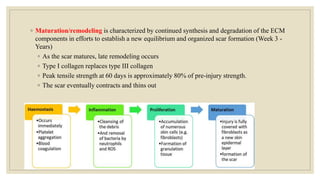

The document explores the management of ulcers, emphasizing the importance of understanding skin anatomy and the wound healing process, including the four phases: hemostasis, inflammation, proliferation, and maturation/remodeling. Clinicians are guided on approach and assessment of wounds, distinguishing between acute and chronic wounds, and addressing confounding factors that impede healing. It also highlights the risk factors and treatment considerations for necrotizing soft tissue infections, underscoring the urgent need for surgical intervention and prompt antimicrobial therapy.

![◦ References

◦ 1.Afonso AC, Oliveira D, Saavedra MJ, Borges A, Simões M. Biofilms in Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Impact, Risk Factors and Control Strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jul 31;22(15) [PubMed]

◦ 2.Tsegay F, Elsherif M, Butt H. Smart 3D Printed Hydrogel Skin Wound Bandages: A Review. Polymers (Basel). 2022 Mar 03;14(5) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 3.Bonifant H, Holloway S. A review of the effects of ageing on skin integrity and wound healing. Br J Community Nurs. 2019 Mar 01;24(Sup3):S28-S33. [PubMed]

◦ 4.Veith AP, Henderson K, Spencer A, Sligar AD, Baker AB. Therapeutic strategies for enhancing angiogenesis in wound healing. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019 Jun;146:97-125. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 5.Leavitt T, Hu MS, Marshall CD, Barnes LA, Lorenz HP, Longaker MT. Scarless wound healing: finding the right cells and signals. Cell Tissue Res. 2016 Sep;365(3):483-93. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 6.Lindholm C, Searle R. Wound management for the 21st century: combining effectiveness and efficiency. Int Wound J. 2016 Jul;13 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):5-15. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 7.Jørgensen SF, Nygaard R, Posnett J. Meeting the challenges of wound care in Danish home care. J Wound Care. 2013 Oct;22(10):540-2, 544-5. [PubMed]

◦ 8.Valentine KP, Viacheslav KM. Bacterial flora of combat wounds from eastern Ukraine and time-specified changes of bacterial recovery during treatment in Ukrainian military hospital. BMC Res

Notes. 2017 Apr 07;10(1):152. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 9.Jirawitchalert S, Mitaim S, Chen CY, Patikarnmonthon N. Cotton Cellulose-Derived Hydrogel and Electrospun Fiber as Alternative Material for Wound Dressing Application. Int J

Biomater. 2022;2022:2502658. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 10.Lumbers M. TIMERS: undertaking wound assessment in the community. Br J Community Nurs. 2019 Dec 01;24(Sup12):S22-S25. [PubMed]

◦ 11.Yousef H, Alhajj M, Sharma S. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): Nov 14, 2022. Anatomy, Skin (Integument), Epidermis. [PubMed]

◦ 12.Kechichian E, Ezzedine K. Vitamin D and the Skin: An Update for Dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018 Apr;19(2):223-235. [PubMed]

◦ 13.Wilkinson HN, Hardman MJ. Wound healing: cellular mechanisms and pathological outcomes. Open Biol. 2020 Sep;10(9):200223. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 14.Rodrigues M, Kosaric N, Bonham CA, Gurtner GC. Wound Healing: A Cellular Perspective. Physiol Rev. 2019 Jan 01;99(1):665-706. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 15.Guo S, Dipietro LA. Factors affecting wound healing. J Dent Res. 2010 Mar;89(3):219-29. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 16.Raziyeva K, Kim Y, Zharkinbekov Z, Kassymbek K, Jimi S, Saparov A. Immunology of Acute and Chronic Wound Healing. Biomolecules. 2021 May 08;11(5) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 17.O'Connell RL, Rusby JE. Anatomy relevant to conservative mastectomy. Gland Surg. 2015 Dec;4(6):476-83. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 18.Andersson T, Ertürk Bergdahl G, Saleh K, Magnúsdóttir H, Stødkilde K, Andersen CBF, Lundqvist K, Jensen A, Brüggemann H, Lood R. Common skin bacteria protect their host from oxidative stress

through secreted antioxidant RoxP. Sci Rep. 2019 Mar 05;9(1):3596. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 19.Losquadro WD. Anatomy of the Skin and the Pathogenesis of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017 Aug;25(3):283-289. [PubMed]

