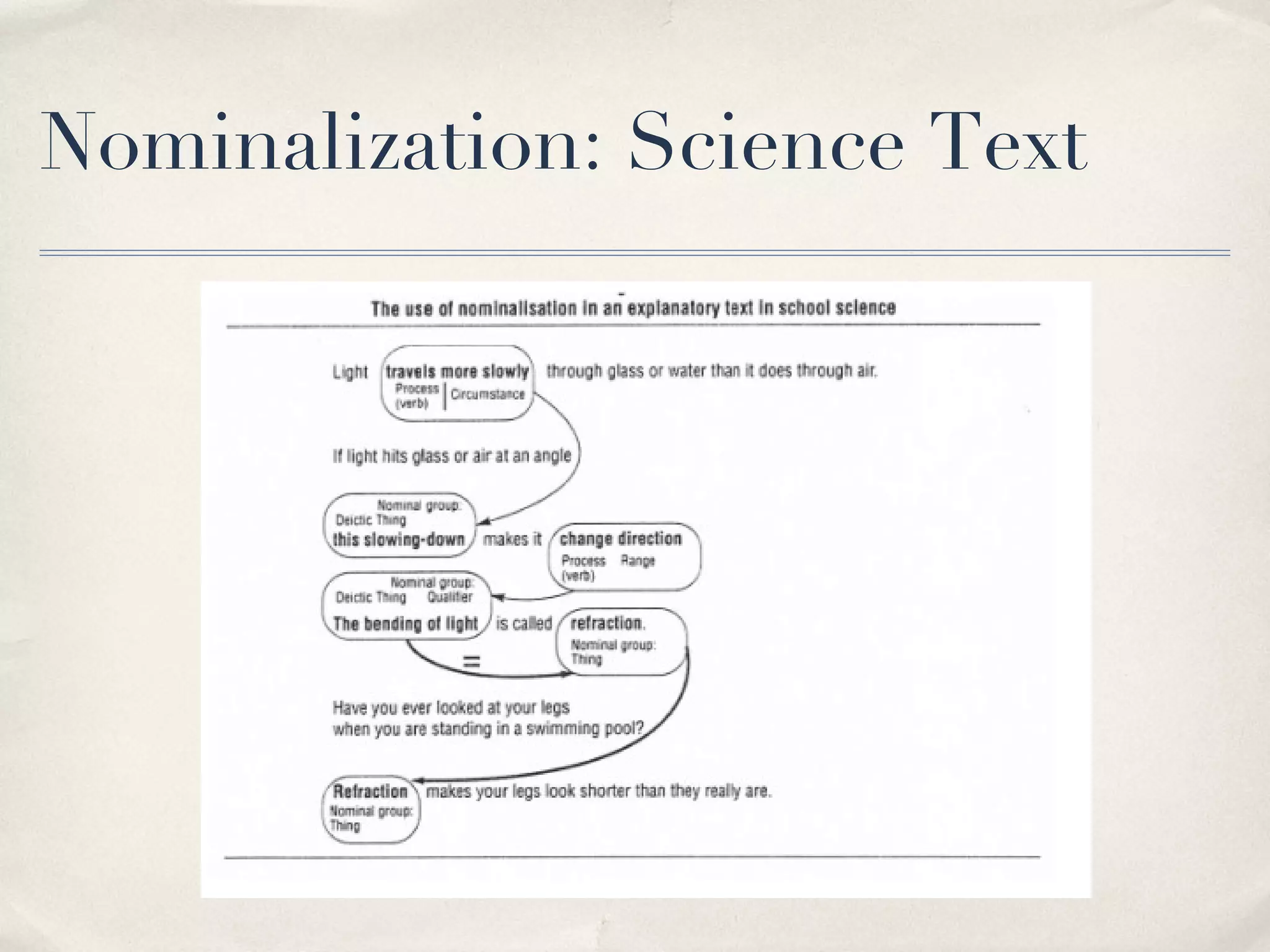

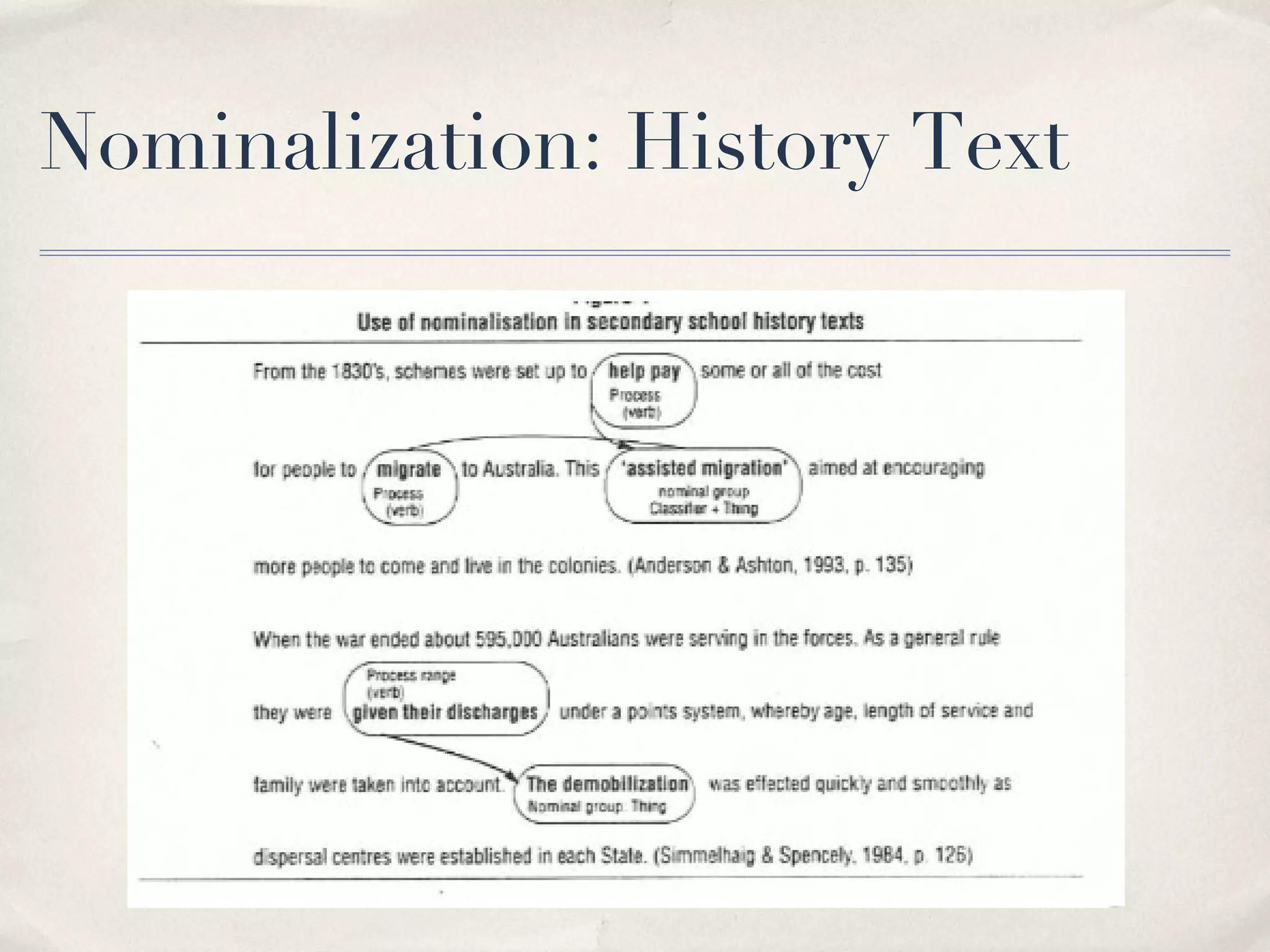

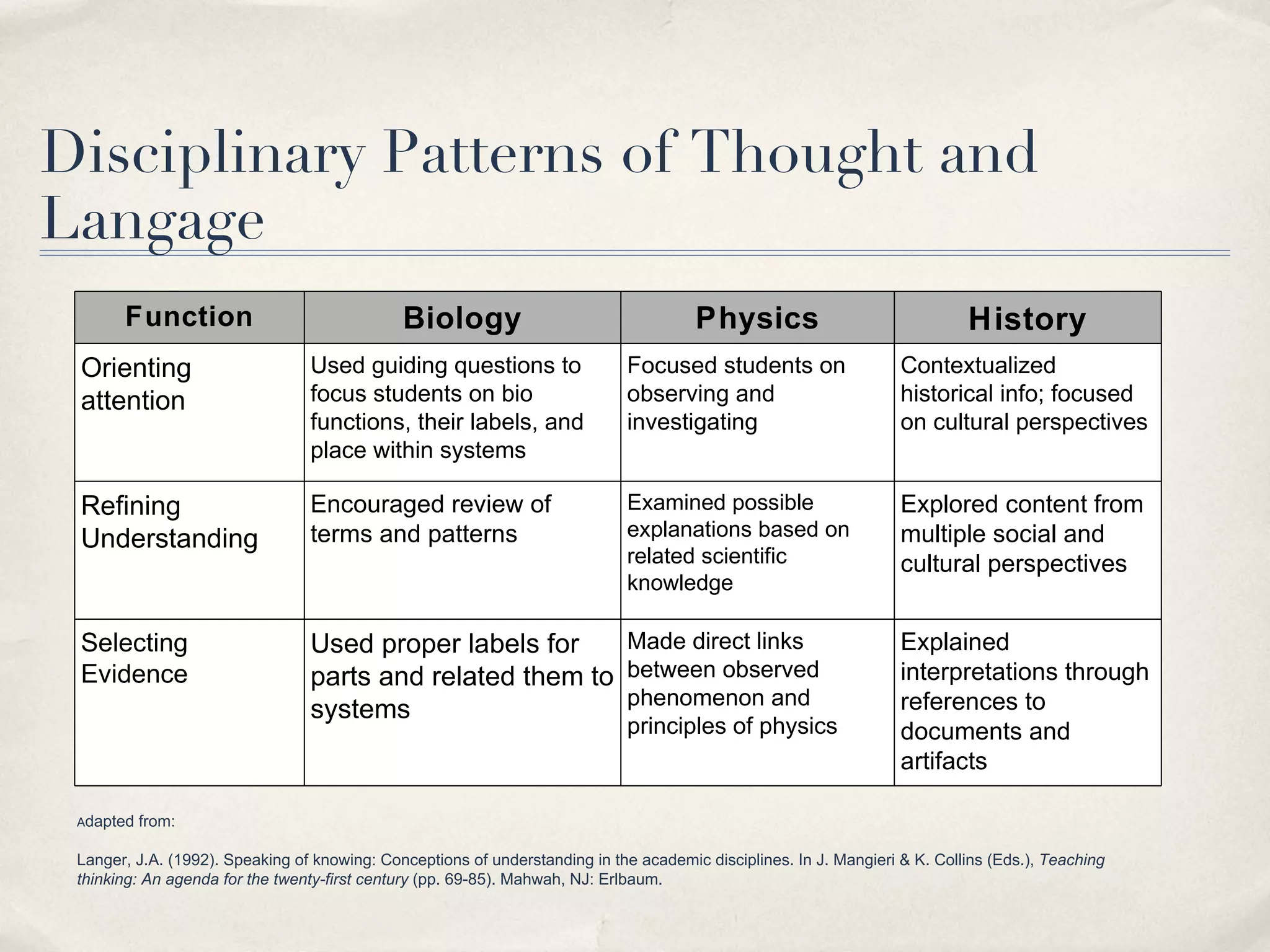

