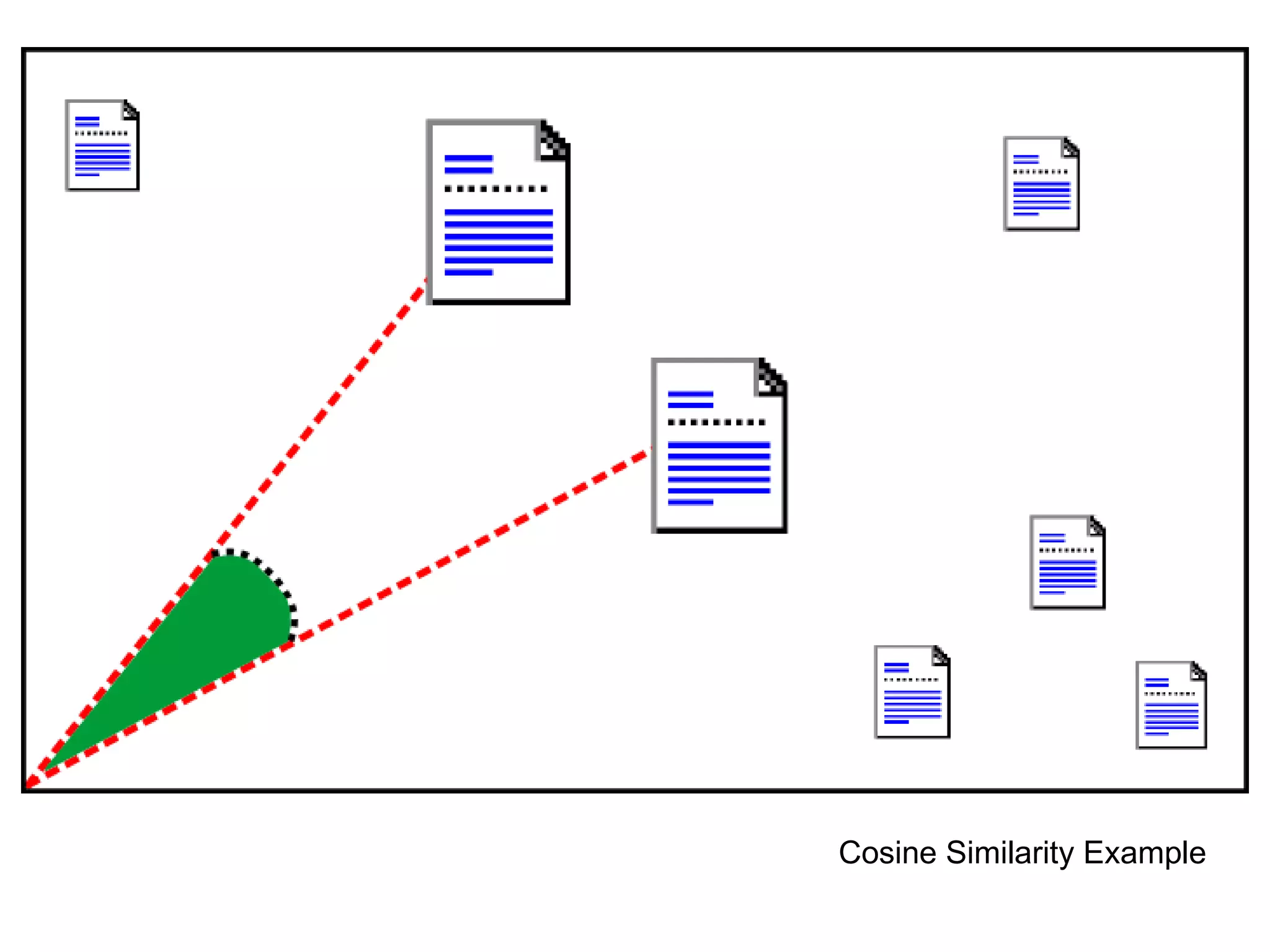

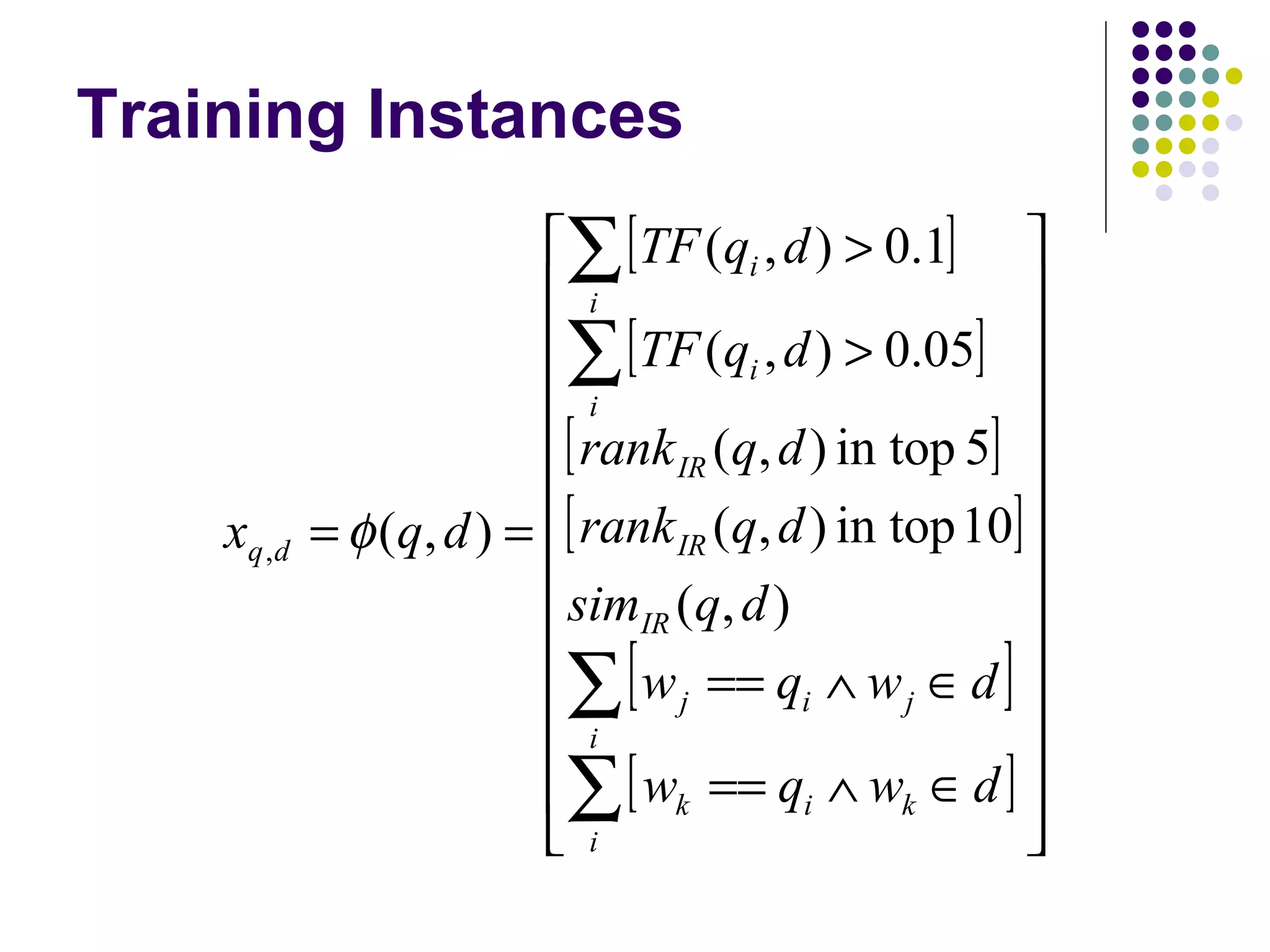

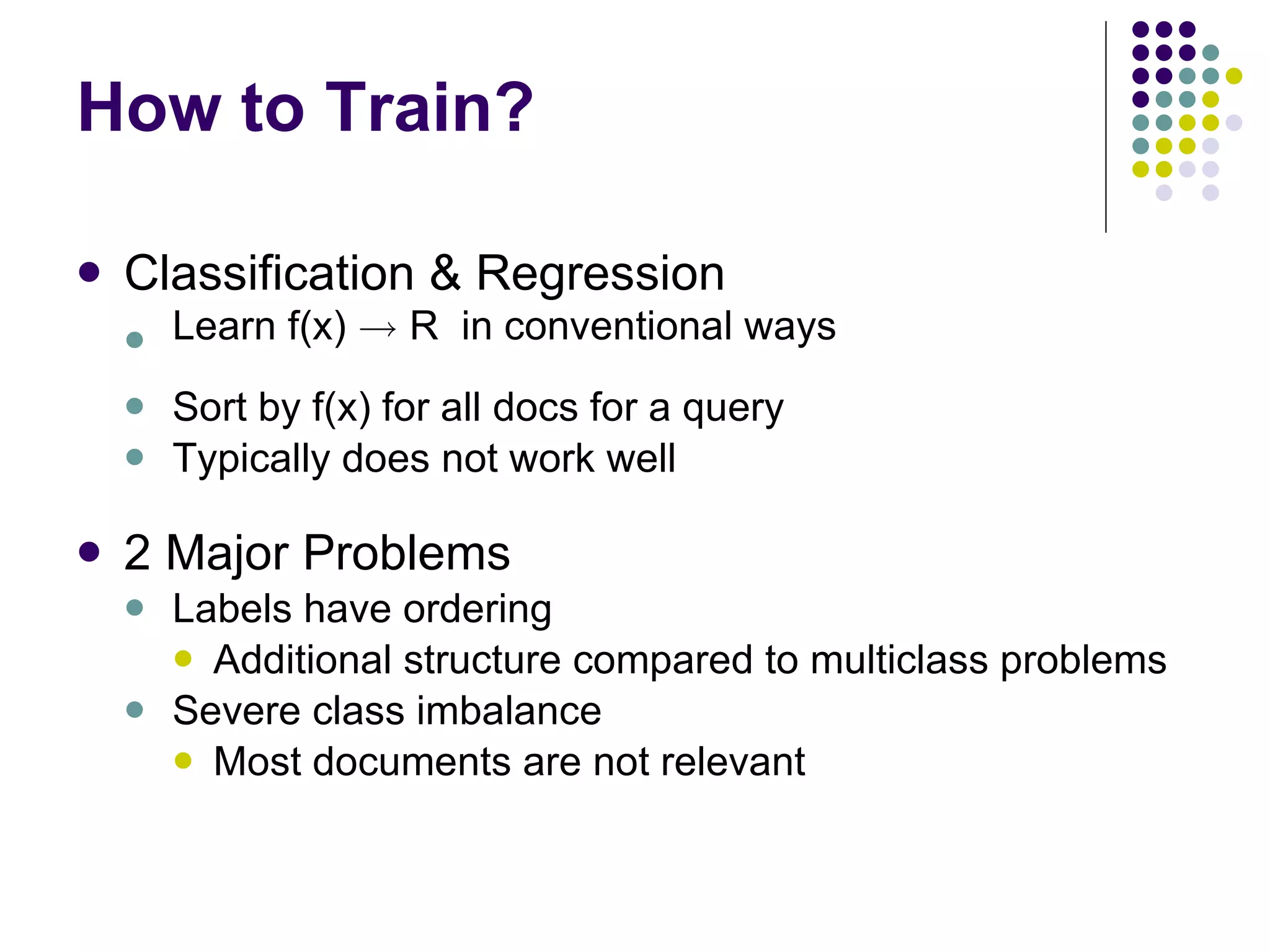

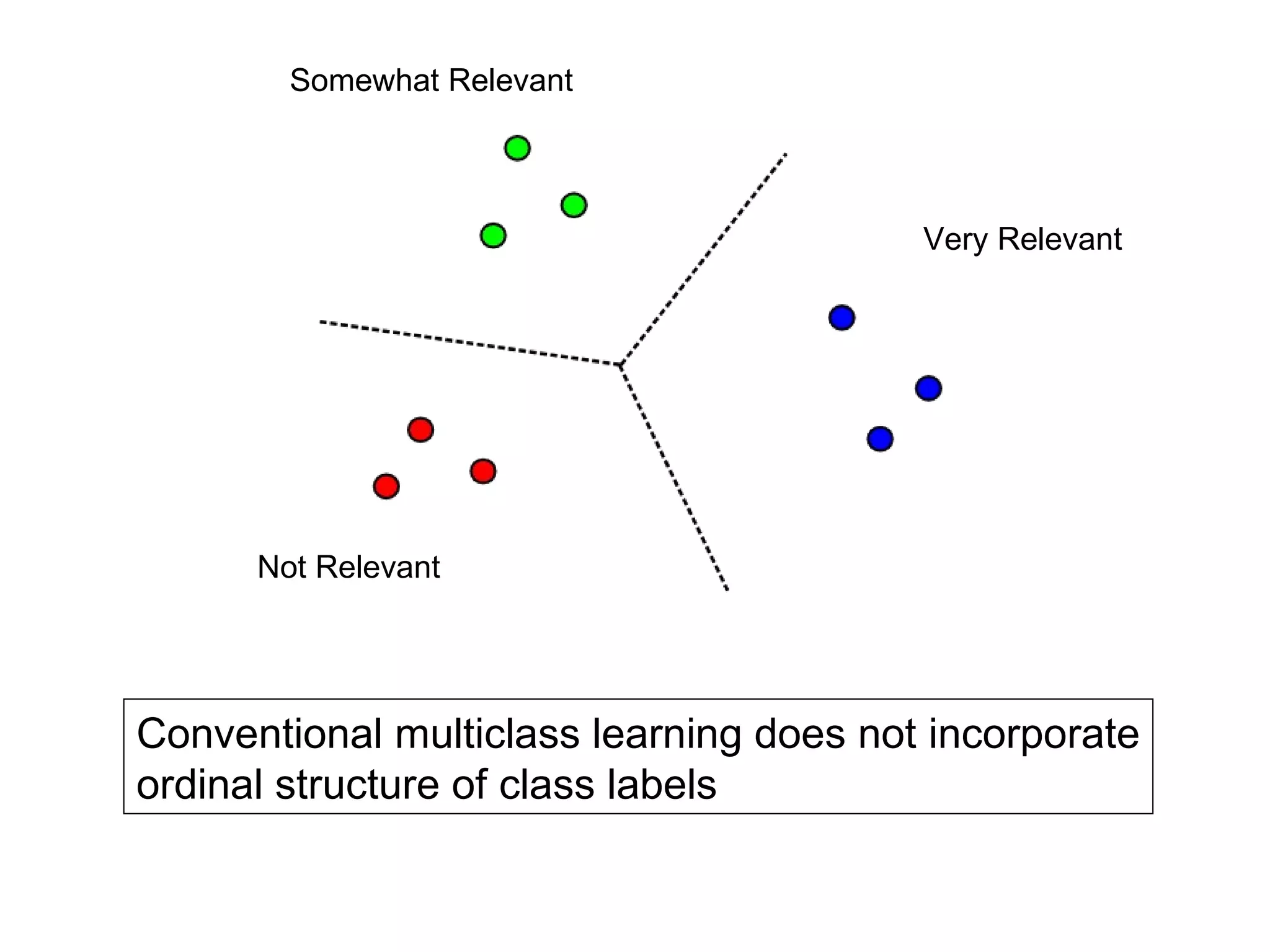

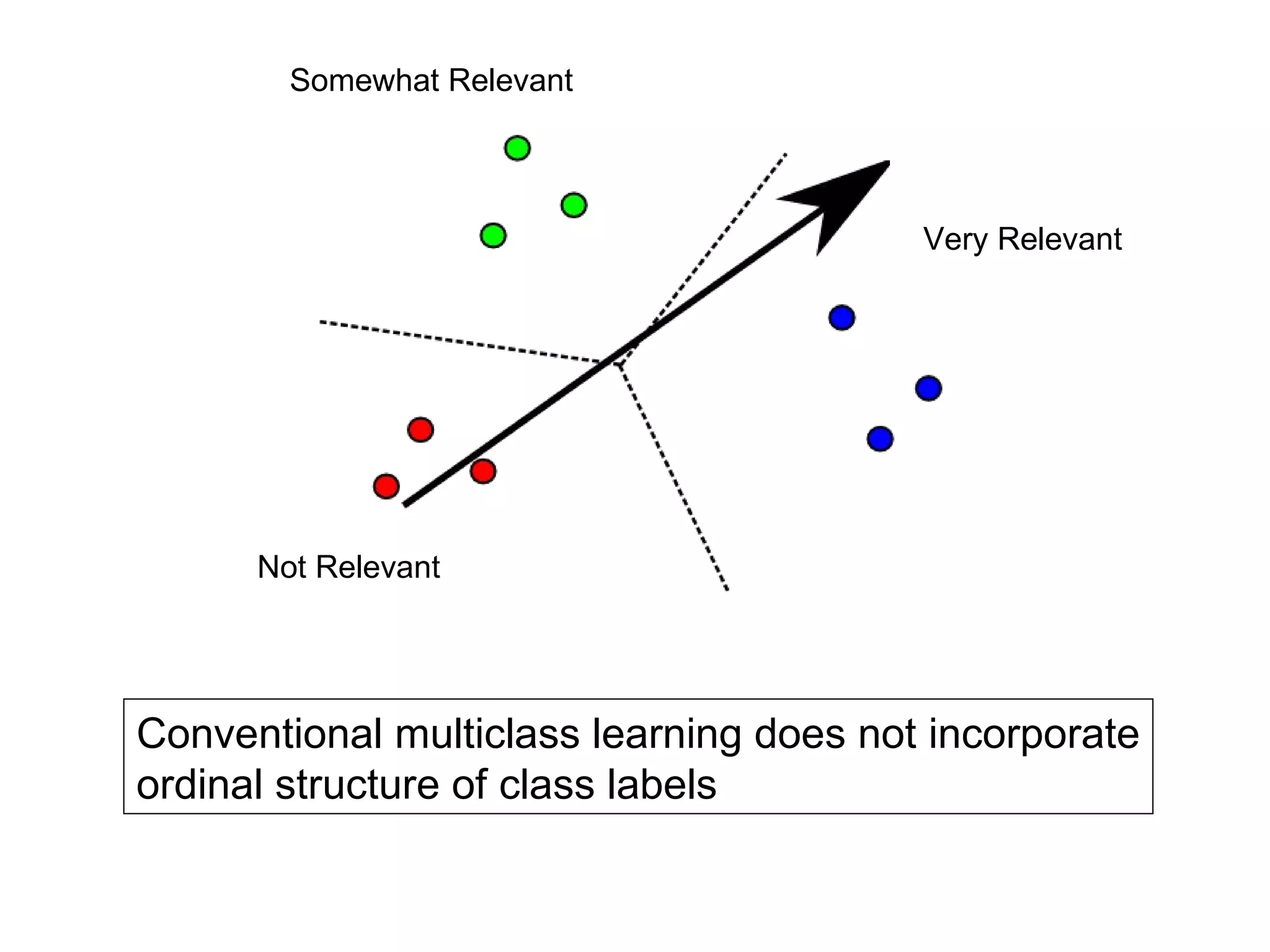

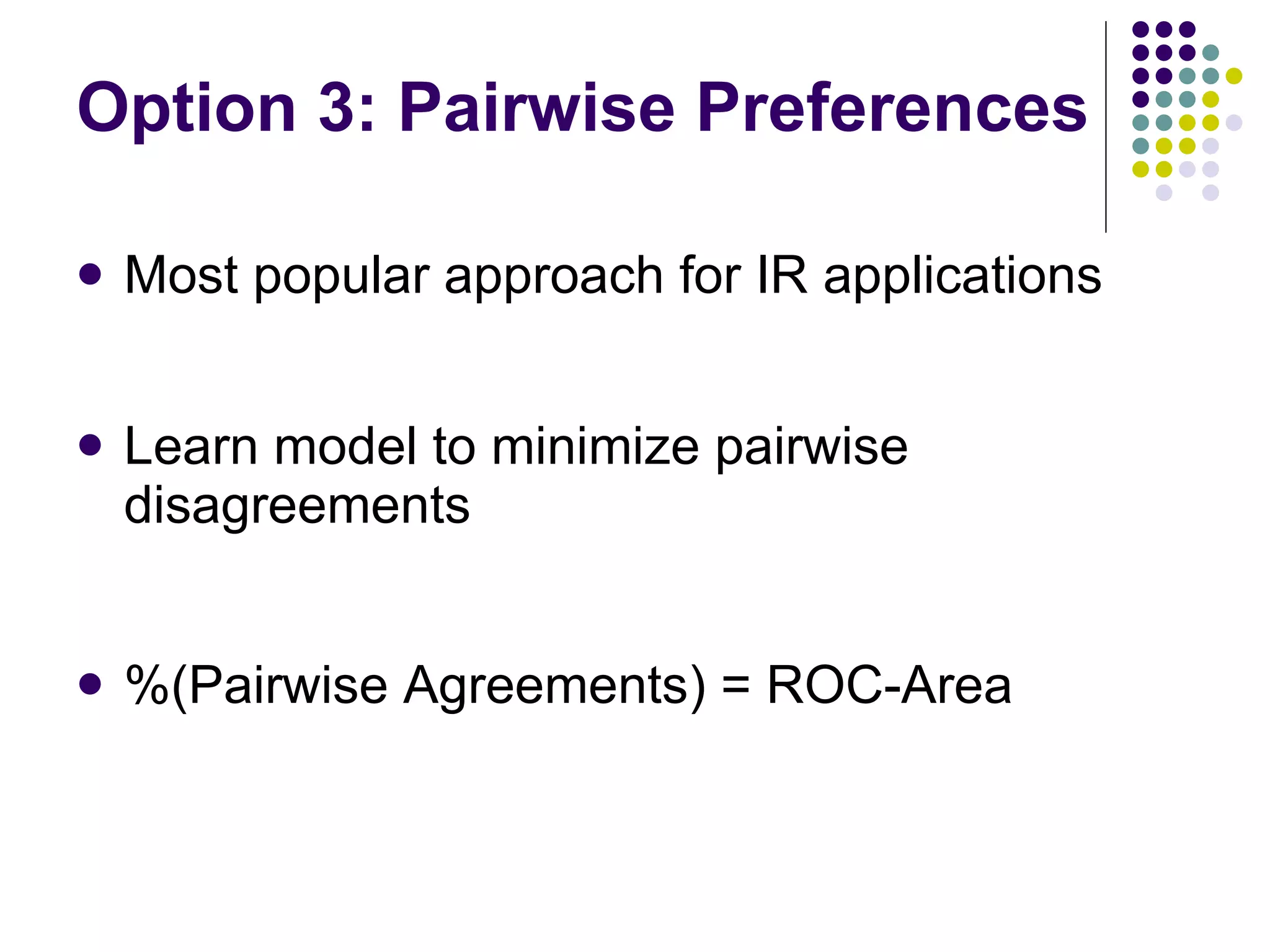

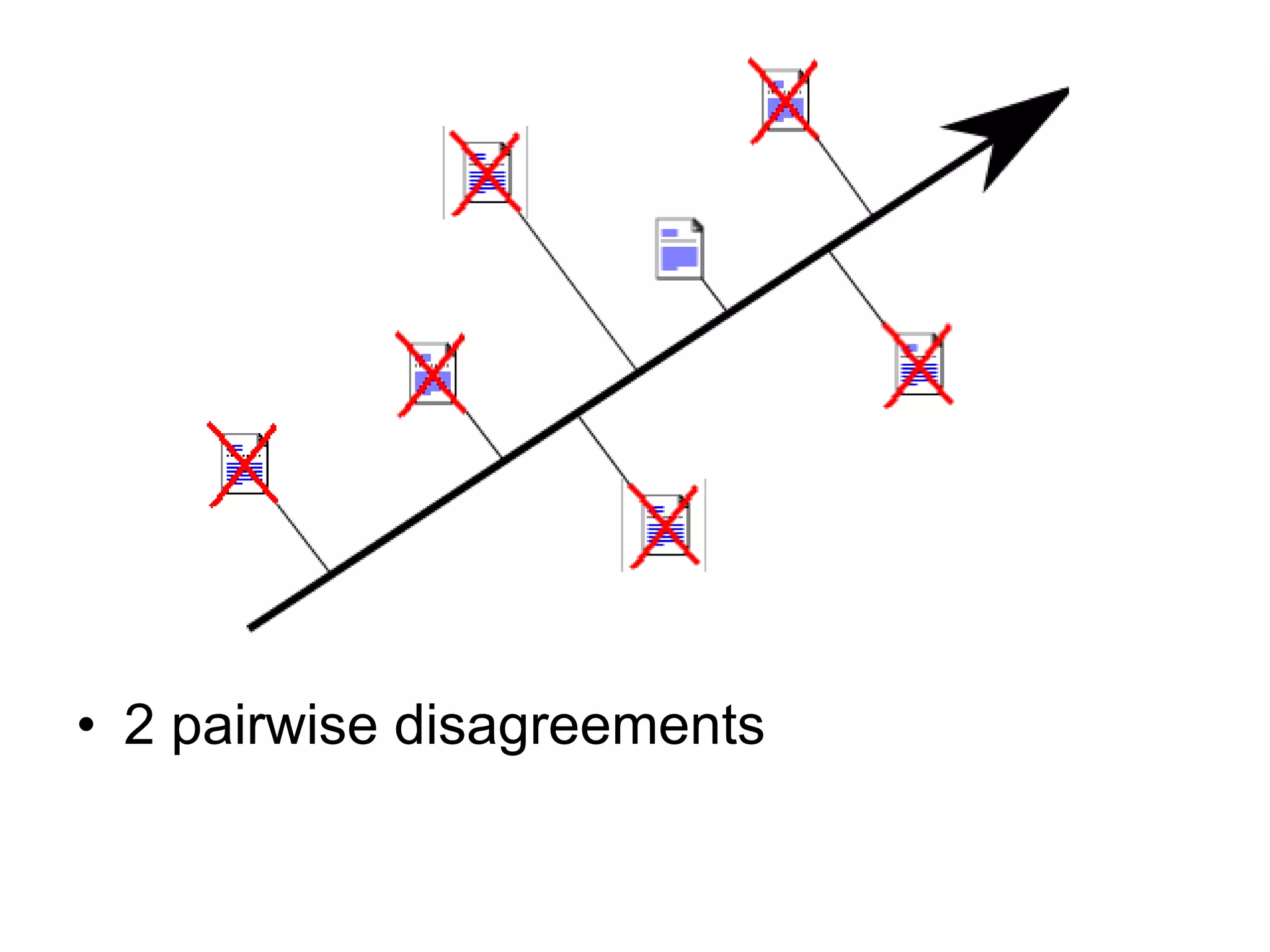

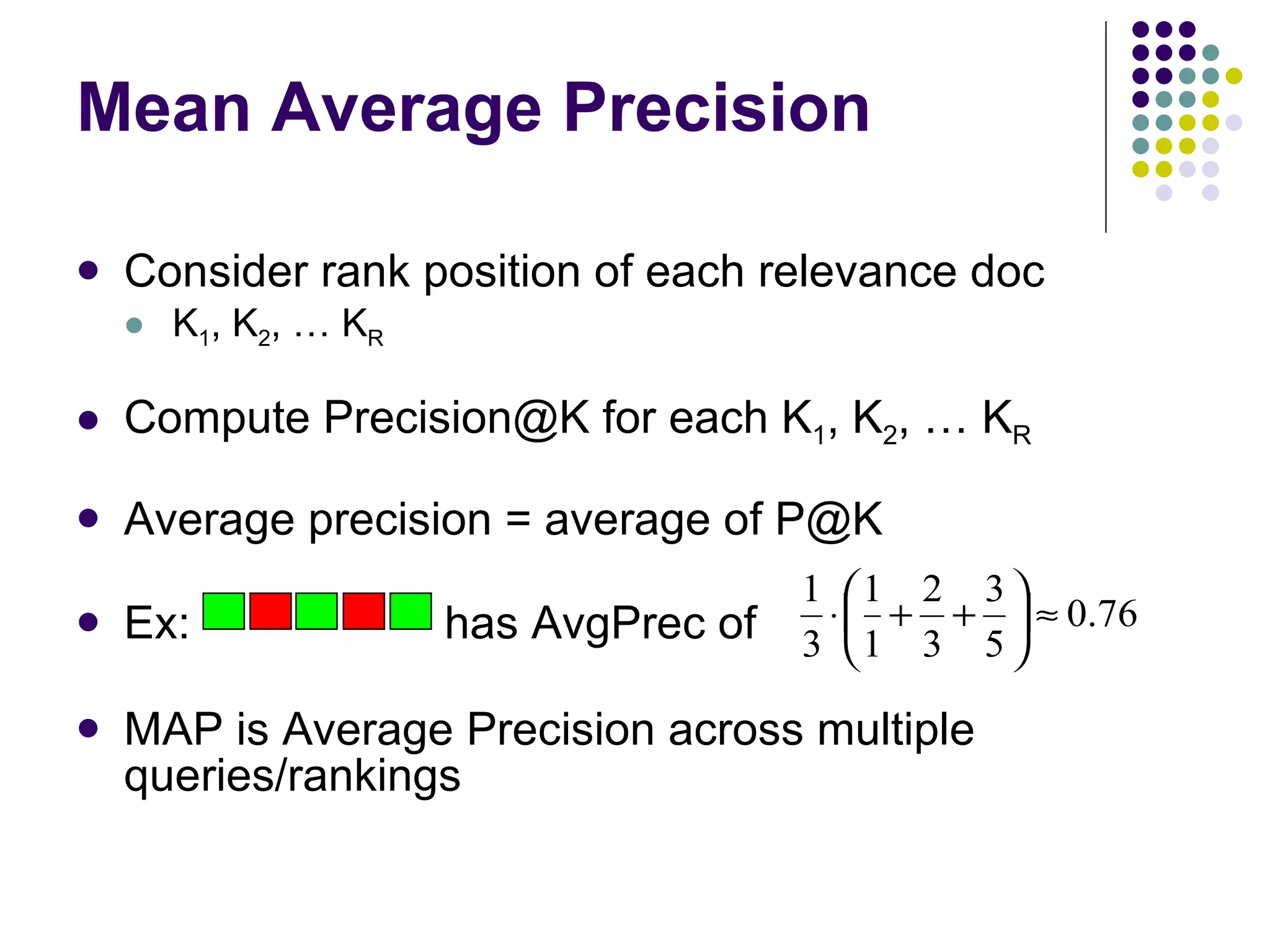

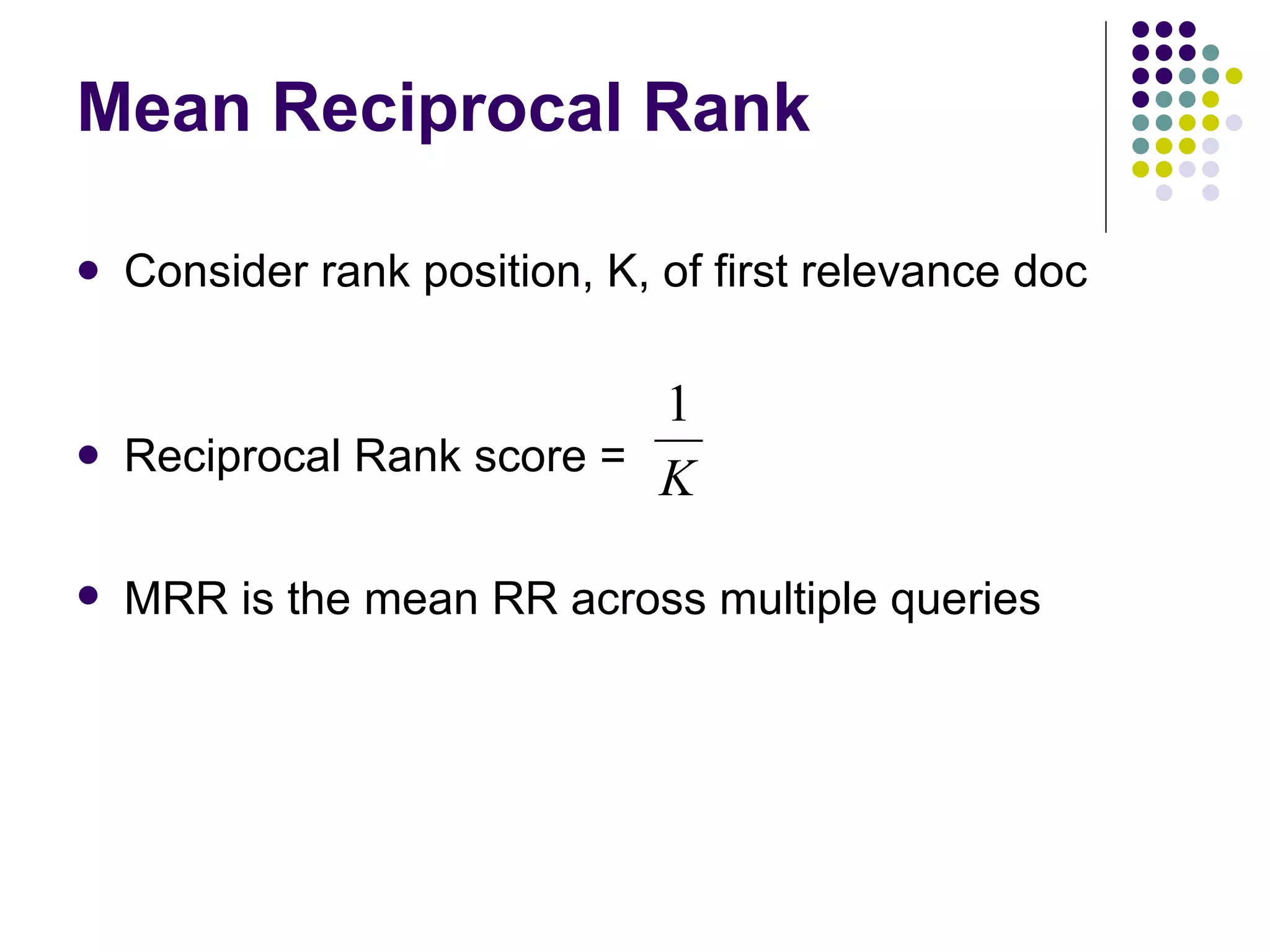

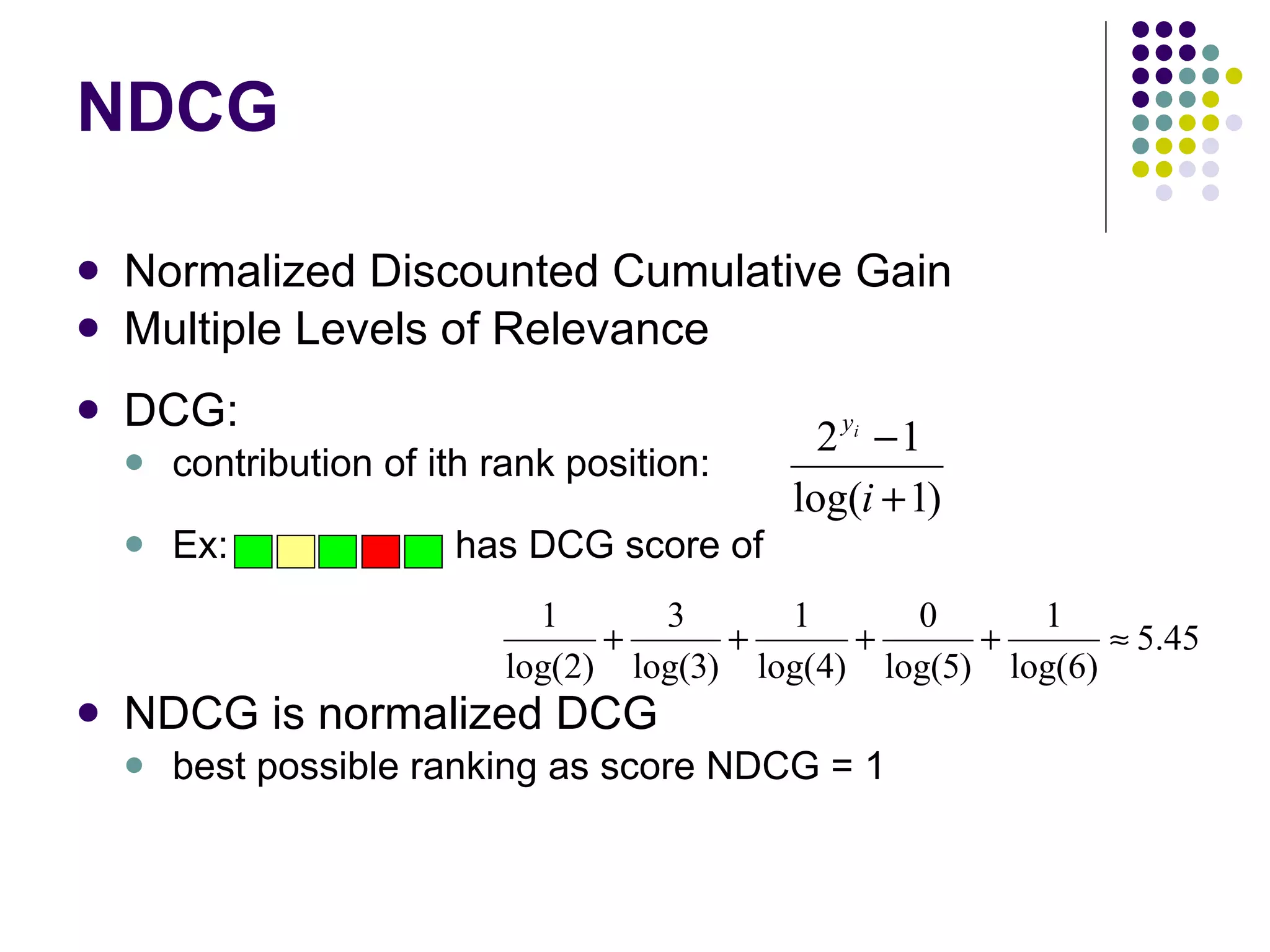

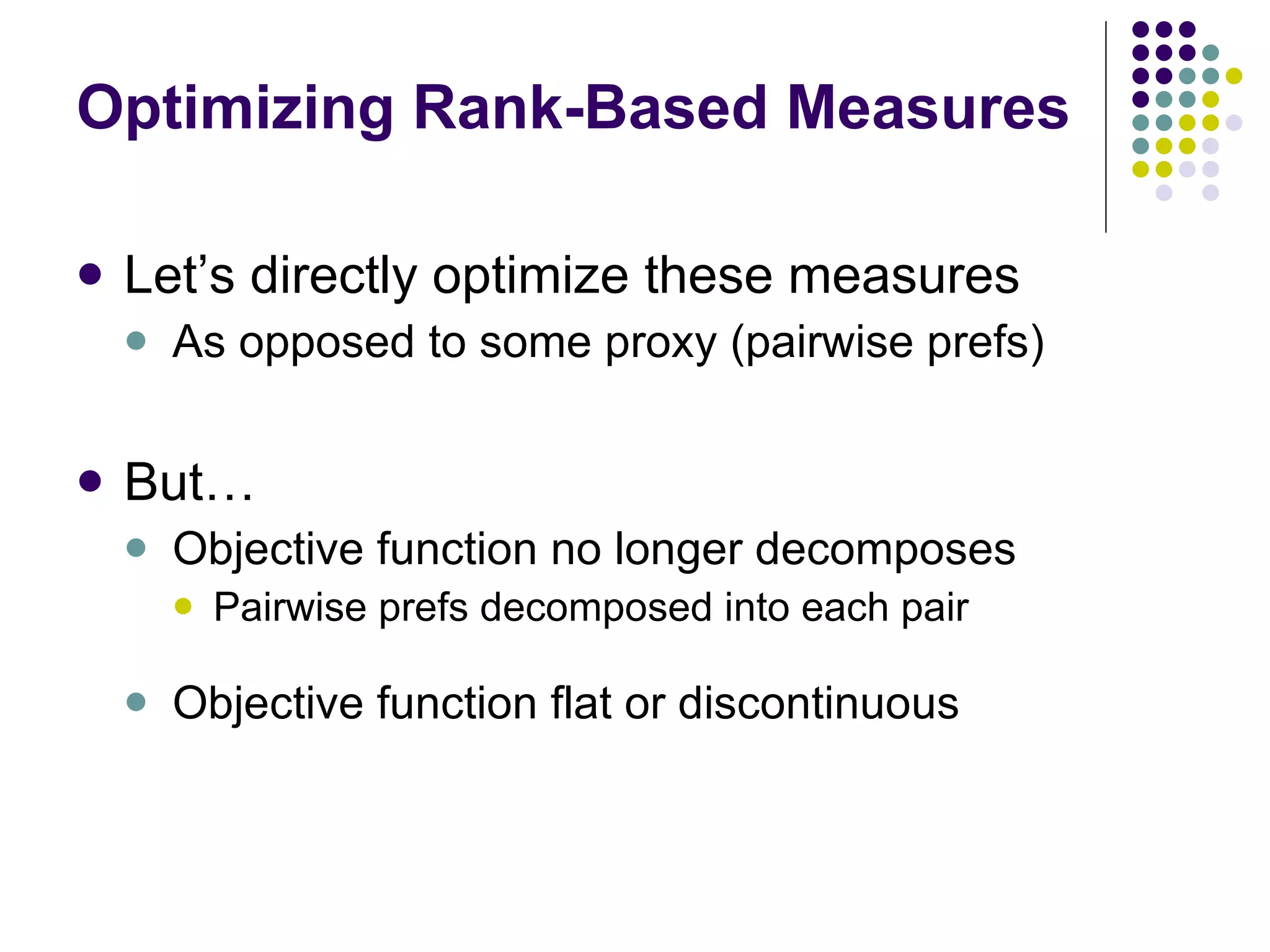

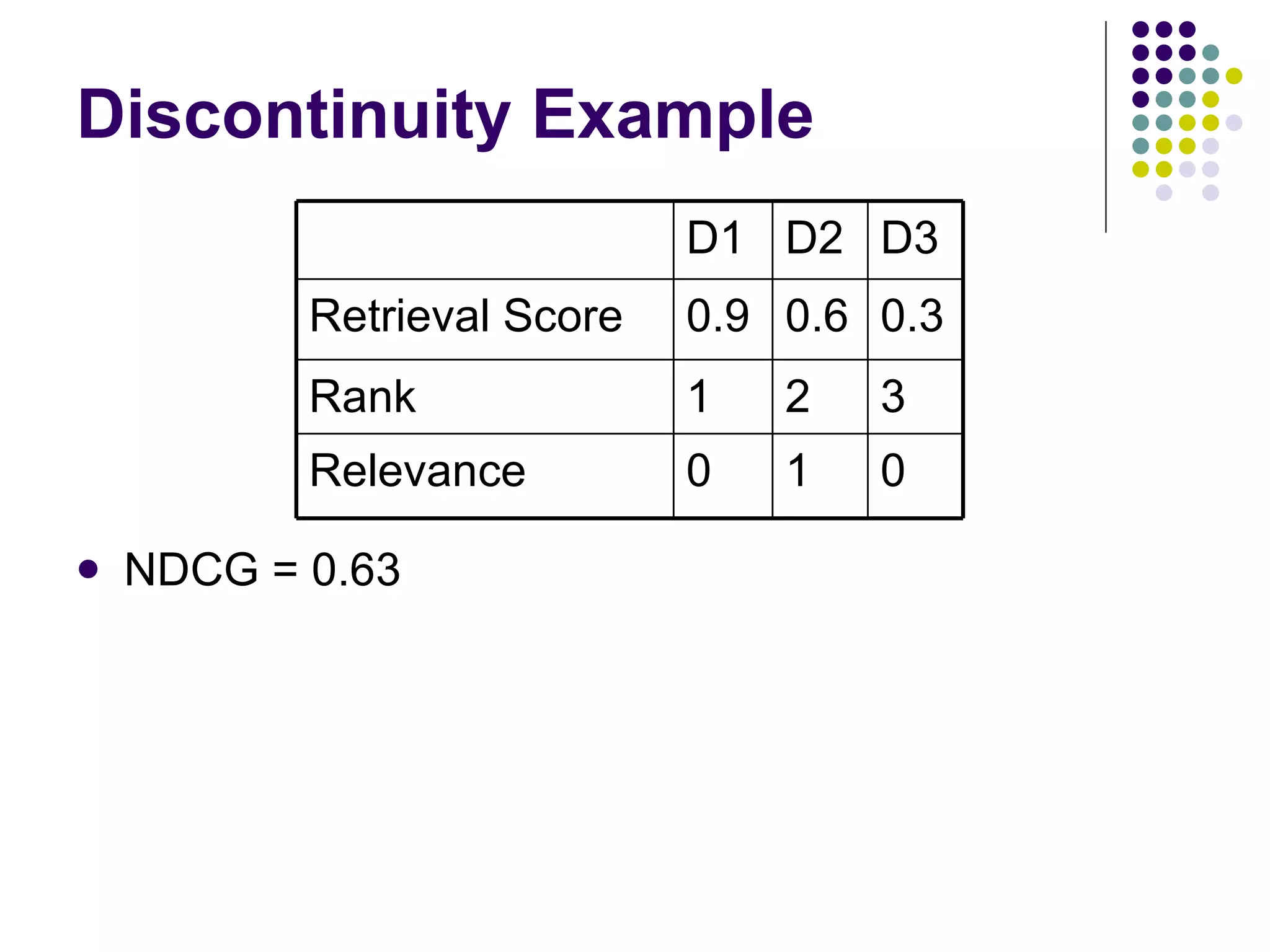

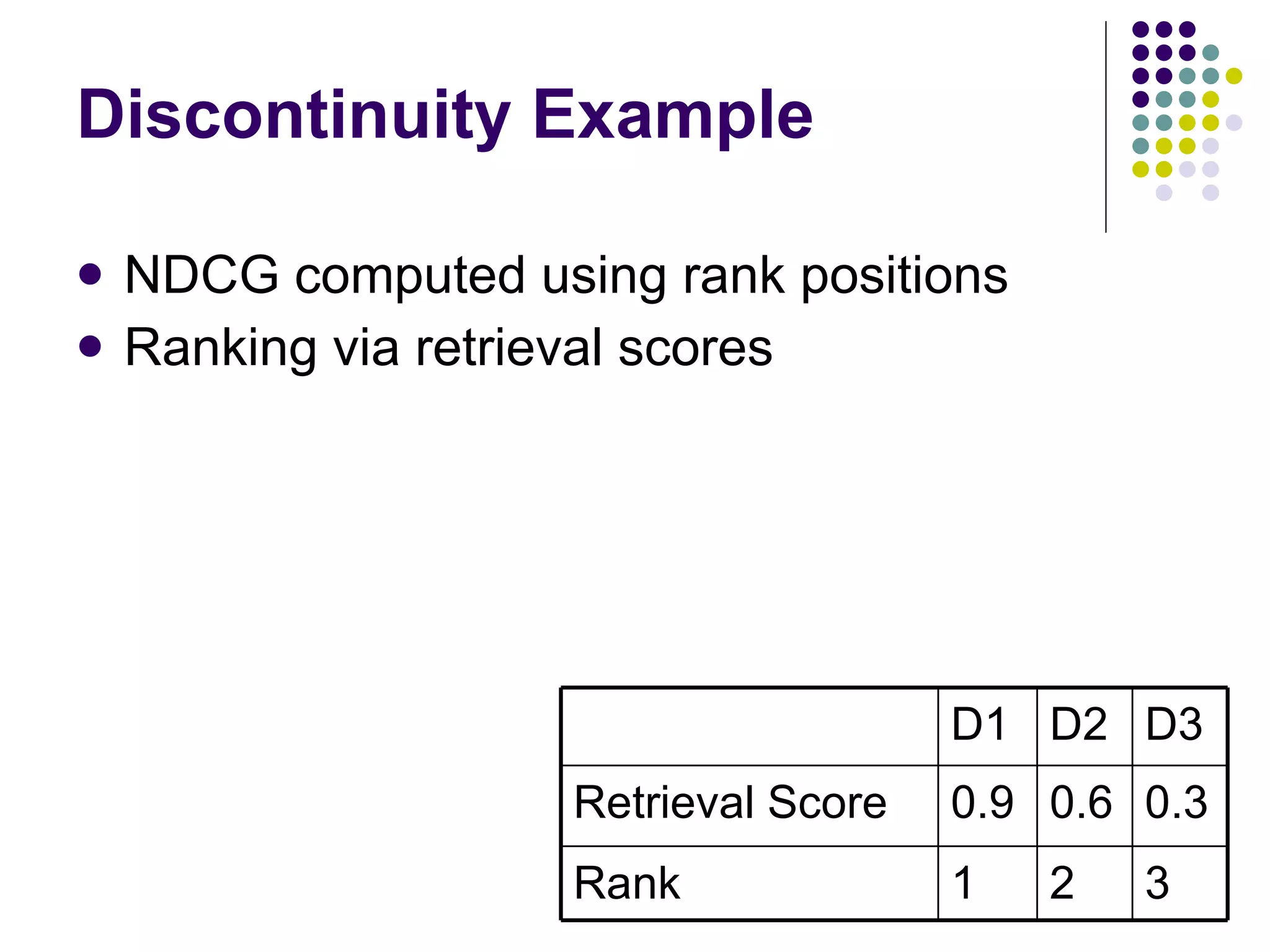

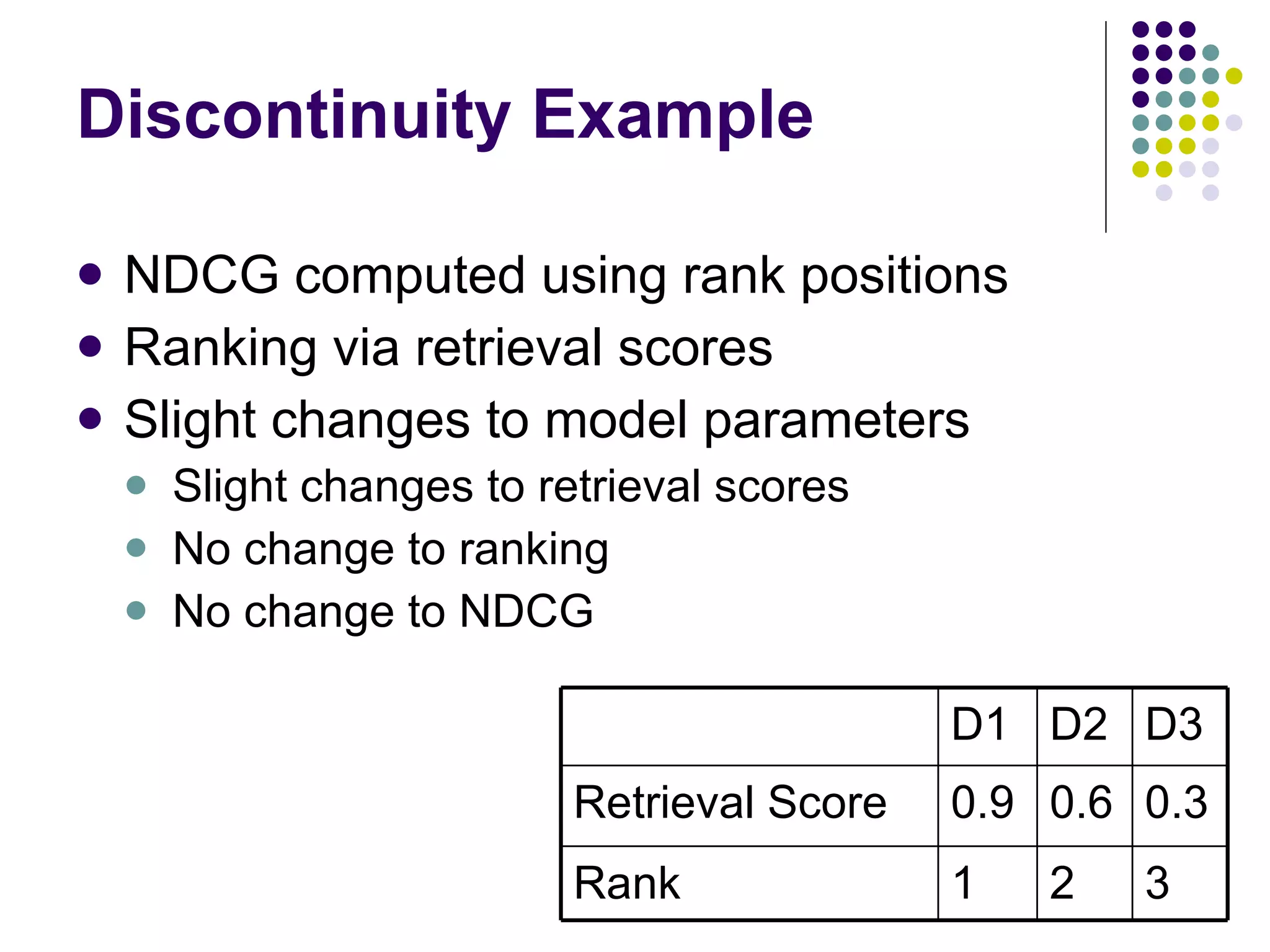

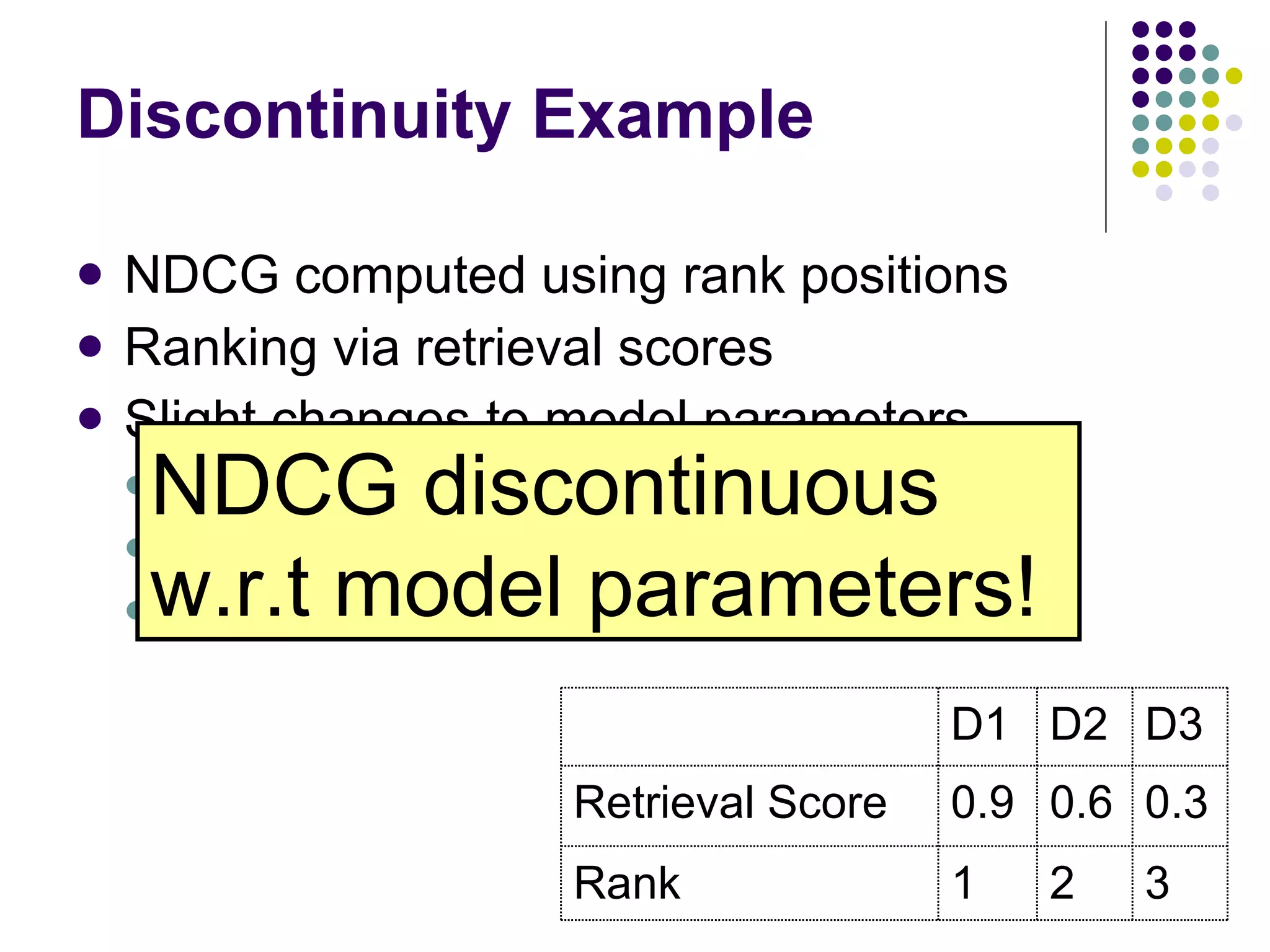

This tutorial covers machine learning approaches for learning to rank documents in information retrieval systems. It discusses how early IR