This document provides information about the copyright and committees for the proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge and Politics in Gender and Women's Studies 2015. It lists the scientific committee, advisory board, organizing committee, and student support team for the conference. It also provides copyright information, stating that abstracting and nonprofit use is permitted with credit, and instructors can print isolated articles for noncommercial use without fee. The document contains the conference committees, table of contents, and foreword for the proceedings.

![Anke Reichenbach / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 5

Western places that are more acceptable from a religious point of view, enjoy a wider popularity among

young Emirati women, such as art galleries, flea markets, non-chain coffee shops, second-hand bookstores,

or sports facilities. The young women often perceive such places as easy-going, permissive environments

where they can relax from the strict gendered norms of their own Emirati environments.

As clearly recognizable “outsiders”, however, they do not always feel entirely comfortable there.

Emirati friends told me that they were often openly stared at or photographed without permission, usually

by tourists who were thrilled to finally see an Emirati woman. Some Emiratis also felt that many expatriates

resented their presence in Western places, as if they were, as Amira put it, “a problem to come”. While

some Emiratis understand this unwelcoming attitude as postcolonial arrogance, others assume that

foreigners are simply afraid of unintentionally upsetting one of the supposedly all-powerful nationals and

having to face harsh consequences. Irrespective of the reasons, the occasionally annoyed reactions of

expatriates in “white” places make Emirati women sometimes feel “out of place” and not particularly

welcome.

3.3. “Emirati” places

In contrast to Dubai’s numerous non-Emirati territories, young Emirati women’s geographies of the city

contain only few places labeled as “Emirati”. Those include the luxurious Dubai Mall, especially on

weekends, a handful of smaller, elegant malls along the coast or near Emirati residential areas further inland,

and the newly opened entertainment and shopping districts Citywalk and Box Park. All “Emirati” places

share a number of characteristics: They are perceived as orderly, clean, safe and morally impeccable; they

are associated with an exclusive global culture of consumption, and they are privately owned, with security

staff, surveillance cameras and “courtesy policies” that discipline visitors’ behavior and dress. Similar to

the coffee shops explored by Lara Deeb and Mona Harb (2013) in Beirut, they thus “blur the borderline

between public and private spheres by domesticating public space” (2013: 27).

Most young Emirati women spend much of their leisure time in these places, mainly in the malls. There

they socialize with female friends, go to the movies, visit coffee shops and restaurants, stroll, or go

shopping. For them, malls are convenient and respectable places that considerably expand their access to

public urban space (cf. Abaza 2001, Akçaoǧlu 2009, Le Renard 2015). As Najma explained, women’s

families assume that malls provide a protective environment for their daughters, sisters, or wives:

“Our parents think that malls are safe. […] With the malls, it’s the idea that they know where you are, and that you are locatable.

And that they know everyone, especially from the Emirati society which is very small, and they all know each other. Which means

that someone is going to be there who knows you, in a way. So, it’s so much safer.”

As Najma’s quote highlights, malls and other Emirati places are, on the one hand, places where the

young women can feel “at home”, but on the other hand, they are also the public arenas where young

women’s conduct and appearance are most closely monitored and judged by their own compatriots.

Through displays of socially desirable feminine behavior and decent but elegant dress, accessories, perfume

and make-up, young women have to uphold the good reputation and status of their families. Under the

scrutinizing gazes of other Emiratis who “love to judge and gossip,” young women need to demonstrate

time and again that they are “respectable young ladies” who obey the rules of their society, as Firiyal, one

of my friends, put it. In Emirati places, the boundaries between men and women are more strictly policed

than in other environments, and even the most adventurous of my interviewees told me they would not dare

to enter a place that was full of Emirati men, fearing harassment and gossip. Thus, “Emirati” places](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-19-320.jpg)

![Anke Reichenbach / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 6

constitute rather ambivalent environments for young national women: The places where they are among

their own compatriots also harbor the greatest risks for their reputations.

But even this intense social control cannot prevent young Emiratis from transgressing moral boundaries.

Many young women find the gender-mixed character of malls and other “Emirati” places tantalizing, since

only this kind of leisure environment offers the chance to playfully interact and flirt with Emirati men.

Fatma explained:

“We cannot have such interactions with men anywhere else. We have family gatherings, we have male cousins, but we cannot

just chitchat with them. It’s not good, it’s not decent. […] The eyes of the family are always on us, on the girls. You shouldn’t do

anything, you should be good, an angel, and you shouldn’t be naughty, you know. It’s nice to have a different kind of interaction

sometimes.”

Since this “different kind of interaction” between unrelated men and women is socially frowned upon,

however, it cannot take place in settings such as coffee shops or restaurants where accidental observers

could easily take notice. Instead, such clandestine interactions occur in the transit and passage zones of

“Emirati” territories, in interstices and on back-stages, where people keep on moving and encounters are

fleeting. While circulating through the malls’ passages, on their way through the malls’ car parks, or while

driving at night along well-known “flirt roads” such as Jumeirah Beach Road, Emirati men and women

exchange glances and smiles. They engage in playful banter and mutual teasing; young men approach

women with small gifts such as CDs with love songs, roses, or chocolates and attempt to persuade them to

accept their telephone numbers. Men and women pursue each other in their cars and interact from vehicle

to vehicle through half-open windows.

In such encounters, young Emiratis defy social norms and subvert the hierarchies of gender and

generation (cf. Wynn 1997). However, even during such fleeting encounters women need to protect their

reputation by remaining anonymous, e.g. by exchanging mobile numbers that are not registered in their

names, or by remaining half-hidden behind tinted car windows. “Nothing can bring shame on men,” a

popular proverb states. Young Emirati women’s reputations, however, are much more vulnerable, particular

in those public places where the women ostensibly belong.

4. Conclusion

Amira, the young woman quoted at the beginning, had emphasized her sense of being under constant

scrutiny in the public spaces of Dubai. As this paper has shown, other Emirati women share her sentiments

of being exposed to different kinds of judgement by various audiences in the city. While the places

categorized as “non-Emirati” appear to offer a respite from the gendered constraints prevalent in Emirati

environments, they are often also perceived as unwelcoming to Emirati nationals. “Emirati” places on the

other hand are viewed as safe, respectable and morally impeccable, but there, women experience the most

intense pressure to adhere to strict gendered norms. Hence, they harbor the greatest risks for a woman’s

reputation and social prospects. Yet, the assumption cherished by many families that “Emirati” places offer

no room for transgressions underestimates young women’s (and men’s) creativity and ingenuity in

subverting mechanisms of social control and appropriating public spaces for their own agendas. It is the

passages and transit zones of Emirati territories and thus mobility itself that enables young Emiratis to resist

scrutiny. But even in such fleeting encounters, young women bear the greater risks since it is their

compatriots’ moral judgement that, in the words of Najma, “can literally define your future.”

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Carla Bethmann for inspiring discussions and her insightful and critical comments on an

earlier version of this paper.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-20-320.jpg)

![Anke Reichenbach / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 7

References

Abaza, Mona (2001) Shopping Malls, Consumer Culture and the Reshaping of Public Space in Egypt.

Theory, Culture & Society 18/5: 97-122.

Afsaruddin, Asma (1999) Introduction: The Hermeneutics of Gendered Space and Discourse. In: Asma

Afsaruddin (ed.) Hermeneutics and Honor. Negotiating Female “Public” Space in Islamic/ate Societies.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1-28.

Akçaoǧlu, Aksu (2009) The Shopping Mall. The Enchanted Part of a Disenchanted City. The Case of

ANKAmall, Ankara. In: Johanna Pink (ed.) Muslim Societies in the Age of Mass Consumption. Politics,

Culture and Identity between the Local and Global. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 53-72.

