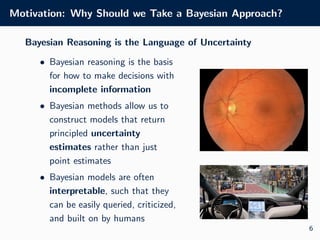

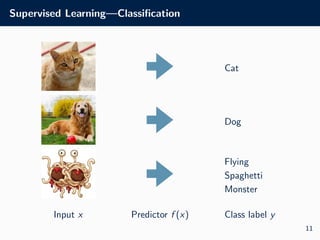

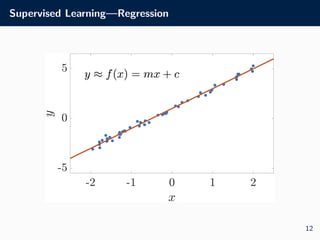

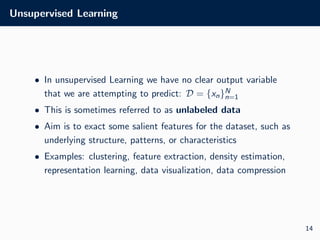

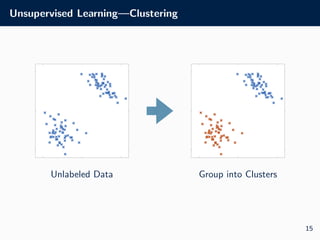

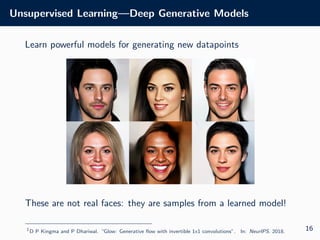

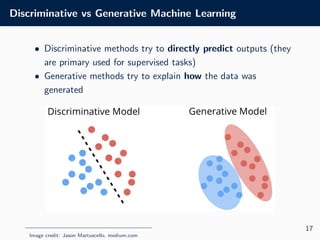

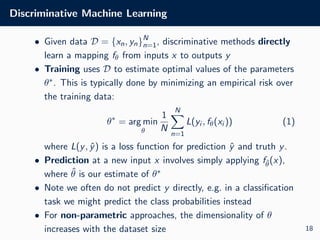

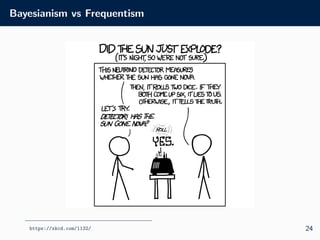

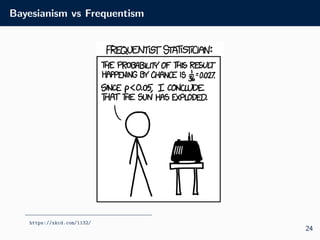

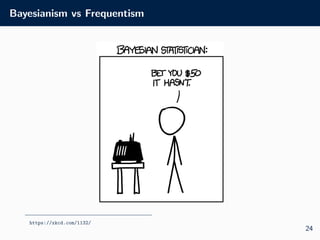

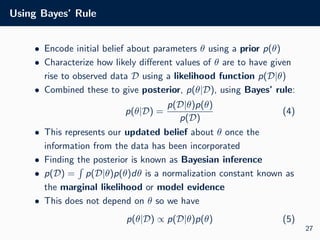

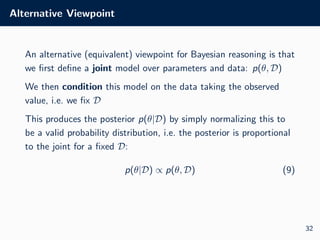

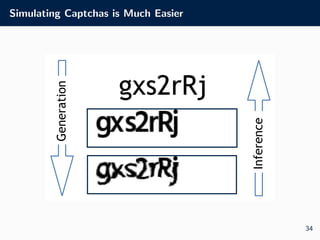

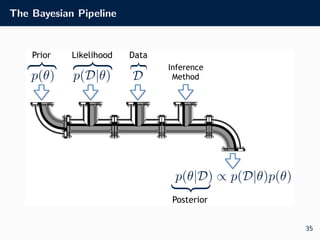

The document outlines the visual identity guidelines for the University of Oxford's logo and provides details for a machine learning course taught by Dr. Tom Rainforth. It includes information on coursework, assessments, lecture topics covering Bayesian machine learning, and explains key concepts in machine learning, including supervised and unsupervised learning. Furthermore, it emphasizes the importance of Bayesian methods in making decisions under uncertainty and provides insights into generative versus discriminative models.

![Supervised Learning

Supervised Learning

7

Datapoint

Index

x1 x2 x3 … xM

1 0.24 0.12 -0.34 … 0.98

2 0.56 1.22 0.20 … 1.03

3 -3.20 -0.01 0.21 … 0.93

… … … … … …

N 2.24 1.76 -0.47 … 1.16

y

3

2

1

…

2

Training

Data Input Features

}

}

Outputs

• Use this data to learn a predictive model fθ : X → Y (e.g. by

optimizing θ)

• Once learned, we can use this to predict outputs for new input

points, e.g. fθ([0.48 1.18 0.34 . . . 1.13]) = 2

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture1-240827120548-8a6a1e42/85/Machine-learning-with-in-the-python-lecture-for-computer-science-15-320.jpg)

![Making Predictions

• Prediction in Bayesian models is done using the posterior

predictive distribution

• This is defined by taking the expectation of a predictive model

for new data, p(D∗|θ, D), with respect to the posterior:

p(D∗

|D) =

Z

p(D∗

, θ|D)dθ (10)

=

Z

p(D∗

|θ, D)p(θ|D)dθ (11)

= Ep(θ|D)[p(D∗

|θ, D)]. (12)

• This often done dependent on an input point, i.e. we actually

calculate p(y|D, x) = Ep(θ|D)[p(y|θ, D, x)]

37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture1-240827120548-8a6a1e42/85/Machine-learning-with-in-the-python-lecture-for-computer-science-44-320.jpg)

![Recap

• Supervised learning has access to outputs, unsupervised

learning does not

• Discriminative methods try and directly make predictions,

generative methods try to explain how the data is generated

• Bayesian machine learning is a generative approach that

allows us to incorporate uncertainty and information from

prior expertise

• Bayes’ rule: p(θ|D) ∝ p(D|θ)p(θ)

• Posterior predictive: p(D∗|D) = Ep(θ|D) [p(D∗|θ, D)]

39](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture1-240827120548-8a6a1e42/85/Machine-learning-with-in-the-python-lecture-for-computer-science-46-320.jpg)