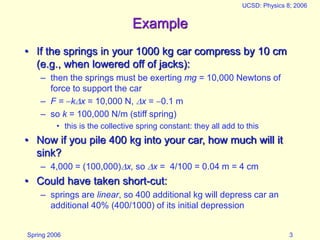

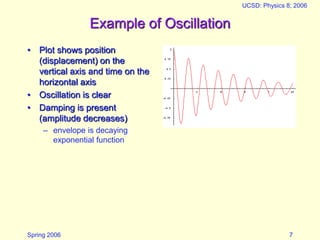

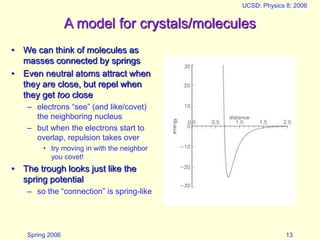

This document discusses springs and restoring forces. It provides examples of how springs exert a restoring force proportional to their displacement and explains how this can be modeled using a spring constant. It then discusses how springs can store energy and oscillate, explaining that the potential energy stored in a spring is 1/2kx^2. It provides an example of oscillation and discusses factors like frequency, resonance, and damping. It proposes a model using springs to represent molecular bonds and describes how this can represent thermal vibrations within materials.