The NHS in the past, Eldergill

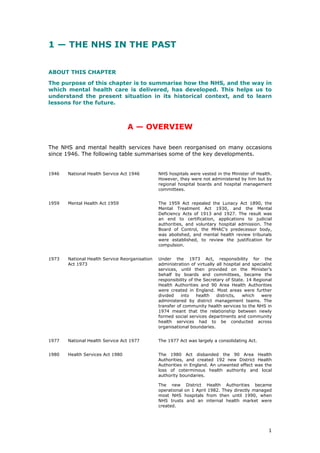

- 1. 1 1 — THE NHS IN THE PAST ABOUT THIS CHAPTER The purpose of this chapter is to summarise how the NHS, and the way in which mental health care is delivered, has developed. This helps us to understand the present situation in its historical context, and to learn lessons for the future. A — OVERVIEW The NHS and mental health services have been reorganised on many occasions since 1946. The following table summarises some of the key developments. 1946 National Health Service Act 1946 NHS hospitals were vested in the Minister of Health. However, they were not administered by him but by regional hospital boards and hospital management committees. 1959 Mental Health Act 1959 The 1959 Act repealed the Lunacy Act 1890, the Mental Treatment Act 1930, and the Mental Deficiency Acts of 1913 and 1927. The result was an end to certification, applications to judicial authorities, and voluntary hospital admission. The Board of Control, the MHAC’s predecessor body, was abolished, and mental health review tribunals were established, to review the justification for compulsion. 1973 National Health Service Reorganisation Act 1973 Under the 1973 Act, responsibility for the administration of virtually all hospital and specialist services, until then provided on the Minister’s behalf by boards and committees, became the responsibility of the Secretary of State. 14 Regional Health Authorities and 90 Area Health Authorities were created in England. Most areas were further divided into health districts, which were administered by district management teams. The transfer of community health services to the NHS in 1974 meant that the relationship between newly formed social services departments and community health services had to be conducted across organisational boundaries. 1977 National Health Service Act 1977 The 1977 Act was largely a consolidating Act. 1980 Health Services Act 1980 The 1980 Act disbanded the 90 Area Health Authorities, and created 192 new District Health Authorities in England. An unwanted effect was the loss of coterminous health authority and local authority boundaries. The new District Health Authorities became operational on 1 April 1982. They directly managed most NHS hospitals from then until 1990, when NHS trusts and an internal health market were created.

- 2. 2 1982 Mental Health (Amendment) Act 1982 The 1982 Act preserved the structure of the 1959 Act but gave persons subject to, or at risk of, compulsion various additional rights. The remit and powers of mental health review tribunals were extended, a new Mental Health Act Commission was established, and most in-patients detained for 28 days or more benefited from new statutory consent to treatment procedures. 1983 Mental Health Act 1983 The 1983 Act was a consolidating Act. In due course, it was amended by the Mental Health (Patients in the Community) Act 1995 and the Crime (Sentences) Act 1997. 1990 National Health Service & Community Care Act 1990 The underlying philosophy of the 1990 Act was to separate out the functions of purchasing and providing health and social care, so as to create an ‘internal market’ in the health service and a ‘mixed economy of care’ in relation to social services: (1) The Act introduced an internal NHS market, by separating the planning and purchase of hospital and community health services from their provision. It did this by providing for the establishment of semi-autonomous bodies called NHS trusts. Trusts had to compete with each other for orders placed by District Health Authorities. (2) The Act created fund-holding practices of GPs, which were given a sum of money to purchase, from providers of their choosing, some of the hospital and community health services that would otherwise have been purchased by the District Health Authority. (3) The Act provided that any community care services that could be provided by a local authority could also be provided by the independent sector. Just as the role of Health Authorities became one of purchasing health services provided by NHS trusts, so local authorities were developed as ‘enabling’ and ‘commissioning’ agencies, seeking out and purchasing community care services from a range of public and non-public providers. Care programme approach (HC(90)23) In 1990, the care programme approach was launched. It applied to all patients who need psychiatric treatment or care. It required health and social services authorities to develop care programmes based on systematic arrangements for treating patients in the community. The underlying purpose was to ensure the support of mentally ill people in the community, thereby minimising the risk of them losing contact with services, and maximising the effect of any therapeutic intervention. 1991 Patient’s Charter In October 1991, the Patient’s Charter was published as part of a national policy initiative to define standards for public services. It set out a list of guarantees for patients, although these were not legally enforceable. 1994 Supervision registers In 1994, the Government extended the care programme approach by requiring NHS trusts to keep supervision registers.

- 3. 3 Their purpose was to enable NHS trusts, and other service providers, to identify all individuals known ‘to be at significant risk of committing serious violence or suicide or of serious self-neglect, as a result of severe and enduring mental illness.’ Guidance on discharge (HSG (94)27) 1994 also saw the publication of further guidance concerning discharge. This aimed to ensure that psychiatric patients were discharged only when and if they were ready to leave hospital; that any risk to the public or to the patients was minimal; and that they received the support and supervision they needed from the responsible agencies. The guidance also required an independent inquiry after any homicide committed by a patient who had been in touch with psychiatric services. 1995 Health Authorities Act 1995 The 1995 Act attempted to streamline central management and to encourage the integrated purchasing of primary and secondary care. The Act abolished the Regional Health Authorities, which were replaced by eight regional NHS Executive offices. In addition, it provided for the merger of District Health and Family Health Service Authorities, to form new unitary Health Authorities (in effect, joint purchasing bodies). The new authorities were expected to work with local authority social services departments in the commissioning of social care, so as to ensure a more integrated strategy for local services. Mental Health (Patients in the Community) Act 1995 The 1995 Act revised the legal arrangements for patients in the community. A new power was introduced which enabled an unrestricted patient detained for treatment to be made subject to ‘after- care under supervision’ when s/he left hospital. The Act also amended the law concerning patients who were lawfully or unlawfully absent from hospital or the place where they were required to reside. Thus, the Act provided for each of the three situations in which an unrestricted patient who has been detained for treatment may be in the community: s/he may have leave to be absent from hospital, be absent without leave, or have been discharged and no longer liable to detention. Introduction of a departmental after- care form In February 1995, the Department of Health circulated an after-care form, which it recommended hospitals use for all patients being discharged from psychiatric in-patient treatment. This form was devised in response to a recommendation in the Report of the Inquiry into the Care and Treatment of Christopher Clunis. Building Bridges Building Bridges was also published in 1995. It was a further element of the Government’s ten-point plan in response to public concern about the discharge of patients from hospital. It stressed that the care programme approach was the cornerstone of the Government’s mental health policy. It also emphasised the need to adopt a tiered approach. The purpose of this was to focus the most resource- intensive assessment, care and treatment on the most severely mentally ill people, whilst ensuring that all patients receiving specialist psychiatric services received the basic elements of CPA.

