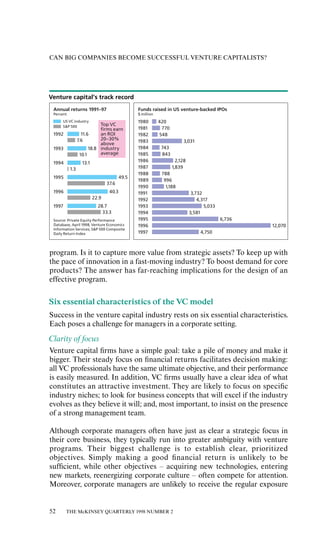

The document discusses the challenges and strategies for large companies attempting to adopt the venture capital (VC) model for innovation and growth. While big companies have the potential to apply VC successfully, they often struggle due to differences in culture, decision-making processes, and contact networks in comparison to traditional VC firms. Successful adoption requires a clear understanding of objectives and tailored approaches that align with the companies' specific capabilities and circumstances.