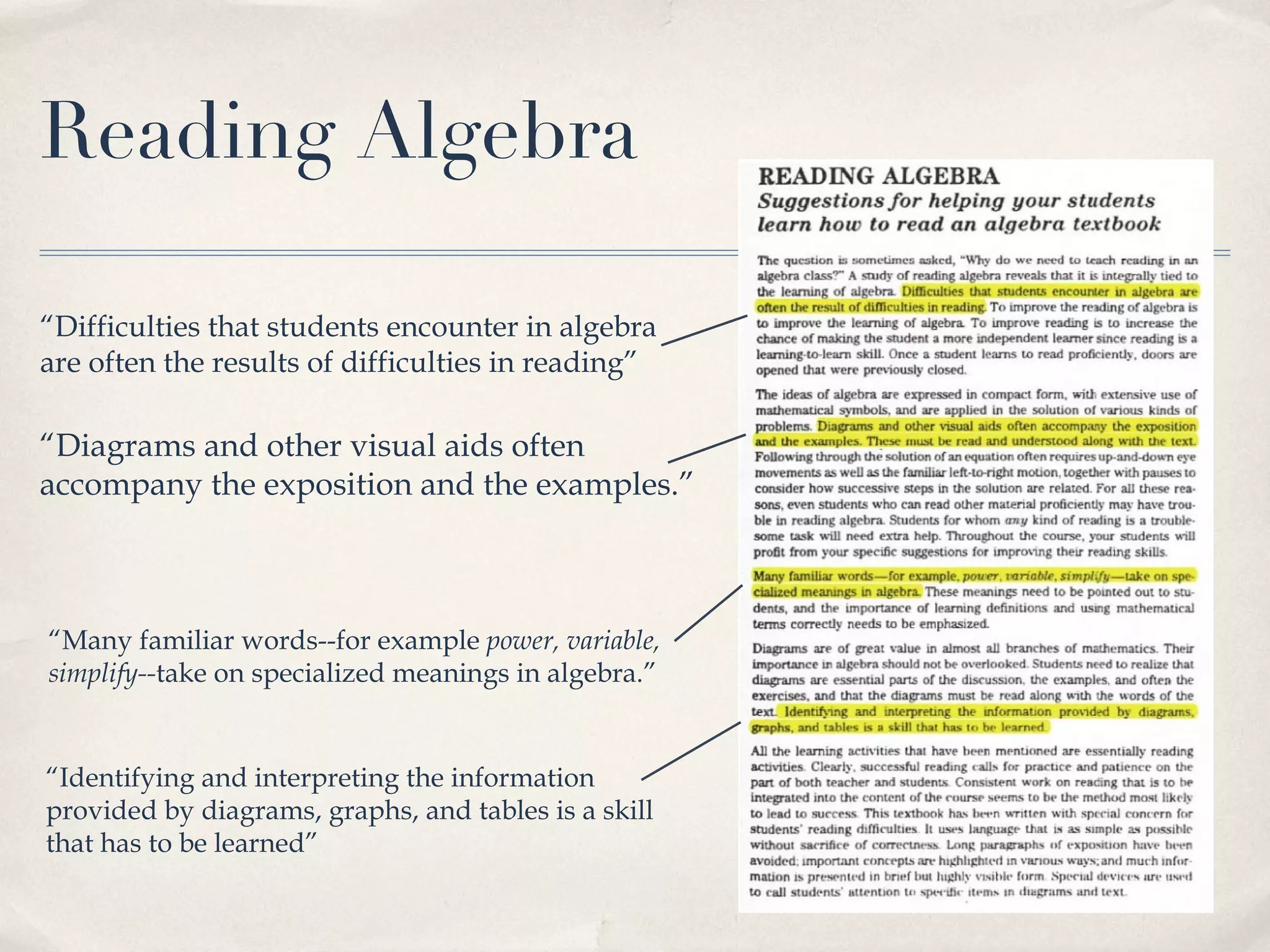

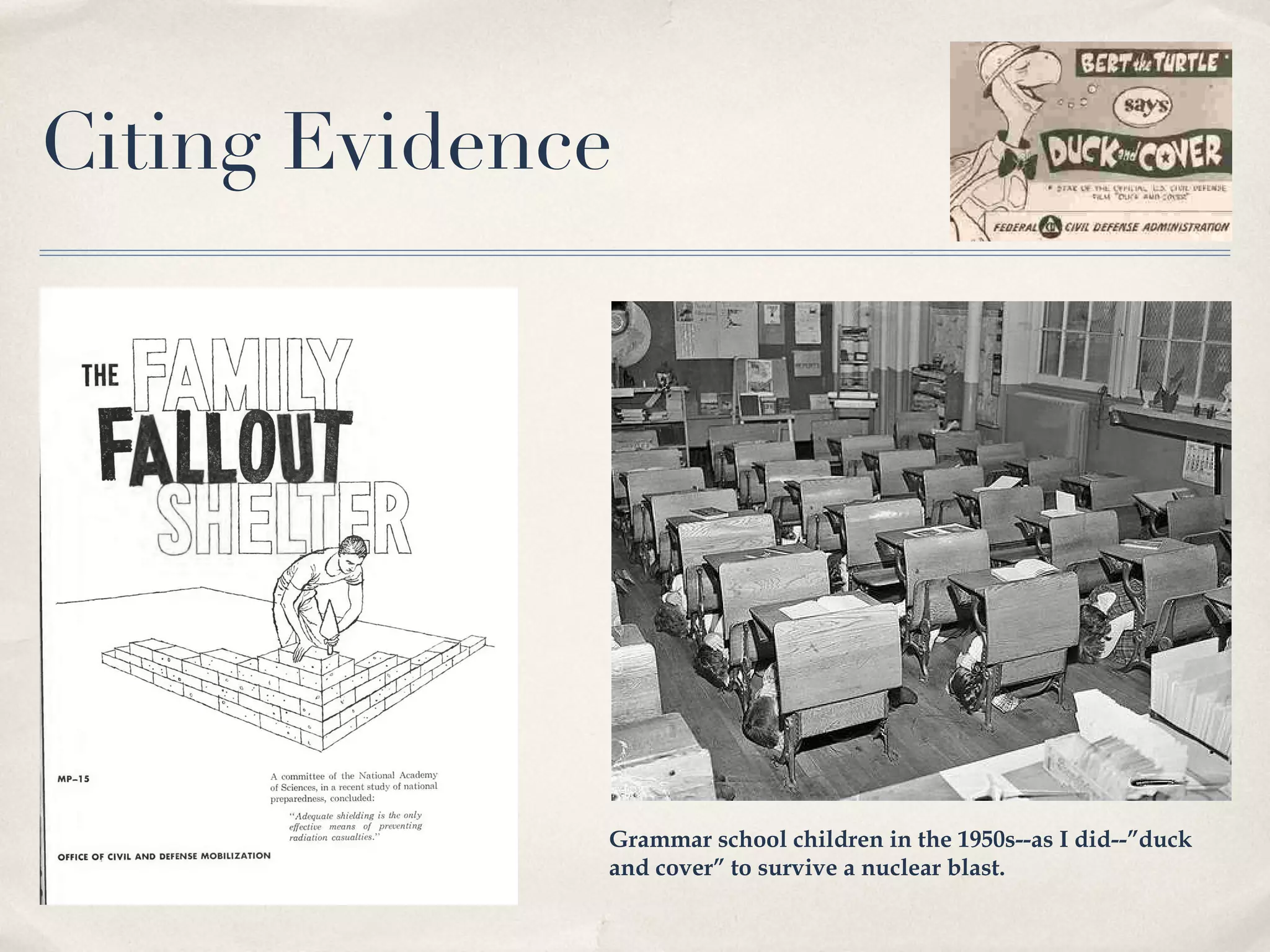

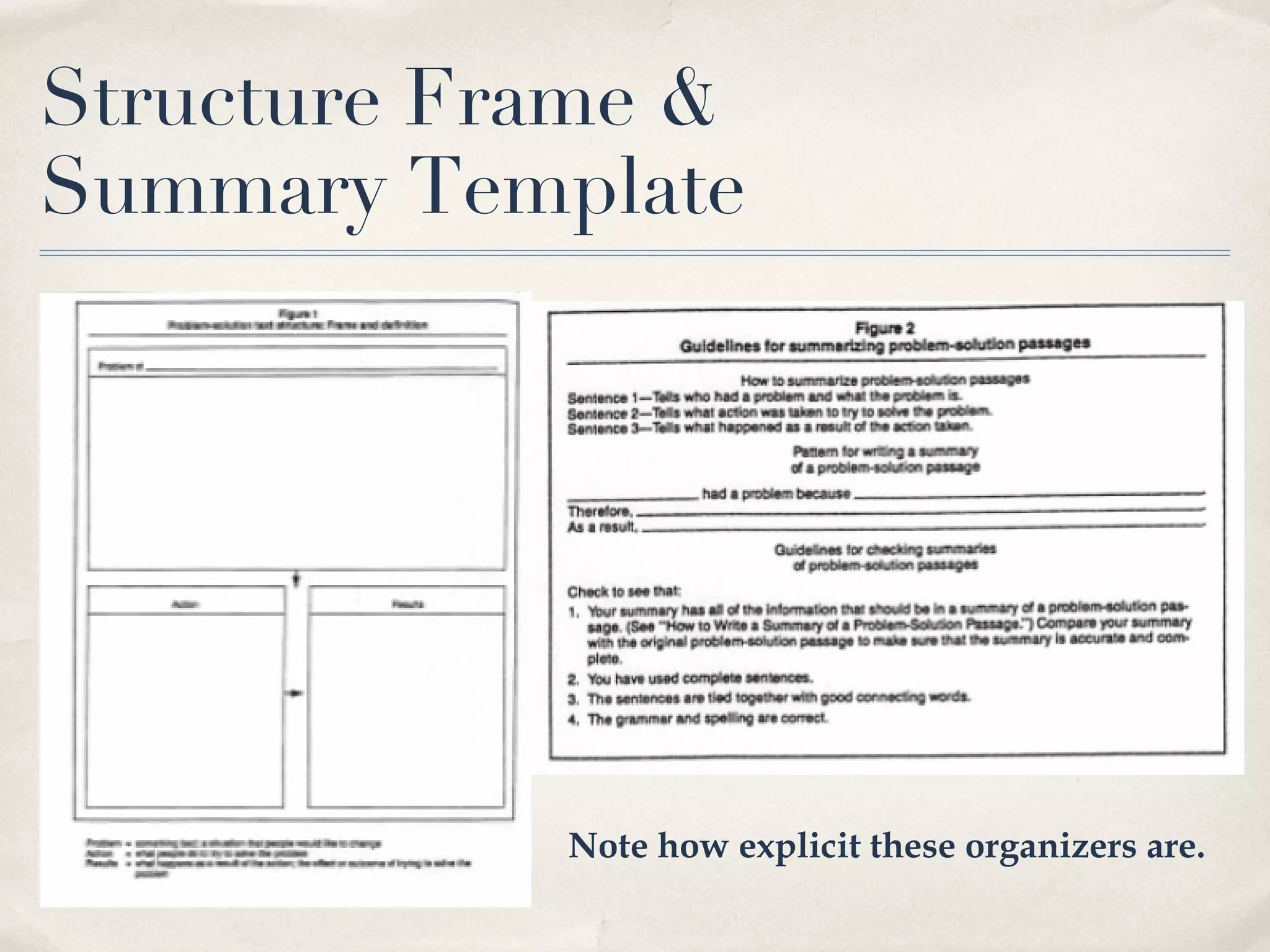

The document discusses the importance of teaching subject-matter literacy skills to struggling learners, emphasizing that understanding different academic disciplines' structures can enhance comprehension. It highlights that explicit instruction in these differences, such as vocabulary and text organization, is essential for students transitioning from 'learning to read' to 'reading to learn.' The document also provides sample activities and approaches for effectively teaching discipline-specific literacies.