Bianca, Stefano (1991) Hofhaus und Paradiesgarten. Architektur und Lebensformen in der islamischen

Welt. [Courtyard House and Paradise Garden. Architecture and Lifestyles in the Muslim World]. Munich:

C. H. Beck.

Bristol-Rhys, Jane (2012) Socio-spatial Boundaries in Abu Dhabi. In: Mehran Kamrava & Zahra Babar

(eds.) Migrant Labor in the Persian Gulf. London: Hurst & Company, 59-84.

Dahlgren, Susanne (2010) Contesting Realities. The Public Sphere and Morality in Southern Yemen.

Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Davidson, Christopher M. (2008) Dubai: The Vulnerability of Success. New York: Columbia University

Press.

Deeb, Lara (2006) An Enchanted Modern. Gender and Public Piety in Shi’i Lebanon. Princeton:

Princeton University Press.

Deeb, Lara & Mona Harb (2013) Leisurely Islam. Negotiating Geography and Morality in Shiʻite South

Beirut. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

De Koning, Anouk (2009) Gender, Public Space and Social Segregation in Cairo: Of Taxi Drivers,

Prostitutes and Professional Women. Antipode 41/3: 533-556.

El Guindi, Fadwa (1999) Veil. Modesty, Privacy and Resistance. Oxford: Berg.

Holmes-Eber, Paula (2003) Daughters of Tunis. Women, Family, and Networks in a Muslim City.

Boulder: Westview Press.

Kanna, Ahmed (2011) Dubai. The City as Corporation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Kanna, Ahmed (2013) “A Group of Like-Minded Lads in Heaven”: Everydayness and the Production of

Dubai Space. Journal of Urban Affairs 36/S2: 605-620.

Kapchan, Deborah (1996) Gender on the Market. Moroccan Women and the Revoicing of Tradition.

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Lee, HongJu & Dipak Jain (2009) Dubai’s brand assessment success and failure in brand management –

Part 1. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 5/3: 234-246.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-21-320.jpg)

![Aslı Polatdemir and Charlotte Binder / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 30

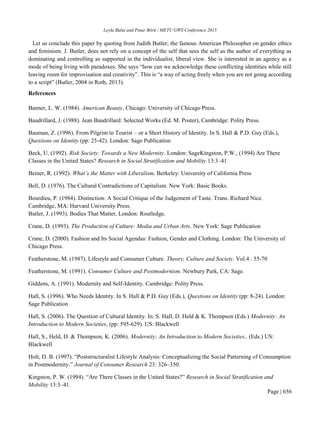

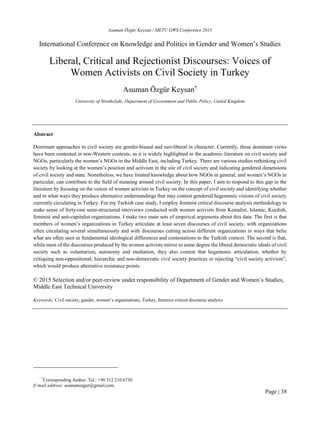

Table 1. Information about conducted interviews

Cities Ankara Diyarbakır Aegean Region

(Denizli, Muğla)

East Black Sea Region

(Trabzon, Artvin)

Period of field

research

03.-04.2014;

09.-10.2014

03.-04.2014;

04.2015

03.-04.2015 06.-07.2015

Number of

conducted

interviews

20 9 18 18

2.1. Topic of research: diversity of women’s movements

The universal category of gender is a topic which is open to discussion in poststructural, (queer-) feminist

and postcolonial theory, as well as in the identity politics put forward by new social movements. In the

process of social-constructivist transition in Women’s and Gender Studies, the up-to-now collectivist

aspects of women’s movements were questioned (Lenz 2002: 78).

Aside from exploring coalitions and solidarity in women’s movements in Turkey, this project also puts

special emphasis on the integration of this diversity aspect in its research scope. Thus, it is of importance

to discuss the project’s title. Due to reflection of universal debates on collective subjects of women’s

movements, we decided to apply a feminist-oriented social movement research theory, which

conceptualises women’s movements as plural-differentiated and transnationally oriented (Lenz 2014).

While putting an ‘-s’ at the end of women’s movement and feminism, we, as the members of research

project, do aim to include diverse perspectives. Even if the analysis of our interview material is in an early

stage, our first findings could shed light on the specific area which we are targeting. If interviewees have

different positions on certain topics, this plural ‘-s’ plays an important role and it needs to be emphasised.

İlknur Üstün, coodinator of the Women’s Coalition in Ankara, underlines the necessity of touching upon

the topic with special awareness:

[…] it is important to recognize the diversity, it is a dynamic structure, in all of these

diversities, differences it would not be fair to lump them together […]it is necessary to talk

about a process when you talk about woman, women’s movement or movements in Turkey.

(İlknur Üstün 2014)

Violence against women and the ruling government’s misogyny lead to the development of spaces and

platforms for coalitions and solidarity, as Gaye Cön, member of the woman centre KAMER from Muğla,

points out: “Because each passing day there are more attacks against woman by the government, we often

come together there, that is to say if I think about Turkey in general.” (Gaye Cön 2014)

However, the beauty of the matter lies not merely in that solidarity should always be pursued, or that

coalitions should be formed for everything, but rather in the colourful mosaic of different groups attempting

to work together to effect social change. Bahar Bostan, member of the Women’s Rights Commission of

Trabzon Chamber of Lawyers, aptly describes it in the following passage:

Islamist women, Kurdish women, Turkish women - like socialist feminists, Turkish

Women’s Association - we all unite. Especially in case of the state’s invasion of our spaces.

However, when human rights and ethnic issues are on the table, or political matters, or

political differences, we go our separate ways. Well, when we analyse this as Kurdish](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-44-320.jpg)

![Aslı Polatdemir and Charlotte Binder / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 31

Women’s Movement, Turkish Women’s Movement or Secular Women’s Movement, Islamist

Women’s Movement, we disintegrate. (Bahar Bostan 2015)

Nebahat Akkoç, founder of KAMER and based in Diyarbakır, comments on the intersectional perspective

and discusses the interdependent character of women’s issues in the country:

[…] the main issue in Turkey is still the existence of prejudices and discrimination; I have

the impression it is about a lack of clear decisions on whether we want to be on the side of

the leading power, or whether we want to remain independent […] we still cannot talk,

understand the woman issue as independent, abstracted from the system, as a disconnected

issue from other matters, so it remains disconnected. (Nebahat Akkoç 2015)

Interviewees, depending on what group they identify with, had diverse perspectives on, for instance,

LGBTI rights, sex work or education in their mother tongue. At this point, representation of diversity

remains the focal point of this research project.

2.2. Reflection of research: questions on representation

Postcolonial theorist Spivak (2008) underlines postcolonial criticisms of representation and knowledge

production of Eurocentric research. This research project aims to gain understanding by borrowing from

feminist and postcolonial theories in order to properly deal with the delicate matter of this “crisis of

representation” (Winter 2011: 76). This recognition of the (re-)construction of reality, knowledge

production and epistemic rupture are the leading framework for our approach in the analysis of the

interviews.

Said’s concept of othering and orientalism (1979) is very helpful when reflecting on the role of

researchers from Germany/Europe, and when exploring possible approaches in the fight for women’s

equality in Turkey. However, it cannot tell us much about the epistemic assimilation effects that can also

be observed. Thus, with reference to Spivak’s concept of epistemic rupture, we want to briefly explain what

we refer to when we speak of epistemic assimilation: when discussing the rupture between different

discourses, Spivak stresses that every discourse has its own language, its own narratives and its own rules.

Therefore, the forms of interaction in one discourse can be very different from those in another discourse.

