We are very happy to publish this issue of the International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research. The International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research is a peer-reviewed open-access journal committed to publishing high-quality articles in the field of education. Submissions may include full-length articles, case studies and innovative solutions to problems faced by students, educators and directors of educational organisations. To learn more about this journal, please visit the website http://www.ijlter.org. We are grateful to the editor-in-chief, members of the Editorial Board and the reviewers for accepting only high quality articles in this issue. We seize this opportunity to thank them for their great collaboration. The Editorial Board is composed of renowned people from across the world. Each paper is reviewed by at least two blind reviewers. We will endeavour to ensure the reputation and quality of this journal with this issue.

![64

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

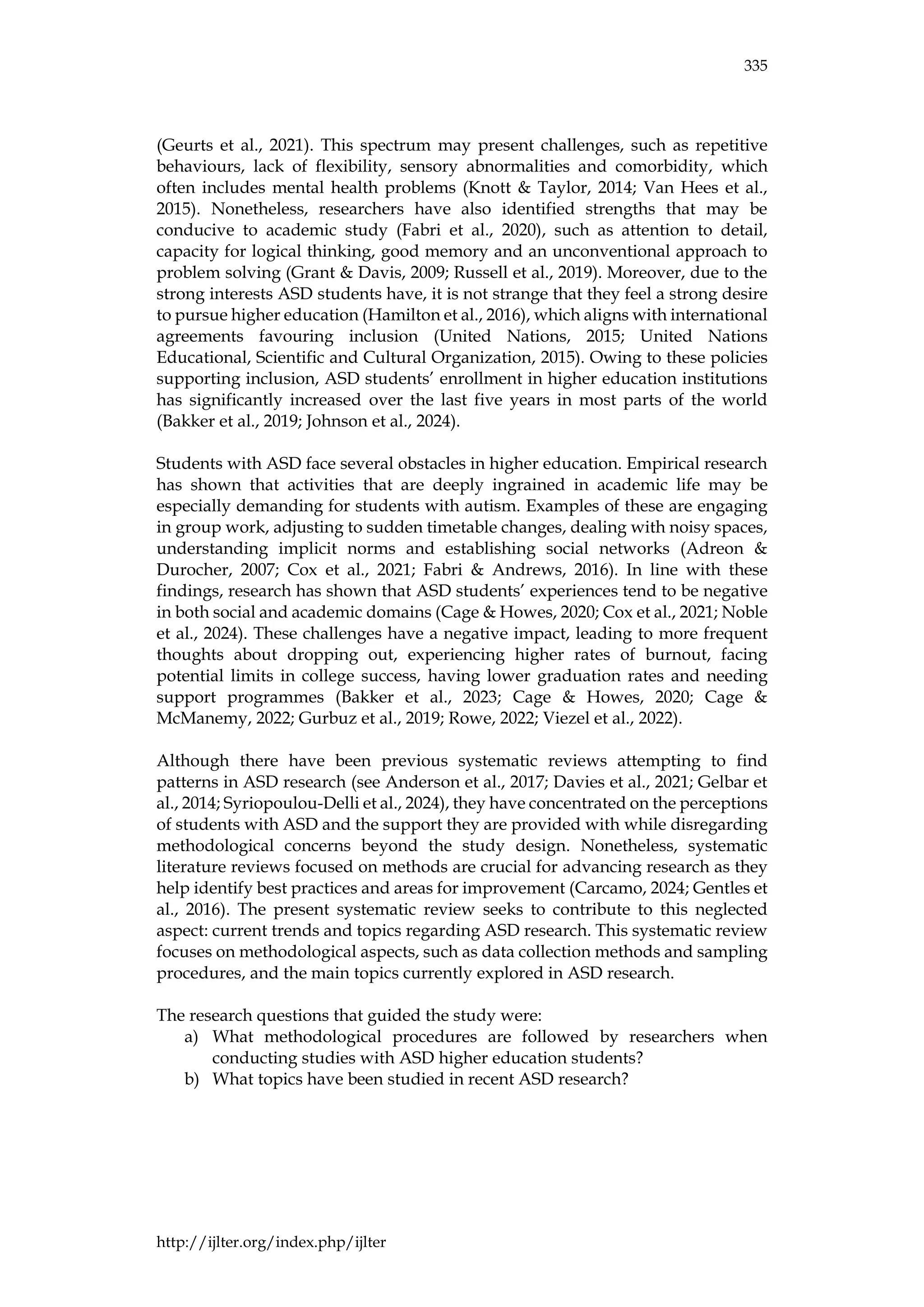

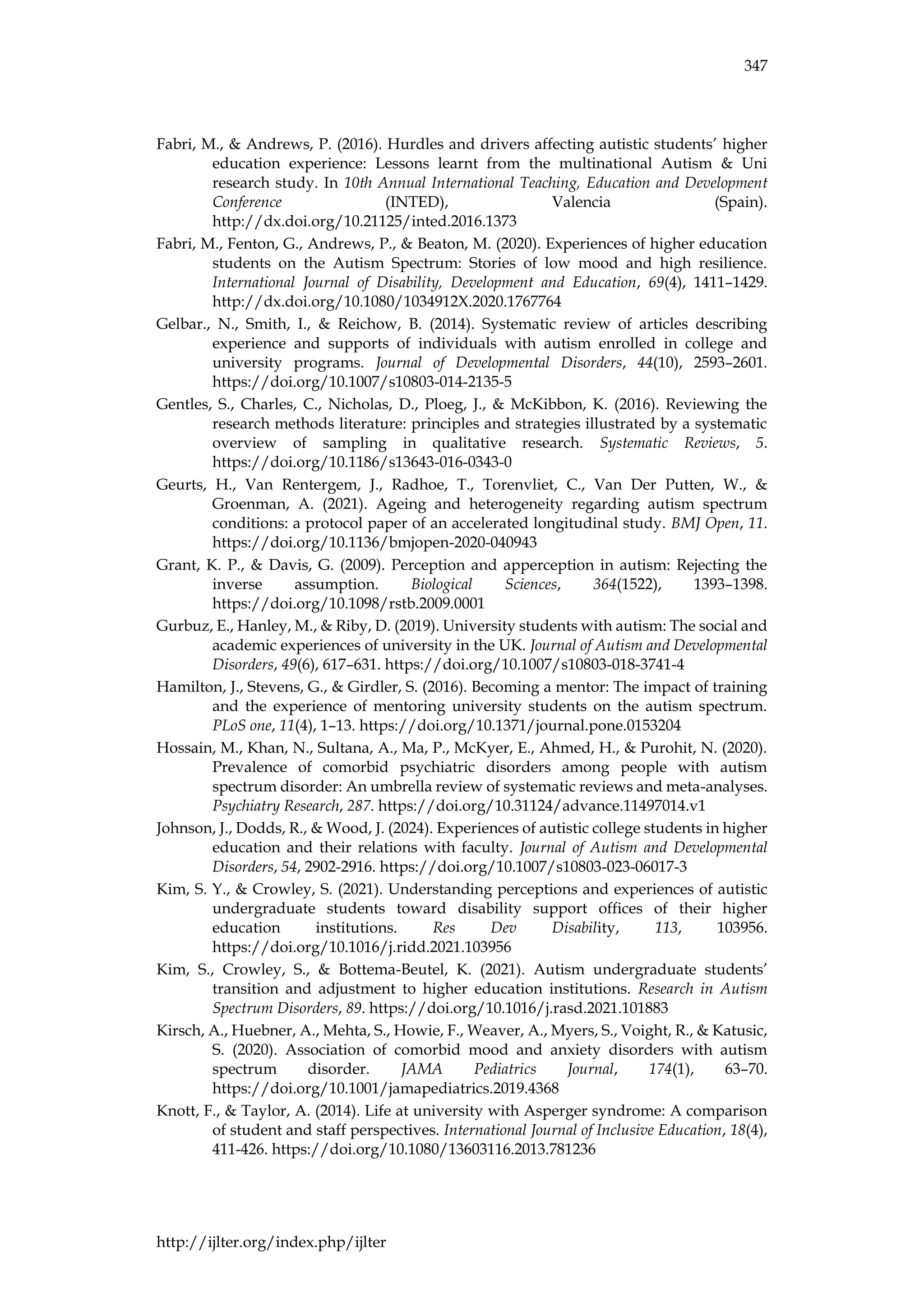

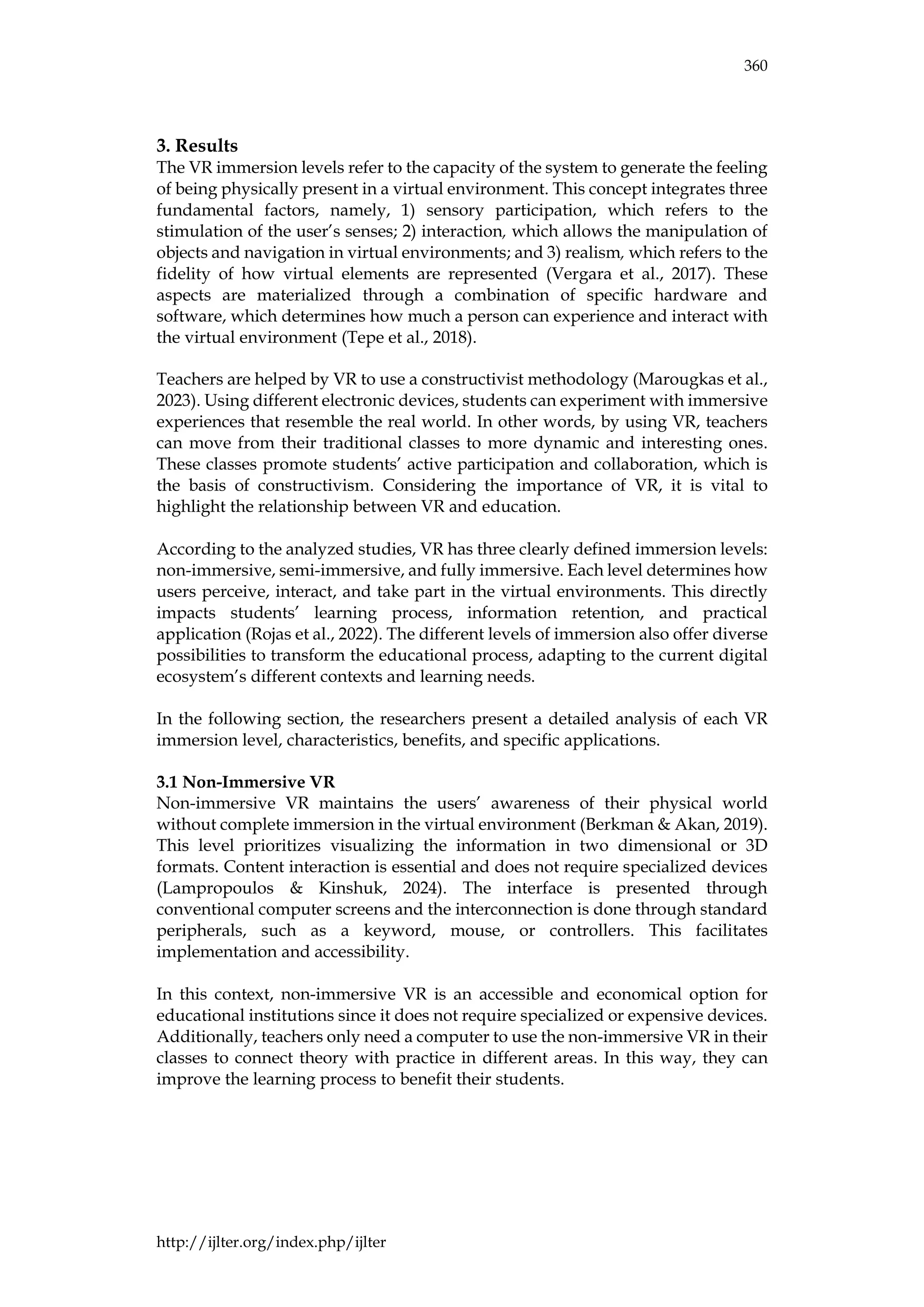