methods did not incorporate machine learning. It then covers: (1) ordinal regression approaches that learn multiple thresholds to account for the ordered nature of relevance labels; (2) optimizing pairwise preferences between documents, which decomposes the problem and allows for efficient algorithms; (3) directly optimizing rank-based evaluation measures like MAP and NDCG using structural SVMs, boosting, or smooth approximations to allow for gradient descent optimization of discontinuous objectives. The goal is to outperform traditional IR methods by applying machine learning techniques to learn good ranking functions.

![Basic Approach to IR Given query q and set of docs d 1 , … d n Find documents relevant to q Typically expressed as a ranking on d 1 ,… d n Similarity measure sim(a,b) ! R Sort by sim(q,d i ) Optimal if relevance of documents are independent. [Robertson, 1977]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-11-2048.jpg)

![Other Methods TF-IDF [Salton & Buckley, 1988] Okapi BM25 [Robertson et al., 1995] Language Models [Ponte & Croft, 1998] [Zhai & Lafferty, 2001]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-14-2048.jpg)

![Ordinal SVM Example [Chu & Keerthi, 2005]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-27-2048.jpg)

![Ordinal SVM Formulation Such that for j = 0..T : [Chu & Keerthi, 2005] And also:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-28-2048.jpg)

![Learning Multiple Thresholds Gaussian Processes [Chu & Ghahramani, 2005] Decision Trees [Kramer et al., 2001] Neural Nets RankProp [Caruana et al., 1996] SVMs & Perceptrons PRank [Crammer & Singer, 2001] [Chu & Keerthi, 2005]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-29-2048.jpg)

![Option 2: Voting Classifiers Use T different training sets Classifier 1 predicts 0 vs 1,2,…T Classifier 2 predicts 0,1 vs 2,3,…T … Classifier T predicts 0,1,…,T-1 vs T Final prediction is combination E.g., sum of predictions Recent work McRank [Li et al., 2007] [Qin et al., 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-30-2048.jpg)

![Pairwise SVM Formulation Such that: [Herbrich et al., 1999] Can be reduced to time [Joachims, 2005].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-37-2048.jpg)

