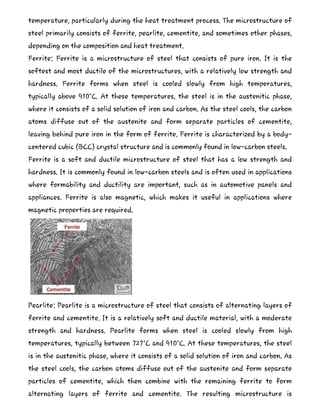

The document discusses the atomic structure of materials and how it determines properties. It covers topics like:

- Atoms are the basic building blocks and consist of protons, neutrons, and electrons

- The three main types of atomic bonding are ionic, covalent, and metallic

- Bonding influences properties like strength, conductivity, and melting points

- Crystalline structure and defects also impact properties

- Engineers can control properties by manipulating atomic arrangement and bonding