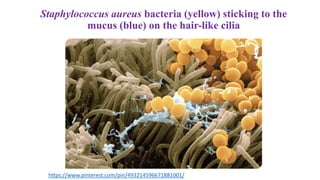

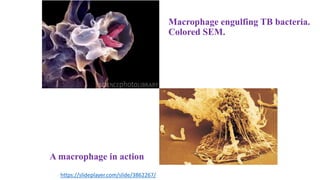

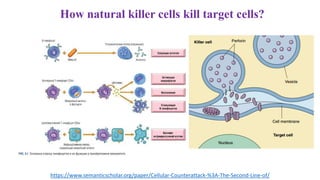

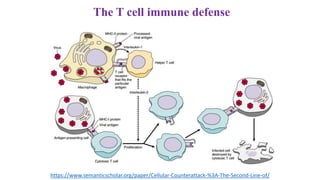

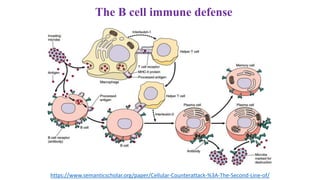

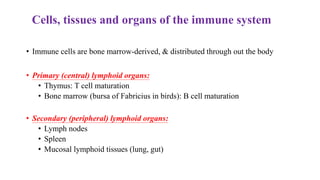

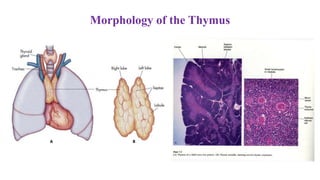

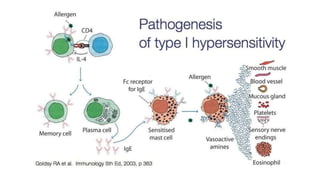

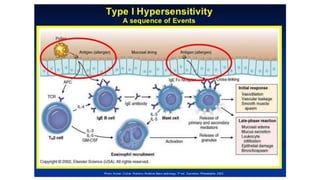

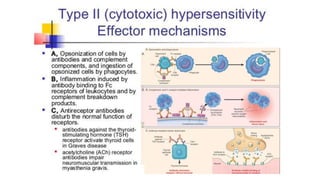

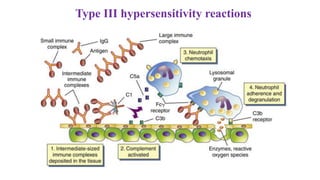

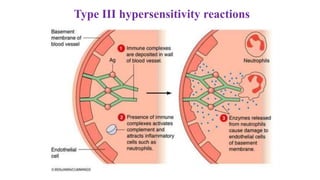

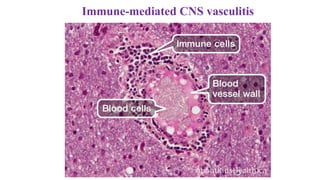

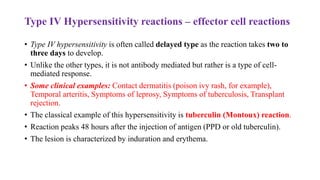

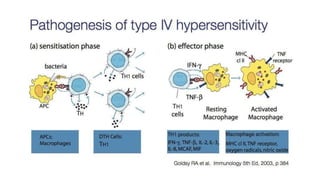

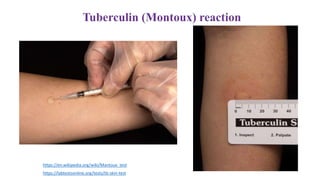

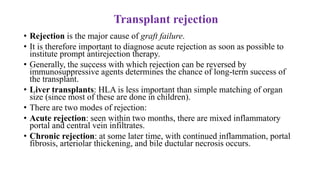

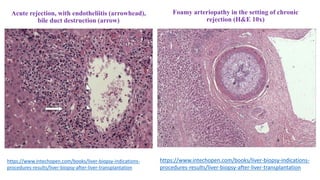

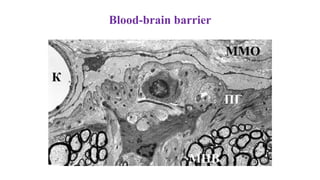

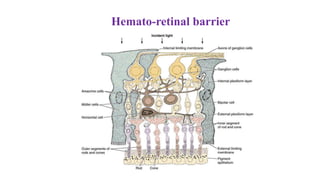

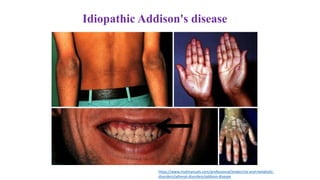

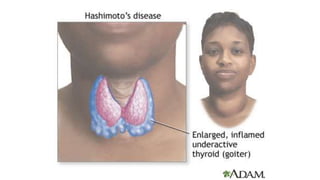

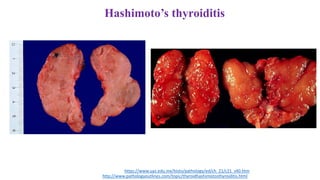

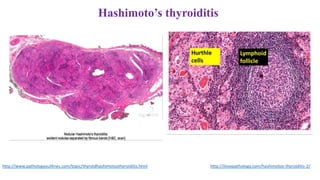

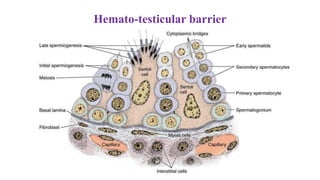

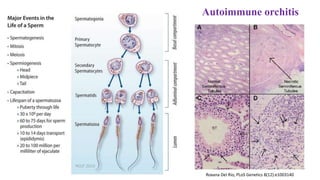

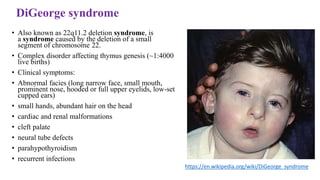

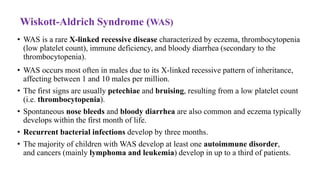

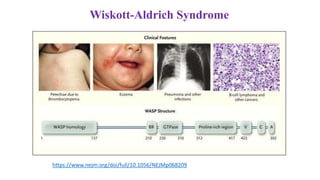

The document discusses immunopathology and compensatory-adaptive processes. It covers the body's lines of defense against pathogens including physical barriers, innate immune responses, and adaptive immune responses. It describes nonspecific defenses like skin, mucous membranes, and inflammatory response. It also details the specific immune system including B cells, T cells, antibodies, and acquired versus passive immunity. The document discusses hypersensitivity reactions, autoimmune diseases, primary immune deficiencies, and conditions like transplant rejection.