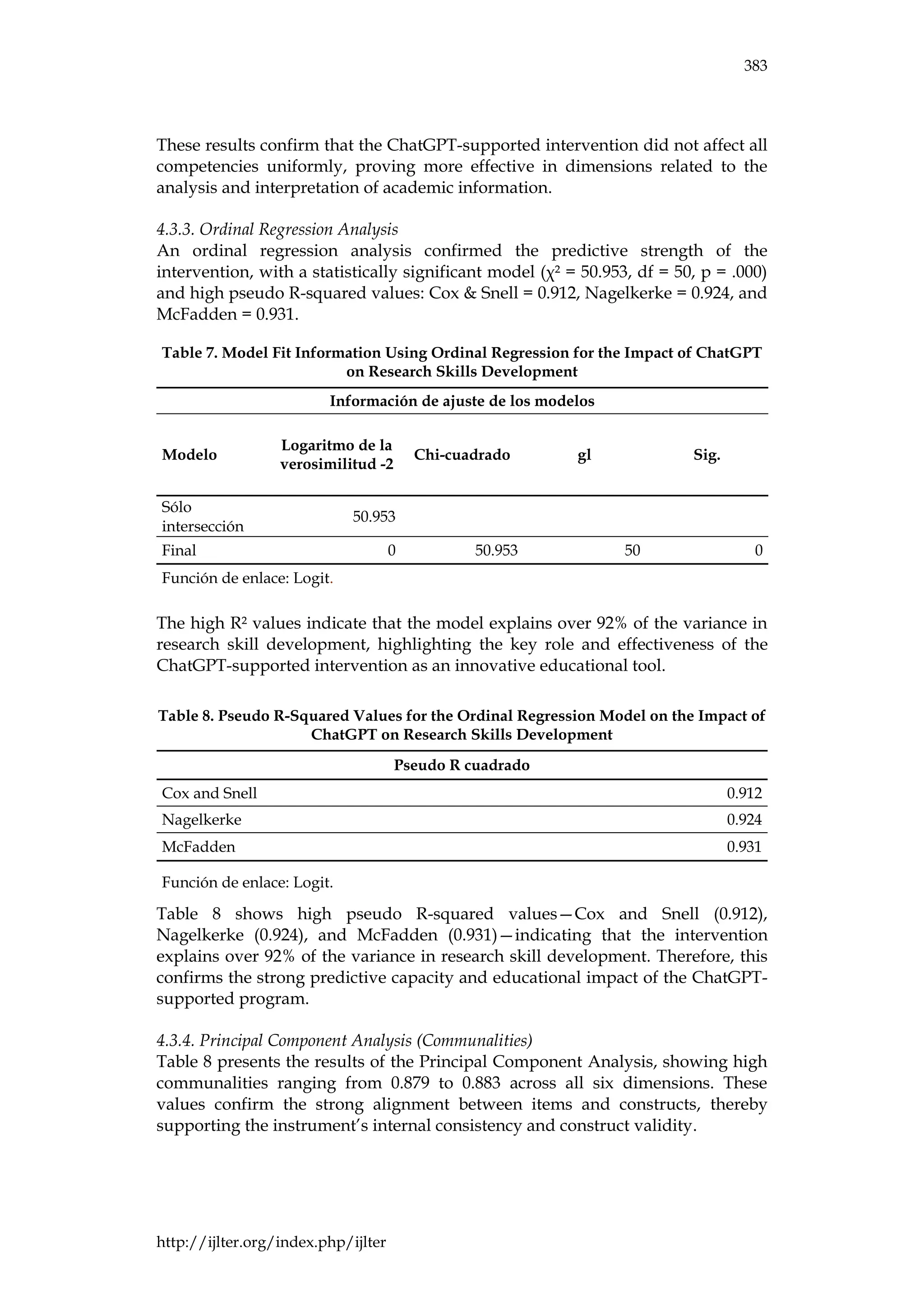

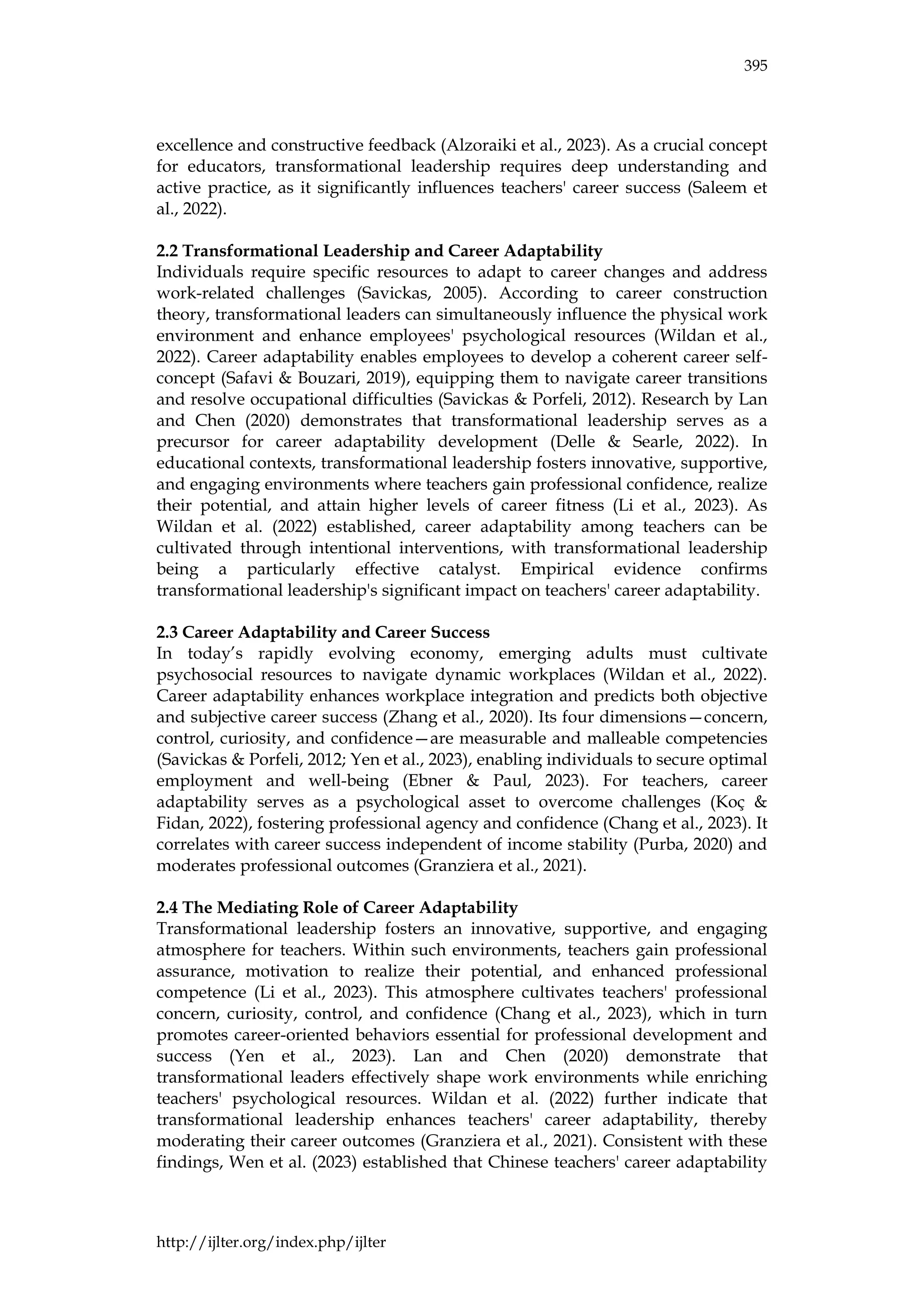

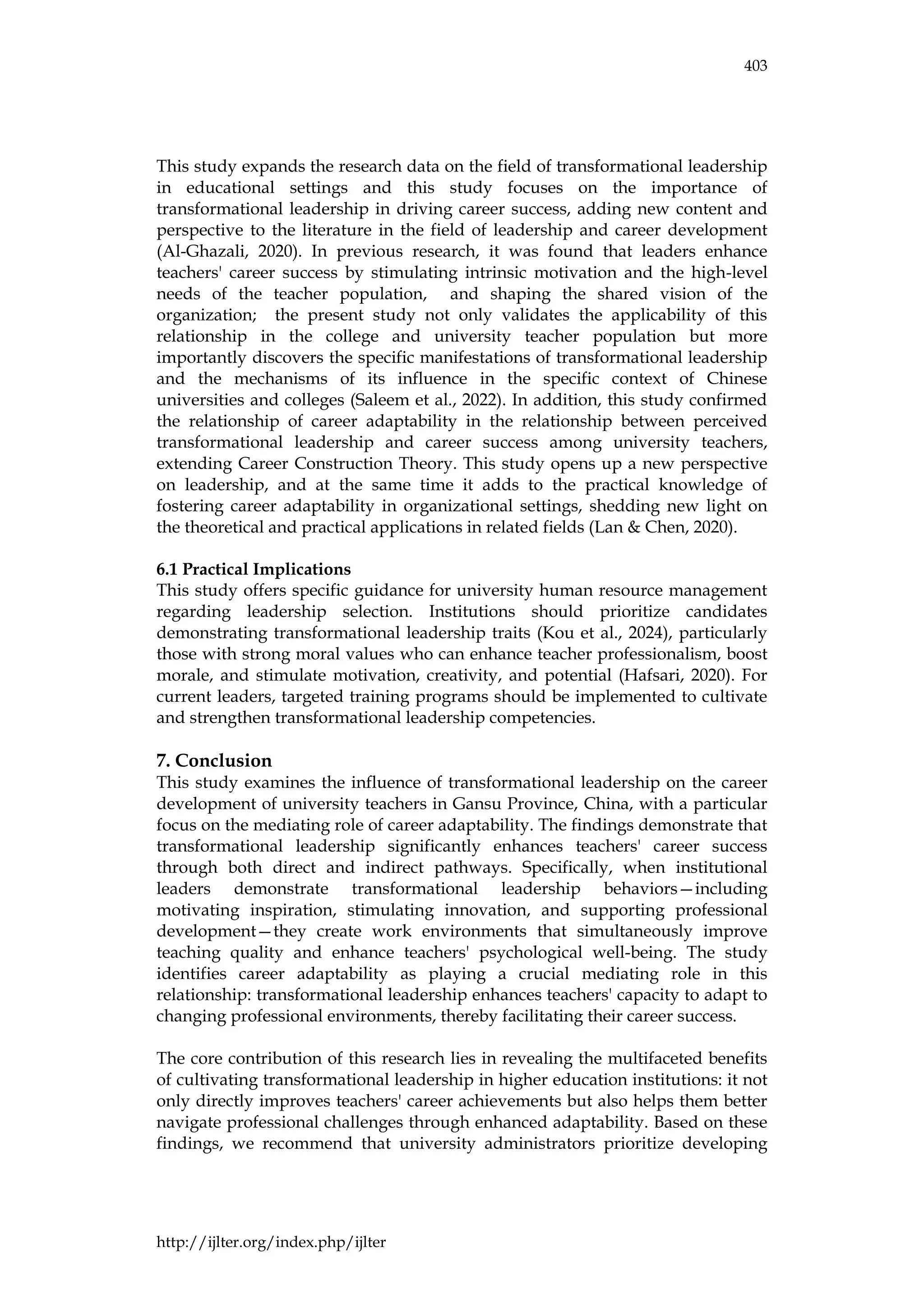

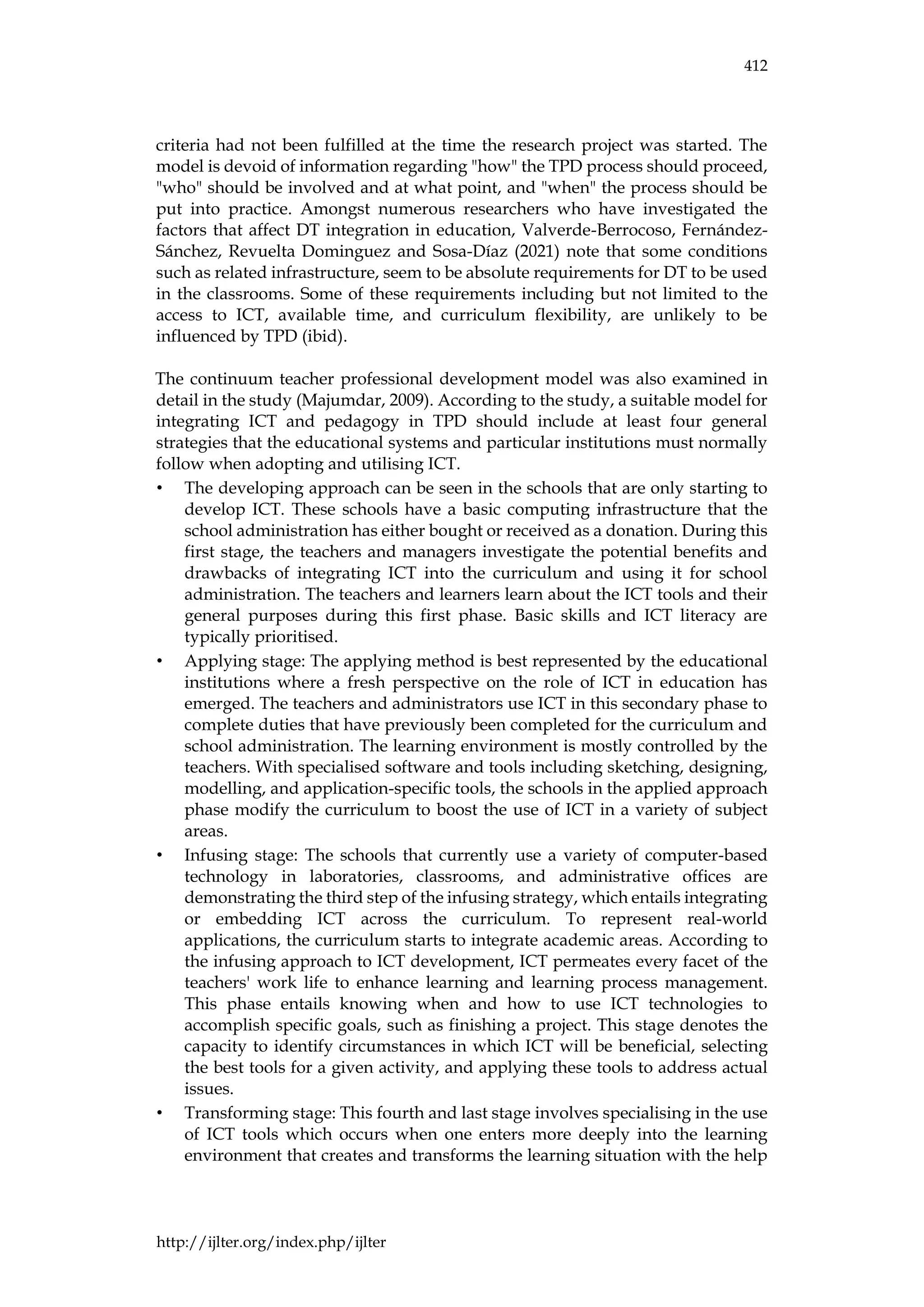

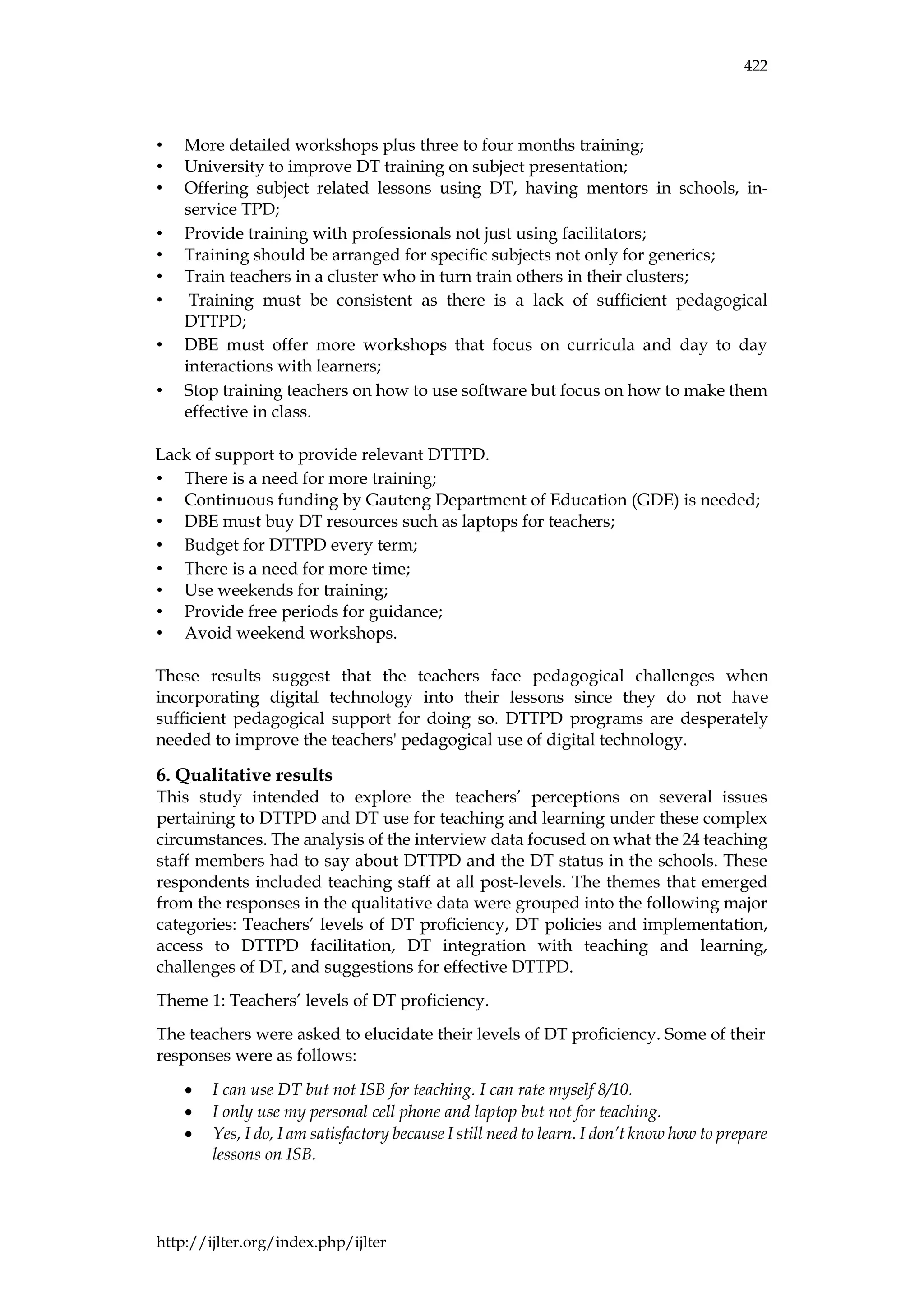

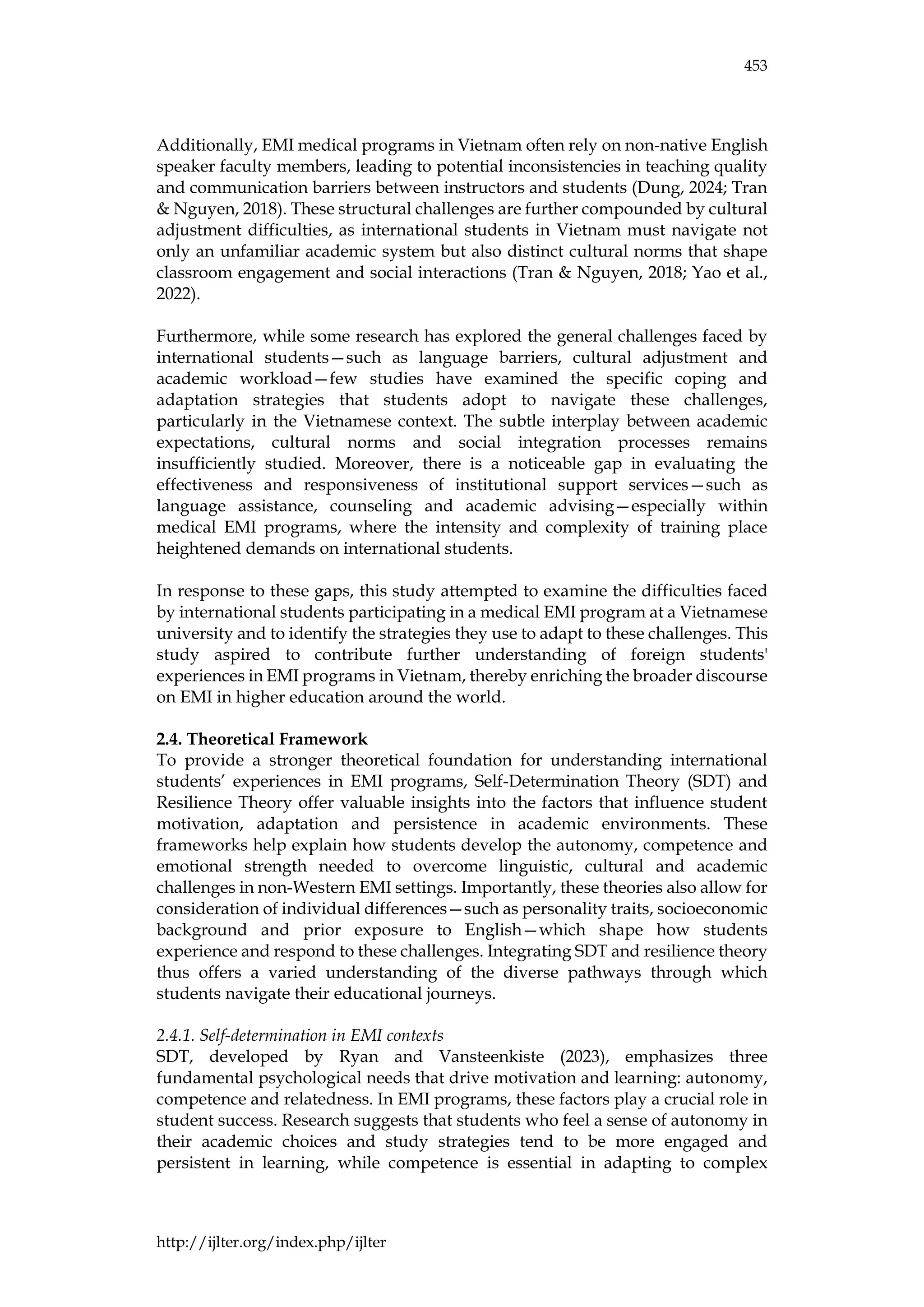

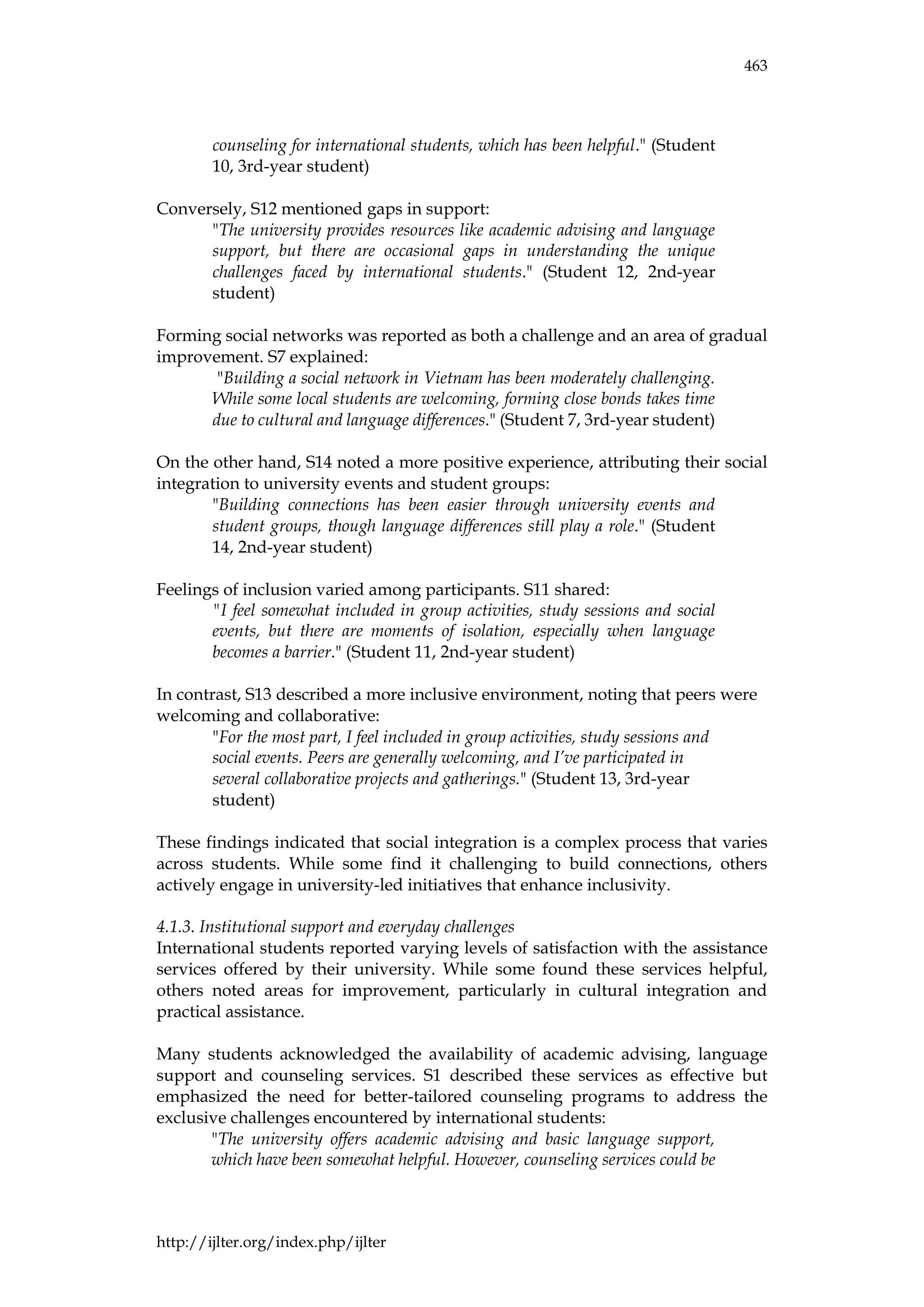

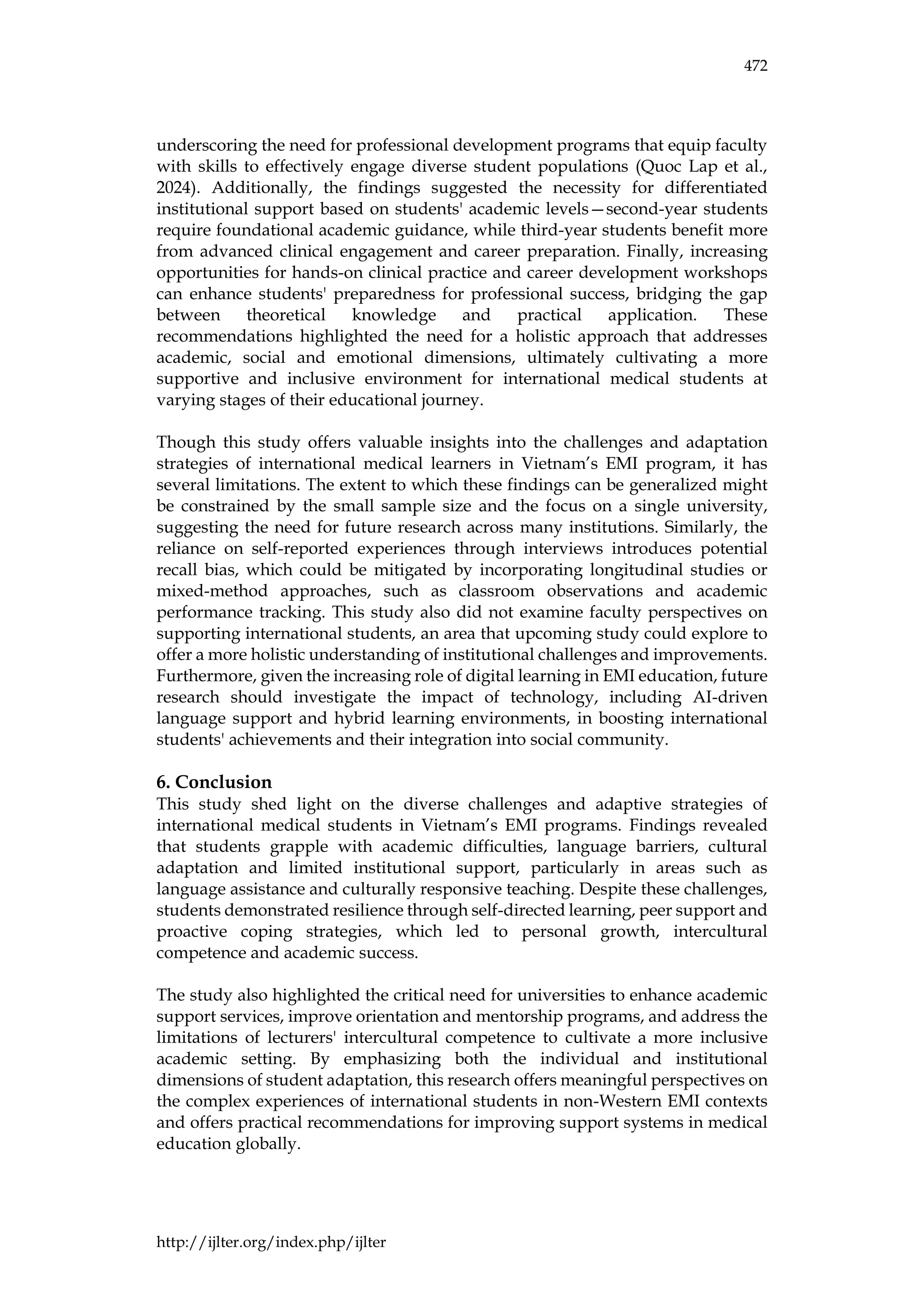

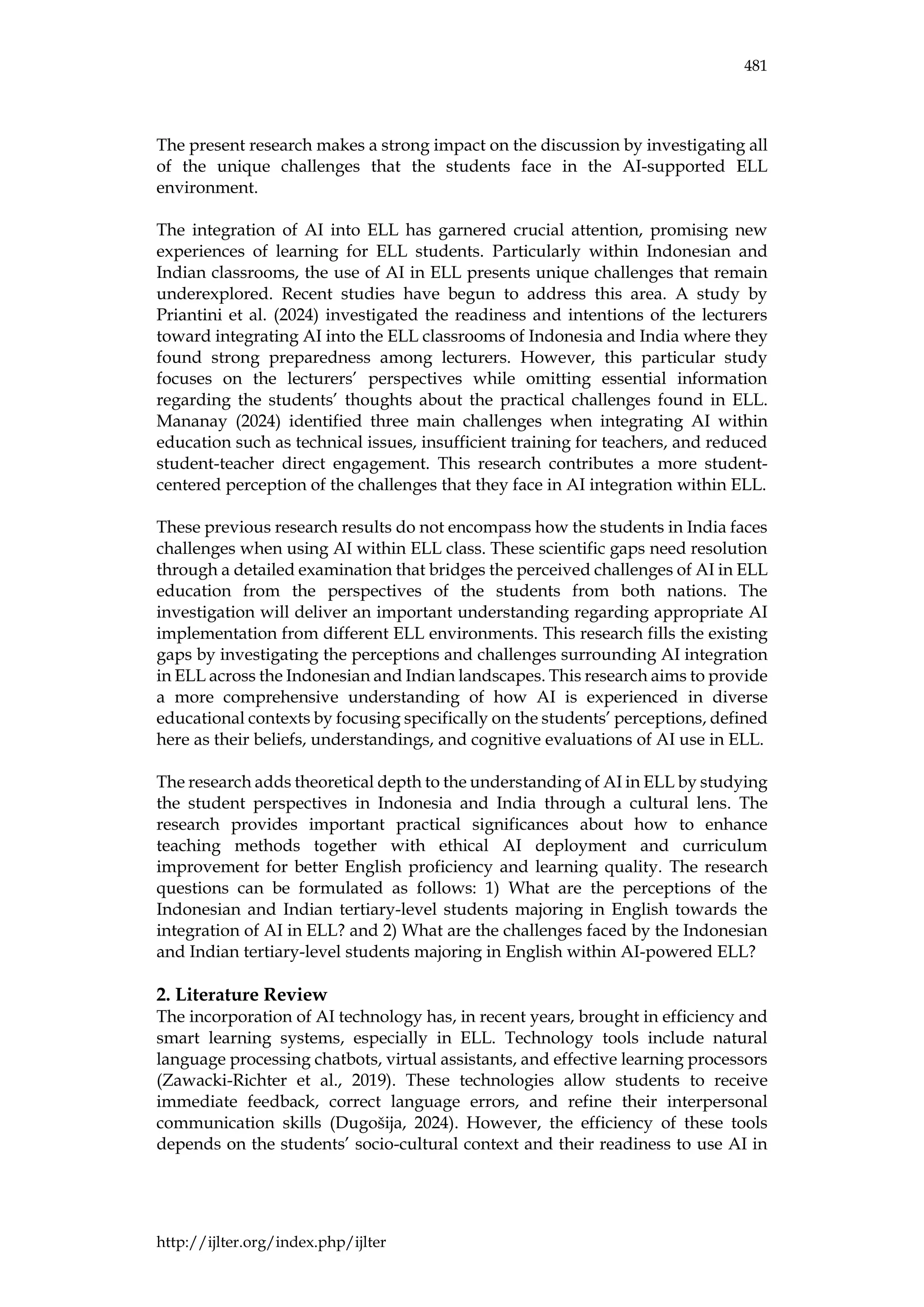

