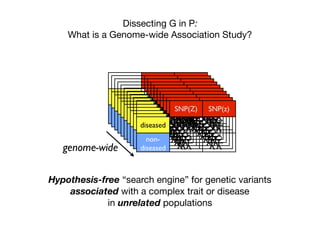

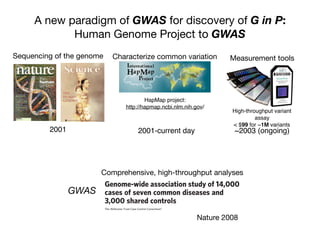

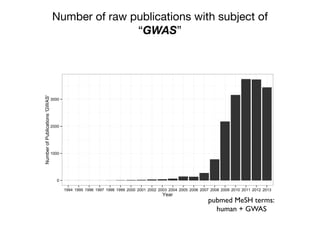

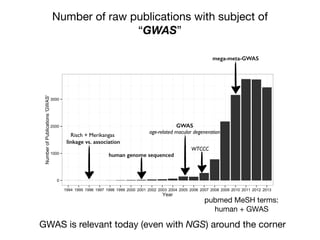

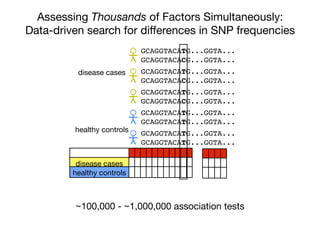

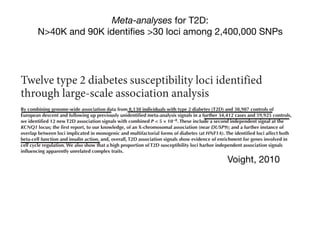

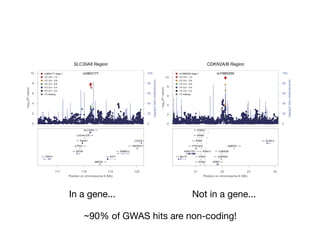

This document provides an introduction to genome-wide association studies (GWAS) and their role in discovering the genetic basis of complex traits and diseases. It explains that GWAS are a hypothesis-free approach to searching the entire human genome for genetic variants associated with a trait using common single nucleotide polymorphisms. Over 2,000 traits and diseases have been studied through GWAS, identifying over 15,000 genetic associations. The document traces the development of GWAS from early human genome sequencing and projects to characterize human genetic variation to the availability of high-throughput genotyping arrays that enabled widespread application of GWAS in disease research.

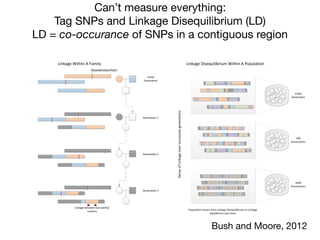

![Can’t measure everything:

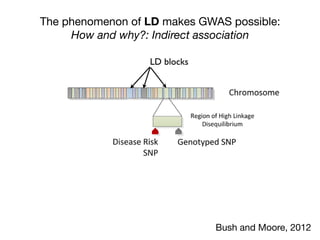

Tag SNPs and Linkage Disequilibrium

Tag SNPs are common proxies for other SNPs

500K - 1M per chip

tified significant associations for seven SNPs representing four new

T2DM loci (Table 1). In all cases, the strongest association for the

MAX statistic (see Methods) was obtained with the additive model.

of this gene (Fig. 2a)

solely in the secretory

final stages of insulin

*

*

*

0

2

4

–log10[P]

–log10[P]

*

4954642sr

2373971sr

3373971sr

445409sr

8012261sr

3349941sr

883429sr

2019462sr

0349941sr

90350501sr

036169sr

0415007sr

2225991sr

6136642sr

8136642sr

1869646sr

8798751sr

04928201sr

3926642sr

5926642sr

43666231sr

9926642sr

2954642sr

01350501sr

5769646sr

4577187sr

4769646sr

41350501sr

5784931sr

2173387sr

39250501sr

5050007sr

7492602sr

1255051sr

156868sr

4373387sr

4784931sr

7501107sr

2697402sr

91518711sr

6461001sr

29250501sr

5889103sr

8669646sr

0889103sr

4688392sr

SLC30A8 IDE

0

2

4

7912381sr

3148707sr

0283856sr

52078111sr

5227373sr

0491242sr

2369412sr

2297881sr

662155sr

7790197sr

44068701sr

35075221sr

5826807sr

7851092sr

9409522sr

–log10[P]

–log10[P]

EXT2 ALX4

0

2

4

*** *

0

2

4

a b

c d

LD block

2 alleles are correlated because they are inherited

together

Sladek et al, 2007](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-16-320.jpg)

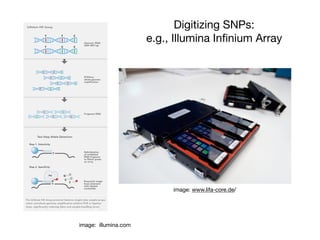

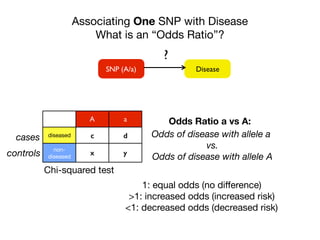

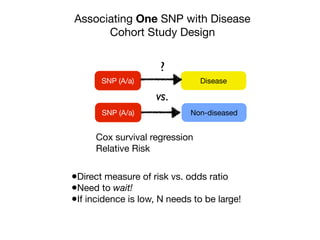

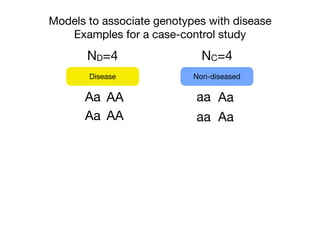

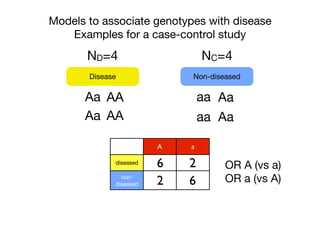

![Associating One SNP with Disease

Calculating the Odds Ratio

DiseaseSNP (A/a)

?

A a

diseased c d

non-

diseased

x y

cases

controls

Chi-squared test

Odds Ratio

dx

cy

y/x

d/c

[d/(d+y)]/[y/(d+y)]

Odds Ratio a vs A:

[c/(x+y)]/[x/(c+x)]

Odds with allele a

Odds with allele A

How would you interpret an OR of 2?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-21-320.jpg)

![Human Hap300 chip, showing no T2DM association in stage 1

(P . 0.01) and separated by at least 100 kb. Using the first principal

component as a covariate for ancestry differences between cases and

controls, we tested for association between rs932206 and disease

status. Our result suggests that this apparent association is largely

BMI on the association between marker and disease, as it is asymp-

totically equivalent to the Armitage trend test used to detect asso-

ciation in stages 1 and 2. None of the associations (Supplementary

Table 7) was substantially changed by considering the effects of these

covariates.