- 4. 4 Patients with less complex needs would still receive systematic assessment, be assigned a key worker, and receive monitoring and review of a simple care plan (‘minimal CPA’). Each patient’s details were to be entered on a CPA information system, and an initial needs assessment was to be carried out by a mental health professional (‘pre-CPA assessment’). 1997 National Health Service (Primary Care) Act 1997 Before 1997, all GPs worked under a standard national contract; and most of the payments to them were made through a complex system of fees and allowances aligned to nationally agreed services. The 1997 Act allowed Health Authorities to pilot different arrangements for delivering primary medical services. Pilot schemes were local agreements negotiated with the Health Authority. They enabled professionals to negotiate their own service agreement, including an annual price for the service. This reduced unnecessary bureaucracy and most of the need to count individual services to individual patients. 1998 April. Creation of Health Action Zones. Health Action Zones were introduced in April 1998. Since then, 26 zones have been set up in England, covering a combined population of 13 million people. The zones were intended to improve the health of local people in areas of high deprivation, and over £100m of funding was made available for them in their first two years. December. Publication of Modernising Mental Health Services. In December 1998, the Government promised to modernise mental health services by providing safe, sound and supportive services; and it set out its strategy for achieving these objectives. 1999 March. Clinical Governance (HSC 1999/065) The first departmental clinical governance guidance was published in March 1999. April. Establishment of Primary Care Groups. Fund-holding was abolished on 1 April 1999, when 481 Primary Care Groups were created in England, as Health Authority committees. These new groups involved all GPs in an area, together with community nurses. They were to be responsible for improving the health of their communities, commissioning services, developing primary and community care, and exercising functions delegated to them by Health Authorities. The plan was that, over-time, they might become Primary Care Trusts under the Health Act 1999, taking over the commissioning of most hospital services. April. Establishment of NICE The National Institute for Clinical Excellence was established as a Special Health Authority on 1 April 1999. It was to be responsible for producing advice for clinicians and managers on the clinical and cost effectiveness of drugs, diagnostic tests and surgical procedures. It also sets clinical guidelines and a clinical audit framework. April. Publication of 3rd edition of the Code of Practice. On 1 April 1999, a third edition of the Code of Practice on the Mental Health Act 1983 came into force. According to it, good practice requires more emphasis on risk management and less on individual liberty.

- 5. 5 June. Health Act 1999. The Health Act 1999 Act provided for the abolition of GP fund-holding; the creation of Primary Care Trusts; improved partnership arrangements; the preparation of Health Improvement Plans; new arrangements for special hospitals; increased powers for the Secretary of State; the establishment of a Commission for Health Improvement; and Health Authority funding based on performance. July. Local Government Act 1999. The Local Government Act imposed a statutory duty on local authorities to deliver ‘best value’ in the performance of their functions. ‘Best value’ means securing continuous improvement in the exercise of the authority’s functions, having regard to economy, efficiency and effectiveness. Under the Act, the Secretary of State may prescribe performance indicators, and set national standards that authorities must meet in order to discharge the duty; the Audit Commission may carry out inspections to assess compliance; and the Secretary of State has a wide range of intervention powers. November. National Service Framework for Mental Health. The National Service Framework set seven key standards for mental health services, in five areas: mental health promotion; primary care and access to services; effective services for people with severe mental illness; caring about carers; and preventing suicide. Standards four and five aim to ensure that each person with a severe mental illness receives the range of mental health services they need; that crises are anticipated or prevented where possible; that prompt and effective help is available if a crisis occurs; and that there is timely access to an appropriate and safe mental health place or hospital bed as close to home as possible. 2000 July. Publication of the NHS Plan The NHS Plan is the Government’s blueprint for the NHS. Important elements of the plan include national service frameworks; care trusts; a new concordat with the private and voluntary sector and the NHS; and the establishment of new public or departmental bodies, including: a Modernisation Board (to oversee implementation of the NHS plan); a Modernisation Agency (to help redesign local services); a Commission for Health Improvement (to inspect NHS organisations every four years); a National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE); a National Clinical Assessment Authority (to assess doctors’ performance); a UK Council of Health Regulators; an NHS Appointments Commission; Patient Advocacy and Liaison Services (PALS);

- 6. 6 a National Independent Reconfiguration Panel (to advise on contested major service configuration changes); independent local advisory forums; and scrutiny of health services by local authority scrutiny all-party committees. July. Care Standards Act 2000 The Care Standards Act 2000 reformed the regulatory system for care services in England and Wales. The Act established a new regulatory body for social and private health care services, known as the National Care Standards Commission. It also created a new council responsible for registering social care workers, setting standards in social care work and regulating the education and training of social workers in England. It authorised the Secretary of State to maintain a list of individuals who are considered unsuitable to work with vulnerable adults. July. Local Government Act 2000. The Local Government Act provided for the establishment of local authority executives. Under these arrangements, a local authority’s social services functions are discharged by the executive, rather than by a social services committee. Authorities operating executive arrangements must set up overview and scrutiny committees, which will hold the executive to account. An overview and scrutiny committee may review and scrutinise executive decisions, and recommend that they are reconsidered or arrange for the authority to review them. December. White Paper on the Mental Health Act 1983. The new civil framework set out in the White Paper All retains of the existing short-term powers. In addition, the police may enter private premises without a warrant, if advised by ‘a mental health practitioner with appropriate seniority and experience that the person appears to be in immediate need of care and control.’ Compulsion for more than 28 days will require a care and treatment order made by a tribunal. Initially, these orders will last for up to six months, and they may authorise treatment in hospital (as with section 3) or outside hospital (as with section 17 leave, guardianship, and after-care under supervision). All patients must first be placed under the new 28-day order before an application may be made to a tribunal for a six month order. 2001 May. Health & Social Care Act 2001 The Health & Social Care Act 2001 contains further provisions concerning partnership arrangements; provides for the establishment of Care Trusts; public-private partnerships; new provisions concerning patient information; extension of prescribing rights; new provisions concerning long- term care; various changes to Part II services. November. National Health Service Reform and Health Care Professions Bill. The National Health Service Reform and Health Care Professions Bill was introduced in the House of Commons on 8 November 2001. The Bill takes forward the proposals set out in ‘Shifting the Balance of Power’ that require primary legislation.

- 7. 7 The Bill provides for the creation of Strategic Health Authorities; for most of the functions of Health Authorities to be conferred on Primary Care Trusts; for strengthening the Commission for Health Improvement; for the abolition of Community Health Councils; for the establishment of independent Patients’ Forums and a Commission for Patient and Public Involvement in Health; and for the creation of a Council for the Regulation of Health Care Professionals. It establishes a duty of partnership on NHS bodies and the prison service. 2002 National Health Service Reform and Health Care Professions Act 2002 As to the terms of the Bill, see above. Mental Health Act 2002 A new Mental Health Act may also be enacted. New NHS structures Existing Health Authorities and community NHS trusts will be disestablished, and new merged Health Authorities established, on 1 April 2002. A second wave of PCTs will become operational. For the vast majority of staff in NHS regional offices, Health Authorities, Community NHS Trusts and Primary Care Groups, the changes mean a move to new organisations. 2003 1 April 2003 The offices of the new regional directors of health and social care will be established. The Department of Health’s eight NHS regional offices will close. B — THE LEGISLATION & GUIDANCE NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE ACT 1946 At the time of its foundation, the National Health Service inherited over one hundred mental health asylums, each with an average population of over 1,000 patients. The number of in-patients was to peak in 1954. The original management structure of the NHS, which persisted from 1948 until 1974, had 14 Regional Hospital Boards and 35 Teaching Hospital Boards reporting direct to the Ministry of Health. Between them, these Hospital Boards supervised about 400 Hospital Management Committees, which managed the hospitals. Although NHS hospitals were vested in the Minister of Health, they were not administered by him but by these regional hospital boards and hospital management committees. The function of the boards was to administer on behalf of the Minister, and subject to regulations, the hospital and specialist services provided in their areas. Within the limits of a fixed budget set by national government, local diversity was considerable, and national policy-making frequently proceeded by exhortation. There was no national cadre of National Health Service administrators, and administrative staff were recruited by the local boards and committees. Medical staff made up a significant proportion of the membership of these administrative bodies. While central government controlled the budget, doctors controlled what happened within that budget.