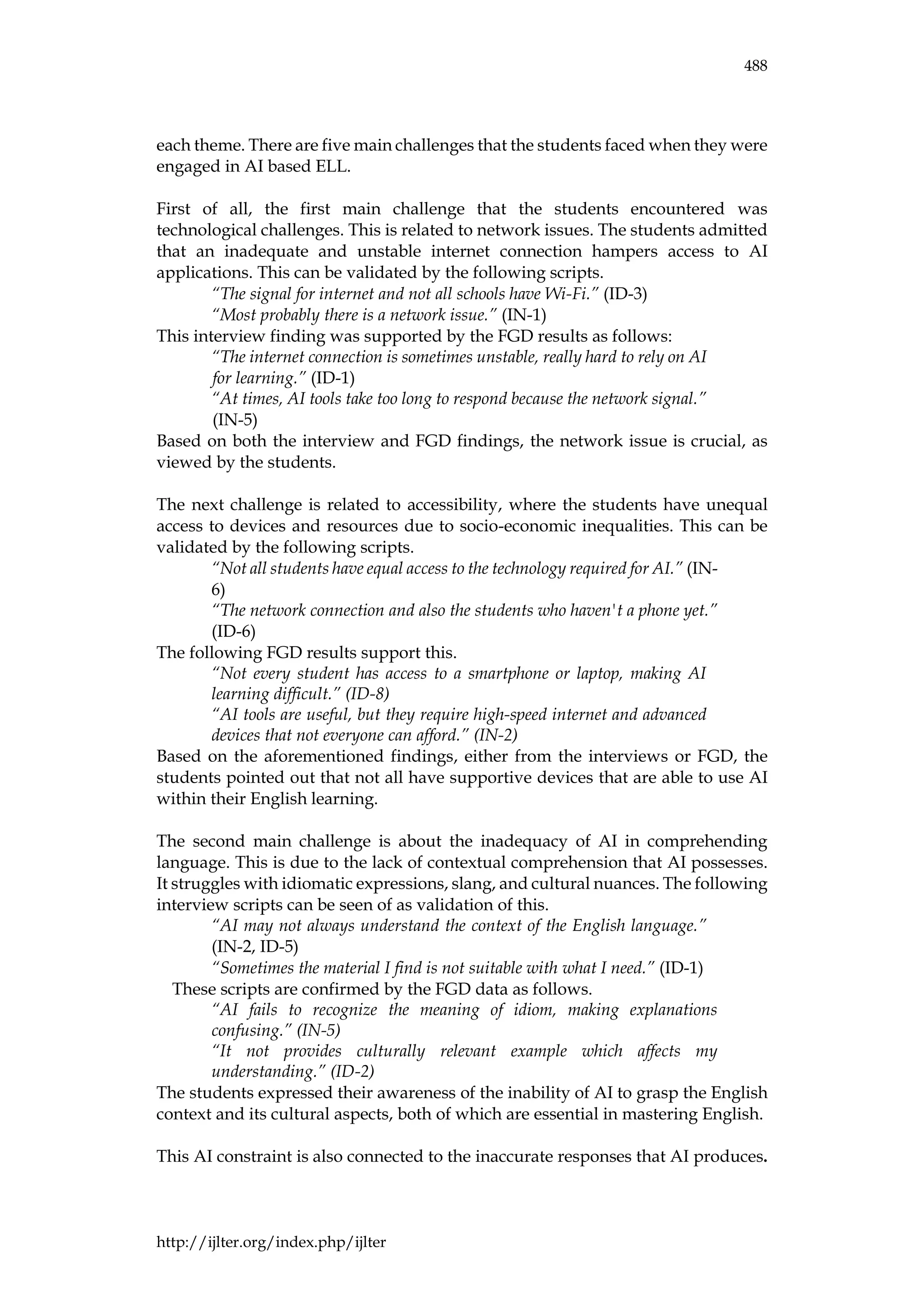

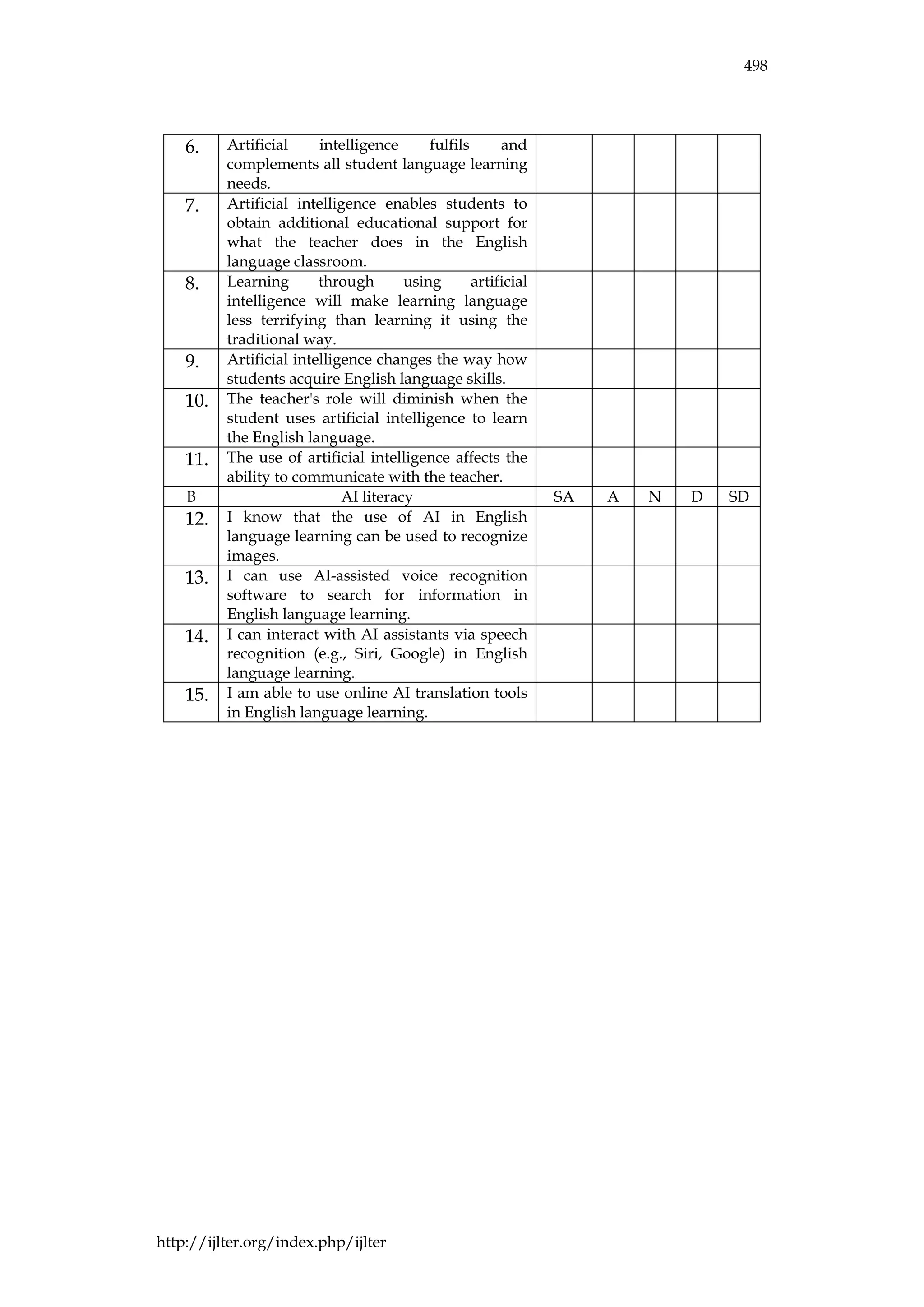

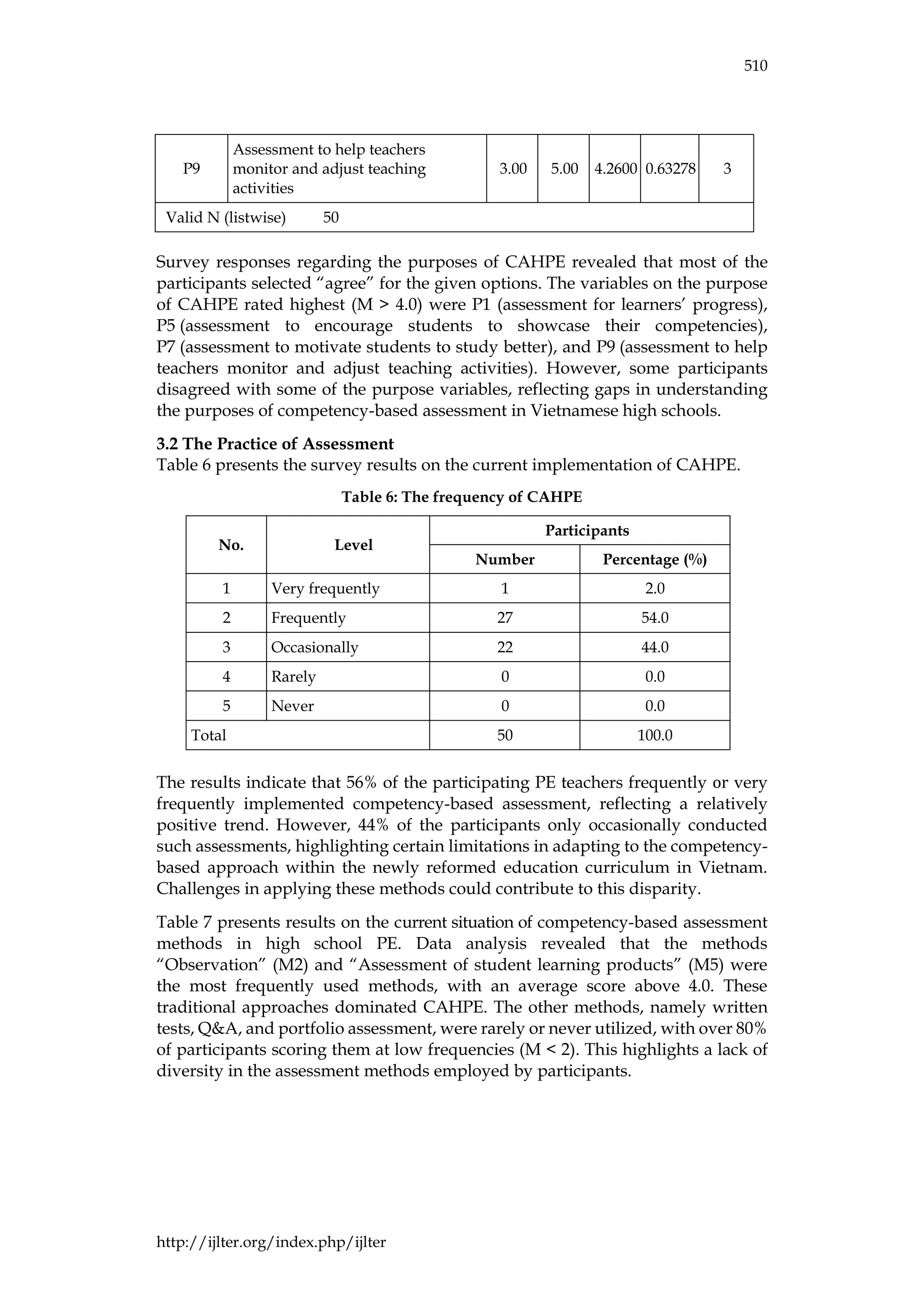

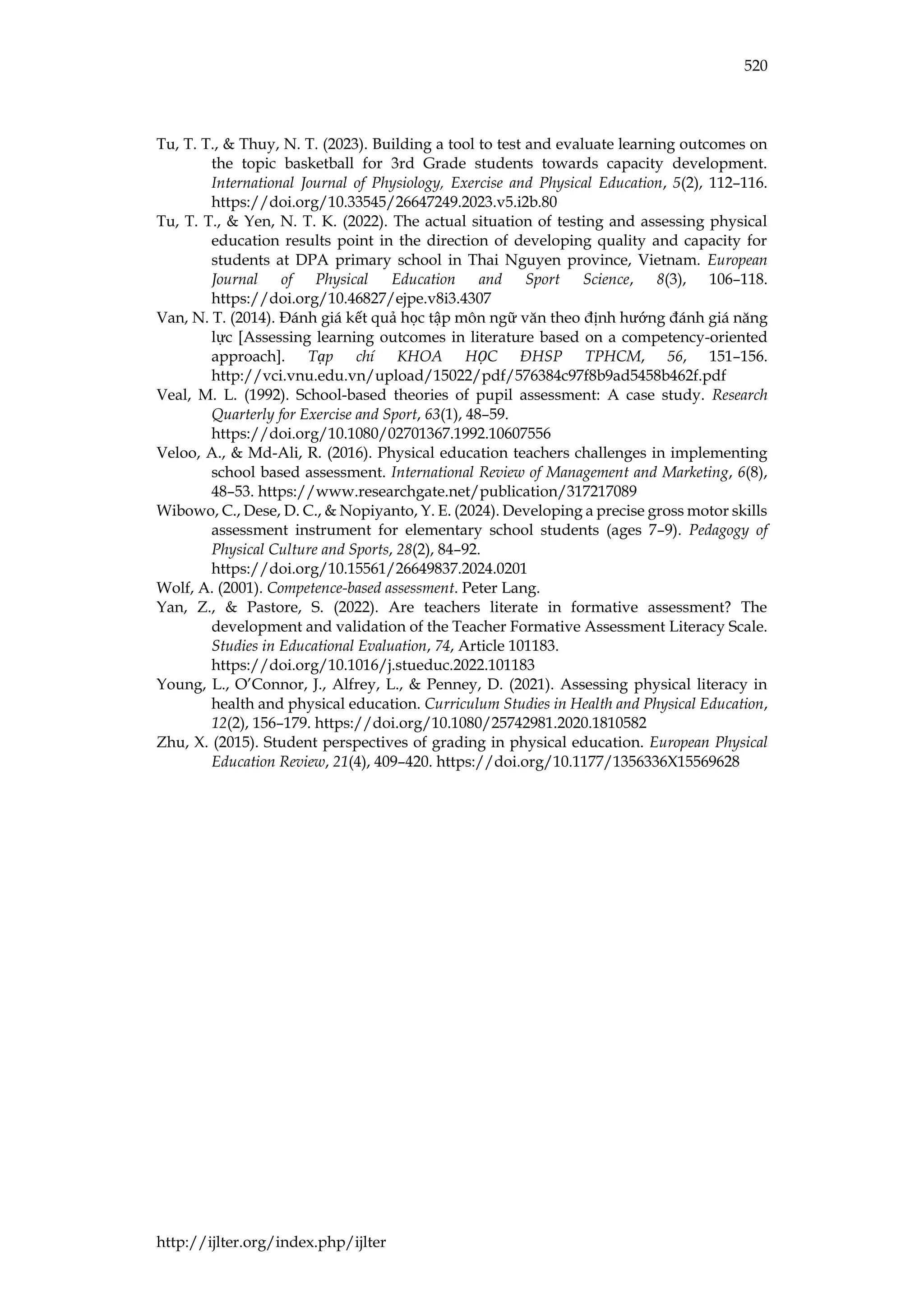

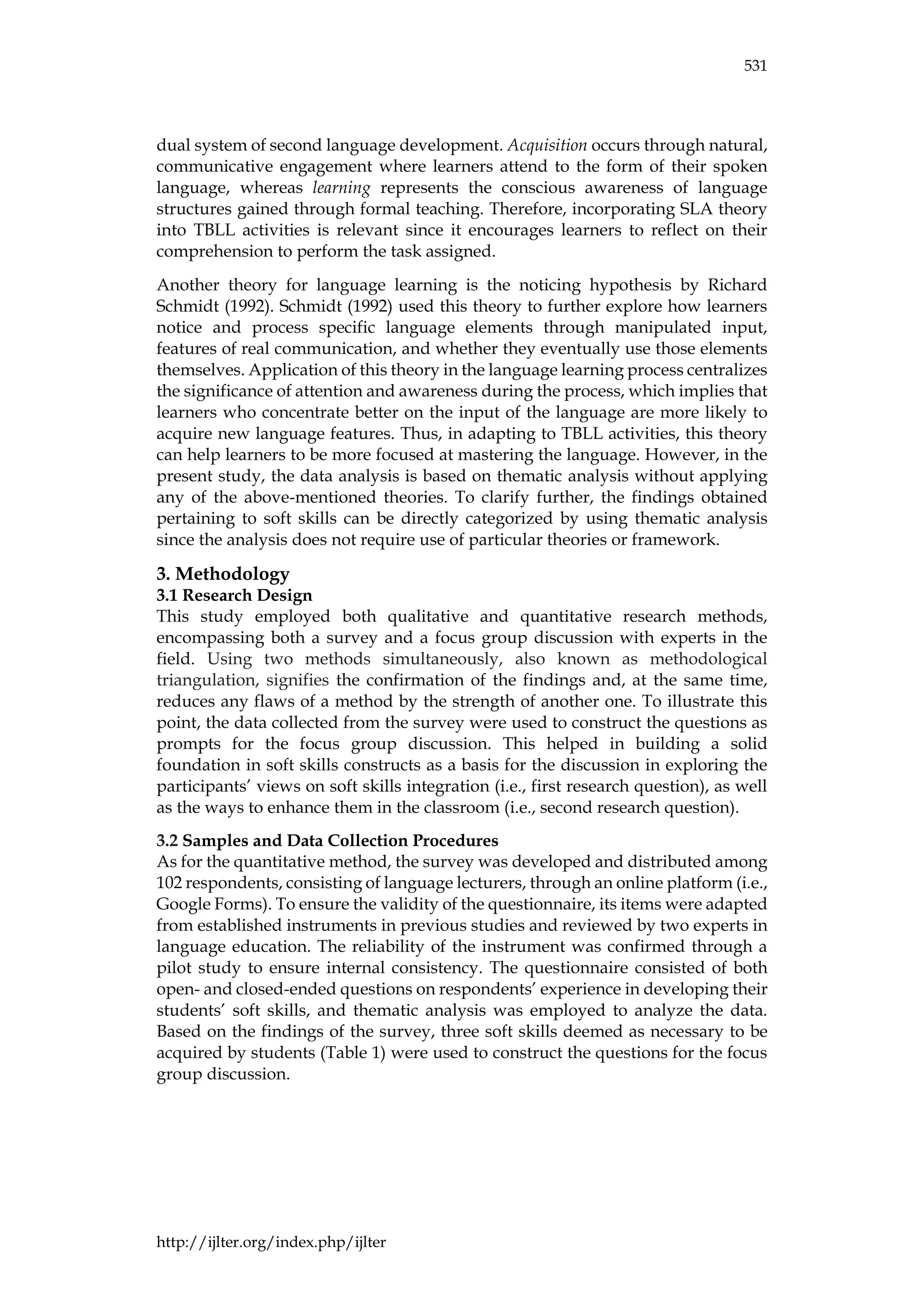

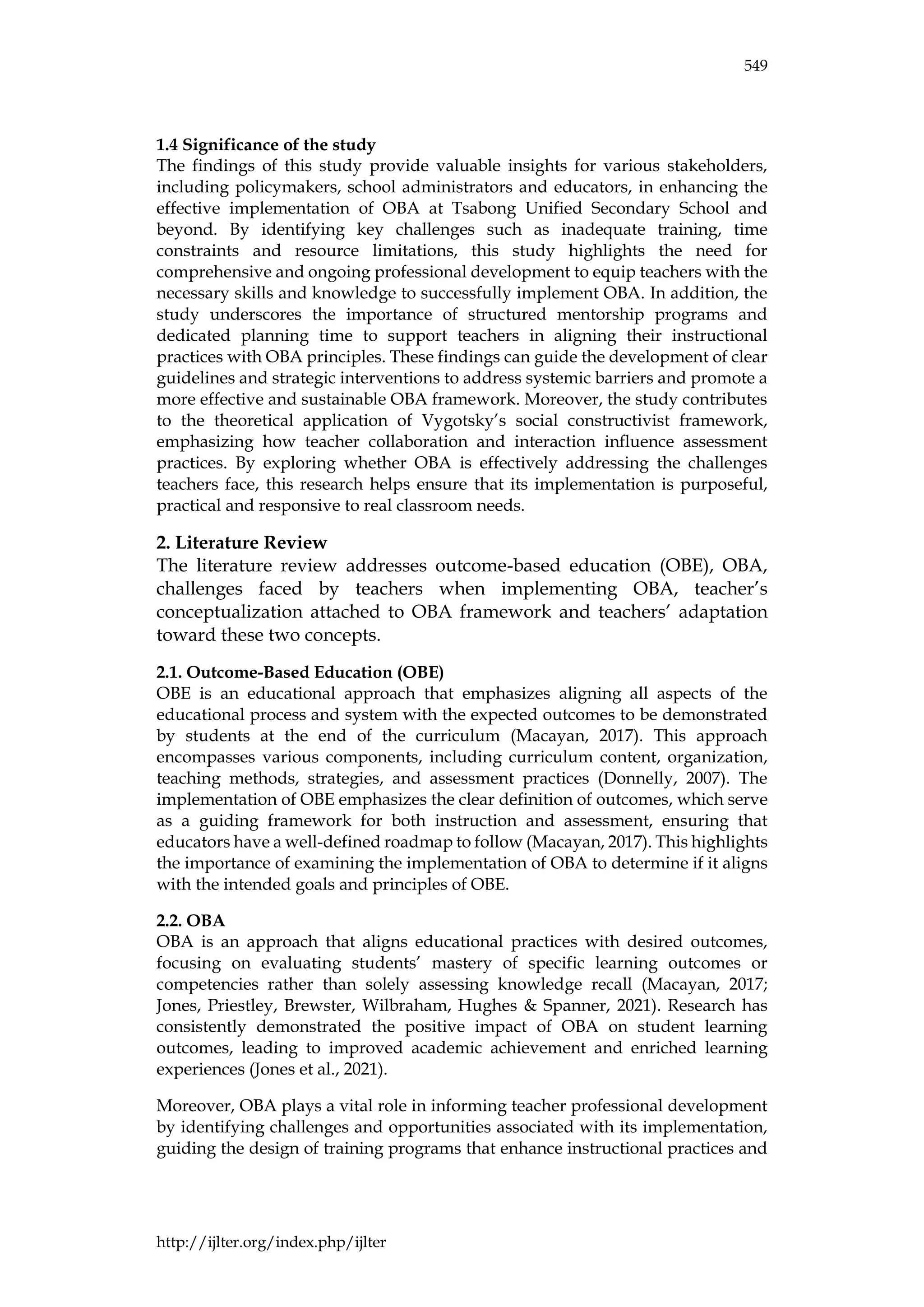

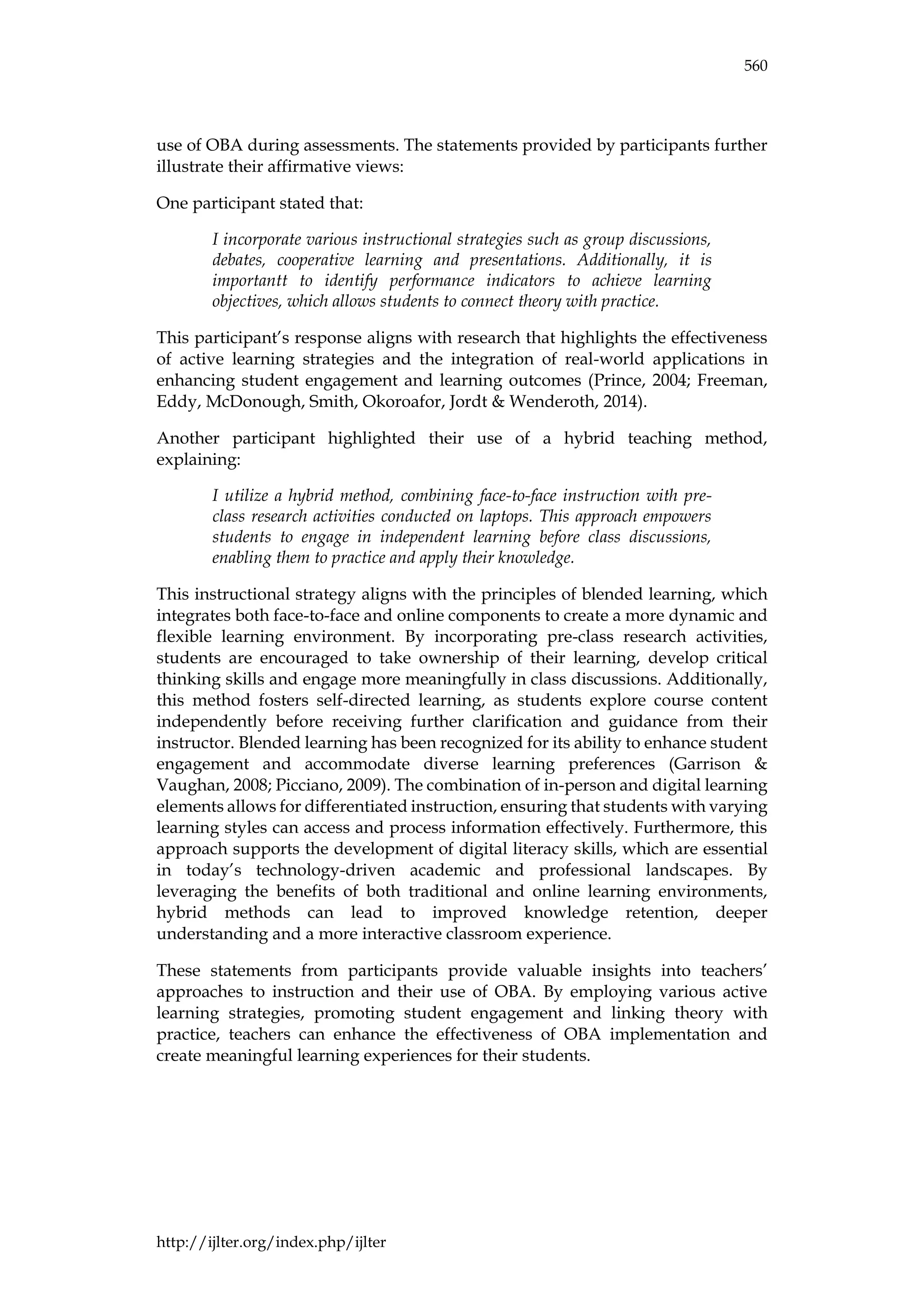

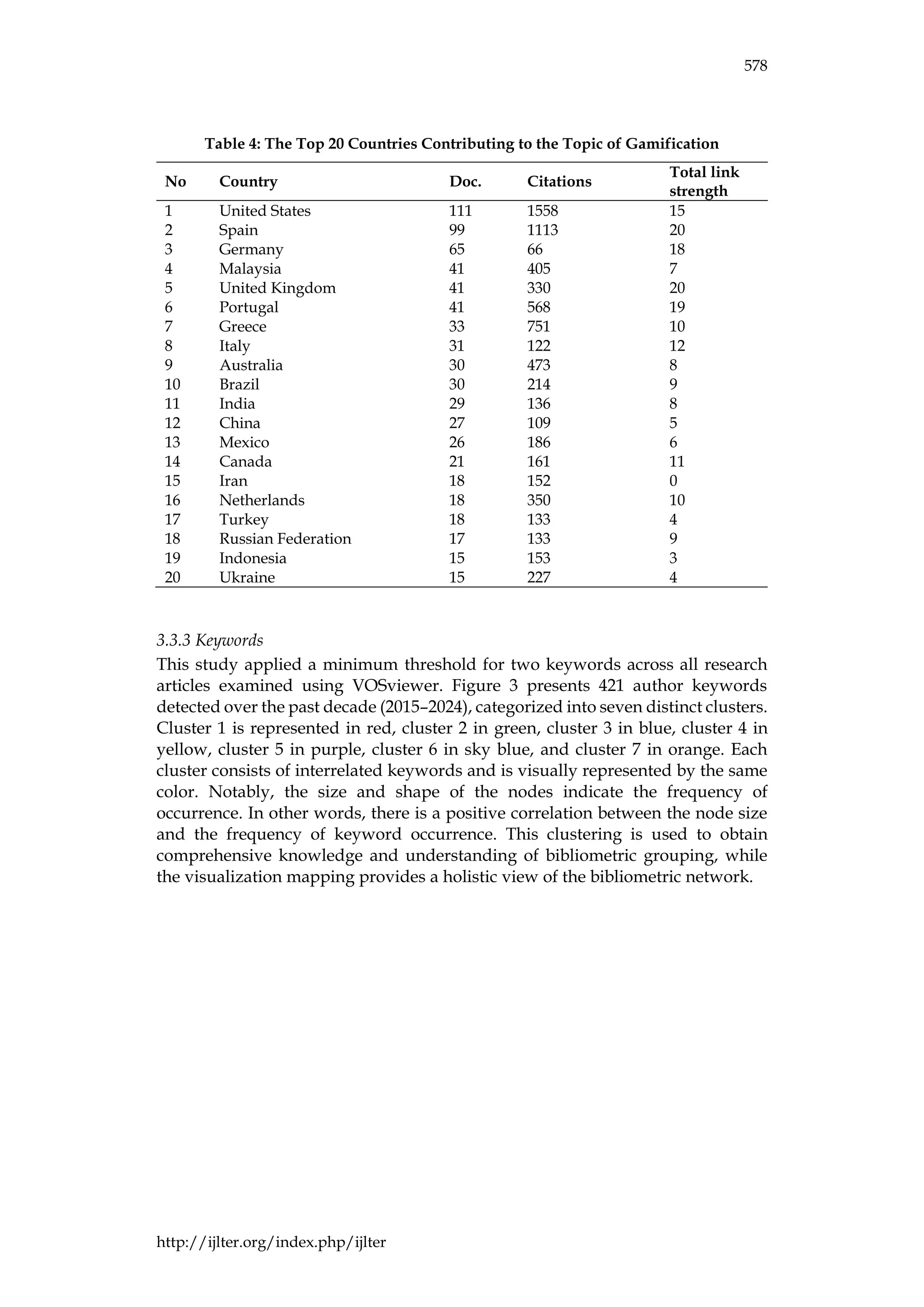

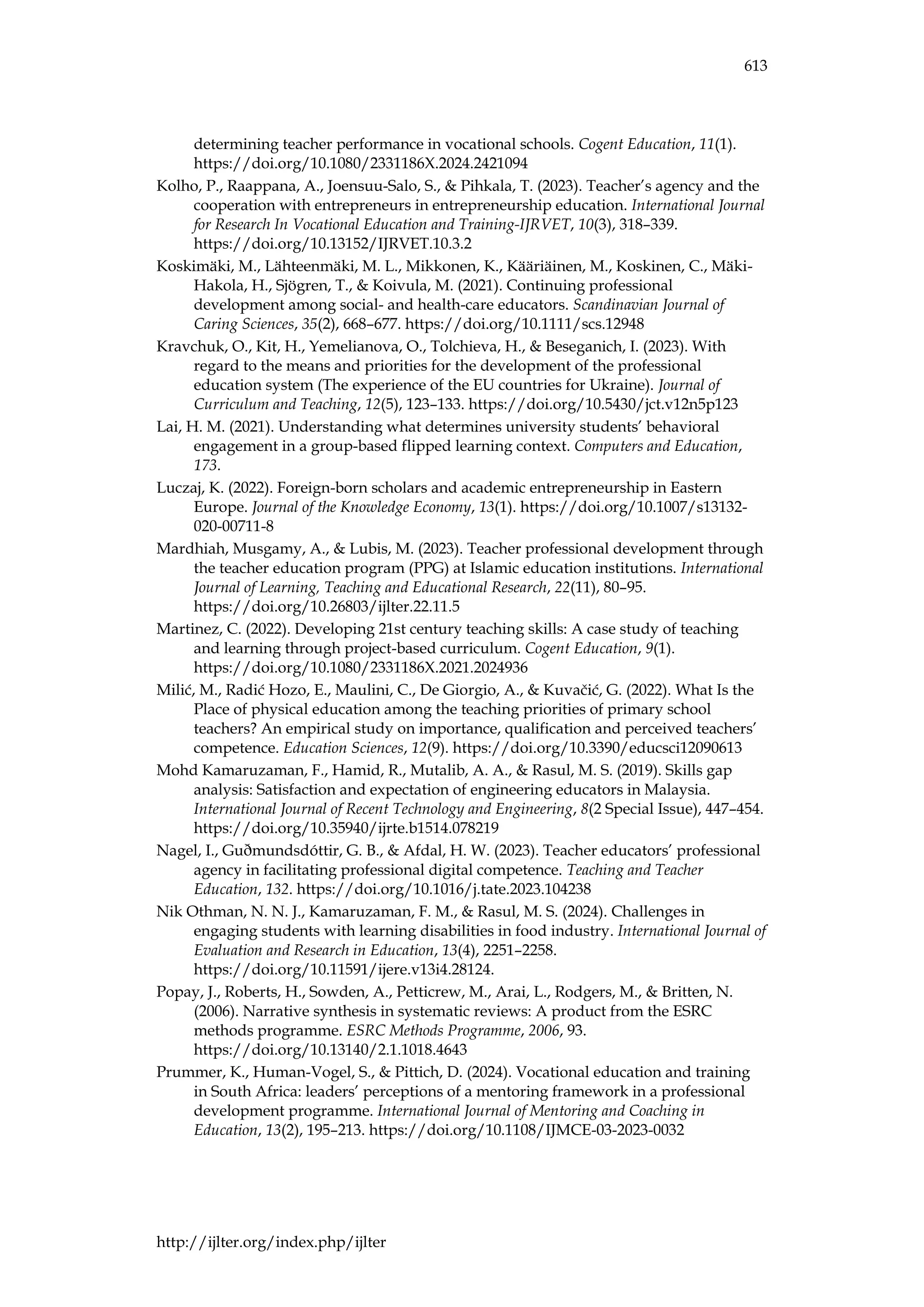

