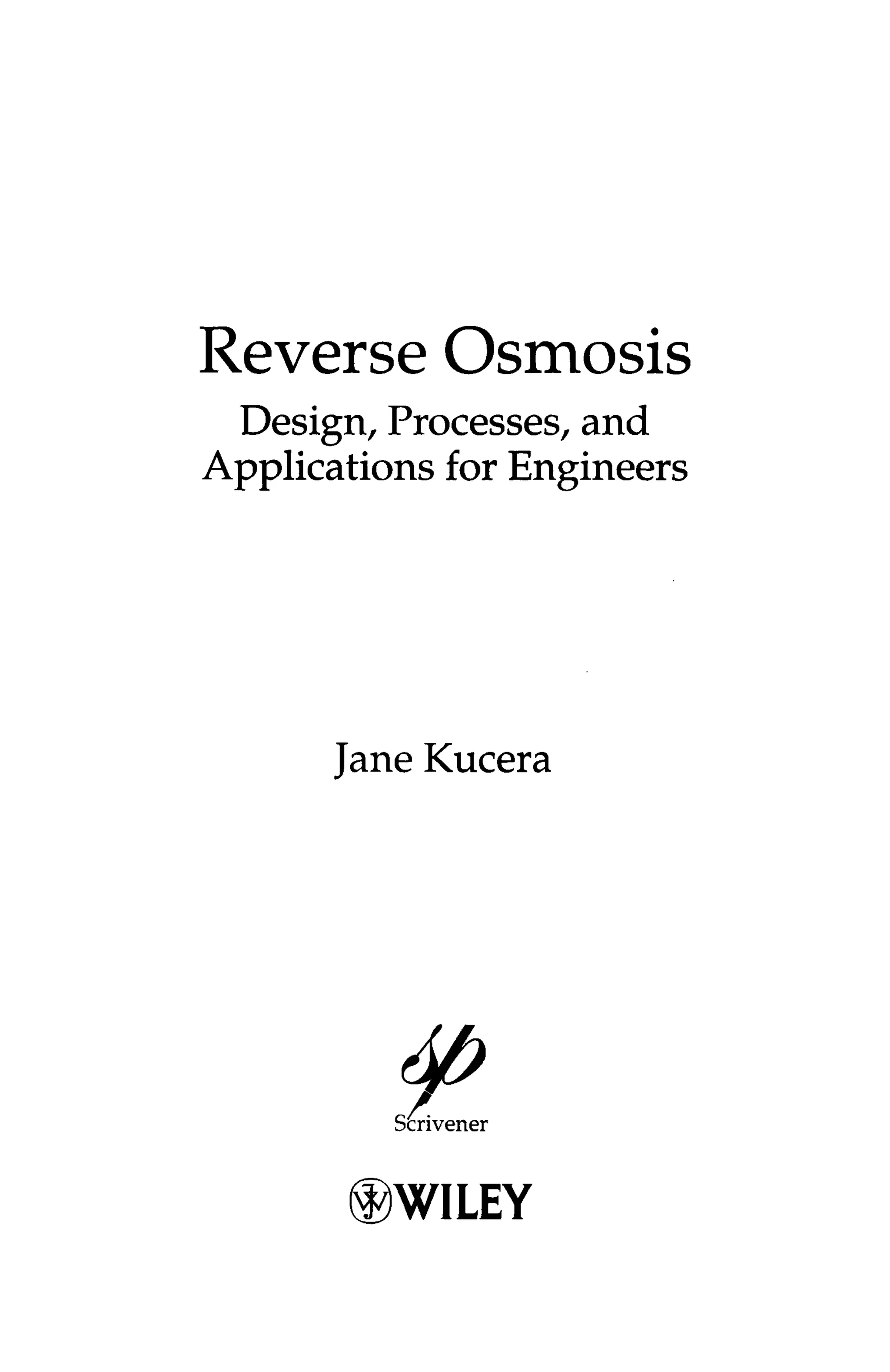

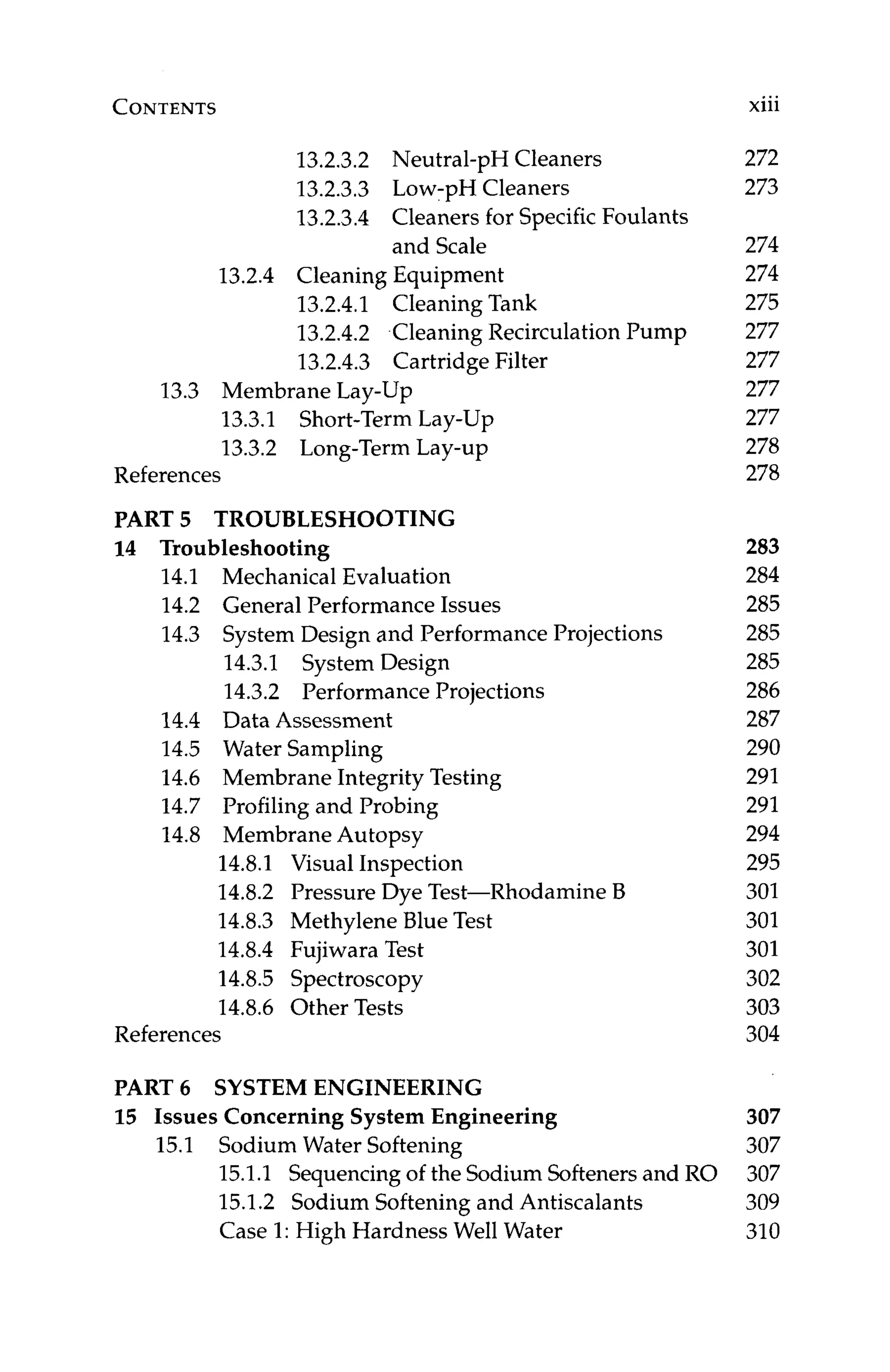

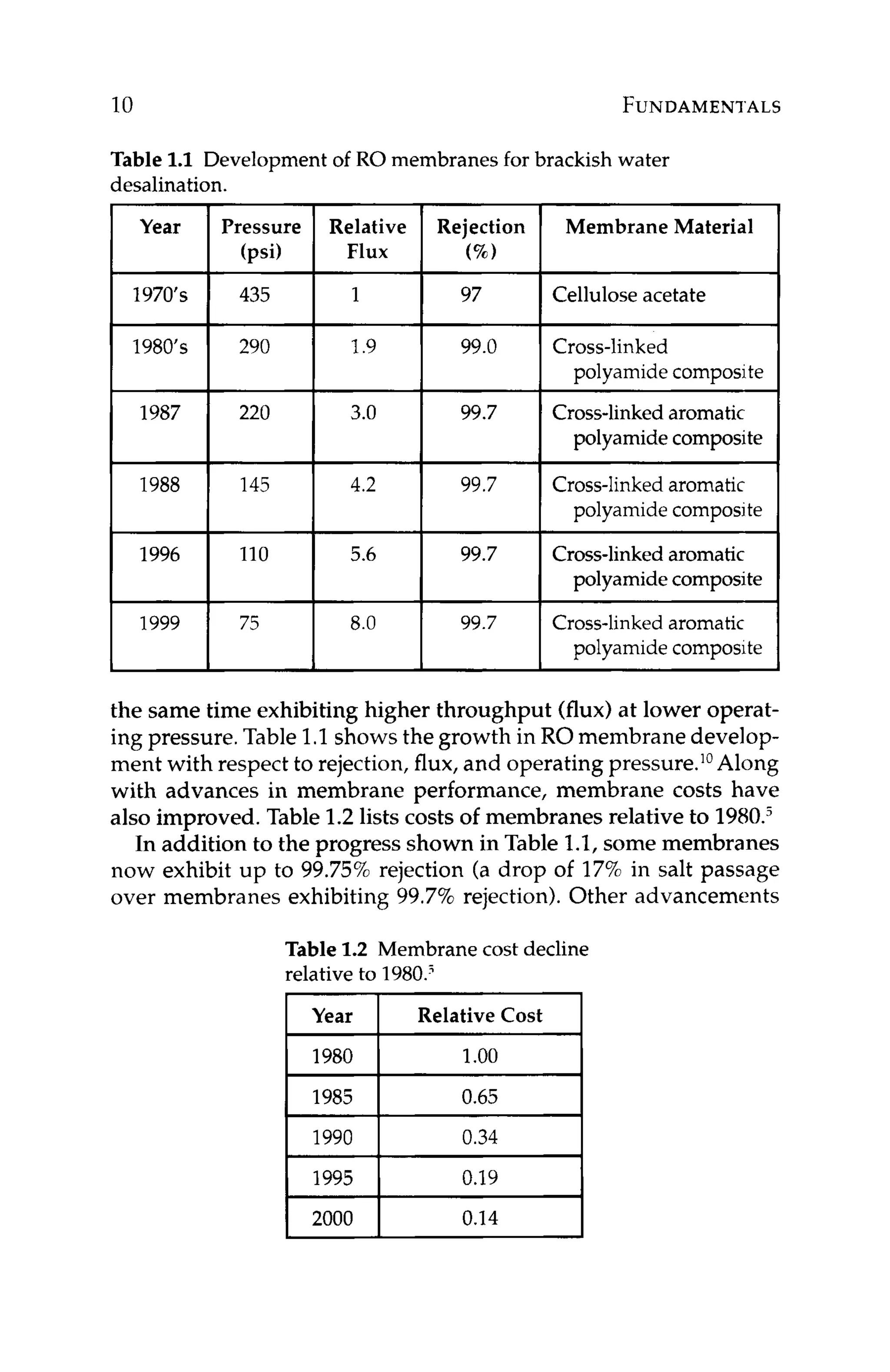

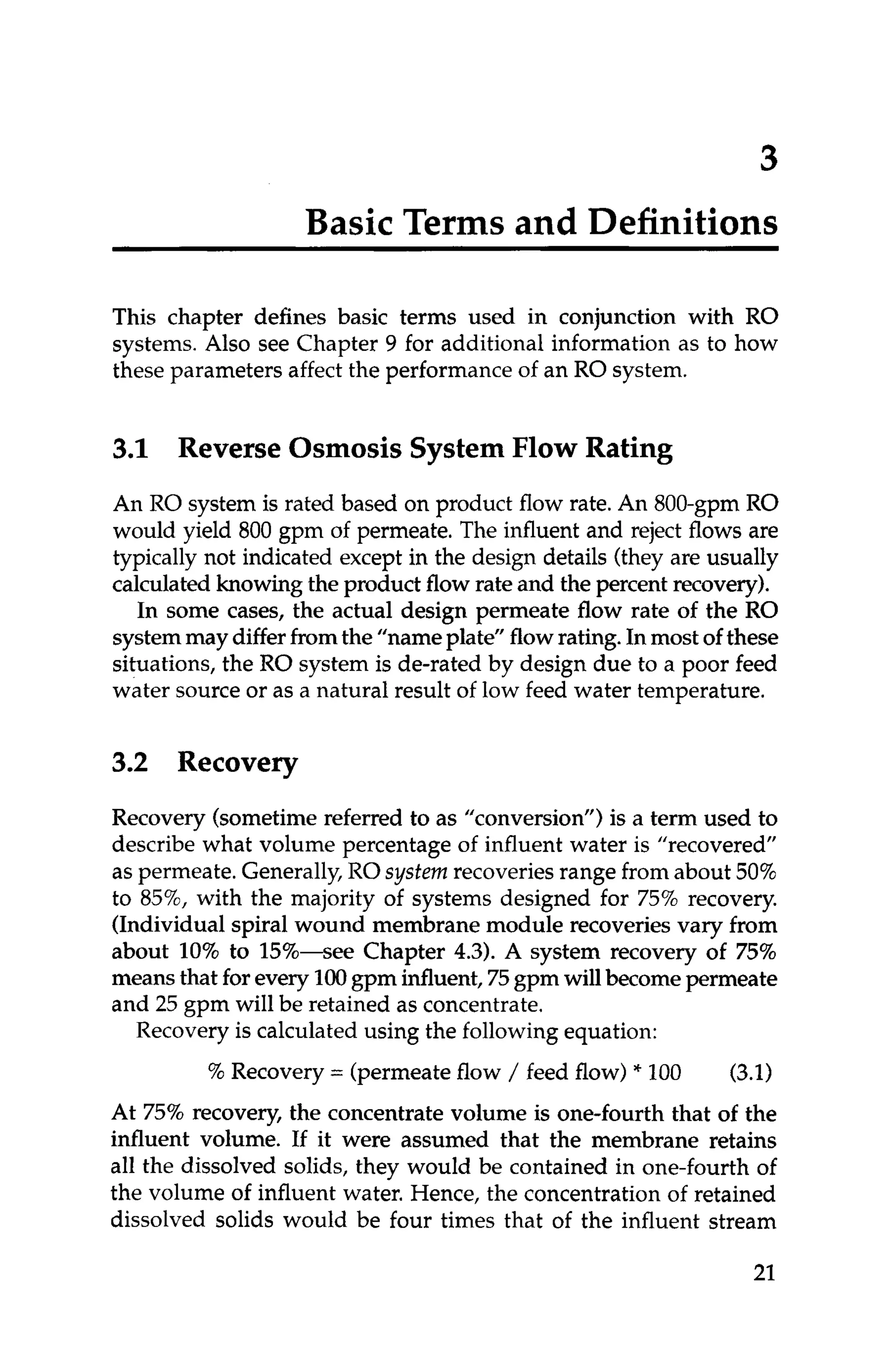

![BASICTERMS

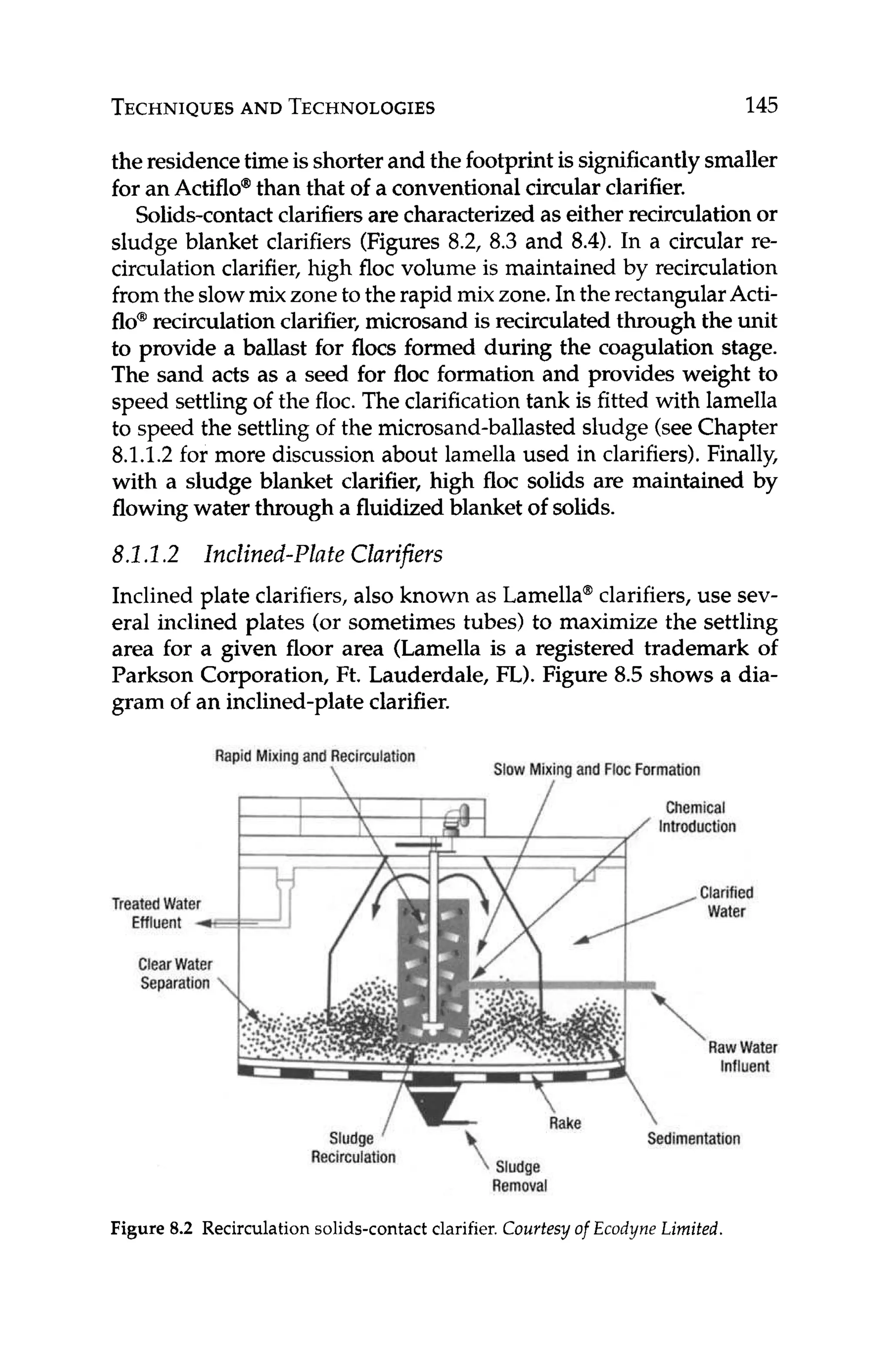

AND DEFINITIONS 23

-

Instantaneous Pppm

Permeate

Concentration

98% Rejection Membrane

Feed / Concentrate 100 ppm 200 400

Concentration

Recovery 0% 50% 75%

-

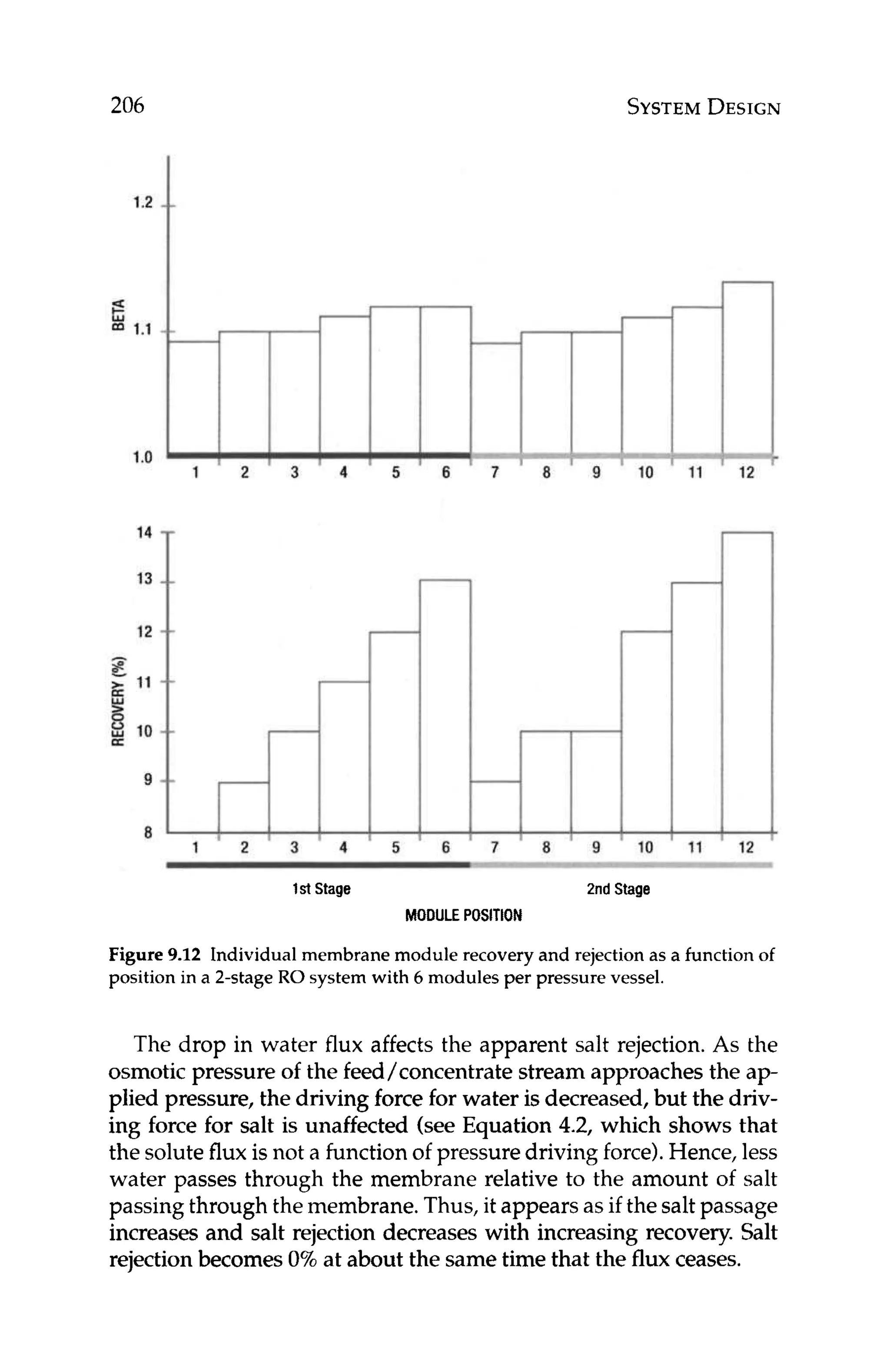

Figure 3.1 Concentrateand instantaneouspermeate concentration as functions

of recovery.

In practice, the recovery of the RO system is adjusted using

the flow control valve located on the RO concentrate stream (see

Figure 2.6).Throttlingthe valve will result in higher operating pres-

sure, which forces more water through the membrane as opposed

to down along the feed/concentrate side of the membrane, and

results in higher recovery.

Therecovery of an ROsystem is fixed by the designer.Exceeding

the design recovery can result in accelerated foulingand scaling of

the membranes, because less water is available to scour the mem-

brane on the concentrate side. Falling below the design recovery

will not adversely impact membrane fouling or scaling, but will

result in higher volumes of wastewater from the RO system.

3.3 Rejection

Rejection is a term used to describe what percentage of an influent

species a membrane retains. For example, 98% rejection of silica

means that the membrane will retain 98% of the influent silica. It

alsomeans that 2%of influentsilica will pass through the membrane

into the permeate (known as "salt passage").

Rejection of a given species is calculated using the following

equation:

(3.2)

% Rejection = [(C,

- Cp)/C,]

* 100

C,= influent concentrationof a specific component

Cp= permeate concentrationof a specific component

where:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-45-2048.jpg)

![34 FUNDAMENTALS

Ascaledmembraneexhibitsthreemajorperformanceissues:high-

er than normal operating pressure (to compensate for lower flux at

constant pressure), higher pressure drop, and lower than expected

salt rejection. As with fouled membranes, scale forms an additional

barrier layer through which water has to travel. Additional driving

force is required to push water through this barrier layer if the same

productivity is to be maintained. Higher pressure drop is due to re-

sistance of the scale to cross flow. Lower salt rejection is a function

of concentrationpolarization,in that the concentrationof the scaled

mineral is higher at the membrane surfacethan in the bulk solution.

Thus, the membrane "sees" a higher concentration, and, although

the intrinsicrejection by the membrane remains constant,the actual

amount of a solute that passes through the membrane is greater (see

Equation 4.2, which predicts that the flux of a solute through an RO

membrane is a functionof the concentrationdifferencebetween the

solute in the boundary layer and in the permeate).Hence, the appar-

ent rejection is lower and product purity is lower.

Since scaling is a concentration phenomenon, it goes to reason

that scale would be most likely found in the last stages of an RO

system where the concentrationof salts is the highest. To determine

the potential for a salt to form scale, the ion product of the salt in

question (taken in the reject stream) is compared with the solubility

product for the salt under the conditions in the reject.

Equation 3.7defines the ion product at any degree of saturation:

IP = [cati~n]~[anion]~ (3.7)

Where:

IP = ion product

[cation]= cation concentration

[anion] = anion concentration

Superscripts:

a = the quantity of cation present within the salt

b = the quantity of anion present within the salt.

