Mental Health Tribunal Powers: Final Report on Part V of Mental Health Act 1983

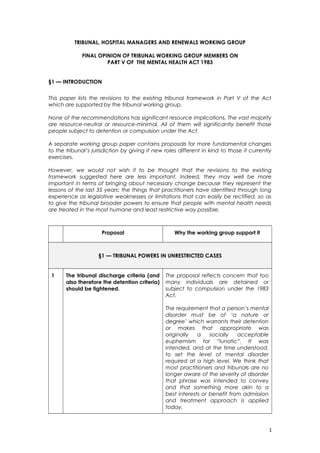

- 1. TRIBUNAL, HOSPITAL MANAGERS AND RENEWALS WORKING GROUP FINAL OPINION OF TRIBUNAL WORKING GROUP MEMBERS ON PART V OF THE MENTAL HEALTH ACT 1983 §1 — INTRODUCTION This paper lists the revisions to the existing tribunal framework in Part V of the Act which are supported by the tribunal working group. None of the recommendations has significant resource implications. The vast majority are resource-neutral or resource-minimal. All of them will significantly benefit those people subject to detention or compulsion under the Act. A separate working group paper contains proposals for more fundamental changes to the tribunal’s jurisdiction by giving it new roles different in kind to those it currently exercises. However, we would not wish it to be thought that the revisions to the existing framework suggested here are less important. Indeed, they may well be more important in terms of bringing about necessary change because they represent the lessons of the last 35 years: the things that practitioners have identified through long experience as legislative weaknesses or limitations that can easily be rectified, so as to give the tribunal broader powers to ensure that people with mental health needs are treated in the most humane and least restrictive way possible. Proposal Why the working group support it §1 — TRIBUNAL POWERS IN UNRESTRICTED CASES 1 The tribunal discharge criteria (and also therefore the detention criteria) should be tightened. The proposal reflects concern that too many individuals are detained or subject to compulsion under the 1983 Act. The requirement that a person’s mental disorder must be of ‘a nature or degree’ which warrants their detention or makes that appropriate was originally a socially acceptable euphemism for “lunatic”. It was intended, and at the time understood, to set the level of mental disorder required at a high level. We think that most practitioners and tribunals are no longer aware of the severity of disorder that phrase was intended to convey and that something more akin to a best interests or benefit from admission and treatment approach is applied today. 1

- 2. 2 The Act should commence with a set of statutory guiding principles, such as the principles currently set out in the Code of Practice. This will give statutory effect to guiding principles of the kind set out in the Code of Practice and require a tribunal to apply them when making decisions about whether to detain or discharge a citizen, e.g. 2. Guiding principles (1) All persons dealt with under this Act shall be cared for and treated— (a) in accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights; (a) wherever possible, without recourse to formal powers or compulsion; (b) in the least controlled facilities possible; (c) in such a way as to promote to the greatest practicable degree their self-termination and personal responsibility; (2) Before a court, tribunal or individual makes any decision under this Act concerning a patient’s care or treatment, or the use of compulsion, the body or person in question shall have regard to— (a) the requirements of subsection (1) above; (b) the ascertainable wishes and feelings of the patient; (c) the likely effect on him of any change in his circumstances; (d) the suitability of the proposed care and treatment in the context of his age, gender, sexual orientation, social, cultural and religious background, and other personal characteristics; (e) any harm which he or other persons have suffered or are at risk of suffering; (f) the likelihood of the care or treatment alleviating or preventing a deterioration of the patient’s condition; (g) his needs; (h) how capable those caring for him are of meeting his needs. 2

- 3. 3 A tribunal should be required to specify the risks of continuing detention or compulsion, Some practitioners limit their risk assessments to the harm that is likely if the patient is released. When considering its discretionary power of discharge, a tribunal should be required to record both its assessment of the risks associated with discharge (e.g. physical harm to self or others) and the risks associated with continued detention (e.g. loss of family contact, income, employment prospects, liberty, etc). Essentially a balance-sheet approach. 4 The tribunal’s discretionary power of discharge should be restored to what was intended, and always was the case, prior to the decision in GA v Betsi Cadwaladr University LHB [2013] 0280 (AAC). The GA decision was completely at odds with the history of the legislation, the intention of Parliament and the statutory scheme and may have had a significant effect on the tribunal discharge rate. The legislation needs to be urgently amended so as to restore the historic position since 1959 that a tribunal may at its discretion discharge a patient, subject only to the usual judicial review principles, i.e. a decision to discharge at the tribunal’s discretion can only be challenged if irrational, etc. 5 Provided a bed will be available within the next 28 days, In unrestricted cases a tribunal which does not discharge a patient should be able to direct transfer to another hospital with a view to facilitating their discharge from hospital at a later date. At present the tribunal may only recommend transfer to another hospital. In appropriate cases this will enable a tribunal to direct a patient’s transfer to a hospital nearer to their home, to a less secure facility, etc. If a tribunal is sufficiently expert to overrule the responsible clinician by rescinding the section and directing discharge then a fortiori it is also competent to overrule the responsible clinician or hospital managers by directing a relaxation of the conditions of detention or compulsion, e.g. by directing the patient’s transfer or the grant of leave of absence. 6 In unrestricted cases a tribunal which does not discharge a patient should be able to direct that the patient be granted leave of absence. At present the tribunal may only recommend the grant of leave of absence. A tribunal which is competent to terminate detention is competent to authorise a relaxation of the conditions of detention. 3