- 8. 8 Primary care services were run by 117 Executive Councils. Community health services were the responsibility of county councils and boroughs, which the Act defined as ‘the local health authority’. Local health authorities had a duty to provide a mental health service designed to meet the needs, at all ages, of those suffering from mental disorder. They were required to submit to the Minister of Health proposals for carrying out their functions. Each of them established a Health Committee, which in turn could refer powers relating to mental health services to a Mental Health Sub-Committee. The 1946 National Health Service Act stripped the Board of Control of nearly all its functions, but it continued as an inspectorate of mental hospitals (particularly with regard to detention). The Board had been established under the Mental Deficiency Act 1913, as the successor body to the Lunacy Commission (which had to be renamed and re- established when it acquiring functions with regard to mental deficiency). The Ministry of Health Act 1919 transferred responsibility for the Board from the Home Office to the new Ministry of Health. The Lunacy Commission had originally been established in 1845 ‘as a Victorian Ministry of Mental Health without a Minister of Mental Health.’ MENTAL HEALTH ACT 1959 In 1954, a Royal Commission was appointed to review the law concerning mental illness and deficiency. It reported in 1957,2 and many of the recommendations in the ‘Percy Report’ were adopted in the Mental Health Act 1959. Paragraph 317 of the report spelt out the Commission’s view as to when the use of compulsory powers was justified, and this paragraph is reproduced below. Minister of Health Regional Hospital BoardExecutive Council Local Health Authority National Health Service Act 1946 Dental, etc, services Medical practitioner services Health Committee Hospital Management Committees

- 9. 9 WHEN COMPULSION IS JUSTIFIED Percy Report, para. 317 ‘We consider that the use of special compulsory powers on grounds of the patient's mental disorder is justifiable when: (a) there is reasonable certainty that the patient is suffering from a pathological mental disorder and requires hospital or community care; and (b) suitable care cannot be provided without the use of compulsory powers; and (c) if the patient himself is unwilling to receive the form of care which is considered necessary, there is at least a strong likelihood that his unwillingness is due to a lack of appreciation of his own condition deriving from the mental disorder itself; and (d) there is also either— (i) a good prospect of benefit to the patient from the treatment proposed — an expectation that it will either cure or alleviate his mental disorder or strengthen his ability to regulate his social behaviour in spite of the underlying disorder, or bring him substantial benefit in the form of protection from neglect or exploitation by others; or (ii) a strong need to protect others from anti-social behaviour by the patient.’ The Government’s objectives The terms of the Mental Health Act 1959 gave expression to the Commission’s views about when compulsion is necessary or justified. During a Parliamentary debate on 5 May 1959, the Minister of Health explained the Government’s aims in relation to the new civil procedures in the following terms: ‘We had in mind all the time to try and assemble a structure which would reflect the balance of the considerations we must have in mind. They are, firstly, the liberty of the subject, secondly, the necessity of bringing treatment to bear where treatment is required and can be beneficial to the individual and, thirdly, the consideration of the protection of the public. All through I have tried steadily to keep in mind that what we are trying to do is to erect as balanced a structure as we may, which can give effect to all those things in harmony with each other.’3 Repeal of certification procedures Under the Lunacy Act 1890 and related legislation, the order of a justice of the peace, or some other judicial authority, had generally been necessary before a person could be detained in hospital or received into guardianship. The Royal Commission of 1954–57 advocated the repeal of these certification procedures. In their place, it recommended that detention or guardianship should be authorised if an application was accepted by the relevant hospital or local social services authority. The Royal Commission’s opinion was that, ‘... a sufficient consensus of medical and non-medical opinion on the need to compel a patient to accept hospital or community care would normally be provided through [1] an application for the patient’s admission made by a relative or mental welfare officer, ... [2] two supporting medical recommendations, [3] the acceptance of the patient as suitable for the form of care recommended, and [4] the continuing power of discharge vested in the nearest relative, the hospital or local authority medical staff, the members of the hospital management committee or local authority, and the Minister of Health. To

- 10. 10 refer the application and medical recommendations to a justice of the peace before the patient’s admission would not in our view provide a significant additional safeguard for the patient …’4 Creation of mental health review tribunals The most distinctive feature of the post–1959 application procedures is therefore that an individual is deprived of his liberty following an application made, not to a court, but to the managers of a hospital. Similarly, guardianship and after-care under supervision result from an application’s acceptance by a local social services authority or Health Authority. The procedures cannot properly be described as administrative because, in constitutional terms, they involve the detention or restraint of one of the Queen’s subjects. But, equally, it would be inaccurate to describe them as a judicial process, for no judicial authority, such as a tribunal, is involved. Because the proposed new procedures did not involve a judicial body, the Royal Commission recommended that if, after the event, a patient wanted the justification for compulsion to be formally reviewed this need should be met by the establishment of new independent review bodies.5 Their establishment would give those patients who desired it opportunities to have the justification for the use of compulsion investigated by a strong independent body consisting of both medical and non-medical members.6 Abolition of the Board of Control The Board of Control was abolished by the 1959 Act. Before then, applications were forwarded to it for scrutiny, and it had a discretion to direct a patient’s discharge if unamended statutory documents were materially defective.7 The Percy Commission recommended that this function should be performed by hospital staff at the time of admission. It stated that where the admission papers did not appear to be valid, the hospital should not accept them. If necessary, the patient should be cared for informally, or by use of emergency procedures, while the documents were corrected or new documents prepared.8 The function of scrutinising documents was not restored in 1983 to the body that is the modern day successor of the Board, namely the Mental Health Act Commission. THE WATER TOWER WATERSHED In March 1961, Enoch Powell (the then Minister of Health) delivered his famous Water Tower Speech. He announced that ‘in fifteen years time, there will be needed not more than half as many places in hospitals for mental illness as there are today. Expressed in numerical terms, this would represent a redundancy of now fewer than 75,000 hospital beds.’ The two main features of government policy became that hospital treatment should be provided in psychiatric units in District General Hospitals, and that as much care and treatment as possible should be provided outside hospital. In the late 1960s, Hospital Boards were asked to provide a comprehensive service for all patients at District General Hospitals. Progress was fairly slow. In 1966, there were still 107 mental illness, and 66 mental handicap hospitals and units, with 200 or more beds. The Seebohm Report of 1968 noted that the ‘widespread belief that we have community care of the mentally disordered is, for many parts of the country, still a sad illusion, and judging by published plans, will remain so for years ahead.’