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

15

10

5

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

1 2 3 4 5

6 7 8 9 10

11 12 13 14 15

16 17 19 20

21 22 X

18

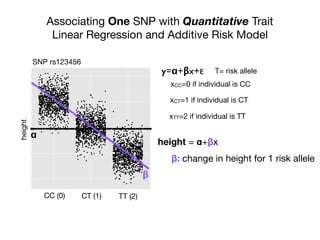

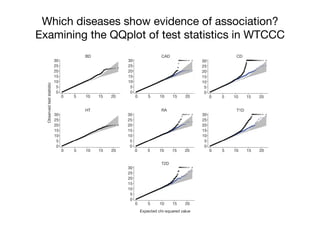

Figure 1 | Graphical summary of stage 1 association results. T2DM

association was determined for SNPs on the Human1 and Hap300 chips. The

x axis represents the chromosome position from pter; the y axis shows

2log10[pMAX], the P-value obtained by the MAX statistic, for each SNP

(Note the different scale on the y axis of the chromosome 10 plot.). SNPs that

passed the cutoff for a fast-tracked second stage are highlighted in red.

882

Nature©2007 Publishing Group Sladek, 2007](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-44-320.jpg)

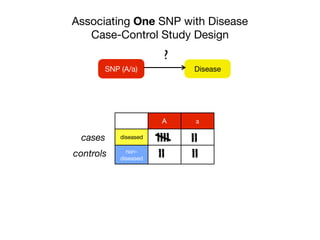

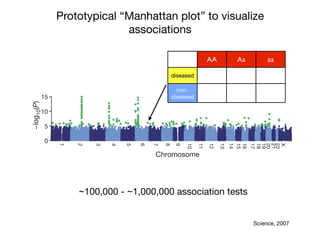

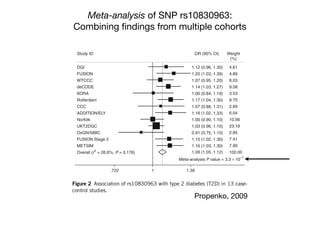

![Identification of four novel T2DM loci

Our fast-track stage 2 genotyping confirmed the reported association

for rs7903146 (TCF7L2) on chromosome 10, and in addition iden-

tified significant associations for seven SNPs representing four new

T2DM loci (Table 1). In all cases, the strongest association for the

MAX statistic (see Methods) was obtained with the additive model.

The most significant of these corresponds to rs13266634, a non-

synonymous SNP (R325W) in SLC30A8, located in a 33-kb linkage

disequilibrium block on chromosome 8, containing only the 39 end

of this gene (Fig. 2a). SLC30A8 encodes a zinc transporter expressed

solely in the secretory vesicles of b-cells and is thus implicated in the

final stages of insulin biosynthesis, which involve co-crystallization

Table 1 | Confirmed association results

SNP Chromosome Position

(nucleotides)

Risk

allele

Major

allele

MAF

(case)

MAF

(ctrl)

Odds ratio

(het)

Odds ratio

(hom)

PAR ls Stage 2

pMAX

Stage 2 pMAX

(perm)

Stage 1

pMAX

Stage 1 pMAX

(perm)

Nearest

gene

rs7903146 10 114,748,339 T C 0.406 0.293 1.65 6 0.19 2.77 6 0.50 0.28 1.0546 1.5 3 10234

,1.0 3 1027

3.2 3 10217

,3.3 3 10210

TCF7L2

rs13266634 8 118,253,964 C C 0.254 0.301 1.18 6 0.25 1.53 6 0.31 0.24 1.0089 6.1 3 1028

5.0 3 1027

2.1 3 1025

1.8 3 1025

SLC30A8

rs1111875 10 94,452,862 G G 0.358 0.402 1.19 6 0.19 1.44 6 0.24 0.19 1.0069 3.0 3 1026

7.4 3 1026

9.1 3 1026

7.3 3 1026

HHEX

rs7923837 10 94,471,897 G G 0.335 0.377 1.22 6 0.21 1.45 6 0.25 0.20 1.0065 7.5 3 1026

2.2 3 1025

3.4 3 1026

2.5 3 1026

HHEX

rs7480010 11 42,203,294 G A 0.336 0.301 1.14 6 0.13 1.40 6 0.25 0.08 1.0041 1.1 3 1024

2.9 3 1024

1.5 3 1025

1.2 3 1025

LOC387761

rs3740878 11 44,214,378 A A 0.240 0.272 1.26 6 0.29 1.46 6 0.33 0.24 1.0046 1.2 3 1024

2.8 3 1024

1.8 3 1025

1.3 3 1025

EXT2

rs11037909 11 44,212,190 T T 0.240 0.271 1.27 6 0.30 1.47 6 0.33 0.25 1.0045 1.8 3 1024

4.5 3 1024

1.8 3 1025

1.3 3 1025

EXT2

rs1113132 11 44,209,979 C C 0.237 0.267 1.15 6 0.27 1.36 6 0.31 0.19 1.0044 3.3 3 1024

8.1 3 1024

3.7 3 1025

2.9 3 1025

EXT2

Significant T2DM associations were confirmed for eight SNPs in five loci. Allele frequencies, odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) and PAR were calculated using only the stage 2 data. Allele

frequencies in the controls were very close to those reported for the CEU set (European subjects genotyped in the HapMap project). Induced sibling recurrent risk ratios (ls) were estimated using

stage 2 genotype counts for the control subjects and assuming a T2DM prevalence of 7% in the French population. hom, homozygous; het, heterozygous; major allele, the allele with the higher

frequency in controls; pMAX, P-value of the MAX statistic from the x2

distribution; pMAX (perm), P-value of the MAX statistic from the permutation-derived empirical distribution (pMAX and

pMAX (perm) are adjusted for variance inflation); risk allele, the allele with higher frequency in cases compared with controls.

0

2

4

–log10[P]

–log10[P]

SLC30A8 IDE HHEXKIF11

0

2

4

a b

NATURE|Vol 445|22 February 2007 ARTICLES

Sladek, 2007

5

3

1

5

3

1

15

10

5

1 1 1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

5

3

1

3 4 5

8 9 10

13 14 15

19 20

X

18

DM 2log10[pMAX], the P-value obtained by the MAX statistic, for each SNP

How would you interpret the p-

values?

Odds ratios?

Confirmed 8 SNPs with N ~ 1000](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-45-320.jpg)

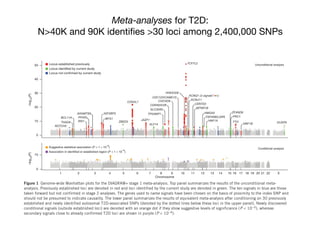

![pporting!Figures!

!

!

~90% of GWAS hits are non-coding!

