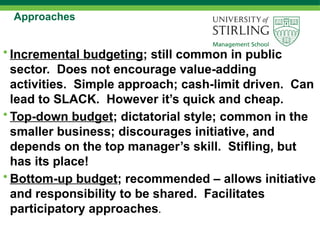

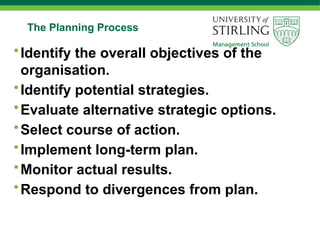

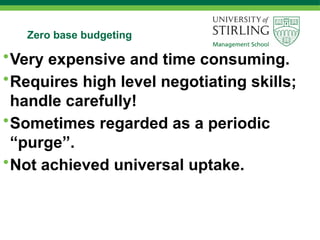

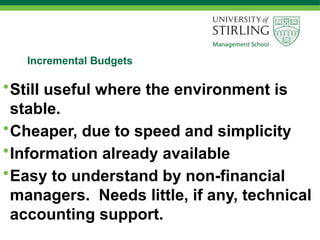

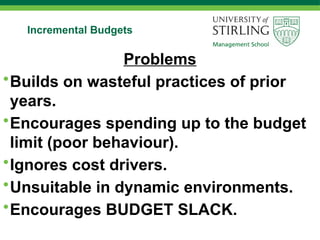

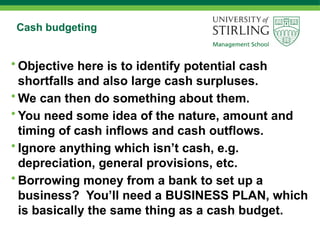

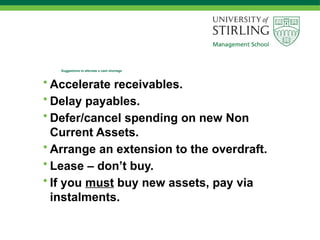

The document discusses various budgeting methods and their significance in organizational management, emphasizing the need for effective planning, coordination, communication, motivation, control, and evaluation. It outlines different budgeting approaches such as incremental, top-down, bottom-up, zero-based, and flexible budgeting, each with its advantages and drawbacks. Additionally, it highlights the behavioral implications of budgeting, including potential misbehaviors like budget slack and budget passing that can arise from performance incentives.