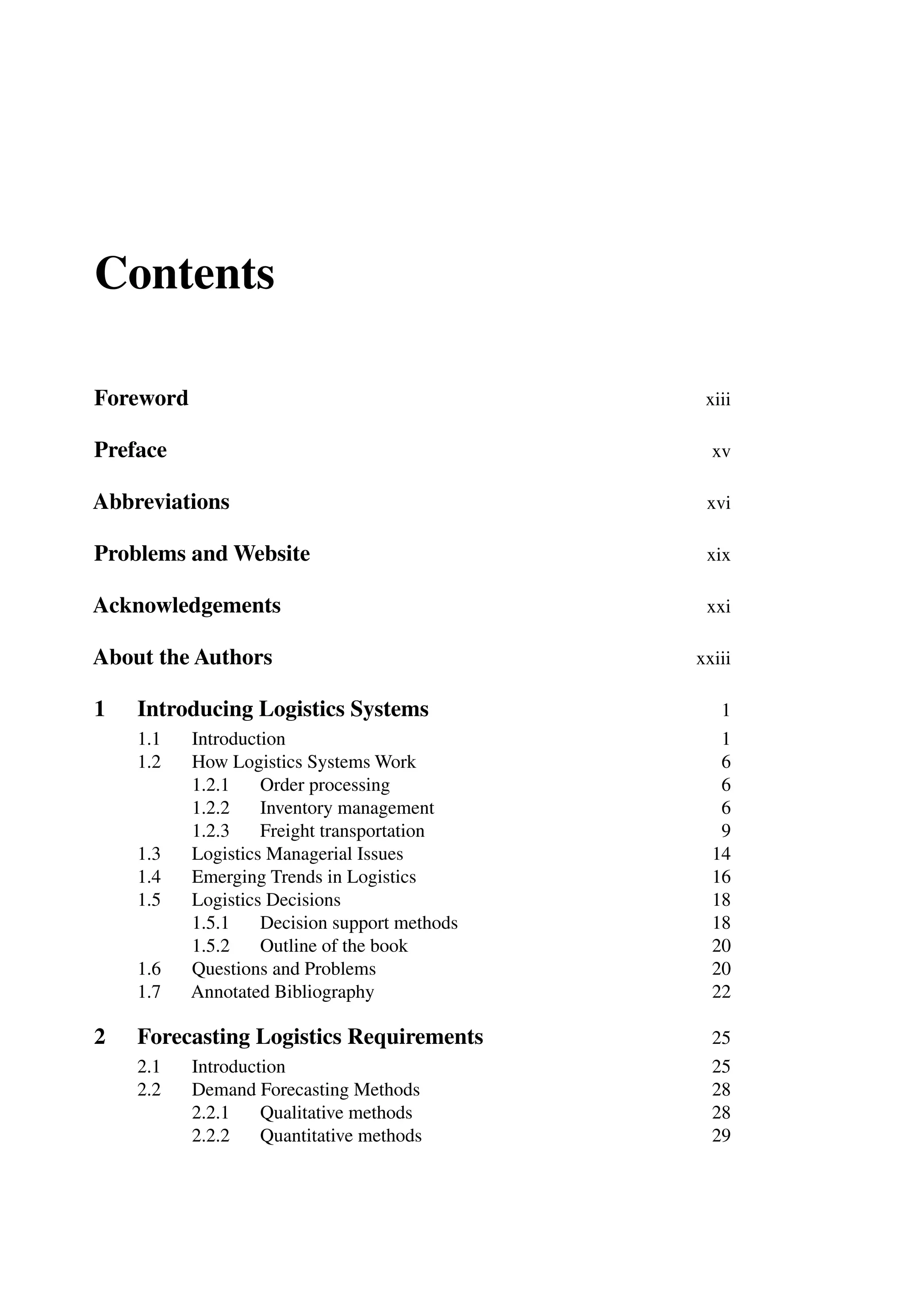

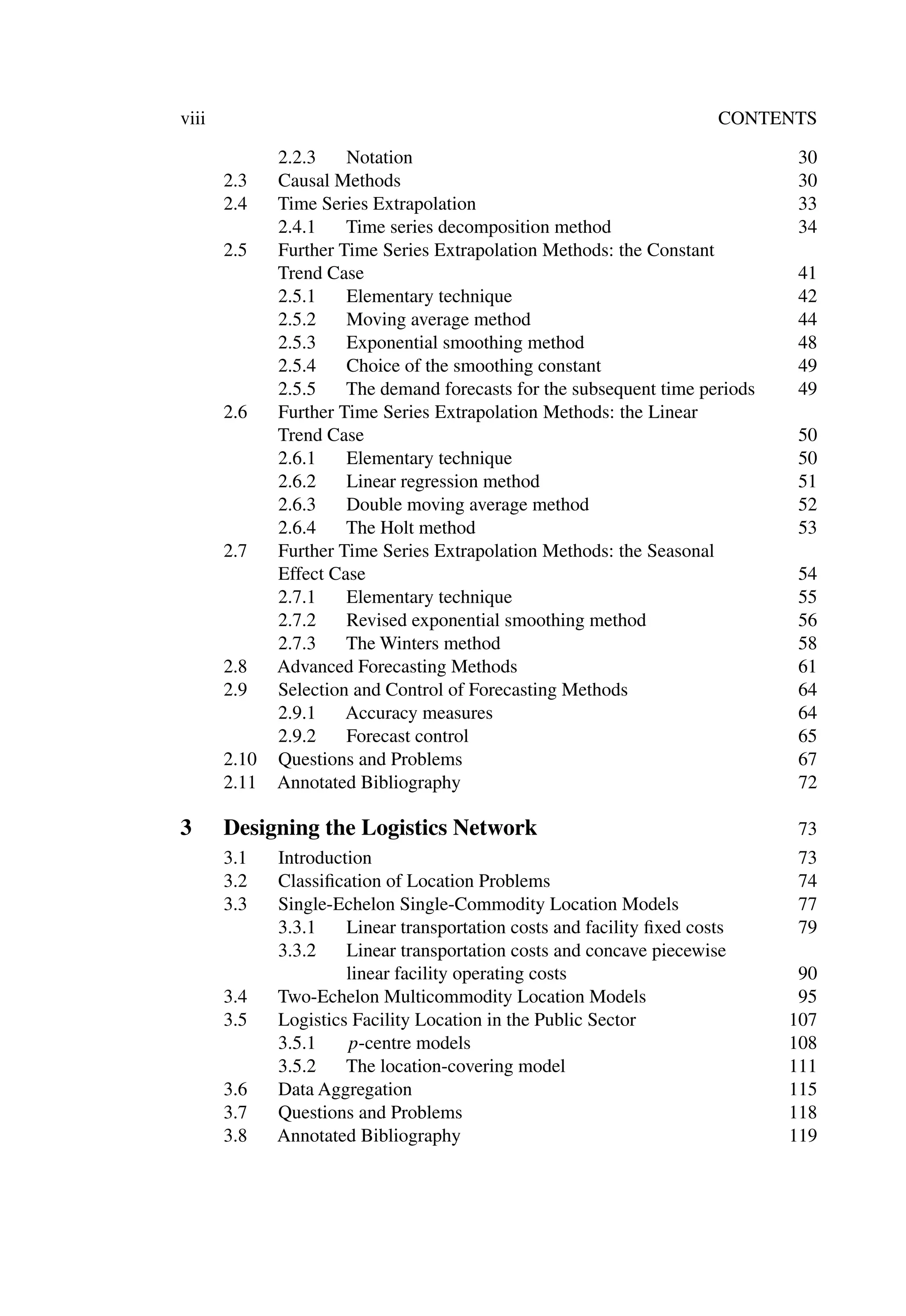

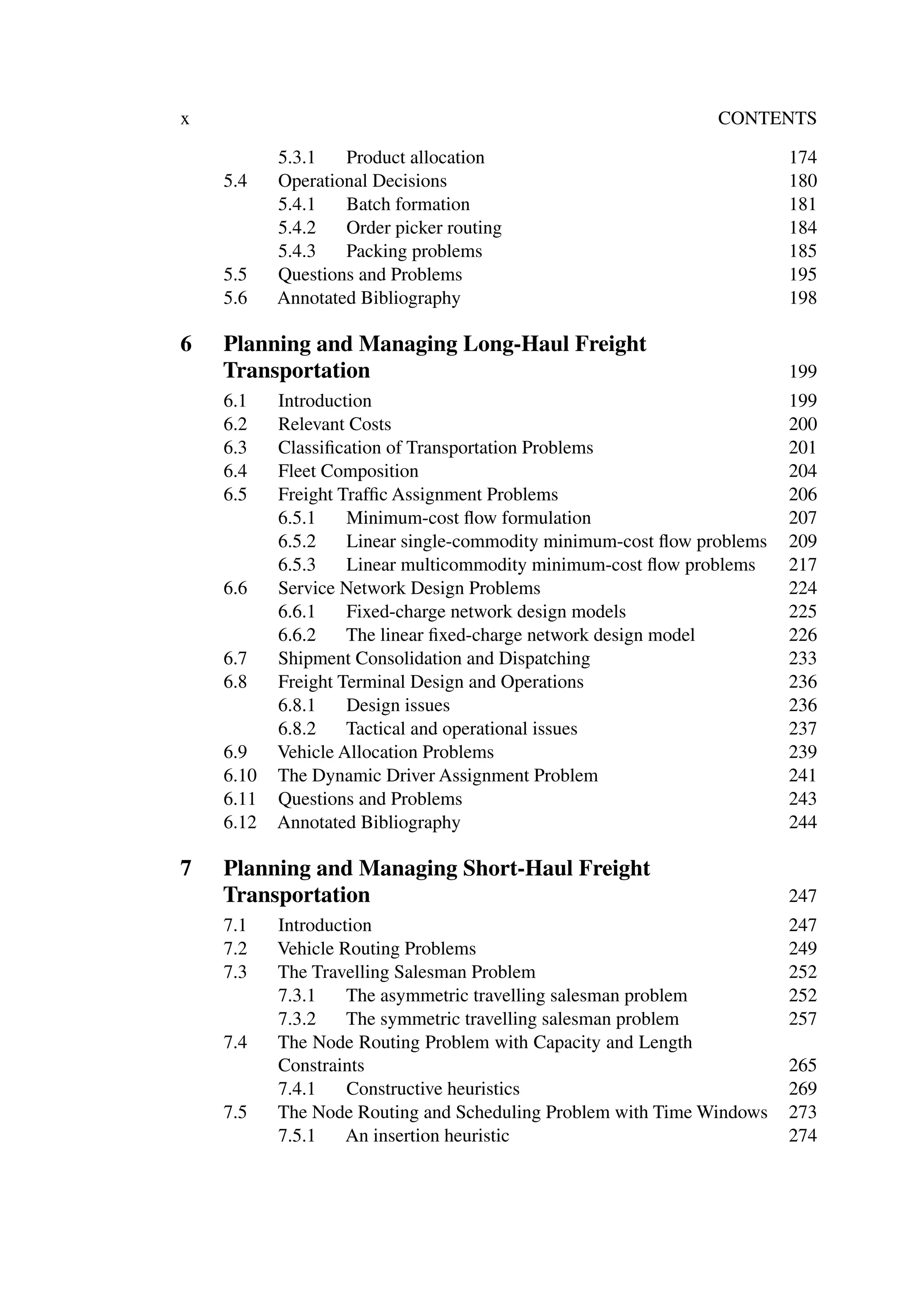