Stamatoyannopoulos, Science 2012

Systematic Localization of Common

Disease-Associated Variation in

Regulatory DNA

Matthew T. Maurano,1

* Richard Humbert,1

* Eric Rynes,1

* Robert E. Thurman,1

Eric Haugen,1

Hao Wang,1

Alex P. Reynolds,1

Richard Sandstrom,1

Hongzhu Qu,1,2

Jennifer Brody,3

Anthony Shafer,1

Fidencio Neri,1

Kristen Lee,1

Tanya Kutyavin,1

Sandra Stehling-Sun,1

Audra K. Johnson,1

Theresa K. Canfield,1

Erika Giste,1

Morgan Diegel,1

Daniel Bates,1

R. Scott Hansen,4

Shane Neph,1

Peter J. Sabo,1

Shelly Heimfeld,5

Antony Raubitschek,6

Steven Ziegler,6

Chris Cotsapas,7,8

Nona Sotoodehnia,3,9

Ian Glass,10

Shamil R. Sunyaev,11

Rajinder Kaul,4

John A. Stamatoyannopoulos1,12

†

Genome-wide association studies have identified many noncoding variants associated with common

diseases and traits. We show that these variants are concentrated in regulatory DNA marked by

deoxyribonuclease I (DNase I) hypersensitive sites (DHSs). Eighty-eight percent of such DHSs are active

during fetal development and are enriched in variants associated with gestational exposure–related

phenotypes. We identified distant gene targets for hundreds of variant-containing DHSs that may explain

phenotype associations. Disease-associated variants systematically perturb transcription factor recognition

sequences, frequently alter allelic chromatin states, and form regulatory networks. We also demonstrated

tissue-selective enrichment of more weakly disease-associated variants within DHSs and the de novo

identification of pathogenic cell types for Crohn’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and an electrocardiogram

trait, without prior knowledge of physiological mechanisms. Our results suggest pervasive involvement of

regulatory DNA variation in common human disease and provide pathogenic insights into diverse disorders.

D

isease- and trait-associated genetic variants

are rapidly being identified with genome-

wide association studies (GWAS) and re-

lated strategies (1). To date, hundreds of GWAS

have been conducted, spanning diverse diseases

and quantitative phenotypes (2) (fig. S1A). How-

ever, the majority (~93%) of disease- and trait-

associated variants emerging from these studies

lie within noncoding sequence (fig. S1B), com-

plicating their functional evaluation. Several lines

of evidence suggest the involvement of a propor-

tion of such variants in transcriptional regulatory

mechanisms, including modulation of promoter

and enhancer elements (3–6) and enrichment with-

in expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) (3, 7, 8).

Human regulatory DNA encompasses a vari-

ety of cis-regulatory elements within which the co-

operative binding of transcription factors creates

focal alterations in chromatin structure. Deoxy-

ribonuclease I (DNase I) hypersensitive sites (DHSs)

are sensitive and precise markers of this actuated

regulatory DNA, and DNase I mapping has been

instrumental in the discovery and census of hu-

man cis-regulatory elements (9). We performed

DNase I mapping genome-wide (10) in 349 cell

and tissue samples, including 85 cell types studied

under the ENCODE Project (10) and 264 sam-

ples studied under the Roadmap Epigenomics

Program (11). These encompass several classes

nome. In total, we identified 3,899,693 distinct

DHS positions along the genome (collectively

spanning 42.2%), each of which was detected in

one or more cell or tissue types (median = 5).

Disease- and trait-associated variants are

concentrated in regulatory DNA. We examined

the distribution of 5654 noncoding genome-wide

significant associations [5134 unique single-

nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs); fig. S1 and

table S2] for 207 diseases and 447 quantitative

traits (2) with the deep genome-scale maps of

regulatory DNA marked by DHSs. This revealed

a collective 40% enrichment of GWAS SNPs in

DHSs (fig. S1C, P < 10−55

, binomial, compared to

the distribution of HapMap SNPs). Fully 76.6%

of all noncoding GWAS SNPs either lie within a

DHS (57.1%, 2931 SNPs) or are in complete

linkage disequilibrium (LD) with SNPs in a near-

by DHS (19.5%, 999 SNPs) (Fig. 1A) (12). To con-

firm this enrichment, we sampled variants from

the 1000 Genomes Project (13) with the same ge-

nomic feature localization (intronic versus inter-

genic), distance from the nearest transcriptional

start site, and allele frequency in individuals of

European ancestry. We confirmed significant en-

richment both for SNPs within DHSs (P < 10−59

,

simulation) and also including variants in com-

plete LD (r 2

= 1) with SNPs in DHSs (P < 10−37

,

simulation) (fig. S2).

In total, 47.5% of GWAS SNPs fall within

gene bodies (fig. S1B); however, only 10.9% of

intronic GWAS SNPs within DHSs are in strong

LD (r2

≥ 0.8) with a coding SNP, indicating that

the vast majority of noncoding genic variants

are not simply tagging coding sequence. Analo-

gously, only 16.3% of GWAS variants within

coding sequences are in strong LD with variants in

DHSs. SNPs on widely used genotyping arrays

(e.g., Affymetrix) were modestly enriched with-

in DHSs (fig. S2), possibly due to selection of

SNPs with robust experimental performance in

genotyping assays. However, we found no evi-

dence for sequence composition bias (table S3).

To further examine the enrichment of GWAS

SNPs in regulatory DNA, we systematically clas-

sified all noncoding GWAS SNPs by the quality

1

Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington,

Seattle, WA 98195, USA. 2

Laboratory of Disease Genomics

RESEARCH ARTICLE

onSeptember12,2012www.sciencemag.orgDownloadedfrom](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-51-320.jpg)

![Common claims discussed in regards to GWAS:

Despite issues, yielded many discoveries vs. cost

to a doubling of the number of associated variants discov-

ered. The proportion of genetic variation explained by

significantly associated SNPs is usually low (typically less

than 10%) for many complex traits, but for diseases such

as CD and multiple sclerosis (MS [MIM 126200]), and for

quantitative traits such as height and lipid traits, between

Figure 1. GWAS Discoveries over Time

Data obtained from the Published GWAS Catalog (see Web

Resources). Only the top SNPs representing loci with association

p values < 5 3 10À8

are included, and so that multiple counting

is avoided, SNPs identified for the same traits with LD r2

> 0.8 esti-

mated from the entire HapMap samples are excluded.

~500,000 SNP chips x ~$500/chip

= $250M

Five years of GWAS Discovery (Visscher, 2012)

$250M / ~2000 loci

= $125K/locus

Candidate genes: >$250M!

