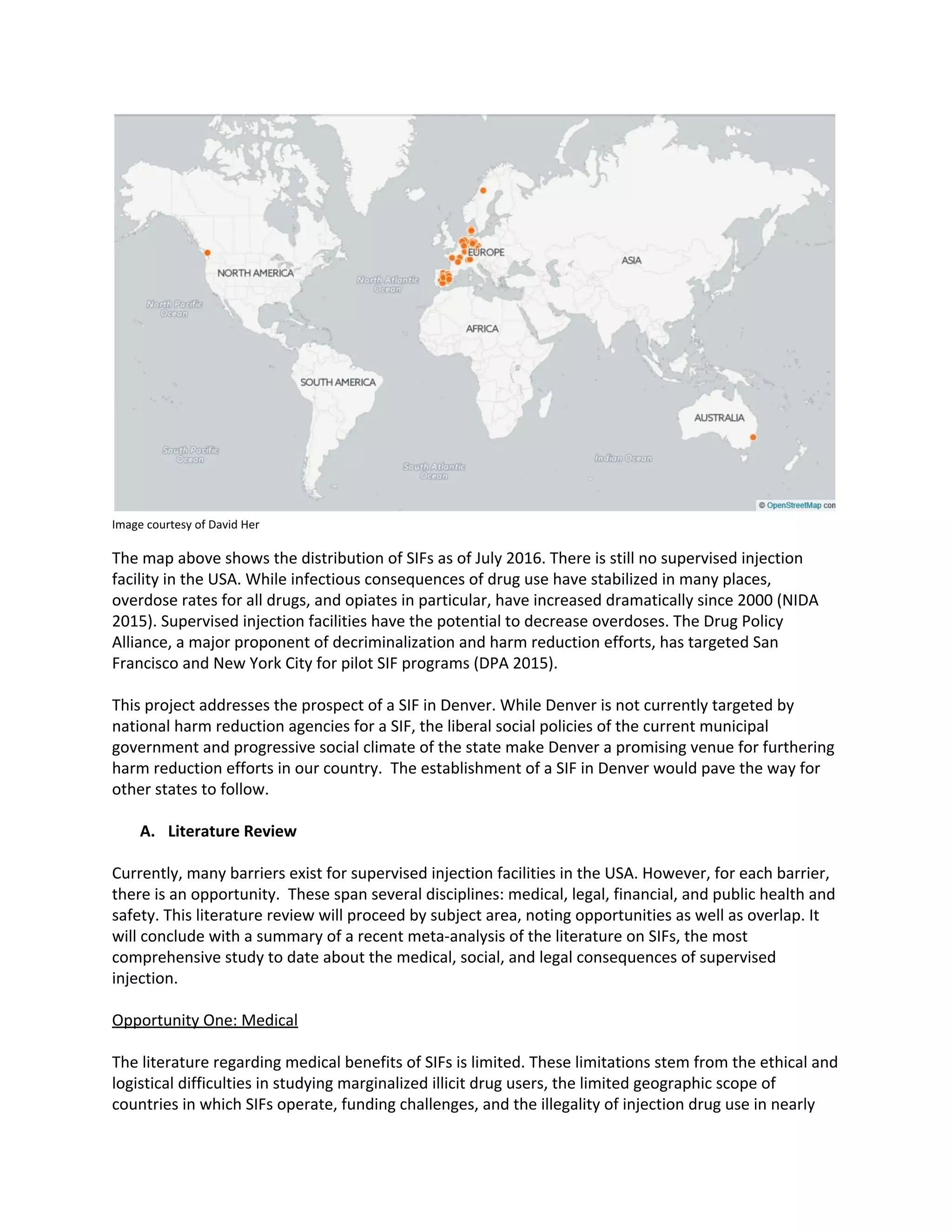

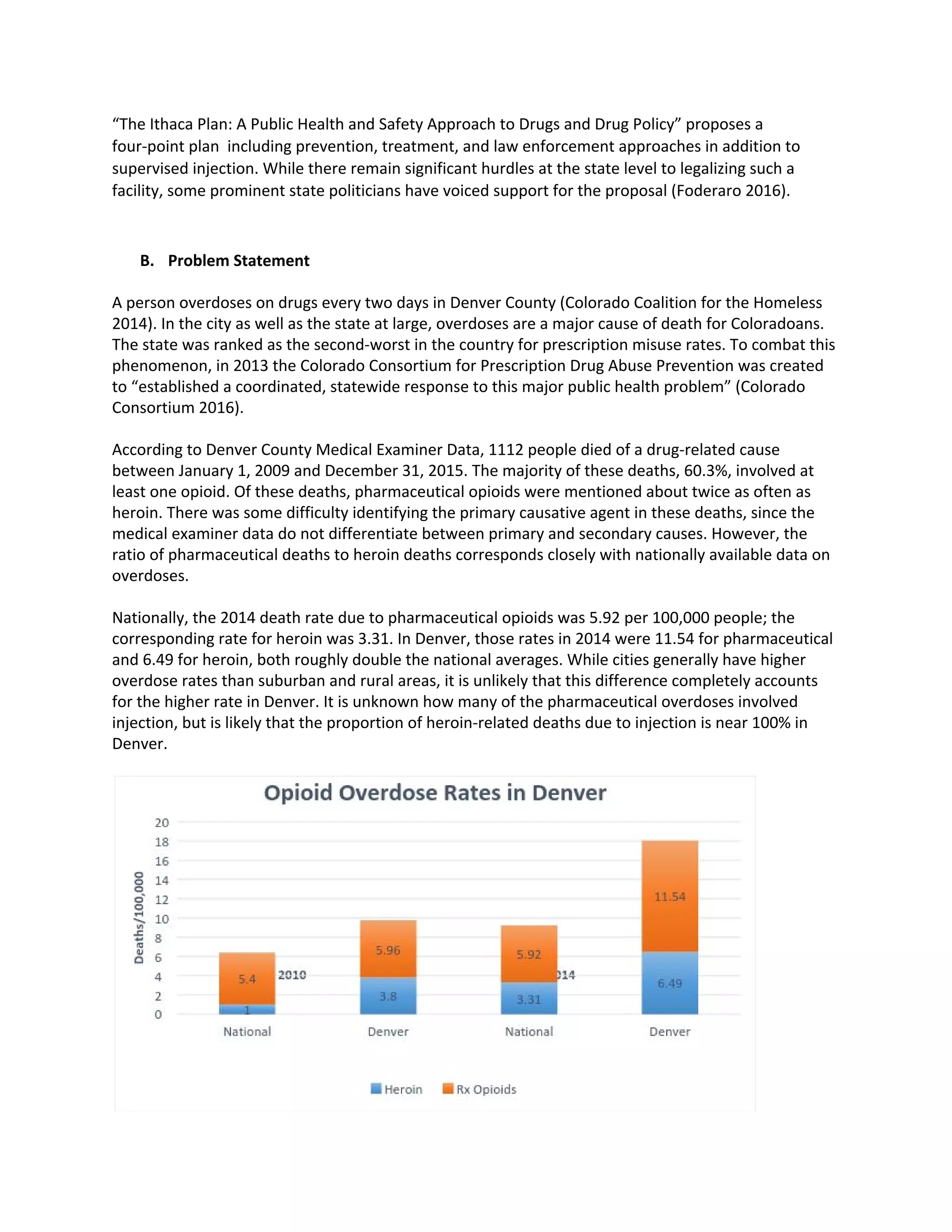

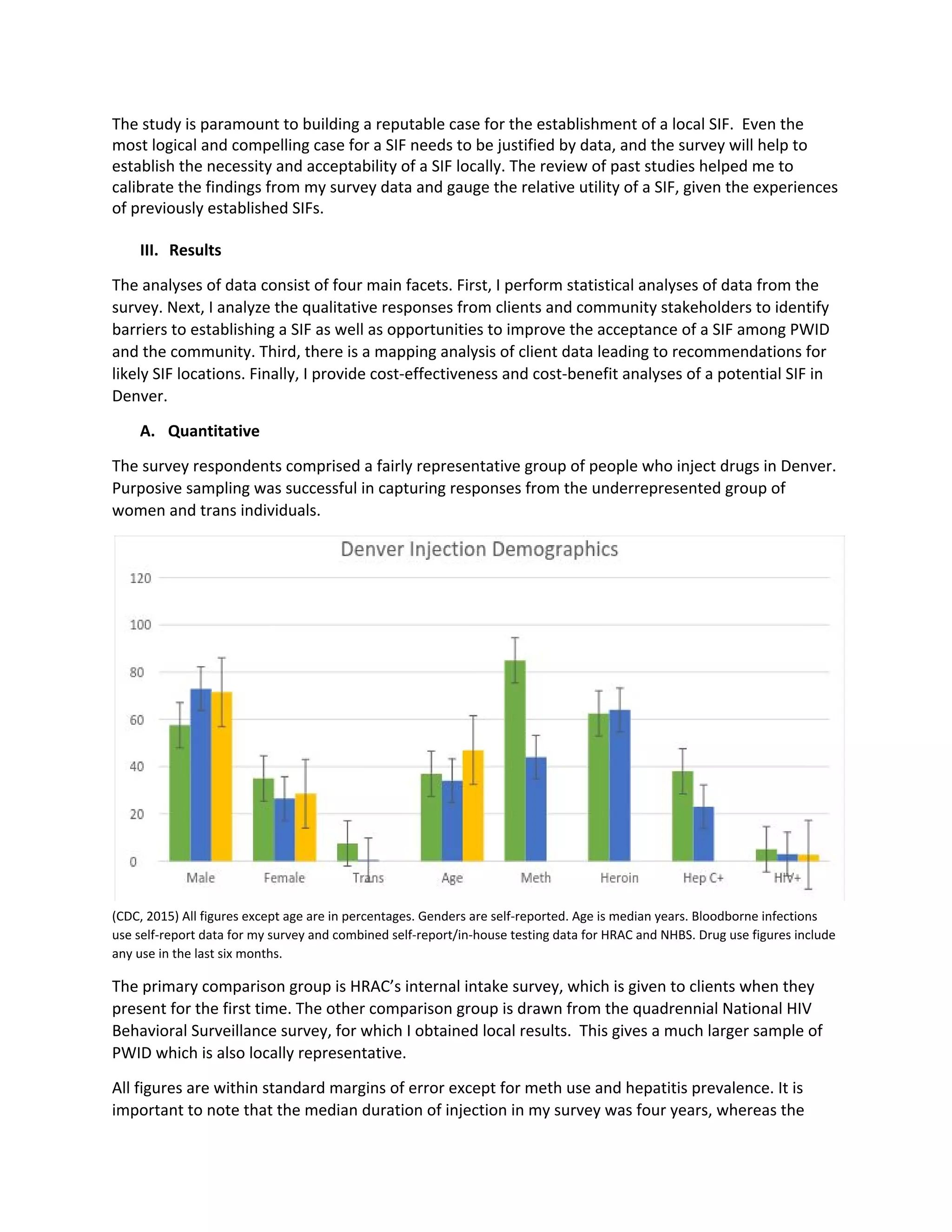

