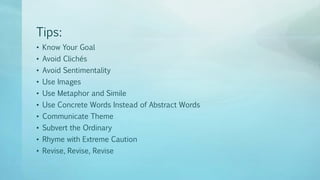

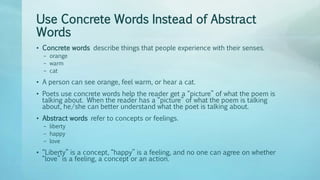

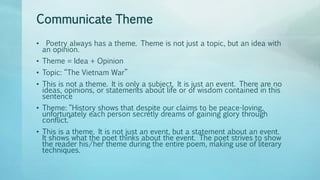

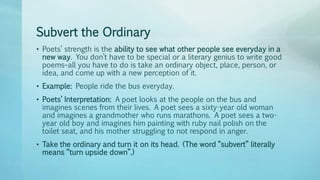

The document provides ten essential tips for writing poetry, focusing on the transition from self-centered expression to creating feelings in readers. Key advice includes knowing your poem's goal, avoiding clichés and sentimentality, using concrete imagery and metaphors, communicating a theme, and revising extensively. The overall emphasis is on finding originality and emotional resonance while maintaining literary quality.