100 NIH R01s

Fighter jet

Hadron Collider: $9B](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-53-320.jpg)

![evol

part

ease

tase

well

biol

T

capt

imp

STR

reve

subs

libri

−log10(P)

0

5

10

15

Chromosome

22

X

21

20

19

18

17

16

15

14

13

12

11

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

80

60

100

teststatistic

a

b

NATURE|Vol 447|7 June 2007

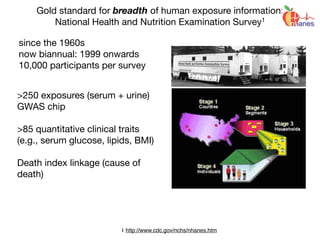

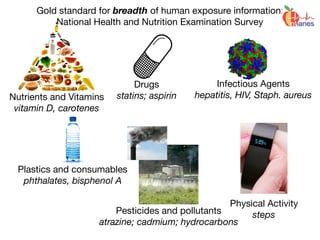

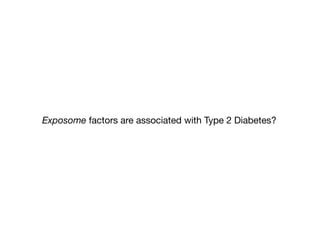

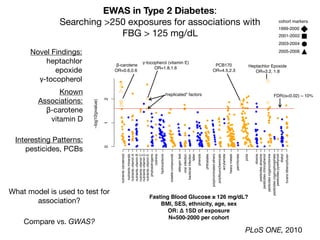

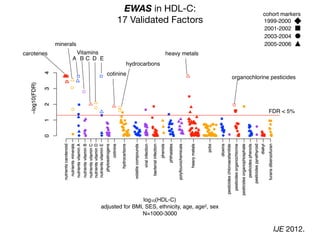

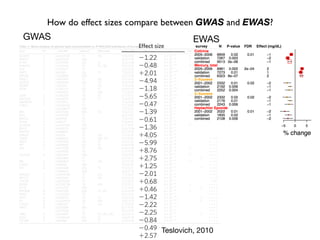

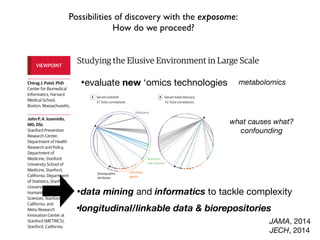

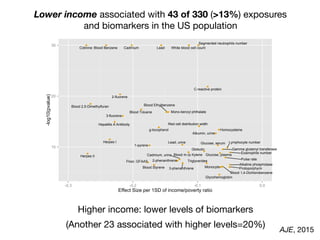

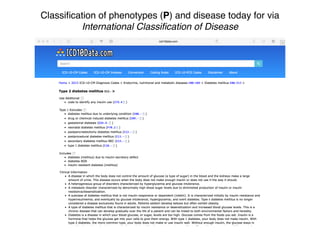

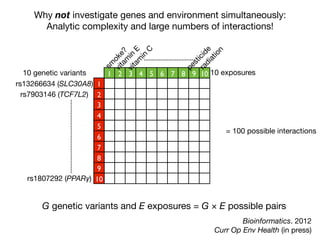

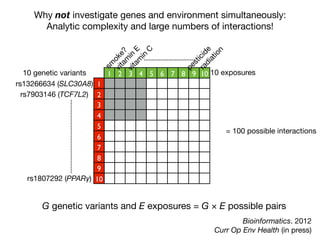

Environment-Wide Association Studies (EWAS):

A GWAS-like study for the environment

What specific environmental “loci” are associated to disease?

Environmental Category

Vitam

ins

β-carotene

M

etals

lead

O

rganophosphate

Pesticides

H

ydrocarbons

2-hydroxyfluorene [factor]

case

control](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-69-320.jpg)

![Longitudinal Study:

“Gold Standard” for Validation

•exposure changing through time

•reverse causality bias

•compute disease risk

time

Disease

?

Exposure

DiseaseRisk

[low]

[high]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-93-320.jpg)

![Adjusted Hazard Ratio

-log10(pvalue)

0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 2.0 2.4 2.8

02468

1

2

3

4

5

67

1 Physical Activity

2 Does anyone smoke in home?

3 Cadmium

4 Cadmium, urine

5 Past smoker

6 Current smoker

7 trans-lycopene

(11) 1

2

3 4

5 6

78

9

10 1112

13 14

1516

1 age (10 year increment)

2 SES_1

3 male

4 SES_0

5 black

6 SES_2

7 SES_3

8 education_hs

9 other_eth

10 mexican

11 occupation_blue_semi

12 education_less_hs

13 occupation_never

14 occupation_blue_high

15 occupation_white_semi

16 other_hispanic

(69)

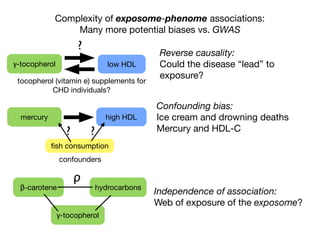

All-cause mortality:

253 exposure/behavior associations in survival

age, sex, income, education, race/ethnicity, occupation [in red]

FDR < 5%

sociodemographics

replicated factor

IJE, 2013](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-95-320.jpg)

![Adjusted Hazard Ratio

-log10(pvalue)

0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 1.2 1.4 1.6 2.0 2.4 2.8

02468

1

2

3

4

5

67

1 Physical Activity

2 Does anyone smoke in home?

3 Cadmium

4 Cadmium, urine

5 Past smoker

6 Current smoker

7 trans-lycopene

(11) 1

2

3 4

5 6

78

9

10 1112

13 14

1516

1 age (10 year increment)

2 SES_1

3 male

4 SES_0

5 black

6 SES_2

7 SES_3

8 education_hs

9 other_eth

10 mexican

11 occupation_blue_semi

12 education_less_hs

13 occupation_never

14 occupation_blue_high

15 occupation_white_semi

16 other_hispanic

(69)

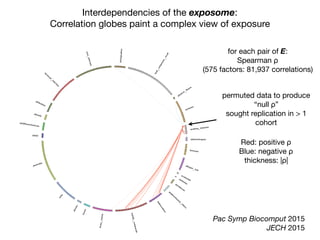

EWAS (re)-identifies factors associated with all-cause mortality:

Volcano plot of 200 associations

age (10 years)

income (quintile 2)

income (quintile 1)

male

black income (quintile 3)

any one smoke in home?

age, sex, income, education, race/ethnicity, occupation [in red]

serum and urine cadmium

[1 SD]

past smoker?

current smoker?serum lycopene

[1SD]

physical activity

[low, moderate, high activity]*

*derived from METs per activity and categorized by Health.gov guidelines

R2 ~ 2%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-96-320.jpg)

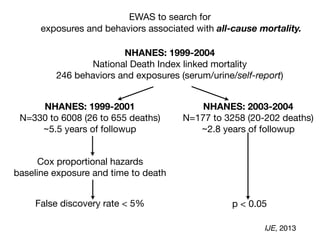

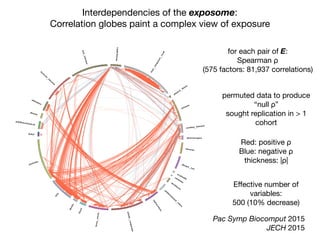

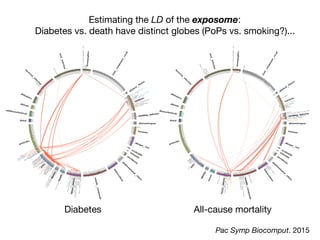

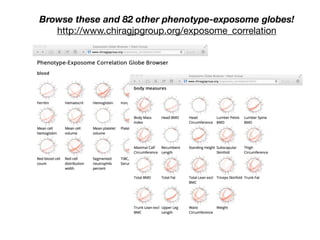

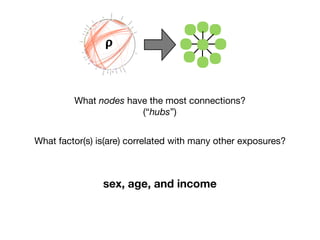

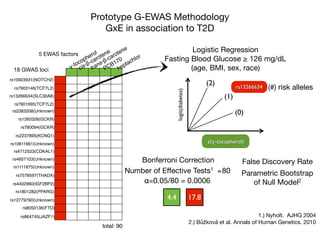

![Correlation Structure of the Exposome?

