This document provides an overview of topics covered in a lecture on mainstream economics, including:

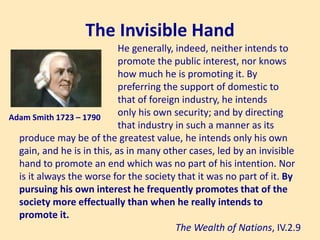

- The concept of rational economic man and how it forms the basis of mainstream economic theories.

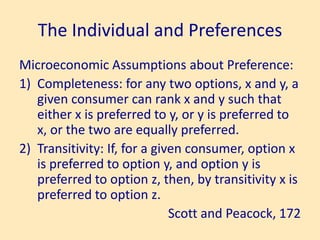

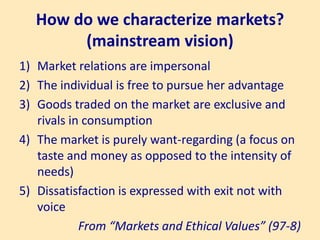

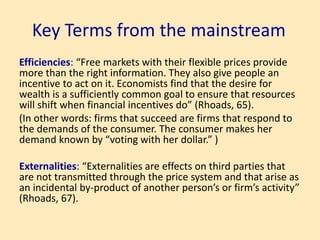

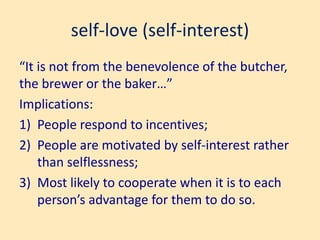

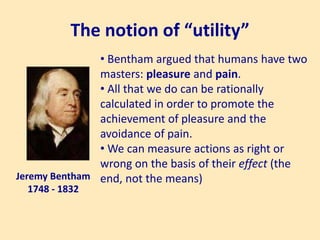

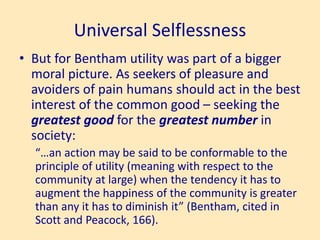

- Key assumptions in mainstream economics around self-interest, utility, and marginal utility.

- The concept of Pareto optimality and how it relates to efficiency.

