Protein Microarray For Disease Analysis Methods And Protocols 1st Edition Tanya Knickerbocker

Protein Microarray For Disease Analysis Methods And Protocols 1st Edition Tanya Knickerbocker

Protein Microarray For Disease Analysis Methods And Protocols 1st Edition Tanya Knickerbocker

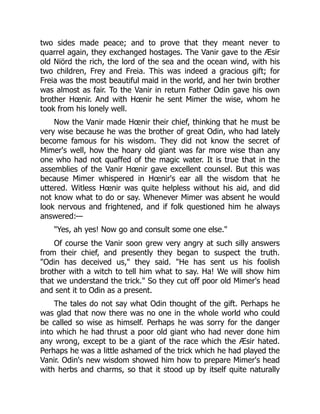

![7

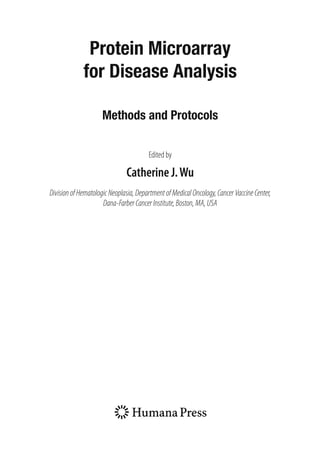

Detecting and Quantifying Multiple Proteins

Cytokines acting on the same cell often exhibit

synergistic or

antagonistic effects (16), but IL-12, Ang, and VCAM-1 are, to a

first approximation, independent. We also found in this study that

molecular markers are not uniformly prognostic, but instead vary

in their value depending on a combination of clinical variables

(age, diastolic blood pressure, serum albumin, and method of vas-

cular access) (9). This may explain why previous reports aiming to

Outcome

Ang

EGF

Fet-A

ICAM

IL-12

IL-1α

IL-8

MIP-1β

RANTES

TNF-β

TNFR2

TNFR1

VCAM-1

VEGF

d

a

c

b

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 3.5 4.0

Ang

EGF

Fet-A

ICAM

IL-12

IL-1α

IL-8

MIP-1β

RANTES

TNFβ

TNFR2

TNFR1

VCAM-1

VEGF

Log

10

{

fluorescence

}

Log10 { [cytokine] (pg/mL) }

200 500 1000 2000

−4

−2

0

2

[Ang] (pg/ml)

log-odds

of

death

100 1000 10000

−2

0

2

[VCAM-1] (pg/ml)

log-odds

of

death

1 10 50

−2

−1

0

1

[IL-12] (pg/ml)

log-odds

of

death

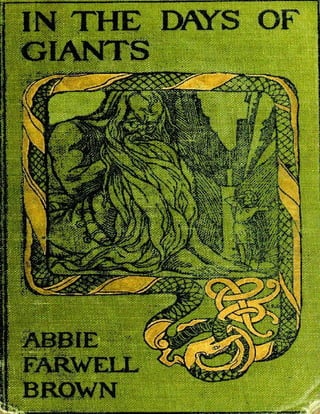

Fig. 2. Serum cytokine levels measured using antibody microarrays. (a) 14 anticytokine capture antibodies were spotted

in quintuplicate in each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. Serum samples were applied to each well in columns 1–11 and

twofold serial dilutions of a mixture of the 14 cognate cytokines were applied to the wells in column 12. (b) Standard

curves generated from the purified cytokines in column 12 of the microtiter plate. (c) Serum cytokine levels of 468

patients initiating hemodialysis. For visualization only, each cytokine was normalized relative to its mean over all the

samples and the patients were ordered according to the first principle component of the cytokine profiles. The outcome

of each patient is shown at the top (red died with 15 weeks of initiating dialysis; black survived more than 15 weeks).