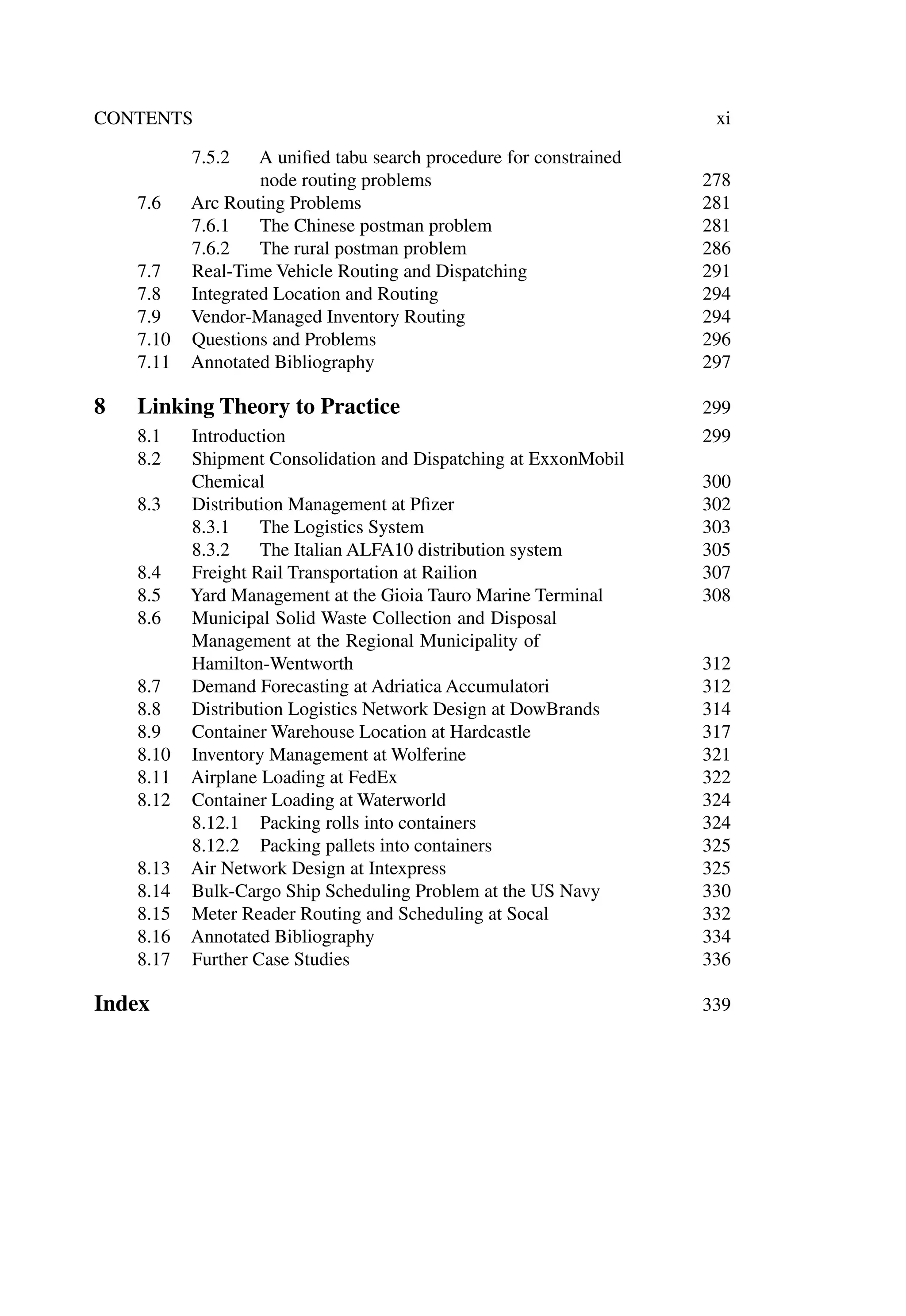

Introduction to logistics systems planning and control 1st Edition Gianpaolo Ghiani

Introduction to logistics systems planning and control 1st Edition Gianpaolo Ghiani

Introduction to logistics systems planning and control 1st Edition Gianpaolo Ghiani