Equation 3.8defines the solubility product at saturation:

KSp= [cationIa[anionlb

where:

KSP

= solubility product

[cation]= cation concentration

[anion]= anion concentration

(3.8)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-56-2048.jpg)

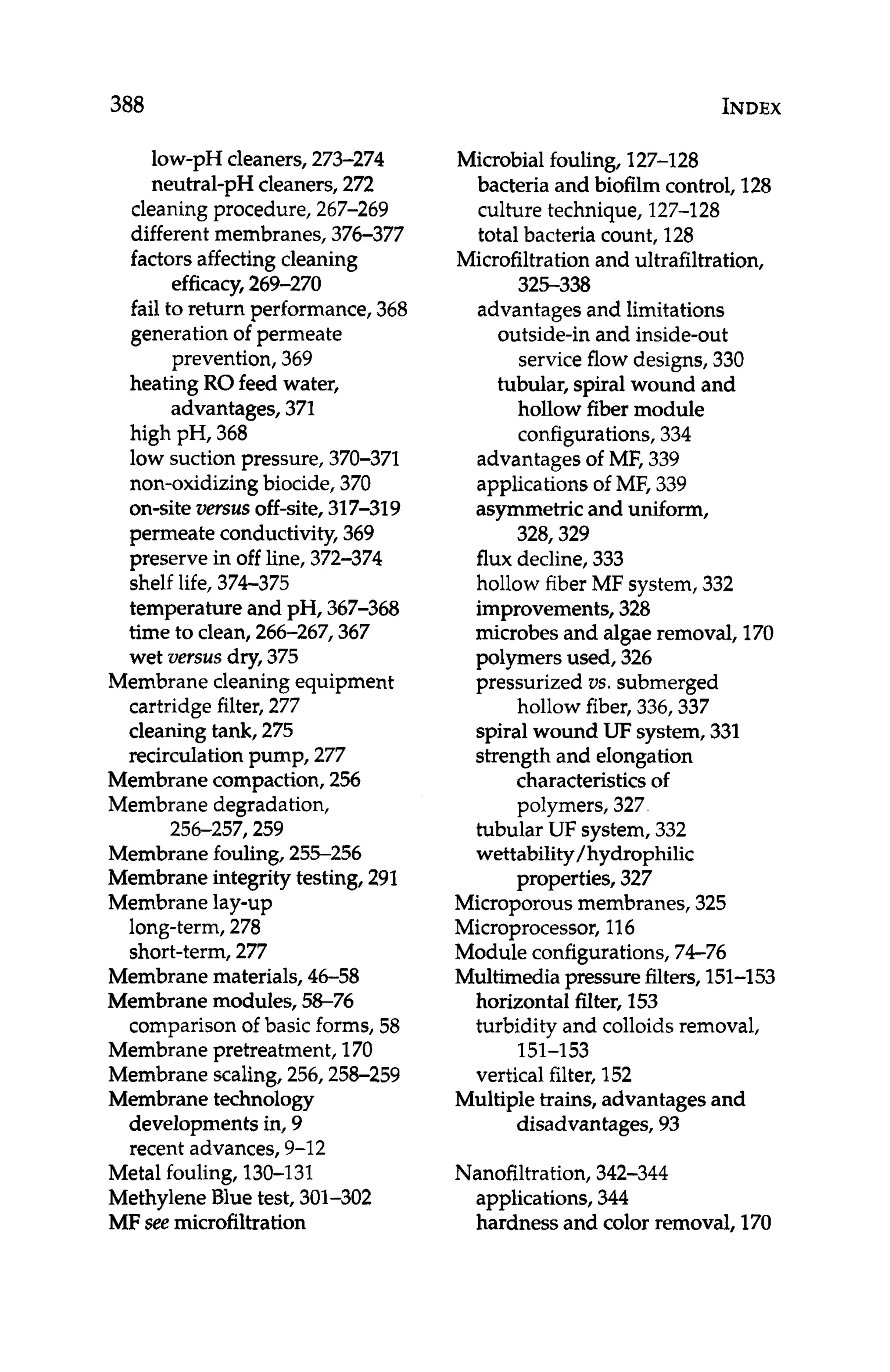

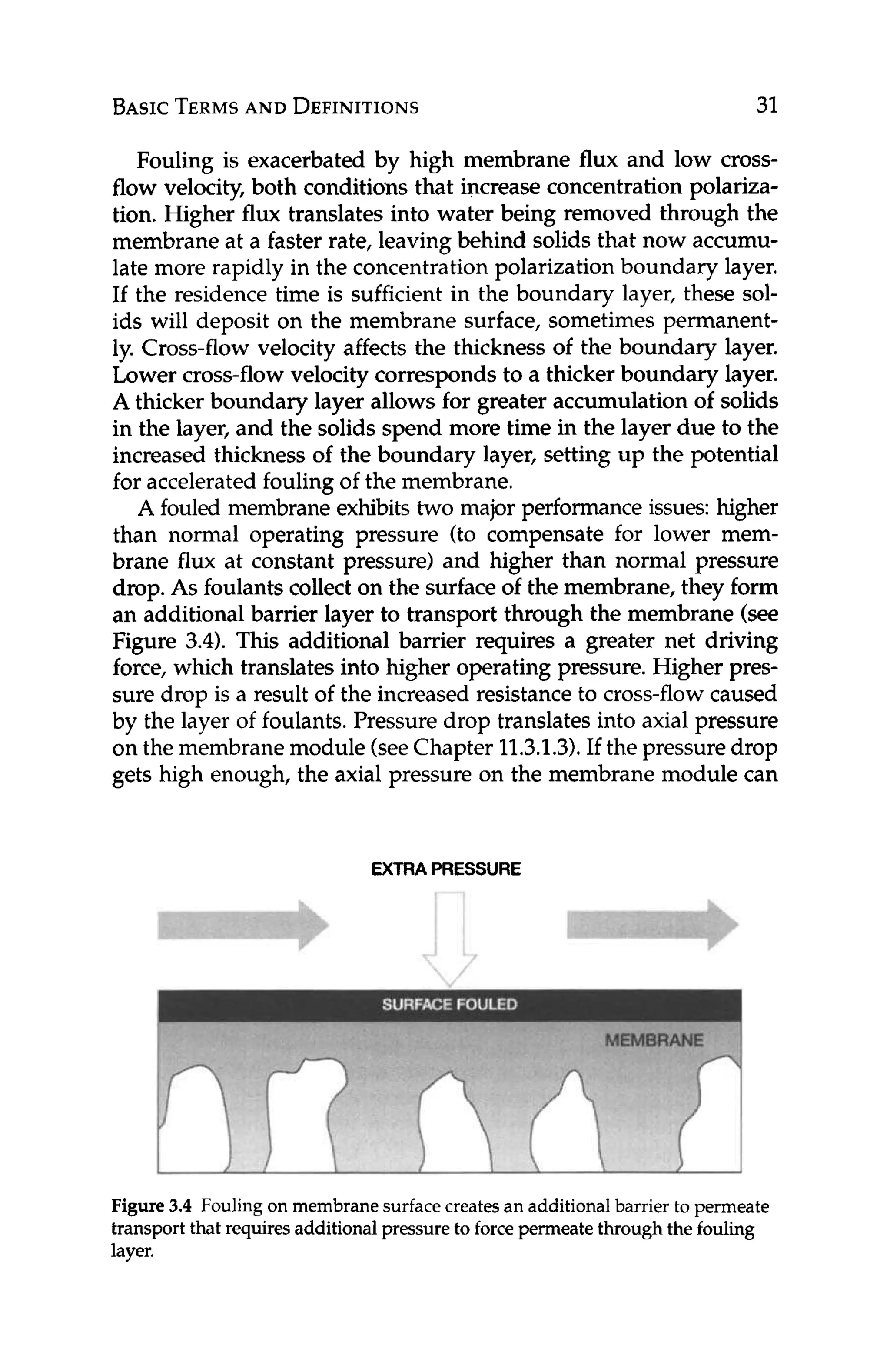

![38 FUNDAMENTALS

I

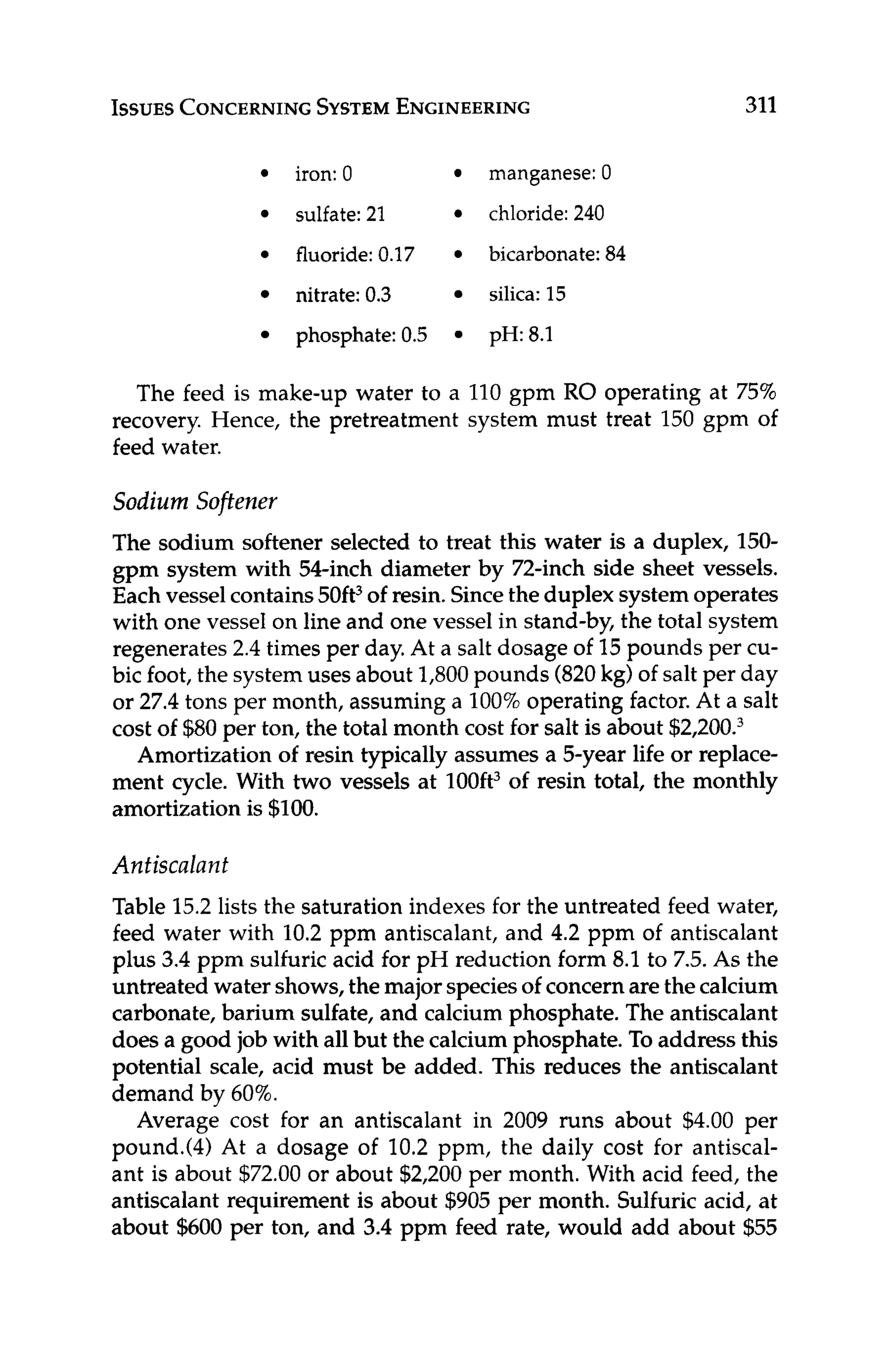

Figure 3.7 Silt density index pads taken before and after a filter treating RO

influent water.

The SDI filter pads can also be sent into a lab for analysis of the

deposit. The results of the deposit analysis will aid in the devel-

opment of an appropriate pretreatment scheme, as specific species

contributing to the suspended solids loading can be targeted for

treatment to reduce their concentration in the feed water to the RO.

3.10 Langelier Saturation Index

The Langelier Saturation Index (LSI) is a method for quantifying

the scalingor corrosion tendency of water. It was originally applied

to cooling water. The LSI is based on the pH and temperature of

the water in question as well as the concentrations of TDS, calcium

hardness, and alkalinity.

Langelier Saturation Index is calculated using equation 3.10:

LSI = pH - pHa

pH, = (9.30+ A + B) - (C + D)

(3.10)

where:

(3.11)

and:

A = (Log,,[TDSl - 1)/ 10, where [TDSIis in ppm

C = Log,,[Ca2+]

- 0.4, where [Ca”] is in ppm CaCO,

D = Log,,[alkalinityl, where [alkalinity]is in pprn CaCO,

B = -13.12 x Log,,(OC+ 273) + 34.55](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-60-2048.jpg)