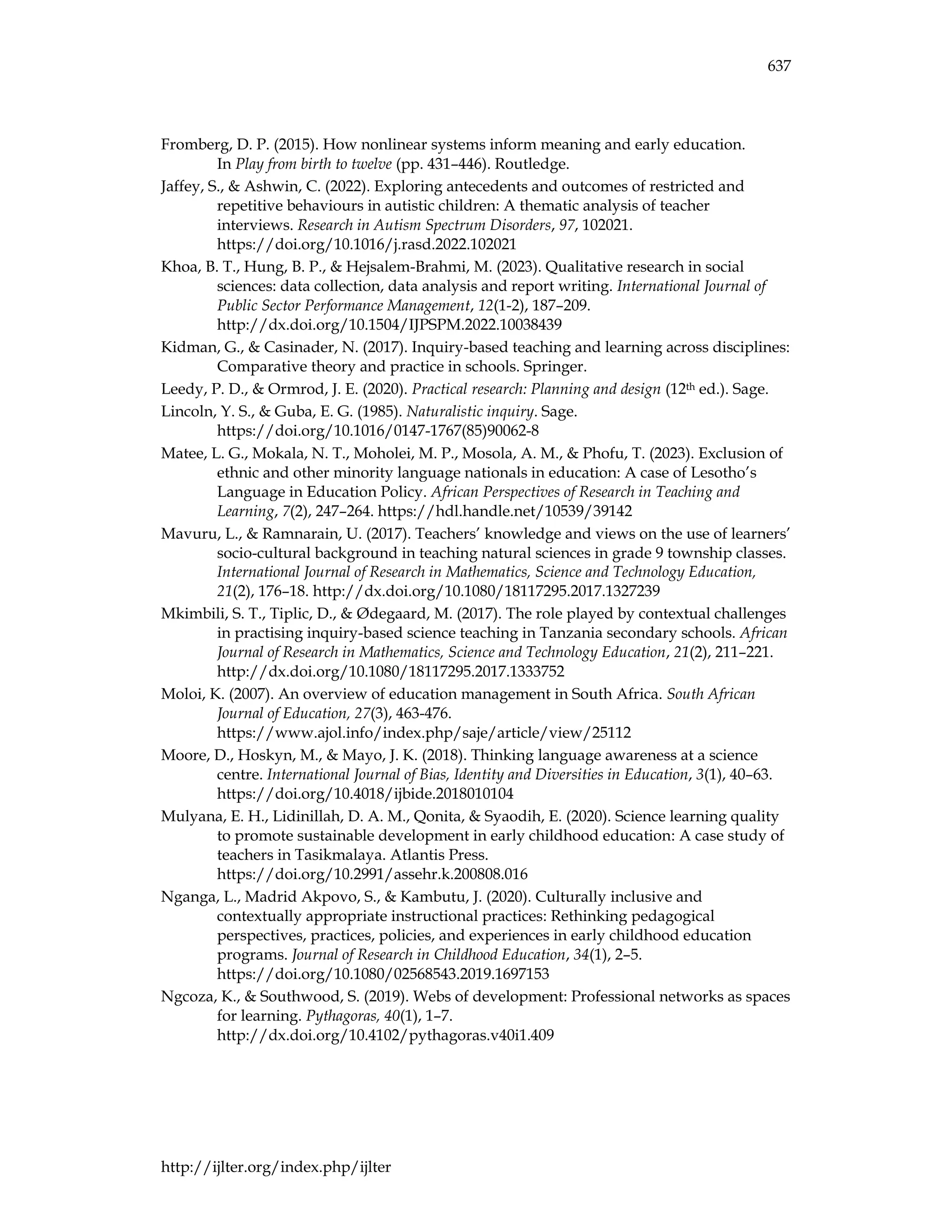

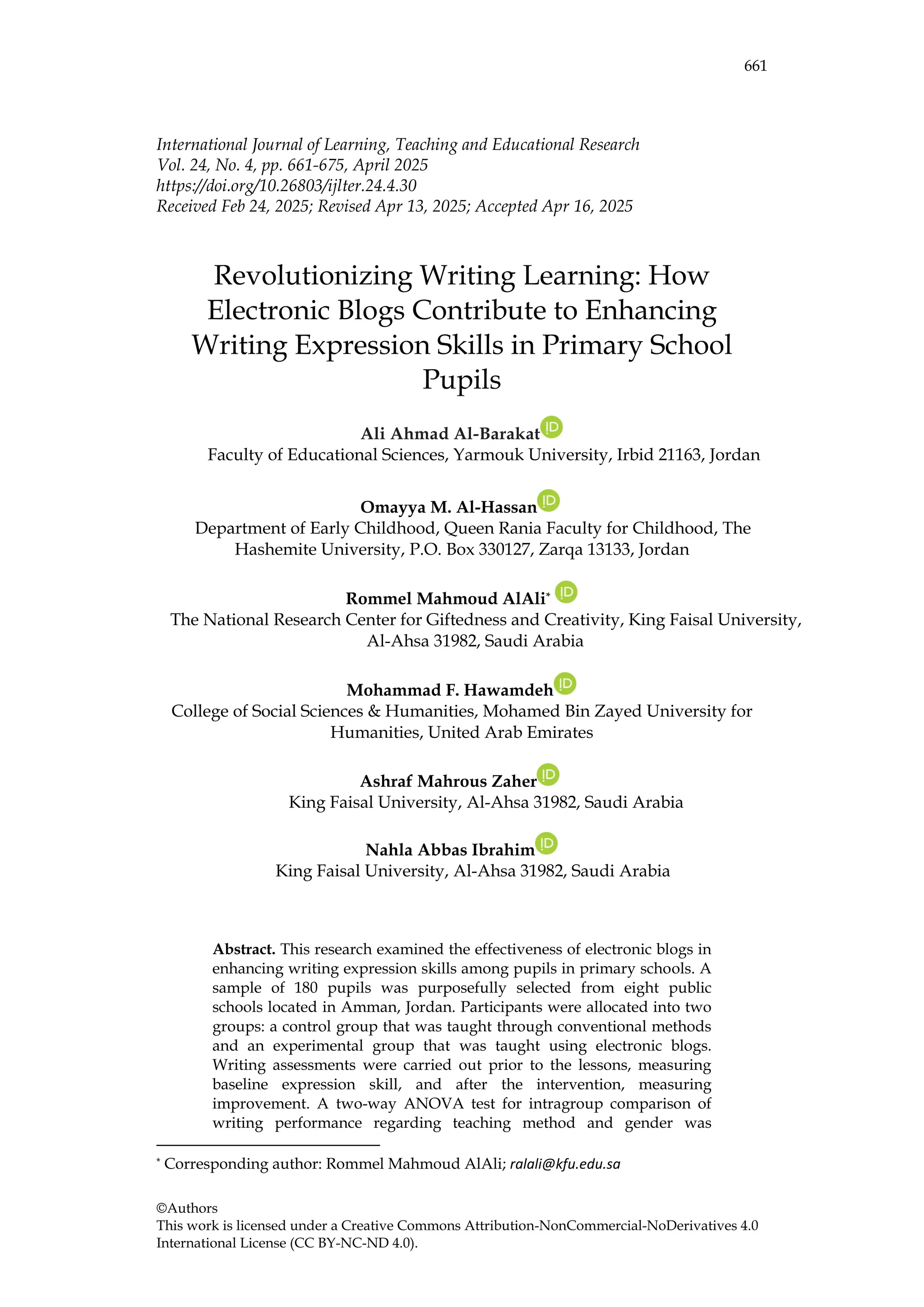

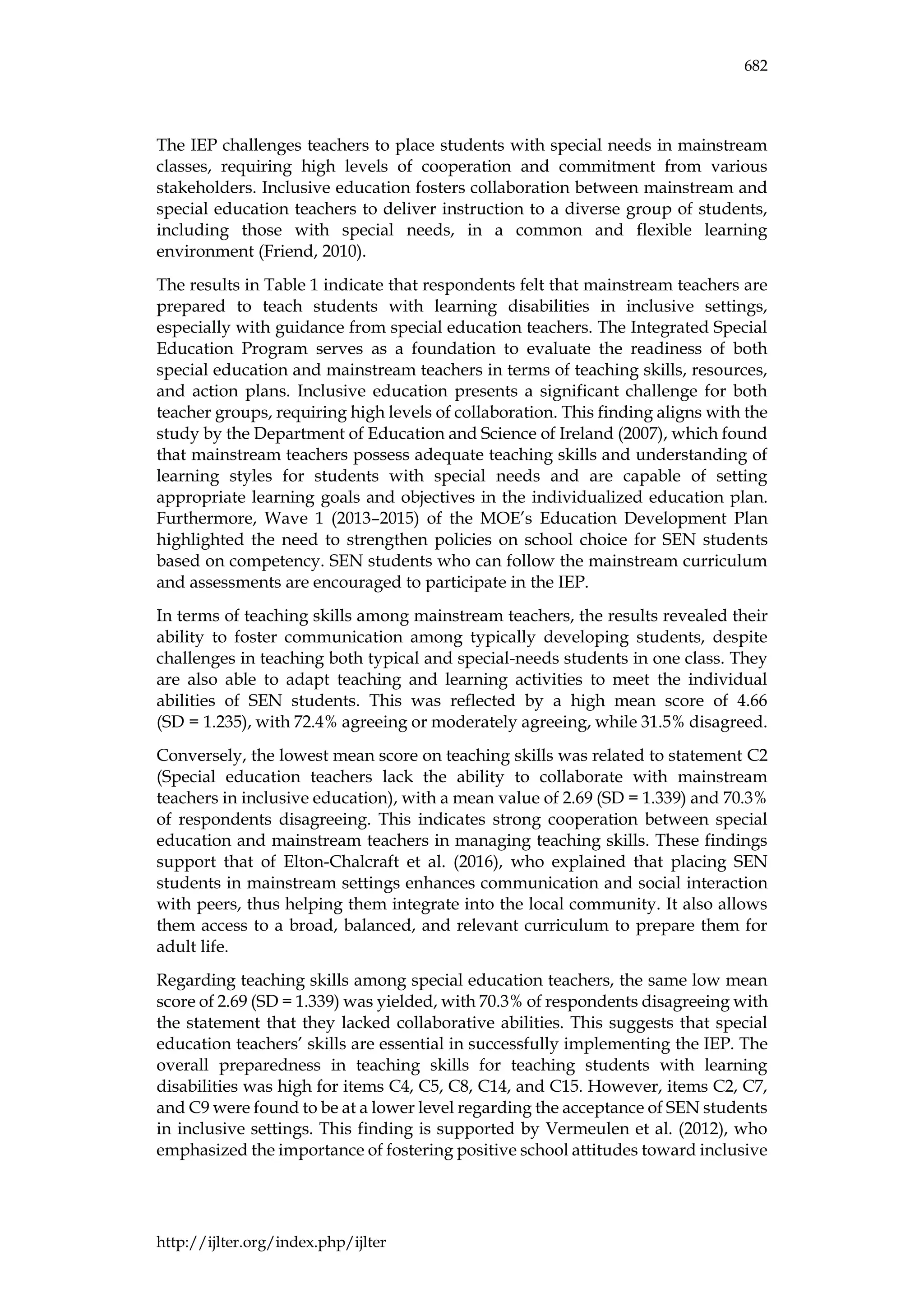

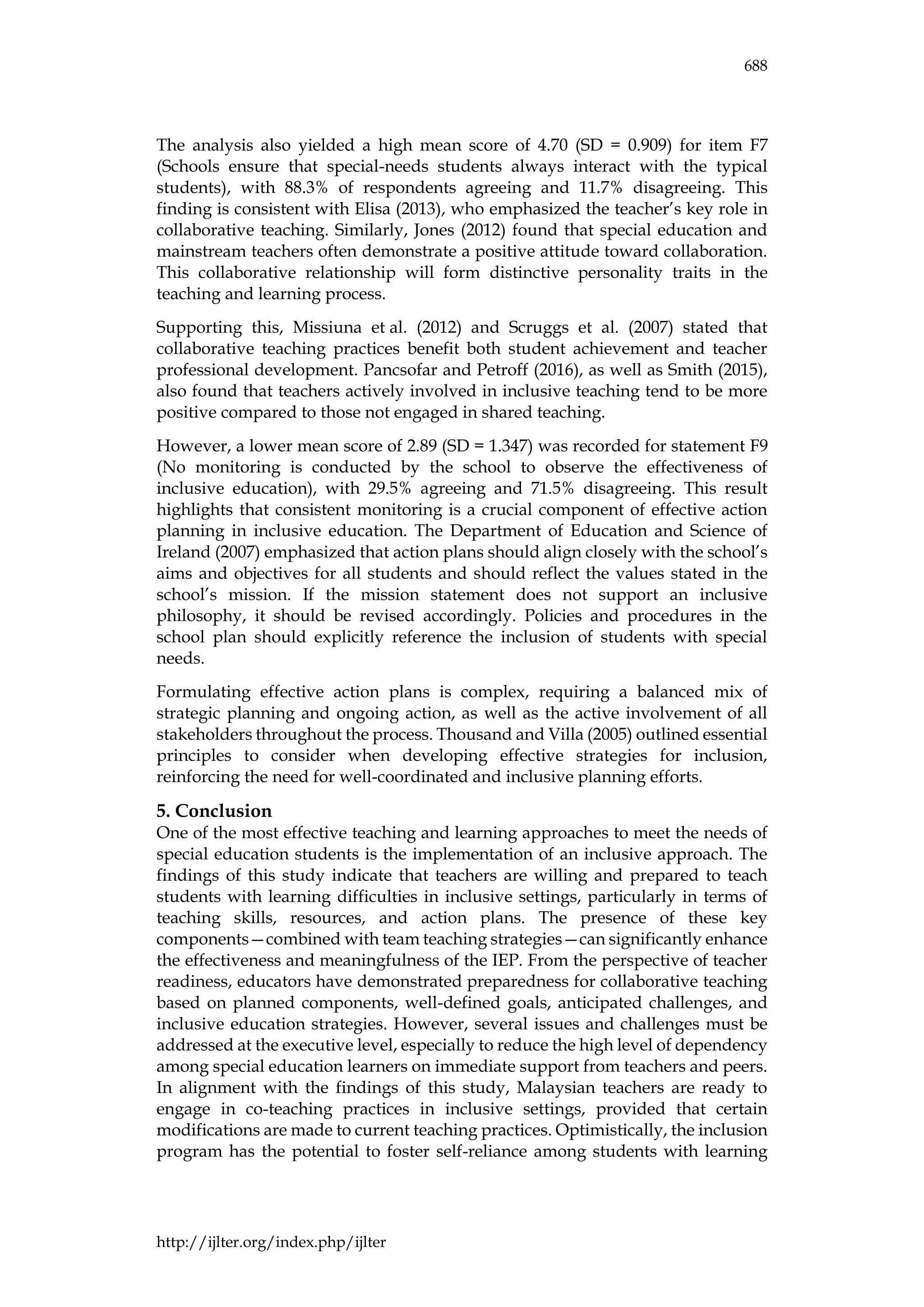

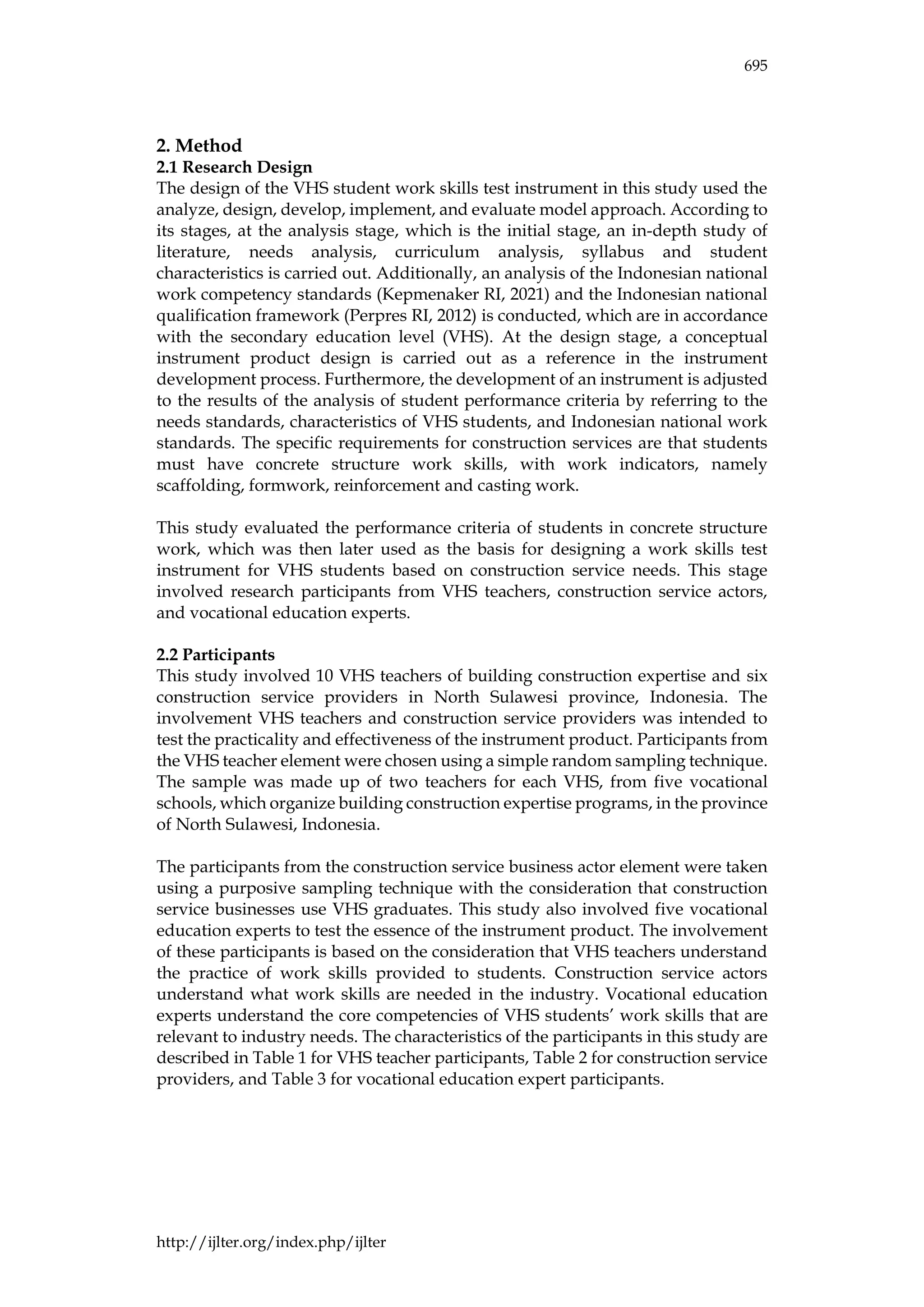

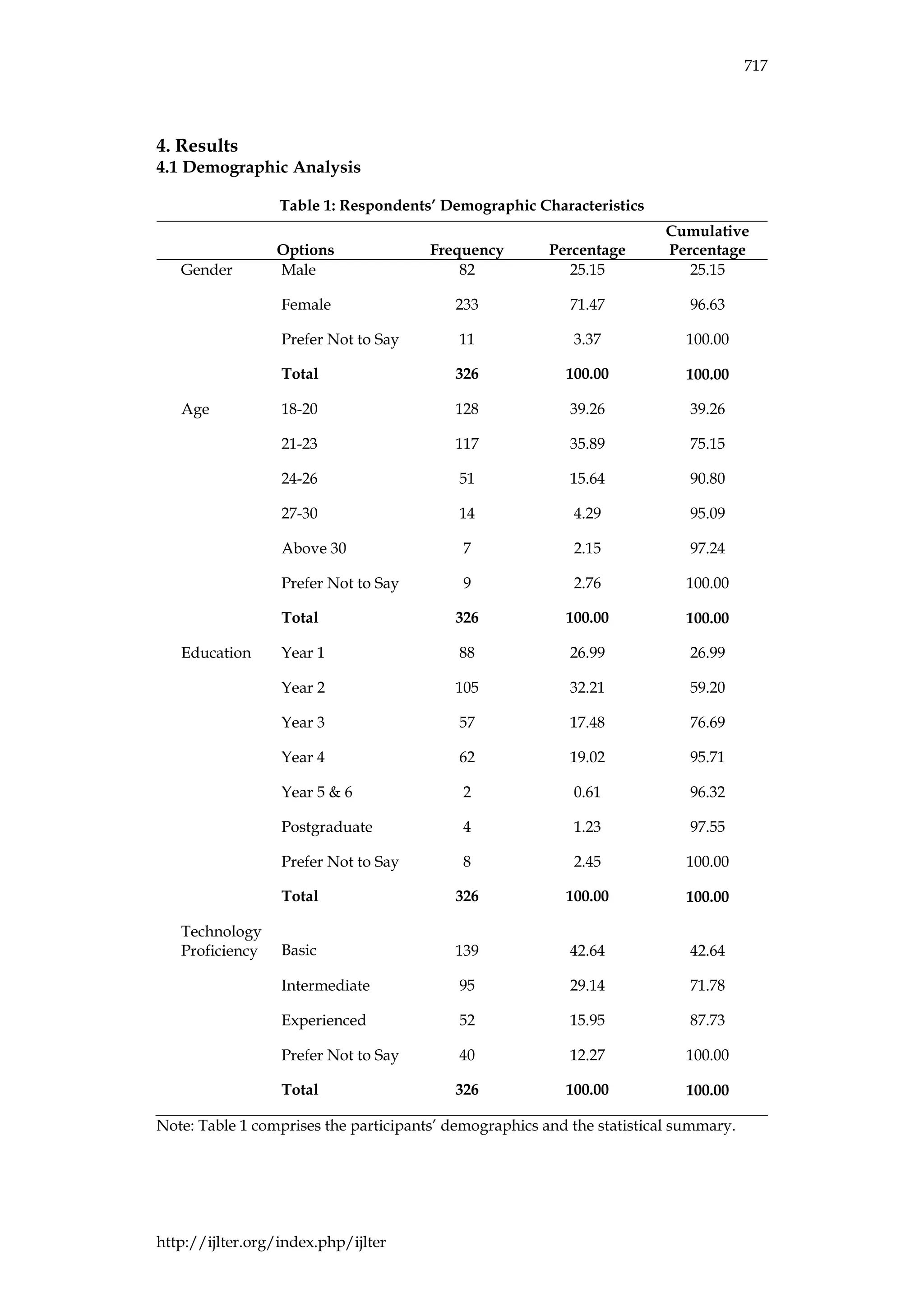

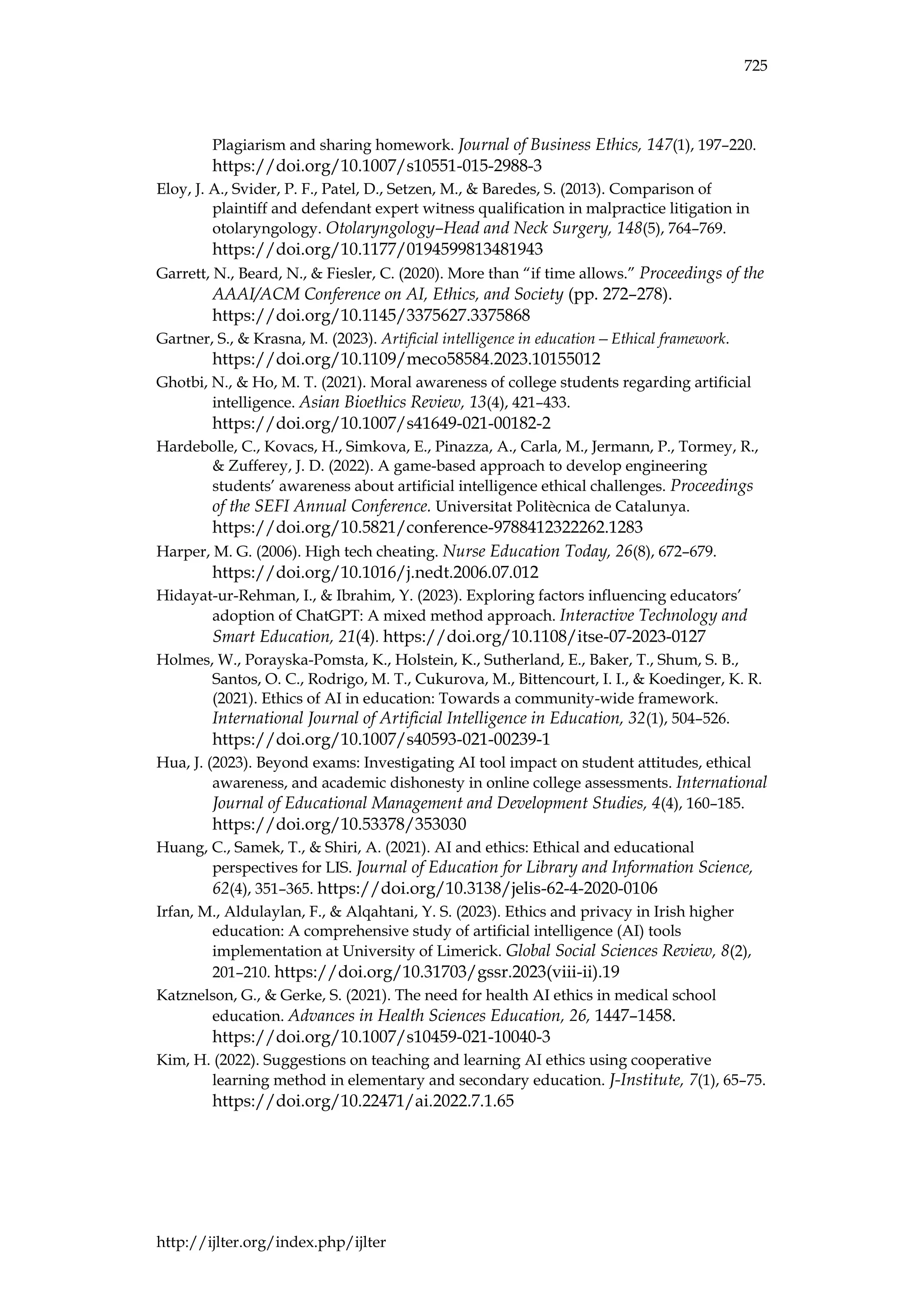

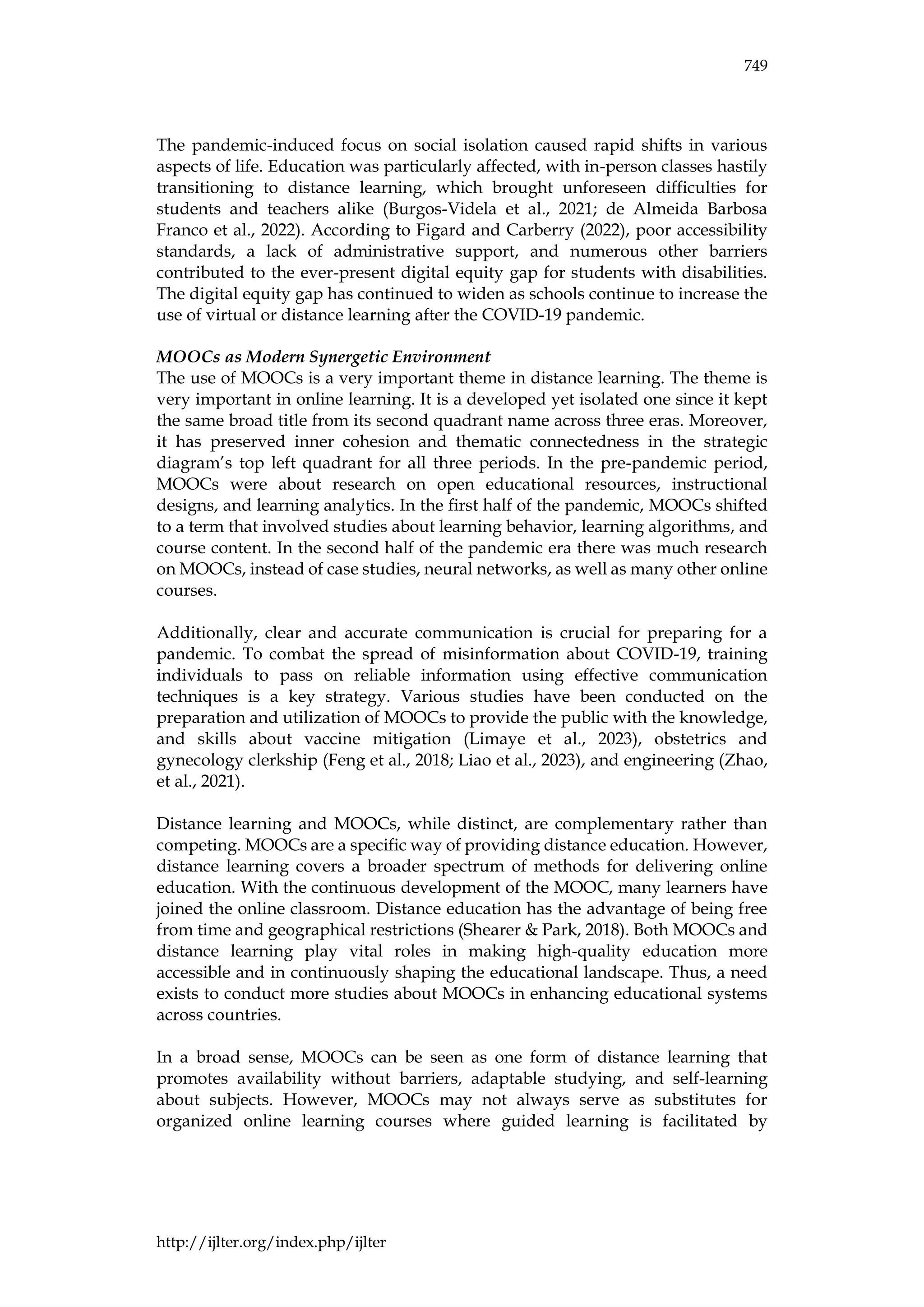

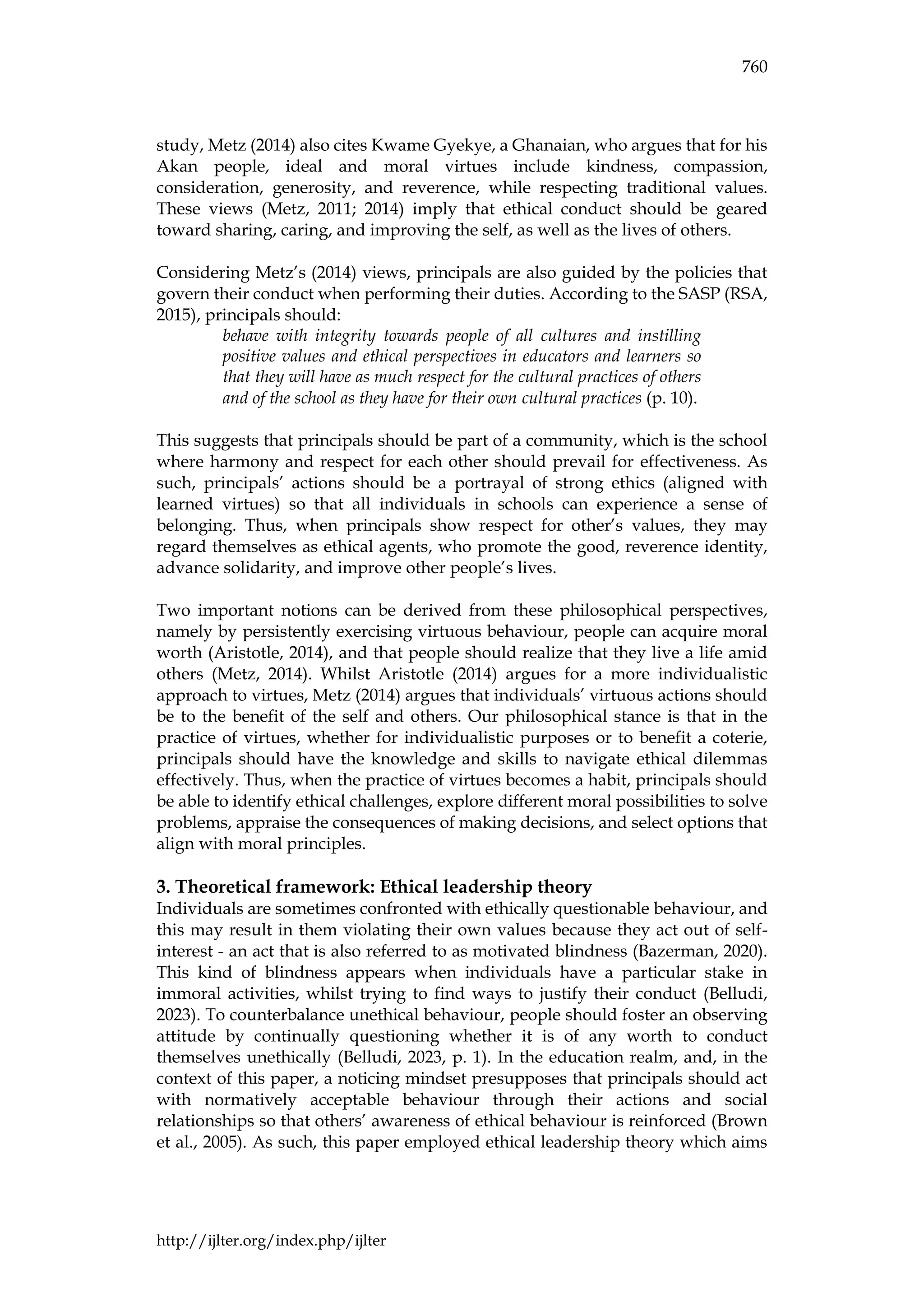