![Optimizing Pairwise Preferences Neural Nets RankNet [Burges et al., 2005] Boosting & Hedge-Style Methods [Cohen et al., 1998] RankBoost [Freund et al., 2003] [Long & Servidio, 2007] SVMs [Herbrich et al., 1999] SVM-perf [Joachims, 2005] [Cao et al., 2006]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-38-2048.jpg)

![[email_address] Set a rank threshold K Compute % relevant in top K Ignores documents ranked lower than K Ex: Prec@3 of 2/3 Prec@4 of 2/4 Prec@5 of 3/5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-41-2048.jpg)

![[Yue & Burges, 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-50-2048.jpg)

![Optimizing Rank-Based Measures Relaxed Upper Bound Structural SVMs for hinge loss relaxation SVM-map [Yue et al., 2007] [Chapelle et al., 2007] Boosting for exponential loss relaxation [Zheng et al., 2007] AdaRank [Xu et al., 2007] Smooth Approximations for Gradient Descent LambdaRank [Burges et al., 2006] SoftRank GP [Snelson & Guiver, 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-51-2048.jpg)

![Structural SVMs Let x denote the set of documents/query examples for a query Let y denote a (weak) ranking Same objective function: Constraints are defined for each incorrect labeling y’ over the set of documents x. After learning w, a prediction is made by sorting on w T x i [Tsochantaridis et al., 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-52-2048.jpg)

![Structural SVMs for MAP Maximize subject to where ( y ij = {-1, +1} ) and Sum of slacks upper bound MAP loss. [Yue et al., 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-53-2048.jpg)