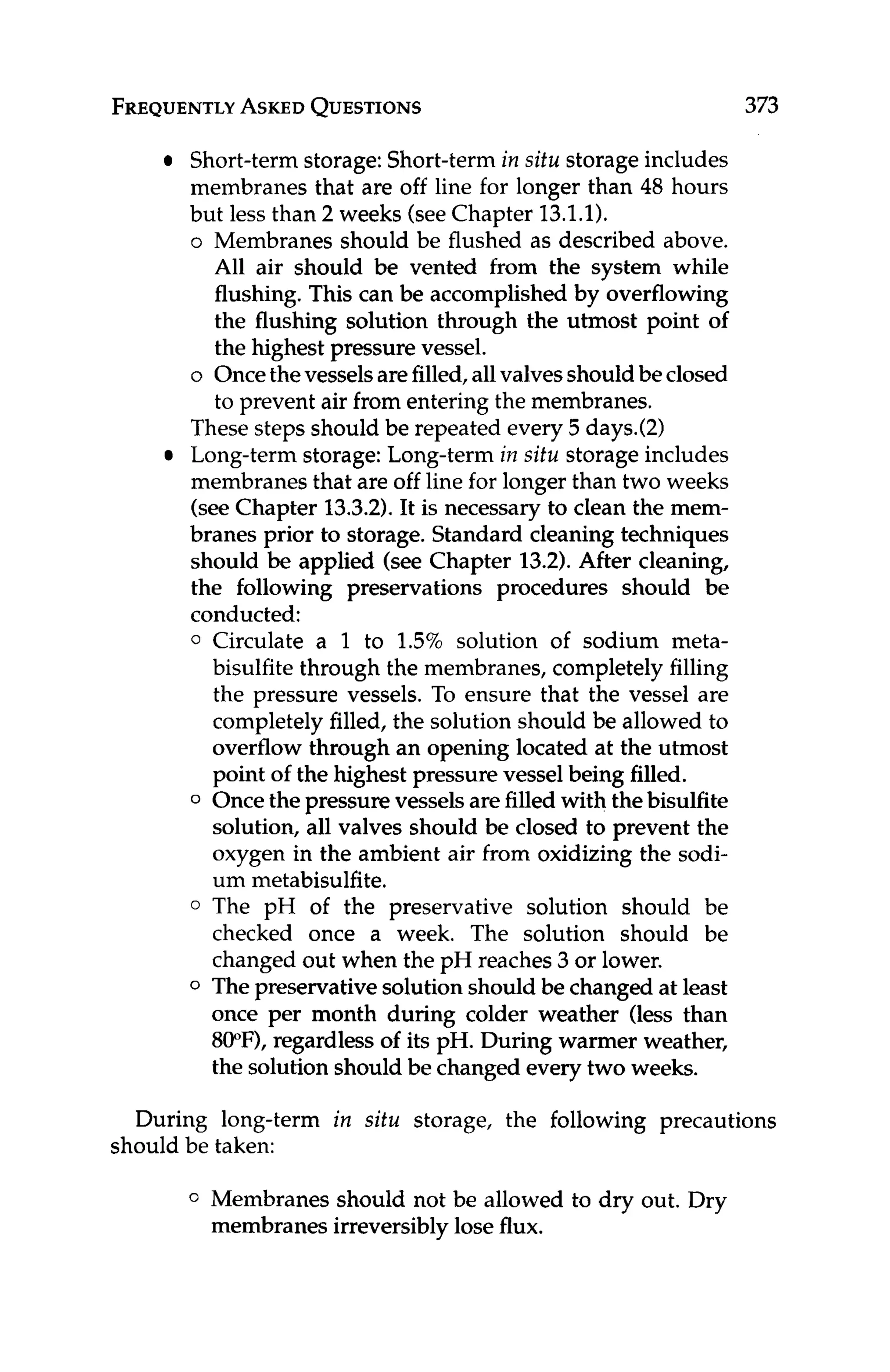

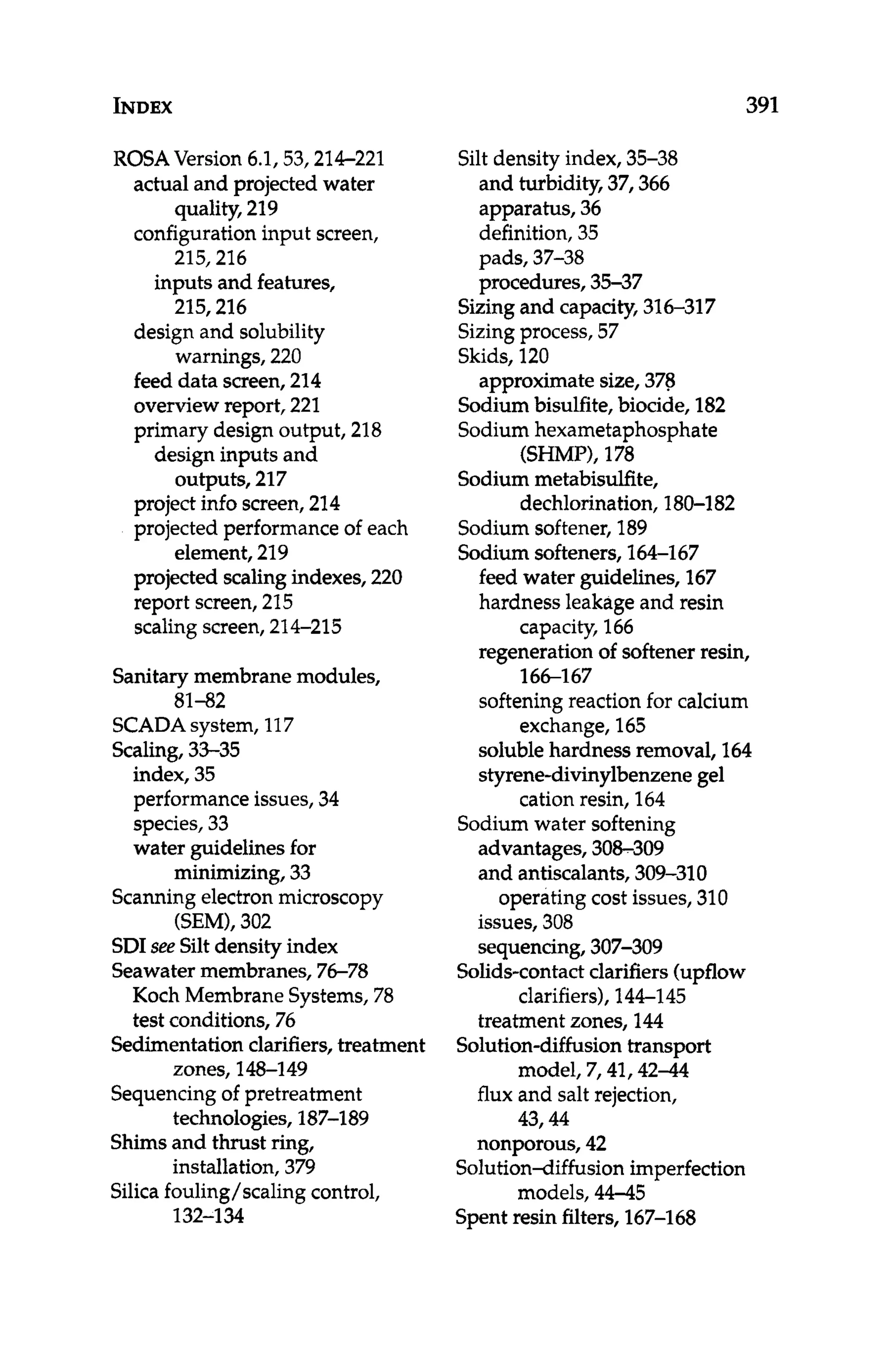

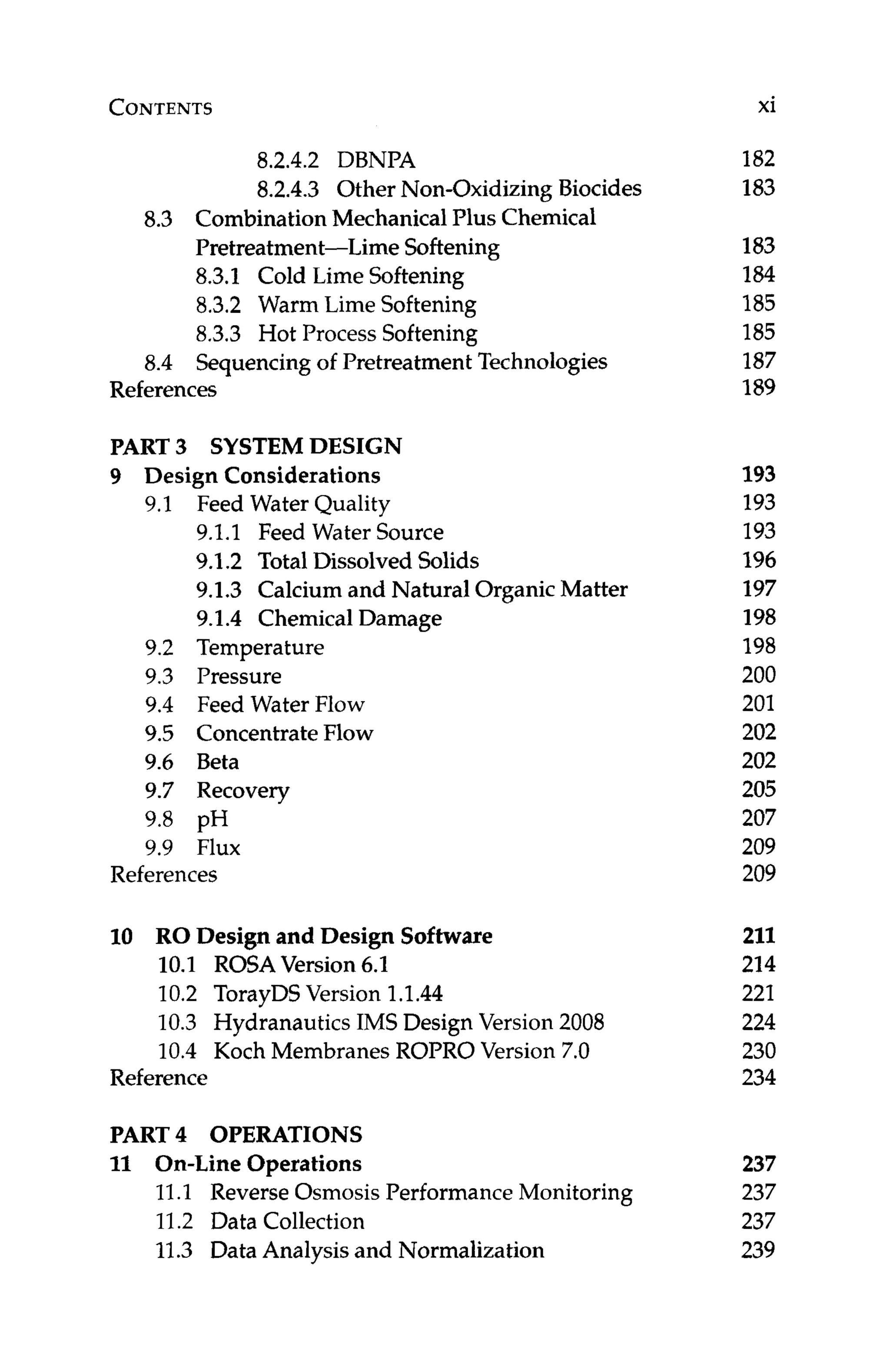

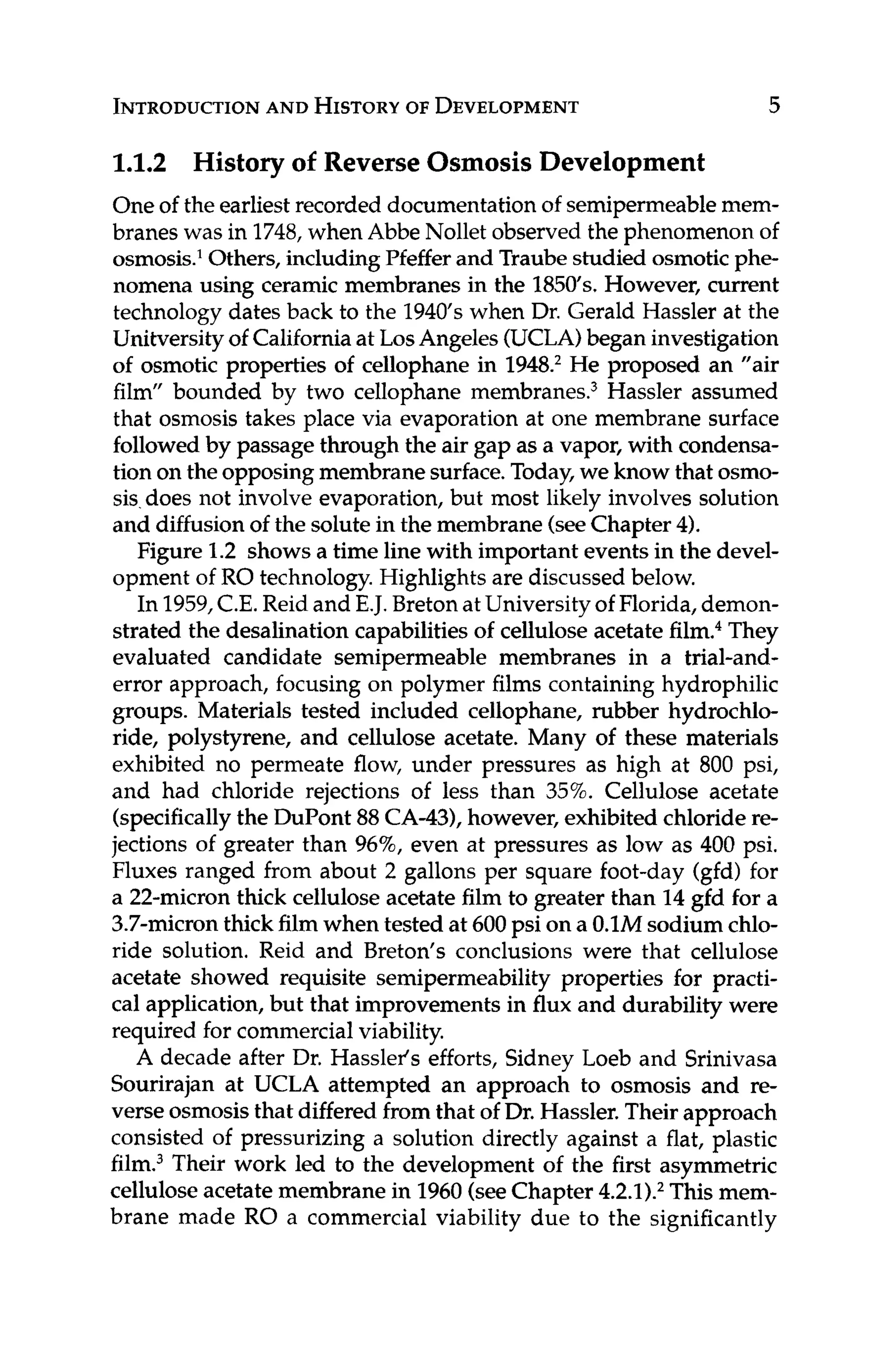

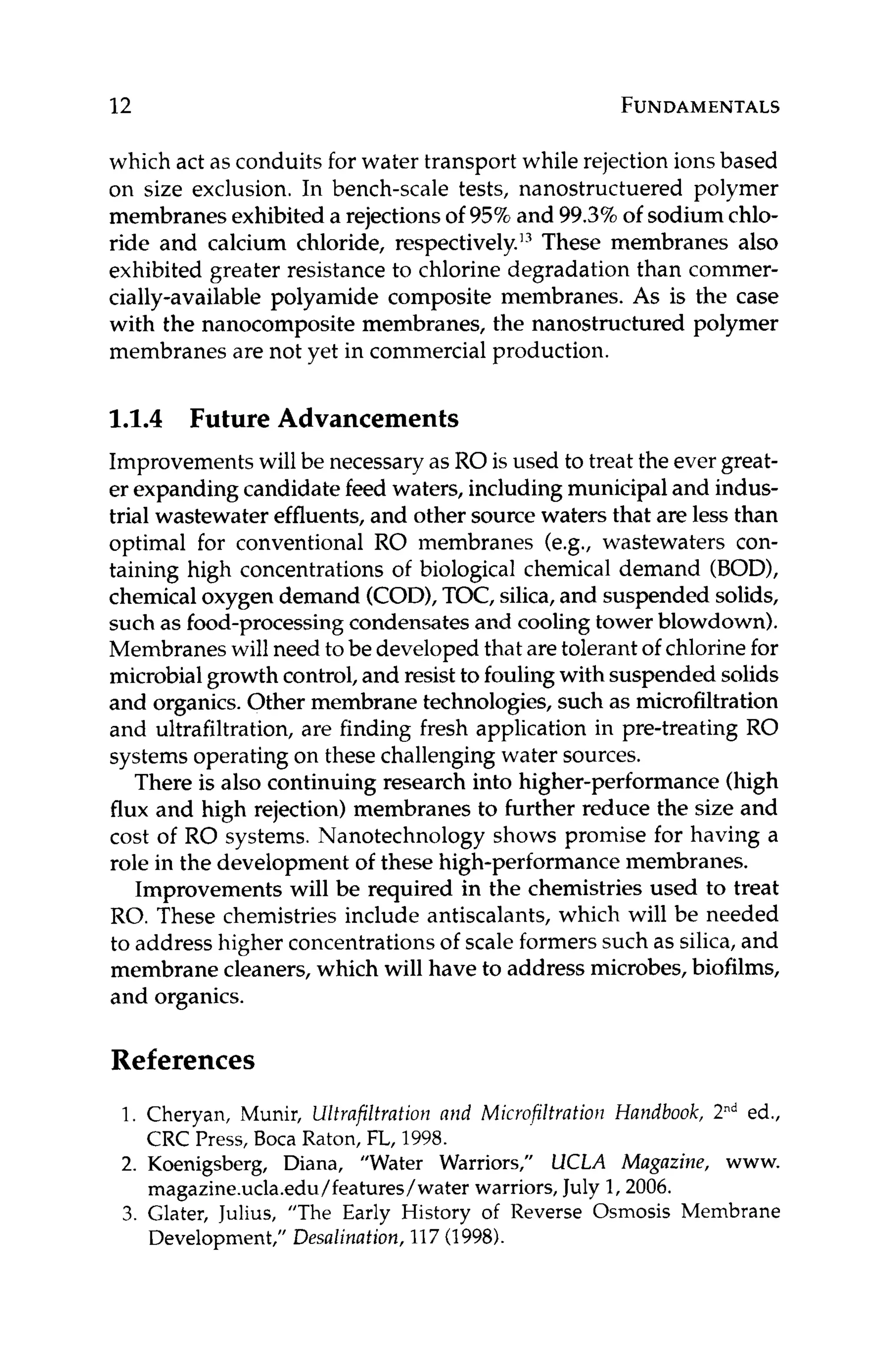

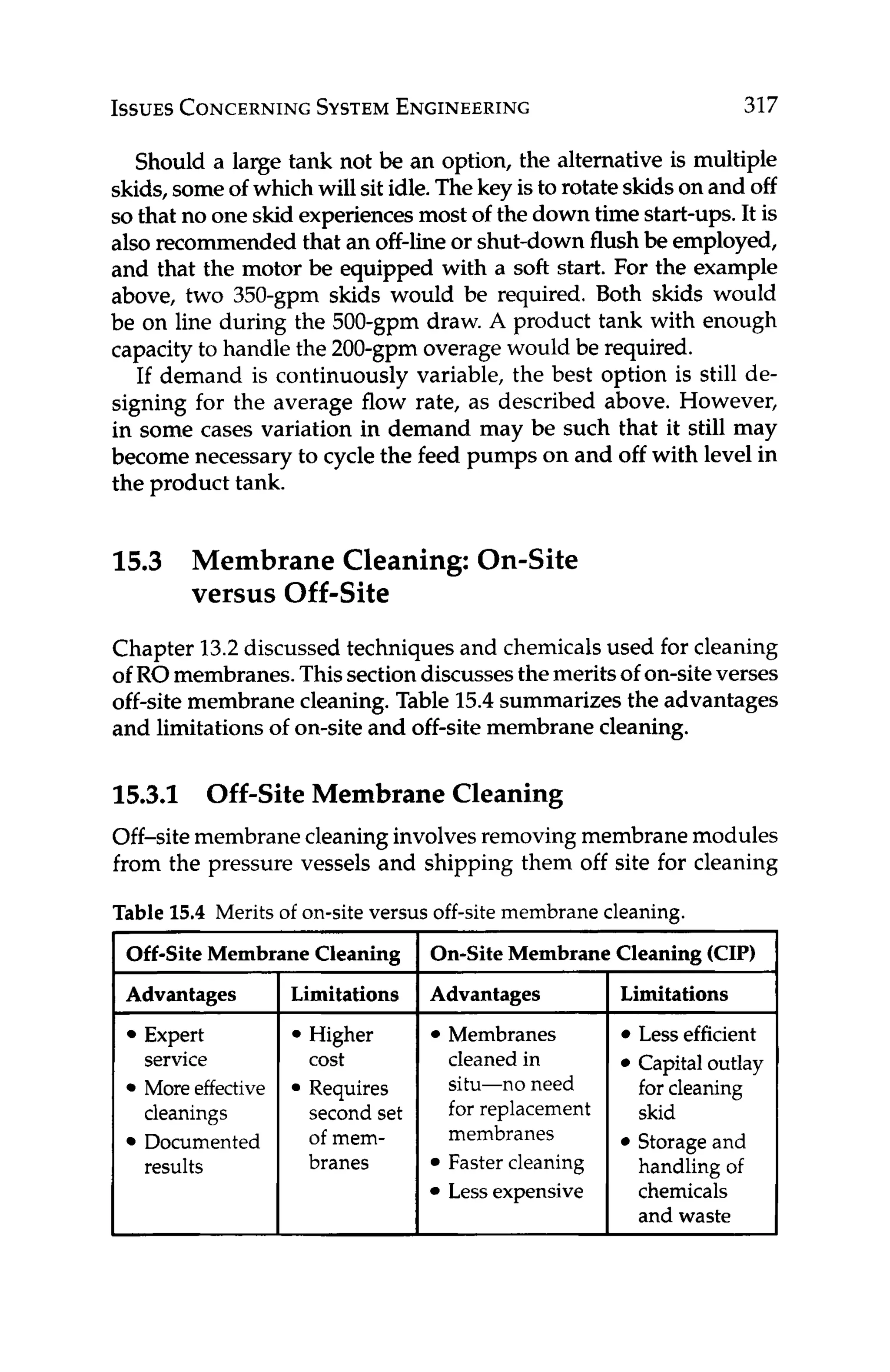

![BASICTERMS

AND DEFINITIONS 39

LSI

3.0

2.0

1.o

0.5

0.2

0.0

-0.2

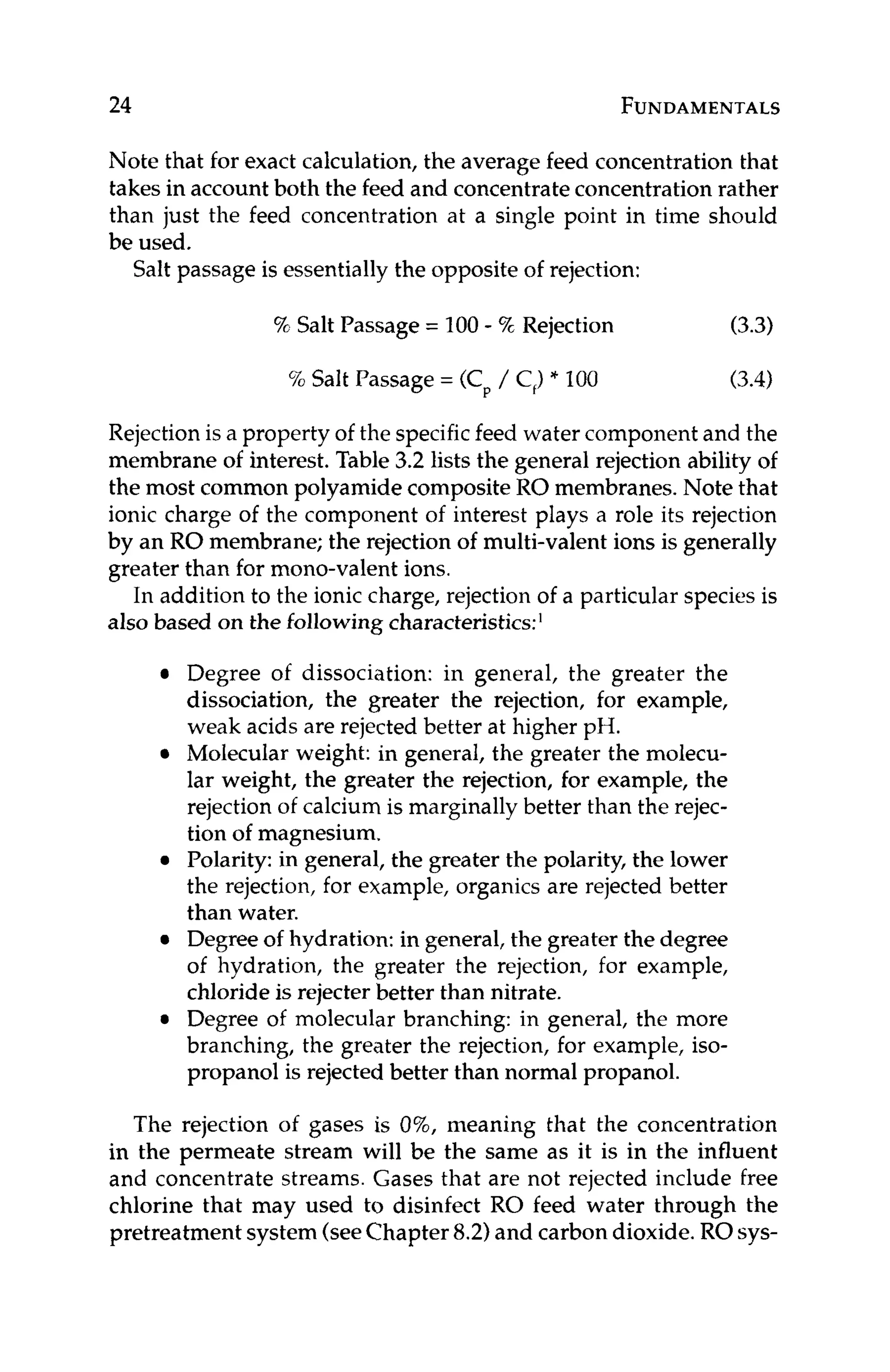

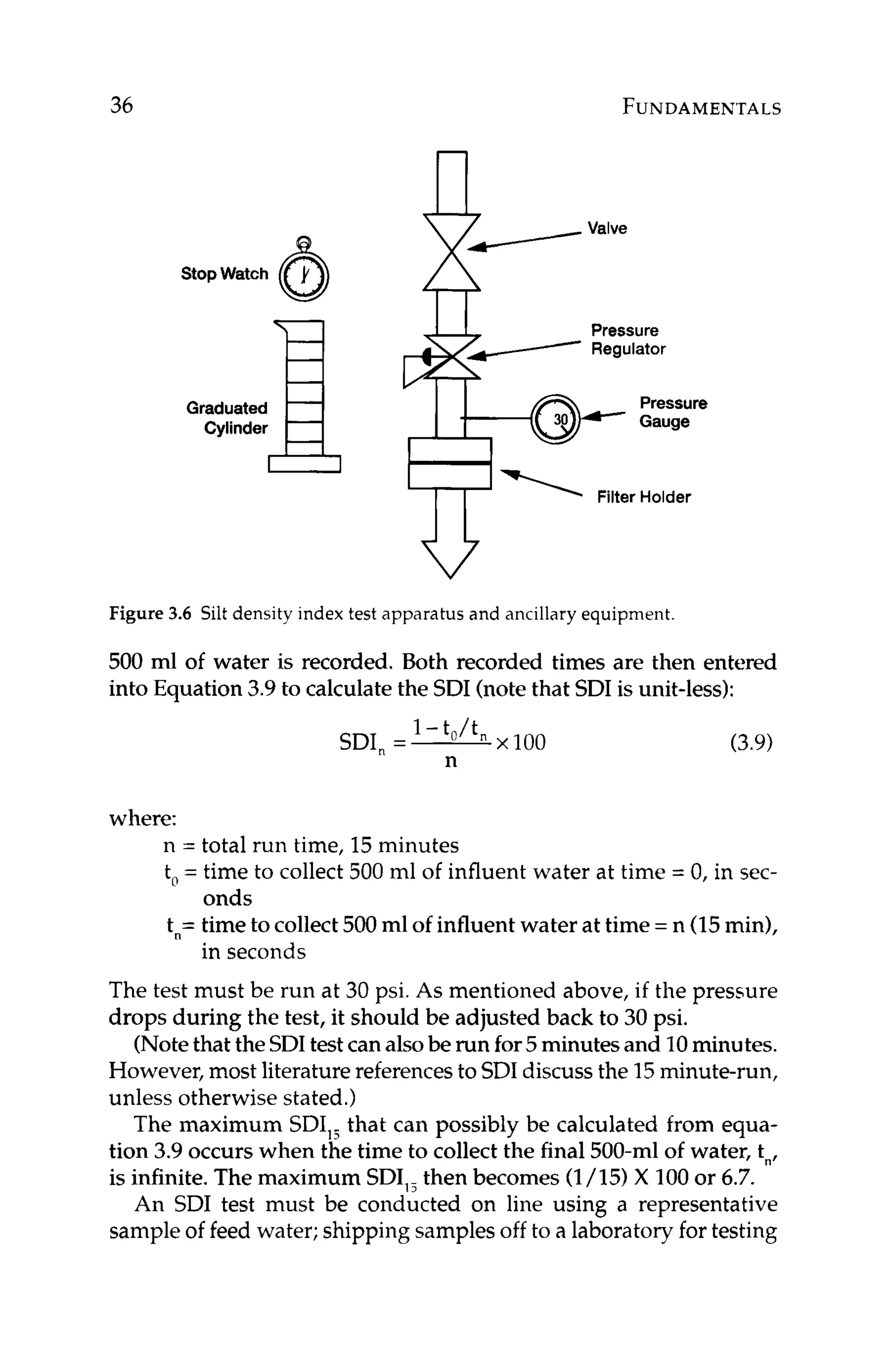

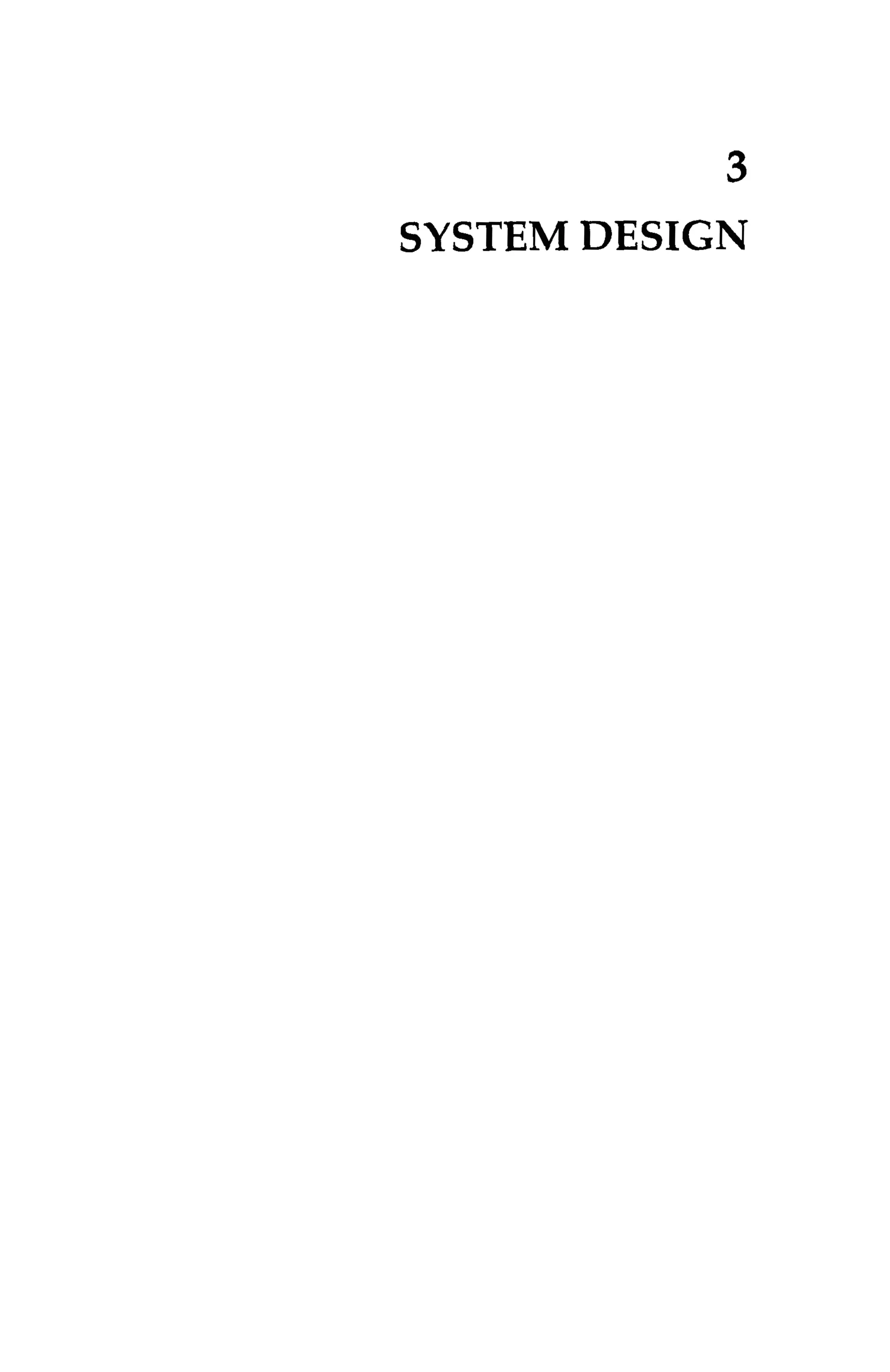

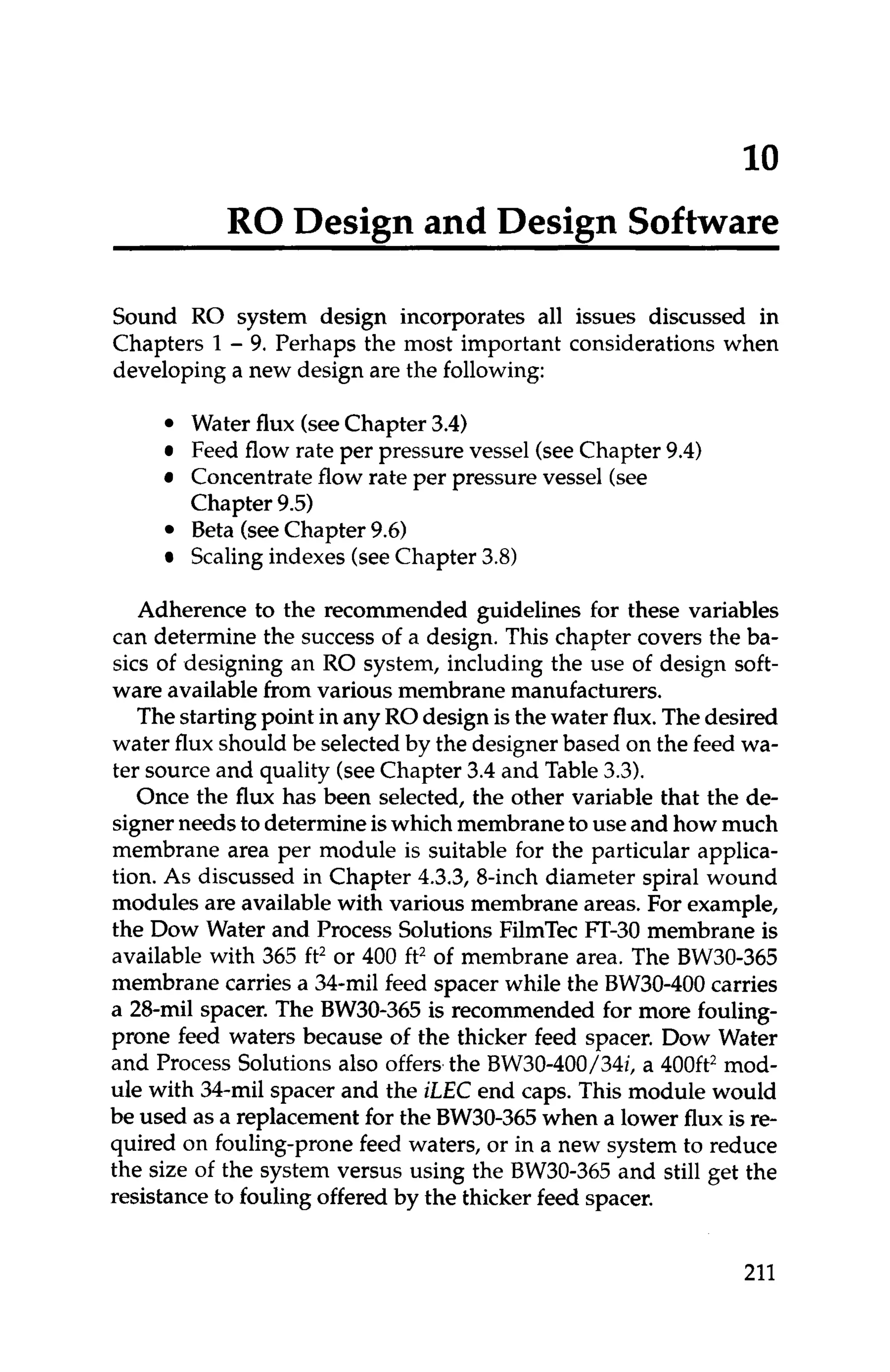

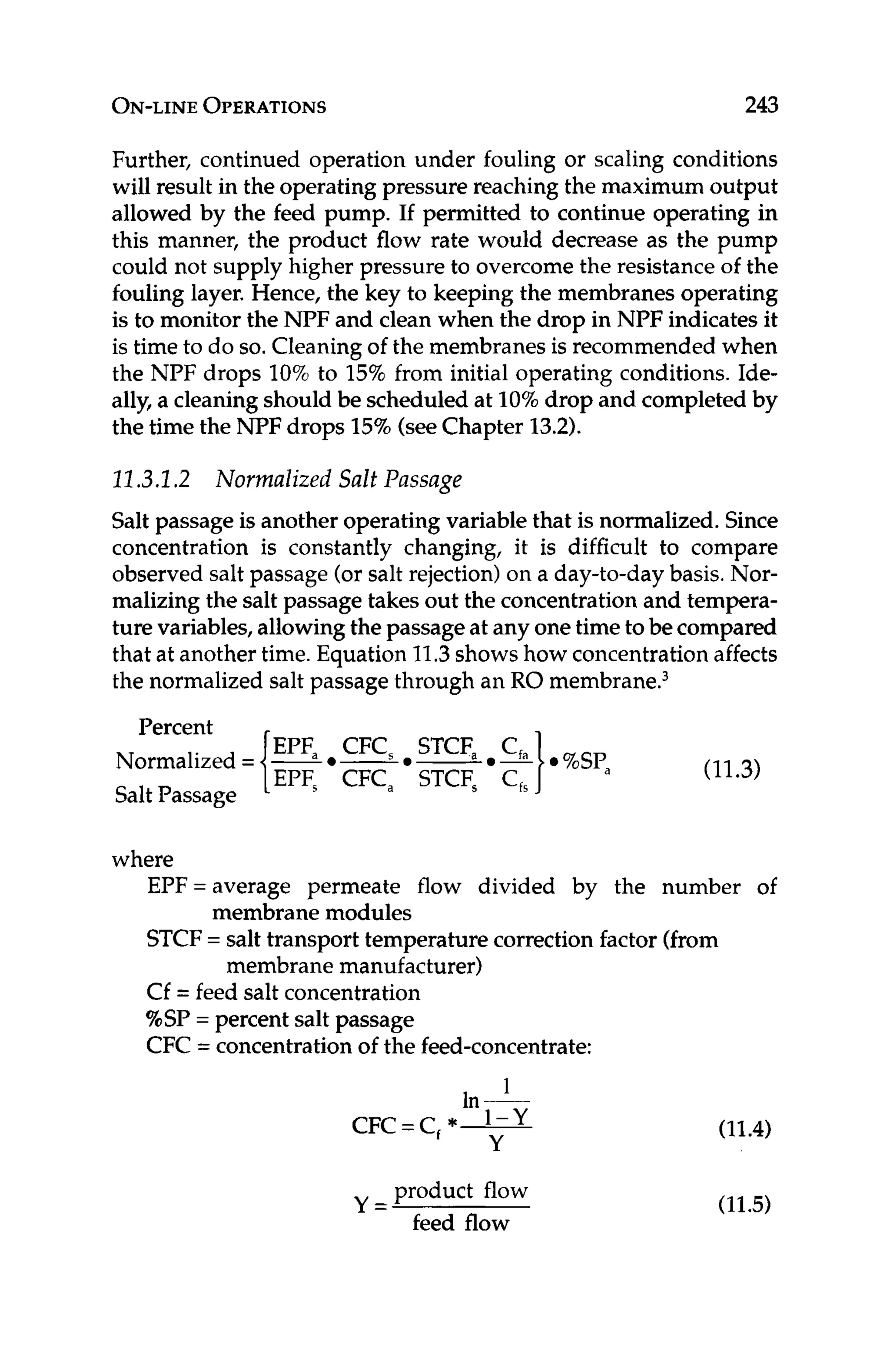

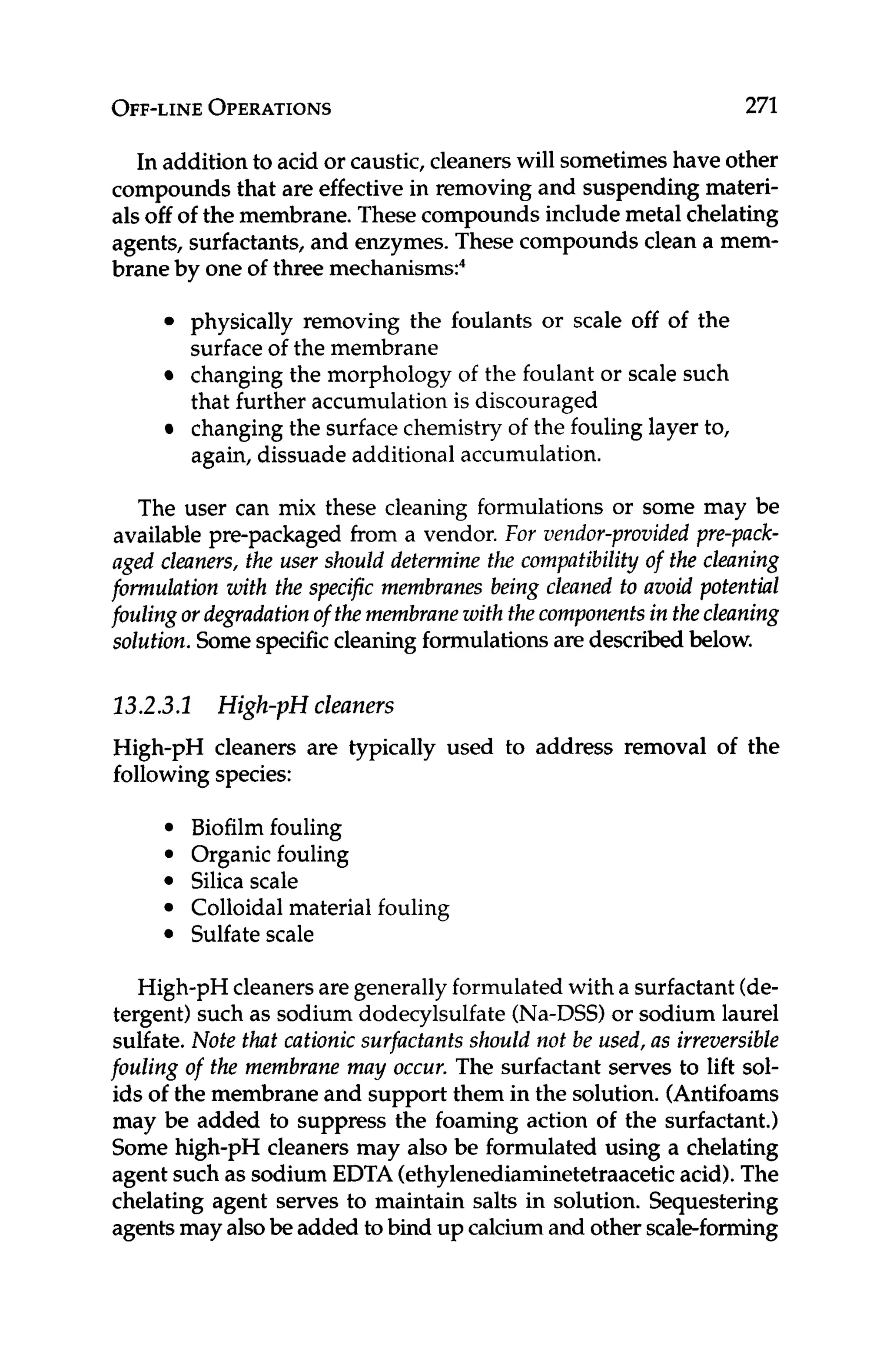

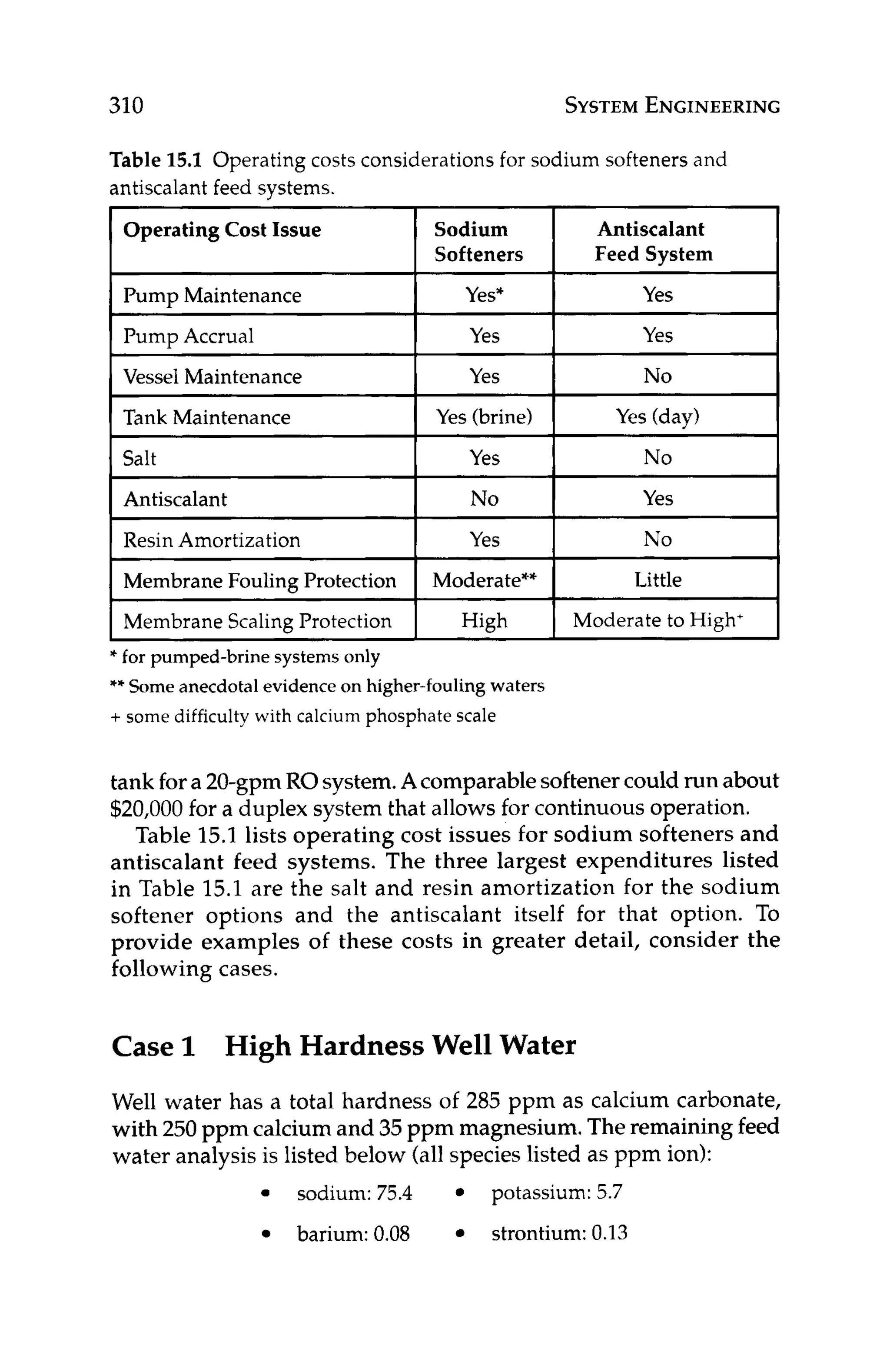

Table 3.6 Langelier saturation index.

Condition

Extremely severe scaling

Very severe scaling

Severescaling

Moderate scaling

Slight scaling

Stable water (noscale)

No scale, very slight tendency to dissolve scale

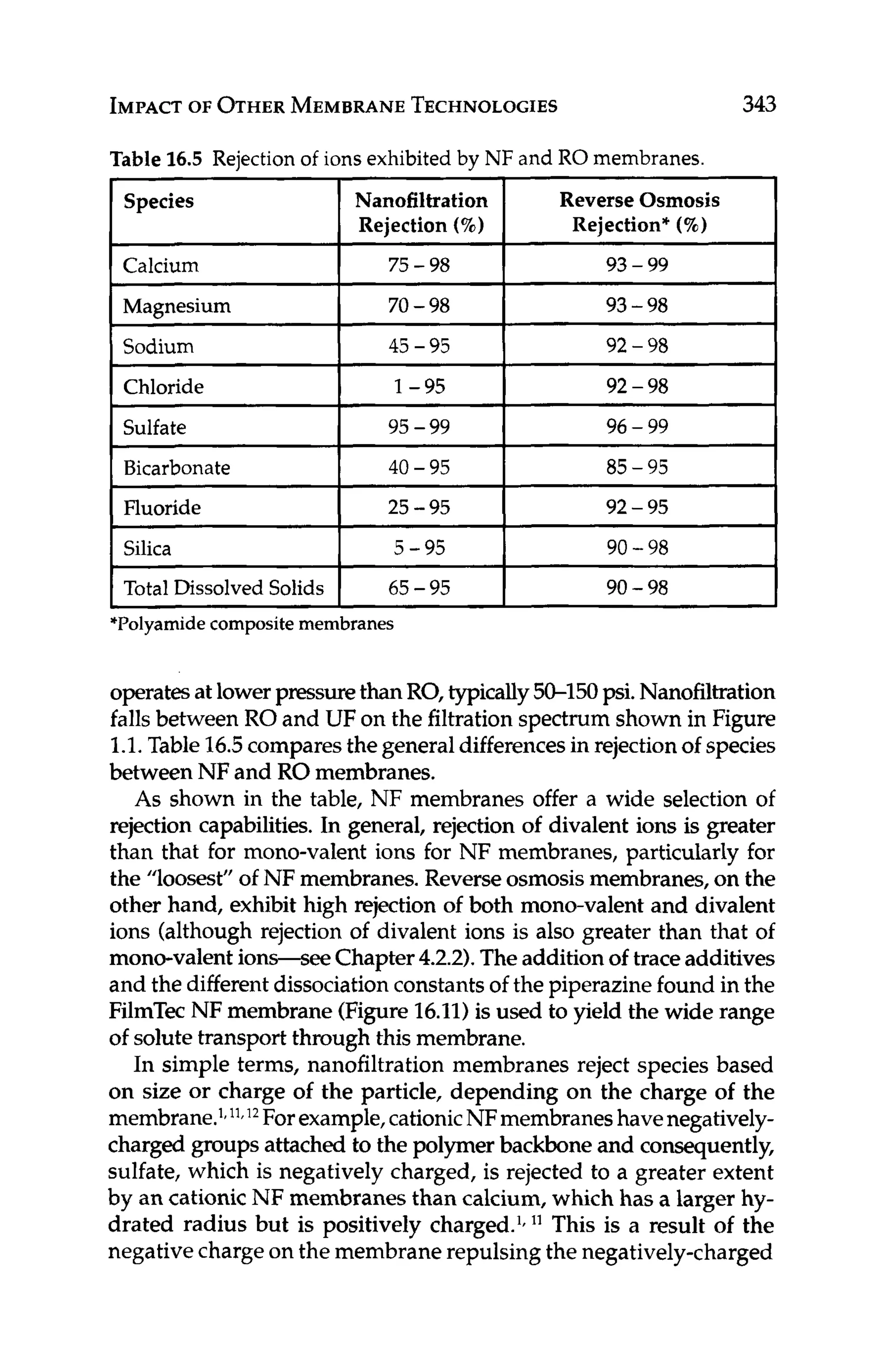

If LSI is greater than 0, the water has the tendency to form

calcium carbonate scale. If the LSI is equal to 0, the water is in

chemical balance. If the LSI is less than 0, the water is corrosive

(refer to Table 3.6).

Langelier Saturation Index is valid up to about 4,000 ppm TDS.

At higher TDS concentrations, the Stiff-Davis Saturation Index

(SDSI)is used, Equation 3.12:

SDSI = pH -pCa - pArK

- K (3.12)

where:

pCa =-Log10[Ca2+],

where [Ca2+l

is in ppm

pAlk

= -LoglO[total alkalinity],where alkalinity is in ppm

K = a constant based on the total ionic strength and

temperature

For RO applications,a positive LSI or SDSIindicates that the influ-

ent water has a tendency to form calcium carbonate scale. In these

cases, pretreatment in the form of softening(eitherwith lime or ion

exchange),or via the use of antiscalantsand/or acid is required.

References

1. Dow Chemical Company, FilmTec Reuerse Osmosis Membranes Technical

Manual, Form no. 609-00071-0705, Dow Liquid Separations,2007.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-61-2048.jpg)

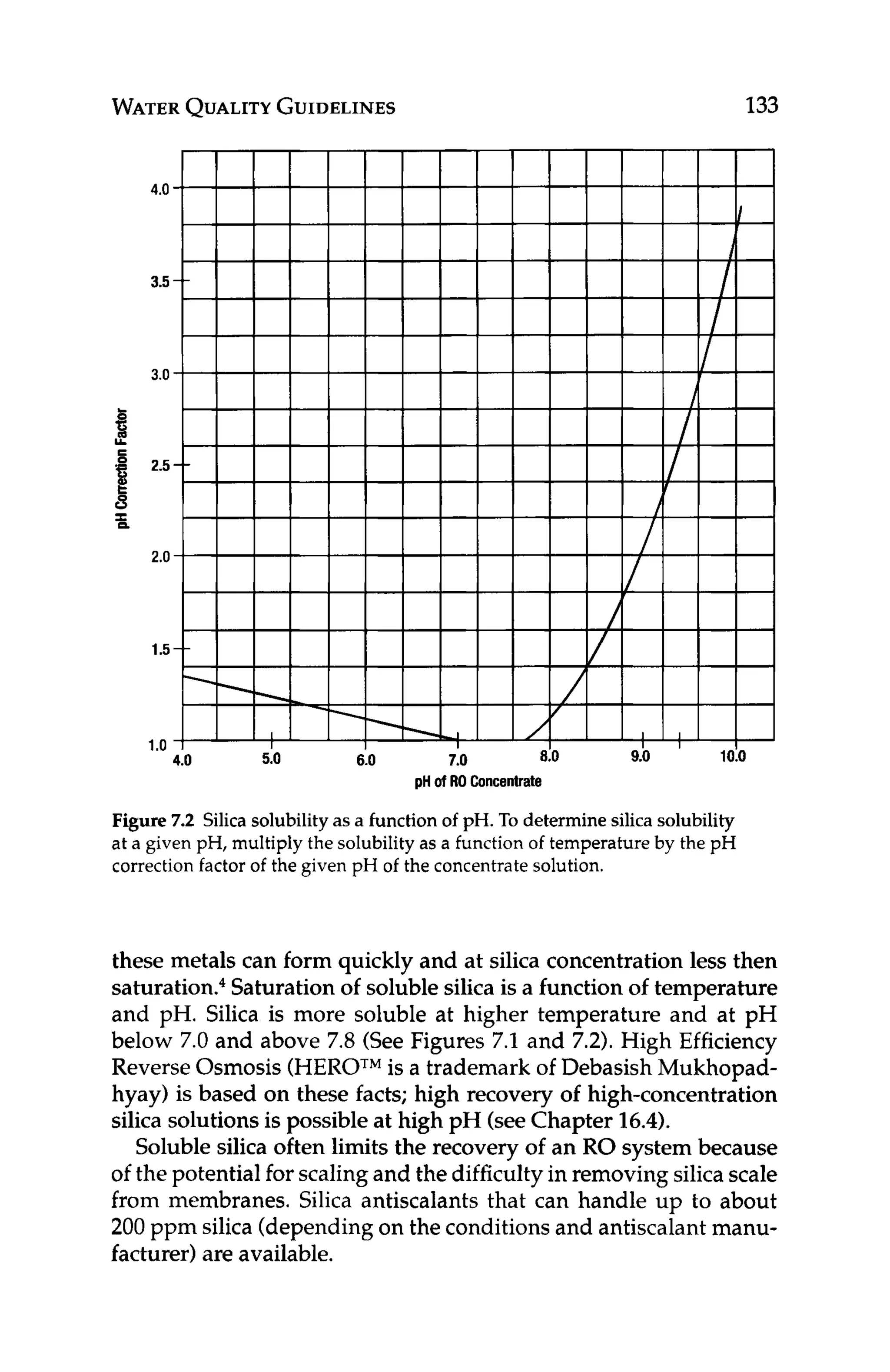

![134 PRETREATMENT

Silica fouling causes high pressure drop and low productivity.Silica

scalingcauses low rejection of silica and perhaps other ions as well.

Colloidal silica can be removed or reduced in RO feed water us-

ing coagulation/clarification (see Chapter 8.1.1). Soluble silica is

typically dealt with using high pH, elevated temperature, antiscal-

ants (see Chapter 8.2.3),or the HEROTM

process. Sometimes, the

recovery of the RO system is adjusted to minimize the potential for

forming silica scale.

7.8 Calcium Carbonate

Calcium carbonate scalingis perhaps the most common type of prob-

lem, with the possible exception of microbial fouling, that RO mem-

branes experience. Fortunately,it is fairly easy to detect and handle.

Basically, if the ion product (IP)of calcium carbonate in the RO re-

ject is greater than the solubility constant (KSJ under reject conditions,

then calciumcarbonate scalewill form. If IP < K ,scalingin unlikely.