Thus, what counts as adequate or as a good argument is very different in each of those discourses. Following

this approach, the planned report on women’s movements in Turkey has to avoid linear references to the

German/European discourse of gender struggle when interpreting developments in Turkey. Because when

Western epistemic categories are applied in the description of occurrences, it dismisses the discursive

properties of the culture this research is studying. To understand, but not to assimilate the activists in Turkey

to a German perspective, it is necessary to find out in which categories they are speaking of themselves in

order to grasp their self-understanding and their motivation. Taking this into consideration, our aim in the

final report is to move beyond orientalist views on women in Turkey, and paint a detailed and appropriate

picture of what it means to be a woman in Turkey, and what her struggles are.

How does our research team deal with the ‘crisis of representation’, both in theory and in practice?

Theory-wise we refer to the aforementioned postcolonial theory and critics of orientalism. This research

project was designed to be an empirical study, meaning attempts to bridge the gap between empirical

research and theory need to be refined with a special standpoint. The standpoint model of research was

developed by feminist social scientists in the late 80s (Harding 2004). In brief, various social positions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-45-320.jpg)

![Aslı Polatdemir and Charlotte Binder / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 33

How will we stand side by side? How will we stand as one? How will we recognize each

other’s different experiences and struggle for each other’s’ rights? How will we get

organized around our gendered identities with our ethnic, cultural, class-related, sexual,

regional, religious and bodily differences? (Bilal 2006)

This chain of questions, put forward by the Armenian feminist and academician Melissa Bilal, clarifies

why debates on the politics of solidarity, and on coalitions within the feminist movement happen, despite

their differences. Because of contributions from antiracist, antimilitarist and queer perspectives between

then and now, autonomous feminists aim to approach to Kurdish women and LGBTI groups. Their mutual

opponent, patriarchal structures are identified which oppress women, LGBTI individuals and members of

ethnic and religious minorities through sexism, heterosexism, racism and/or militarism (Acar Savran 2011).

An example of solidarity between feminists and religious-conservative women is the platform ’We stand

by one another’, which was established by female activists, journalists and academics as a reaction to the

headscarf debates in 2008. Women only partly affected by the headscarf ban, came together and insisted

that female students with a headscarf be freely allowed into university buildings, and thus protected from

discrimination based on gender and/or religious affiliation (Koç 2009).

However, because of their experiences within leftist movements in the 70s, many autonomous feminists

have only collaborated sparingly with leftist and Kemalist-oriented women (Somersan 2011: 100 – 123).

Despite all mutual concerns and the diversification process in the frame of historical steps of women’s

movements in the country, how could (im-)possibilities of solidarity and coalitions be put on the table while

there are endless responses and subjective concepts of “being-a-woman”?

4. (Im-)Possibility of coalitions despite of diverse reflections on “being-a-woman“?

There are many different responses to the interview question “Being a women - what does it mean to

you?”:

[…]we talk about a creature which maintains its life, contributes hugely to social

relations, but with its other part being oppressed, exploited, in other words like summation

of being subject and object. (Figen Aras 2015)

[…] she is in part a biological creature, with reproductive organs and breasts, but […]

being a woman means one has to carry lots of things together with place, culture and people

you live with. Both living its delightfulness but more struggle with its difficulties. (İlknur

Üstün 2014)

[…] being a woman is also something we learn about. [...] all cases of being woman, man

and so forth are speculative for me and personally my thing is, you know if the current

situation would not be like this, I would not emphasize my female identity, I would not make

women’s policy. In other words because it does not fit to my attitude, I love to define myself

as a woman as well as a man rather than only as woman or man. But actually you know I

insistently stress my woman identity because we live in a terrible state of society, surely I

believe it is necessary to struggle for this. (Pelin Kalkan 2014)

Since we have endless explanations of what being a woman even means, how can we even talk about

whether all women can fight together? Interviews conducted in 2014 and 2015, and literature analyses](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-47-320.jpg)

![Asuman Özgür Keysan / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 44

such relations arise from within civil society or between CSOs and the state. The anti-hierarchy discourse is

mainly discussed with regard to relationships within CSOs, and specifically the issue of representation and

leadership.

The critique of hierarchy dovetails for many of my interviewees with their critique of patriarchy. The

women activists from SELİS and KAMER certainly identified male dominance as one of the roots of

hierarchy. As Reşide, one of the youngest activists from SELİS, comments, “We grow up with this

hierarchical structure in which mother is always in the kitchen, is responsible for the child care and the father

works outside. It is all these little things we grow up with” (interview, May 22, 2012). The fact that

dominance in the family translates into dominance of men in mixed group decision-making processes in civil

society annoys these women, and is contrary to their equality-based understanding of civil society. In line

with this approach, the CSOs dominated by men and attributing traditional gender roles to women are called

into question as Reşide from SELİS articulates in the following extract: “…for example, in one of the

meetings I participated in, there were some women who can said that “if a woman does cleaning at home,

gets along well with her husband, she is not exposed to violence”...there are also civil society organisations

[that support this kind of idea]” (interview, May 22, 2012).

Differently, some interviewees from KA-DER and AMARGI emphasize that the transformation of civil

society can only be realised by feminism. While integrating a feminist approach into civil society is

acknowledged as being “difficult due to the dominance of hierarchies within and between the civil society

organisations” (interview with Çiçek, KA-DER, July 21, 2012), Duygu, one of the oldest members of

AMARGİ that I interviewed, argues that feminism has already had a significant impact on civil society. She

says that “it is feminism that will bring horizontal organisation into the society … and should develop

relationships with civil society” (interview, June 2, 2012).

3.2.3. Democratization discourse

The emphasis on the democratic outcomes of the promotion of civil society activism lies at the heart of

democratization discourse, which is circulated by the women from the KAMER, SELİS, US and KA-DER.

Nonetheless, these women activists from two different groups have different ideas about what the main goal

of democratization should be. Whereas almost all of women from KAMER and SELİS evoke a civil society

area free of discriminatory ideas and practices, women from US and KA-DER refer to a civil society space

which becomes more civil through the promotion of active-citizenship.

The interviewees from both Kurdish organisations focus their attention on the need for civil society to

combat discrimination. They frame discrimination between and within CSOs as a “democratic failure”, and

their emphasis upon it is linked to the regional and ethnic problems they encounter as Kurdish women and as

individuals working within Kurdish women’s organisations. In the first place, they argue that they face

discrimination on the basis of ethnic difference coded in geographical terms. Thus Nuray from KAMER

mentions that she is bothered by some people from other organisations referring to her as “coming from the

Eastern part of Turkey” (interview, May 16, 2012), i.e. the Kurdish regions of Eastern and South-Eastern

Anatolia. As noted by Derya from KAMER: “One of the problematic areas in the civil society is

discrimination … We can see it when we go to the West from the East [of Turkey] for project work. When I

say I am from Diyarbakır [a city in Eastern Anatolia], you can see eyebrows are raised, because they have

some type of profile in their minds, and they get surprised if the person they met doesn’t fit into this profile....”

(interview, May 17, 2012). For Derya, this discrimination can even result in violence: she goes on to describe

a Women’s Shelter Congress held in 2012 in which “Our women friends coming from the East and South-

East were almost lynched, they had to be guarded and sent away after they felt their lives were in danger …

This is ridiculous … This is where we are in civil society” (interview, May 17, 2012). Unlike the women](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-58-320.jpg)

![Aysel Arslan / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 78

1. Introduction

When I mention to people that I research gender in the Neolithic period, the period when people first

settled down and decided to do agriculture, most of the time I get questions about matriarchy and the Mother

Goddess. The idea of a society ruled by women and the Mother Goddess seems to be still attracting a lot of

attention by the public. The public interest in gender-related issues in the past communities mainly revolves

around the power relations between males and females. But, how do we understand who was ‘wearing the

pants’ in the society if they are long gone? Archaeologists have an answer to this question.