- 4. Following such a direction, the responsible clinician (RC) would have the same power to revoke the leave of absence and to recall the patient to hospital, and the same power to vary the conditions of leave, as s/he has in the case of a patient to whom the RC has granted leave, provided that s/he acts in good faith and there has been a relevant change of circumstances since the tribunal made its decision. 7 In unrestricted cases a tribunal should be able to direct that the patient be received into guardianship. At present the tribunal may only recommend reception into guardianship. Guardianship has always been woefully under-used as an alternative to detention or a CTO. Such a power may unleash the potential of guardianship as a light- touch social services-led alternative to detention or CTOs. The tribunal may require the local social services authority to provide a care plan, and must take into account its representations as to the suitability of guardianship, but ultimately tribunal- imposed guardianship as a means of terminating detention would not require local authority consent. 8 A tribunal should not have a power to direct or recommend that a patient is made the subject of a CTO on such conditions as it thinks fit. A CTO regime is very different to guardianship. A guardian’s powers are limited by statute to specifying a place of residence, requiring the patient to attend specified activities and requiring access to the patient. Guardianship is therefore a light-touch order. The statute already provides for detained patients to be transferred into guardianship and extending this power to tribunal does not change the existing framework. CTOs are more extensive, the conditions are not limited by statute and potentially very invasive, the underlying section 3 application remains in force, and there is a power of recall. 4

- 5. If tribunals are given a power to impose CTOs, some patients will think twice before applying for a review out of fear that they may end up on a Draconian CTO that will be in force for far longer than the section 3 application to which they are subject. Tribunals will come to be seen by some as part of the state apparatus that imposes compulsion rather than as a court that exists solely to review and terminate infringements of liberty that are not justified. The evidence may suggest that tribunals are quite risk-averse when it comes to CTO regimes (the tribunal discharge rate in CTO cases is 3.4%, i.e. 96-97% of applications to discharge a CTO are refused). The effect of giving a tribunal a CTO power (or a power of conditional discharge) may be that in future some tribunals will discharge subject to a CTO and recall civil patients who presently they discharge from section absolutely. One could end up with an even larger number of citizens subject to old section 3s and civil powers of recall lasting many years. 9 If CTOs are to continue, tribunals will need much greater powers to terminate CTOs (including an unfettered discretionary power of discharge) and power to vary the conditions of CTOs it does not discharge. The tribunal discharge rate in CTO cases is 3.4%, i.e. 96-97% of applications to discharge a CTO are refused. If CTOs are to remain then, given the terms of reference, there will need to be much tighter control over their use and duration. §2 — TRIBUNAL POWERS IN RESTRICTED CASES Section 37/41 cases 10 Provided a place is available within 28 days, a tribunal should have power to direct that a restricted patient be transferred to another hospital. The reasons why a tribunal’s powers are extremely limited are historical. When the government lost the X case, it was forced by the European Court of Human Rights to empower tribunals to release patients who it considered no longer required detention in hospital. 5

- 6. However, it went no further than it was required to do. It did not authorise a tribunal to discharge restricted patients who would still benefit from being in hospital but no longer needed to be detained in hospital; it did not authorise a tribunal to recommend leave of absence or transfer to a less secure hospital; and it did not authorise a tribunal to lift the section 41 restrictions if satisfied they were no longer required whilst continuing detention in hospital under section 37. It is illogical that a tribunal which is authorised by statute to discharge a restricted patient absolutely cannot take many steps along the road to discharge that fall short of this. There is no good reason why a court/tribunal’s powers should be less than those exercisable by the Secretary of State or civil servants. 11 Where no bed at another hospital is available within 28 days, a tribunal should have power to recommend that a patient is transferred to a less secure hospital of the kind specified by it. The tribunal should have a power to reconvene if the recommendation is not carried out. Where a recommendation is not carried out, the effect would be to set the clock running for European Convention purposes. In other words, there would be the possibility of judicial review proceedings or an ECHR challenge if the patient was then detained in more secure conditions than necessary for a very prolonged further period. 12 A tribunal should have power to direct that a restricted patient be granted leave of absence on such conditions as it specifies. Following such a direction, the responsible clinician and Secretary of State would have the same power to revoke the leave and to recall the patient to hospital, and the same power to vary the conditions of leave, as they have now provided they act in good faith and there has been a relevant change of circumstances since the tribunal made its decision. 6

