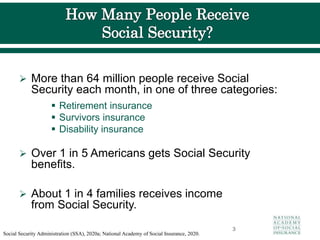

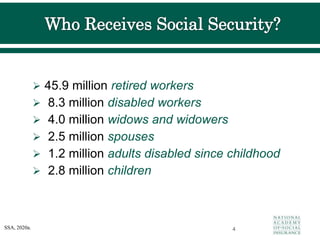

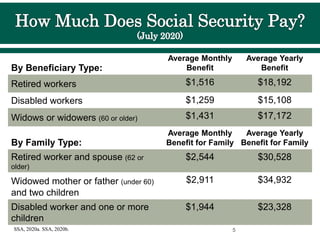

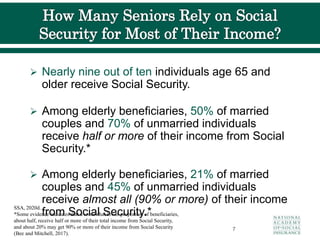

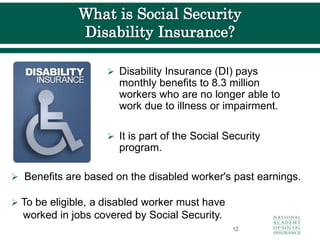

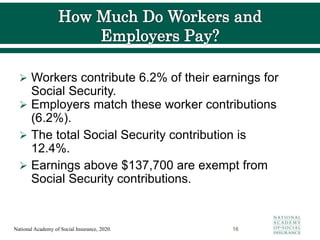

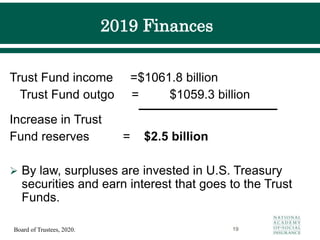

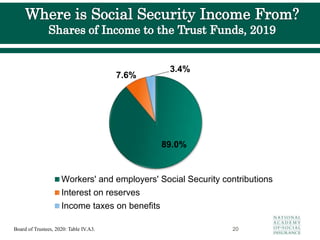

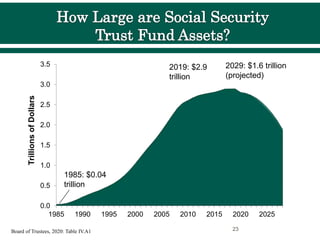

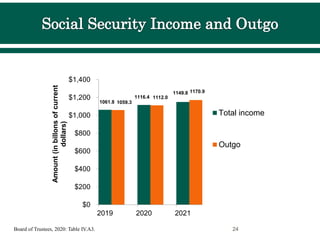

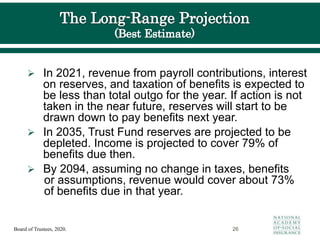

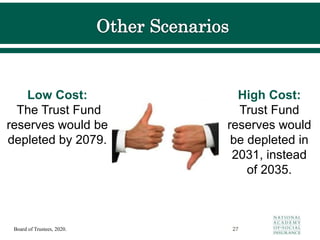

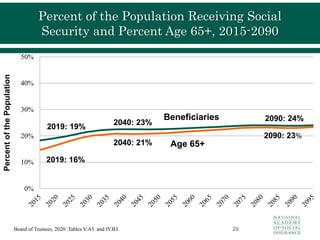

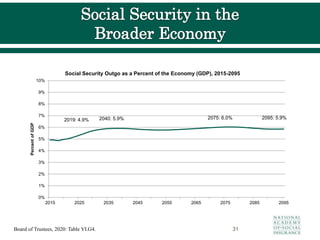

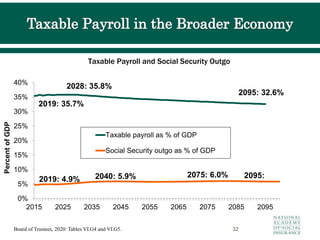

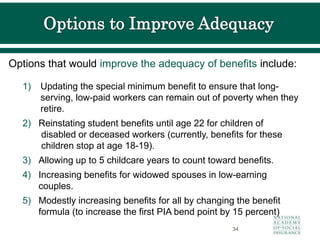

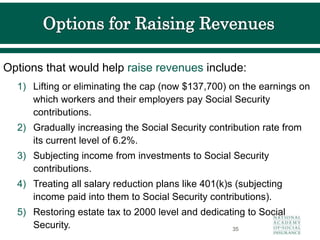

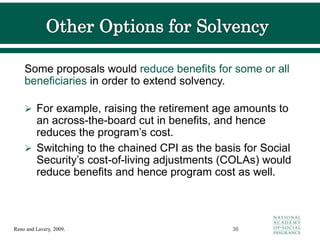

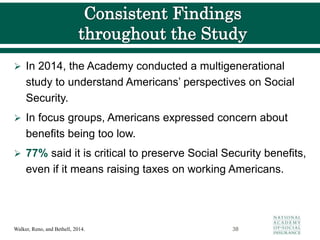

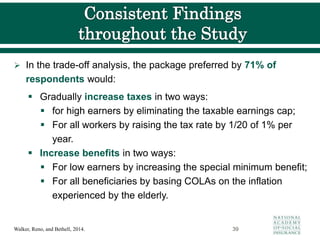

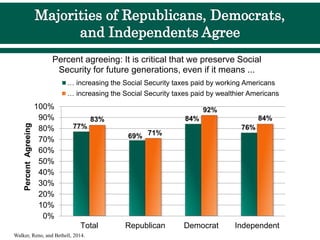

The document summarizes key facts about the U.S. Social Security program. It finds that in 2020 over 64 million people received Social Security benefits, with the average monthly benefit being $1,516 for retired workers. By 2035, the Social Security Trust Fund reserves are projected to be depleted. The document also outlines options to improve the programs financial status, such as by raising the earnings cap subject to Social Security taxes or gradually increasing contribution rates.