In this paper, I first provide a historical background to gender archaeology and thereafter elaborate on the

use of bioarchaeological studies when considering gender. Bioarchaeology is one of the main sources of a

gendered approach since human body gives archaeologists a great amount of information about how people

lived, what they ate, and what they did regularly. This way it becomes easier to make assumptions about

gendered lifeways in earlier periods.

After that, I discuss figurine analysis and its impacts on gender archaeology. I especially examine the

mother goddess theory that dominated the archaeological interpretation of female figurines until the 1980s.

This theory has been disputed by many scholars (eg. Fleming 1969; Tringham and Conkey 1998), yet there

is still a contingent who supports this idea and proposes that women’s ritual power and importance in the

society stems from their biological roles as birth givers (eg. Roller 1999). Finally, I summarize my

interpretations of the changing gendered lifeways in Central Anatolia from 8500 to 5000 BC as a case study.

2. The History of Gender Archaeology

Anthropological studies that concentrate on women, power and early states started as early as the 1970s

and it became clear that it was necessary to understand women in ancient history in order to understand

women’s roles in history (Hutson et al. 2013: 45). Archaeological research on gender and sexuality developed

thereafter in the 1980s (Conkey and Spector 1984; Voss 2000: 181; Spencer-Wood 2000: 113; Spector 1996:

485).

However, gender theory in archaeology and anthropology, as in other fields of the social sciences, take

their roots from much earlier theories. The origins of the discussion go back to the hypothesis in Engels’

1884 book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. Influenced by the post- enlightenment

theories, Morgan, and Bachofen, Engels proposed that there is a steady social development in human

evolution, and matrilineal and matriarchal societies were the original but the earliest social organizations

(Engels 1997[1884]: 12). He (1997[1884]: 14) discusses that in the earliest period of human civilization not

fathers, but mothers were highly esteemed because it was not possible to determine the biological father.

However, with the increase of wealth, men became more important than women in the family. He says “The

overthrow of mother right was the world historic defeat of the female sex.” (Engels 1997[1884]: 14, italics

in the original). With the appearance of monogamy, the first division of labor (childbearing), and the first

class oppression by males onto the females began (Engels 1997[1884]: 16).

In the 1970s, the feminist movement in anthropology and archaeology gained pace. In 1984, Conkey and

Spector wrote ‘Archaeology and the Study of Gender’, underlining that there is androcentrism in

archaeological and ethnological research. They criticized the archaeological approach to female roles as

females are less visible and regarded as separate from males (Conkey and Spector 1984: 6). It was generally

accepted that universal laws of behavior dictated male and female roles and relationships. In many cases,

although archaeologists did not think of women and gender, they were making assumptions or claims about

their roles and positions in prehistoric societies. While making these assumptions, they made use of western](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-92-320.jpg)

![Aysel Arslan / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 84

--- “Figurines, Corporeality, and the Origins of the Gendered Body.” A Companion to Gender

Prehistory. Ed. Diane Bolger. Pondicherry, India: Wiley and Blackwell, 2013: 244-264. Print.

Bolger, Diane. “Introduction: Gender Prehistory – The Story So Far.” A Companion to Gender Prehistory.

Ed. Diane Bolger. Pondicherry, India: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013: 1-19. Print.

Borić, Dušan, and T. Douglas Price. “Strontium isotopes document greater human mobility at the start of

the Balkan Neolithic.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110.9, 2013: 3298-3303. Print.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Outline of a Theory of Practice. Trans. R. Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1977. Print.

Butler, Judith. Gender trouble and the subversion of identity. New York and London: Routledge, 1990.

Print.

--- Bodies that matter: on the discursive limits of "sex". New York: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Conkey, Margaret W., and Janet D. Spector. “Archaeology and the study of gender.” Advances in

archaeological method and theory 7, 1984: 1-38. Print.

Düring, Bleda S. “Cultural Dynamics of the Central Anatolian Neolithic: the Early Ceramic Neolithic –

Late Ceramic Neolithic Transition.” The Neolithic of Central Anatolia: Internal Developments and

External Relations during the 9th–6th Millennia cal. BC. Proceedings of the International CANew Table

Ronde. Ed. F. Gerard and L. Thissen. Istanbul, Turkey: Ege Yayınları, 2002: 219-236. Print.

Engels, Friedrich. “The origin of the family, private property, and the state”, In: R.C. Tucker (ed.) The

Marx-Engels Reader, W.W. Norton and Company, New York, 1978[1884]: 734-759. Print.

Fleming, Andrew. “The myth of the mother‐goddess.” World Archaeology 1.2, 1969: 247-261. JSTOR.

Web. 15 Feb. 2014.

Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality, Volume I. New York: Vintage, 1978. Print.

Garcia-Ventura, Agnès. “From Engendering to Ungendering: Revisiting the Analyses of Ancient Near

Eastern Scenes of Textile Production.” Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology

of the Ancient Near East Vol. 3. Fieldwork & Recent Research Posters. Eds. Roger Matthews and John

Curtis. Harrasowitz: Wiesbaden, 2012: 505-515. Print.

Gilchrist, Roberta. Gender and Archaeology: Contesting the Past, London and New York: Routledge,

1999. EBSCOhost. Web. 16 March 2013.

Gimbutas, Marija Alseikaitė. The goddesses and gods of Old Europe, 6500-3500 BC, myths and cult

images. Univ of California Press, 1982. Print.

Hamilton, N., J. Marcus, G. Haaland, R. Haaland, and P.J. Ucko. “Viewpoint: Can we interpret figurines?”

Cambridge Archaeological Journal 6.2, 1996. 281-307. Cambridge Journals. Web. 11 May 2013.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-98-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Abbasoğlu-Özgören, Banu Ergöçmen, Aysıt Tansel / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 96

Acknowledgements

This paper forms a part of the PhD thesis of Ayşe Abbasoğlu-Özgören prepared under the supervision of Banu

Ergöçmen and Aysıt Tansel. A major empirical part of the thesis was carried out during a research visit of Ms.

Abbasoğlu-Özgören at Stockholm University Demography Unit (SUDA) funded by the scholarship from

TUBITAK with 2214/A International Doctoral Research Fellowship. She is grateful to TUBITAK for the support,

SUDA for their hospitality and Gunnar Andersson for his technical supervision.

References

Abbasoğlu, A. (2009). Investigating the Causality between Female Labour Force Participation and Fertility in

Turkey (Unpublished master’s thesis). HUIPS, Ankara.

Concepcion, M. B. (1974). Female Labor Force Participation and Fertility. International Labor Review,

109(5/6), 503‐517.

Hossain, M., & Tisdell, C. (2005). Fertility and female labour force participation in Bangladesh: Causality and

cointegration. Asian-African Journal of Economics and Econometrics, 5(1), 67-82.

İsvan, N. A. (1991). Productive and Reproductive Decisions in Turkey: The Role of Domestic Bargaining.

Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 1057-1070.

Ma, L. (2013). Employment and motherhood entry in South Korea, 1978-2003. Population-E, 68(3): 419-446.

Mason, K. O., & Palan, V. T. (1981). Female Employment and Fertility in Peninsular Malaysia: The Maternal

Role Incompatibility Hypothesis Reconsidered. Demography, 18(4), 549-575.

Narayan, P. K., & Smyth, R. (2006). Female labour force participation, fertility and infant mortality in

Australia: Some empirical evidence from Granger causality tests. Applied Economics, 38(5), 563-572.

Özdemir, D., & Dündar, H. Ç. (2012). Türkiye’nin Kriz Sonrası Eve Dönen Kadınları: İşgücüne Katılımda Kriz

Etkisi ve Fırsat Maliyeti. TEPAV Değerlendirme Notu, Ağustos2012 N201240.

Sevinç, O. (2011). Effect of Fertility on Female Labor Supply in Turkey (Unpublished master’s thesis). Middle

East Technical University, Department of Economics, Ankara.