◦ 20.Slominski AT, Manna PR, Tuckey RC. On the role of skin in the regulation of local and systemic steroidogenic activities. Steroids. 2015 Nov;103:72-88. [PMC free article]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/managementofulcersaa-231008090234-eb41d71a/85/MANAGEMENT_OF_ULCERS-aa-pptx-71-320.jpg)

![◦ 21.Rothe K, Tsokos M, Handrick W. Animal and Human Bite Wounds. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015 Jun 19;112(25):433-42; quiz 443. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 22.Li S, Mohamedi AH, Senkowsky J, Nair A, Tang L. Imaging in Chronic Wound Diagnostics. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2020 May 01;9(5):245-263. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 23.Sen CK. Human Wound and Its Burden: Updated 2020 Compendium of Estimates. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2021 May;10(5):281-292. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 24.Liu X, Zhang H, Cen S, Huang F. Negative pressure wound therapy versus conventional wound dressings in treatment of open fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J

Surg. 2018 May;53:72-79. [PubMed]

◦ 25.Bowers S, Franco E. Chronic Wounds: Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Feb 01;101(3):159-166. [PubMed]

◦ 26.Yao K, Bae L, Yew WP. Post-operative wound management. Aust Fam Physician. 2013 Dec;42(12):867-70. [PubMed]

◦ 27.Johnston BR, Ha AY, Kwan D. Surgical Management of Chronic Wounds. R I Med J (2013). 2016 Feb 01;99(2):30-3. [PubMed]

◦ 28.Ricci JA, Bayer LR, Orgill DP. Evidence-Based Medicine: The Evaluation and Treatment of Pressure Injuries. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Jan;139(1):275e-286e. [PubMed]

◦ 29.Quain AM, Khardori NM. Nutrition in Wound Care Management: A Comprehensive Overview. Wounds. 2015 Dec;27(12):327-35. [PubMed]

◦ 30.Sharma A, Gupta V, Shashikant K. Optimizing Management of Open Fractures in Children. Indian J Orthop. 2018 Sep-Oct;52(5):470-480. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 31.Decruz J, Antony Rex RP, Khan SA. Epidemiology of inpatient tibia fractures in Singapore - A single centre experience. Chin J Traumatol. 2019 Apr;22(2):99-102. [PMC free article]

[PubMed]

◦ 32.Silluzio N, De Santis V, Marzetti E, Piccioli A, Rosa MA, Maccauro G. Clinical and radiographic outcomes in patients operated for complex open tibial pilon fractures. Injury. 2019

Jul;50 Suppl 2:S24-S28. [PubMed]

◦ 33.Zierenberg García C, Beaton Comulada D, Pérez López JC, Lamela Domenech A, Rivera Ortiz G, González Montalvo HM, Reyes-Martínez PJ. Acute Shortening and re-lengthening in

the management of open tibia fractures with severe bone of 14 CMS or more and extensive soft tissue loss. Bol Asoc Med P R. 2016;108(1):91-94. [PubMed]

◦ 34.Harries RL, Bosanquet DC, Harding KG. Wound bed preparation: TIME for an update. Int Wound J. 2016 Sep;13 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):8-14. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 35.Martin P, Nunan R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of repair in acute and chronic wound healing. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Aug;173(2):370-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

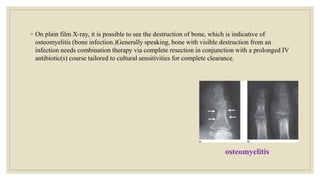

◦ 36.Giurato L, Meloni M, Izzo V, Uccioli L. Osteomyelitis in diabetic foot: A comprehensive overview. World J Diabetes. 2017 Apr 15;8(4):135-142. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 37.Ugwu E, Anyanwu A, Olamoyegun M. Ankle brachial index as a surrogate to vascular imaging in evaluation of peripheral artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMC

Cardiovasc Disord. 2021 Jan 06;21(1):10. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 38.Barchitta M, Maugeri A, Favara G, Magnano San Lio R, Evola G, Agodi A, Basile G. Nutrition and Wound Healing: An Overview Focusing on the Beneficial Effects of Curcumin. Int