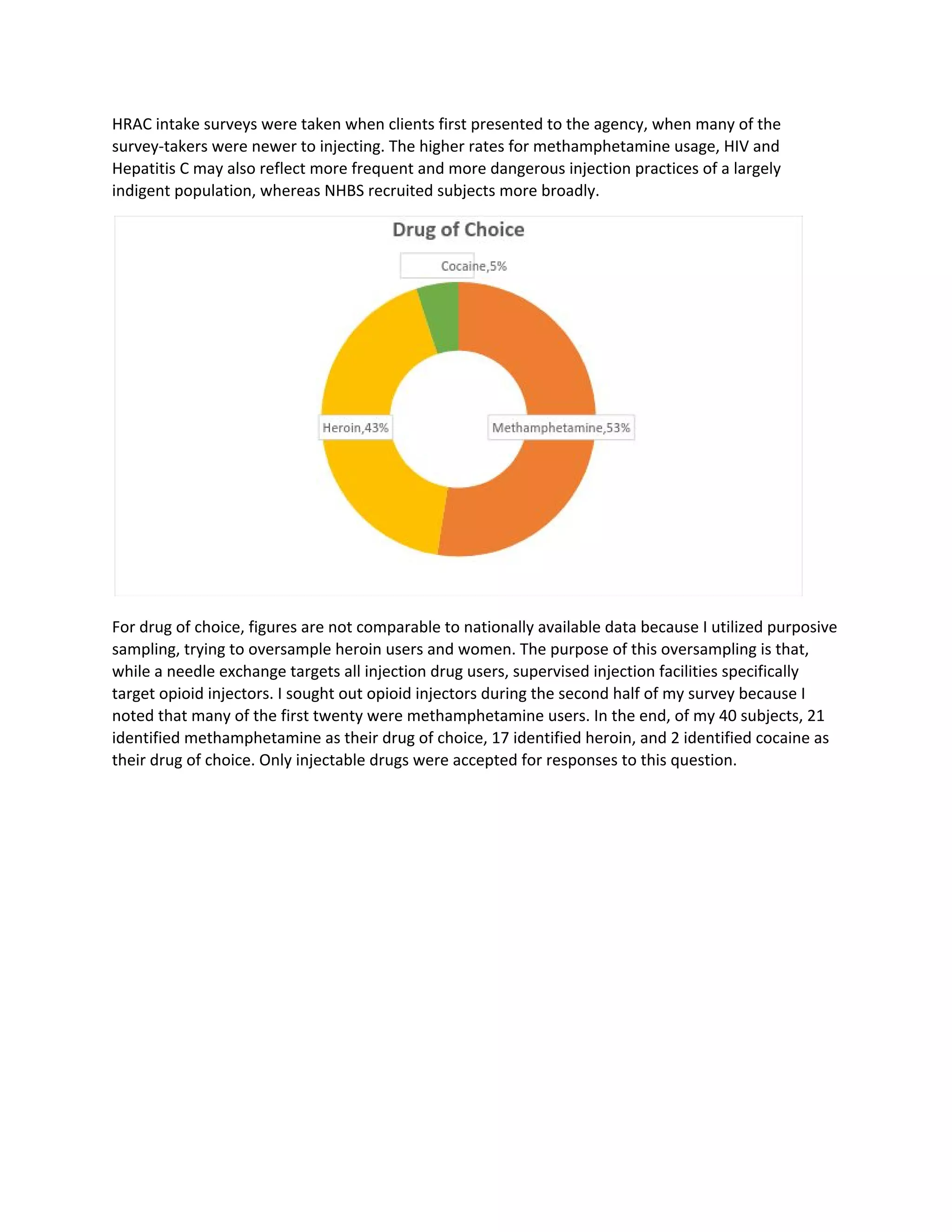

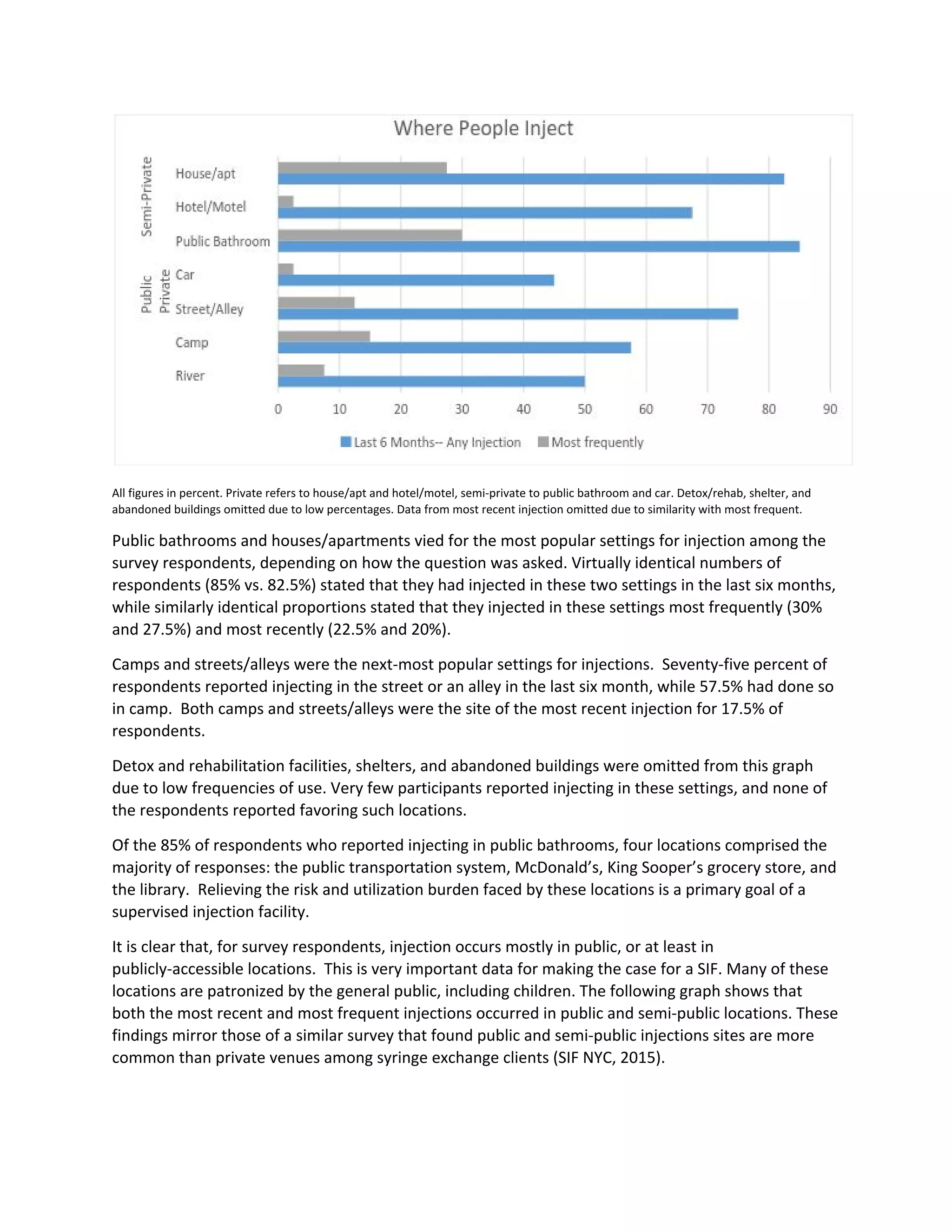

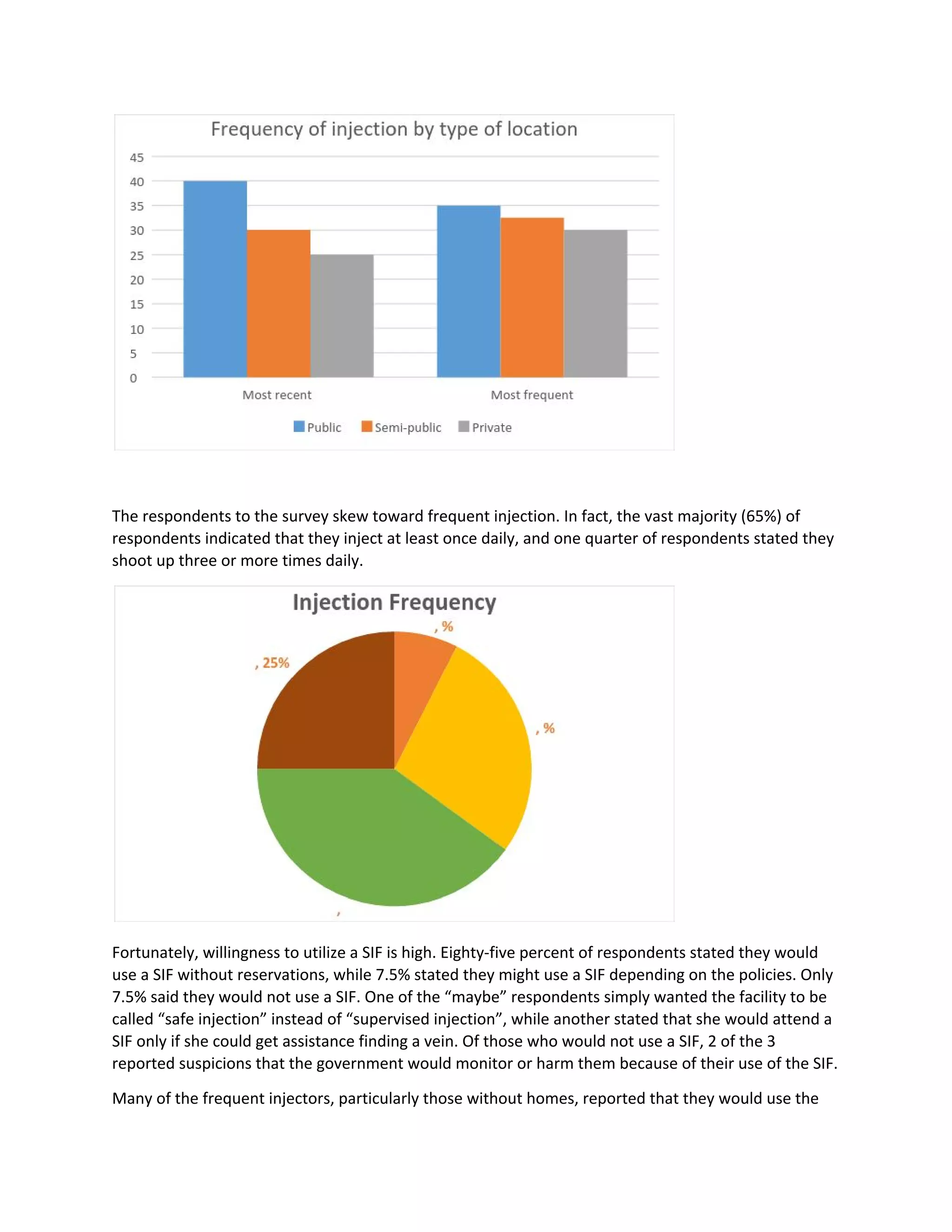