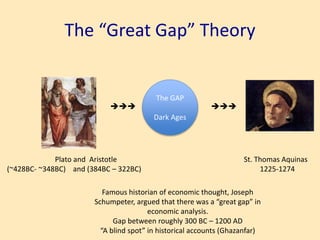

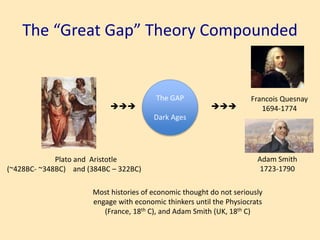

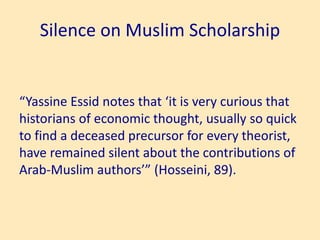

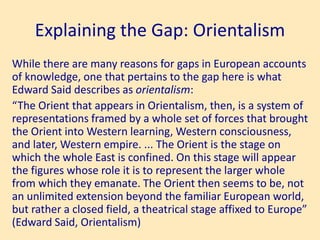

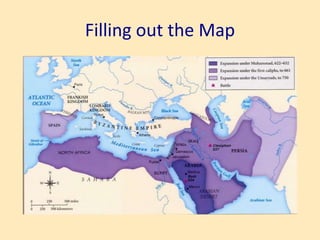

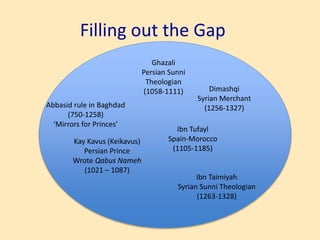

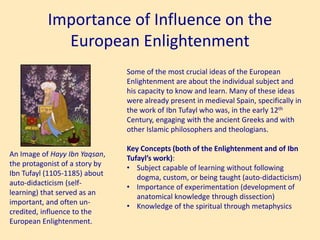

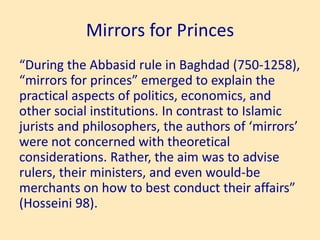

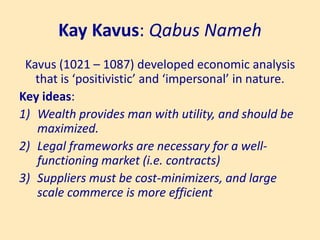

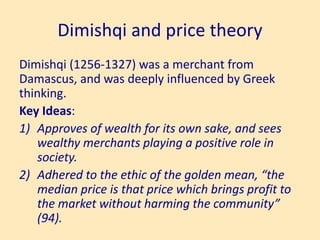

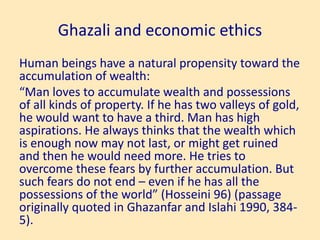

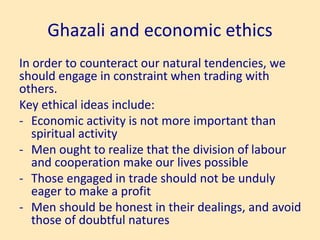

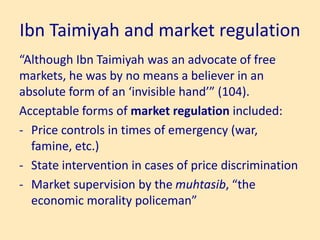

- It also discusses Islamic economic thinkers during the alleged "Great Gap" in economic thought between ancient Greece and the European Enlightenment, including their contributions to ideas around markets, ethics, and regulation. Specifically, it outlines the works and ideas of Ghazali, Dimishqi, Ibn Taimiyah, Kay Kavus, and Ibn Tuf

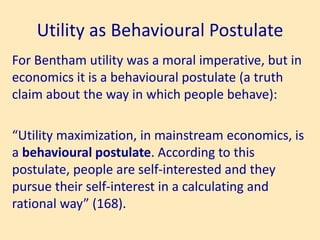

![Utility as Behavioural Postulate

“..assuming that most human beings are rational

economic beings who possess the attributes of

homo economicus makes it easier to fit them into

mathematical models. […] most mainstream

economists assume that human beings think of

their advantage and self-interest in terms of

quantity and price, and since price can be

measured, we can then start to think about

economics in mathematical terms” (167).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2-sosc2330lecture22022-230215090959-265749bb/85/L2-SOSC-2330-Lecture-2-2022-pptx-12-320.jpg)

![Robinson Crusoe

“Who is Homo Economicus? Originally he was a

fiction invented by economists. Their model was

a character from the novel Robinson Crusoe by

Daniel Defoe, imagined as a metaphor for an

Englishman discovering a virgin land (in all

senses of the term – with no inhabitants, no

past, on the American model) and leading a

‘rational’ life. […] In all circumstances Robinson

Crusoe tried to maximize is wellbeing, like a firm

that maximizes its profits” (Cohen, 15).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2-sosc2330lecture22022-230215090959-265749bb/85/L2-SOSC-2330-Lecture-2-2022-pptx-17-320.jpg)

![Pareto Optimality

Vilfredo Pareto

1848 - 1923

• Pareto optimal allocation

(or Pareto Efficiency): “we

cannot reallocate resources

to improve one person’s

welfare without impairing at

least one other person’s

welfare”

• Pareto improvement:

“where a change in resource

allocation is preferred by one

or more […] and opposed by

no one” (Rhoads, 63)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/l2-sosc2330lecture22022-230215090959-265749bb/85/L2-SOSC-2330-Lecture-2-2022-pptx-21-320.jpg)