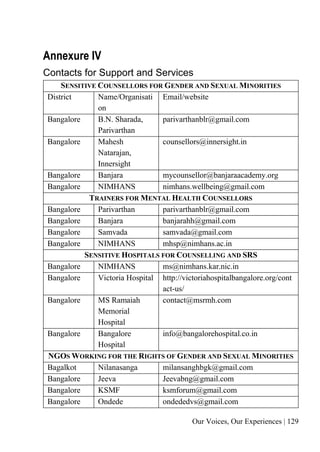

The document outlines the first edition of 'Our Voices, Our Experiences,' published by Jeeva, a community organization focused on supporting transgender individuals in Karnataka. It compiles personal stories and experiences of transgender people, highlighting their struggles, challenges, and victories, alongside discussions of engagements with law and society. The book aims to foster awareness and dialogue about the issues faced by gender and sexual minorities.

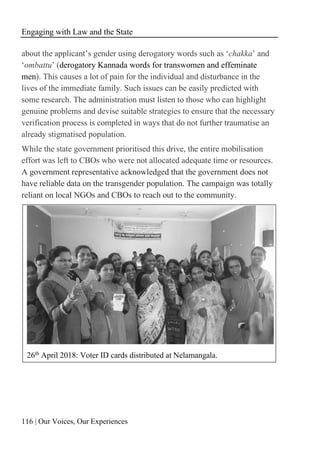

![Our Voices, Our Experiences

32 | Our Voices, Our Experiences

what I wanted to express. I was very happy I met him. I shared all my

feelings with him and we became best friends.

We faced a lot of problems in college because we wore pants and shirts.

Many of the other students’ parents started complaining that their children

were roaming around with two boys in the women’s college campus. The

complaints went to the principal. He was very confused trying to figure out

who these two boys were. The complaints became very serious and one day

the principal called us and insisted we bring our parents. The next day both

of us went to college with our parents. The principal asked my mother

strange and horrible questions: “Is your child male or female? Why does

she wear men’s clothing to college?” He asked me, “what organs do you

have?” He said that the college is for women and no male students are

allowed. My mother pleaded, telling him that I like to dress only in pants

and shirts. The principal scolded my mother and my friend’s parents, telling

them that they were not raising their daughters properly as we “behave like

boys, sing like boys and dress like boys. We [the college] will not let girls

wear pants and shirts. They must wear churidars or skirts”. We tried to

justify our dressing as we were not wearing skimpy clothes, we only wore

pants and shirts which covered the whole body. The principle said that girls

would get ‘spoiled’ because of us and the college name would be corrupted.

He instructed the teachers and students not to mingle with us because if

they did, they would also become like us. After that incident, nobody spoke

to us. We were ridiculed inside and outside the classroom. We were seen as

specimens. Though I was very interested in studies, I could not complete

my 12th

standard due to the harassment.

Battling alone

My mother was very unwell during this time and passed away. That was a

big blow for me. I ended up with living my relatives. They tried to change

everything about me, curtailed all my freedoms and pressurised me to get

married.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ourvoicesourexperiences2019-191006084435/85/Our-Voices-Our-Experiences-2019-41-320.jpg)