The ion product at any degree of saturation is def%ed as:

IP = [cationla[anionlb (7.3)

where:

IP = ion product

[cation]= cation concentration

[anion]= anion concentration

superscripts:

a = quantity of cation within the salt

b = quantity of anion within the salt

The solubility product at saturation is defined as:

KSp= [cationla[anionlb

where:

KSp= solubility product

(7.4)

Langelier Saturation Index (LSI) is used to determine the scaling

potential of calcium carbonate. (Note that LSI is used up to about

4,000 ppm TDS; higher concentrations rely on the Stiff-Davis Satu-

ration Index.) The LSI is calculated using the following formulas](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-156-2048.jpg)

![WATER

QUALITY GUIDELINES 135

(notethat the concentrateconcentrationis used to calculatethe LSI,

as this is where the concentrationsof solutes is the greatest):

(7.5)

(7.6)

LSI = pH - pHa

where:

pHa= (9.30+ A+ B) - (C +D)

where:

A = (log,,[TDS] -11/10

B = -13.12 x lOg,,(OC+273) + 34.55

C = log,,[Ca2+]

-0.4, where [Ca2+l

is in ppm as CaCO,

D = log,,[alkalinity], where [alkalinity]is in ppm as CaCO,

A positiveLSI means that scalingis favored;a negativeLSI means that

corrosionisfavored.It isdesirableto keeptheLSI near zero(orbelow)

in the RO concentrate to minimize calcium carbonate scaling. This

is usually accomplished by feeding acid to lower the pH or feeding

an antiscalant(seeChapter 8.2.3).Care must be given if sulfuricacid

is used to adjust the pH, as this may exacerbatesulfate-based scales,

such as calcium sulfate,barium sulfate,and strontiumsulfate.

Alternatively,antiscalantscan be used to control calcium carbonate

scaleatLSIvaluesashigh as2.0-2.5,dependingon thespecificantiscal-

ants. Calcium also forms scales with fluoride, sulfate, and phosphate.

TheLSIwillnothelppredictthesescales;analysisof waterquality,using

theionproductand solubilityconstants,isrequiredtodeterminethepo-

tentialforscalingwithcalciumfluorideorcalciumphosphate.Antiscal-

ants currently availablecan addresscalcium fluorideand calcium sul-

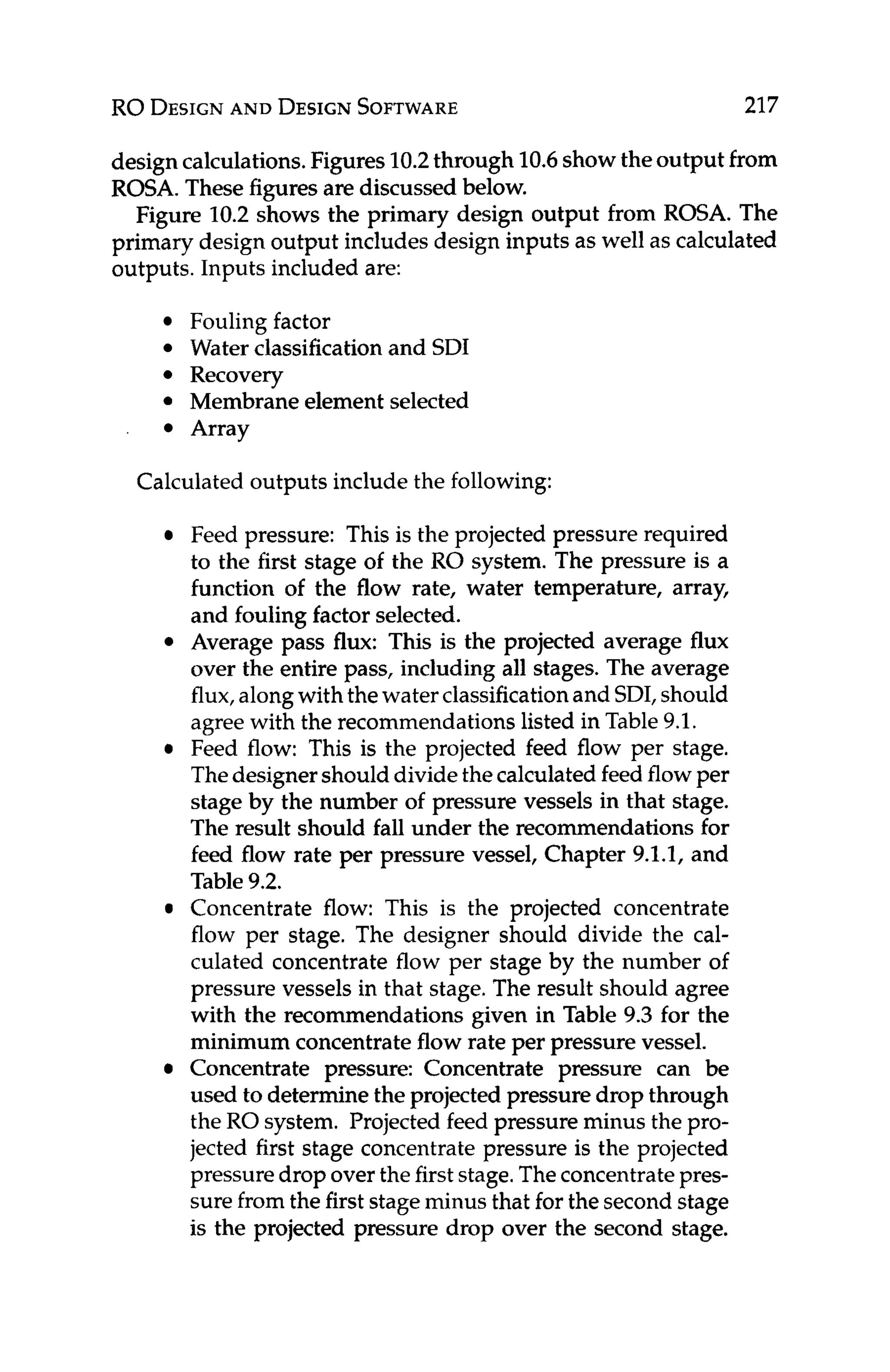

fatescale;theydonotaddresscalciumphosphatescale(althoughnewer

antiscalantswillbe availablein thenearfutureto addressthisscale).

Scaled membranes exhibit lower productivity and lower salt re-

jection. This lower salt rejection is a function of the concentration

polarization phenomenon (seeChapter 3.4).When membranes are

scaled, the surface of the membrane has a higher concentration of

solutes than in the bulk solution. Sincethe membrane rejects when

the membrane “sees,” the passage of salts will be higher, even

though the absolute or true rejection stays constant.

Calcium is removed from RO feed water using sodium soften-

ing, or reduced using lime softening(seeChapters 8.1.6and 8.3,re-

spectively).Dropping the LSI using acid is used to address calcium

scaling without removingor reducing the concentrationof calcium.