Stycos, J. M., & Weller, R. H. (1967). Female Working Roles and Fertility. Demography, 4(1), 210-217.

Şengül, S., & Kıral, G. (2006). Türkiye’de Kadının İşgücü Pazarına Katılım ve Doğurganlık Kararları [Female

Labor Force Participation and Fertility Decisions of Women in Turkey]. T.C. Atatürk Üniversitesi Journal of

Economics and Administrative Sciences, 20(1), 89-104.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-110-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Çetinkaya Aydın / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 98

1. Introduction

Today in Turkey domestic violence against women has reached such a serious level that even those who

generally ignore the women’s human rights cannot disregard it. Almost daily cases of femicide are the most

concrete evidence of the current situation of domestic violence against women in Turkey. In parallel to the

increasing number of cases of domestic violence against women, efforts to combat and to eliminate it have

also increased, especially in recent years. New policies are established, new laws are implemented, lots of

conferences, workshops, congresses etc. are held, lots of researches are conducted, lots of books and articles

are written and published, at universities new programs on gender and women’s studies are opened and so

on. However remarkable results indicating that domestic violence against women is getting decrease have

not been reached yet. On the contrary unofficial statistics reveal that there is an increase in the number of

femicide cases, ultimate form of violence against women. For example according to We Will Stop Femicide

Platform’s statistics, last year, in 2014, 294 women were killed by their intimates. And in the first 8 month

of 2015, 182 women were killed (http://kadincinayetlerinidurduracagiz.net/veriler/2349/agustos-2015-

kadin-cinayeti-gercekleri). It is also known that most of the women were killed when they attempted to

make their own decisions about their own lives.

So, the present situation can be explained like this: On the one hand there is an increasing struggle to

combat and to eliminate domestic violence against women and on the other hand there is an increasing

number of cases of domestic violence against women. Then, it seems, there is a paradox here. How this

paradox can be explained in a rational manner? What are the gaps between the studies on domestic violence

against women and reality? How these gaps can be filled to find permanent and sustainable solutions for

elimination of domestic violence against women?

At this point, in order to find reasonable answers to these questions it might be useful to review the

results of the previous researches on violence against women from a different point of view. In this context,

some common results obtained from different researches on violence against women are summarized

below:

Men hold the power within the family as a reflection of patriarchal power relations in society. So,

force/violence used by men against family members is legitimate in the event that it is considered necessary

to do so (Rittersberger-Tılıç, 1998).

Honor of family legitimizes the violence against women. Accordingly, a woman’s “dishonorable

behaviors” are not accepted and are shamed and blamed even by other women. Therefore, violence against

women for their “dishonorable behaviors” is regarded as legitimate (Rittersberger-Tılıç, 1998; Başbakanlık

Aile Araştırma Kurumu [AAK], 1995).

Women victims of domestic violence generally try to keep their family together rather than move

away. In some events, women victims of violence believe that they are responsible for the violence they

suffer. Moreover they accept and internalized violence and learn to live with it (İçli, 1994; AAK 1995;

Rittersberger-Tılıç, 1998, Gülçür, 1999).

In accordance with traditional gender roles, family members and relatives of women victims of

violence persuade them to keep their family together (AAK 1995; Yıldırım, 1998; Gülçür, 1999;

Başbakanlık Kadının Statüsü Genel Müdürlüğü [KSGM], 2009).

In accordance with a traditional common belief, violence within the family should be kept secret

from outsiders (İçli, 1994; AAK, 1995; Rittersberger-Tılıç, 1998; Gülçür 1999).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-112-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Çetinkaya Aydın / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 101

wife rather than an independent individual. So the right place of a married woman is her husband’s home.

And she must stay there even she is subjected to violence by her husband. Gönül, 28 years old, with one

child, tells how her relatives try to keep her family together:

“… Let’s save this family, there is a child, there is a home, let’s save it and, let’s give his wife back to him…” Ela,

23 years old, with two children, explains how her mother and aunt do not pay to attention the violence she suffered by

her husband and persuade her to keep her family together:

“… Firstly I told my aunt, and she said, it is not so important, we also are beaten, what is the problem. Do whatever

he wants. I said, no, I am not his slave. And my aunt said, you will be [his slave], he is your husband, if he beats you

even he kills you. Then I told my mother, and my mother said, it is not important, your father also beats me…” Meltem,

31 years old, with two children, has similar experience with her sisters and brothers:

“… My brothers and my sisters too, said, you went there [husband’s home] with your wedding dress and you will

return with your shroud, this suits us...”

The above explanations indicate that, convincing or forcing women victims of domestic violence by

their family members and/or relatives not to leave their husbands and keep their family together lead to

reproduction violence against women. However, the explanations also indicate that convincing or forcing

battered women not to leave their husbands and keep their family together strengthens the traditional family

values in the form of solidarity patterns which on the one hand enable the protection of the family but on

the other hand reproduce violence against women. Accordingly, repetitive expressions like “be patient”,

“endure the violence”,” tolerate him for the sake of your children”, “let’s save the family”, “you went

there with your wedding dress and you will return with your shroud”, “we are also beaten, what is the

problem” are solidarity patterns which enable the protection of family through the violation of women’s

human rights.

4.2. Solidarity patterns produced by the police responsible for prevention of violence against women

The interviewees were also asked the attitudes of the police when they call for help. According to the

answers 28 women out of 30 (%93) called the police for help at least once. The 20 women who called the

police said some of the police officers have an attitude that domestic violence against women is a part of

family relationships. Ece, 19 years old, with one child, explains her experience with the police:

“… I went to the police station. Most of the police officers there knew my husband. They asked me how I could

endure him. But there was an old one. He said, you are a married woman, you should endure him. Today’s women

leave their husbands for even just a slap…” Deniz, 34 years old, with two children explains the attitudes of the police

toward her:

“… One day the police came to our house for routine control. They asked me if I had any problem with my husband.

I said no. In that time my husband got better a little bit. One of the police officers said, what will you do if he does not

get better? Do you have any financial power? No. So you should endure him…” Burçin, 23 years old, with one child,

tells how the police officers tried to convince her to forgive her husband:

“… I didn’t go to the police station near our house. Because all the police officers there knew my husband and I

was afraid that they called him. I went to another police station. The police officers in that police station said me to

forgive my husband. They said, forgive your husband, you have a child… These kinds of events could occur in every

marriage… The police officers tried to convince me to forgive my husband a lot of times and I was tired to say them

no… I was so surprised and I thought whether if I relied on them or not… ” Çiğdem, 22 years old, has also similar

experience with the police:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-115-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Çetinkaya Aydın / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 102

“… I went to police. They said, you are a family, you are young, and you can solve your problems yourselves,

return to your home… This is a small town and it would be better not to be heard your problems from the others…”

According to the law in force # 6284, Protection of Family and Prevention of Violence against Women,

the police as law enforcers, are authorized and are responsible for the prevention of violence against women.

However this research results indicate that in most cases the attitudes of the police toward the women

victims of domestic violence do not comply with the provisions of the law # 6284. Unfortunately the data

obtained from the field research cannot directly explain why the police don’t take the necessary measures

stated in the law in force to prevent the domestic violence against women. Nevertheless, within the

framework of the explanations of the women victims of violence, it can be said that the police generally

enforce the law in order to protect the family, as stated in the first part of the name of the Law # 6284 rather

than to take measures, which are clearly mentioned in the provisions of the law, to eliminate domestic

violence against women.

Thus, in case the Law in question is enforced by the police to encourage the women victims of domestic

violence to return to their homes where they suffer violence and to keep their family together, traditional

family values which lead to violence against women are reproduced by solidarity patterns. Accordingly,

repetitive expressions such as “today’s women leave their husbands for even just a slap”, “you should

endure him”, “forgive your husband, you have a child”, “these kinds of events could occur in every

marriage”, “return to your home”, “it would be better not to be heard your problems from the others” can

be accepted as solidarity patterns which enable the protection of family through the violation of women’s

human rights.