- 11. 11 INSTITUTIONAL ABUSE The late 1960s and the 1970s were punctuated by a series of reports into the ill- treatment and abuse of patients in mental health hospitals. Some of the most infamous were the Report of Government Inquiry into the Sans Everything Allegations (1968); the Ely Hospital Inquiry Report (1969); the Whittingham Hospital Report (1972); the St Augustine’s Committee of Enquiry Report (1976); and the Boynton Report concerning Rampton Hospital (1980). NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE REORGANISATION ACT 1973 By the end of the 1960s a consensus was developing that the tripartite structure of the NHS, established in 1948, was a source of problems. A series of reviews proposed a more integrated system of management. The Royal Commission on Local Government in England (the Redcliffe-Maud Report) articulated the main perceived benefits of reunifying hospital and community services within local government. In contrast, the Porrit Report recommended the unification of hospital, community health and GP services within the NHS. These discussions culminated in the passage of the National Health Service Reorganisation Act 1973, which introduced changes with effect from 1 April 1974. On that date, responsibility for the administration of virtually all hospital and specialist services, until then provided on behalf of the Secretary of State (Minister of Health) by boards and committees, became the responsibility of the Secretary of State. The reorganisation aimed to unify health services by bringing under one authority all the services that had previously been administered by regional hospital boards, hospital management committees, executive councils and local health authorities. 14 regional health authorities (RHAs) were created in England, the members of which were appointed by the Secretary of State. They were responsible for planning local health services. Under the region-wide authorities, 90 area health authorities were established in England, with a Chair appointed by the Secretary of State, and non-executive members appointed by the RHA and local authorities. Most areas were further divided into health districts administered by district management teams. The transfer of community health services to the NHS in 1974 meant that the relationship between newly formed social services departments and community health services had to be conducted across organisational boundaries. In order to foster their co-ordination, the boundaries of the area health authorities were designed to match those of the local authorities providing social services. The relationship between the appointed members of the NHS and the elected members of local government took place within Joint Consultative Committees; and officers from health and social services met in Joint Care Planning Teams. A substantial amount of formal planning machinery was therefore established. General practice General practitioners remained as independent contractors under the 1973 Act. However, the role of the executive councils was taken over by family practitioner committees (FPCs), which were responsible for GPs, dentists, pharmacists and opticians.

- 12. 12 Other changes The 1973 Act created community health councils (‘CHCs’) at district level, to represent the views of the public. In 1974, the interim report of the Butler Committee was published in April 1974, and this led to the creation of a network of regional secure units (medium secure units). NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE ACT 1977 The 1977 Act was largely a consolidating Act. As enacted, it therefore provided for three types of Health Authority: Area Health Authorities, Family Health Services Authorities and Regional Health Authorities. HEALTH SERVICES ACT 1980 The reorganised structure introduced in 1974 was criticised for containing too many tiers of administrative decision-making, leading to bureaucracy and delays. The Royal Commission on the National Health Service, which reported in 1979, recommended that there should be only one level of administrative authority below the level of the regional health authority. In December 1979, the DHSS and Welsh Office published a consultative paper entitled ‘Patients First’, which proposed removing the area tier and establishing district health authorities to combine the functions of areas and districts. These recommendations led to the Health Services Act 1980, which disbanded the 90 Area Health Authorities, and created 192 new district health authorities in

- 13. 13 England. An unwanted effect of this was the loss of coterminous health authority and local authority boundaries. The new District Health Authorities became operational on 1 April 1982. They directly managed most NHS hospitals from then until 1990, when NHS trusts and an internal health market were created. New special health authorities were also created. Their main responsibility at this time was to run postgraduate teaching hospitals in London. MENTAL HEALTH (AMENDMENT) ACT 1982 The 1982 Act preserved the structure of the Mental Health Act 1959, but gave those subject to, or at risk of, compulsion various additional rights. In particular, the remit and powers of mental health review tribunals were extended; a new Mental Health Act Commission was established; and patients on the longer-term orders were given the right to a second-opinion in relation to certain treatments. Under the 1983 Act, a person may not be detained for more than 72 hours unless the managers of a hospital have accepted an application for his admission (under Part II of the Act), or his detention there has been authorised by a criminal court or by the Home Secretary (under Part III of the Act). THE NHS IN THE 1980s The 1980s were characterised by an intensification of central scrutiny and control:

- 14. 14 • In 1982, a system of annual performance reviews was launched. Ministers held meetings with regional chairs, to set and then monitor progress towards targets. The regional chairs held similar meetings with the districts within their constituencies, setting up a chain of review. • During 1981/82, area health authorities were required to make efficiency savings in order to generate funds for new developments. In 1984, these programmes were renamed ‘Cost Improvement Programmes’. • From 1982, NHS managers carried out a series of cost-effectiveness reviews of areas such as transport services and residential accommodation. • In August 1982, a review of NHS audit arrangements was announced. • In September 1983, the first set of performance indicators was published. These included information about clinical services, finance, staffing levels and estate management. District Health Authorities were required to invite tenders from in-house staff and outside contractors, in order to test the cost-effectiveness of their own catering, domestic and laundry services. • In 1983, the Griffiths Report was published. It recommended that all levels within the NHS should operate under the control of a single general manager or chief executive. The report also recommended the establishment of a Health Services Supervisory Board, to determine policy and objectives, and an NHS Management Board, to perform an executive role. Regional and district chairs were to ensure that accountability and review extended through to unit level. • In June 1984, the circular ‘Implementation of the NHS Management Inquiry’ authorised the adoption of these recommendations, and required District Health Authorities and units to appoint a general manager. • In January 1988, following concern about health service funding and its inadequacies, the Prime Minister announced a fundamental review of the NHS. This was conducted by a Cabinet Committee. • In January 1989, the White Paper, ‘Working for Patients,’ proposed an NHS internal market that separated ‘purchasers’ from ‘providers’. Health authorities would purchase services from independent NHS trusts, after assessing local needs and developing a strategic plan for those needs. They would also monitor the delivery of the services commissioned by them. GPs also would be offered the option of becoming ‘fundholders’, able to purchase most services on behalf of their patients. • In May 1989, the NHS Policy Board and NHS Management Executive (NHSME) were created. The intention was to split NHS policy and management. This distinction was symbolised by the move of the NHSME from London to Leeds. • In 1989, the Government issued a health circular called, ‘Discharge of Patients from Hospital’ (HC(89)5). This stated that no patient was to be discharged until the doctors concerned had agreed, and management was satisfied, that everything reasonably practicable had been done to organise the care the patient would need in the community.

- 15. 15 NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE & COMMUNITY CARE ACT 1990 The 1990 Act introduced an internal market, by separating out the planning and purchase of hospital and community health services on the one hand, and their provision on the other. It did this by providing for the establishment of semi- autonomous bodies known as NHS trusts, to assume responsibility for the ownership and management of hospitals and facilities previously managed or provided by the local District Health Authority.9 NHS trusts had no money paid to them directly by the Secretary of State, but instead had to compete with each other for orders placed by District Health Authorities. These District Health Authorities could choose to purchase health care from private sector institutions. Prior to placing contracts, the DHA was expected to assess what the local health needs were, and to develop (with the assistance of its public health team) a strategy for meeting them. The arrangements which District Health Authorities made with the trusts for the provision of hospital and community health services did not constitute an ordinary contract enforceable at law, but were subject to arbitration by the Secretary of State. ‘Extra-contractual’ referrals catered for patients who required some treatment, operation or package of care which fell outside the contract. Such additional costs were met by District Health Authorities on an individual basis. Health authorities Under the 1990 Act, three different kinds of health authority were responsible for NHS functions at a regional or local level, and the basic structure was as follows: At the top of the pyramid was the Secretary of State for Health, the government minister in charge of the Department of Health, responsible for the NHS in England, and answerable to Parliament. The Department of Health, and in particular the NHS Management Executive, was responsible for the strategic planning of the health service. The NHS Management Executive set up seven regional outposts to assist it in establishing the NHS trusts and monitoring their performance. Under the Department of Health were 14 Regional Health Authorities, which were given boards of executive and non-executive directors. They planned health care in each region, managed the implementation of the 1990 Act reforms, allocated resources to primary and secondary care, and provided a range of region-wide services. The Secretary of State issued directions to them about the performance of their functions. Secondary care was commissioned by District Health Authorities, which were allocated resources by their local Regional Health Authority. The district authorities assessed the local population’s need for health care and purchased hospital and community health services for them. Some of them merged to form larger purchasing units, or collaborated in ‘purchasing consortia’. Family Health Services Authorities regulated and managed the services provided by general practitioners, dentists, pharmacists and opticians. They paid general practitioners in accordance with previously agreed contracts, and investigated complaints relating to such services. Although District and Family Health Service Authorities established joint management arrangements in many areas, the law required them to maintain separate existences.