Analogy: “Linkage Disequilibrium”

Identification of four novel T2DM loci

Our fast-track stage 2 genotyping confirmed the reported association

for rs7903146 (TCF7L2) on chromosome 10, and in addition iden-

tified significant associations for seven SNPs representing four new

T2DM loci (Table 1). In all cases, the strongest association for the

MAX statistic (see Methods) was obtained with the additive model.

The most significant of these corresponds to rs13266634, a non-

synonymous SNP (R325W) in SLC30A8, located in a 33-kb linkage

disequilibrium block on chromosome 8, containing only the 39 end

of this gene (Fig. 2a). SLC30A8 encodes a zinc transporter expressed

solely in the secretory vesicles of b-cells and is thus implicated in the

final stages of insulin biosynthesis, which involve co-crystallization

Table 1 | Confirmed association results

SNP Chromosome Position

(nucleotides)

Risk

allele

Major

allele

MAF

(case)

MAF

(ctrl)

Odds ratio

(het)

Odds ratio

(hom)

PAR ls Stage 2

pMAX

Stage 2 pMAX

(perm)

Stage 1

pMAX

Stage 1 pMAX

(perm)

Nearest

gene

rs7903146 10 114,748,339 T C 0.406 0.293 1.65 6 0.19 2.77 6 0.50 0.28 1.0546 1.5 3 10234

,1.0 3 1027

3.2 3 10217

,3.3 3 10210

TCF7L2

rs13266634 8 118,253,964 C C 0.254 0.301 1.18 6 0.25 1.53 6 0.31 0.24 1.0089 6.1 3 1028

5.0 3 1027

2.1 3 1025

1.8 3 1025

SLC30A8

rs1111875 10 94,452,862 G G 0.358 0.402 1.19 6 0.19 1.44 6 0.24 0.19 1.0069 3.0 3 1026

7.4 3 1026

9.1 3 1026

7.3 3 1026

HHEX

rs7923837 10 94,471,897 G G 0.335 0.377 1.22 6 0.21 1.45 6 0.25 0.20 1.0065 7.5 3 1026

2.2 3 1025

3.4 3 1026

2.5 3 1026

HHEX

rs7480010 11 42,203,294 G A 0.336 0.301 1.14 6 0.13 1.40 6 0.25 0.08 1.0041 1.1 3 1024

2.9 3 1024

1.5 3 1025

1.2 3 1025

LOC387761

rs3740878 11 44,214,378 A A 0.240 0.272 1.26 6 0.29 1.46 6 0.33 0.24 1.0046 1.2 3 1024

2.8 3 1024

1.8 3 1025

1.3 3 1025

EXT2

rs11037909 11 44,212,190 T T 0.240 0.271 1.27 6 0.30 1.47 6 0.33 0.25 1.0045 1.8 3 1024

4.5 3 1024

1.8 3 1025

1.3 3 1025

EXT2

rs1113132 11 44,209,979 C C 0.237 0.267 1.15 6 0.27 1.36 6 0.31 0.19 1.0044 3.3 3 1024

8.1 3 1024

3.7 3 1025

2.9 3 1025

EXT2

Significant T2DM associations were confirmed for eight SNPs in five loci. Allele frequencies, odds ratios (with 95% confidence intervals) and PAR were calculated using only the stage 2 data. Allele

frequencies in the controls were very close to those reported for the CEU set (European subjects genotyped in the HapMap project). Induced sibling recurrent risk ratios (ls) were estimated using

stage 2 genotype counts for the control subjects and assuming a T2DM prevalence of 7% in the French population. hom, homozygous; het, heterozygous; major allele, the allele with the higher

frequency in controls; pMAX, P-value of the MAX statistic from the x2

distribution; pMAX (perm), P-value of the MAX statistic from the permutation-derived empirical distribution (pMAX and

pMAX (perm) are adjusted for variance inflation); risk allele, the allele with higher frequency in cases compared with controls.

*

*

*

0

2

4

–log10[P]

–log10[P]*

4954642sr

2373971sr

3373971sr

445409sr

8012261sr

3349941sr

883429sr

2019462sr

0349941sr

90350501sr

036169sr

0415007sr

2225991sr

6136642sr

8136642sr

1869646sr

8798751sr

04928201sr

3926642sr

5926642sr

43666231sr

9926642sr

2954642sr

01350501sr

5769646sr

4577187sr

4769646sr

41350501sr

5784931sr

2173387sr

39250501sr

5050007sr

7492602sr

1255051sr

156868sr

4373387sr

4784931sr

7501107sr

2697402sr

91518711sr

6461001sr

29250501sr

5889103sr

8669646sr

0889103sr

4688392sr

SLC30A8 IDE HHEXKIF11

**

**

**

0

2

4

* *

5470942sr

7602242sr

28178111sr

1570942sr

2394424sr

8838141sr

76029511sr

37178111sr

2945391sr

2608842sr

64690501sr

1537942sr

2950249sr

0339351sr

1708842sr

195749sr

4037942sr

1137942sr

7383297sr

5781111sr

9275722sr

9537197sr

6342097sr

0383856sr

0990707sr

4184197sr

19028801sr

9125722sr

88028801sr

1974064sr

5374283sr

53465221sr

6283856sr

5058573sr

3679991sr

1118097sr

3491242sr

46078111sr

06078111sr

7912381sr

3148707sr

0283856sr

52078111sr

5227373sr

0491242sr

2369412sr

2297881sr

662155sr

7790197sr

44068701sr

35075221sr

5826807sr

7851092sr

9409522sr

–log10[P]

–log10[P]

EXT2 ALX4

0

2

4

*** * **

0

2

4

LOC387761

a b

c d

NATURE|Vol 445|22 February 2007 ARTICLES

Sladek et al., Nature Genetics (2007)

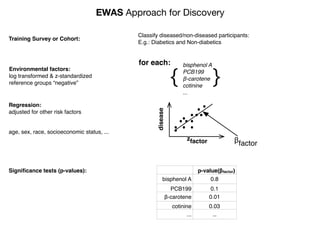

Correlation between

occurrence of genetic loci

In GWAS, allows one to trace

to the “causal” locus.