Antiscalantsarealsoused to address the issue without reducing the

amount of calcium present (seeChapter 8.2.3).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-157-2048.jpg)

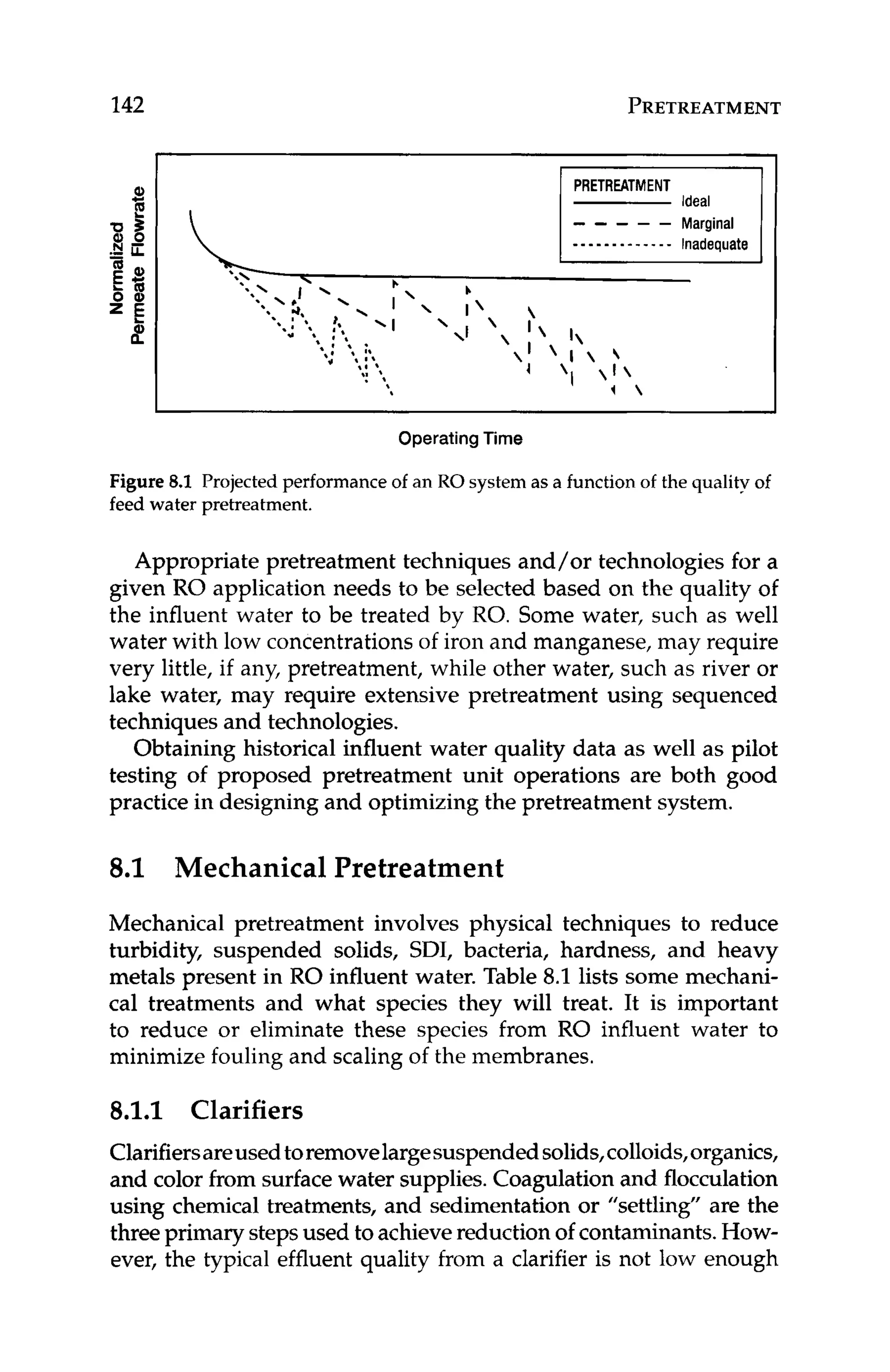

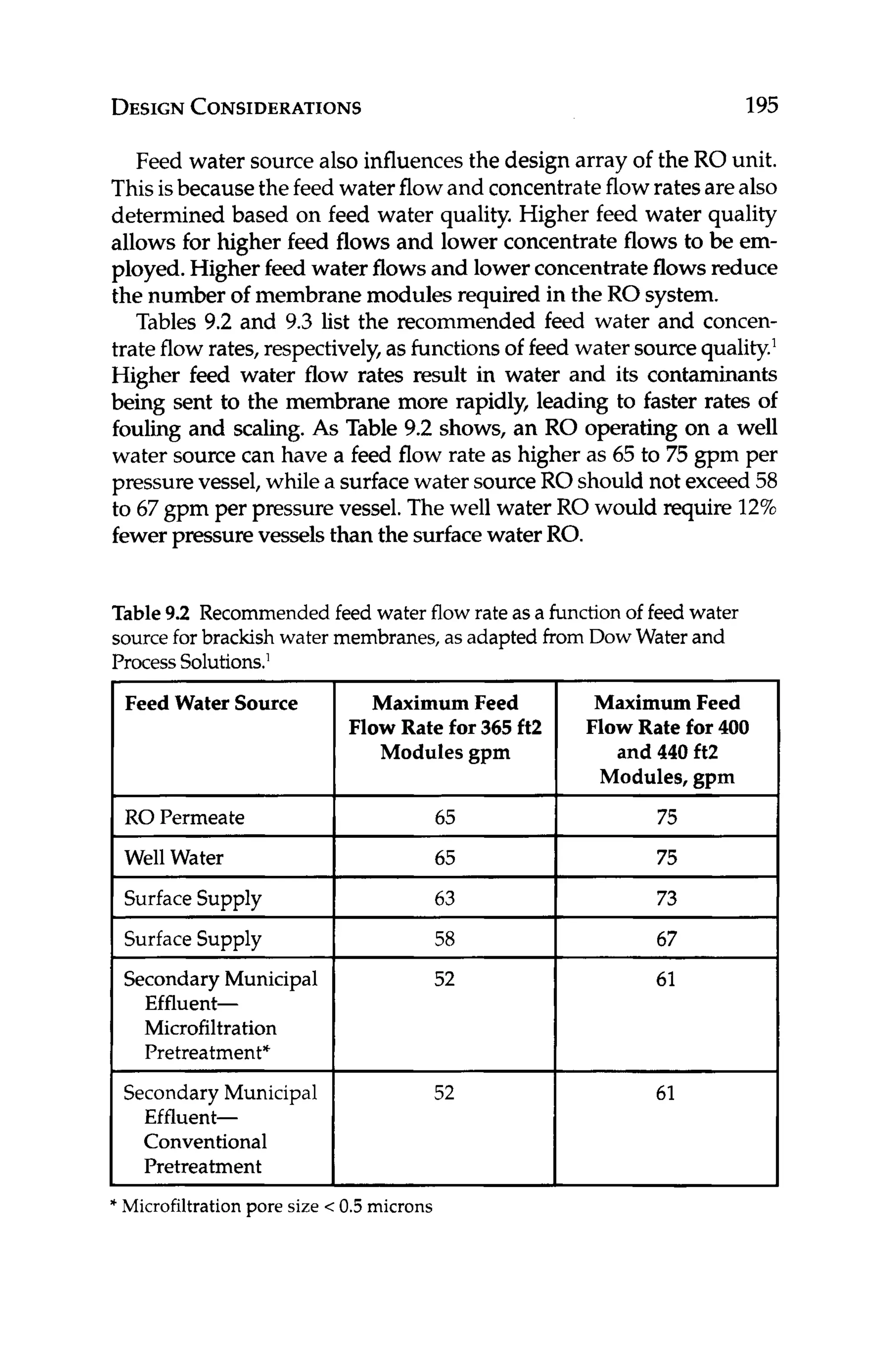

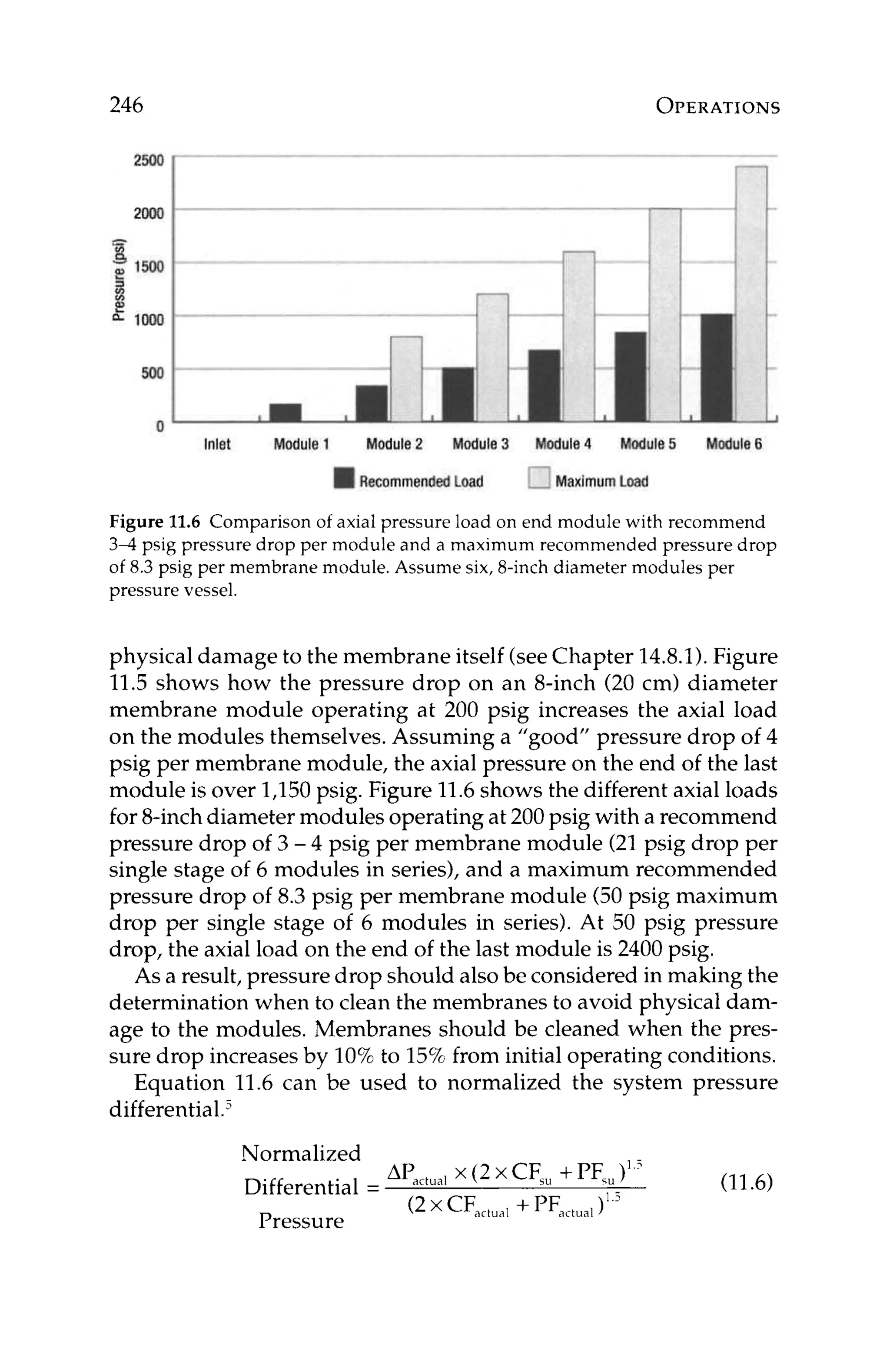

![212 SYSTEM

DESIGN

Having selected the appropriate water flux and membrane type,

the designer can use equation 10.1 to back calculate how many

membrane modules are required to meet the desired productivity.

J, = FP* 1/MA * 1/N (10.1)

where:

J,, = water flux, gfd

F = product flow rate, gallons/day

N = number of modules

MA = membrane area per module

Solvingequation 10.1for the number of modules, N, can give the

designer an idea of what the array might look like. For a two-stage,

75% recovery system with a tapered design, 2 / 3 of the total num-

ber of modules would be in the first stage and the remaining 1/3

would be in the second stage. Once the array has been estimated,

the design can be optimized with respect to other design variables

including flow rates, scaling indexes,recovery, and Beta.

At this point continuing to create a design by hand calculationis

very tedious considering all the variables that must be addressed

by the design. Thus, design software has been developed to aid the

designer in developing a design of an RO system. Some membrane

manufacturers have made available to the public, design software

that is specific for their membranes. Each software package, while

different in presentation, delivers the same result: design of the RO

unit, including array, operating pressure, scaling indices, and prod-

uct and concentrate water qualities.

The software is based on stabilized, nominal performance of the

membrane selected under design conditions. Actual performance

may vary up to +/-15% of nominal, according to the Dow Water

and Process Solutions-FilmTec Technical Manual.' The software

will give warnings when the basic element operating parameters

are exceeded, such as high element recovery or low concentrate

flow. However, the software will not give warnings when the over-

all design is not practical. In fact, the Dow Water and Process Solu-

tions FilmTec TechnicalManual states:

"ROSA [Reverse Osmosis System Analysis] 6 only projects

reverse osmosis and nanofiltration system performance from

a User-controlled set of data input and design decisions. The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-234-2048.jpg)