4.3. Solidarity patterns produced by the women victims of domestic violence

The interviewees were asked if they think that they somehow deserve the violence to which they have

been subjected. The answers are classified and evaluated in two groups:

1) According to the answers 18 women out of 31 (%58) at least sometimes think that they deserve the

violence. Bade, 37 years old, with one child, explains how she tried to find fault with herself as an excuse

for husband’s violence:

“… At first I always asked myself if I was guilty. Did he use violence against me because of my fault? I asked

myself if I deserved it…” Rana, 34 years old, with four children, tells how she forced herself to find an excuse for her

husband’s violence:

“… At first I thought that I was guilty, because I loved him. I thought maybe he was angry about something. His

financial situation was not good, so maybe he was worried about it. Maybe I was guilty, maybe I made him angry …”

Gamze, 31 years old, with two children, explains how she legitimizes her husband’s violence in an event that she thinks

she is guilty:

“… I keep my silence if I know that I am guilty. I say, OK! I am guilty in this event. I say, I deserve it [violence].

And I keep my silence…” Banu, 28 years old, with two children, tells how she justifies her husband’s violence in

certain cases:

“… He didn’t like my parents. He didn’t allow me to call my mother. Therefore I usually called my mother without

notice to him. One day when I was talking with my mother, he saw me and he beat me. I thought I deserved it. Because

although he didn’t want me to call my mother, I called her without notice to him …”

Just like other research results on violence against women, the results of this study also show that in

certain cases violence against women is somehow justified even by the women victims of domestic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-116-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Çetinkaya Aydın / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 103

violence. And this justification provides a basis for production and reproduction of violence against women.

It is also well known that there are some social, cultural and economic reasons such as traditional family

values, concern for children, financial dependence, behind the justification of violence by the battered

women. However, whatever the reasons behind the justification of domestic violence against women the

repetitive expressions such as “I thought I deserved it [violence], “I keep my silence” “maybe I was guilty”,

“maybe I made him angry” enable at the same time the protection of family by fostering traditional family

values in the form of solidarity patterns which ultimately lead to violence against women.

2) According to the answers, 13 women out of 31 (% 42) never think that they deserve the violence.

However there are some contradictions in their explanations. For example the explanations of 10 women

who said they never find themselves guilty for the violence they suffer give also an impression that in some

cases women may deserve the violence. For example Ezgi, 44 years old, with four children, explains why

she did not find herself guilty for the violence she was subjected:

“… I never justified his violence. We [Ezgi and her co-wife] were perfect. At home we made everything perfectly.

But we were nothing to him…” Gonca, 28 years old, with three children, also tells why she didn’t think that she

deserved the violence:

“… I never found myself guilty. I never thought like that. Because I did everything properly…”

Accordingly, although the women, who never find themselves guilty for the violence they suffer, carry

out all their responsibilities in accordance with the requirements of the traditional gender roles, they suffer

from violence. And they find it unacceptable rather than the violence against women in general. Hence, it

is thought that the explanations of the women who say they never think that they deserve the violence are

not completely different from the explanations of those who sometimes think that they deserve it. Thus, it

can be argued that the expressions such as “I never justified violence, because at home we made everything

perfectly”, “I never find myself guilty, because I did everything properly” enable the protection of the

family as an institution by fostering the traditional family values which lead to domestic violence against

women.

In fact the answers given to another question related to the justification of domestic violence against

women verify the above evaluation on the attitudes of the interviewees toward the domestic violence against

women. The interviewees were also asked their opinions about the women who behave “dishonorably”

toward their husbands and their families. 8 women out of 24 (%32) stated, for example, if a woman cheats

on her husband, this is an unacceptable, “dishonorable” behavior and she deserves the violence in anyway.

That is, she should be beaten at least. Gönül, 28 years old, with one child, explains in which cases domestic

violence against women is justified:

“… I am angry with that woman. If her husband doesn’t beat her, she doesn’t have any right to behave like this. I

think she should be beaten, she should be beaten. There are a lot of women who cannot find a warm home…” Duygu,

26 years old, with two children, also agrees with Gönül:

“… She deserves the violence. Why she cheats on her husband? If I were her husband I would have been beaten

her. If I were her husband I would have kicked seven bells out of her. If I were her husband I would have kicked her to

the curb. Why she cheats on her husband? She deserves the violence. She should be punished any way…” Pınar, 24

years old, with three children, explains why a woman who cheats on her husband deserves the violence:

“… She deserves the violence. I explain the reason. If she cheats on her husband although he is nice to her, although

he doesn’t beat her, although he is a perfect husband, she deserves the violence. As a woman I can say that she deserves

the violence. This is my opinion. I know that beating is not good. But in that case she deserves the violence. I think like

this, it is not necessary to lie…”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-117-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Çetinkaya Aydın / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 106

References

Başbakanlık Aile Araştırma Kurumu. (1995). Aile İçi Şiddetin Sebep ve Sonuçları [Elektronik Sürüm].

Ankara: Bizim Büro Basım Evi.

Başbakanlık Kadının Statüsü Genel Müdürlüğü. (2009). Türkiye’de Kadına Yönelik Aile İçi Şiddet

[Elektronik Sürüm]. Ankara: Elma Teknik Basım Matbaacılık.

Crow, G. (2002). Social Solidarities. Theories, Identities and Social Change. Buckingham: Open

University Press.

Giddens, A. (1994). Beyond Left And Right. California: Stanford University Press.

Gülçür, L. (1999). A study on domestic violence and sexual abuse in Ankara, Turkey. Women for

Women’s Human Rights Reports No.4.

İçli, T. (1994). Aile İçi Şiddet: Ankara-İstanbul ve İzmir Örneği [Elektronik Sürüm]. Hacettepe

Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 11 (1-2), 7-20.

İstanbul Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi Ceza Hukuku ve Kriminolojik Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi.

(2003). Suçla Mücadele Bağlamında Türkiye’de Aile İçi Şiddet. Ülke Çağında Kriminolojik ve

Viktimolojik Alan Araştırması ve Değerlendirme. İstanbul: Beta Basım.

Kadın Cinayetlerini Durduracağız Platformu. (t.y.). Erişim: 27 Eylül 2015, Kadın Cinayetlerini

Durduracağız Platformu Ağ Sitesi, (http://kadincinayetlerinidurduracagiz.net/veriler/2349/agustos-2015-

kadin-cinayeti-gercekleri)

Neuman, W. L. (2006). Social Research Methods. Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. (6th

ed.).Boston. Pearson Education.

Rittersberger-Tılıç, H. (1998). Aile İçi Şiddet: Bir Sosyolojik Yaklaşım. O. Çiftçi (Ed.). 20. Yüzyılın

Sonunda Kadınlar ve Gelecek Konferansı (s. 119-129). Ankara: Orta Doğu Amme İdaresi Yayınları.

Sallan Gül, S. (2011). Türkiye’de Kadın Sığınmaevleri. Erkek Şiddetinden Uzak Yaşama Açılan Kapılar

mı? İstanbul: Bağlam Yayıncılık.

Theodorson, G. A. ve Theodorson A. G. (1979). A Modern Dictionary of Sociology. New York,

Hagerstown,

San Francisco, London: Barnes & Noble Books.

Yıldırım, A. (1998). Sıradan Şiddet. İstanbul: Boyut Yayın Grubu](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-120-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Savaş / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 108

1. Introduction

Through our daily lives, we are constantly bombarded with images from the media. The newspapers,

the television, the internet. There is no running away from it and actually, this is what those who prepare

the advertisements pride themselves on – they can put those images anywhere, even onto our coffee cups

or right into that video we watch online. It is also not possible to miss the pattern in which women are

usually shown in these images: mostly the focus is on their bodies, with the message being their

appearance is the most important aspect of them, and other times they are mostly shown as one-dimensional

characters even on movies. They are generally regarded as something less than they are and with this

recurring attitude the media has long helped the objectification and commodification of women.

