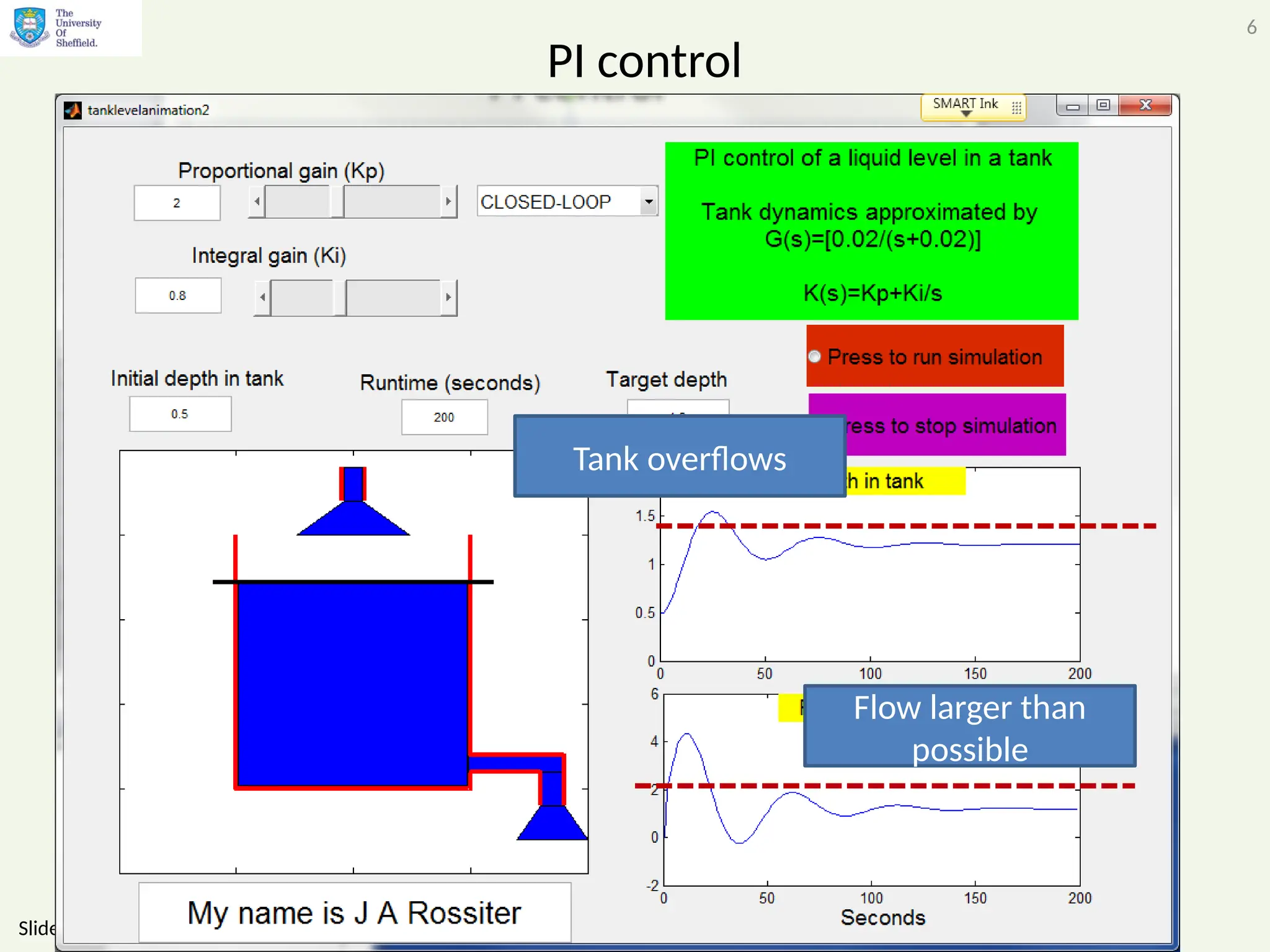

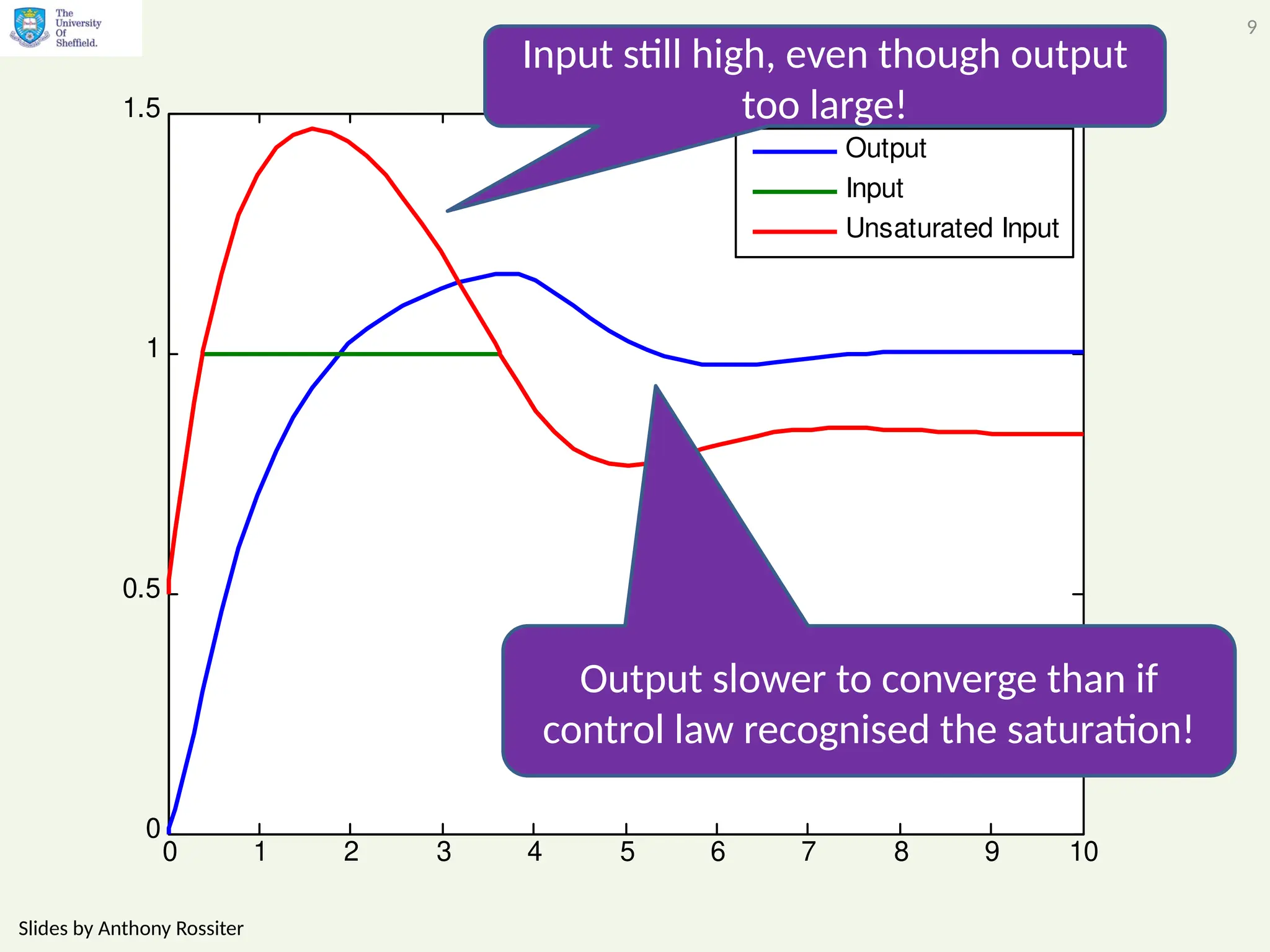

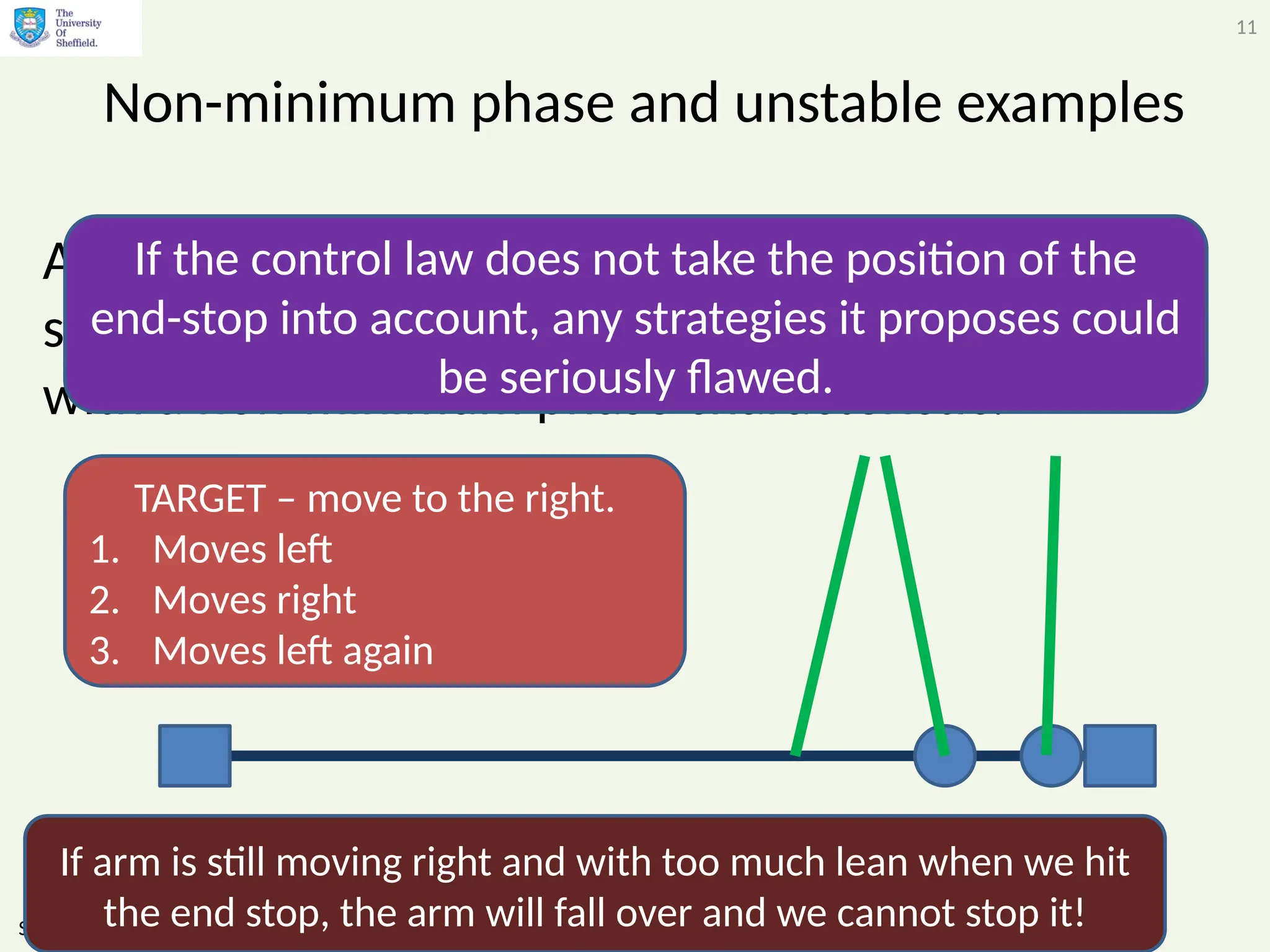

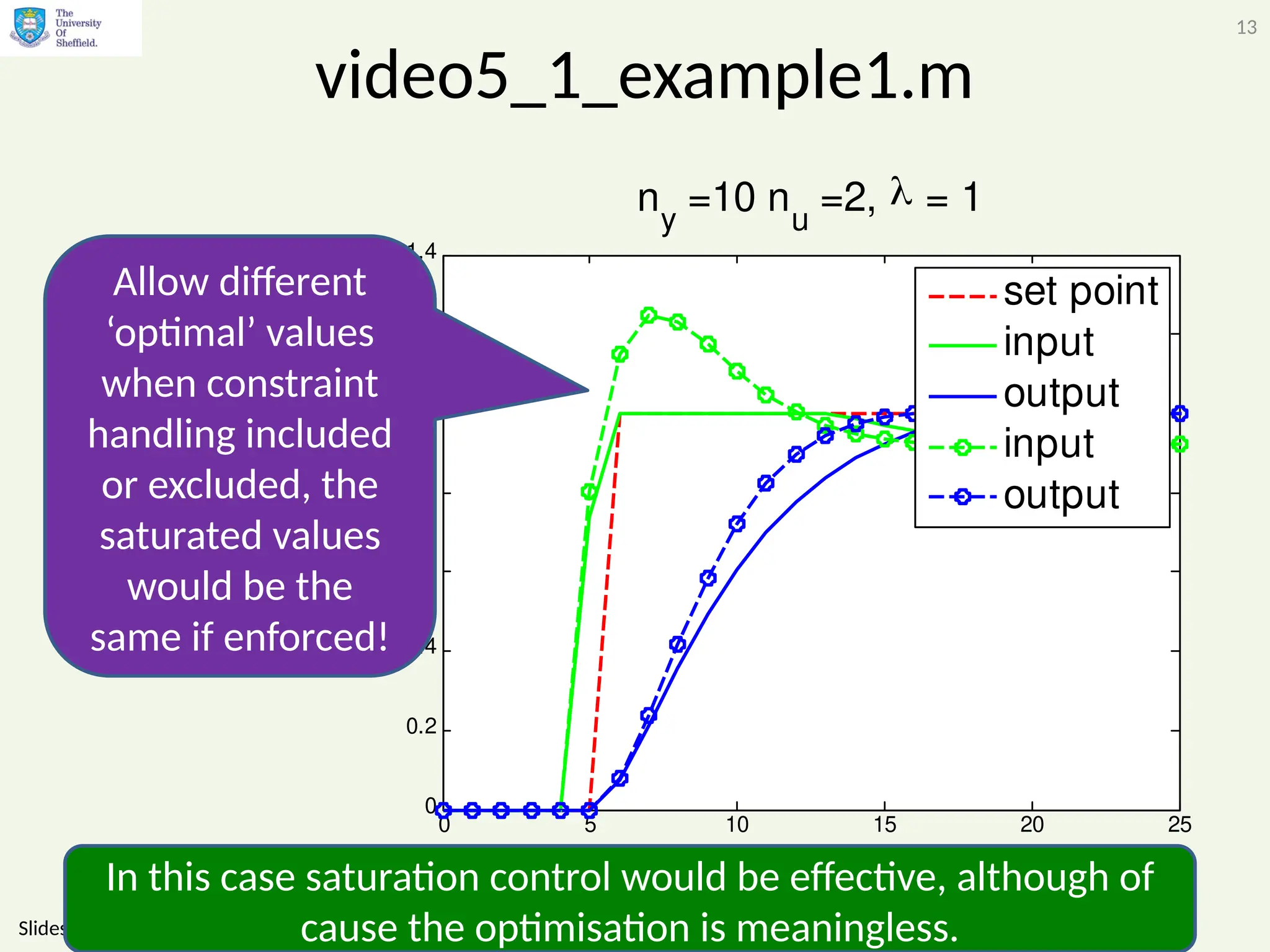