- 16. 16 Fund-holding The 1990 Act also provided for the creation of fund-holding practices of GPs. Fund-holding practices were given a sum of money (known as ‘an allotted sum’) with which to purchase, from whatever provider they saw fit, some of the hospital and community health services which would otherwise have been purchased by the local District Health Authority. There were therefore two types of purchasers of services: District Health Authorities and fund-holding practices.10 D E P A R T M E N T O F H E A L T H N H S E xecu tiv e R eg io n a l o ffices (8 ) S E C R E T A R Y O F S T A T E R eg io n a l H ea lth N H S T ru sts (4 1 9 )A u th o rities (8 ) D istrict H ea lth A u th o rities (1 1 2 ) F a m ily H ea lth S erv ices A u th o rities (9 0 ) G P F u n d h o ld ers (8 ,5 0 0 ) D irectly M a n a g ed U n its (2 2 ) G en era l P ra ctitio n ers (2 7 ,0 0 0 ) N H S S T R U C T U R E P R IO R T O 1 A P R IL 1 9 9 6

- 17. 17 Community care services The Act introduced similar reforms with regard to local authorities and the provision of community care. Here too, the underlying philosophy was to separate out the functions of purchasing and providing such care, so as to create a ‘mixed economy of care’ in relation to social services. Just as the role of Health Authorities became one of purchasing health services provided by NHS trusts, so local authorities were developed as enabling and commissioning agencies, seeking out and purchasing community care services from a range of public and non-public providers. Implementation of the 1990 Act On 1 April 1991, the 1990 Act came into effect, and the first wave of 57 NHS trusts and 306 GP fund-holders was launched. A second wave of NHS trusts and GP fund-holders began operation on 1 April 1992. In April 1993, 139 new NHS trusts came into being, making a total for England of 289. By 1 April 1994, there were a total of 419 NHS trusts and 96 per cent of hospital and community health funding was spent on services provided by trusts. By then, some 9,000 GPs had also become fund-holders, representing over half of all eligible practices, and serving approximately 36 per cent of the population. The ‘internal market’ was slow to develop. When factors such as access to services were taken into account, many local trusts were natural monopoly providers. Block contracts for services tended to be used, sometimes differing little from the global budget allocations they had replaced. Patients might then follow contracts, rather than vice versa. Thus, limited progress was made towards developing an internal market, and co-operation and partnership between purchasers and large local providers was a common approach. CARE PROGRAMME APPROACH (1990) In 1990, the care programme approach was launched (HC (90)23). It applied to all patients who needed psychiatric treatment or care. It required health and social services authorities to develop care programmes based on systematic arrangements for treating patients in the community. The underlying purpose was to ensure the support of mentally ill people in the community, thereby minimising the risk of them losing contact with services, and maximising the effect of any therapeutic intervention. All care programmes were to include systematic arrangements for assessing the health care needs of patients who could potentially be treated in the community. A key worker was to be appointed for the patient. The key worker’s role was to keep in close touch with the patient, and to monitor that the agreed health and social care was given. S/he was to maintain sufficient contact with the patient, and advise professional colleagues of any change of circumstances that might require review and modification of the care programme. Every reasonable effort was to be made to maintain contact with the patient and her/his carers, in order to find out what was happening, to sustain the therapeutic relationship, and to ensure that the patient and any carers knew how to make contact with the key worker or other professional staff. PATIENT’S CHARTER (1991) In October 1991, the Patient’s Charter was published as part of a national policy initiative to define standards of service within public services. It set out a list of ‘rights’ for patients, although these standards were not legally enforceable.

- 18. 18 CLINICAL OUTCOMES GROUP (1992) The Clinical Outcomes Group was established in 1992, to promote a multi- professional approach to clinical audit. The group placed an emphasis on linking clinical audit to other programmes, such as resource or risk management, quality assurance, research, development and education. SUPERVISION REGISTERS (HSG (94)5) In 1994, the requirement to keep supervision registers, which were an extension of the care programme approach, was introduced. The purpose of the registers was to enable NHS trusts, and other NHS provider units, to identify all individuals known ‘to be at significant risk of committing serious violence or suicide or of serious self-neglect, as a result of severe and enduring mental illness.’ The guidelines stated that consideration for registration should take place as a ‘normal part’ of discussing a patient’s care programme before he leaves hospital. The decision as to whether a patient was registered rested with the consultant, although other members of the team should be consulted. Judgements about risk should be based on detailed evidence, and the evidence should be recorded in written form and be available to relevant professionals. GUIDANCE ON DISCHARGE (HSG (94)27) New guidance on discharge sought to ensure that psychiatric patients were discharged only when and if they were ready to leave hospital; that any risk to the public or to patients themselves was minimal; and that patients received the support and supervision they needed from the responsible agencies. The guidance also required an independent inquiry after any homicide committed by a patient who had been in touch with psychiatric services. DEPARTMENTAL AFTER-CARE FORM (February 1995) In February 1995, the Department of Health circulated an after-care form designed to be used for all patients discharged from in-patient treatment. The use of the form, though not mandatory, was strongly recommended as constituting good practice. It was devised in response to a recommendation in the Report of the Inquiry into the Care and Treatment of Christopher Clunis (North West London Mental Health NHS Trust, 1994). HEALTH AUTHORITIES ACT 1995 The main purpose of the Health Authorities Act 1995, which came into force on 1 April 1996, was to streamline central management of the NHS, and to encourage the integrated purchasing of primary and secondary care. Two main changes were made: • Firstly, the abolition of the Regional Health Authorities, the number of which had already been reduced from 14 to 8 on 1 April 1994,11 and their replacement by eight NHS Executive regional offices. These offices provided a link between central management and the local NHS trusts. They were responsible for monitoring trusts; developing the purchasing function within the health service; ensuring that national policies were implemented; approving applications for GP fund-holder status; setting fund-holder budgets; and arbitrating disputes. • Secondly, the merger of District Health Authorities and Family Health Services Authorities, to form joint health purchasing bodies. The new Health Authorities were expected to work with local authorities with regard to the commissioning of social care, and their establishment meant the creation of a single authority at local level with responsibility for implementing national health policy.