Gallagher suggests that it wasn’tuntil the 1990s, when media coverage could no longer be dismissed in

most of the world, that the issues concerning women in media stopped being regarded as of secondary

importance to “cardinal problems such as poverty, health and education” (2002:2). On the other hand, van

Zoonen states that “[the] media have always been at the centre of feminist critique” and points out that as

early as 1963, Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique, was criticizing the media for its contribution to

the “myth that women could find true fulfilment in being only a housewife and a mother” (1994:11).

According to van Zoonen since “women’smovement is not only engaged in a material struggle about equal

rights and opportunities for women, but also in a symbolic conflict about definitions of femininity”, the

way women were represented in the media have always been an important battleground for the feminists.

She states that by the early 1970s a considerable collection of feminist action and thought about the

media was accumulated. One can only assume that works concerning the issues of women have become

more frequent after that since McClelland (1993:220) marks the start point of the concern for the patterns

for sexist visual imagery as the 1970s, following the rapid social change of the 1960s.

Concerns over the representation of women in the media have been on the quantitative –Gallagher uses

data on the underrepresentation of women- and also regarded the content analysis –the stereotypes and

socialization, pornography and ideology as van Zoonen groups the feminist themes in communication

studies. More and more frequently, though, the focus has been on the gender portrayal in the media and

how this may affect the way women perceive themselves as well as showing how the society sees them.

As van Zoonen notes, Tuchman, –whose work in the late 1970s is among the first to produce research

on this topic with a well-developed theoretical framework- comments on the fact that the media has failed

to represent the increasing numbers of women in the labour force and “also it symbolically denigrates

[women] by portraying them as incompetent, inferior and always subservient to men” (1994:16).

Kilbourne states in the third instalment of her Killing Us Softly video series (2000) that as the foundation

of the mass media, advertisements aim to sell products and they do; however, they also sell values, images

and “concepts of love and sexuality, of romance, of success... and perhaps most important of normalcy. To

a great extent advertising tells us who we are and who we should be.” As Kilbourne focuses, media does

so especially in regards to its visualization of women.

In this paper, it is my purpose to show the ways in which the mass media objectifies women, the

consequences of this behaviour on women and also the consequences on the way society regards women

and to see when this started. It is argued that the “liberalized women” actually served to the further the

material oppression of women within the capitalist system.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-122-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Savaş / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 110

for the purposes of sex and reproduction”- explaining that “[the women’s] status and subjectivity are

defined through their relationship with men”, in support of her point. Bağatur stands on the belief that

women were the primary group to be thought of as consumers –whereas men were the producers- and she

states that through “spectacularization” women were also commodified: “[W]hile women were invited to

consume more, specific guidance of this consumption towards articles related to women’s appearance made

women themselves commodities.” (2007:87).

In 1993 Steeves lists the “representations of women in global, mainstream media” as one of the Five

Global Gender Issues and also shares the belief that mass media is not a mere representative of the society

but it reinforces, not just creates, patriarchal ideologies around the world. It should, however, be noted that

Steeves’ list is questionable in the sense that it seemingly focus more on the problems of women who live

in the “developed” countries of the world. Mohanty describes this as “the typically authorizing signature

of such Western feminist writings on women in the third world” (1988:352) and is very vary of this

authorization as she draws a parallel with the “humanism as a Western ideological and political project.”

McClelland states that women and minorities are being portrayed in stereotypical roles and in

distorted or sexist images within the mass media and also believes that the visual images are powerful

means of communication which convey “intended or unintended messages” and can carry “cultural

symbolism” (1993:221). He lists the consequences of the women’s portrayal in mass media as;

objectification, seduction, self-gratification, stereotyping and underrepresentation.

Overall, it is safe to say that most scholars who write about the issues of women’s relationship to media

believe that, despite being an appropriate means to examine the production-consumption relations and

perceptions of self-image in the society, the mass media more than just reflects the social structure; it also

affects it and alters it. The two most concerning topics discussed by the literature are the lack of

representation of women in the media and how they are represented when they are.

3. A Brief Historical Review on Women’s Dual Role within the Consumer Society

“The adage ‘Consumption, thy name is women’ resonates with such venerable authority that one might

expect to find it cited in Barlett’s Familiar Quotations, attributed to some Victoria savant or to an eminent

critic of modern frippery,” are the opening words of The Sex of Things (1996). The emphasis of the book

is on the fact that despite its naturalization as an inevitable part of the women’spsychology, the “excessive

desire to consume as a peculiarly feminine quality” (Jones, 1996:27) is a historical phenomenon which

has its roots in the long transition from the aristocratic to bourgeois society (1996:1).

Of interest to note is that with the technological advances and the “industrial revolution”, it was seen as

the “men” were conquering nature. The nature had been thought of as “female” for centuries and in

accordance with this, as Jones states, women were associated with the characteristics of inconsistency,

treachery and change. The advent of liberal politics and public space, which distinguished needs as

“irrational, superfluous, or so impassioned that they overloaded the political system” and “those that were

rationally articulated and cast in terms appropriate to being represented and acted through normal

political process” (1996:15), was one of the structural changes that reinforced the propensity to feminize

the realm of consumption. In line with the view of women being inconsistent, the first set of needs defined

were identified with women.

The division of labour of the capitalist system which constructed the household with the male

breadwinner, defining his labour as the wage labour, further reinforced the differences between the

household and the market place, the female provisioners and male workers, the consumers and the producers

(1996:15). With Say’s famous theory of supply creating its own demand taken basis, the production](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-124-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Savaş / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 112

could “well be described as an emblematic figure for that Paris being constructed through capitalism as the

capital of desire” (1992:142).

The image of women as housewives, which ruled as the dominating image of women in the media

until the late twentieth century, reinforcing the household structure has been present since at least the

nineteenth century, too. Loeb paints a picture of how women were represented as housewives of the

Victorian England advertisements. According to Burdon’s review on her book, Loeb argues “as

consumers of the merchandise and the media that represented it, women played a major role in the

nineteenth-century commercial revolution documented by [the descriptive catalog of Victorian and

Edwardian advertisements]” (1997:348). Burton notes that the advertisements were widely based on the

gendered stereotype of the idea that the home was the woman’s domain and hence the “Victorian notions

of the ‘respectable feminine’” were pivotal to the process of the products of the commercial capitalism

being naturalized and the icons of mass production being domesticated. Burton points out that Loeb has not

concerned herself with explaining whether women were affected by these advertisements but counts that

images of consumer-as-mother was also played upon by the advertisers and tells us that it was realized that

“sexy women would sell” (Loeb, 1994:57 cited in Burton, 1997:349).

Even though the spread of images through technological advancement has definitely accelerated these

processes and the needs of the market along with women’s position in the society altered the domineering

portrayal, one thing we can draw from this review is that neither women’s role as consumers nor the

female body’s commodification were natural. They were historical processes which came to be within

capitalist society.

4. Women’s Representation in Media

The headline of the Turkish newspaper Referans for 17-18th

of April 2010 read: “Not much changed in

the advertisement strategies during the past fifty years! Sexist advertisements are dead, sexy woman is on

the shop window”. Özçelik states in the article that even though the sexist advertisements of the 1950s

which showed women as the housewives who are only born to please their husbands no longer exist, the

one thing that remains is the commodification of women. While women reshaped their existence within

the social, political, artistic and work lives, the advertisers realized that telling women to buy one product,

or else their husband would leave them, did not work anymore. As a result, advertisements moved towards

“disguised sexist” ones or ones within which women were outright used as sexual objects. The new way

to sell was to tell women that with the right cosmetic products they could look like Hollywood stars and

with the help of photoshop, unattainable goals were worked into women’s subconscious.