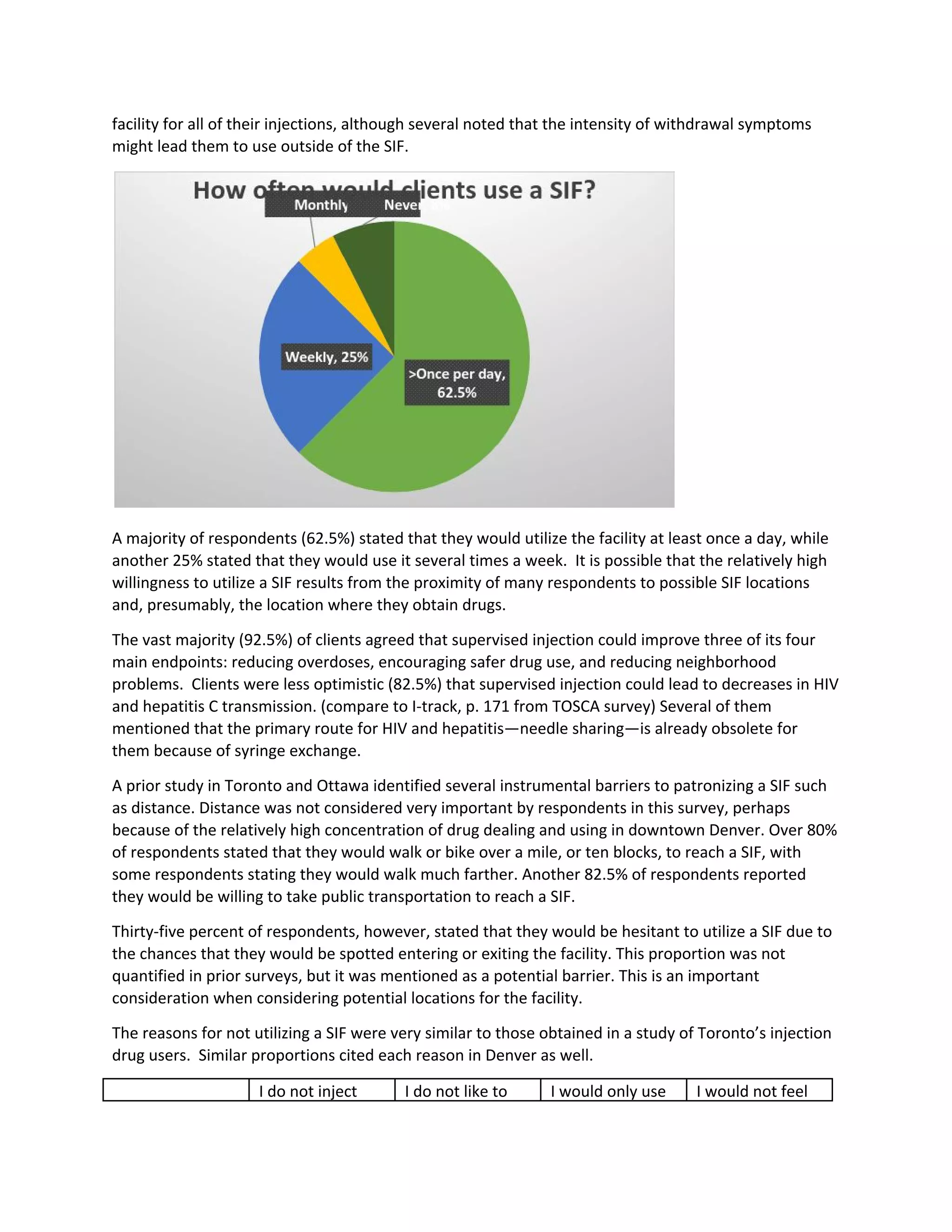

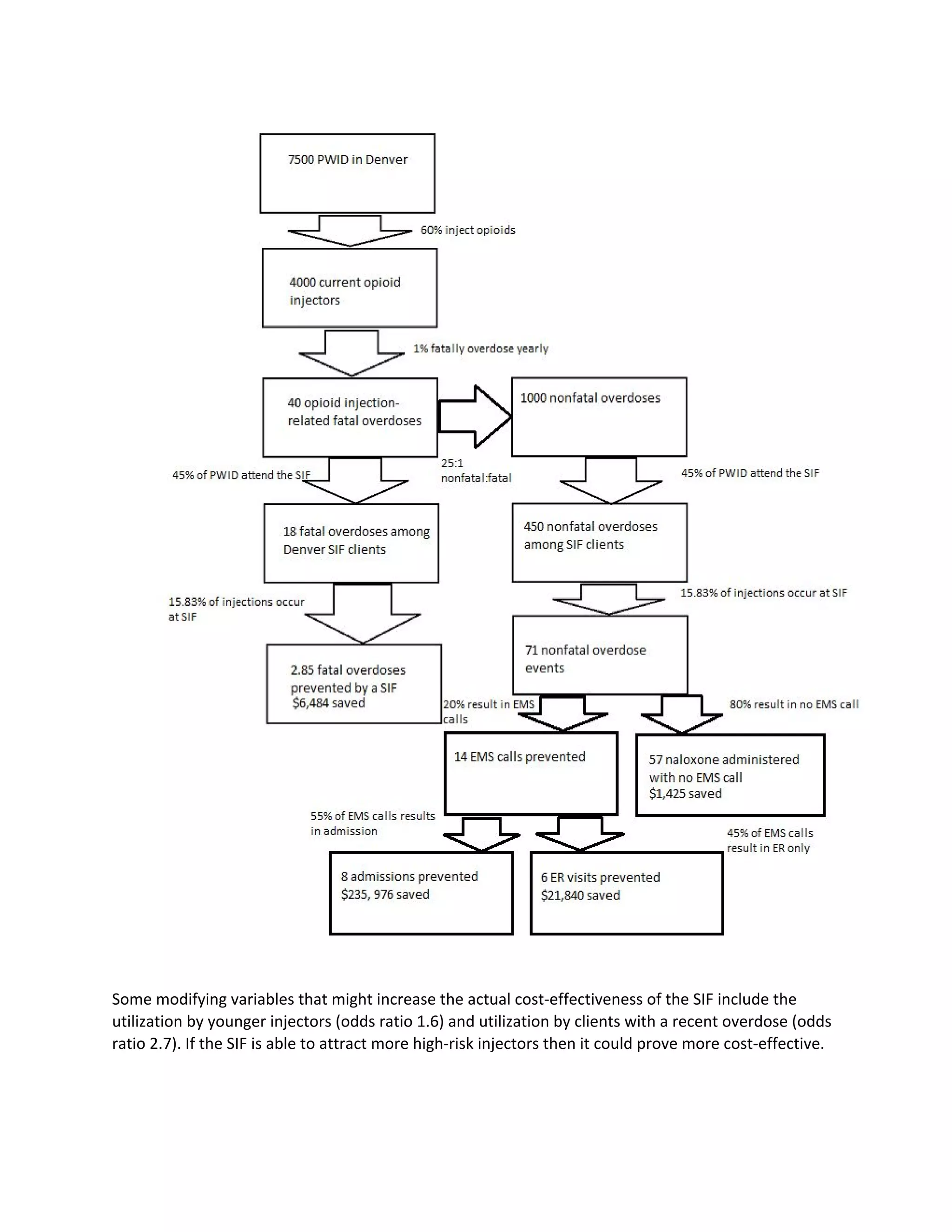

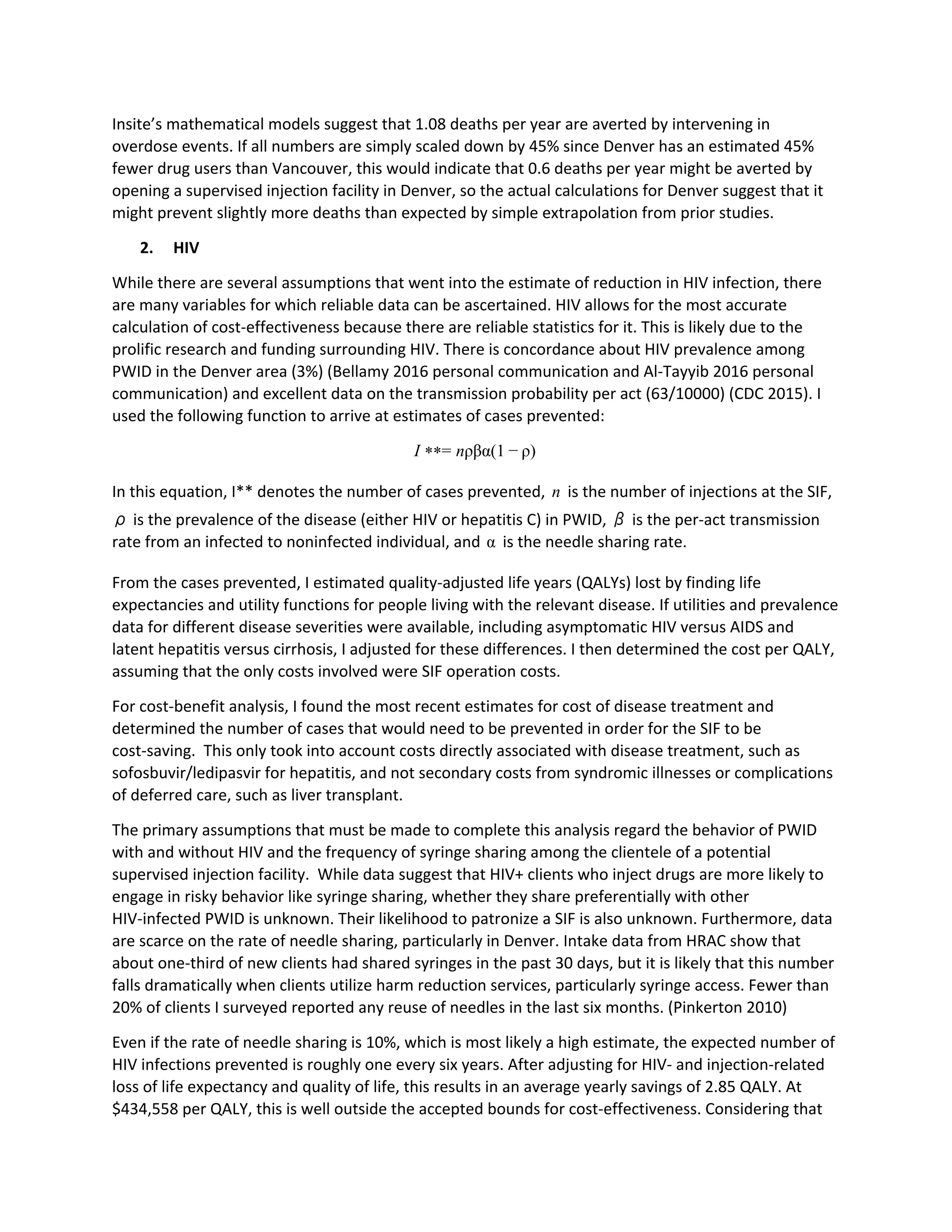

