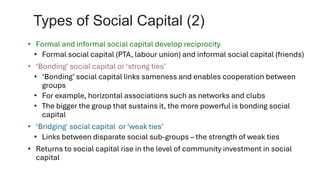

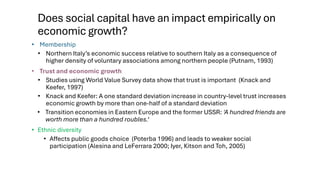

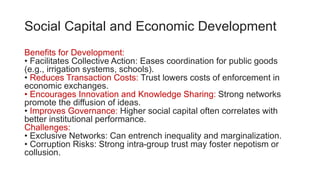

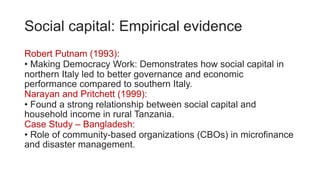

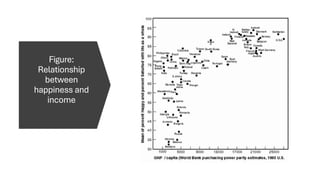

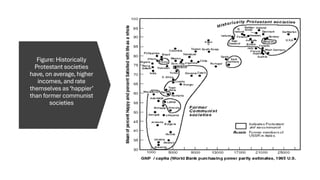

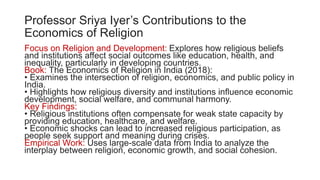

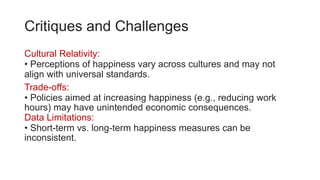

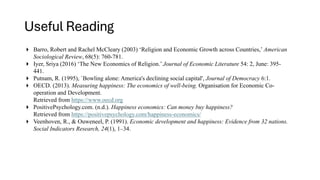

The document discusses the interconnectedness of social capital, the economics of religion, and happiness within the context of development economics, highlighting how trust, norms, and networks enhance cooperation and facilitate economic growth. It critiques the challenges in measuring social capital and religious impacts on economics while presenting empirical evidence from various case studies, including Bangladesh. Additionally, it emphasizes the importance of happiness as a broader metric of development beyond traditional economic measures like GDP.