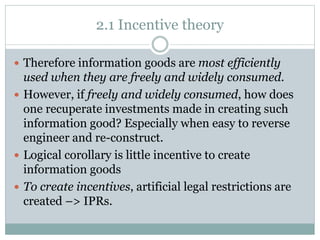

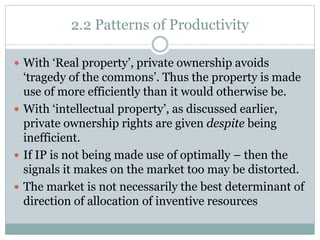

This document discusses the economics of intellectual property from three perspectives: the incentive theory, patterns of productivity theory, and issues around duplicative research efforts. The incentive theory aims to balance incentives for innovation with the inefficiencies created by intellectual property restrictions. The patterns of productivity theory examines how intellectual property affects market signals guiding resource allocation for innovation. Addressing duplicative research efforts could help minimize the waste of innovative resources. In conclusion, the economics of intellectual property is complex and countries may need different intellectual property approaches depending on their situations and intellectual property should be considered alongside broader socioeconomic issues.