- 19. 19 The functions which the new Health Authorities assumed following this merger included the following: • Evaluating the health and healthcare needs of the local population. • Establishing a local health strategy to implement national priorities and meet local health needs. • Implementing this local health strategy by purchasing health services for patients through contracts with NHS and other providers. • Monitoring the delivery of health services to ensure that the objectives were achieved. • Bringing pressure to bear on providers to raise the quality of care and efficiency by setting standards, monitoring performance, and exercising choice between competing providers. • Working with and influencing other statutory and voluntary organisations to improve people’s health. Regional offices (8) SECRETARY OF STATE NEW STRUCTURE OF THE NHS Management Contracts General PractitionersGP Fundholders Health Authorities (90-100) NHS Trusts (430) (27,000)(8,500) NHS EXECUTIVE (HQ) POST 1 APRIL 1996

- 20. 20 MENTAL HEALTH (PATIENTS IN THE COMMUNITY) ACT 1995 Section 117 of the Mental Health Act 1983 imposes a statutory duty on Health Authorities and local social services authorities to provide after-care to patients who leave hospital having been detained there for treatment. The 1995 Act introduced a new power which enabled a unrestricted patient entitled to after- care to be made subject to ‘after-care under supervision’ on leaving hospital. The Act also amended the law concerning patients who are lawfully or unlawfully absent from hospital or the place where they are required to reside. Thus, the Act provides for each of the three situations in which an unrestricted patient who has been detained for treatment may be in the community — s/he may have leave to be absent from hospital, or s/he may be absent from there without leave, or s/he may have been discharged and no longer liable to detention. BUILDING BRIDGES DOCUMENT (November 1995) Building Bridges stressed that the care programme approach is the cornerstone of the Government’s mental health policy. It also emphasised the need to adopt a tiered approach. The purpose of this is to focus the most resource-intensive assessment, care and treatment on the most severely mentally ill people, while ensuring that all patients in the care of the specialist psychiatric services receive the basic elements of CPA. Patients with less complex needs should still receive systematic assessment, be assigned a key worker, and receive monitoring and review of a simple care plan. A minimal CPA would apply to patients who have limited disability/ health care needs arising from their illness and have low support needs which are likely to remain stable. They will often need regular attention from only one practitioner, who will also fulfil the key worker role. Each patient’s details should be entered on a CPA information system, and an initial needs assessment be carried out by a mental health professional (‘pre-CPA assessment’). If a patient needs only a minimal CPA there will be no need for a multi-disciplinary meeting. It is important that the individual concerned and his or her carer(s) are involved as much as possible in the care planning process. All aspects of the care planning process should involve the user, his or her advocate, carers and/or interested relatives. A full assessment of risk, covering both risk to the patient and others, should be part and parcel of the assessment process. If the patient has been an in-patient, the keyworker should ensure before discharge that elements of the plan necessary for discharge are carried out. This will include the patient’s needs for medication, therapy, supervision and accommodation. In particular, those taking decisions on discharge have a duty to consider both the safety of the patient and the protection of other people. No individual should be discharged from hospital unless and until those taking the decision are satisfied he or she can live safely in the community, and that proper treatment, supervision, support and care are available. The keyworker is the linchpin of the CPA. S/he should be selected at the needs assessment meeting and, since s/he is vital to the success of the whole process, identified as soon as possible. This is particularly the case when patients are soon to be discharged from hospital. The decision as to who should be the key worker should take into account the patient’s needs: if housing and financial concerns and family problems are uppermost, a social worker is likely to be the most suitable candidate. The patient will need to know that the key worker (or an alternative worker) is available when things are difficult. Therefore, the key worker should ensure that patients and their carers have a contact point which is always accessible. Keeping in touch must also be assertive and key workers should not rely on the patient contacting them.

- 21. 21 GENERAL ELECTION OF 1997 A Labour Government was elected in May 1997. In December 1998, the new Government published, ‘Modernising Mental Health Services,’ in which it promised to modernise mental health services by providing safe, sound and supportive services. The objectives included good risk management; early intervention; better outreach; integrated forensic and secure provision; a modern legislative framework; effective care processes; patient and user involvement; and promoting good mental health. NATIONAL HEALTH SERVICE (PRIMARY CARE) ACT 1997 Before 1997, general practitioners delivered care to patients under a nationally determined standard contract. Most of the payments to them were made through a complex system of fees and allowances aligned to nationally agreed services, without any local flexibility. The 1997 Act allowed Health Authorities, and now Primary Care Trusts, to pilot different arrangements for delivering primary medical services. These pilot schemes allow them to work with practices to develop services for patients that fit with the key priorities in the local Health Improvement Programme. The essence of pilot scheme contracts for personal medical services is that they are a locally negotiated agreement. Providers of primary services (GPs, nurses, etc) can agree with the Health Authority or PCT a total price to be paid annually, often in 12 monthly instalments. Such agreements therefore allow professionals to negotiate the terms of their agreement for service provision; and they reduce unnecessary bureaucracy, and most of the need to count individual services to individual patients. PMS pilot schemes can take many forms. For example, they can include salaried GPs employed by PCTs or community trusts; no patient list options; specialist service options; and an extended nursing role. Legislation allows additional services to be built into a PMS agreement. These are known as ‘Plus’ services, and are typically those services that are currently provided by a range of community health care providers. PMS Plus Pilots can deliver area-wide primary care services under the auspices of a single primary care organisation; reduce bureaucracy and administrative costs between service providers; and/or offer an enhanced range of services. 85 pilot schemes were established on 1 April 1998, involving around 400 GPs and covering over 600,000 patients. A second wave of pilot schemes, involving 106 projects, became operational during October 1999, followed by a further 80 on 1 April 2000. There are now 269 pilot schemes operating around the country. The Health Authority funded the services provided under a pilot scheme from its cash-limited allocation under section 97(3).12 CREATION OF HEALTH ACTION ZONES (1998) Since April 1998, 26 health action zones have been set up in England covering a combined population of 13 million people. The zones are intended to improve the health of local people in areas of high deprivation, poor health and service pressure by creating partnerships between health authorities, local authorities, community groups, local businesses and voluntary groups. Their function is to trigger health action programmes, and to develop and implement a health strategy to deliver within their area measurable improvements in public health and in the outcomes and quality of treatment and care.

- 22. 22 Over £100m of funding was made available for the new zones in their first two years, and the zones are expected to last between five and seven years. CLINICAL GOVERNANCE GUIDANCE (March 1999) The first tranches of clinical governance guidance were published in March 1999, under Health Service Circular HSC 1999/065 in England. NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF CLINICAL EXCELLENCE (April 1999) The National Institute for Clinical Excellence was established by the Secretary of State as a Special Health Authority on 1 April 1999. It produces formal advice for clinicians and managers on the clinical and cost effectiveness of new and existing technologies, including drugs, diagnostic tests and surgical procedures. It sets clinical guidelines and a clinical audit framework. NEW CODE OF PRACTICE (April 1999) The Secretary of State published a third edition of the Code of Practice in April 1999. According to this version, good practice now requires that greater emphasis is placed on risk assessment and management, and less on the importance of individual liberty. CREATION OF PRIMARY CARE GROUPS (April 1999) On 1 April 1999, 481 Primary Care Groups were established in England as Health Authority committees.13 The groups covered populations ranging from around 50,000 to 250,000. Unlike fundholding, the new PCGs involved all GPs in an area, together with community nurses. Primary Care Groups were to be responsible for improving the health of their local community, commissioning services, developing primary and community care, and exercising functions delegated to them by Health Authorities. The plan was that they might become Primary Care Trusts under the Health Act 1999, taking over responsibility for commissioning the majority of hospital services. Until April 2000, all primary care groups were on what is known as level one or two, acting as sub-committees of their local health authority. At level one, a PCG merely supported the health authority in its traditional role of commissioning care for its population. At level two, a PCG took on responsibility for at least 40% of its unified budget, including funds for hospital and community health services, GP prescribing, and cash-limited funding for GP practice staff, premises and computers. In its second year a level two PCG had to take on at least 60% of its budget. At level three, the PCG became a freestanding primary care trust (PCT), assuming responsibility for commissioning the vast majority of hospital and community health services. At level four, the PCT could supplement its commissioning role by providing community health services for its population, employing all the relevant community health staff. HEALTH ACT 1999 (June 1999) The Health Act 1999 received Royal Assent on 30 June 1999. Part I implemented many of the proposals in the White Papers The new NHS and Putting Patients First that required primary legislation. This part therefore made a number of changes to the structure of the NHS in England and Wales.