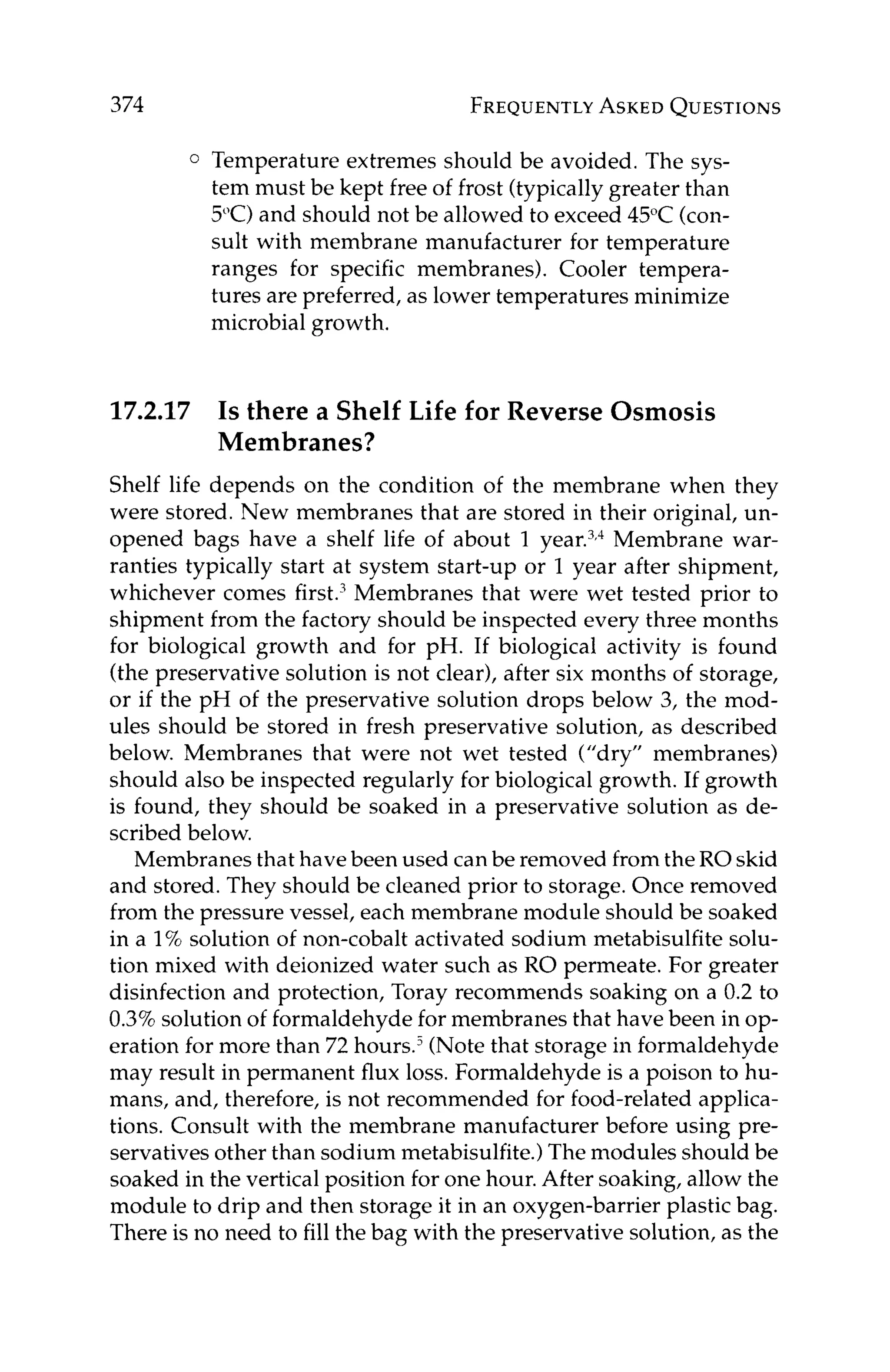

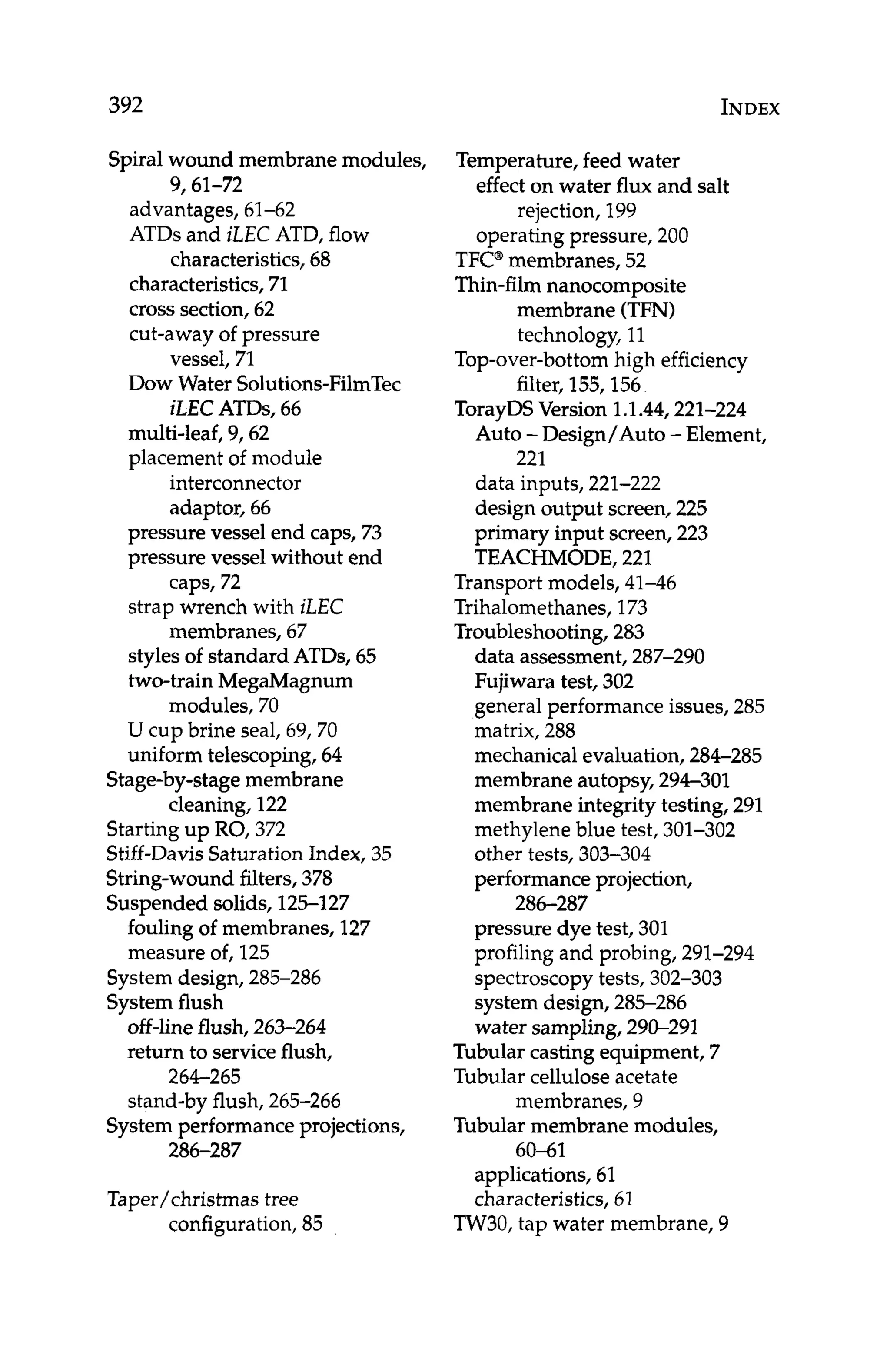

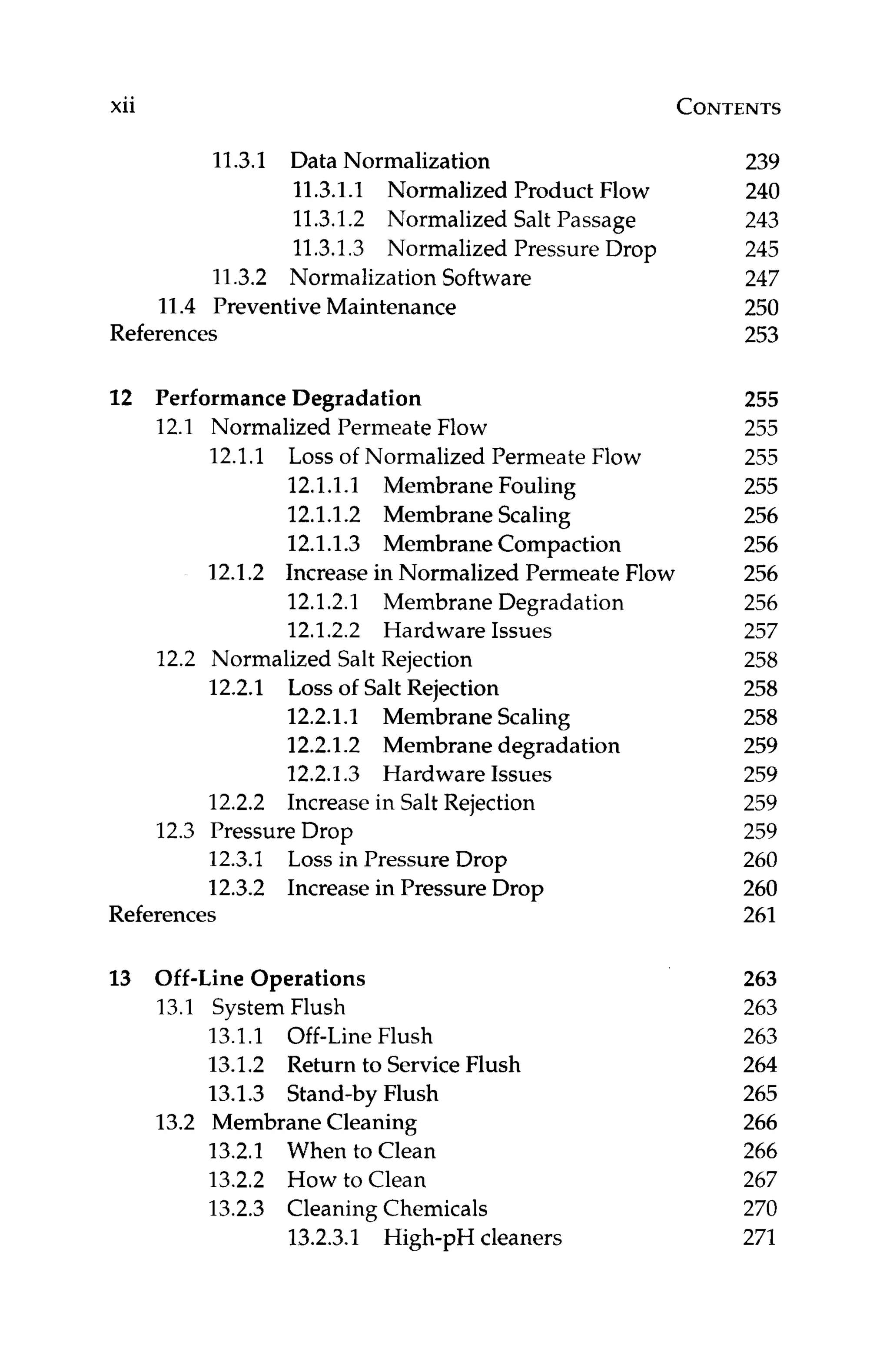

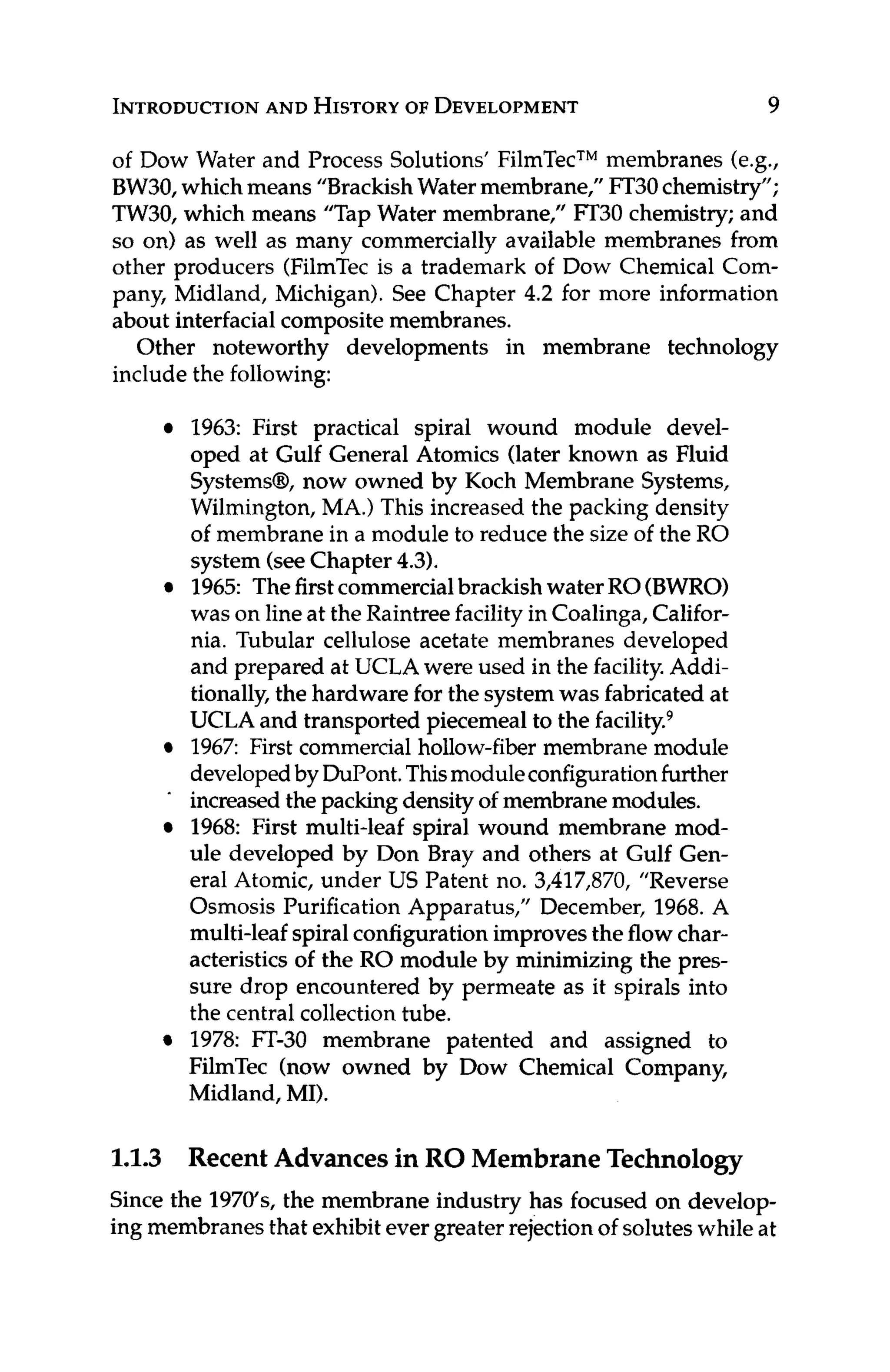

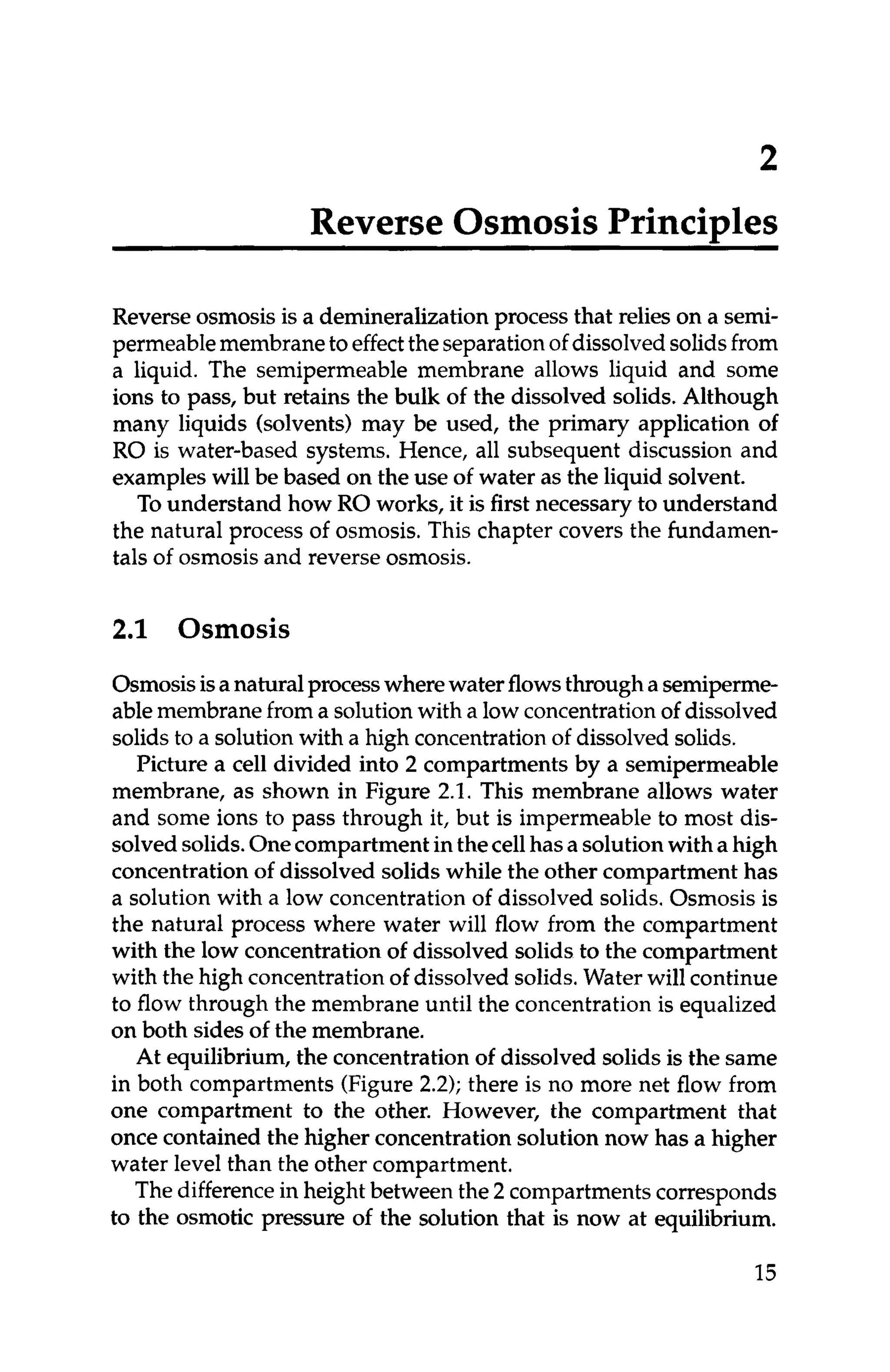

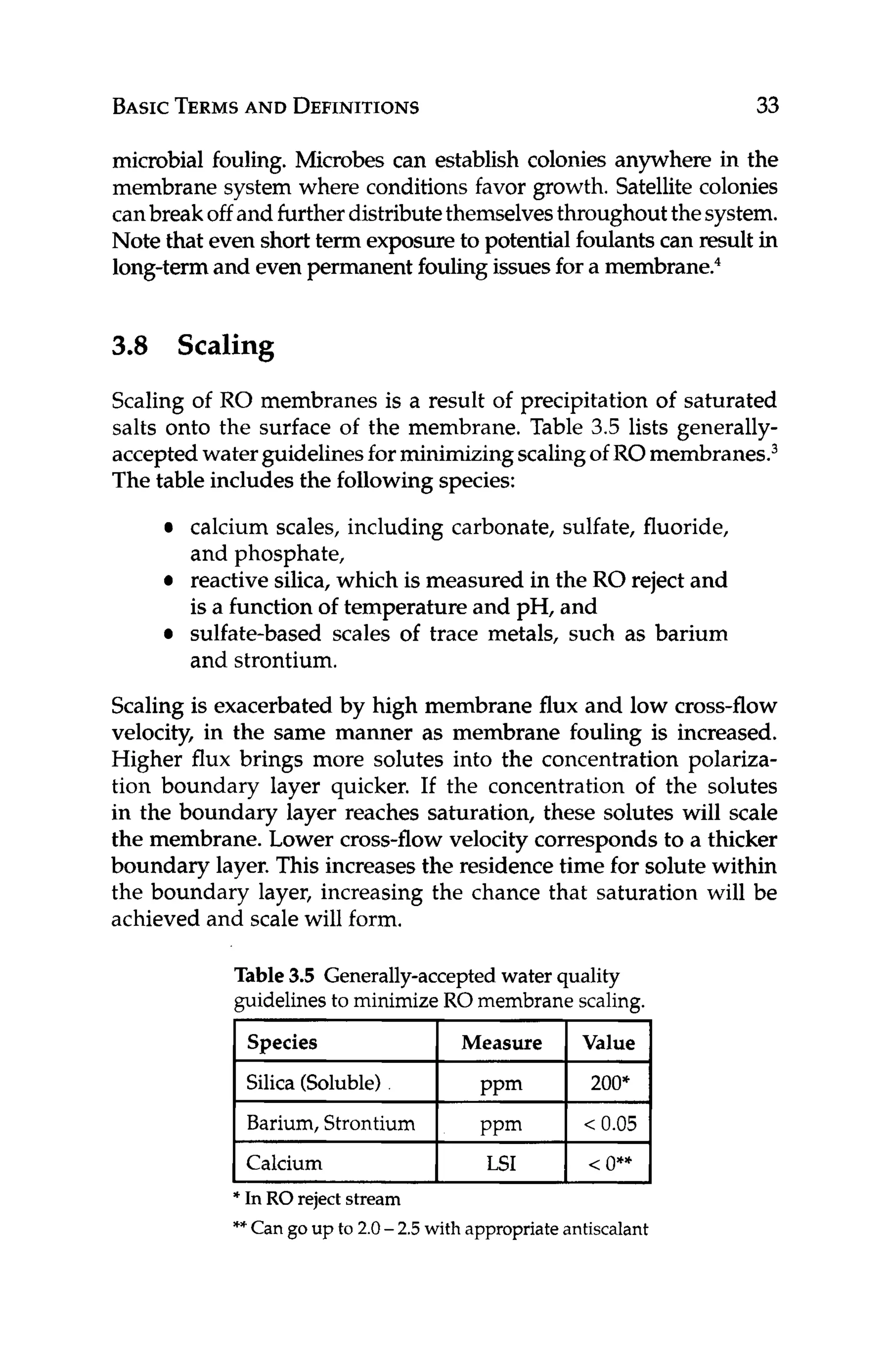

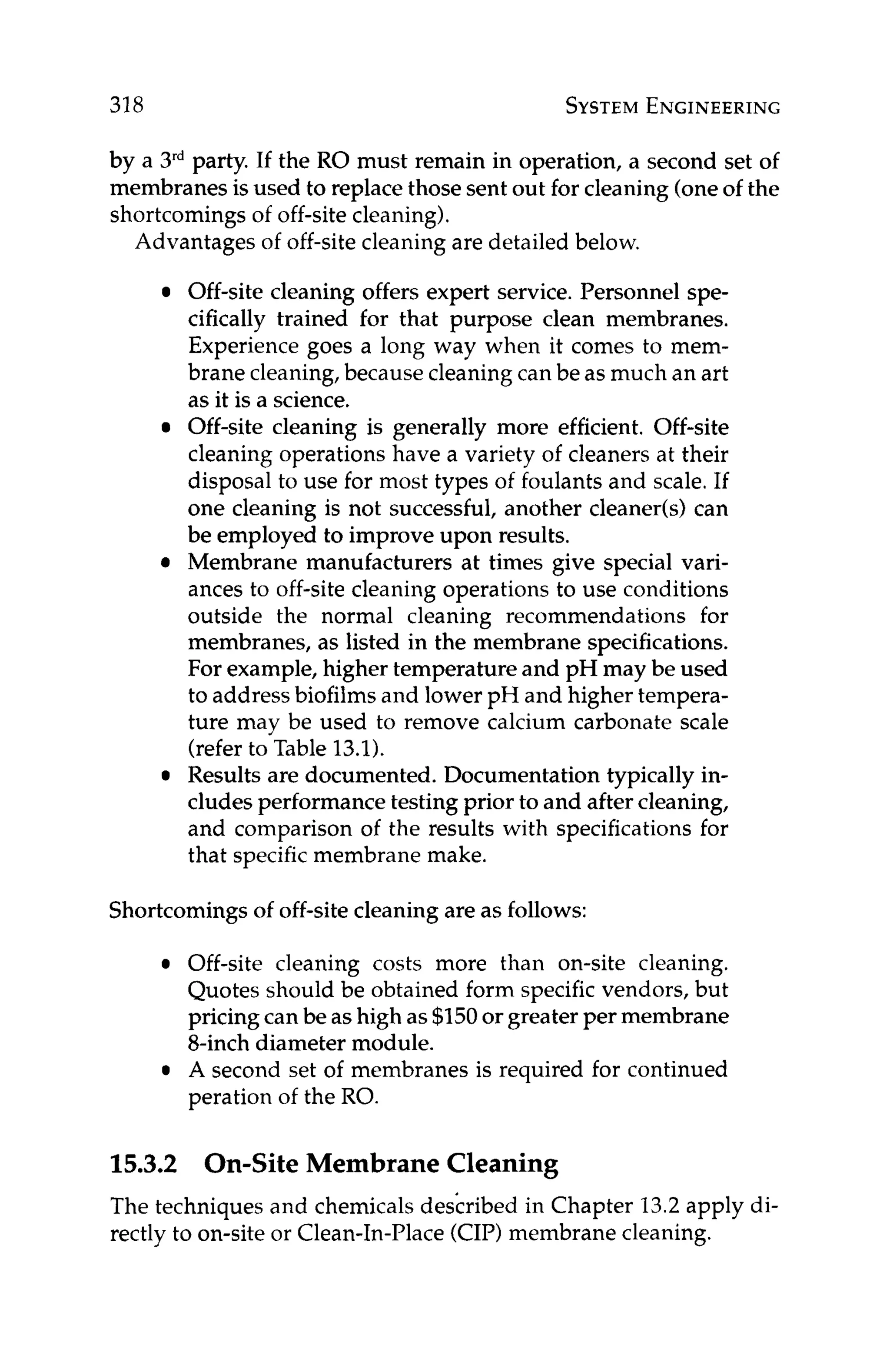

![RO DESIGN

AND DESIGN

SOFTWARE 213

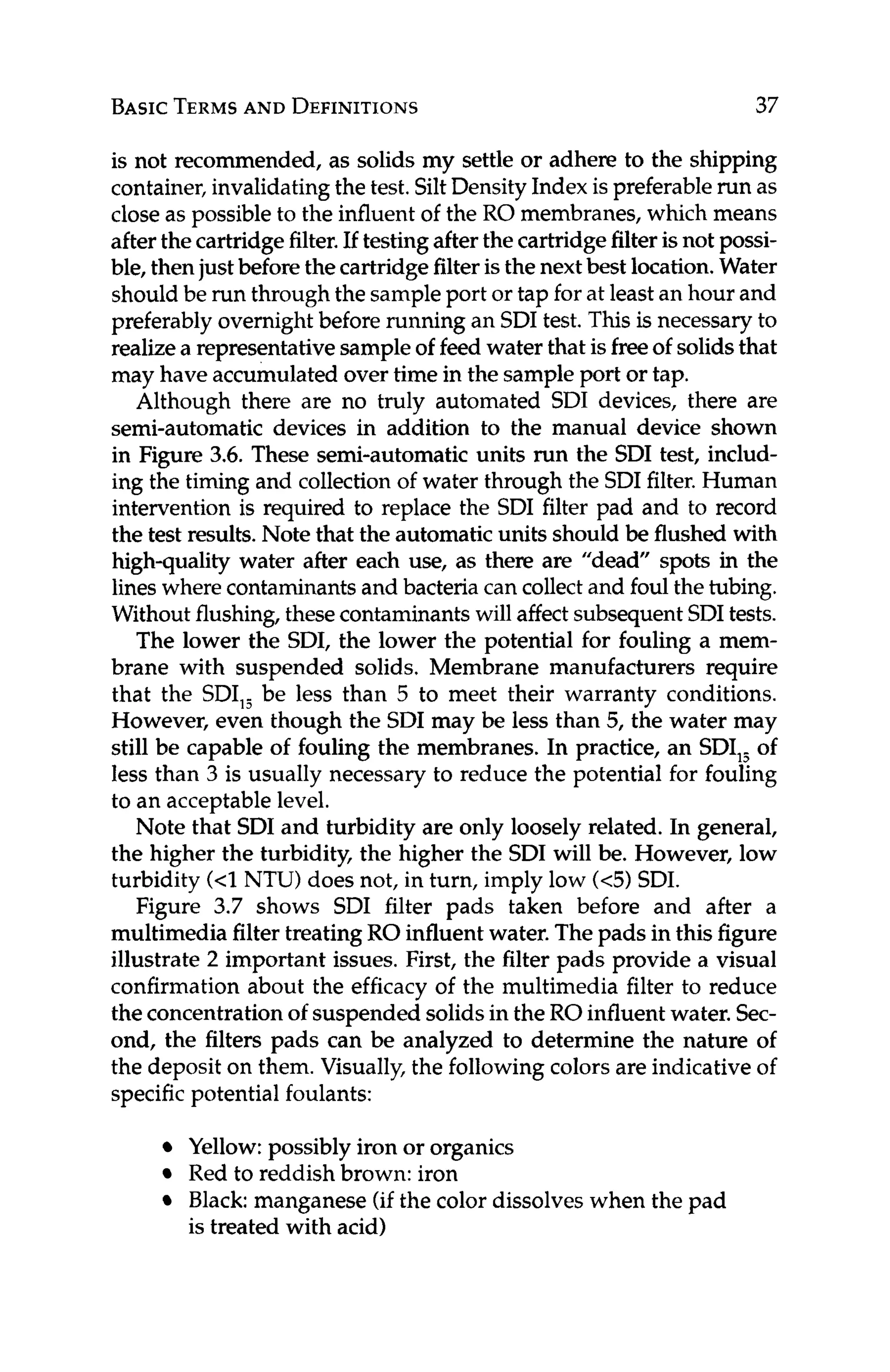

1 Membrane Manufacturer Design Software Package

Dow Water Solutions--FilmTec Reverse Osmosis System Analysis

(Minneapolis,MN) (ROSA)

www.dow.com

program does not judge whether a system design is realistic [em-

phasis added] or optimized for a given set o

f conditions. It is

the Useis responsibility to review and judge the system design

based on the anticipated or existing pretreatment, reasonable

design guidelines, and experience.”’

Toray Membrane, USA

(Poway,CAI

www.toraywater.com

(Oceanside,CA)

www.membranes.com

Koch Membrane Systems

Hydranautics

(Wilmington,MA)

www.kochmembrane.com

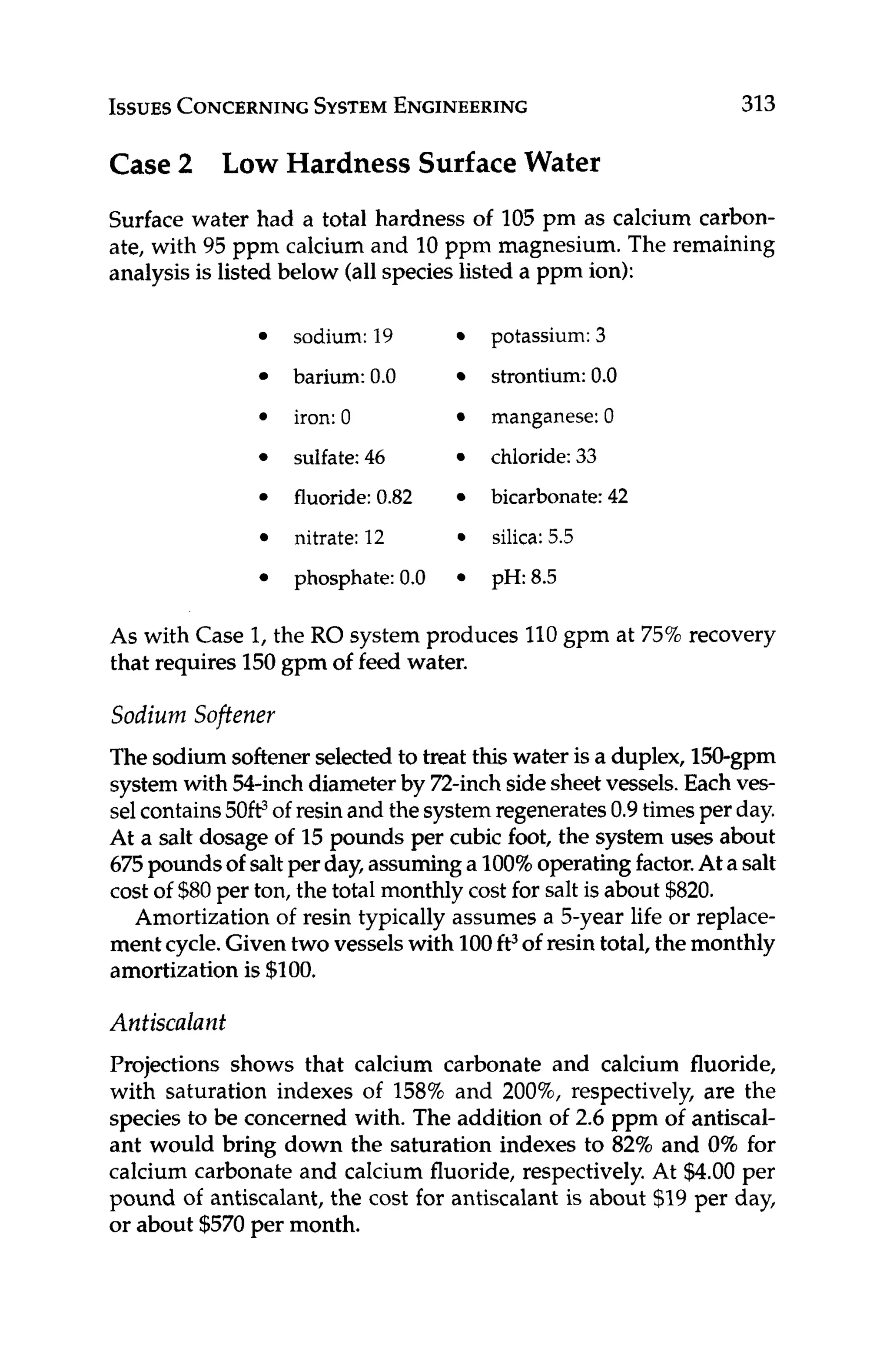

Hence,experienceand common senseare necessary to ensure the

design selected using the any design software package is realistic,

particularly for feed streams other than well water with SDI <3.

