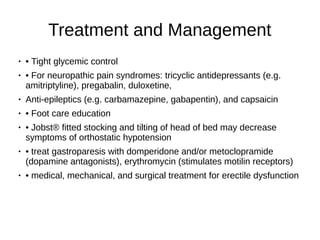

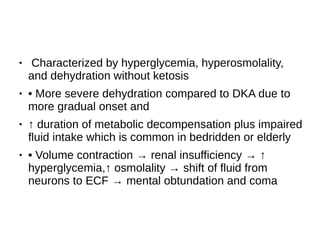

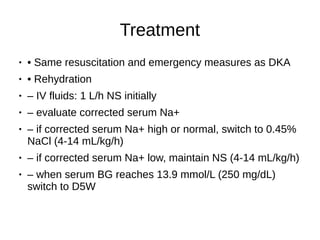

This document provides an overview of hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS). It describes the pathophysiology, clinical features, and treatment of HHS. HHS occurs in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and is often precipitated by various medical conditions and medications. It is characterized by severe hyperglycemia, hyperosmolality, and dehydration without ketosis. Treatment involves fluid resuscitation and insulin therapy. The document also reviews macrovascular and microvascular complications of diabetes, including retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy.

![● • K+ replacement

● – less severe K+ depletion compared to DKA

● – if serum K+ <3.3 mmol/L, give 40 mEq/L K+

replacement and hold insulin

● until [K+] ≥3.3mmol/L

● – when K+ 3.3-5.0 mmol/L add KCL 10-40 mEq/L

to keep K+ in the range of 3.5-5 mEq/L

● – if serum K+ ≥5.5 mmol/L, check K+ every 2 h](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/internalmeddm-221031174207-e5e69916/85/Internal-Med-DM-pdf-7-320.jpg)