- 23. 23 HEALTH ACT 1999 Key reforms 1. Abolition of GP fund-holding 2. Provision for the creation of Primary Care Trusts 3. Improved partnership arrangements 4. Preparation of Health Improvement Plans 5. New arrangements for special hospitals 6. Increased powers for the Secretary of State 7. Establishment of a Commission for Health Improvement 8. Health Authority funding based on performance 9. Various changes to the provision of Part II services Creation of Primary Care Trusts Section 2 of the 1999 Act provided for the establishment of new NHS bodies called Primary Care Trusts. These trusts, constituted as a new tier of administrative body below Health Authorities, were to have similar responsibilities to PCGs; and were also to involve other health professionals, social services and members of the local community. Primary Care Trusts are to take on the function of arranging the provision of health services (‘commissioning’), a function previously exercised by Health Authorities and GP fund-holders. Although the Act does not specify what services Primary Care Trusts will or will not commission, the intention was that responsibility for commissioning the majority of hospital and community health services would be delegated to them. In some cases, the new trusts may also provide hospital and community health services for their local population under Part I of the 1977 Act, a function currently performed by NHS trusts. Partnership arrangements The Health Act 1999 created a new duty of co-operation within the NHS,14 and extended the duty of co-operation between NHS bodies and local authorities in England and Wales.15 Sections 26 to 32 contain measures to strengthen partnership working, both within the NHS and between the NHS and local authorities. They create a new duty of co-operation within the NHS and extend the duty between NHS bodies and local authorities; provide a new statutory mechanism for strategic planning to improve health and health care services; provide for NHS bodies and local authorities to make payments to one another; and enable them to make use of new operational flexibilities to improve the way health and health-related functions are exercised.

- 24. 24 Abolition of Joint Consultative Committees As a result of the new partnership arrangements, the Joint Consultative Committees (JCCs) originally established by section 22(2) of the NHS Act 1977 were considered no longer necessary, and they were therefore abolished. Health Improvement Programmes Section 28 of the Health Act 1999 imposed a statutory requirement on Health Authorities to prepare plans to improve the health of the local population, and the provision of health care to it. It also imposed a duty on Primary Care Trusts, NHS trusts, and local authorities to participate in their preparation. All of these parties are required to have regard to their local plan in exercising their functions. High security psychiatric services The Secretary of State commissions high security psychiatric services for people detained under the Mental Health Act who have dangerous, violent or criminal propensities.16 Prior to the Health Act 1999, Ashworth, Broadmoor and Rampton Special Hospitals were managed outside the normal hospital system by Special Health Authorities established under section 11 of the 1977 Act. The Health Act 1999 Act provided that NHS trusts in England and Wales could, with Secretary of State’s approval, provide high security psychiatric services. The underlying aim was to address the problems of isolation of the special hospitals by allowing greater integration of secure provision.17 Should the function of commissioning high security psychiatric services be delegated to Health Authorities in the future, this will be done by regulations. Increased powers for the Secretary of State The Health Act 1999 increased the Secretary of State’s powers in relation to the NHS: The 1999 Act empowered the Secretary of State to establish NHS trusts to provide goods and services for the purposes of the health service, and enabled him to confer in an NHS trust’s establishment order a duty to provide particular goods or services at or from particular hospitals, establishments or facilities.18 The Secretary of State can therefore specify a particular type of service, such as ambulance services, which a trust must provide, and a particular site or associated sites from which the services must be provided. With regard to the exercise of the Secretary of State’s functions by Health Authorities, Special Health Authorities and Primary Care Trusts, the Secretary of State was given power to determine the level to which functions are devolved, while maintaining control over how the functions are exercised. The Secretary of State was also empowered to direct a Special Health Authority to exercise specified functions of Health Authorities or Primary Care Trusts. The 1990 Act conferred on NHS trusts a substantial degree of autonomy, and the 1999 Act gave the Secretary of State a general power to give directions in respect of an NHS trust’s full range of statutory functions. Commission for Health Improvement Having imposed a statutory duty of quality on health service bodies, the Health Act 1999 also established a commission to monitor and help improve quality.19 The Commission for Health Improvement is responsible for monitoring the quality of care for which NHS bodies are responsible through a variety of reviews and investigations. It carries out regular inspections every three to four years, and has the power to look at adverse incidents.

- 25. 25 The Commission’s establishment was accompanied by the dissolution of the Clinical Standards Advisory Group (CSAG). Funding based on performance The 1999 Act provided for the allocation of additional funding to Health Authorities on the basis of their past performance. Part II services The Health Act 1999 provided new powers for the Secretary of State to require persons providing Part II services to have indemnity cover (section 9), a new structure for the remuneration of Part II practitioners (section 10, not yet in force), and further provision for the disqualification of such practitioners by the NHS tribunal on the grounds of fraud (section 40, again not yet in force). MODERNISING THE CARE PROGRAMME APPROACH (October 1999) The booklet sets out changes to the care programme approach that take account of available evidence and experience. Some of the key requirements are the integration of the CPA and care management; the appointment of lead officers within each trust and local social services authority; the introduction of two CPA levels (standard and enhanced); the removal of the previous requirement to maintain a supervision register; and the use of the term ‘care co-ordinator’ in place of ‘keyworker’. NATIONAL SERVICE FRAMEWORK (November 1999) The National Service Framework set seven key standards in five areas, which were to be delivered from April 2000: Standard 1 • Mental health promotion Standards 2 & 3 • Primary care and access to services Standards 4 & 5 • Effective services for people with severe mental illness Standard 6 • Caring about carers Standard 7 • Preventing suicide Each standard is supported by a rationale, by a narrative that addresses service models, and by an indication of performance assessment methods. Each standard also indicates the lead organisation and key partners. Standards four and five aim to ensure that each person with severe mental illness receives the range of mental health services they need; that crises are anticipated or prevented where possible; that prompt and effective help is provided if a crisis occurs; and that there is timely access to an appropriate and safe mental health place or hospital bed as close to home as possible. Performance is to be assessed at a national level by measures which include the national psychiatric morbidity survey; reduction in suicide rates; access to psychological therapies; access to single sex accommodation; reduction in number of prisoners awaiting transfer to hospital; implementation of the ‘caring for carers’ action plans; and reduction in readmission rates.

