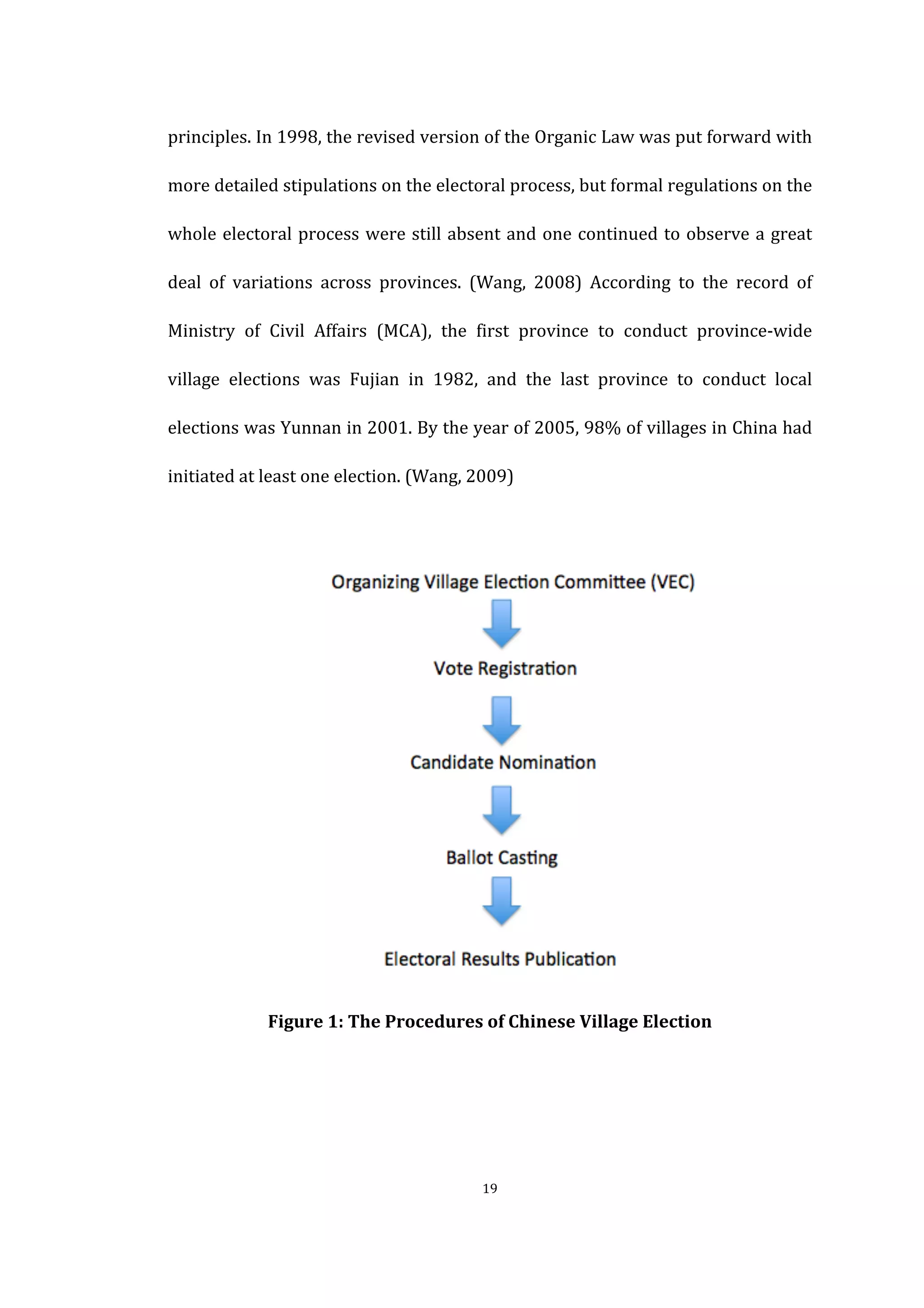

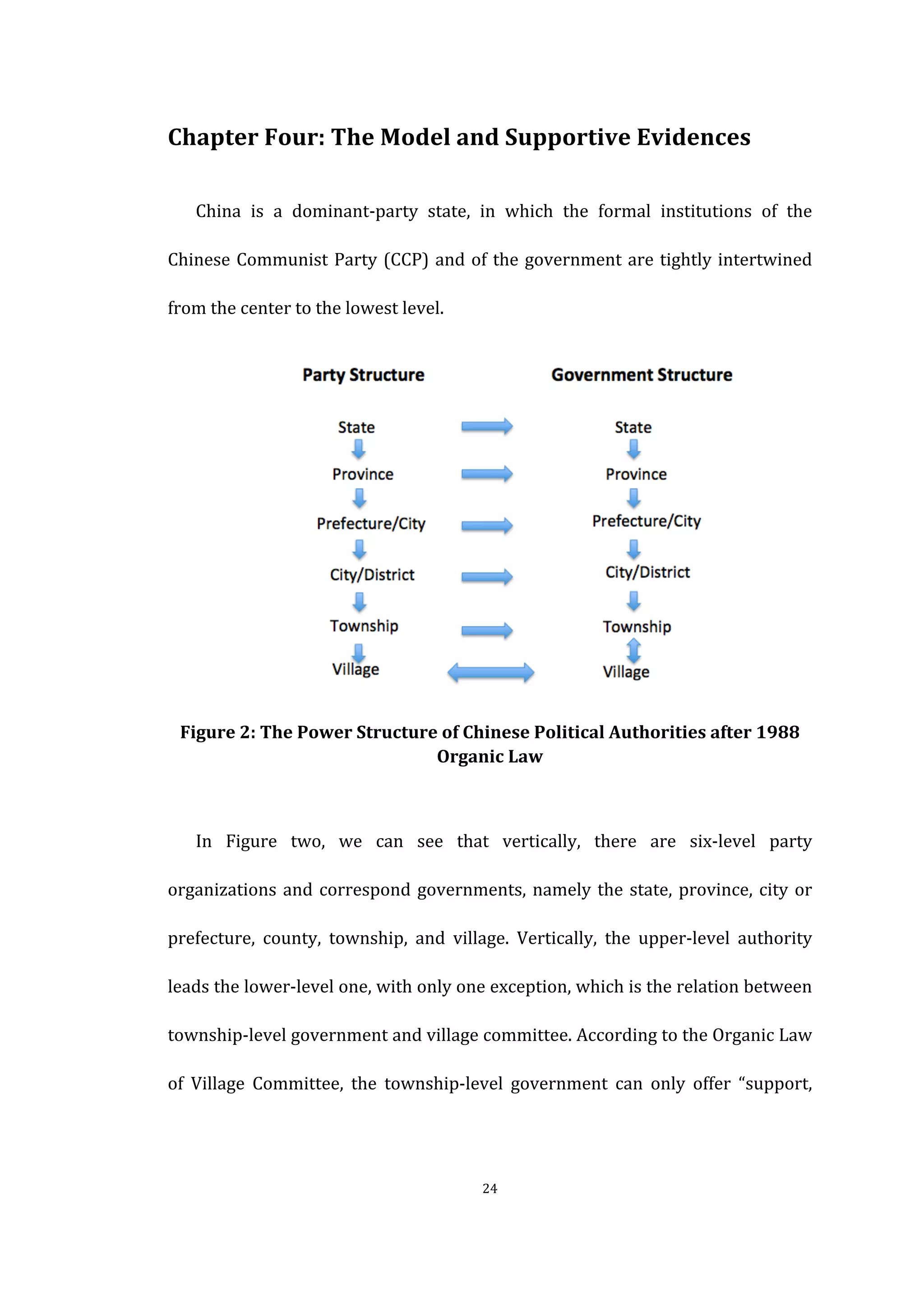

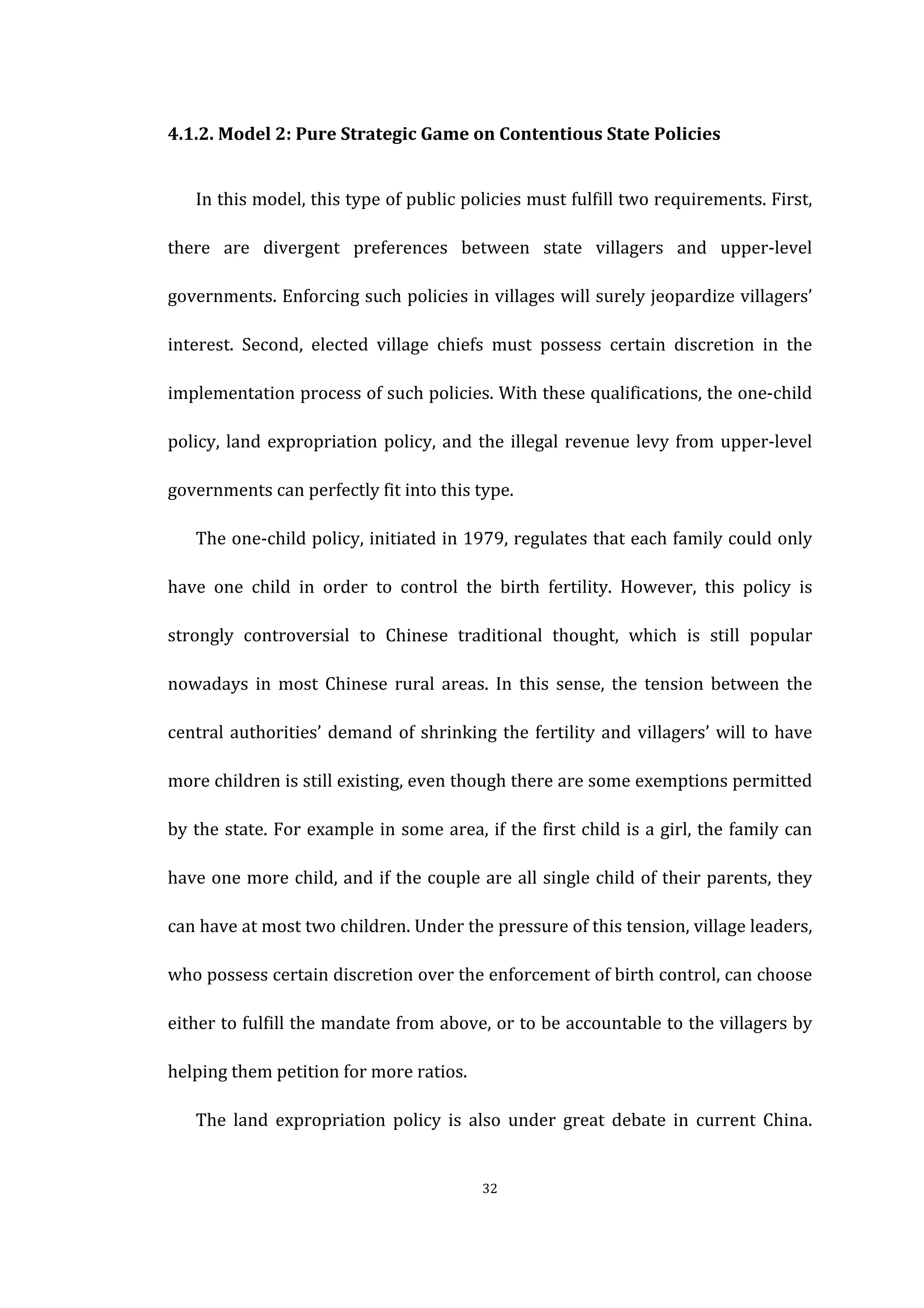

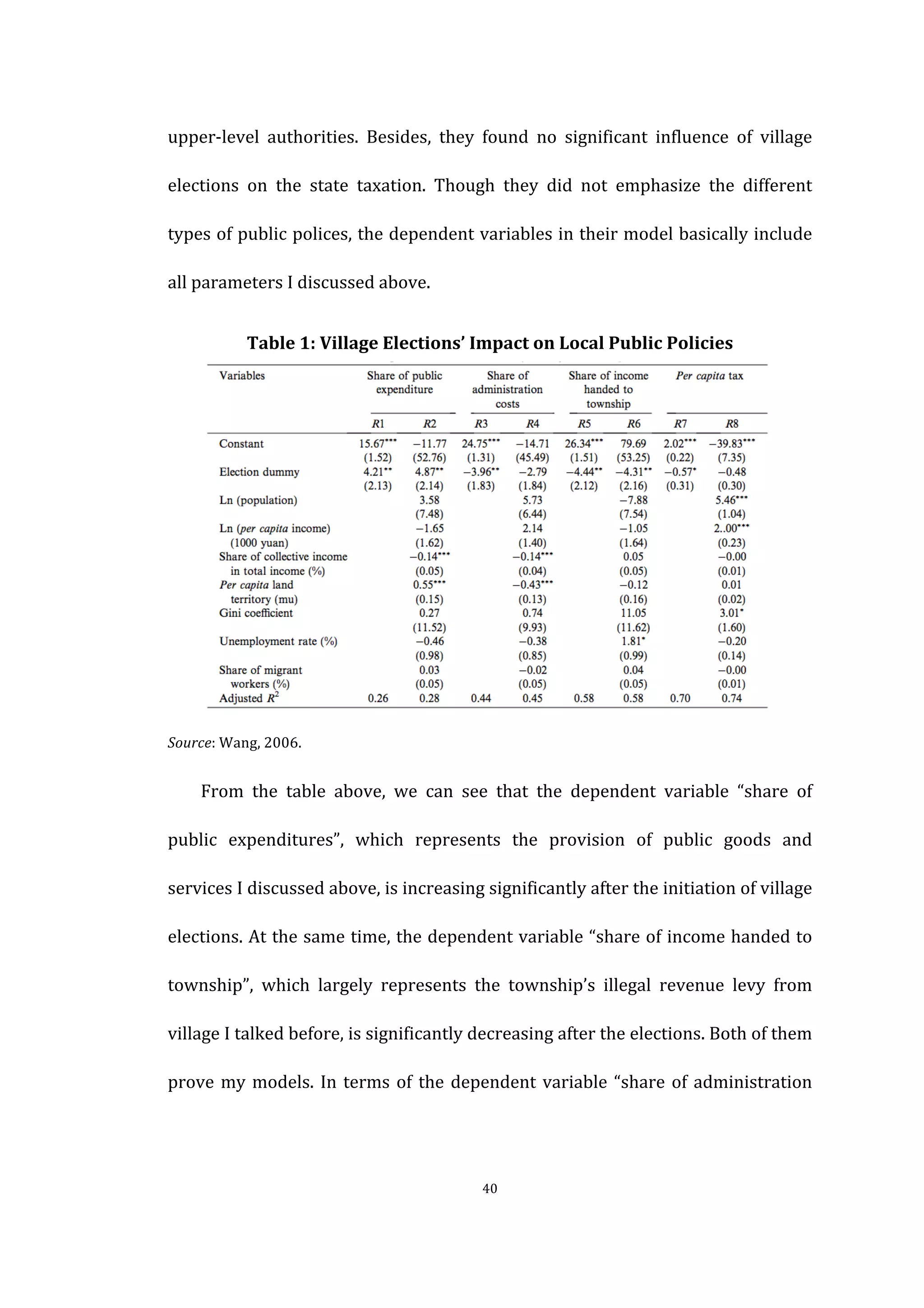

This document is a thesis submitted by Zilong Li to Duke University in partial fulfillment of a Master's degree in political science. It examines the power-sharing struggle that has emerged in Chinese village elections between local Communist Party branches and elected village committees. The thesis develops formal models to explain this puzzle and analyzes the "Qingxian Model" case study, which resurrected village assemblies to reconcentrate power in the party.