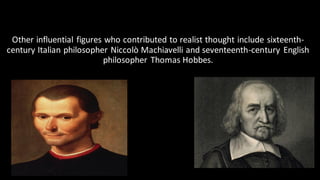

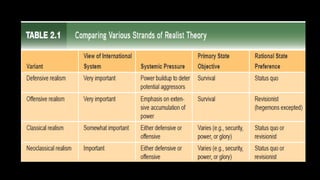

The document presents an overview of realism as a school of thought in international relations, tracing its historical roots from ancient Greece to modern perspectives. Realism posits that states are the central actors in a self-help system driven by power dynamics, where moral considerations are often secondary to national interests. Different branches of realism, including classical, structural, and offensive realism, highlight various aspects of state behavior, yet the theory faces criticism for its lack of clarity and inability to account for new developments in global politics.