- 26. 26 The proposed outcome indicators for cases of severe mental illness include the prevalence of severe illness; the number of patients discharged from follow-up; CPA plans signed by service users; the incidence of serious physical injury; in- patient admissions; patients lost to follow-up; admissions of longer than 90 days duration; the prevalence of side effects from antipsychotics; user satisfaction measures; mortality amongst people with severe illness; and the number of homicides. THE NHS PLAN (July 2000) The NHS Plan represents the Government’s blueprint for the NHS. The money ‘newly allocated’ to the NHS plan includes over £300 million by 2003/04 for the mental health National Service Framework. Under the plan, the Department of Health’s role is to champion the interests of patients by applying pressure and support, setting priorities and developing standards. This involves monitoring performance, putting in place a system of inspection, and providing back-up to assist modernisation and correct failure. Important elements of the plan are national service frameworks (NSFs); the establishment of care trusts; a new concordat with the private and voluntary sector and the NHS; and the establishment of several new public or departmental bodies. CARE STANDARDS ACT 2000 (July 2000) The main purpose of the Care Standards Act 2000 was to reform the regulatory system for care services in England and Wales.20 CARE STANDARDS ACT 2000 Key reforms 1 A new regulatory body for social care and private health care services in England, known as the National Care Standards Commission; 2 A new council responsible for registering social care workers, setting standards for social care work, and regulating the education and training of social workers (General Social Care Council (GSCC) for England); 3 Reform of the regulation of childminders and day care provision for young children; and 4 Maintenance of a list of individuals who are considered unsuitable to work with vulnerable adults. The new arrangements replace those in the Registered Homes Act 1984, which are repealed in their entirety, and those in the Children Act 1989 which deal with the regulation of voluntary and registered children’s homes. The Act also makes provision for the abolition of the Central Council for Education and Training in Social Work (CCETSW), which previously regulated social work training. For the first time, local authorities are required to meet the same standards as independent sector providers and a register of social care staff will be maintained.

- 27. 27 HEALTH & SOCIAL CARE ACT 2001 (May 2001) The Health & Social Care Act 2001 included a further raft of reforms concerning both health and social care. HEALTH & SOCIAL CARE ACT 2001 Key reforms 1. Further provisions concerning partnership arrangements 2. Establishment of Care Trusts 3. Public-private partnerships 4. New provisions concerning patient information 5. Extension of prescribing rights 6. New provisions concerning long-term care 7. Various changes to Part II services Further provisions concerning partnership arrangements Where NHS services or social services are failing, section 46 provides for the Secretary of State to direct that local partners enter into partnership arrangements and/or pooled funding arrangements. Creation of care trusts The 2001 Act provides for the establishment of Care Trusts, which are intended to provide for a high level of integration between health and local authority services. Such trusts may be established either by dissolving an existing NHS organisation or by amending the establishment order of the existing NHS organisation. The two basic models are: • Incorporating social care within (specialist mental health) NHS trusts. This involves NHS Trusts taking on social care service provision and (where delegated by the local PCT or Health Authority) some commissioning. • PCTs taking on mental health and social care (the ‘PCT+ model’). Here, a PCT would take on certain specialist mental health and social care services and commission the remainder. A care trust can be imposed by the Secretary of State following failures in joint working. Public private partnerships Section 4 inserts a new section 96C into the 1977 Act to provide for the Secretary of State to participate in public-private partnerships with companies that provide facilities or services to persons or bodies carrying out NHS functions.21 These new powers can be delegated to Health Authorities and, through them, to PCTs and Special Health Authorities. The first use of this new power is the establishment of NHS LIFT (NHS Local Improvement Finance Trust), which will invest in primary care premises.

- 28. 28 Patient information Section 60 of the 2001 Act enables the Secretary of State to require or permit patient information to be shared for medical purposes, where he considers that this is in the interests of improving patient care or in the public interest. This will make it possible for confidential patient information to be lawfully processed without informed consent in order to support prescribed activities such as cancer registries. Regulations can only provide for the processing of patient information for medical purposes where there is a benefit to patient care or where this is in the public interest, and where there is no reasonably practicable alternative. Patient Information Advisory Group Section 61 requires the Secretary of State to establish a committee known as the Patient Information Advisory Group. The work of the Advisory Group is intended to provide an additional safeguard for patients as regards use of the power provided by section 60. It is envisaged that the Advisory Group’s views will be sought on a range of issues pertaining to the confidentiality of patient information and standards of processing such information. Sharing information with patients Regulations may also require specified communications about patients to be disclosed to the patients by NHS bodies. Such regulations are intended to support the NHS Plan commitment that clinicians will in the future be required to share information about patients with them. Services for people with mental illness Section 62 amends section 11 of the Disabled Persons (Services, Consultation and Representation) Act 1986, so that the Secretary of State must produce separate annual reports on the development of health and social services for people with mental illness and people with learning disability. There will no longer be a statutory requirement to include information on the number of people receiving treatment for mental illness/learning disability as in- patients in hospitals. Extension of prescribing rights Section 63 enables prescribing rights to be extended to registered health professionals who do not already have them.22 A new advisory group will consider whether prescribing rights should be granted to any additional group of health professionals, and advise the Secretary of State on any conditions or limitations that should be applied to their prescribing. One of the effects of this policy may be to remove the need for routine visits to a GP for continuing care. For example, physiotherapists may be given prescribing rights for certain drugs, such as anti-inflammatories. Long term care/social care Section 49 excludes nursing care from community care services, so that people in nursing homes (including those who make their own arrangements for nursing home accommodation) will not be required to contribute towards the cost of their nursing care. It is estimated that around 35,000 people who are currently paying for nursing care will receive free nursing care through the NHS.

- 29. 29 The section also removes the right of a local authority to provide or arrange nursing care by a registered nurse.23 It is intended that the NHS will provide or arrange nursing care by registered nurses, and such care will (in accordance with the 1977 Act) be free of charge. Abolition of preserved rights Section 50 provides for the transfer to local authorities of responsibility for providing community care services to ‘preserved rights recipients’; that is, for arranging and meeting the care needs of people who have until now had their long-term care funded through preserved rights to central government benefits (income support and jobseeker’s allowance).24 The entitlement of these people to higher rates of income support and jobseeker’s allowance will be terminated.25 The new arrangements will require local authorities to: • identify those people with preserved rights (by working with the Department of Social Security, which is given power to disclose relevant information); • carry out appropriate care assessments; • secure community care services from the appointed day for those who have until now enjoyed preserved rights in relation to their accommodation. Any private arrangements which an individual has made with a residential home will terminate on the day from which s/he is provided with the community care services secured by the local authority.26 Measures to increase availability of Part III accommodation At present, local authorities may refuse to support a person who has capital in excess of £18,500 and the capacity to make their own arrangements. Section 53 enables the Secretary of State to specify in regulations certain capital that is to be ignored by local authorities when determining whether care and attention is ‘otherwise available’. The intention is that more people will be able to take up the offer of a charge against their home to pay for their accommodation. Funding by resident of more expensive accommodation At present, people provided with accommodation by local authorities cannot themselves pay the extra money required for them to be provided with more expensive accommodation than the local authority will pay for. In other words, they cannot use any assets ignored by the means test. Section 54 enables regulations to be made that enable both residents and third parties to make additional payments, so that a resident can enter more expensive accommodation than that which the authority would normally pay for in respect of a person with the same needs. Power for local authorities to take charges on land instead of contributions Section 55 enables local authorities to enter into deferred payments agreements. The effect is to make it possible for people going into care to defer selling their homes in order to pay for their care. Instead the resident will grant the authority a charge over land in respect of such payments. Interest is not to be charged for an exempt period, but a local authority may charge interest after that period at a reasonable rate set out in directions given by the Secretary of State. In effect, the local authority will make a loan to the resident, and recover the money either from the estate when the resident dies, or from the resident if s/he decides to make a full repayment during her/his lifetime.