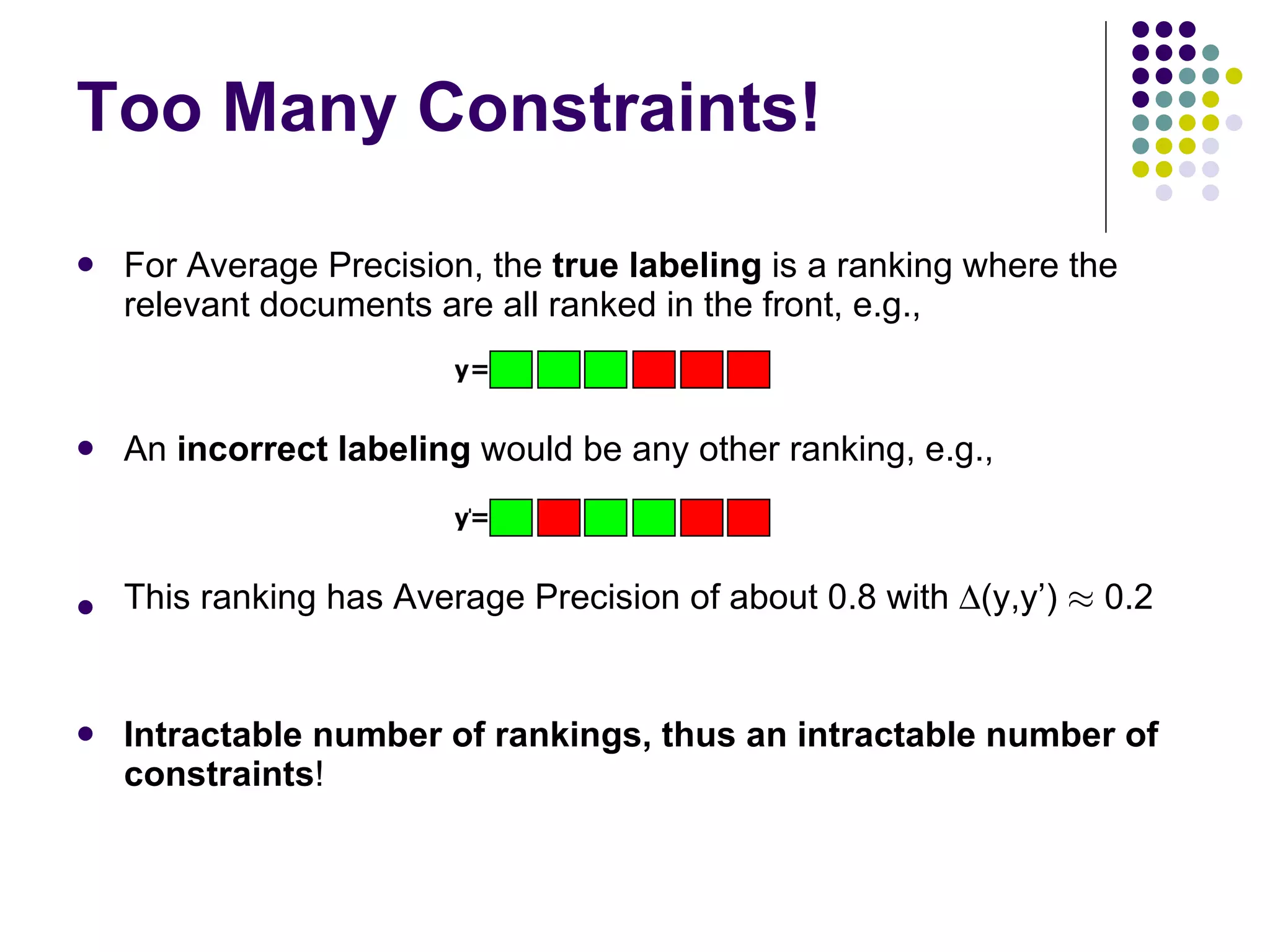

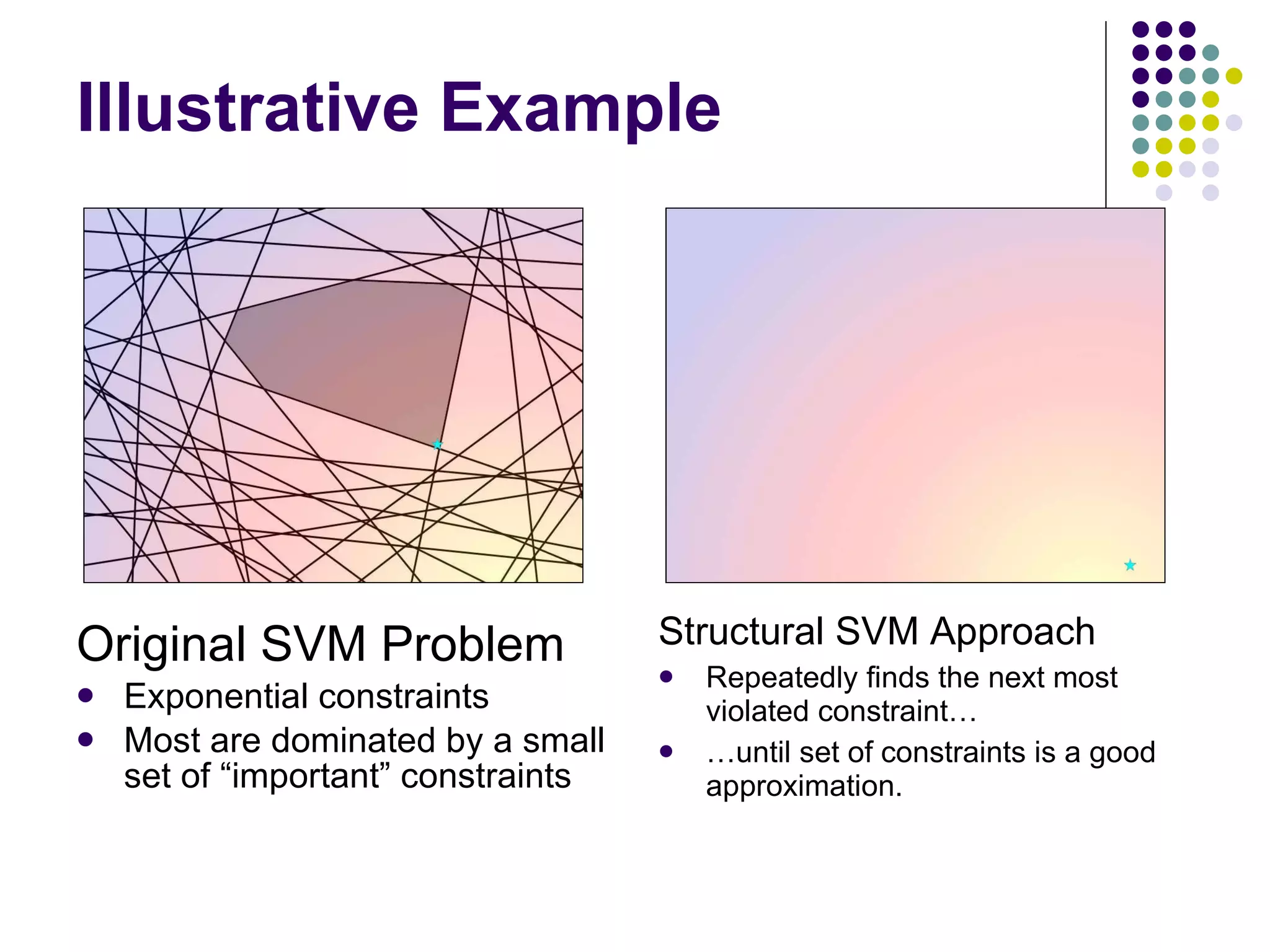

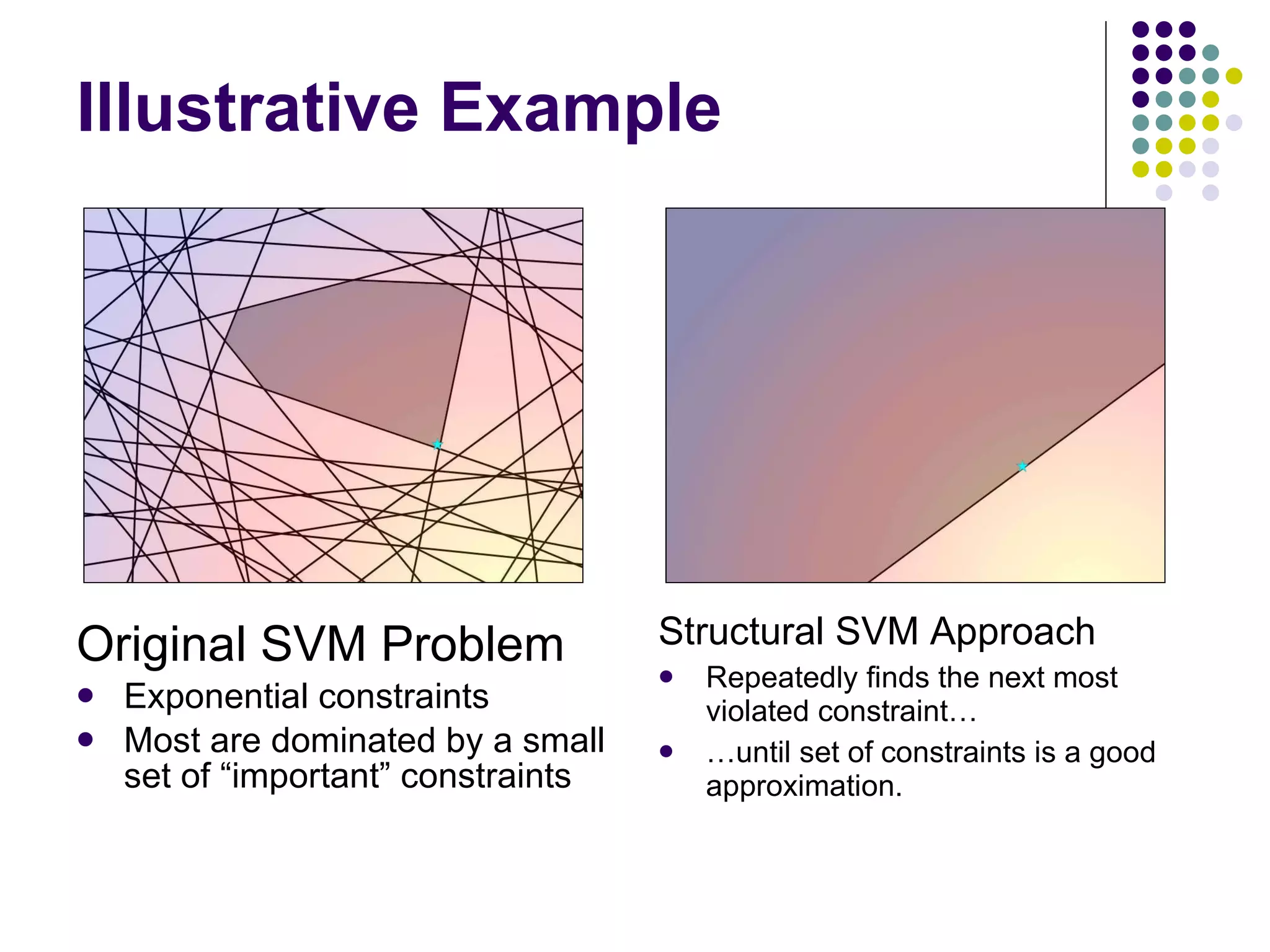

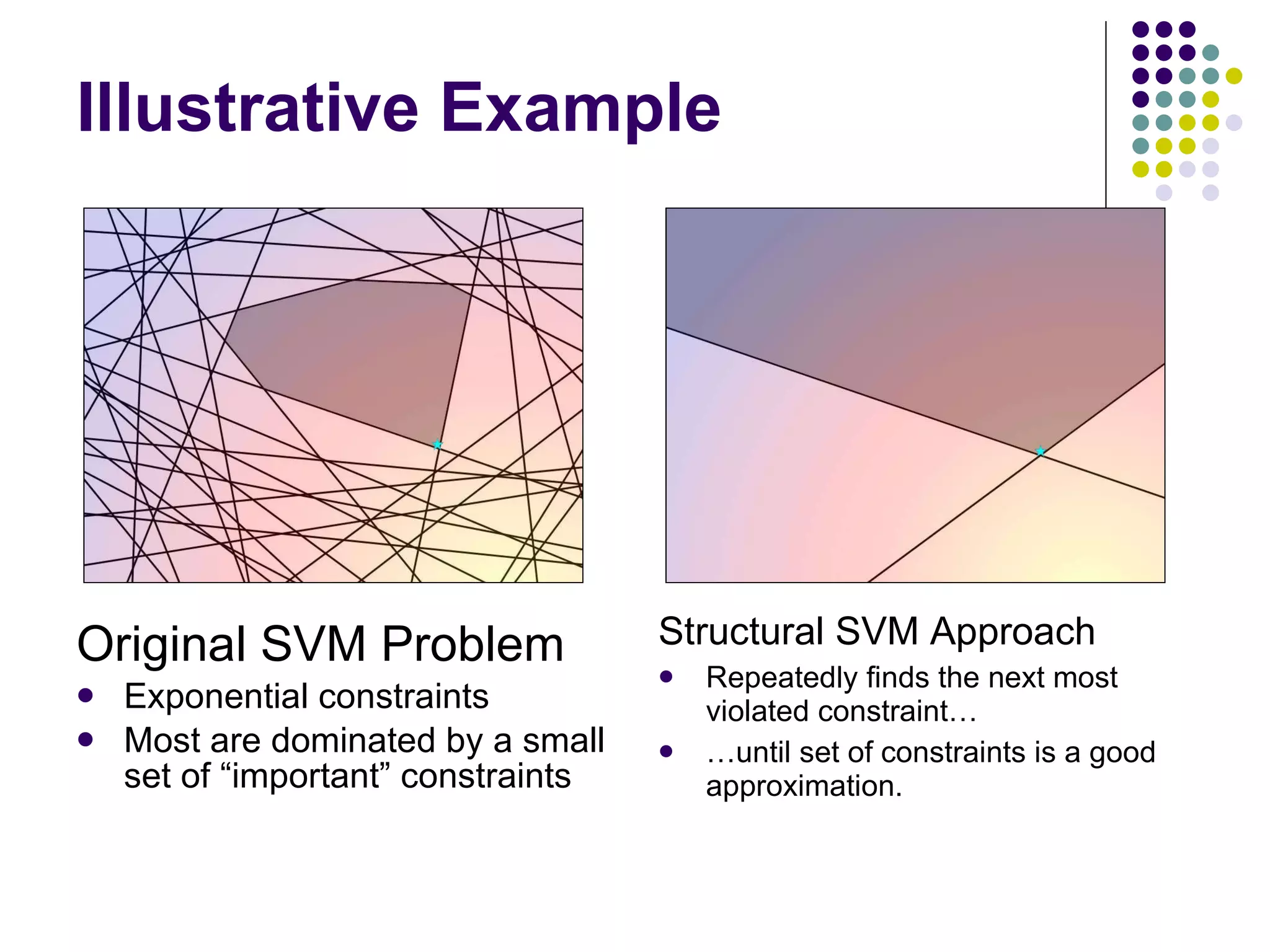

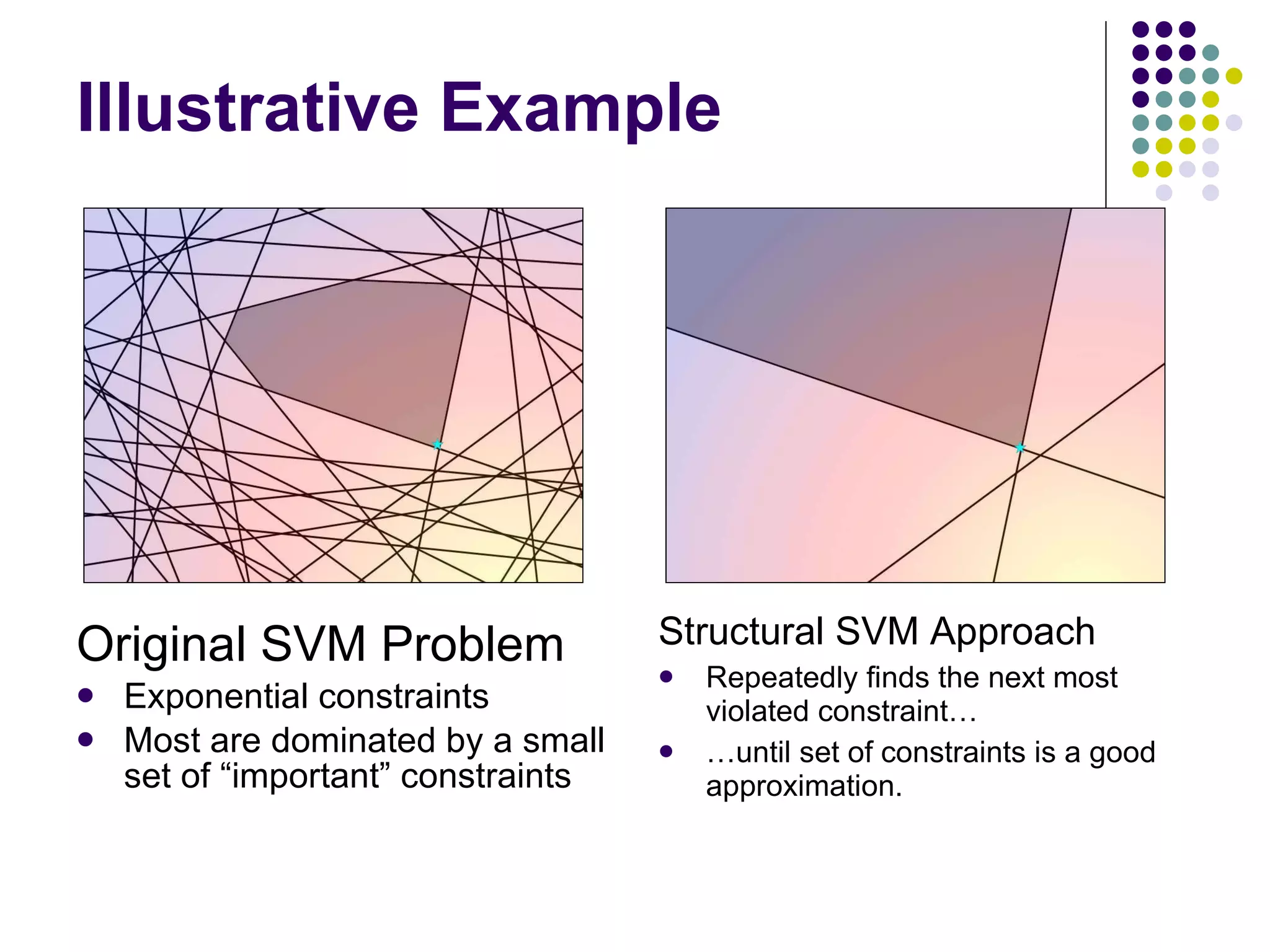

![Structural SVM Training STEP 1: Solve the SVM objective function using only the current working set of constraints. STEP 2: Using the model learned in STEP 1, find the most violated constraint from the exponential set of constraints. STEP 3: If the constraint returned in STEP 2 is more violated than the most violated constraint the working set by some small constant, add that constraint to the working set. Repeat STEP 1-3 until no additional constraints are added. Return the most recent model that was trained in STEP 1. STEP 1-3 is guaranteed to loop for at most a polynomial number of iterations. [Tsochantaridis et al., 2005]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-55-2048.jpg)

![Finding Most Violated Constraint Required for structural SVM training Depends on structure of loss function Depends on structure of joint discriminant Efficient algorithms exist despite intractable number of constraints. More than one approach [Yue et al., 2007] [Chapelle et al., 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-60-2048.jpg)