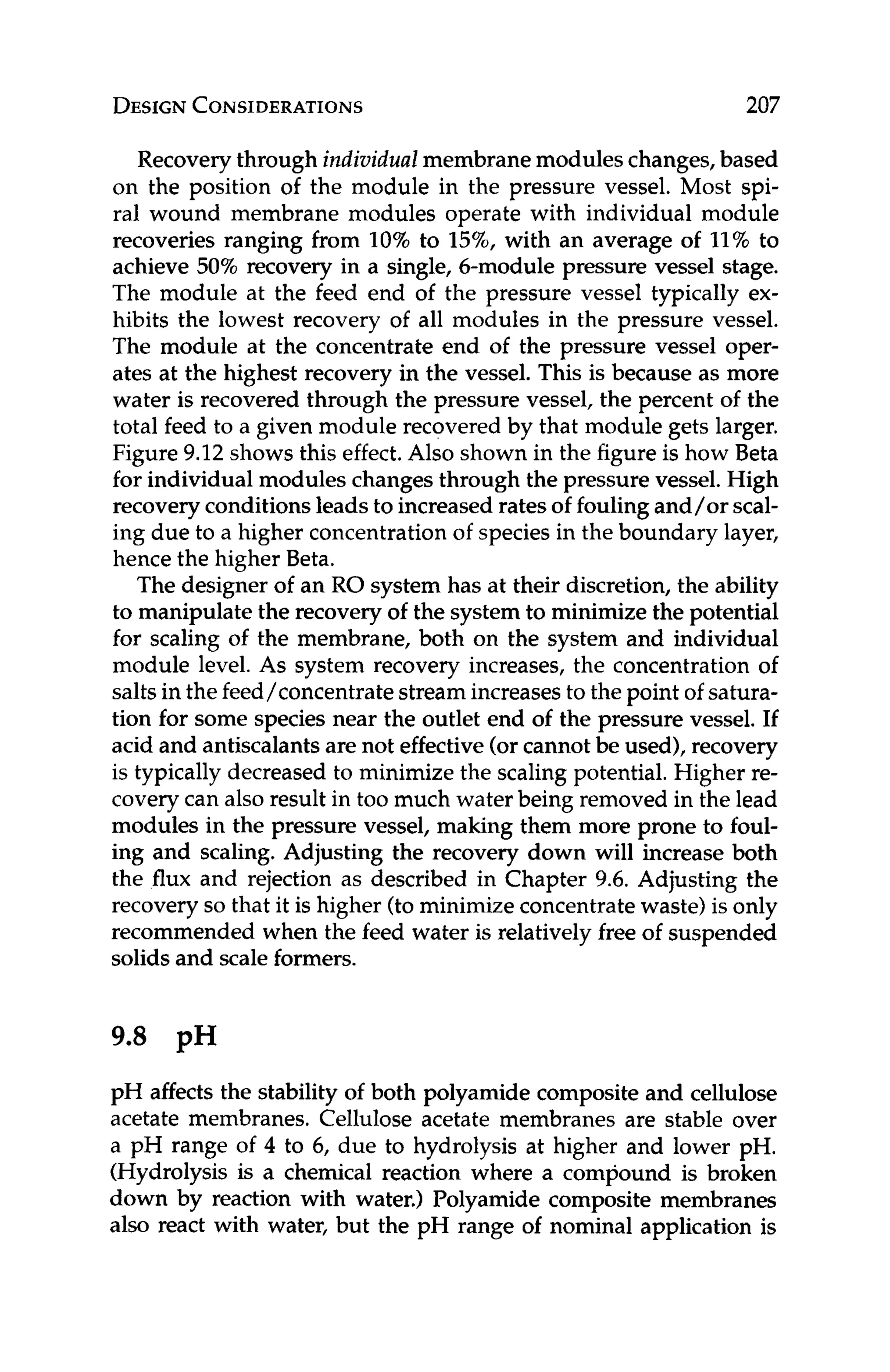

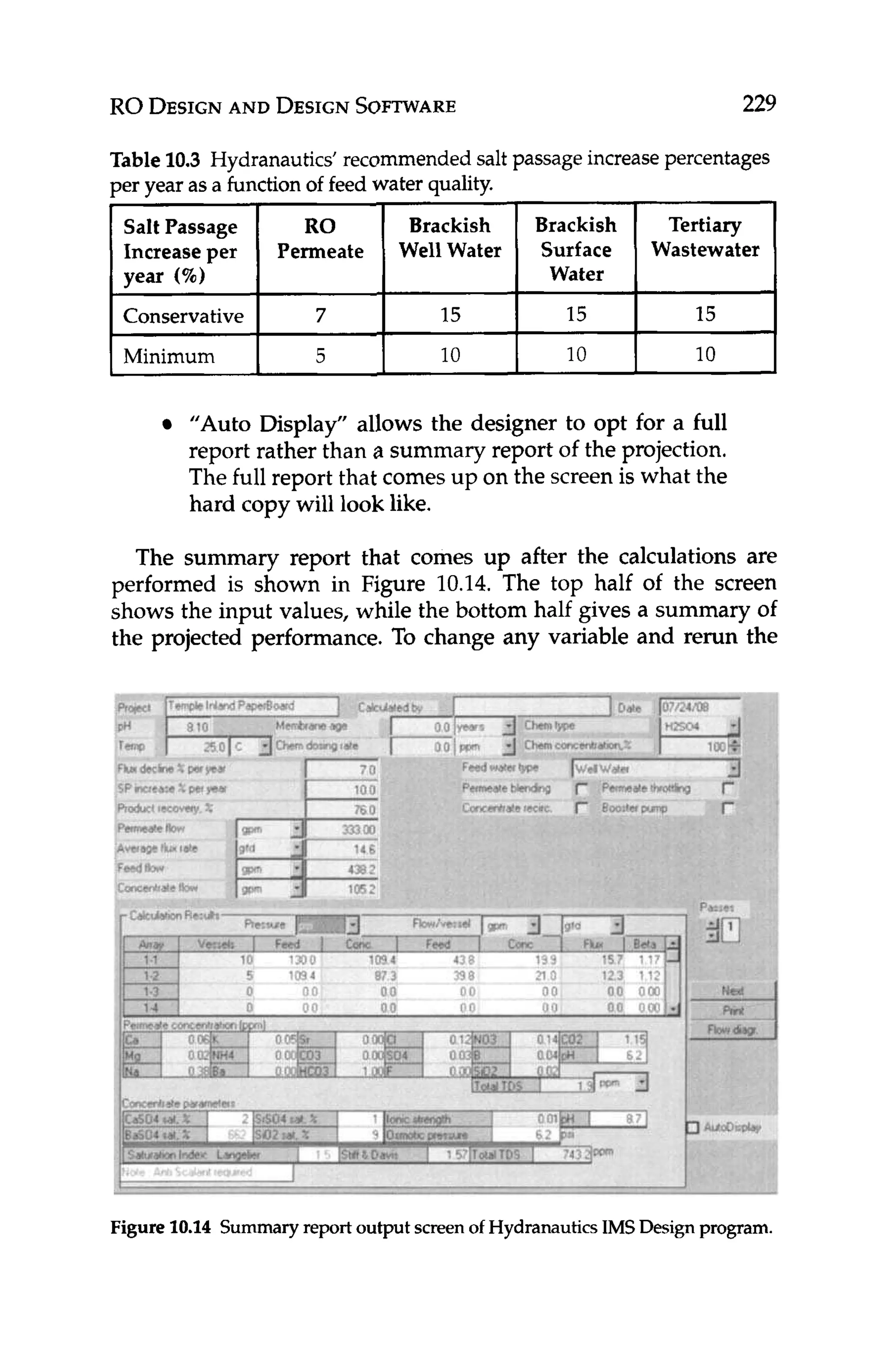

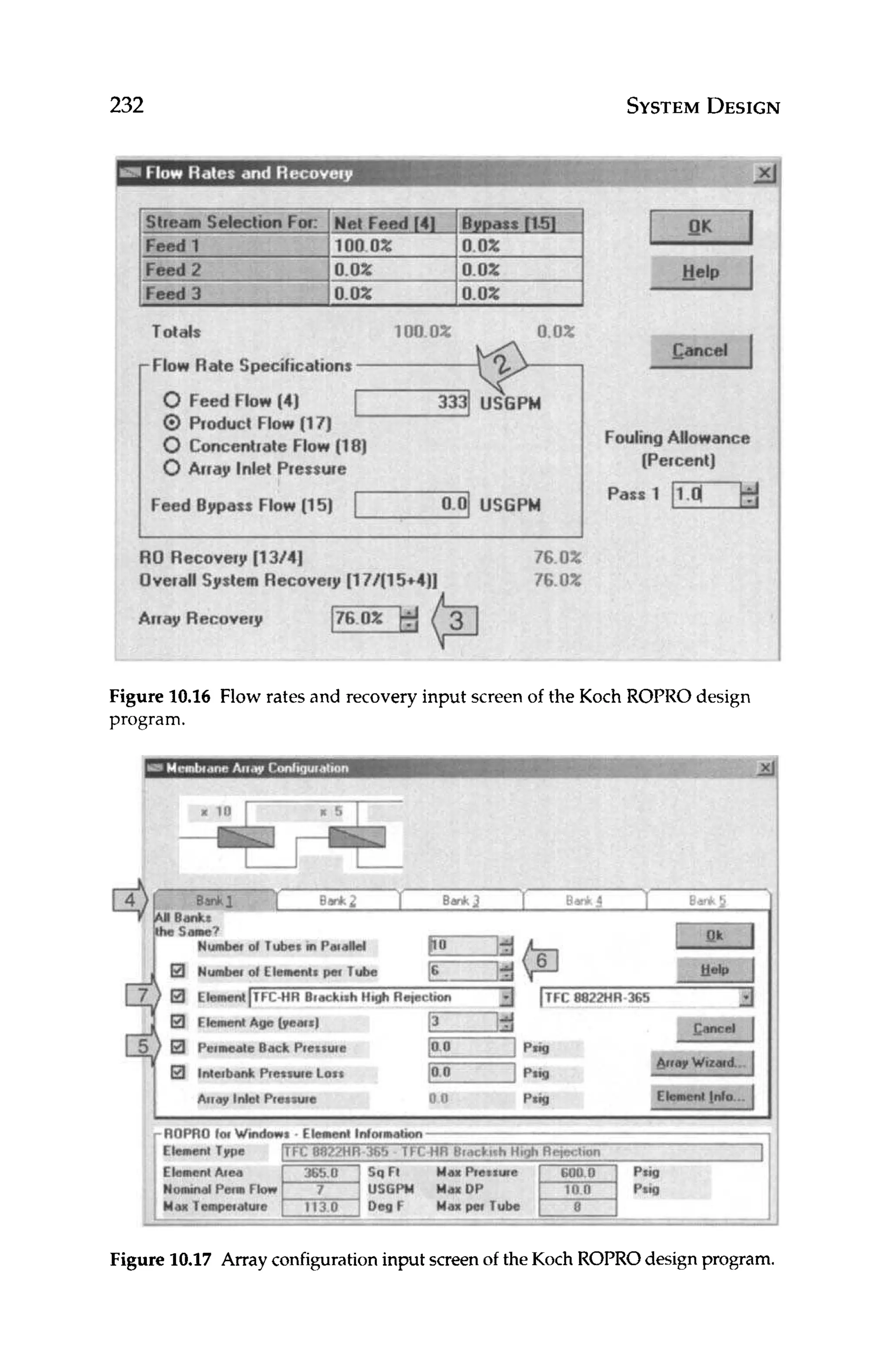

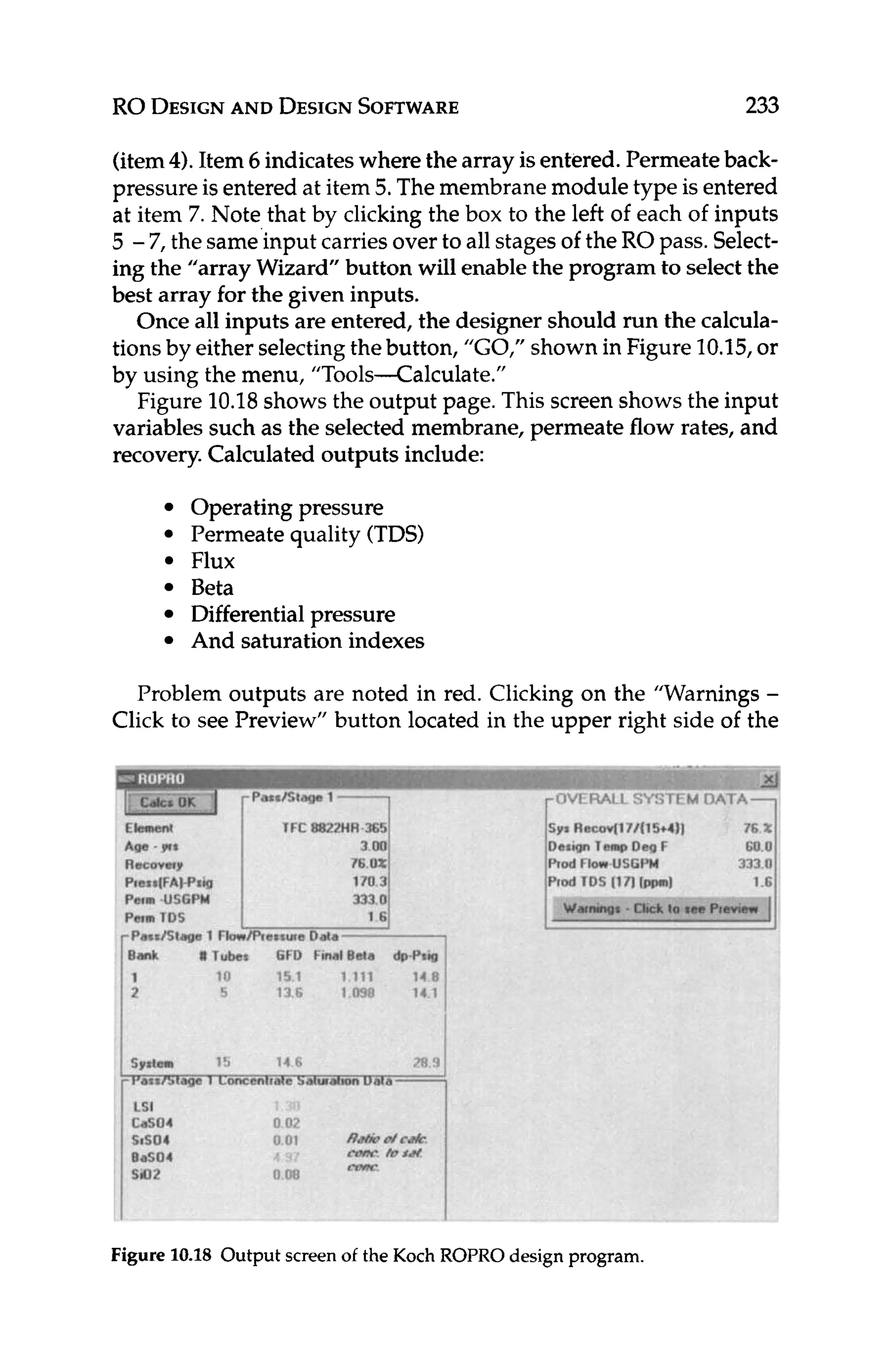

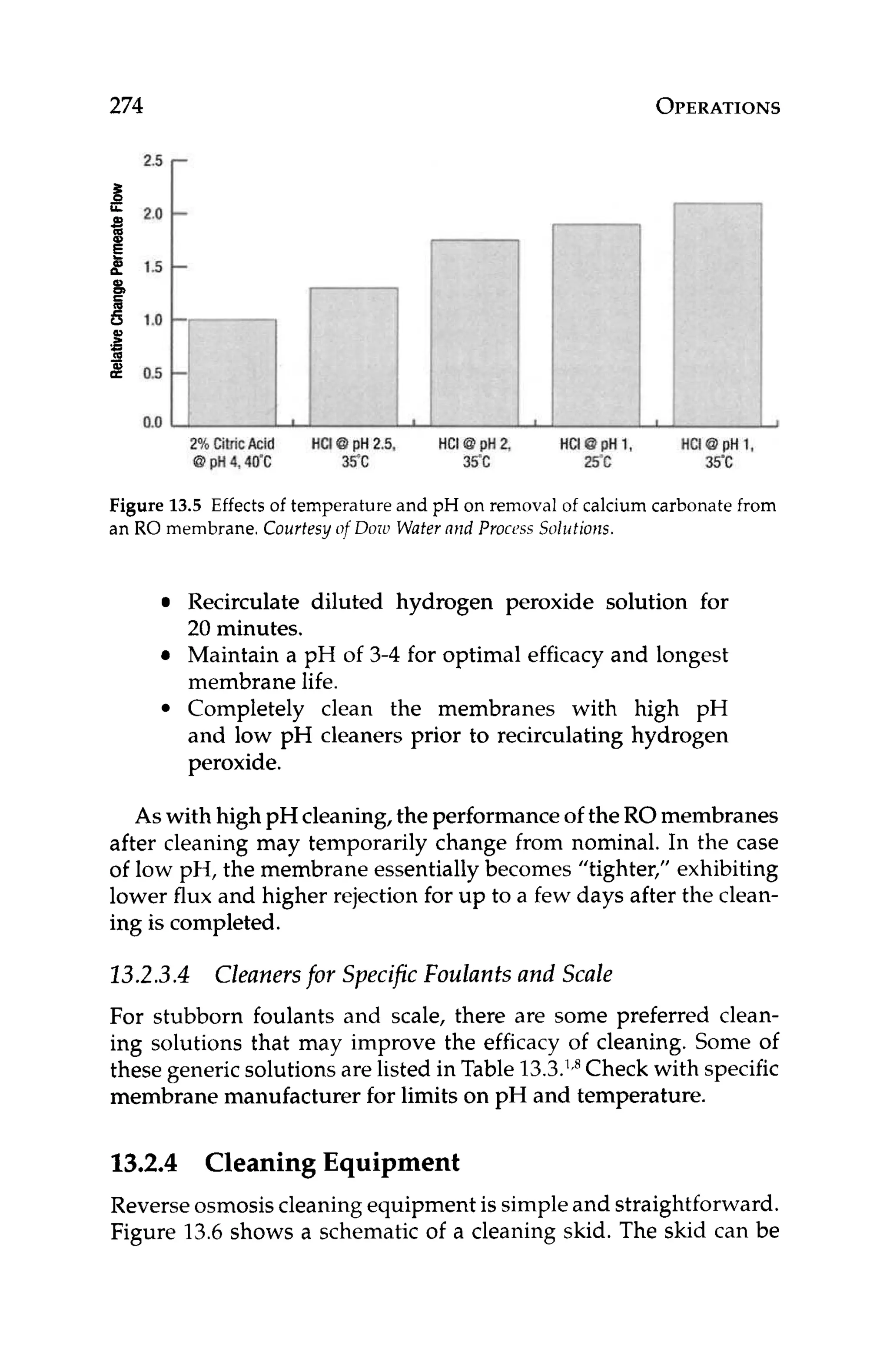

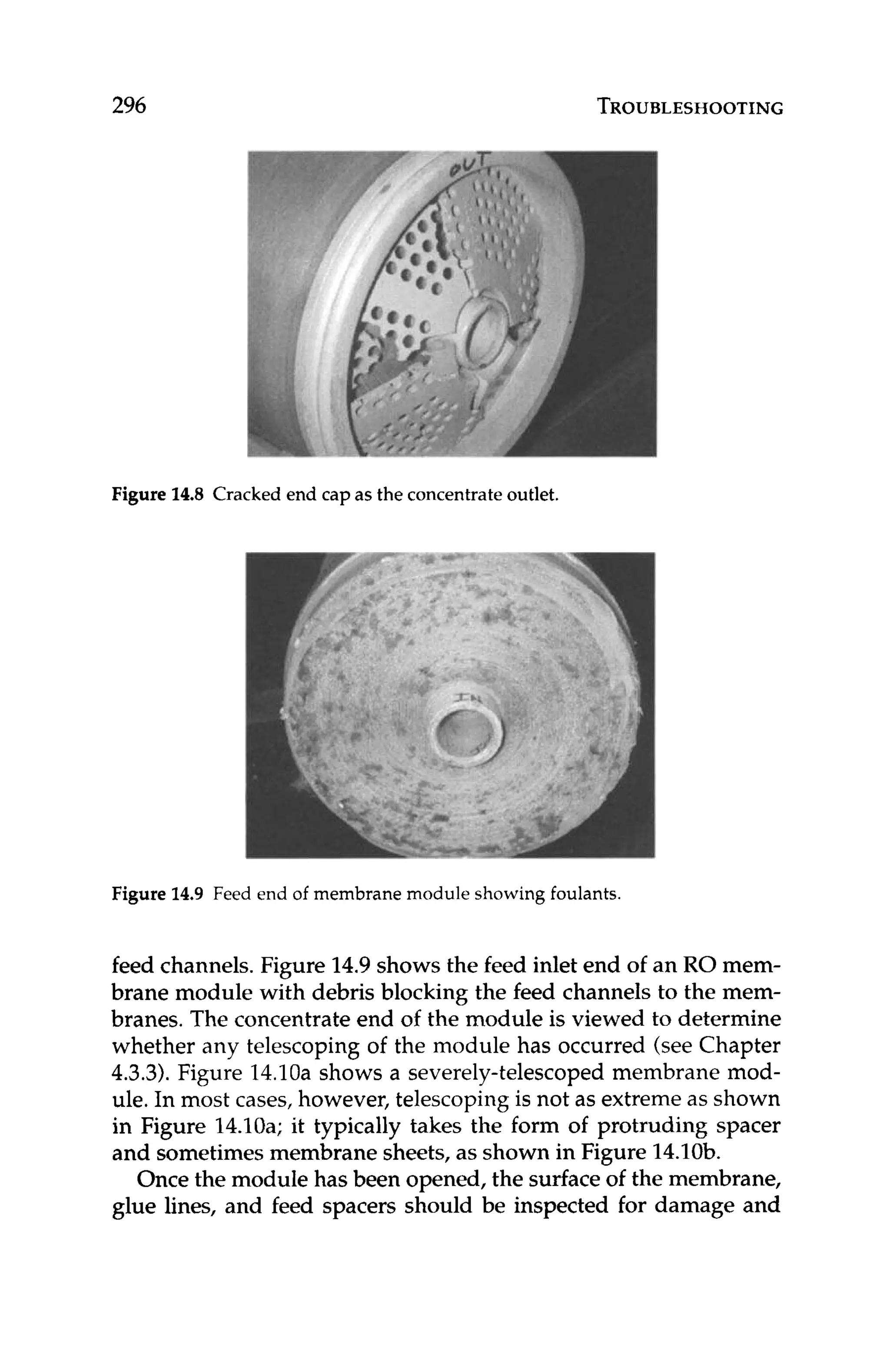

Table 10.1 lists four major US.membrane manufacturers and

their respective design programs that are available to the public.

Each design program is discussed in detail below. The programs

can be downloaded from the manufacturers’ respective websites.

TriSep Corporation, Goleta, California also offers a design pro-

gram that can be downloaded from their website; it is not covered

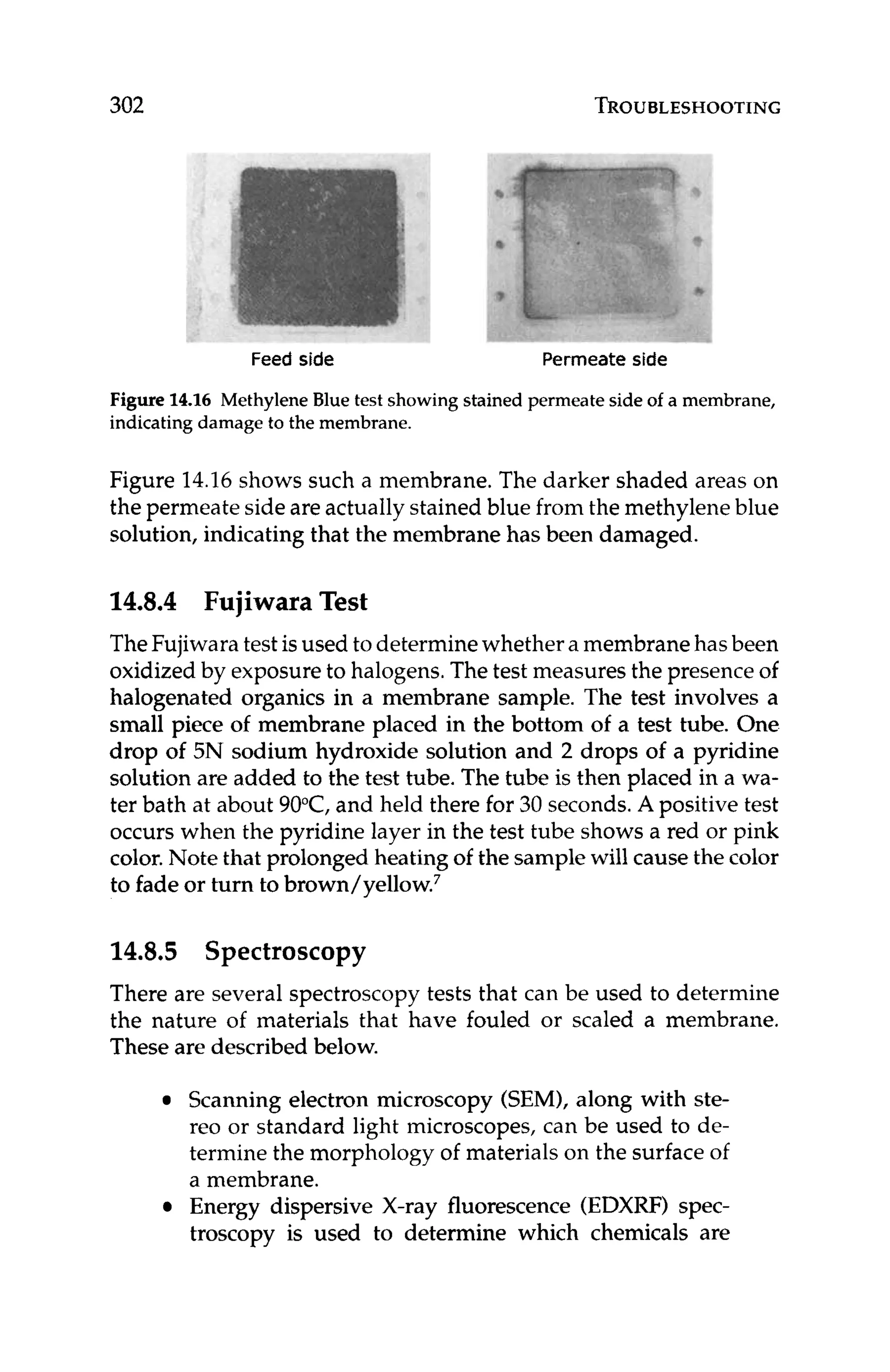

in this chapter as TriSep is not generally considered a major US

manufacturer. The other major U.S. manufacturer, GE Water &

Process Technologies (Trevose,Pennsylvania), does not offer a de-

sign program that is availableto the public. Applied Membraneso,

Inc., (Vista, California),another U.S. manufacturer,does not offer a

design program to the public.

~

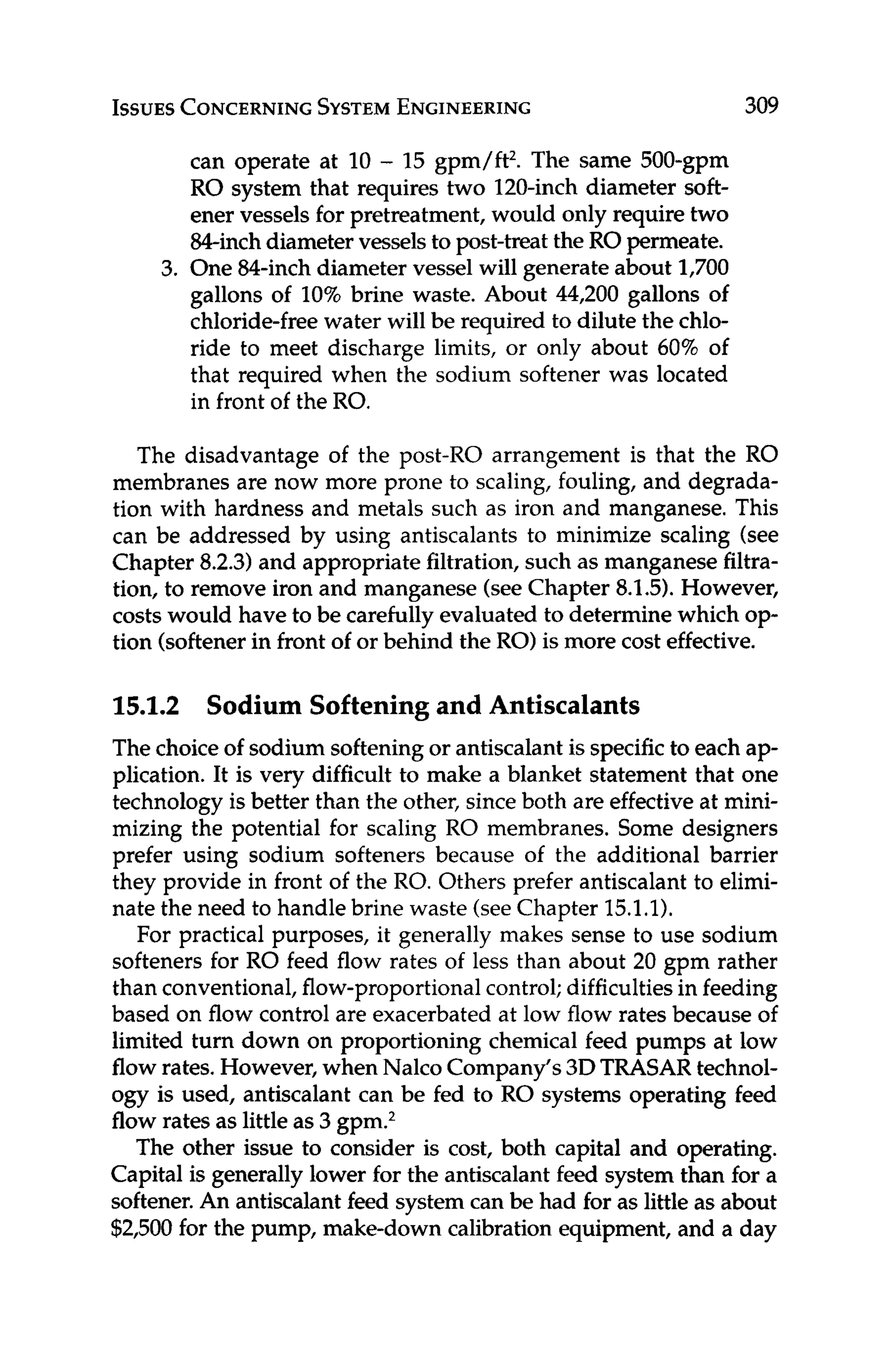

Toray Design System (TorayDS)

Integrated Membrane SolutionsTM

(IMSDesign)

ROPRO@

Table 1

0

.

1 Four major US suppliers of RO membranes and their design

programs Available to the public via download from their respective

websites.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-235-2048.jpg)

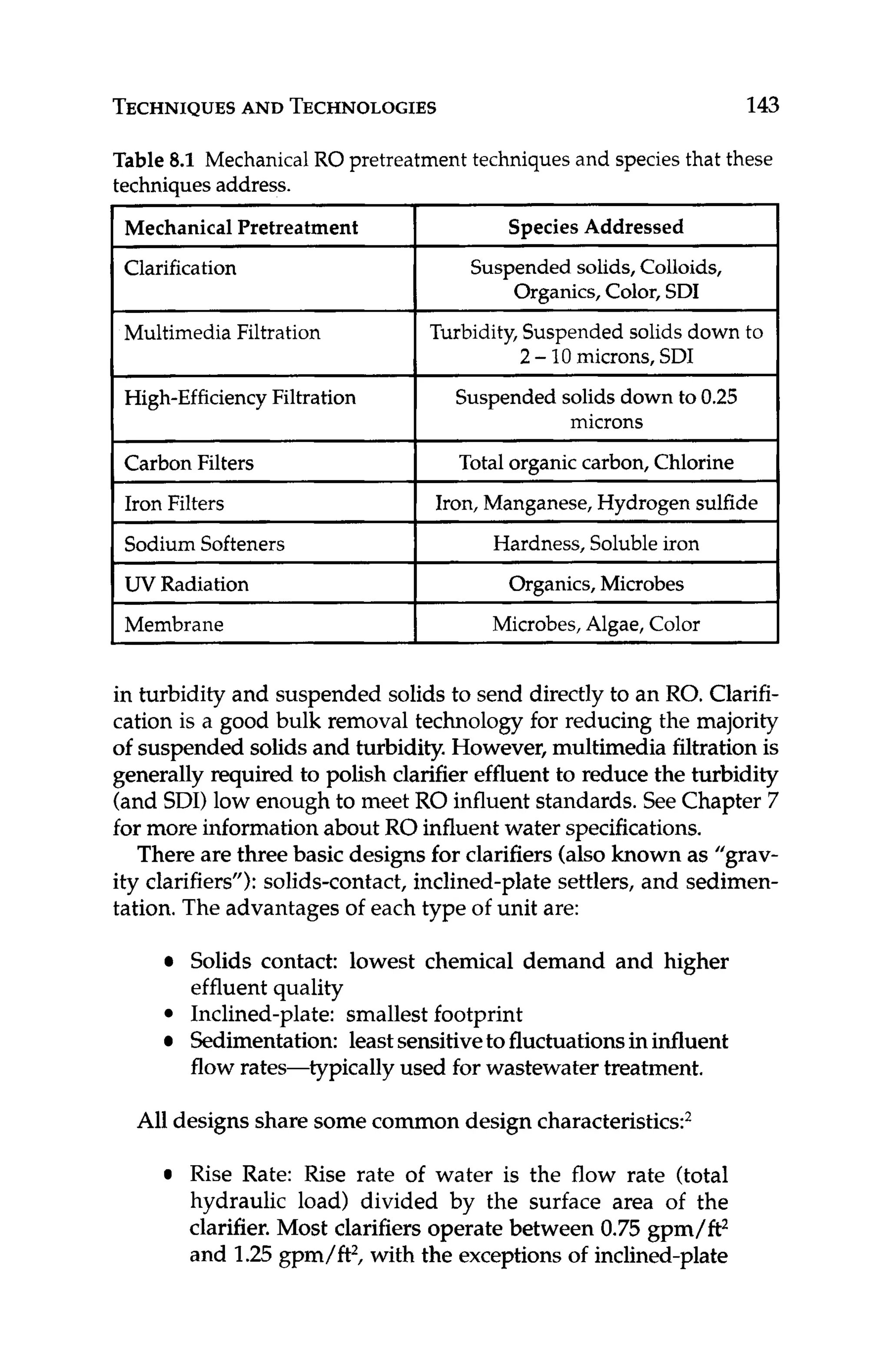

![244 OPERATIONS

and

“s”= subscript for ”standard” conditions

“a” = subscript for ”actual” conditions

Monitoring salt passage is important in tracking membrane seal-

ing and/or degradation. In both of these cases, salt passage will

increase with time. If membrane degradation is occurring, this in-

crease in salt passage is easy to understand. In the case of mem-

brane scaling, however, the increase in salt passage is not so intui-

tive. Consider the followingexample.