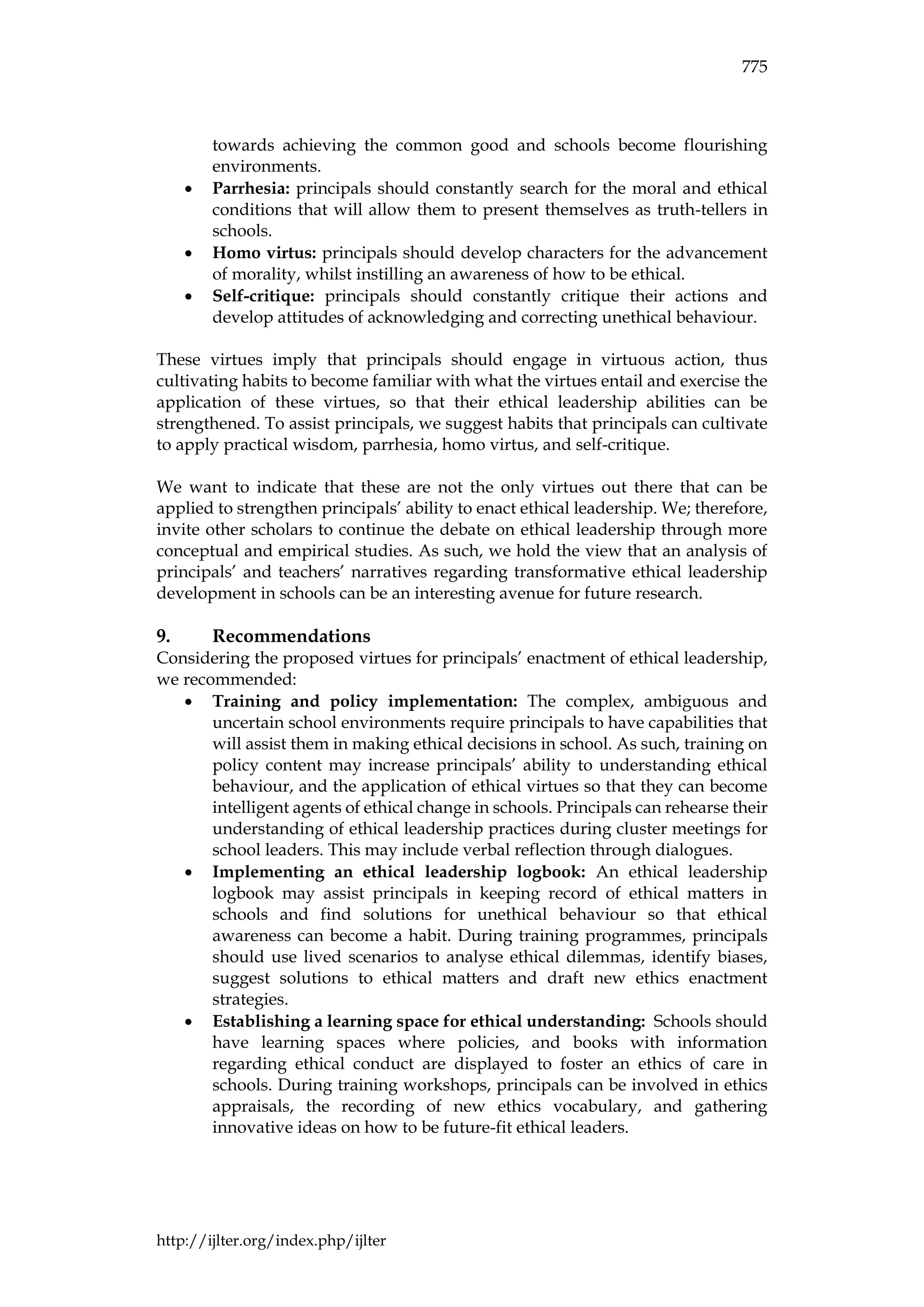

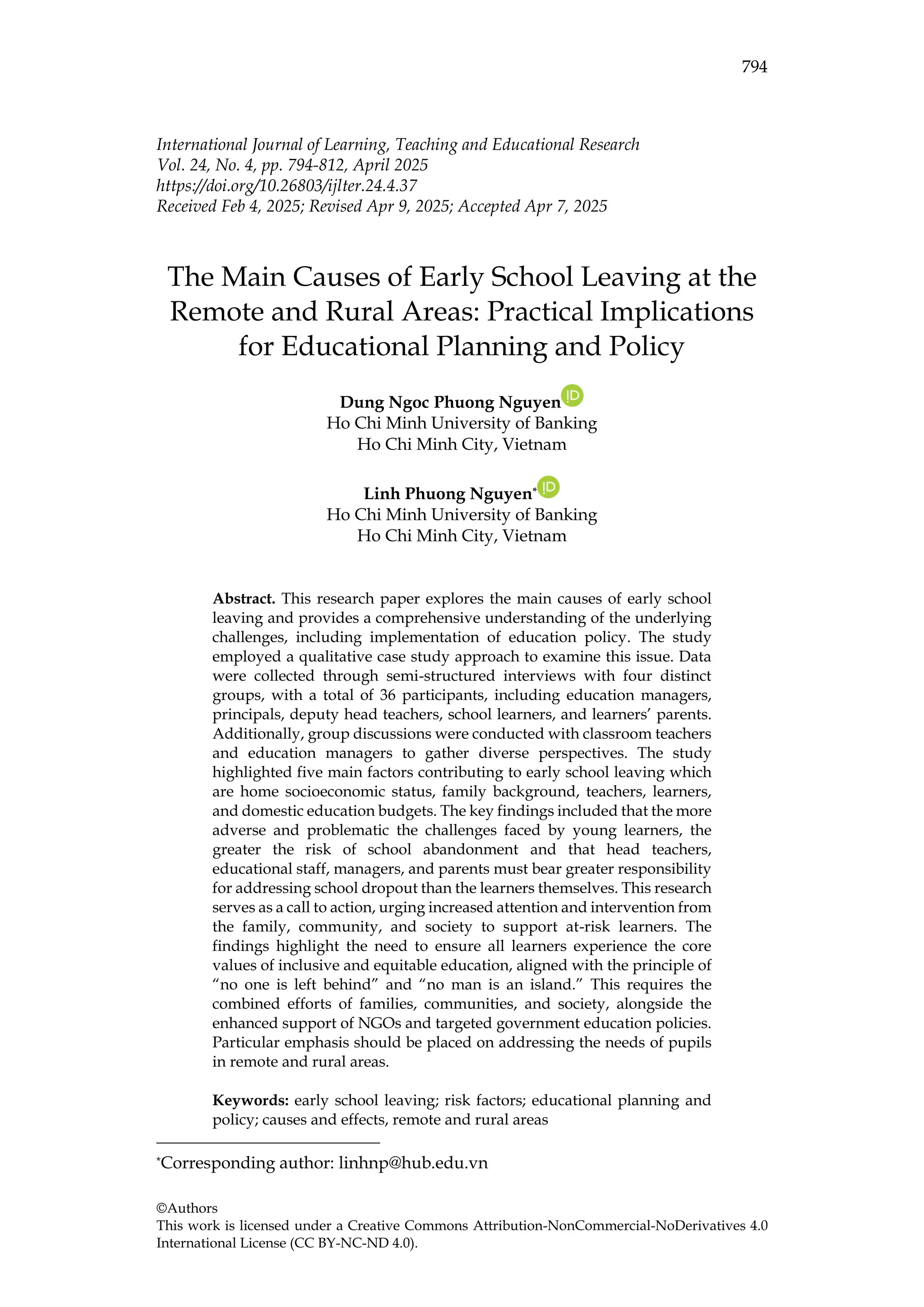

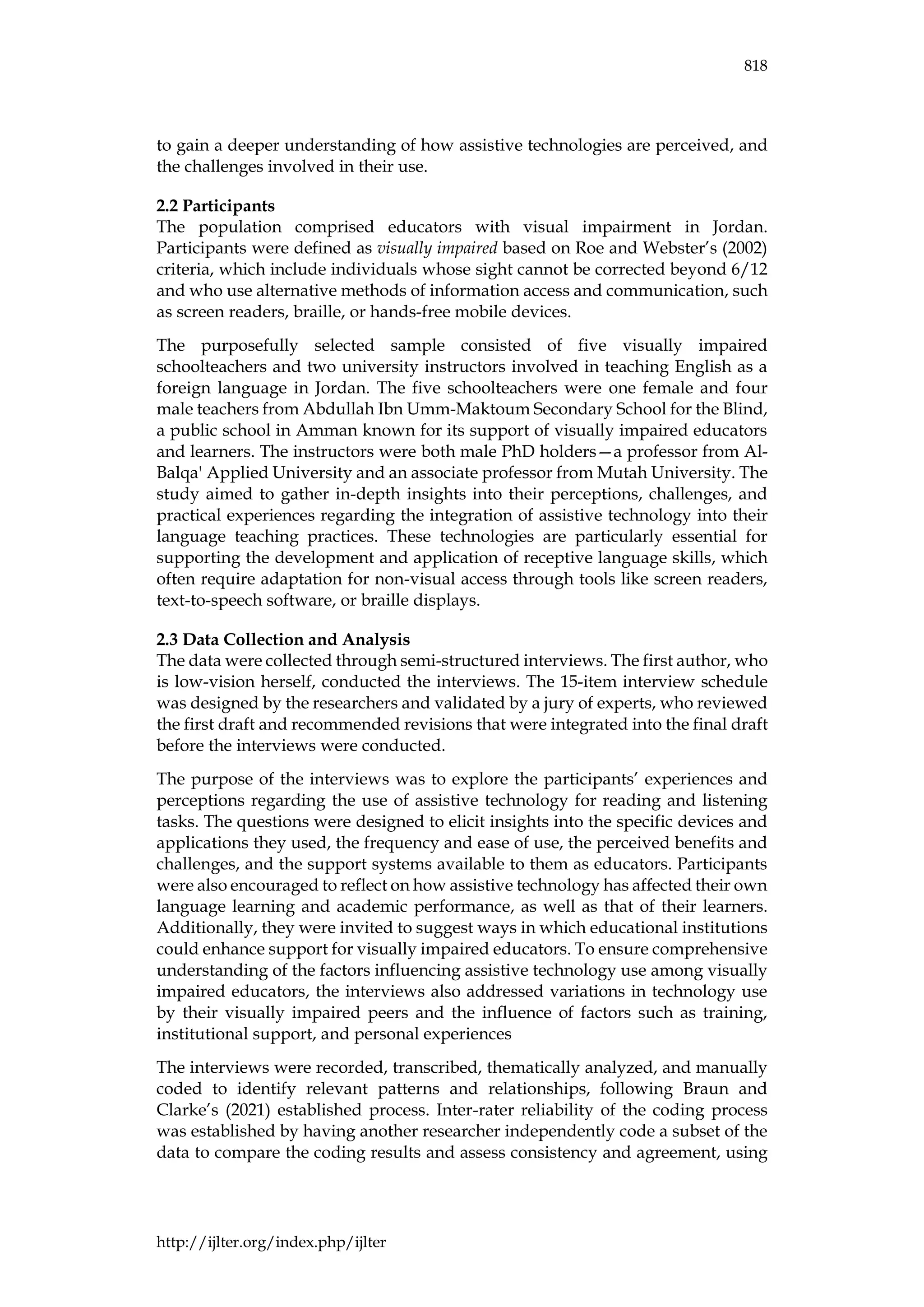

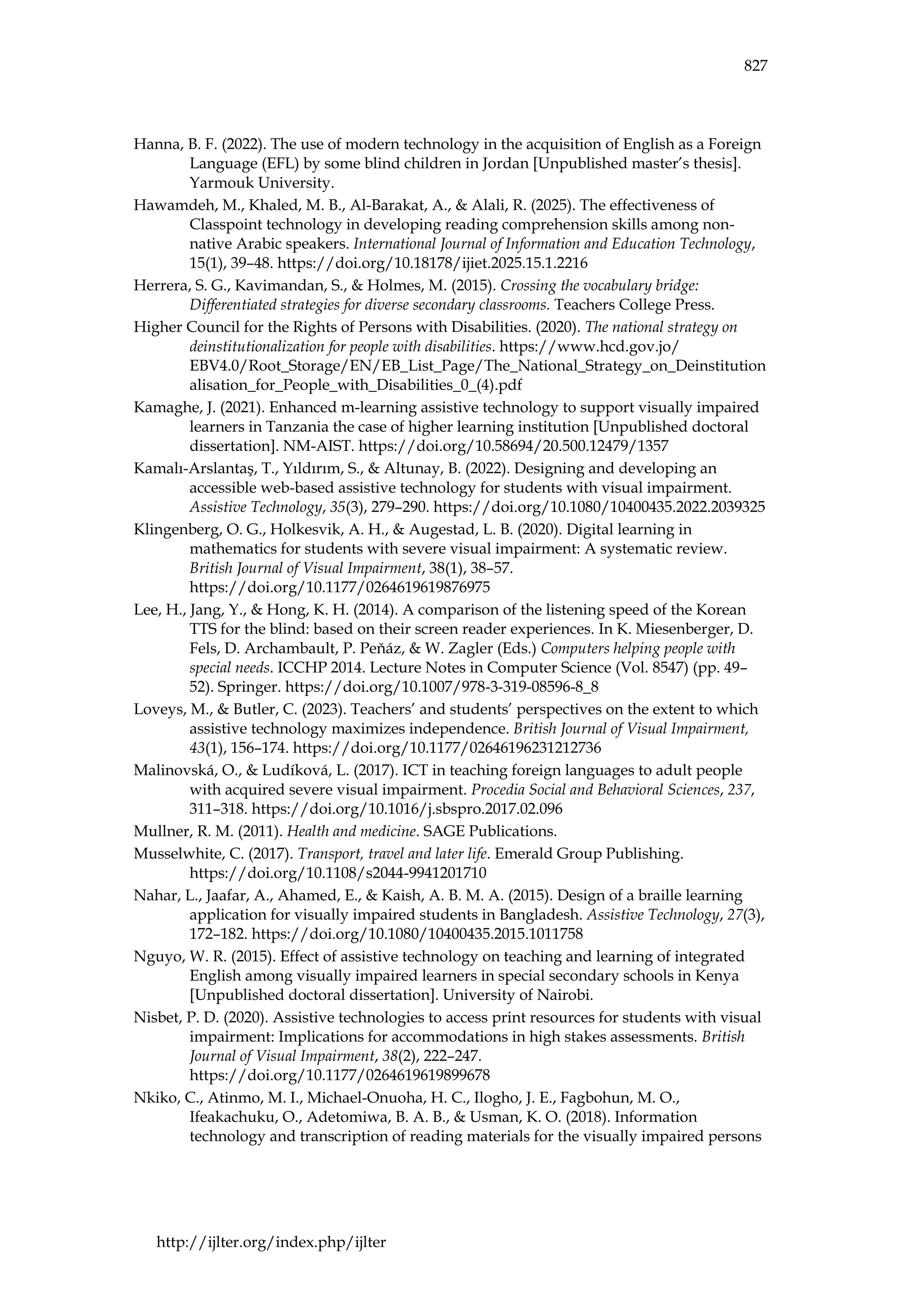

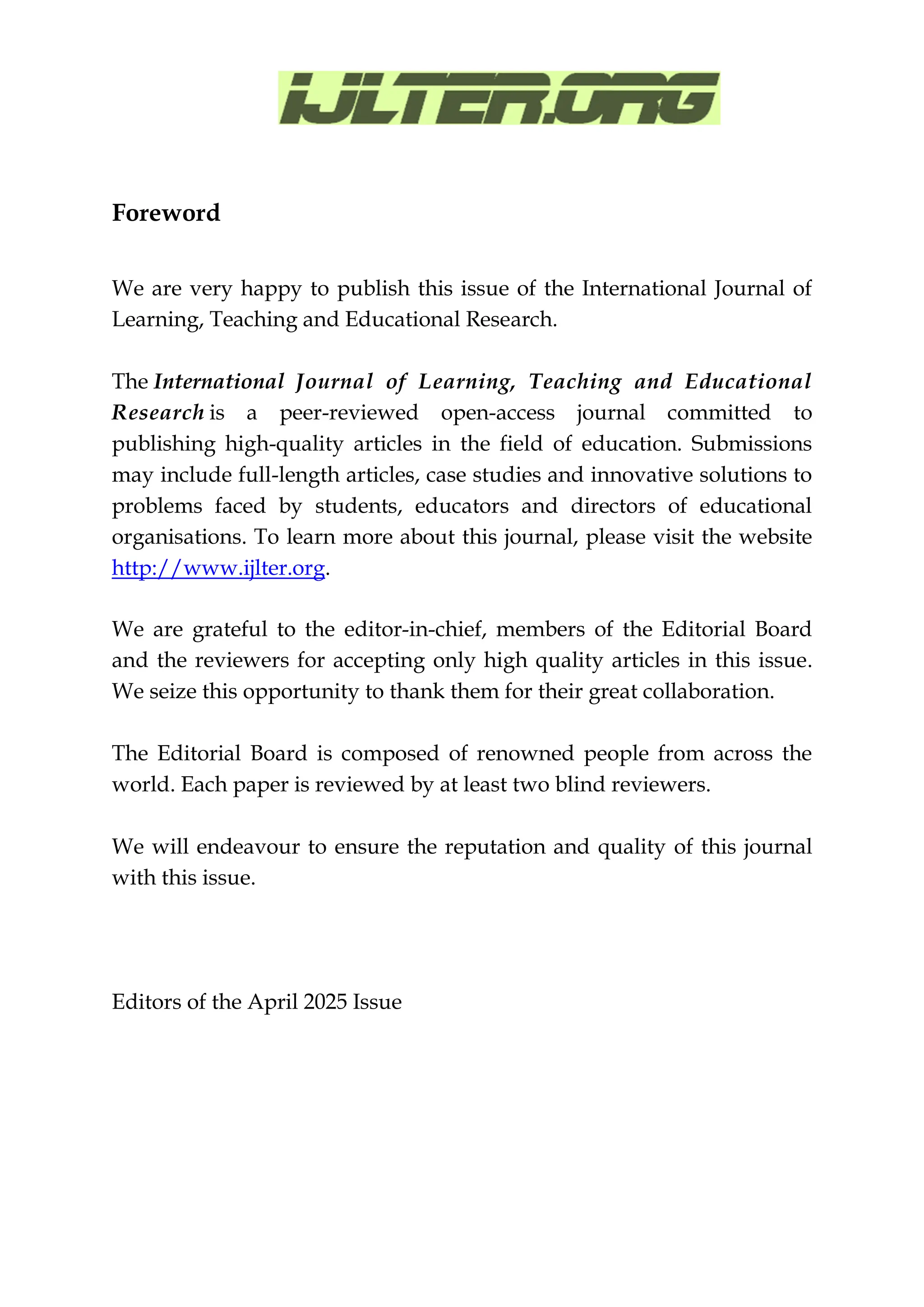

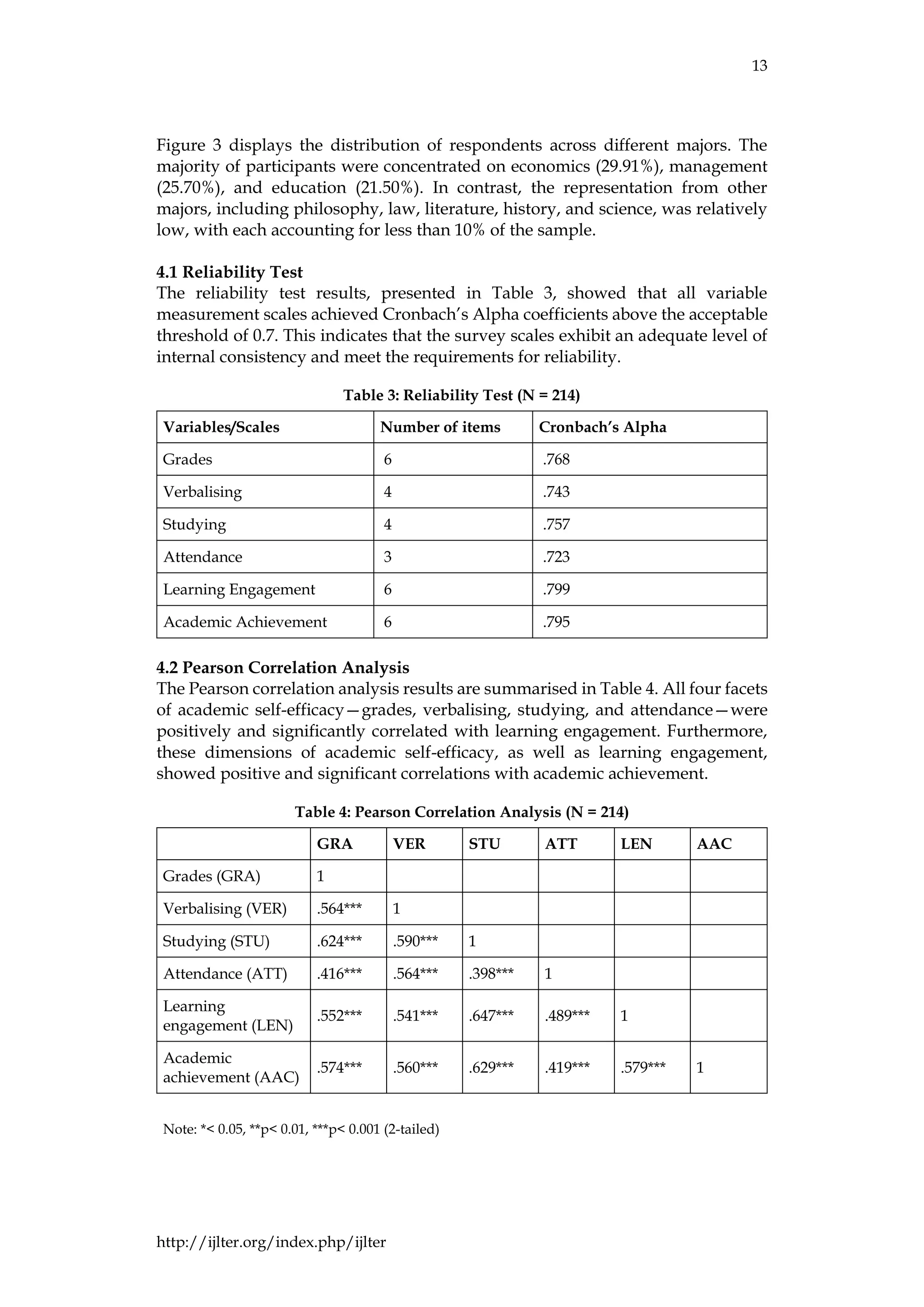

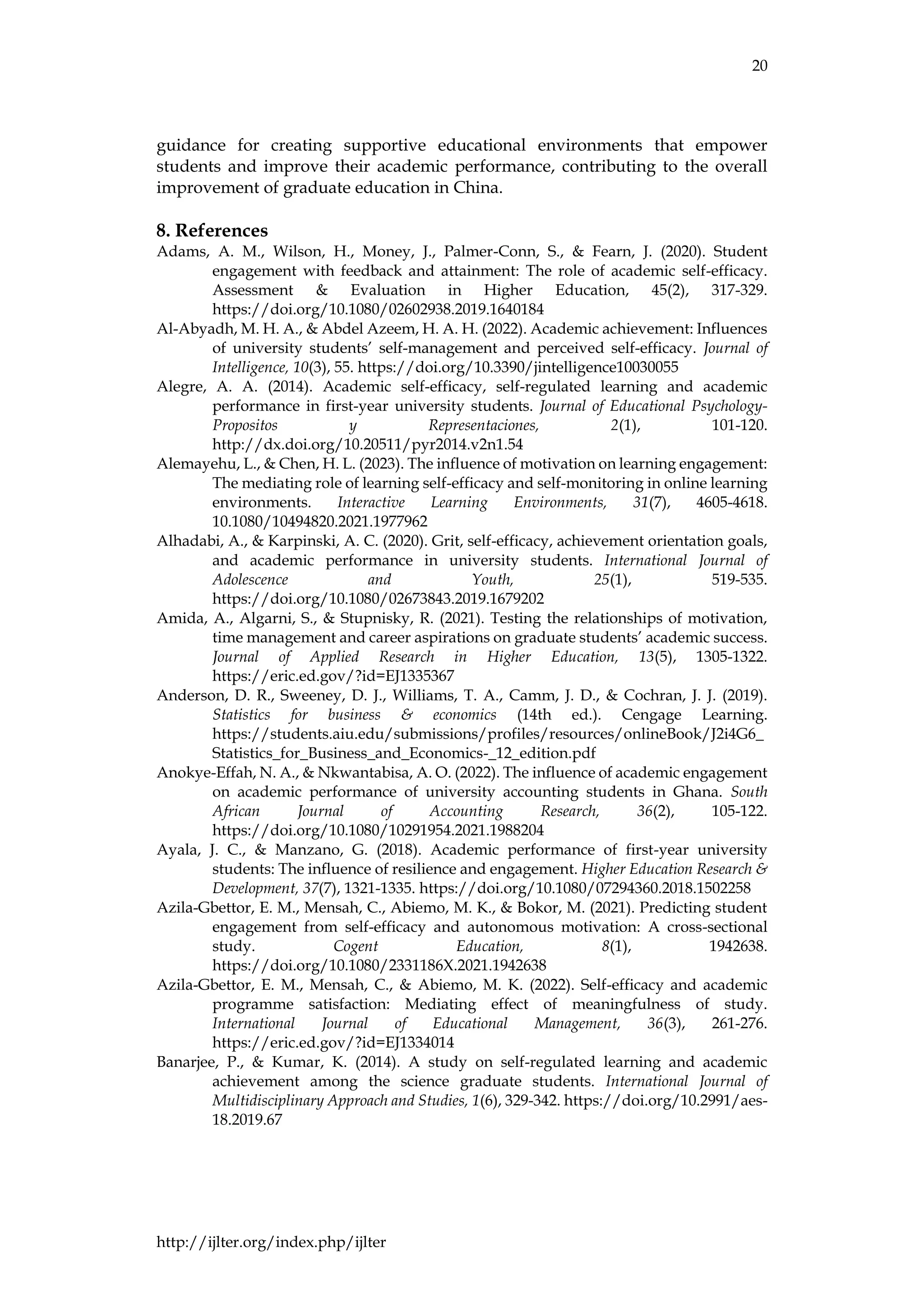

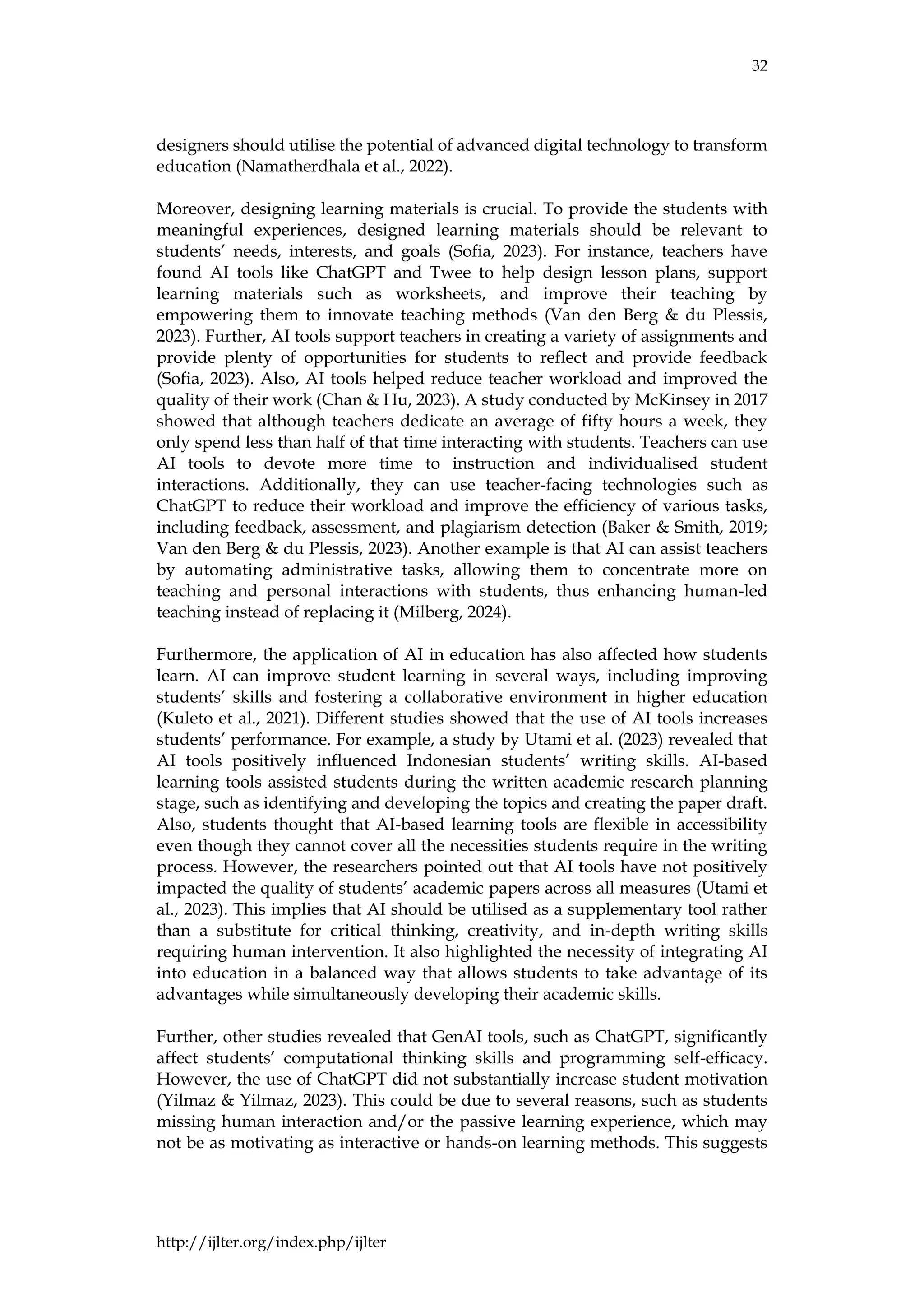

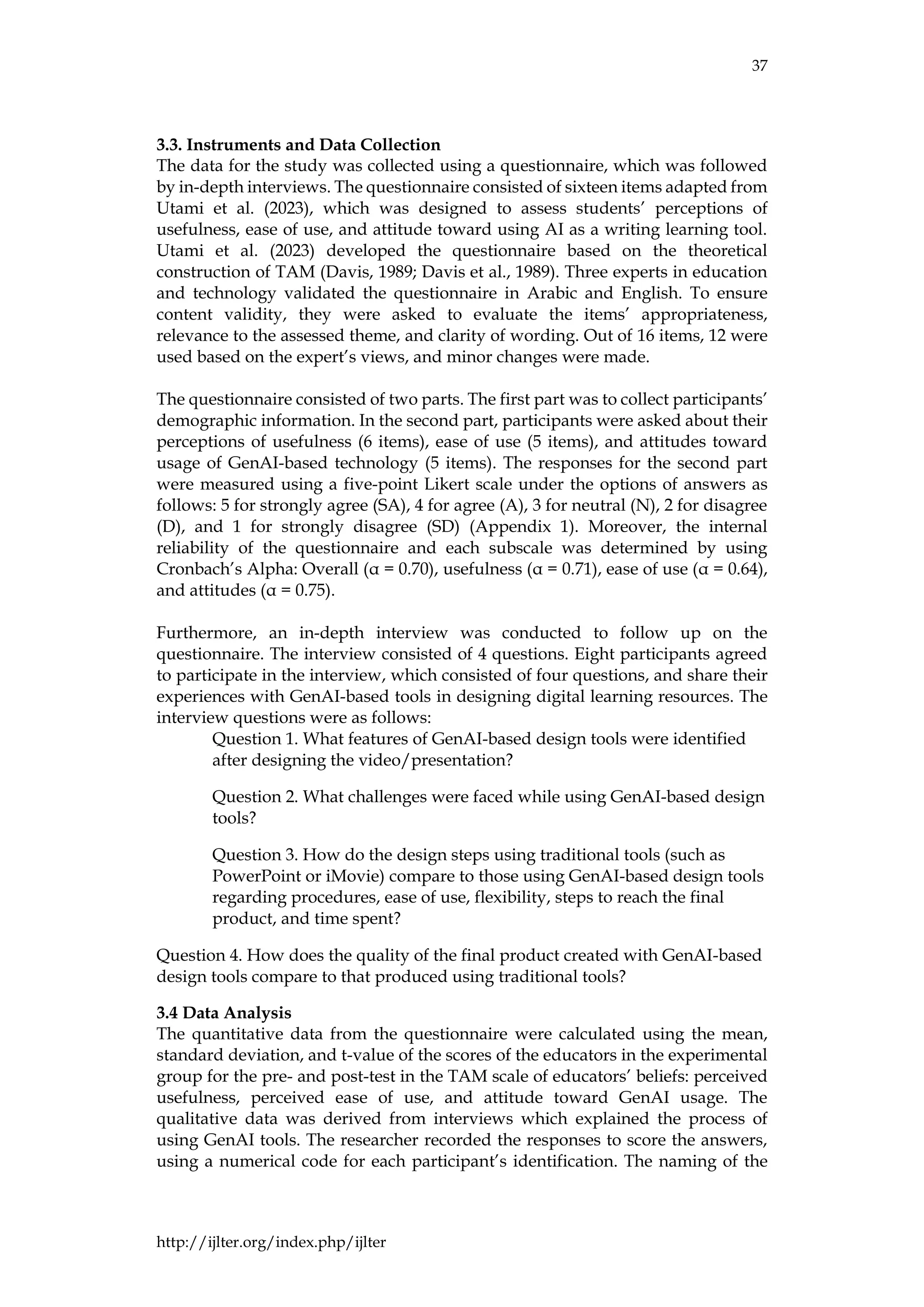

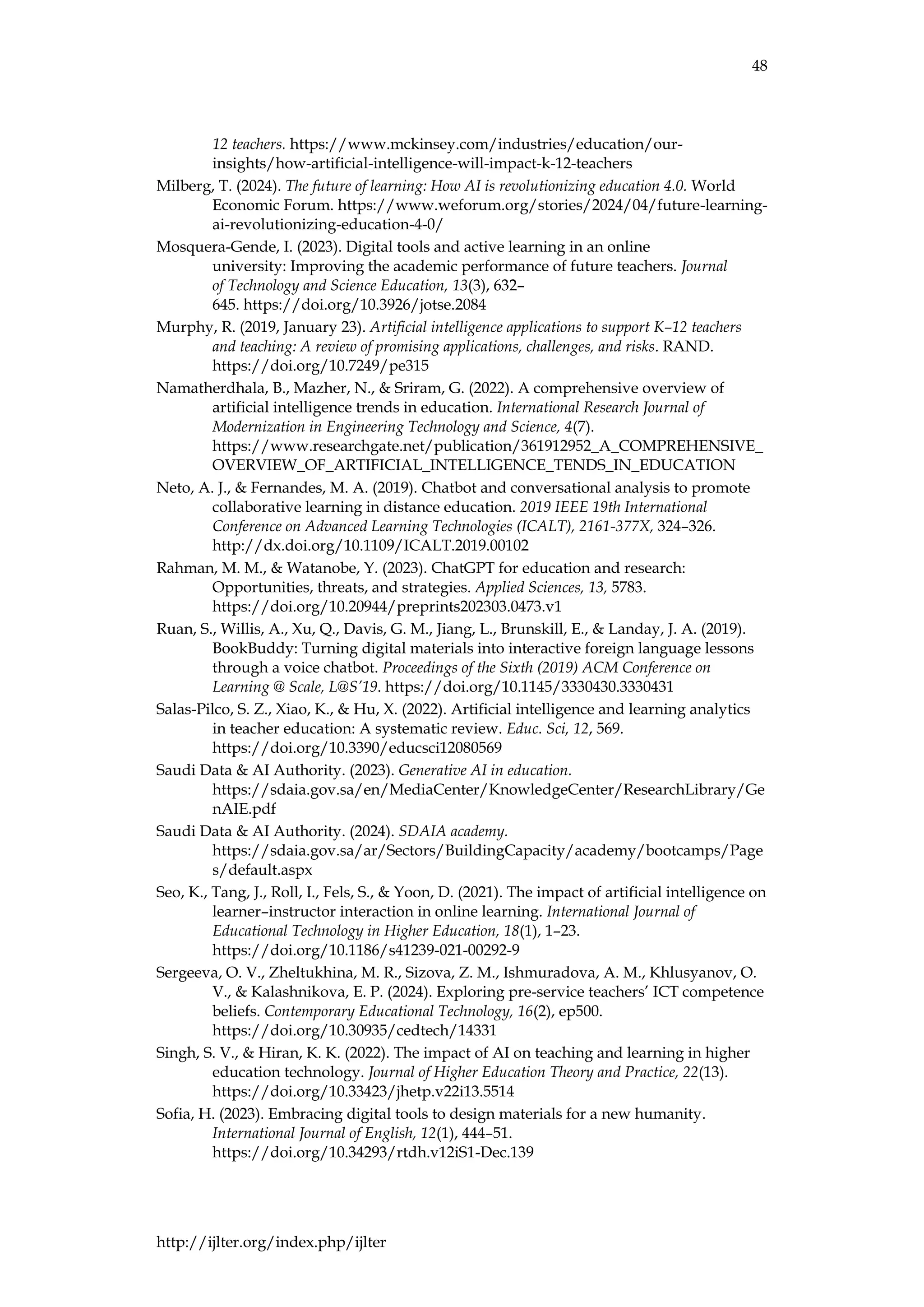