Independence of association:

How to untangle “web” of

exposure?

β-carotene hydrocarbons

γ-tocopherol

ρ](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-97-320.jpg)

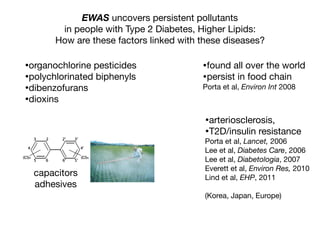

![Committee on A Framework for Developing a

New Taxonomy of Disease

Board on Life Sciences

Division on Earth and Life Studies

NRC, National Academy of Sciences 2011

The use of multiple molecular parameters to

characterize disease [P] may lead to a more

accurate and find-grained classification of

disease [P]…

“multiple molecular parameters” must include E!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-106-320.jpg)

![Alpha-carotene

Alcohol

VitaminEasalpha-tocopherol

Beta-carotene

Caffeine

Calcium

Carbohydrate

Cholesterol

Copper

Beta-cryptoxanthin

Folicacid

Folate,DFE

Foodfolate

Dietaryfiber

Iron

Energy

Lycopene

Lutein+zeaxanthin

MFA16:1

MFA18:1

MFA20:1

Magnesium

Totalmonounsaturatedfattyacids

Moisture

Niacin

PFA18:2

PFA18:3

PFA20:4

PFA22:5

PFA22:6

Totalpolyunsaturatedfattyacids

Phosphorus

Potassium

Protein

Retinol

SFA4:0

SFA6:0

SFA8:0

SFA10:0

SFA12:0

SFA14:0

SFA16:0

SFA18:0

Selenium

Totalsaturatedfattyacids

Totalsugars

Totalfat

Theobromine

VitaminA,RAE

Thiamin

VitaminB12

Riboflavin

VitaminB6

VitaminC

VitaminK

Zinc

NoSalt

OrdinarySalt

a-Carotene

VitaminB12,serum

trans-b-carotene

cis-b-carotene

b-cryptoxanthin

Folate,serum

g-tocopherol

Iron,FrozenSerum

CombinedLutein/zeaxanthin

trans-lycopene

Folate,RBC

Retinylpalmitate

Retinylstearate

Retinol

VitaminD

a-Tocopherol

Daidzein

o-Desmethylangolensin

Equol

Enterodiol

Enterolactone

Genistein

EstimatedVO2max

PhysicalActivity

Doesanyonesmokeinhome?

Total#ofcigarettessmokedinhome

Cotinine

CurrentCigaretteSmoker?

Agelastsmokedcigarettesregularly

#cigarettessmokedperdaywhenquit

#cigarettessmokedperdaynow

#dayssmokedcigsduringpast30days

Avg#cigarettes/dayduringpast30days

Smokedatleast100cigarettesinlife

Doyounowsmokecigarettes...

numberofdayssincequit

Usedsnuffatleast20timesinlife

drink5inaday

drinkperday

days5drinksinyear

daysdrinkinyear

3-fluorene

2-fluorene

3-phenanthrene

1-phenanthrene

2-phenanthrene

1-pyrene

3-benzo[c]phenanthrene

3-benz[a]anthracene

Mono-n-butylphthalate

Mono-phthalate

Mono-cyclohexylphthalate

Mono-ethylphthalate

Mono-phthalate

Mono--hexylphthalate

Mono-isobutylphthalate

Mono-n-methylphthalate

Mono-phthalate

Mono-benzylphthalate

Cadmium

Lead

Mercury,total

Barium,urine

Cadmium,urine

Cobalt,urine

Cesium,urine

Mercury,urine

Iodine,urine

Molybdenum,urine

Lead,urine

Platinum,urine

Antimony,urine

Thallium,urine

Tungsten,urine

Uranium,urine

BloodBenzene

BloodEthylbenzene

Bloodo-Xylene

BloodStyrene

BloodTrichloroethene

BloodToluene

Bloodm-/p-Xylene

1,2,3,7,8-pncdd

1,2,3,7,8,9-hxcdd

1,2,3,4,6,7,8-hpcdd

1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9-ocdd

2,3,7,8-tcdd

Beta-hexachlorocyclohexane

Gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane

Hexachlorobenzene

HeptachlorEpoxide

Mirex

Oxychlordane

p,p-DDE

Trans-nonachlor

2,5-dichlorophenolresult

2,4,6-trichlorophenolresult

Pentachlorophenol

Dimethylphosphate

Diethylphosphate

Dimethylthiophosphate

PCB66

PCB74

PCB99

PCB105

PCB118

PCB138&158

PCB146

PCB153

PCB156

PCB157

PCB167

PCB170

PCB172

PCB177

PCB178

PCB180

PCB183

PCB187

3,3,4,4,5,5-hxcb

3,3,4,4,5-pncb

3,4,4,5-tcb

Perfluoroheptanoicacid

Perfluorohexanesulfonicacid

Perfluorononanoicacid

Perfluorooctanoicacid

Perfluorooctanesulfonicacid

Perfluorooctanesulfonamide

2,3,7,8-tcdf

1,2,3,7,8-pncdf

2,3,4,7,8-pncdf

1,2,3,4,7,8-hxcdf

1,2,3,6,7,8-hxcdf

1,2,3,7,8,9-hxcdf

2,3,4,6,7,8-hxcdf

1,2,3,4,6,7,8-hpcdf

Measles

Toxoplasma

HepatitisAAntibody

HepatitisBcoreantibody

HepatitisBSurfaceAntibody

HerpesII

Albumin, urine

Uric acid

Phosphorus

Osmolality

Sodium

Potassium

Creatinine

Chloride

Total calcium

Bicarbonate

Blood urea nitrogen

Total protein

Total bilirubin

Lactate dehydrogenase LDH

Gamma glutamyl transferase

Globulin

Alanine aminotransferase ALT

Aspartate aminotransferase AST

Alkaline phosphotase

Albumin

Methylmalonic acid

PSA. total

Prostate specific antigen ratio

TIBC, Frozen Serum

Red cell distribution width

Red blood cell count

Platelet count SI

Segmented neutrophils percent

Mean platelet volume

Mean cell volume

Mean cell hemoglobin

MCHC

Hemoglobin

Hematocrit

Ferritin

Protoporphyrin

Transferrin saturation

White blood cell count

Monocyte percent

Lymphocyte percent

Eosinophils percent

C-reactive protein

Segmented neutrophils number

Monocyte number

Lymphocyte number

Eosinophils number

Basophils number

mean systolic

mean diastolic

60 sec. pulse:

60 sec HR

Total Cholesterol

Triglycerides

Glucose, serum

Insulin

Homocysteine

Glucose, plasma

Glycohemoglobin

C-peptide: SI

LDL-cholesterol

Direct HDL-Cholesterol

Bone alkaline phosphotase

Trunk Fat

Lumber Pelvis BMD

Lumber Spine BMD

Head BMD

Trunk Lean excl BMC

Total Lean excl BMC

Total Fat

Total BMD

Weight

Waist Circumference

Triceps Skinfold

Thigh Circumference

Subscapular Skinfold

Recumbent Length

Upper Leg Length

Standing Height

Head Circumference

Maximal Calf Circumference

Body Mass Index

-0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4

Value

050100150

Color Key

and Histogram

Count

http://bit.ly.com/pemap

phenotypes

exposures

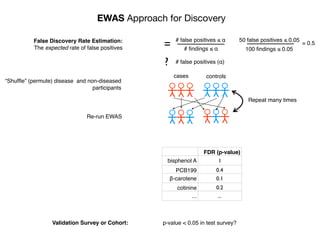

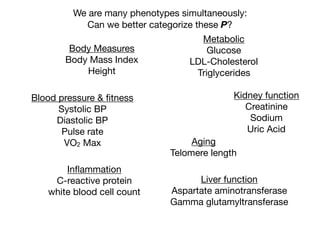

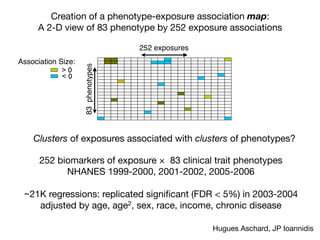

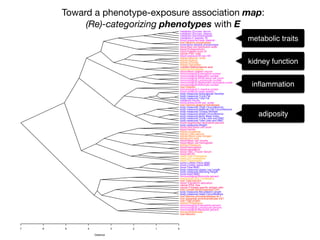

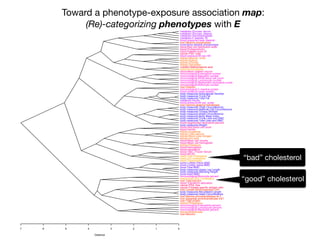

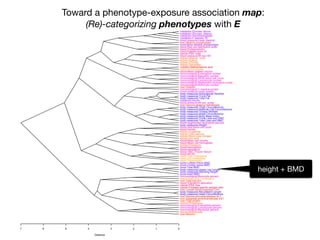

+- EWAS-derived phenotype-exposure association map:

A 2-D view of connections between P and E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-112-320.jpg)

![Alpha-carotene

Alcohol

VitaminEasalpha-tocopherol

Beta-carotene

Caffeine

Calcium

Carbohydrate

Cholesterol

Copper

Beta-cryptoxanthin

Folicacid

Folate,DFE

Foodfolate

Dietaryfiber

Iron

Energy

Lycopene

Lutein+zeaxanthin

MFA16:1

MFA18:1

MFA20:1

Magnesium

Totalmonounsaturatedfattyacids

Moisture

Niacin

PFA18:2

PFA18:3

PFA20:4

PFA22:5

PFA22:6

Totalpolyunsaturatedfattyacids

Phosphorus

Potassium

Protein

Retinol

SFA4:0

SFA6:0

SFA8:0

SFA10:0

SFA12:0

SFA14:0

SFA16:0

SFA18:0

Selenium

Totalsaturatedfattyacids

Totalsugars

Totalfat

Theobromine

VitaminA,RAE

Thiamin

VitaminB12

Riboflavin

VitaminB6

VitaminC

VitaminK

Zinc

NoSalt

OrdinarySalt

a-Carotene

VitaminB12,serum

trans-b-carotene

cis-b-carotene

b-cryptoxanthin

Folate,serum

g-tocopherol

Iron,FrozenSerum

CombinedLutein/zeaxanthin

trans-lycopene

Folate,RBC

Retinylpalmitate

Retinylstearate

Retinol

VitaminD

a-Tocopherol

Daidzein

o-Desmethylangolensin

Equol

Enterodiol

Enterolactone

Genistein

EstimatedVO2max

PhysicalActivity

Doesanyonesmokeinhome?

Total#ofcigarettessmokedinhome

Cotinine

CurrentCigaretteSmoker?

Agelastsmokedcigarettesregularly

#cigarettessmokedperdaywhenquit

#cigarettessmokedperdaynow

#dayssmokedcigsduringpast30days

Avg#cigarettes/dayduringpast30days

Smokedatleast100cigarettesinlife

Doyounowsmokecigarettes...

numberofdayssincequit

Usedsnuffatleast20timesinlife

drink5inaday

drinkperday

days5drinksinyear

daysdrinkinyear

3-fluorene

2-fluorene

3-phenanthrene

1-phenanthrene

2-phenanthrene

1-pyrene

3-benzo[c]phenanthrene

3-benz[a]anthracene

Mono-n-butylphthalate

Mono-phthalate

Mono-cyclohexylphthalate

Mono-ethylphthalate

Mono-phthalate

Mono--hexylphthalate

Mono-isobutylphthalate

Mono-n-methylphthalate

Mono-phthalate

Mono-benzylphthalate

Cadmium

Lead

Mercury,total

Barium,urine

Cadmium,urine

Cobalt,urine

Cesium,urine

Mercury,urine

Iodine,urine

Molybdenum,urine

Lead,urine

Platinum,urine

Antimony,urine

Thallium,urine

Tungsten,urine

Uranium,urine

BloodBenzene

BloodEthylbenzene

Bloodo-Xylene

BloodStyrene

BloodTrichloroethene

BloodToluene

Bloodm-/p-Xylene

1,2,3,7,8-pncdd

1,2,3,7,8,9-hxcdd

1,2,3,4,6,7,8-hpcdd

1,2,3,4,6,7,8,9-ocdd

2,3,7,8-tcdd

Beta-hexachlorocyclohexane

Gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane

Hexachlorobenzene

HeptachlorEpoxide

Mirex

Oxychlordane

p,p-DDE

Trans-nonachlor

2,5-dichlorophenolresult

2,4,6-trichlorophenolresult

Pentachlorophenol

Dimethylphosphate

Diethylphosphate

Dimethylthiophosphate

PCB66

PCB74

PCB99

PCB105

PCB118

PCB138&158

PCB146

PCB153

PCB156

PCB157

PCB167

PCB170

PCB172

PCB177

PCB178

PCB180

PCB183

PCB187

3,3,4,4,5,5-hxcb

3,3,4,4,5-pncb

3,4,4,5-tcb

Perfluoroheptanoicacid

Perfluorohexanesulfonicacid

Perfluorononanoicacid

Perfluorooctanoicacid

Perfluorooctanesulfonicacid

Perfluorooctanesulfonamide

2,3,7,8-tcdf

1,2,3,7,8-pncdf

2,3,4,7,8-pncdf

1,2,3,4,7,8-hxcdf

1,2,3,6,7,8-hxcdf

1,2,3,7,8,9-hxcdf

2,3,4,6,7,8-hxcdf

1,2,3,4,6,7,8-hpcdf

Measles

Toxoplasma

HepatitisAAntibody

HepatitisBcoreantibody

HepatitisBSurfaceAntibody

HerpesII

Albumin, urine

Uric acid

Phosphorus

Osmolality

Sodium

Potassium

Creatinine

Chloride

Total calcium

Bicarbonate

Blood urea nitrogen

Total protein

Total bilirubin

Lactate dehydrogenase LDH

Gamma glutamyl transferase

Globulin

Alanine aminotransferase ALT

Aspartate aminotransferase AST

Alkaline phosphotase

Albumin

Methylmalonic acid

PSA. total

Prostate specific antigen ratio

TIBC, Frozen Serum

Red cell distribution width

Red blood cell count

Platelet count SI

Segmented neutrophils percent

Mean platelet volume

Mean cell volume

Mean cell hemoglobin

MCHC

Hemoglobin

Hematocrit

Ferritin

Protoporphyrin

Transferrin saturation

White blood cell count

Monocyte percent

Lymphocyte percent

Eosinophils percent

C-reactive protein

Segmented neutrophils number

Monocyte number

Lymphocyte number

Eosinophils number

Basophils number

mean systolic

mean diastolic

60 sec. pulse:

60 sec HR

Total Cholesterol

Triglycerides

Glucose, serum

Insulin

Homocysteine

Glucose, plasma

Glycohemoglobin

C-peptide: SI

LDL-cholesterol

Direct HDL-Cholesterol

Bone alkaline phosphotase

Trunk Fat

Lumber Pelvis BMD

Lumber Spine BMD

Head BMD

Trunk Lean excl BMC

Total Lean excl BMC

Total Fat

Total BMD

Weight

Waist Circumference

Triceps Skinfold

Thigh Circumference

Subscapular Skinfold

Recumbent Length

Upper Leg Length

Standing Height

Head Circumference

Maximal Calf Circumference

Body Mass Index

-0.4 -0.2 0 0.2 0.4

Value

050100150

Color Key

and Histogram

Count

http://bit.ly.com/pemap

phenotypes

exposures

+-

nutrients

BMI,weight,

BMD

metabolic

renalfunction

pcbs

metabolic

bloodparameters

hydrocarbons

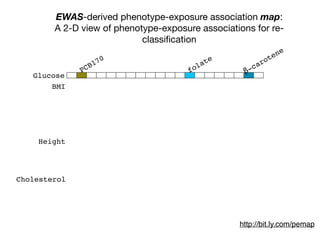

EWAS-derived phenotype-exposure association map:

A 2-D view of connections between P and E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-113-320.jpg)

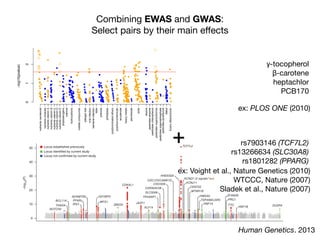

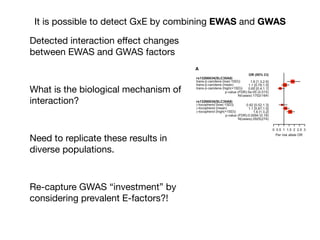

![Per-risk allele OR for rs13266634 (SLC30A8) Stratified by E

Increase or decrease up to 30-40% vs. marginal effect!

Adjusted for race, sex, BMI, age

trans-β-carotene (low(-1SD))

trans-β-carotene (mean)

trans-β-carotene (high(+1SD))

γ-tocopherol (low(-1SD))

γ-tocopherol (mean)

γ-tocopherol (high(+1SD))

rs13266634(SLC30A8)

rs13266634(SLC30A8)

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5

Per risk allele OR

OR (95% CI)

1.8 [1.3,2.6]

1.1 [0.79,1.5]

0.65 [0.4,1.1]

p-value:5e-05

N(cases):1702(164)

0.82 [0.52,1.3]

1.1 [0.87,1.5]

1.6 [1.3,2]

p-value:0.0094

N(cases):2925(274)

marginal OR=1.1

trans-β-carotene (low(-1SD))

trans-β-carotene (mean)

trans-β-carotene (high(+1SD))

γ-tocopherol (low(-1SD))

γ-tocopherol (mean)

γ-tocopherol (high(+1SD))

rs13266634(SLC30A8)

rs13266634(SLC30A8)

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5

Per risk allele OR

OR (95% CI)

1.8 [1.3,2.6]

1.1 [0.79,1.5]

0.65 [0.4,1.1]

p-value:5e-05

N(cases):1702(164)

0.82 [0.52,1.3]

1.1 [0.87,1.5]

1.6 [1.3,2]

p-value:0.0094

N(cases):2925(274)

FDR=2%

FDR=18%

Human Genetics. 2013](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-126-320.jpg)

![In conclusion:

on GWAS and EWAS

GWAS has been unparalleled in biological discovery...

... coupled with EWAS, will lead to precise and personal

medicine.

−log10(pvalue)

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●● ●

●●

●

●

●

● ●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●●

●

●●

●

●●

●

●

●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●●

●●

●

●

●

●

●

● ●

acrylamide

allergentest

bacterialinfection

cotinine

diakyl

dioxins

furansdibenzofuran

heavymetals

hydrocarbons

latex

nutrientscarotenoid

nutrientsminerals

nutrientsvitaminA

nutrientsvitaminB

nutrientsvitaminC

nutrientsvitaminD

nutrientsvitaminE

pcbs

perchlorate

pesticidesatrazine

pesticideschlorophenol

pesticidesorganochlorine

pesticidesorganophosphate

pesticidespyrethyroid

phenols

phthalates

phytoestrogens

polybrominatedethers

polyflourochemicals

viralinfection

volatilecompounds

012

to a doubling of the number of associated variants discov-

ered. The proportion of genetic variation explained by

significantly associated SNPs is usually low (typically less

than 10%) for many complex traits, but for diseases such

as CD and multiple sclerosis (MS [MIM 126200]), and for

quantitative traits such as height and lipid traits, between

10% and 20% of genetic variance has been accounted for

(Table 1). In comparison to the pre-GWAS era, the propor-

tion of genetic variation accounted for by newly discov-

ered variants that are segregating in the population is large.

It is clear that for most complex traits that have been

investigated by GWAS, multiple identified loci have

genome-wide statistical significance, and thus it is likely

that there are (many) other loci that have not been identi-

fied because of a lack of statistical significance (false nega-

tives). Recently, researchers have developed and applied

methods to quantify the proportion of phenotypic varia-

Figure 1. GWAS Discoveries over Time

Data obtained from the Published GWAS Catalog (see Web

Resources). Only the top SNPs representing loci with association

p values < 5 3 10À8

are included, and so that multiple counting

is avoided, SNPs identified for the same traits with LD r2

> 0.8 esti-

mated from the entire HapMap samples are excluded.

Figure 2. Increase in Number of Loci Identified as a Function of

Experimental Sample Size

(A) Selected quantitative traits.

(B) Selected diseases.

The coordinates are on the log scale. The complex traits were

selected with the criteria that there were at least three GWAS

papers published on each in journals with a 2010–2011 journal](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bmi7011212015-151210222642/85/Intro-to-Biomedical-Informatics-701-131-320.jpg)