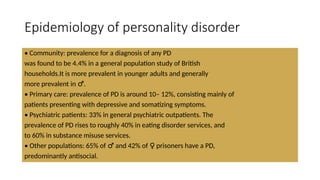

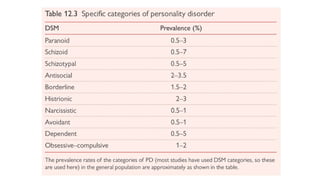

Personality disorders are a group of mental health conditions characterized by enduring patterns of behavior, cognition, and inner experience that deviate from cultural expectations. These patterns are often inflexible and pervasive, leading to significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other areas of functioning.