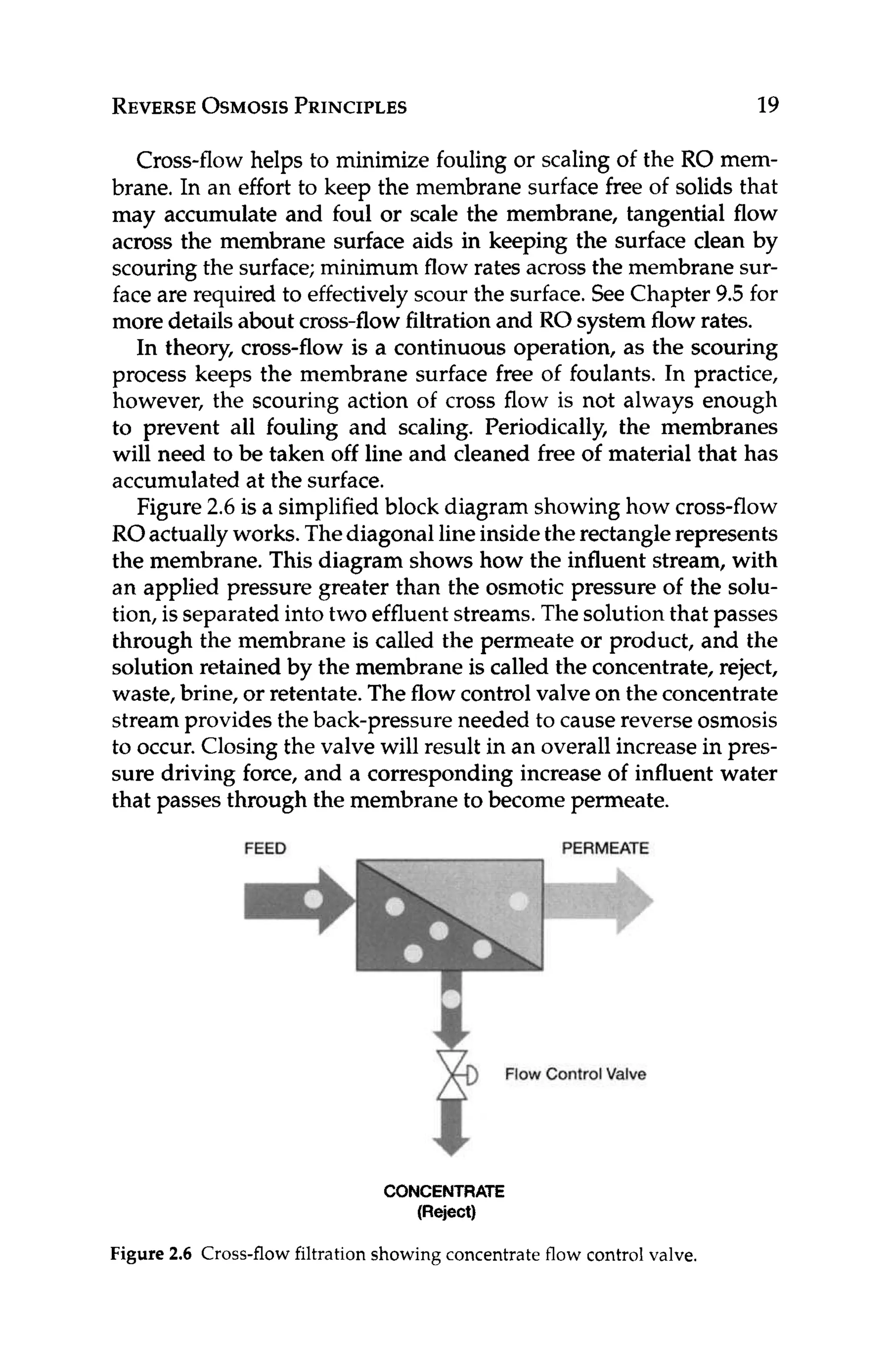

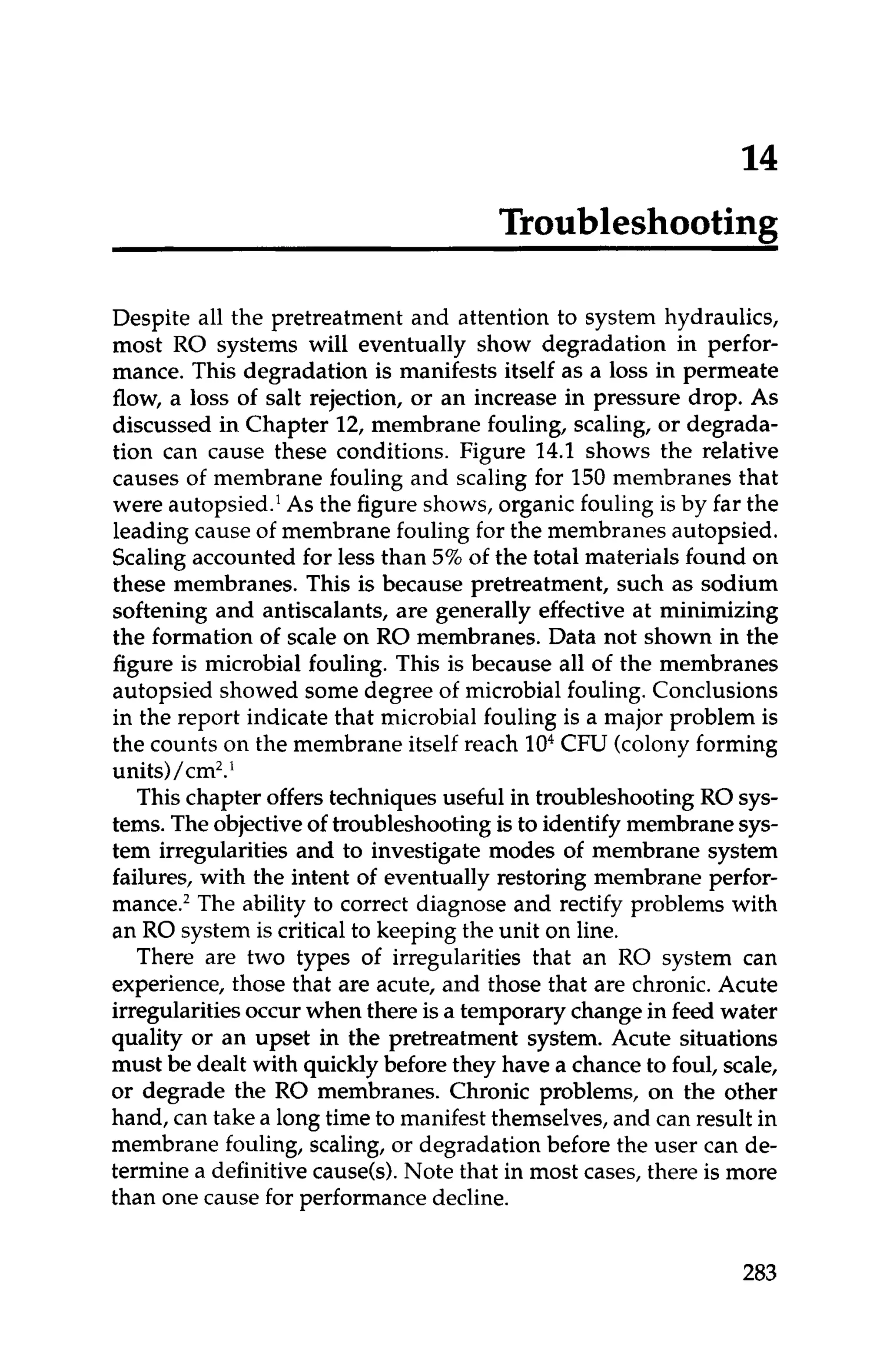

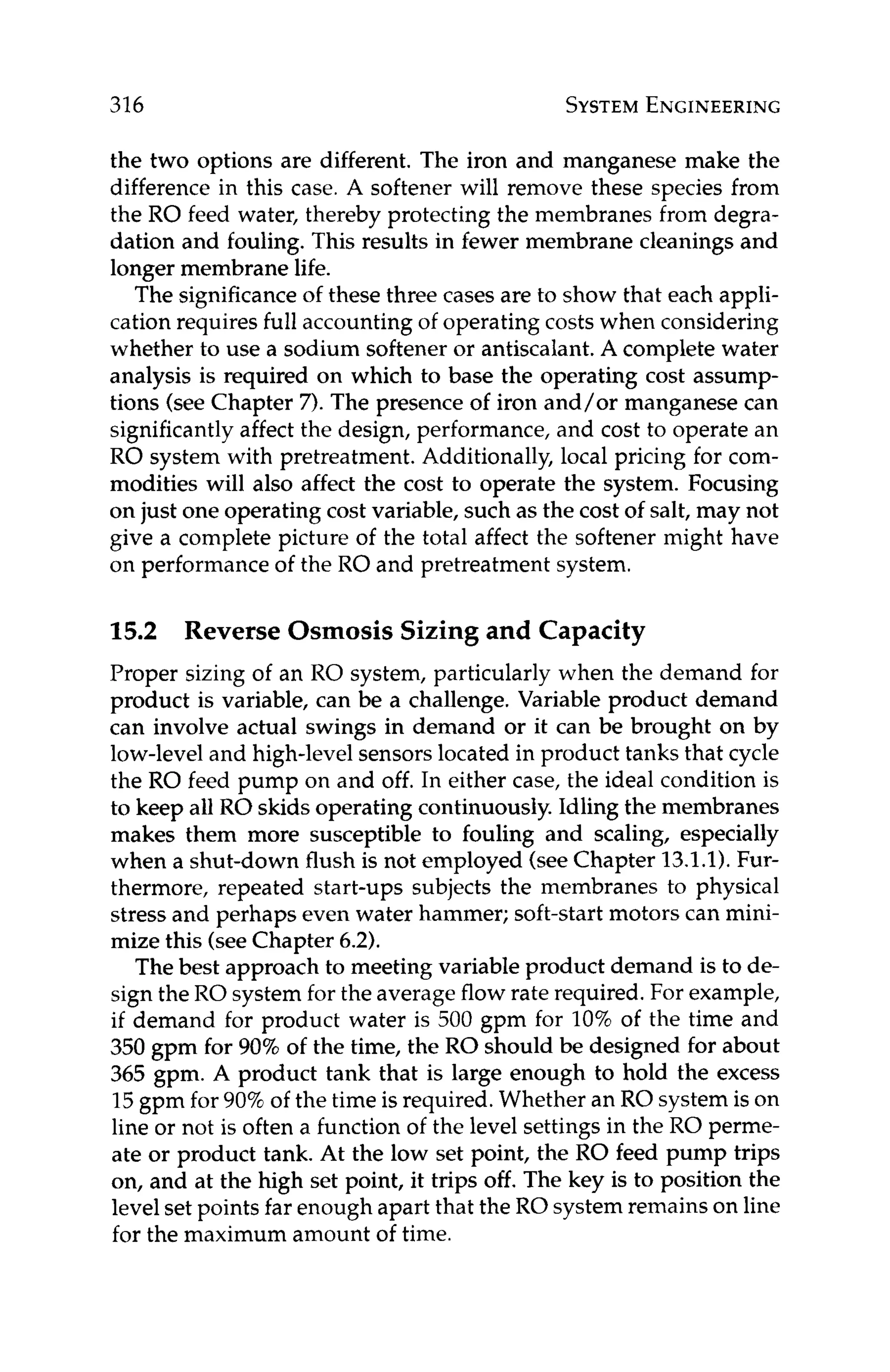

Figure 11.4depicts a cross-sectionof a membrane with a layer of

calcium carbonatescaleon the surface.Theconcentrationof calcium

at the membrane surface, Z , is higher than that in the bulk feed, X,

since the concentration at the surface has reached saturation. The

membrane passes saltsbased on what concentrationis actually next

to the membrane. In this case, the membrane is exposed to a satu-

rated concentration, not the lowerbulk solutionconcentration.Even

though the percent passageof calciumthrough the membranesstays

constant, the scaled membrane will yield higher permeate concen-

tration of calcium.This is because the concentrationof calcium that

the membrane is exposed to at the membrane surfaceis higher than

the bulk solution concentrationof calcium, [Z],[X].

Normalized salt passage is generallynot used as the primary indi-

catorof whentocleanmembranes.Thisisbecausenormalizedproduct

flowand/or differentialpressuredrop (seebelow)will usually indicate

problems with the membranesbefore product qualitybecomes an is-

sue.However, normalizedsalt passage shouldbe used in conjunction

BULK CONCENTRATION“X” 4

Figure 11.4 Cross-section of an RO membrane with a layer of scale on the

surface of the membrane. Concentration of scale formers is higher at the

membrane surface, Z than in the bulk solution, X.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-266-2048.jpg)

![16

Impact of Other Membrane

Technologies

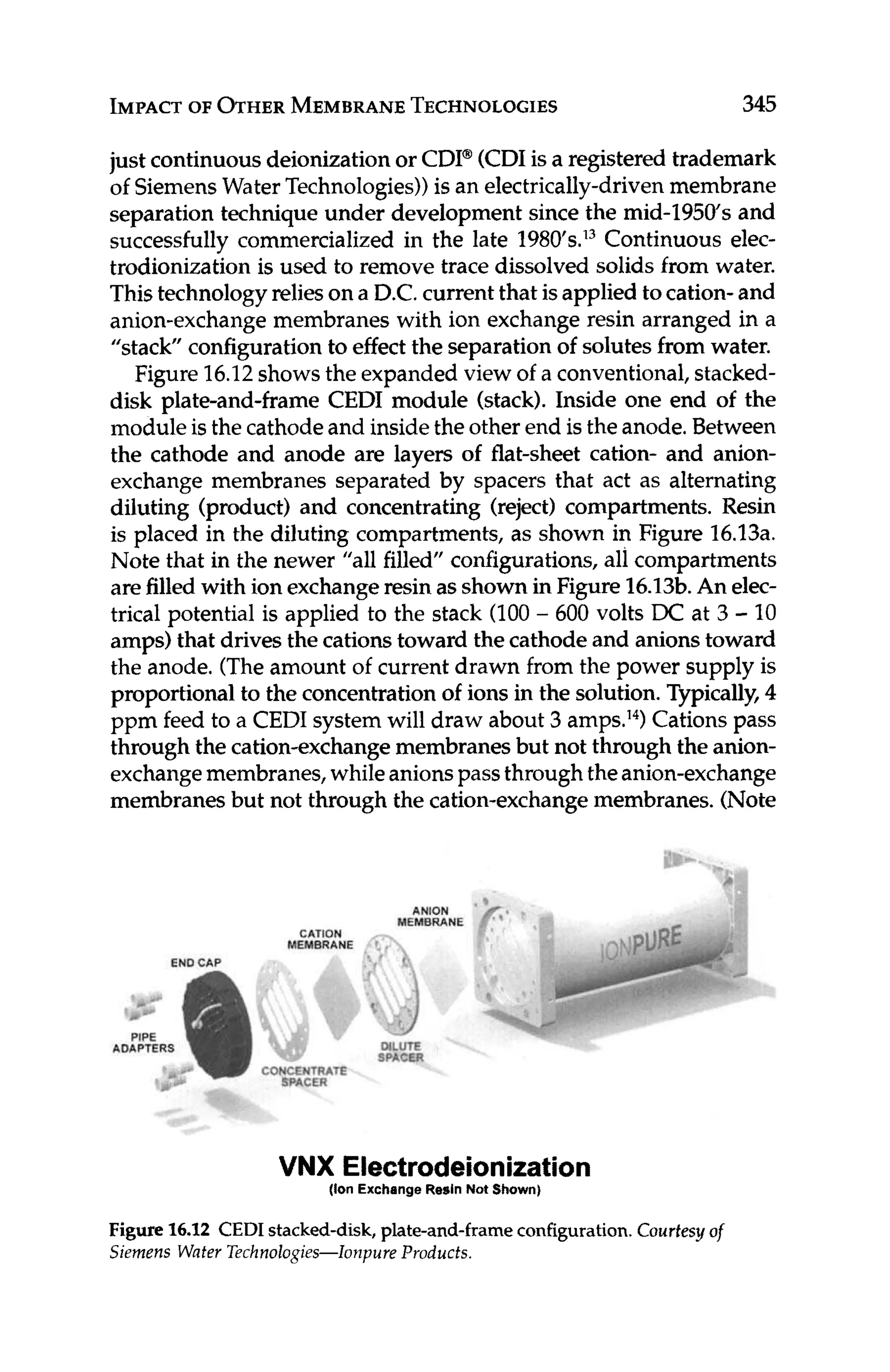

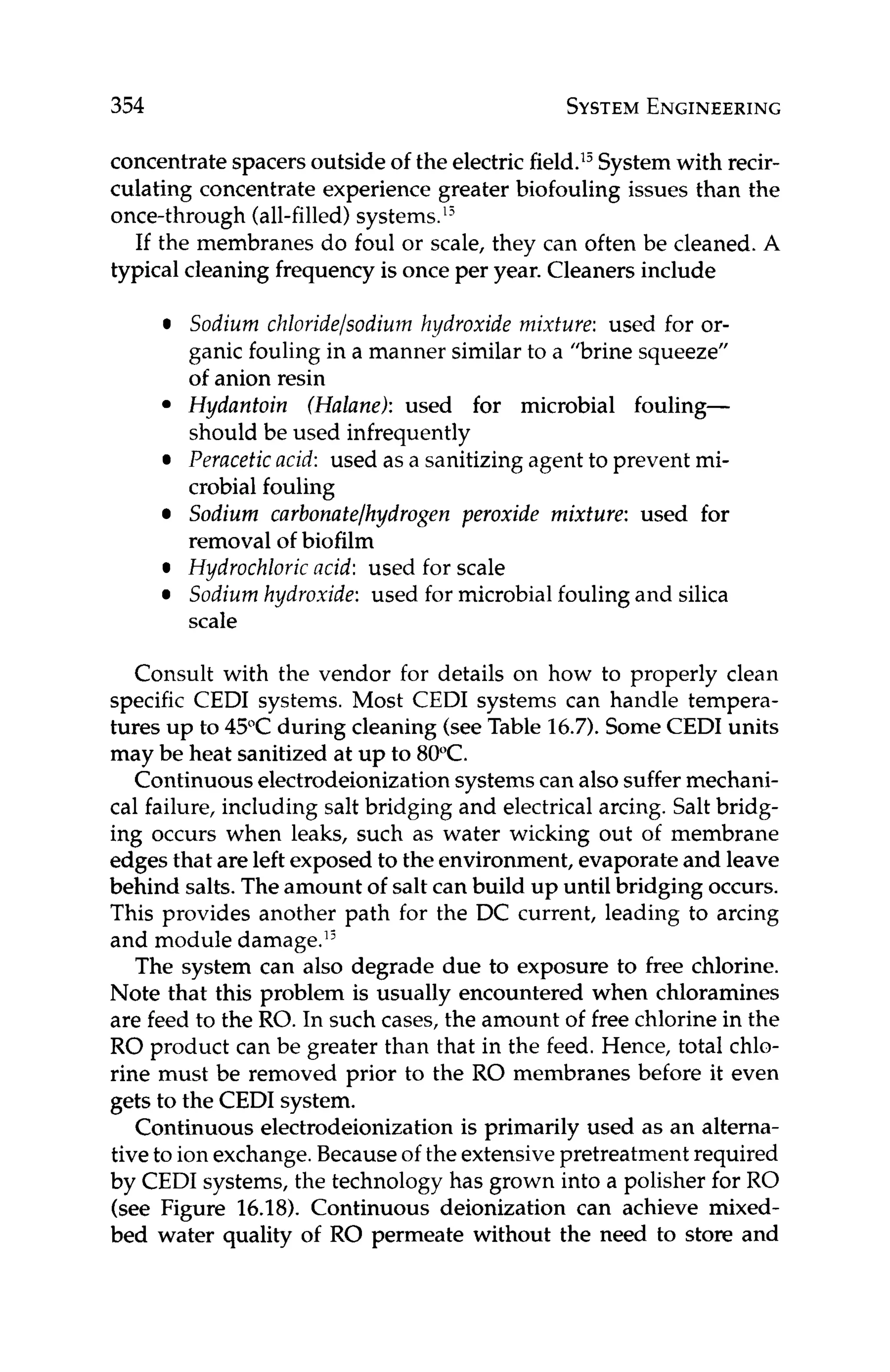

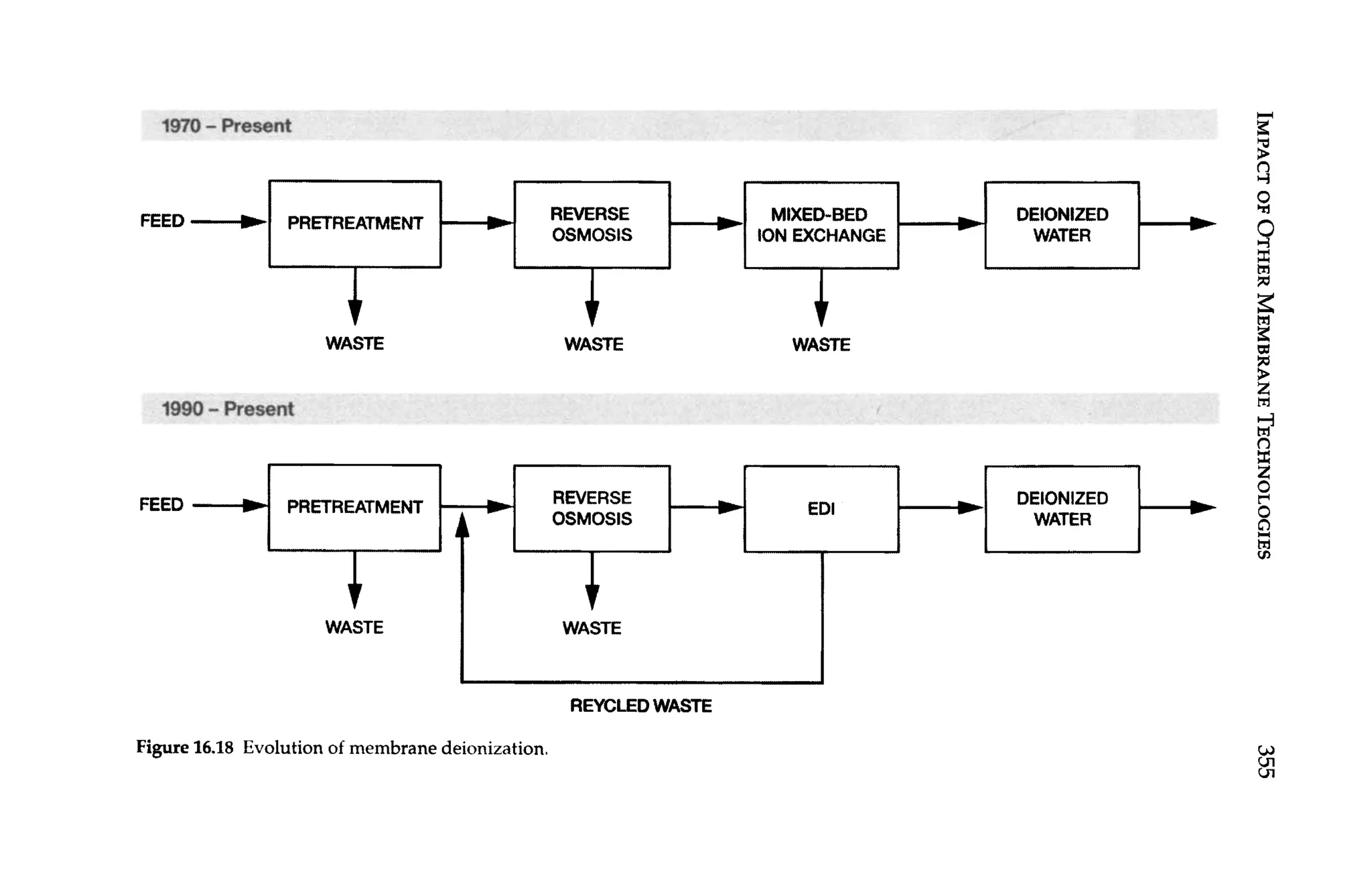

In this chapter, the impact of other membrane technologies on the

operation of RO systems is discussed. Technologies considered in-

clude microfiltration (MF), ultrafiltration (UF), and nanofiltration

(NF) as pretreatment to RO, and continuous electrodeionization

(CEDI) as post-treatment to RO. This chapter also describes the

HEROTM

(high efficiency RO-Debasish Mukhopadhyay patent

holder, 1999) processused to generate high purity water fromwater

that is difficult to treat, such as water containing high concentra-

tions of silica.

16.1 Microfiltration and Ultrafiltration

Microfiltration and UF are pressure-driven membrane separation

technologiesthat use positive pressureor suctionto separateparticles

(and high molecular-weight soluble species in the case of UF) from

solution (seeFigure 1.1).The history of MF and UF membranes goes

back to the early 1900's. Bechhlold developed the first synthetic UF

membranes made from nitrocellulose in 1907.' He is also credited

with coining the term "ultrafilter." By the 1920'sand 1930'sboth MF

and UF nitrocellulose membranes were commercially available for

laboratory use. The first industrial applications of MF and UF came

in the 1960's and 1970's. Microfiltration membranes became viable

for industrial application in the 1970's when Gelman introduced the

pleatedMFcartridge.' Ultrafiltrationmembranesbecomeindustrially

viable in the 1960's when Amicon began preparing UF membranes

using a modified Loeb-Sourirajan method (seeChapter4.2.1).]

Microporous membranes are used to effectthe separationby MF

and UF processes. These microporous membranes differ from poly-

amide composite RO membranes in that they are not compositesof

two differentpolymeric materials; they are usually constructedusing

a singlemembrane polymeric material.In simpleterms, both UFand

MFtechnologiesrelyon sizeastheprimaryfactordeterminingwhich

325](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/reverseosmosispdf-230430025016-321d174f/75/Reverse_Osmosis_pdf-pdf-347-2048.jpg)