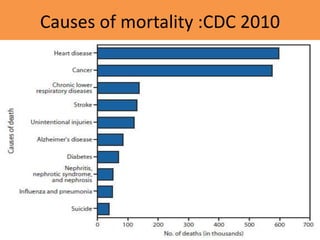

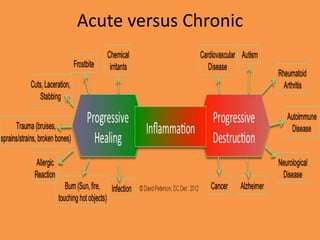

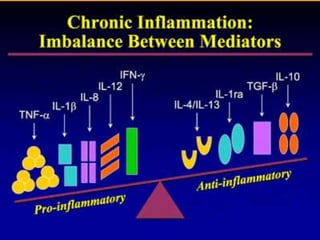

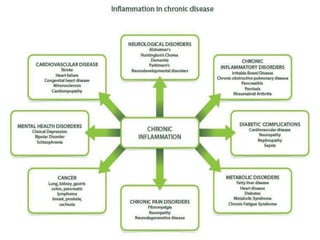

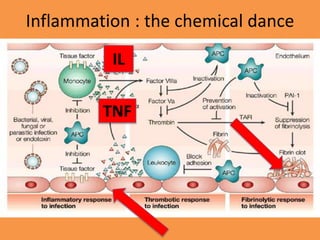

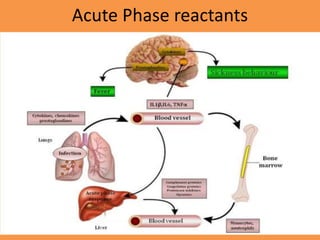

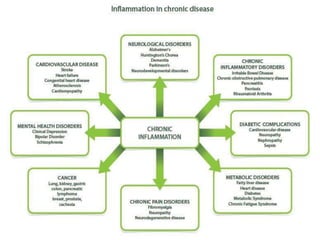

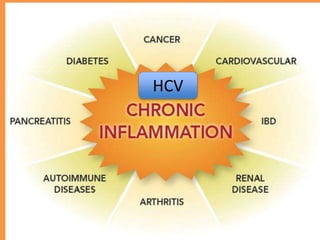

This document discusses inflammation and its role in various disease processes. Some key points include:

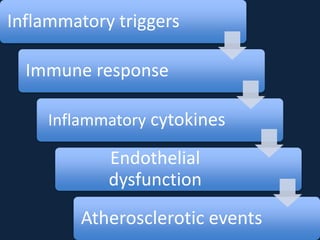

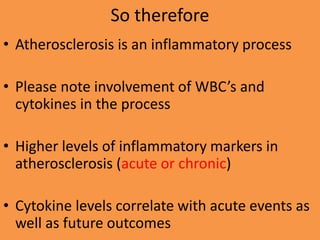

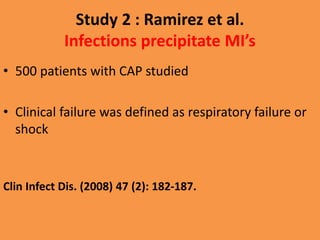

- Inflammation plays a role in many leading causes of death like heart attacks and strokes. It is also involved in atherosclerosis and is considered an inflammatory process.