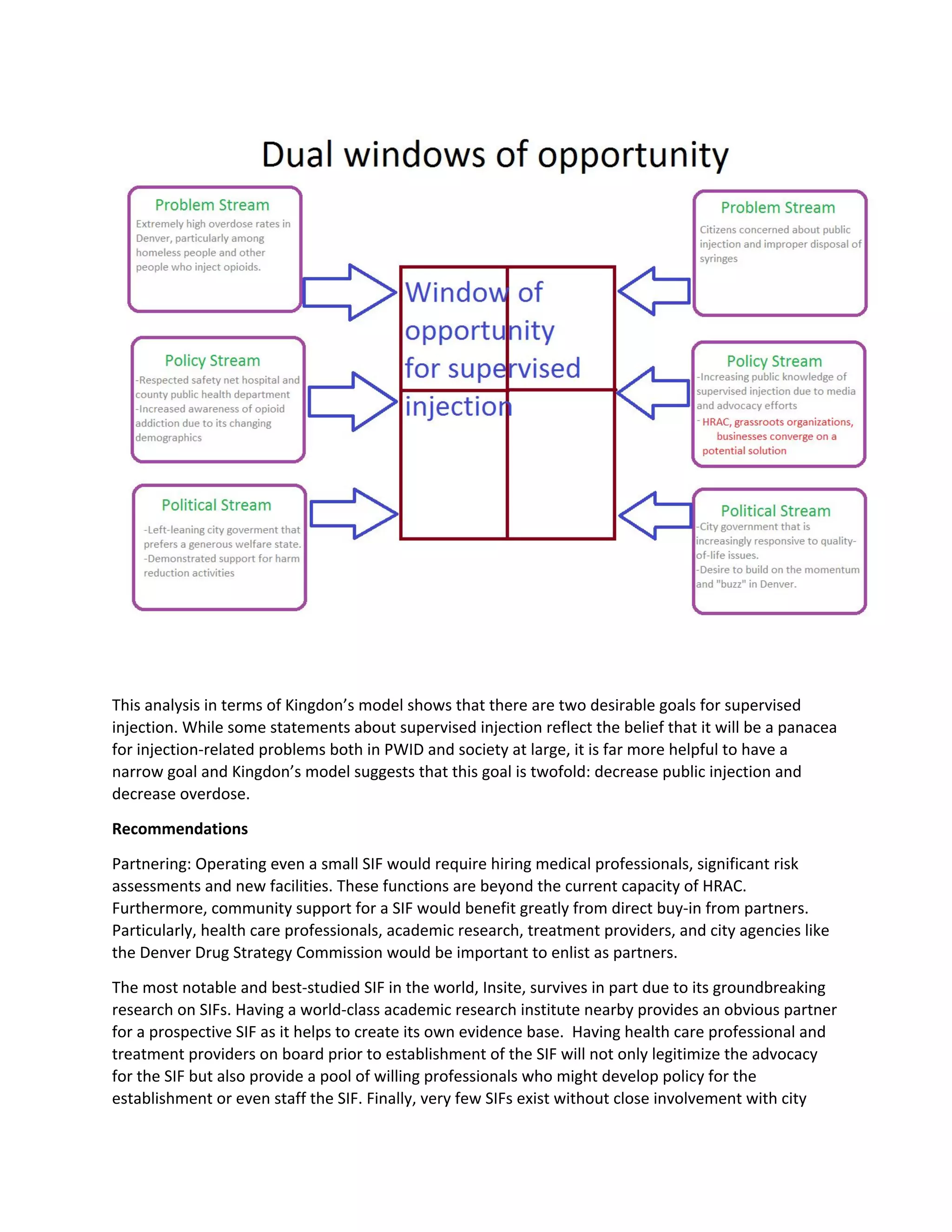

This document discusses establishing a supervised injection facility (SIF) in Denver, Colorado to help address rising drug overdose rates. It provides background on SIFs, which have operated for decades in Europe, Australia, and Canada to reduce public drug use, needle sharing, and overdoses. The proposed study would assess Denver's potential for a SIF through interviews with people who inject drugs and community stakeholders, as well as analyses of spatial mapping and costs/benefits. Recommendations would then be made on next steps for implementing a SIF in Denver.