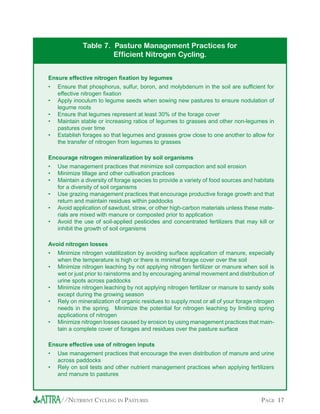

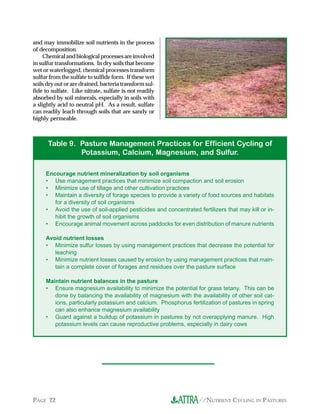

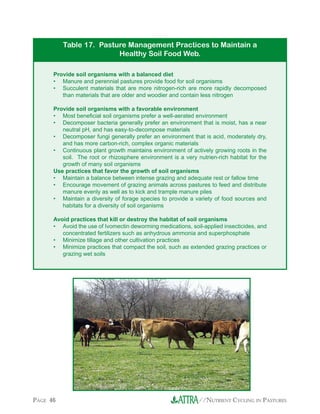

This document discusses nutrient cycling in pasture systems. It provides overviews of the water, carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and secondary nutrient cycles. Good pasture management practices can foster effective nutrient use and recycling. Specifically, managing pastures to enhance soil health, plant diversity, grazing intensity, and water quality can optimize forage and livestock growth while minimizing nutrient losses.