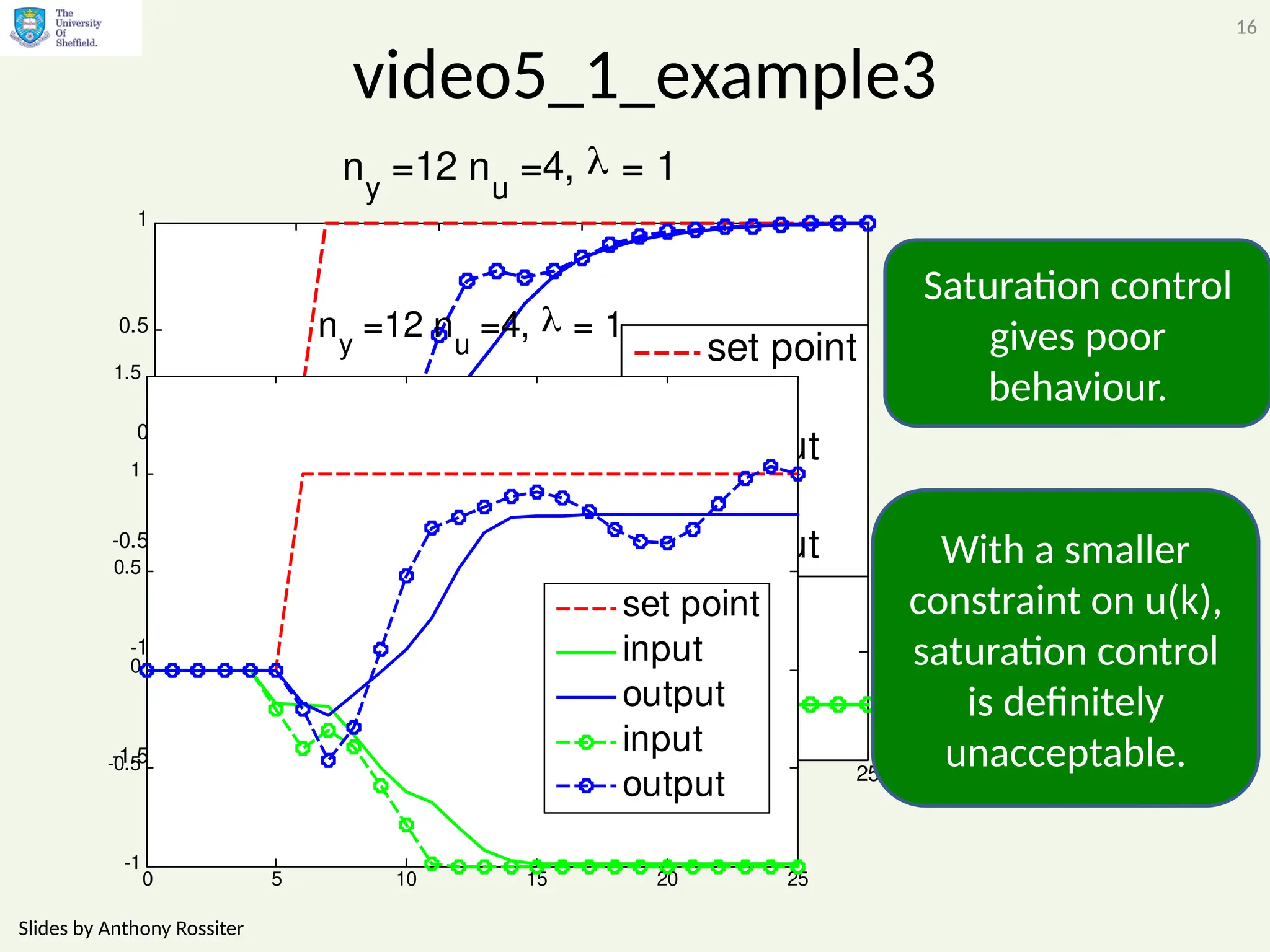

The document discusses the importance of considering constraints in predictive control systems, highlighting the potential disasters arising from ignoring them. It illustrates various examples, including issues like integral wind-up and non-minimum phase systems, emphasizing that systematic integration of constraints leads to improved control effectiveness. The conclusion reiterates that failing to account for constraints can result in suboptimal performance or system failures, necessitating careful design considerations.