According to Bağatur’s analysis on the Turkish print media’s representation of women from 1930 to

1970, women in this period were not as sexualized as they are today. Rather the focus was on their role

as the housewife or their facial beauty and how they needed to keep it to hold onto their husband or to

find one. Advertisers were in a dilemma, Bağatur explains, on regards the representation of women in

advertising since the newly forming republic expected her to take upon her shoulders by simultaneously

being modern and traditional: “While they were invited to beautify themselves in accordance with the

Western norms with new cosmetics and fashion products, they were also continuously associated with

traditional roles of housewife and mother.” (Bağatur, 2007:110).

She presents advertisements of product such as butter, pasta and cleaning items showing how they

played on the stereotype of women being responsible for cooking and cleaning for the family. Where

woman is the natural bearer of the tasks such as cooking and serving for the family, it is usually the

daughter who helps her, while the man is either the husband who comes home happy to see a meal served](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-126-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Savaş / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 115

media’s portrayal and they do feel pressured to measure up to this ideal image, how else could have

the diet, the cosmetics, the cosmetic surgery could make millions of dollars each year?

To conclude, it should be noted that women’s oppression continues with force within our society. The

fact that this has reached such early ages is quite threatening. Even if their representation in the media is

not the primary concern of women in the entire world, considering its effects and the fact that it reinforces

the way that women are thought of, it is high time that precautions be taken on the issue.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Assoc. Prof. Sheila Margaret Pelizzon for her guidance and continued support.

As always, to my family.

References

Bağatur, Sine (2007). “Engendering Consumption: Commodification of Women through Print Media

with Specific Reference to the Turkish Case”. Unpublished Master Thesis, Middle East Technical

University

Becker, Anne E. and Hamburg, Paul (1996). “Culture, the Media, and Eating Disorders”, Harvard

Review of Psychiatry, 4:3, pp 163-167

Becker, Howard S (2002). “Studying the New Media”, Qualitative Sociology, Vol. 25, No. 3; 337-343

Brooks, D. E. and Hébert, L. P. (2006). “Gender, Race and Media Representation”, in The SAGE

Handbook of Gender and Communication, B. Dow and J. Woods (eds.), Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications, Inc, pp 297-319

Burton, Antoinette (1997). “Reviewed work(s): Consuming Angels: Advertising and Victorian Woman by

Lori Anne Loeb”, The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 69, No. 2, pp 348-350

Ceulemans, Mieke and Fauconnier, Guido (1979). Mass Media: The Image Role and Social

Conditions of Women. Paris: UNESCO; [New York: distributed by Unipub]

De Grazia Victoria and Ellen Furlough (eds.). The Sex of Things: Gender and Consumption in Historical

Perspective, Berkeley, L.A. and London: University of California Press, 1996

Gallagher, Margaret (2002). “Women, Media and Democratic Society: In Pursuit of Rights and

Freedoms”, EGM

Ingham, Helen (1995). “The Portrayal of Women on Television”. Retrieved from:

http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Students/hzi9401.html

Irigaray, Luce (1985). “Women on the Market” in This Sex Which is Not Mine, Ithaca: Cornell

University Press, pp 170-191](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-129-320.jpg)

![Ayşe Savaş / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 116

Jhally, Sut (1989). “Advertising, Gender and Sex: What‟s Wrong with a Little Objectification?” in

Working Papers and Proceedings of the Center for Psychosocial Studies (edited by Richard Parmentier

and Greg Urban) No. 29. Retrieved from: http://www.sutjhally.com/articles/whatswrongwithalit/

Kilbourne, Jean (2000). Killing Us Softly 3: Advertising’s Image of Women.

MacDonald, Myra (1995). Representing Women: Myths of Femininity in the Popular Media. London:

HodderArnold

McClelland, John (1993). “Visual Images and Re-Imaging: A Review of Research in Mass

Communication” in Women in Mass Communication, ed. Pamela J. Creedon, Newbury Park, CA: Sage

Mohanty, Chandra Talpade (1988). “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial

Discourses”, Feminist Review, No. 30, 61-88

Ono, Kent A. and Buescher, Derek T. (2001). “Deciphering Pocahontas: Unpacking the

Commodification of a Native American Woman”, Critical Studies in Media Communication, 18, 23-43

Özçelik, Sıla. "Seksist Reklamlar Öldü, Seksi Kadın Vitrinde” Refereans [İstanbul] 17-18 April

2010: 11

Peach, Lucinda Joy (ed.) (1998). Women in Culture: A Women’s Studies Anthology, Massachusetts and

Oxford: Blackwell Publishers

Roberts, Mary Louise (1998). “Gender, Consumption, and Commodity Culture”, The American

Historical Review, Vol. 103, No. 3, 817-844

Senghas, Sarah (2006). “Slender, Sexy Women Portrayed in Movies, TV, Magazines and

Advertisements” Retrieved from:

http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/32112/sexist_stereotypes_in_the_media.html?cat=9

Steeves, Leslie (1993). “Gender and Mass Communication in a Global Context” in Women in Mass

Communication, Creedon, Pamela J (ed.), Sage Publications, Second Edition, pp 32-60

Van Zoonen, Liesbet (1994). Feminist Media Studies. London; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/59efbcce-7adc-4ccf-9a99-524cc539d6df-160605031959/85/My-published-research-130-320.jpg)

![Ayşegül Gökalp Kutlu / METU GWS Conference 2015

Page | 129

especially in the Eastern and South Eastern parts of Turkey and among families within the lower socio-

economic classes. It was not until the 1980s that Turkish women would indulge in a new wave of feminism

and address their own problems such as domestic violence, harassment, honour killings, virginity

examinations, family-oriented gender rules and the patriarchal hegemony.

One of the key achievements of the feminist movement in Turkey was the Domestic Violence Act

(1998). The Act introduced legal sanctions for not only abusive and violent husbands but for the male

members of the family. It also made it possible for the prosecutors to issue protection orders, providing

shelters for the victims, perpetrators to be kept away from the family home for a specific time period,

confiscation of his arms, and payment of alimony, and in case of noncompliance with the court order,

imprisonment for up to six months (Aslan-Akman&Tütüncü, 2013: 93).

In addition to the strengthening feminist movement, the EU candidacy also contributed to policy reform

in gender equality. The EU’s conditionality, together with Turkey’s feminist movement, resulted in

important amendments in the Constitution, and adoption of the new Civil, Penal Codes and the Labour Act,

establishment of the Women-Men Equal Opportunities Commission, approval of the Istanbul Convention

and adoption of the new Law on the Protection of the Family, and approval of the optional protocol of the

CEDAW which led the way for direct application to the CEDAW Committee for women who are exposed

to discrimination.

With the constitutional amendments in 2001 and 2004, some gender equality provisions were introduced.

In 2001, the clause “The family is the foundation of the Turkish society and based on the equality between

the spouses” was added. In 2004, the statement “[...] Men and women have equal rights. The State shall

have the obligation to ensure that this equality exists in practice”, was introduced and in 2010, “Measures

taken for this purpose should not be regarded against the principle of equality” was added after this

sentence. The famous clause on superiority of international law was also included in 2004 amendments,

stating that the provisions of international agreements that Turkey is a signatory (such as CEDAW or the

Istanbul Convention) will bear the force of law, and in case of a conflict between domestic law and a

provision of an international treaty that Turkey is a signatory, Turkey has to follow the provisions of the

international agreement.

The new Civil Code was adopted in 2001. It established the legal marriage age as seventeen for both

men and women and contended that no one can be forced to marry. It also abolished the concept of men