- 7. 13 A tribunal should have the power to terminate the section 41 restrictions if satisfied that they are no longer necessary in order to protect the public from serious harm. The Secretary of State has this power and the tribunal should have the same powers as the Secretary of State and civil servants. This falls squarely within the tribunal’s area of expertise. Section 47/49 and 48/49 hearings 14 The functions currently exercised by the Parole Board in respect of section 47/49 patients should be exercised by the tribunal which considers the patient’s case under section 74. It appears that the risk assessment process undertaken by the Parole Board substantially duplicates that undertaken already by the tribunal. This is a considerable waste of money and resources. Even when one allows for the fact that some financial and other resources will need to be transferred from the Parole Board to the tribunal to compensate for that part of the work which is not a duplication, there is an opportunity for considerable financial savings. 15 Where practicable the medical member of the tribunal in such cases should have significant forensic experience This recommendation addresses a concern that the medical member in such cases should have significant forensic experience. 16 Consideration should be given to co-opting members of the Parole onto the tribunal This would require an amendment to the primary legislation. 17 Section 74 should be redrafted in plain English Many practitioners and patients find section 74 confusing. Conditional discharge 18 A conditionally discharged patient shall be absolutely discharged by the tribunal unless the tribunal is satisfied that the special restrictions are necessary in order to prevent a risk of serious harm to the public. Section 75 allows a tribunal to do one of three things: nothing, vary the conditions of discharge, direct that the restrictions shall cease to have effect. This is too general. The special restrictions exist to protect the public from serious harm and that should be the test for absolute discharge in section 75. §3 — OTHER TRIBUNAL ISSUES 7

- 8. 19 Invalid applications: Where a tribunal finds that a Part II application is invalid, it shall record its finding and direct the patient’s release from detention or compulsion pursuant to that application. This shall not prevent the patient’s detention under a new, valid, application. For many years it has been believed that a tribunal has no authority to discharge a section 2, 3 or 7 application which is invalid/materially defective. In other words it is neither bound to discharge the application and nor does it have a discretionary power to discharge it. The supposed authority for this interpretation is dicta of Ackner LJ in R v Hallstrom and another, ex p W [1986] 1 QB 824. In fact, Neill and Glidewell LJJ expressly refused to follow Ackner LJ on this point and Ackner LJ did not consider the earlier case of Re VE (mental health patient) [1973] 1 QB 452 where the Court of Appeal indicated that a patient held under an invalid application should have been discharged by the tribunal. This recommendation provides a much more cost-effective way of revoking invalid applications than the present mechanism. The tribunal may defer its decision in appropriate cases to enable a new application to be made that complies with the legal formalities. 20 A tribunal should have no such power in Part III cases. Part III orders are made by a court and the authority to detain a person subject to a Part III direction is not one which derives solely from the 1983 Act (the individual will be subject to a sentence of imprisonment, remand in custody, etc). 21 Tribunal membership: The statute should include a requirement that judges/legal members of the tribunal (including the members of an Upper Tribunal panel hearing a mental health case) are able to demonstrate suitable expertise and experience as a solicitor or barrister in practice of the application of the Mental Health Act 1983 For economic reasons the current trend is towards generic tribunal judges. While that approach is convenient from an administrative point of view it must come at a cost in terms of the effectiveness and confidence of the judge and their understanding of practice issues. 8

- 9. Indeed, the whole original purpose of tribunals was that a conventional court was not appropriate to the particular field because of its specialist nature. There is therefore an argument that tribunal judges should demonstrate experience and expertise in the field, similar to the section 12(2) requirement for medical practitioners. This recommendation was opposed by the tribunal but had the unanimous support of all other working group members. 22 Tribunal rules: Section 78 of the Act, which deals with tribunal rules, should require the Secretary of State and the tribunal to seek to ensure that the tribunal rules are as simple and short as possible, in plain English, understandable by most applicants, and wherever possible encourage informality and flexibility. There has been a very unhelpful tendency in recent years for mental health rules and procedures to become ever more complicated. The tribunal rules are significantly longer than their predecessor rules. The rules should be drafted so as to encourage informality; keeps costs down by minimising form-filling, directions and interlocutory applications; and enable the rules to be flexibly interpreted and applied to suit the mental health and needs of the patient. All of this is in keeping with the original idea of tribunals. A Anselm Eldergill, 11 September 2018 9

- 10. Indeed, the whole original purpose of tribunals was that a conventional court was not appropriate to the particular field because of its specialist nature. There is therefore an argument that tribunal judges should demonstrate experience and expertise in the field, similar to the section 12(2) requirement for medical practitioners. This recommendation was opposed by the tribunal but had the unanimous support of all other working group members. 22 Tribunal rules: Section 78 of the Act, which deals with tribunal rules, should require the Secretary of State and the tribunal to seek to ensure that the tribunal rules are as simple and short as possible, in plain English, understandable by most applicants, and wherever possible encourage informality and flexibility. There has been a very unhelpful tendency in recent years for mental health rules and procedures to become ever more complicated. The tribunal rules are significantly longer than their predecessor rules. The rules should be drafted so as to encourage informality; keeps costs down by minimising form-filling, directions and interlocutory applications; and enable the rules to be flexibly interpreted and applied to suit the mental health and needs of the patient. All of this is in keeping with the original idea of tribunals. A Anselm Eldergill, 11 September 2018 9