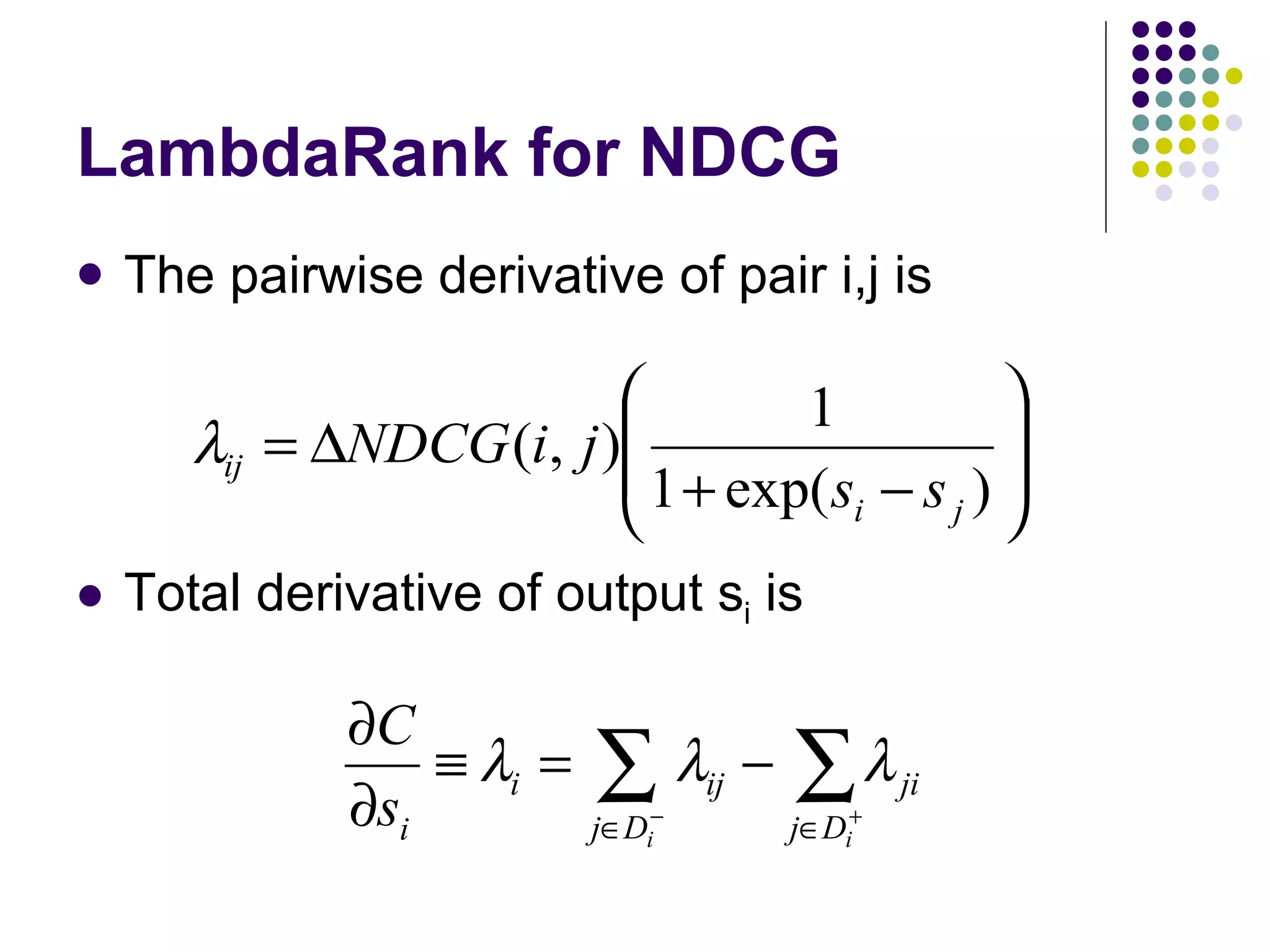

![LambdaRank Assume implicit objective function C Goal: compute dC/ds i s i = f(x i ) denotes score of document x i Given gradient on document scores Use chain rule to compute gradient on model parameters (of f) [Burges et al., 2006]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-62-2048.jpg)

![Intuition: Rank-based measures emphasize top of ranking Higher ranked docs should have larger derivatives (Red Arrows) Optimizing pairwise preferences emphasize bottom of ranking (Black Arrows) [Burges, 2007]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-63-2048.jpg)

![Properties of LambdaRank 1 There exists a cost function C if Amounts to the Hessian of C being symmetric If Hessian also positive semi-definite, then C is convex. 1 Subject to additional assumptions – see [Burges et al., 2006]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/part-12354/75/Part-1-65-2048.jpg)