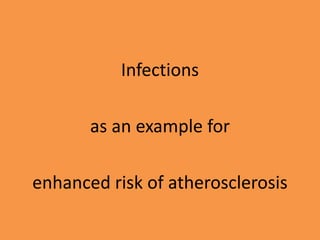

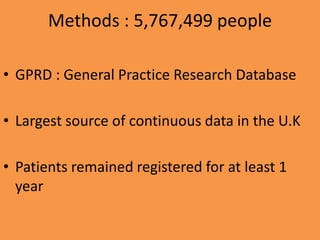

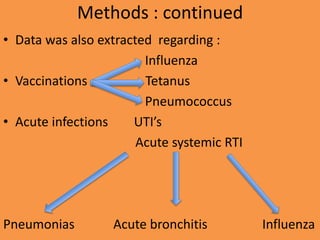

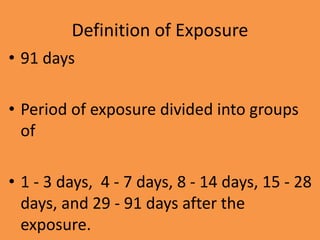

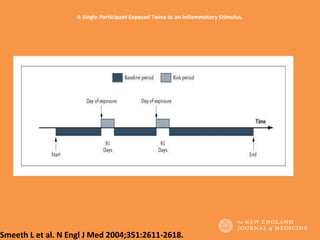

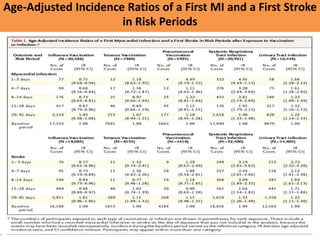

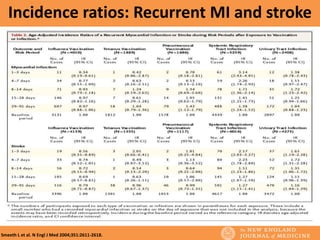

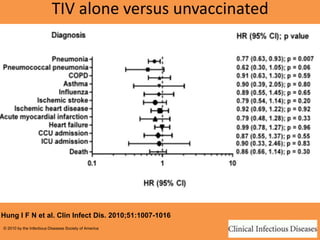

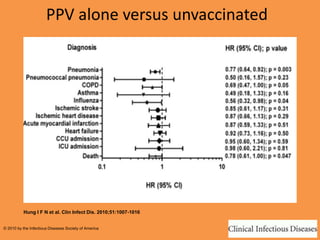

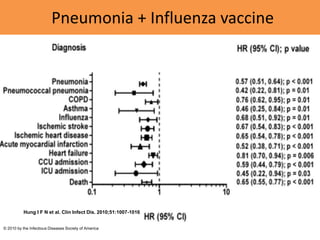

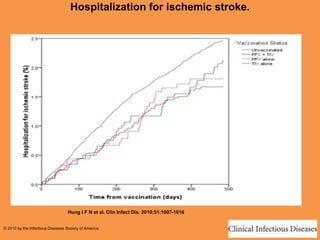

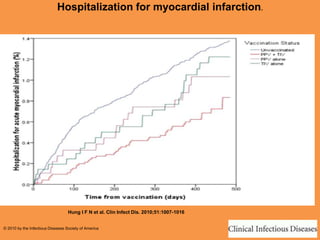

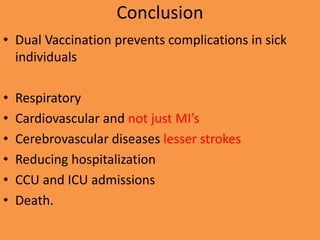

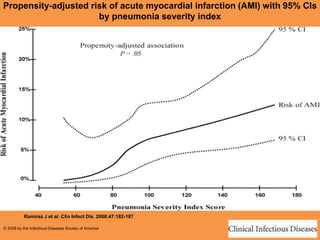

- Acute infections can transiently increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes by enhancing inflammation. However, vaccines do not have this effect and may even help reduce risk.