J Mol Sci. 2019 Mar 05;20(5) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 39.Zinder R, Cooley R, Vlad LG, Molnar JA. Vitamin A and Wound Healing. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019 Dec;34(6):839-849. [PubMed]

◦ 40.Leow JJ, Lingam P, Lim VW, Go KT, Chiu MT, Teo LT. A review of stab wound injuries at a tertiary trauma centre in Singapore: are self-inflicted ones less severe? Singapore Med

J. 2016 Jan;57(1):13-7. [PMC free article](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/managementofulcersaa-231008090234-eb41d71a/85/MANAGEMENT_OF_ULCERS-aa-pptx-72-320.jpg)

![◦ 41.Nawijn F, Hietbrink F, Peitzman AB, Leenen LPH. Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections, the Challenge Remains. Front Surg. 2021;8:721214. [PMC

free article] [PubMed]

◦ 42.Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for

distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004 Jul;32(7):1535-41. [PubMed]

◦ 43.Bonne SL, Kadri SS. Evaluation and Management of Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2017 Sep;31(3):497-511. [PMC

free article] [PubMed]

◦ 44.Rousselle P, Montmasson M, Garnier C. Extracellular matrix contribution to skin wound re-epithelialization. Matrix Biol. 2019 Jan;75-76:12-

26. [PubMed]

◦ 45.Young S. Wound assessment. Br J Community Nurs. 2019 Sep 01;24(Sup9):S5. [PubMed]

◦ 46.Rupert J, Honeycutt JD, Odom MR. Foreign Bodies in the Skin: Evaluation and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2020 Jun 15;101(12):740-

747. [PubMed]

◦ 47.Rahim K, Saleha S, Zhu X, Huo L, Basit A, Franco OL. Bacterial Contribution in Chronicity of Wounds. Microb Ecol. 2017 Apr;73(3):710-

721. [PubMed]

◦ 48.Leaper D, Assadian O, Edmiston CE. Approach to chronic wound infections. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Aug;173(2):351-8. [PubMed]

◦ 49.Kim J, Simon R. Calculated Decisions: Wound Closure Classification. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2018 Sep 01;14(Suppl 10):1-3. [PubMed]

◦ 50.Westby MJ, Dumville JC, Soares MO, Stubbs N, Norman G. Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst

Rev. 2017 Jun 22;6(6):CD011947. [PMC free article] [PubMed]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/managementofulcersaa-231008090234-eb41d71a/85/MANAGEMENT_OF_ULCERS-aa-pptx-73-320.jpg)

![◦ 51.Alsaad SM, Ross EV, Smith WJ, DeRienzo DP. Analysis of Depth of Ablation,Thermal Damage, Wound

Healing, and Wound Contraction With Erbium YAG Laser in a Yorkshire Pig Model. J Drugs

Dermatol. 2015 Nov;14(11):1245-52. [PubMed]

◦ 52.Joo J, Pourang A, Tchanque-Fossuo CN, Armstrong AW, Tartar DM, King TH, Sivamani RK, Eisen DB.

Undermining during cutaneous wound closure for wounds less than 3 cm in diameter: a randomized split

wound comparative effectiveness trial. Arch Dermatol Res. 2022 Sep;314(7):697-703. [PMC free article]

[PubMed]

◦ 53.Eggleston RB. Wound Management: Wounds with Special Challenges. Vet Clin North Am Equine

Pract. 2018 Dec;34(3):511-538. [PubMed]

◦ 54.Bradley P. Wound Exudate. Br J Community Nurs. 2018 Dec 01;23(Sup12):S28-S32. [PubMed]

◦ 55.van Asten SA, Jupiter DC, Mithani M, La Fontaine J, Davis KE, Lavery LA. Erythrocyte sedimentation

rate and C-reactive protein to monitor treatment outcomes in diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Int Wound J. 2017

Feb;14(1):142-148. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

◦ 56.AbuRahma AF, Adams E, AbuRahma J, Mata LA, Dean LS, Caron C, Sloan J. Critical analysis and

limitations of resting ankle-brachial index in the diagnosis of symptomatic peripheral arterial disease patients

and the role of diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease. J Vasc Surg. 2020 Mar;71(3):937-945. [PMC free

article] [PubMed]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/managementofulcersaa-231008090234-eb41d71a/85/MANAGEMENT_OF_ULCERS-aa-pptx-74-320.jpg)