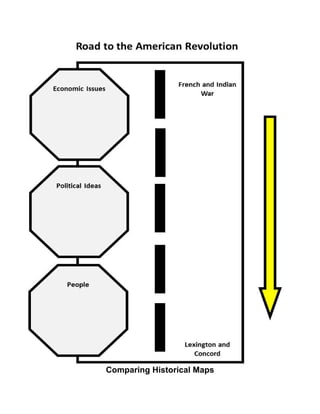

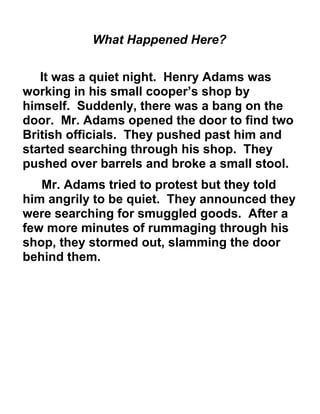

This document provides ideas for enhancing a 5th grade unit on the Road to the Revolution. It includes 11 suggestions or "PIMPs" with activities such as adding a timeline, organizing a field trip to Fort Necessity, having students rewrite lyrics to "Yankee Doodle", and showing videos about important historical figures like George Washington and Benjamin Franklin. The PIMPs aim to make the lessons more hands-on and help students better understand the events and people that led to the American Revolution.

![Reference Page

(in order of use)

"Atlas - Unit 5: Road to Revolution." Atlas - Unit 5: Road to Revolution. Rubicon International,

2014. Web. 10 Nov. 2014.

< http://oaklandk12-public.rubiconatlas.org/Atlas/Browse/UnitMap/View/Default?

BackLink=291493&strkeys=social+studies&UnitID=13492&YearID=2015&CurriculumMapID=112&

SourceSiteID=2599>

Education Program for 4th, 5th & 6th Grade Classes. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2014.

< http://www.nps.gov/fone/forteachers/upload/FONE-4th-Grade-FandI-SiteB_NBl_pc2012.pdf>

Digital History. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2014.

< http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/era.cfm?eraID=3&smtID=6>

Yankee Doodle ( American Patriotic Song ). (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2014.

< http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IzRhFH5OyHo>

Yankee Doodle. [song sheet]:Song Sheet Enlargement: Performing Arts Encyclopedia, Library of

Congress. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2014.

<http://lcweb2.loc.gov/diglib/ihas/loc.rbc.hc.00037b/enlarge.html?page=1&from=pageturner>

The Ben Franklin Story - Archiving Early America. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2014.

<http://www.earlyamerica.com/videos/ben-franklin-story/>

Colonial Fort Michilimackinac - Mackinaw City, Michigan. (n.d.). Retrieved November 8, 2014.

<http://www.mightymac.org/michilimackinac.htm>

Pontiac's Rebellion.wmv. (n.d.). Retrieved November 8, 2014.

< http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KVx0Is3XKu0&spfreload=10>

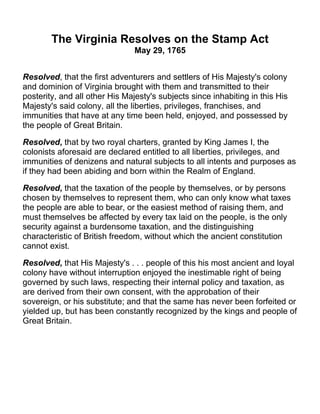

Stamp Act. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2014.

<http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h642.html>

The Stamp Act - HistoryWiz American Revolution. (n.d.). Retrieved November 7, 2014.

< http://www.historywiz.com/stampact.htm>

Samuel Adams. (n.d.). Retrieved November 8, 2014.

<http://www.history.com/topics/american-revolution/samuel-adams>

Patrick Henry. (2014). The Biography.com website. Retrieved Nov 08, 2014.

<http://www.biography.com/people/patrick-henry-9335512>

EMS Social Studies (n.d.). Retrieved November 8, 2014.

http://emssocialstudies.com/documents/Unit_1/The%20Intolerable%20King%20Skit

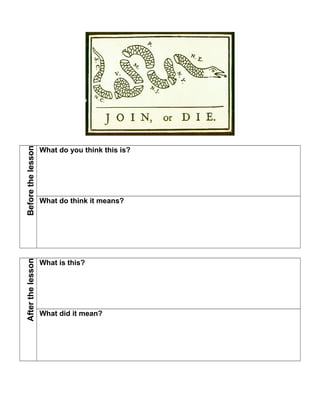

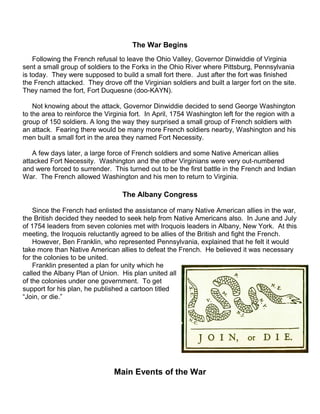

%20Assignment.pdf](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pimpmylessonoseboldt-141110202351-conversion-gate02/85/Pimp-mylesson-oseboldt-8-320.jpg)