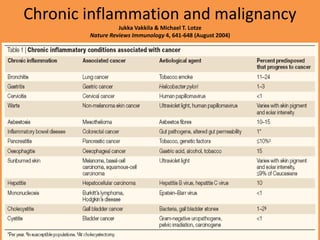

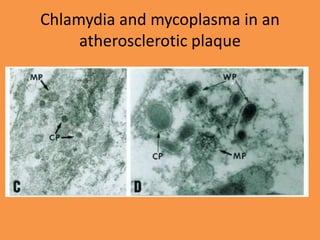

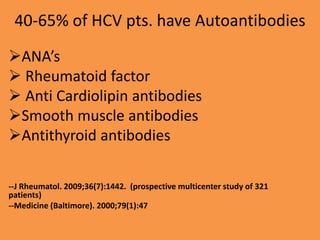

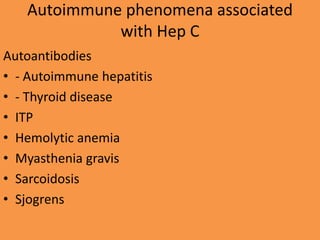

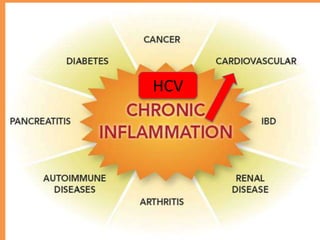

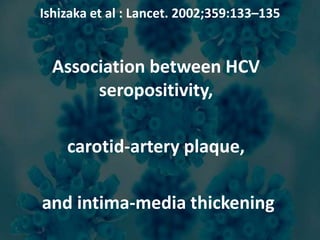

- Chronic infections like hepatitis C and periodontal disease are associated with higher levels of inflammation and worse plaque in arteries. This suggests they may exacerbate atherosclerosis.

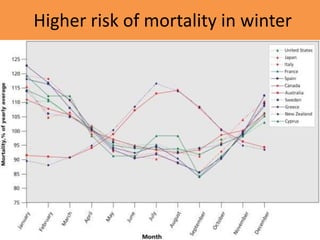

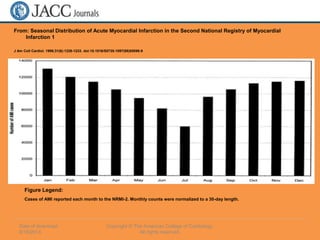

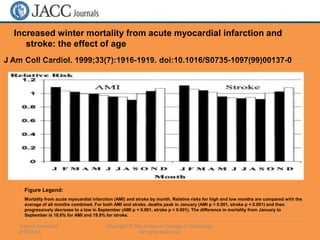

- Inflammation varies seasonally, with more heart attacks and strokes occurring in winter months when respiratory infection rates are highest

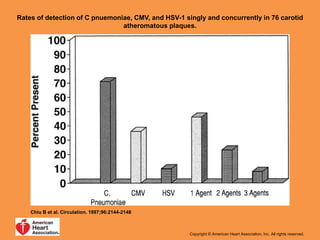

![Results

• C pneumoniae detected in 71%

(95% confidence interval [CI], 59.5% to 80.9%)

• CMV was detected in 35.5%

(CI, 24.9% to 47.3%)

• HSV-1 10.5%

(CI, 4.7% to 19.7%)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inflammation-140823155002-phpapp02/85/Inflammation-atherosclerosis-cancer-obesity-infections-dementia-depression-62-320.jpg)

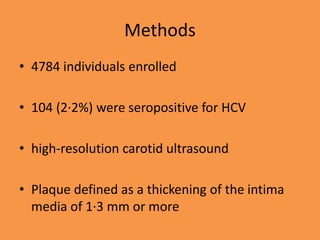

![Results

• Plaques were twice as common in

seropositives

40 of 1070 [3·7%] vs 64 of 3714 [1·7%]

• Intima-media thickening 4 times as common

(38 of 605 [6·3%] and 66 of 4179 [1·6%]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inflammation-140823155002-phpapp02/85/Inflammation-atherosclerosis-cancer-obesity-infections-dementia-depression-81-320.jpg)

![Odds ratio and p values

• Increased risk of carotid-artery plaque

(odds ratio 1.92 [95% CI 1.56-2.38], p=0.002)

• Also with carotid intima-media thickening

(odds ratio 2.85 [2.28-3.57], p<0.0001)

Evidence was irrespective of known

atherogenic risk factors

---Ishizaka et al : Lancet. 2002;359:133–135](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/inflammation-140823155002-phpapp02/85/Inflammation-atherosclerosis-cancer-obesity-infections-dementia-depression-82-320.jpg)