(d) Model built using the cytokine levels that represent the best three-variable model.The solid red lines are the mean of

100 bootstrap samples and the dashed black lines show the variance.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1054127-250526164042-b625bca5/85/Protein-Microarray-For-Disease-Analysis-Methods-And-Protocols-1st-Edition-Tanya-Knickerbocker-26-320.jpg)

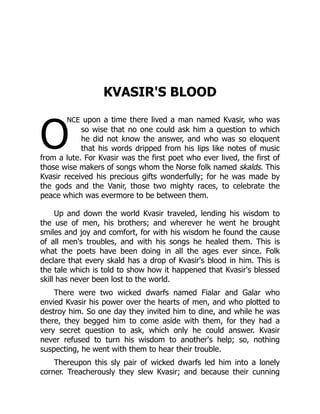

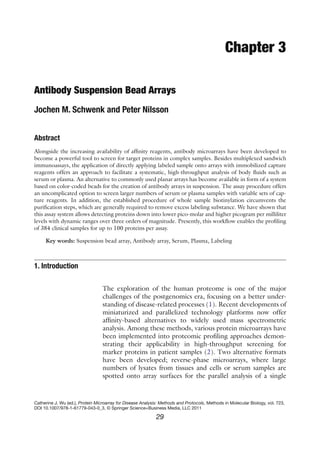

![32 Schwenk and Nilsson

2. Stop solution (4×): 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution, to

store at +4°C. Dilute 1:4 in PBS prior to usage.

3. Detection solution: R-Phycoerythrin modified streptavidin

(Invitrogen) diluted to 0.5 mg/ml in PBST directly before

use and protected from light.

In the following, a method for antibody coupling is described, for

which magnetic and nonmagnetic beads can be utilized. The

main difference between these two bead types is the handling of

the beads during an exchange of surrounding liquid solution. For

coupling quantities not exceeding the amount of positions found

in bench top microcentrifuges, we suggest using microcentrifuge

tubes or tubes with filter inserts to pellet the beads via centrifuga-

tion, while magnetic beads can additionally be manipulated by

magnetic forces without centrifugation. For more than 24 cou-

plings in parallel, microtiter plate based protocols are preferred.

Hereby, proteins can be immobilized on nonmagnetic beads in

filter bottomed microtiter plates (Millipore) with a filter pore

sizes below bead diameter and vacuum devices (Millipore) accom-

modate these plates to remove liquid. For magnetic bead cou-

pling in plates, dedicated plate magnets are available (LifeSept,

Dexter Magnetic Technologies) to facilitate bead sedimentation

and fixation.

1. Prepare antibodies at the desired concentration (e.g., 3 mg or

a solution with antibody concentration of 30 mg/ml per

1×106

beads) in coupling buffer (see Note 2).

3.

Methods

3.1.

Bead Coupling

1

10

100

1000

10000

MFI

[AU]

Antibodies

A

b

-

6

5

A

b

-

6

0

A

b

-

5

5

A

b

-

5

0

A

b

-

4

5

A

b

-

4

0

A

b

-

3

5

A

b

-

3

0

A

b

-

2

5

A

b

-

2

0

A

b

-

1

5

A

b

-

1

0

A

b

-

0

5

A

b

-

0

1

Fig. 2. Intensity profile of a plasma sample. A bead mixture composed of 68 antibodies was employed to determine

intensity levels for the targeted proteins in a plasma sample. Such profiles typically cover intensity range over more than

two orders of magnitude (50–20,000 AU). Standard deviations of £20% can be commonly obtained from replicates.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1054127-250526164042-b625bca5/85/Protein-Microarray-For-Disease-Analysis-Methods-And-Protocols-1st-Edition-Tanya-Knickerbocker-51-320.jpg)

![This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United

States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away

or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License

included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the

laws of the country where you are located before using this

eBook.

Title: In the Days of Giants: A Book of Norse Tales

Author: Abbie Farwell Brown

Illustrator: E. Boyd Smith

Release date: January 8, 2014 [eBook #44622]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Charlie Howard, and the

Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This

file was produced from images generously made

available

by The Internet Archive)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IN THE DAYS OF

GIANTS: A BOOK OF NORSE TALES ***](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1054127-250526164042-b625bca5/85/Protein-Microarray-For-Disease-Analysis-Methods-And-Protocols-1st-Edition-Tanya-Knickerbocker-60-320.jpg)