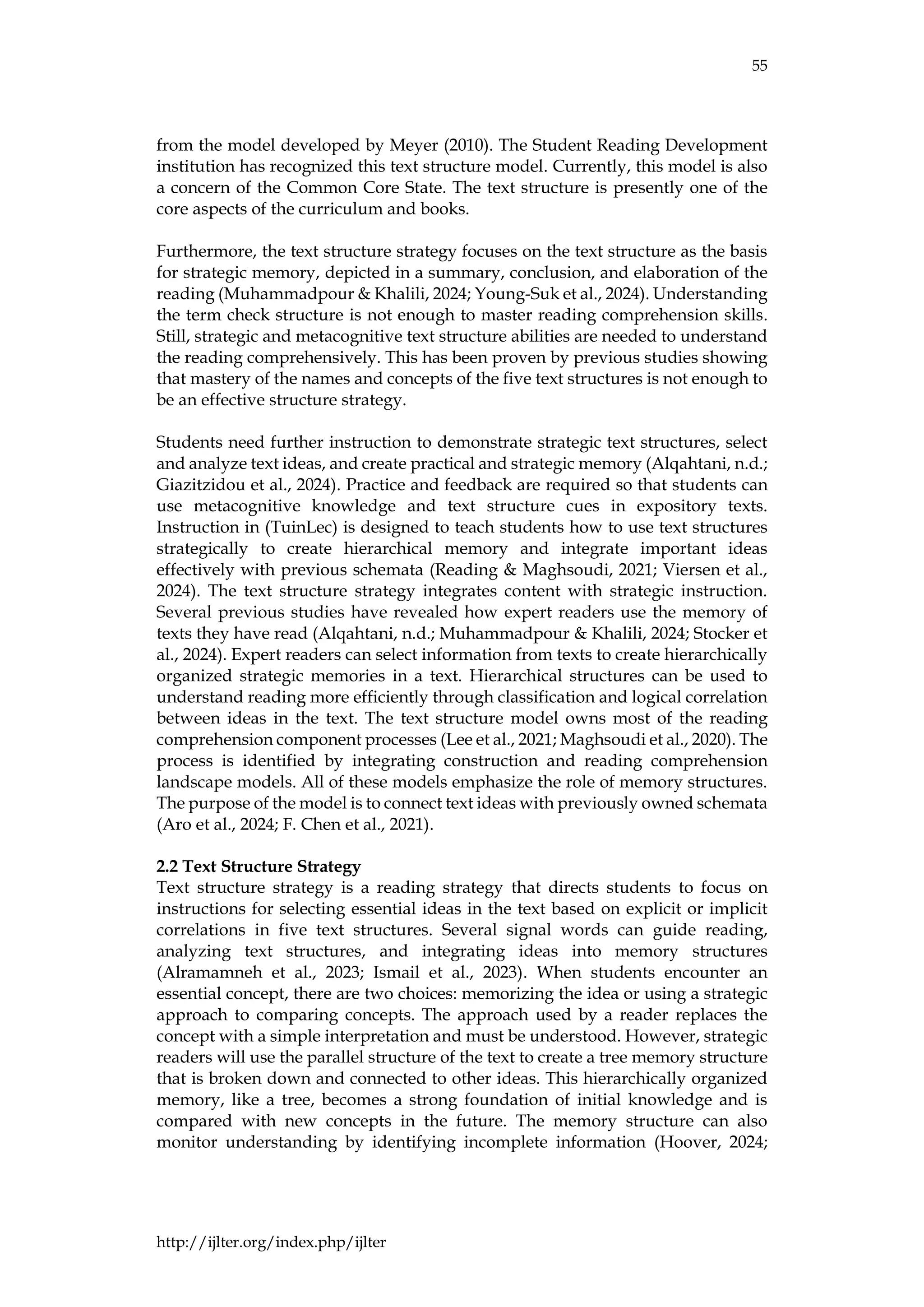

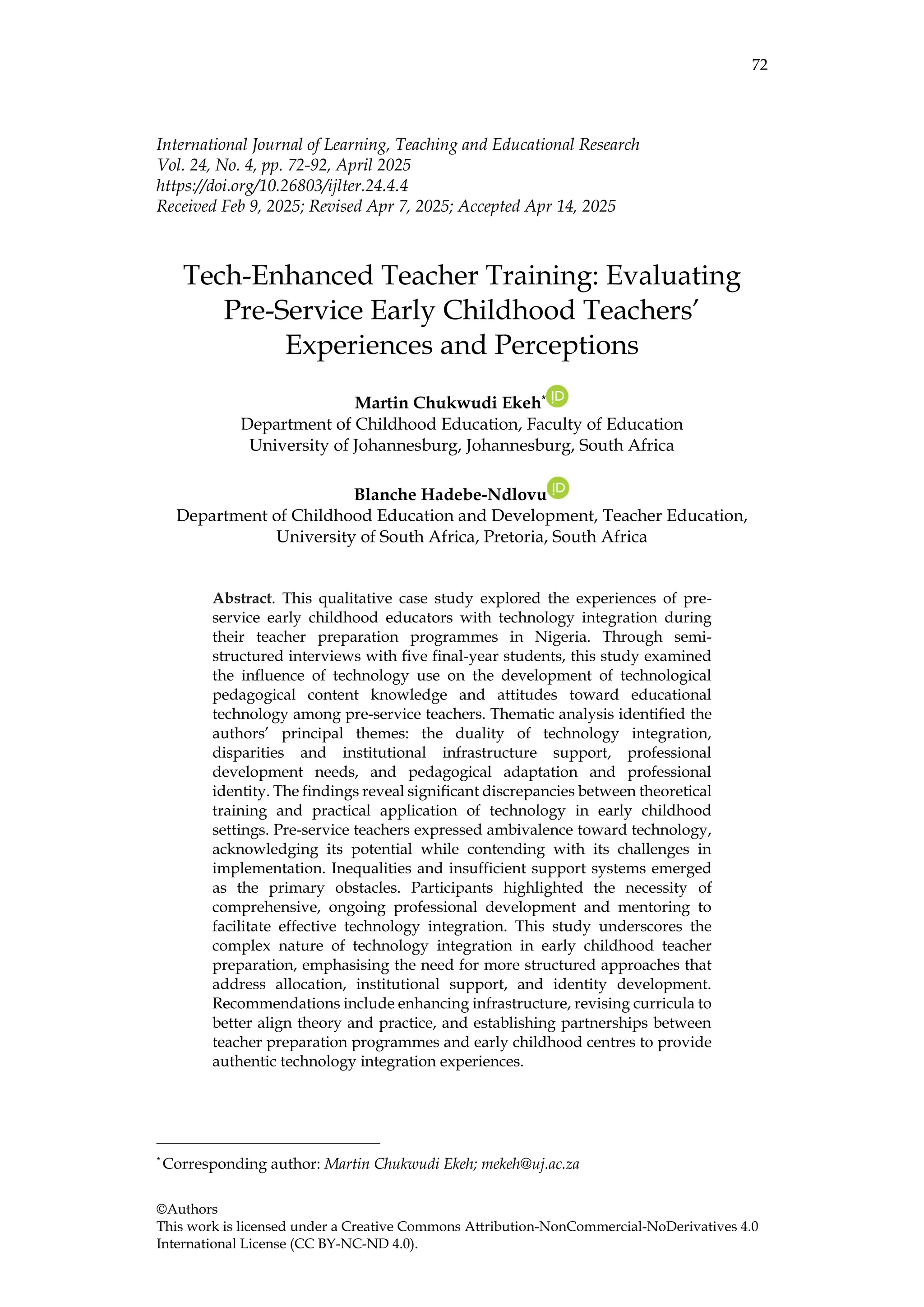

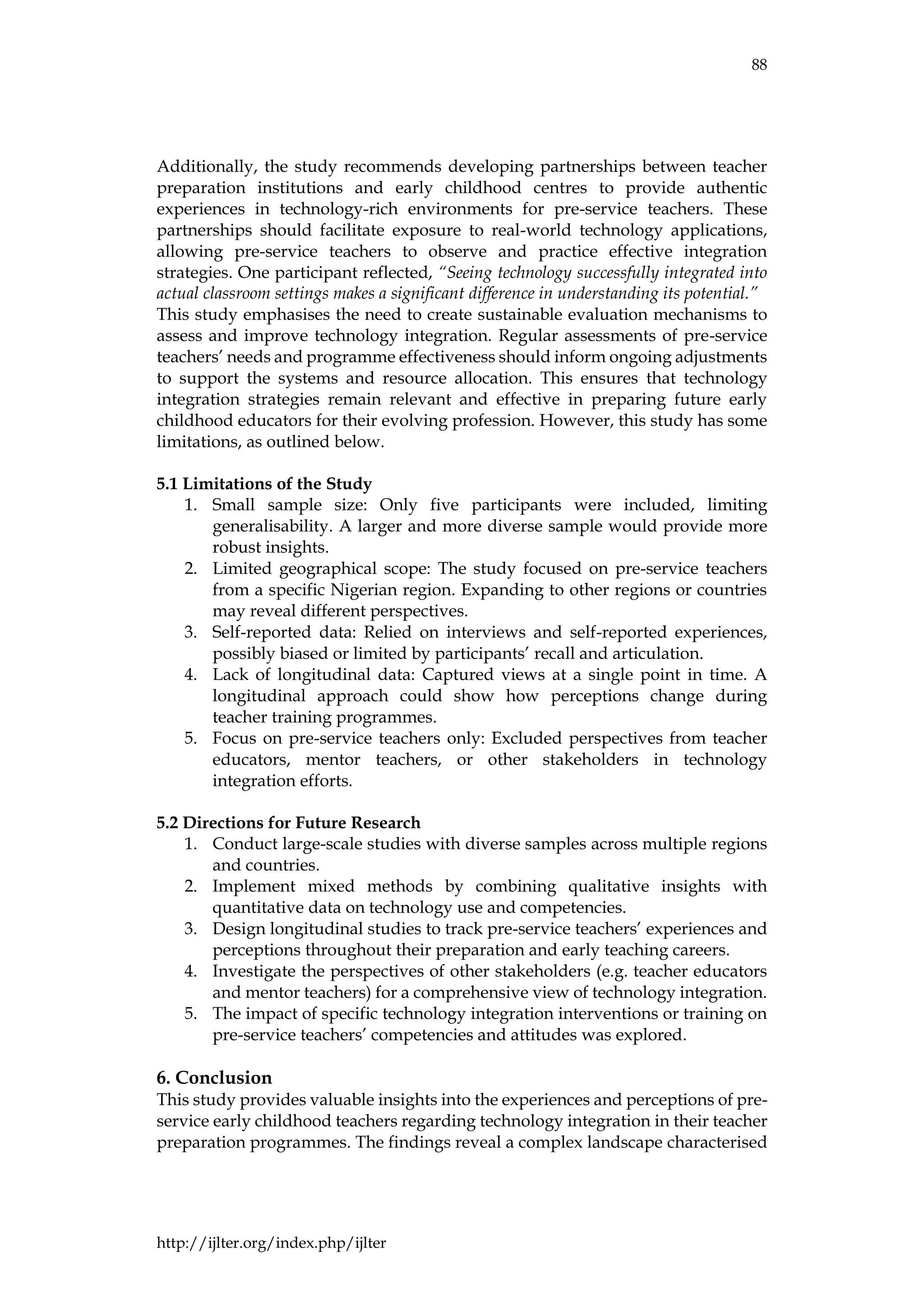

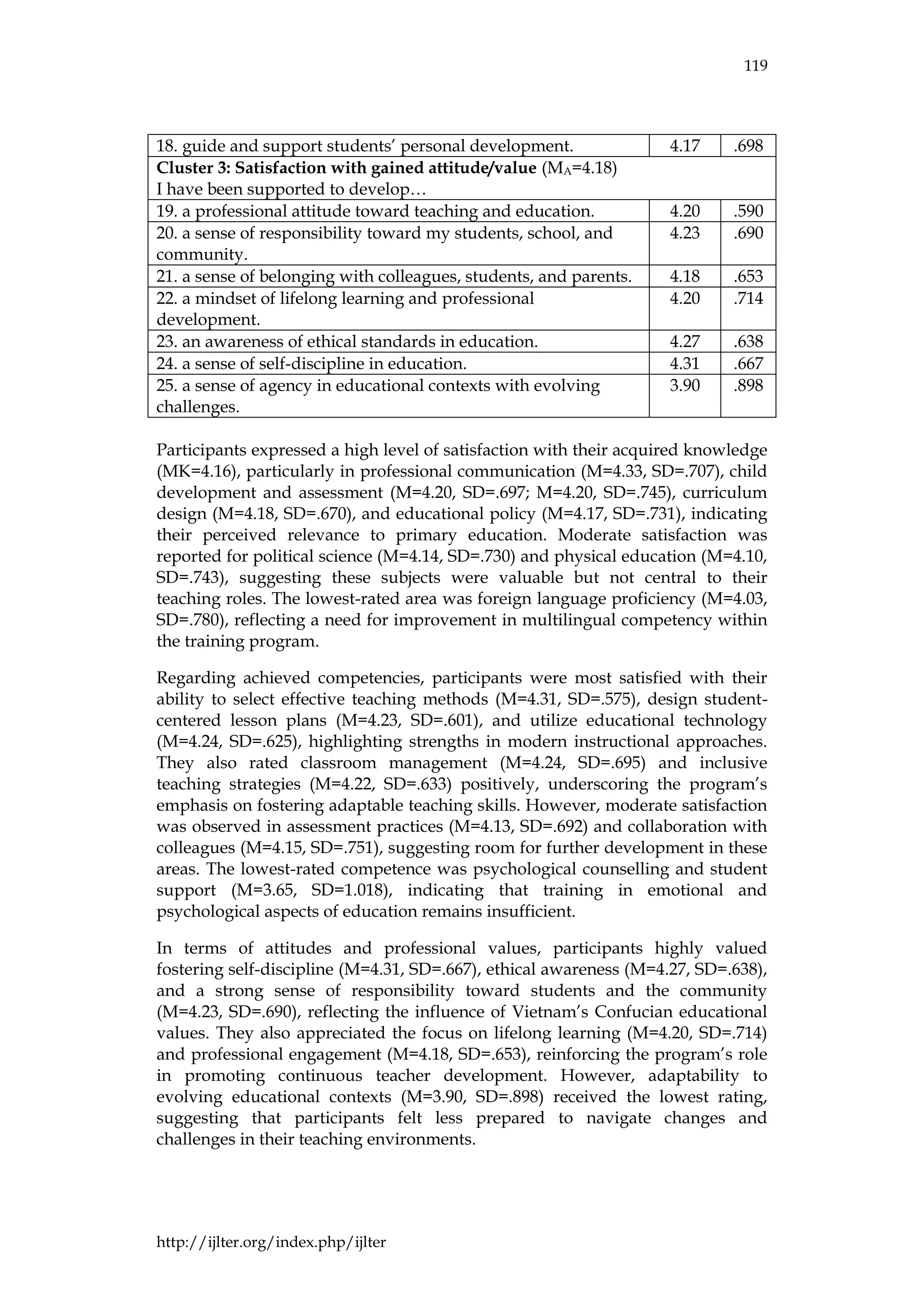

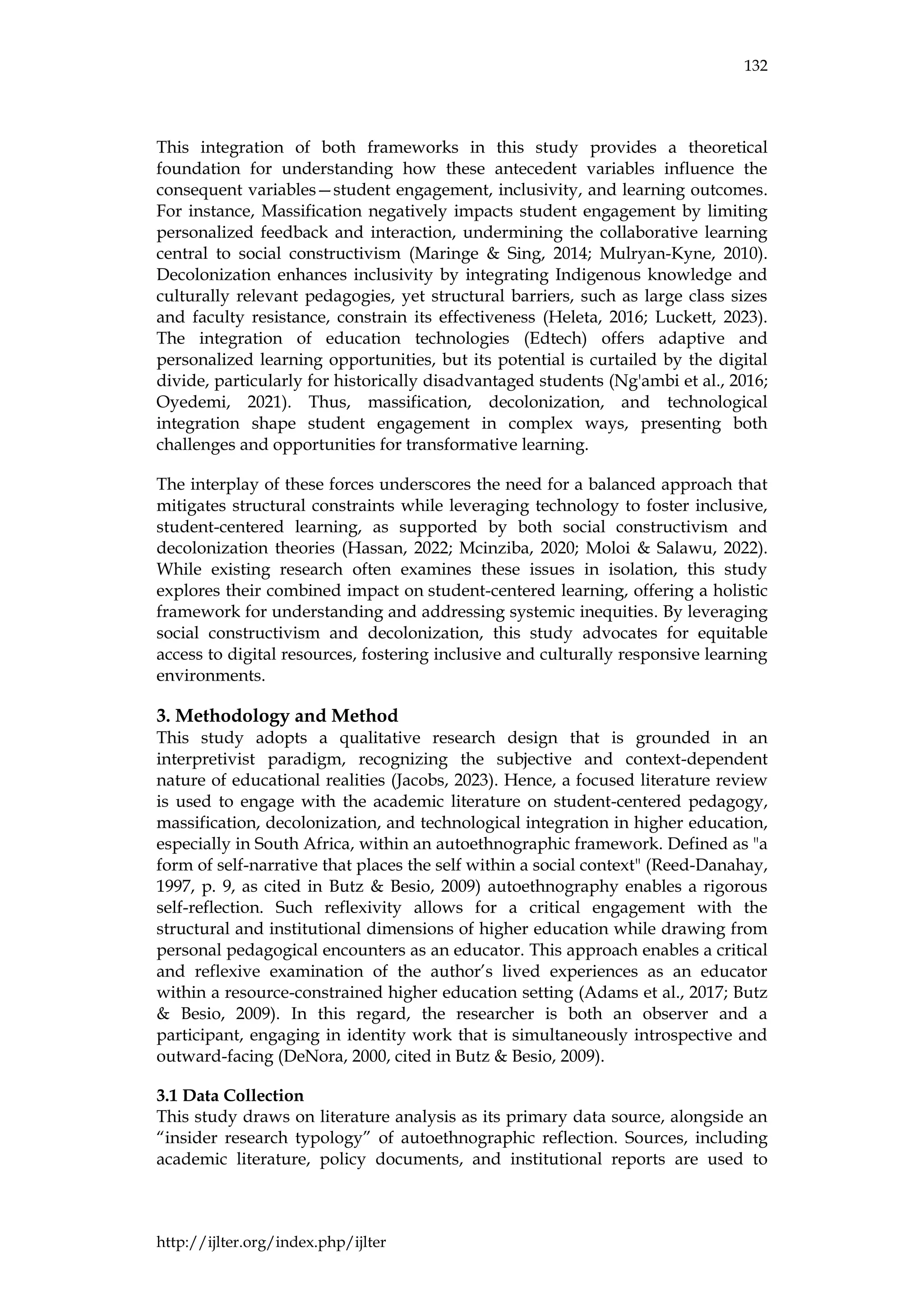

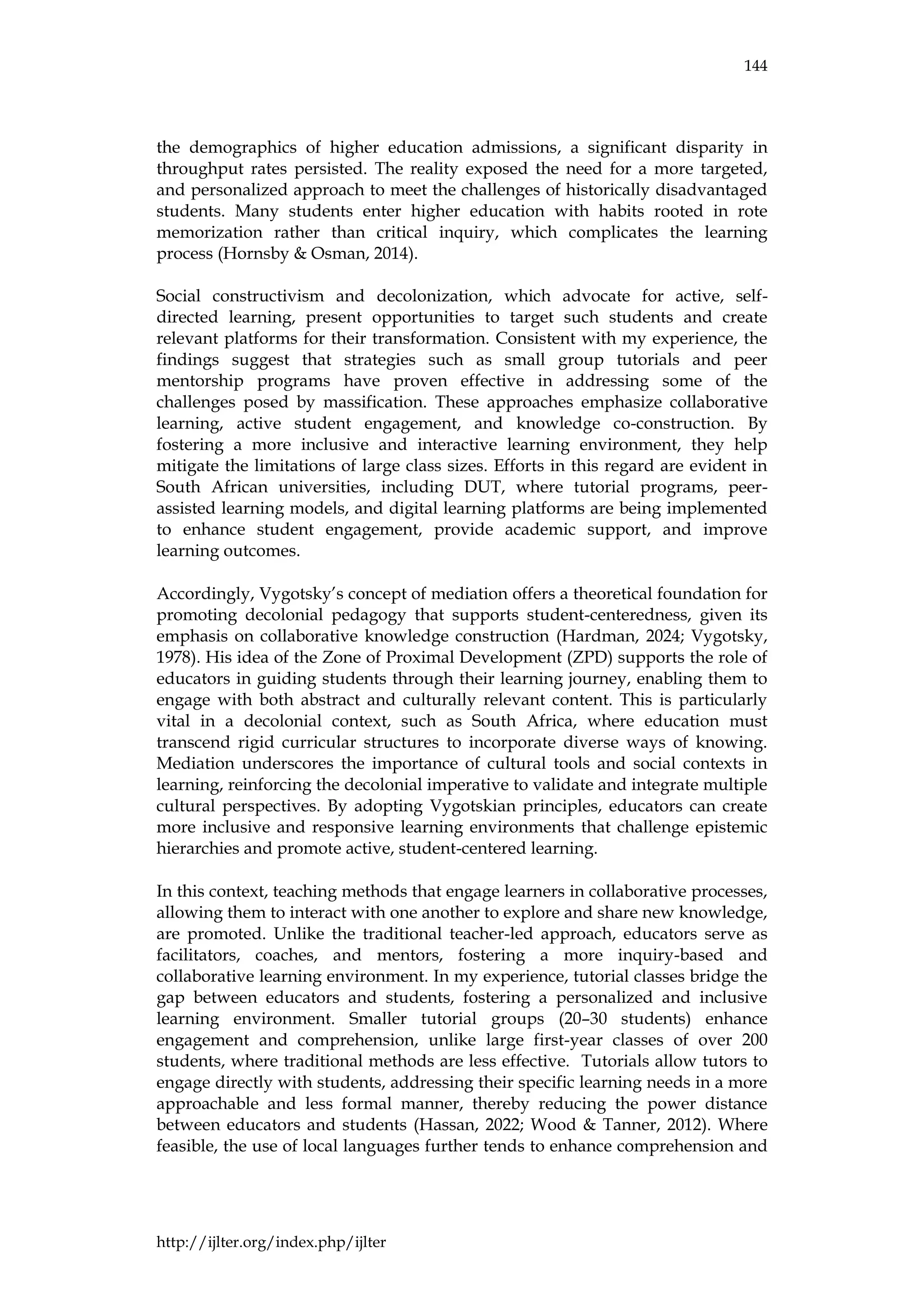

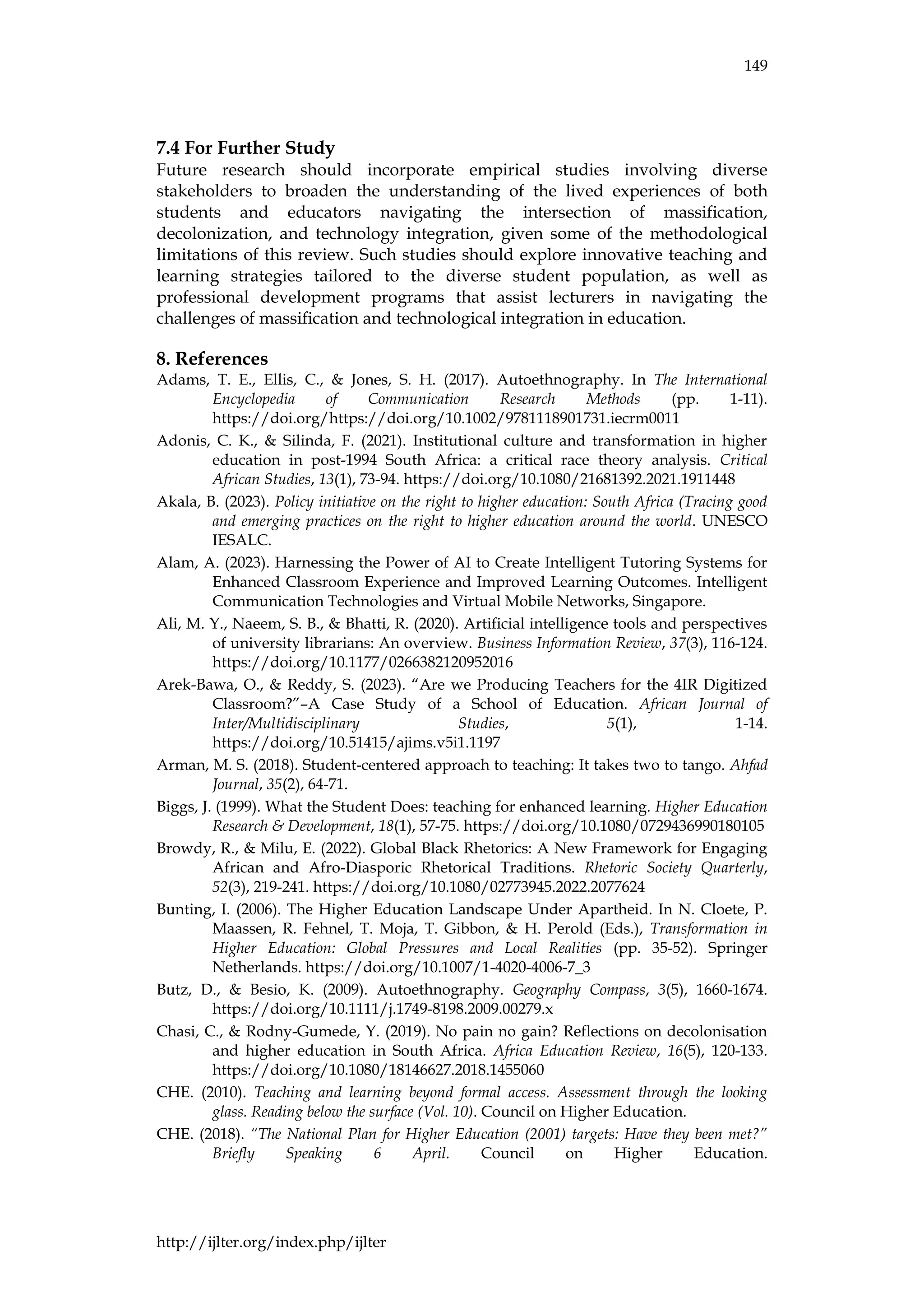

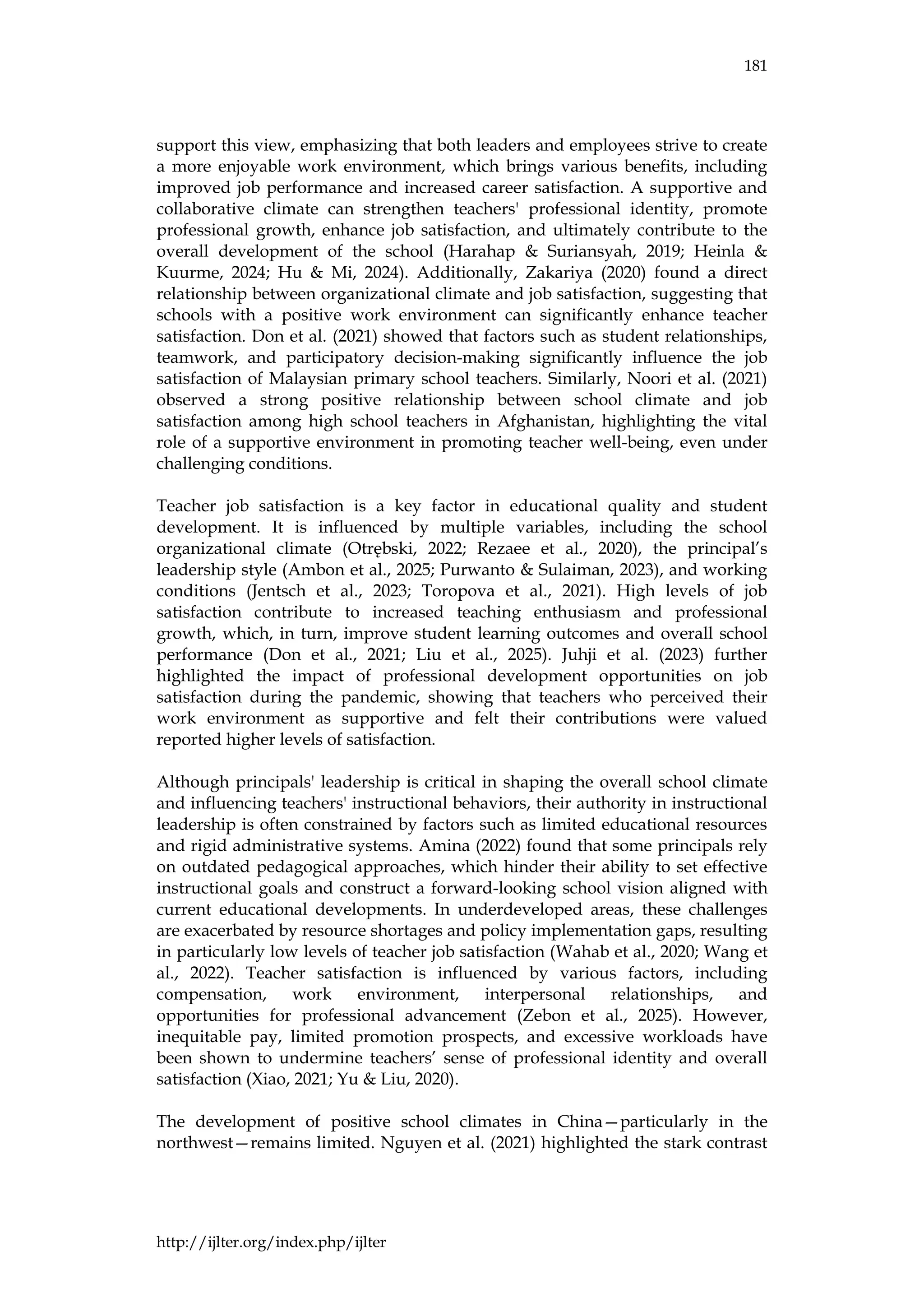

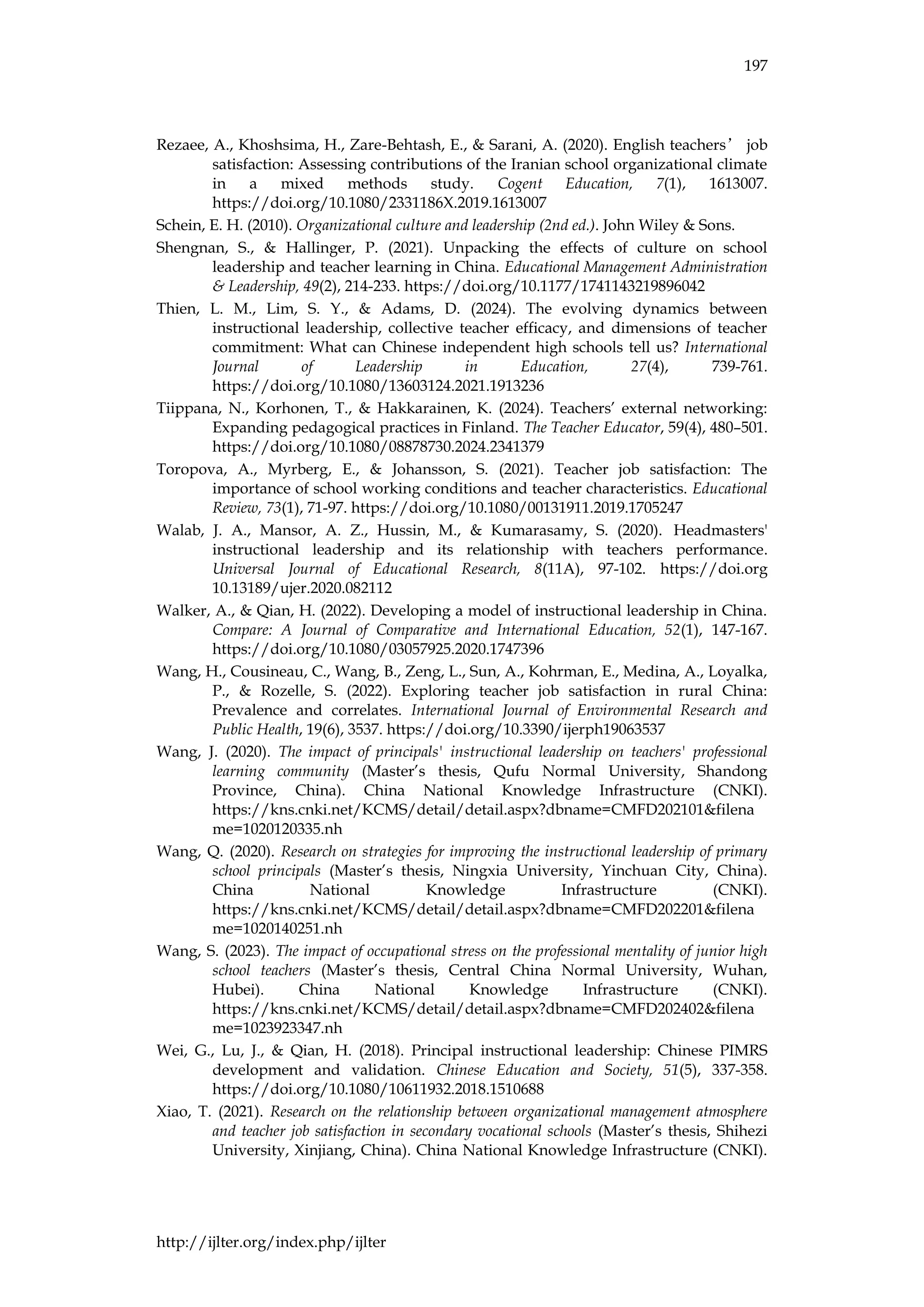

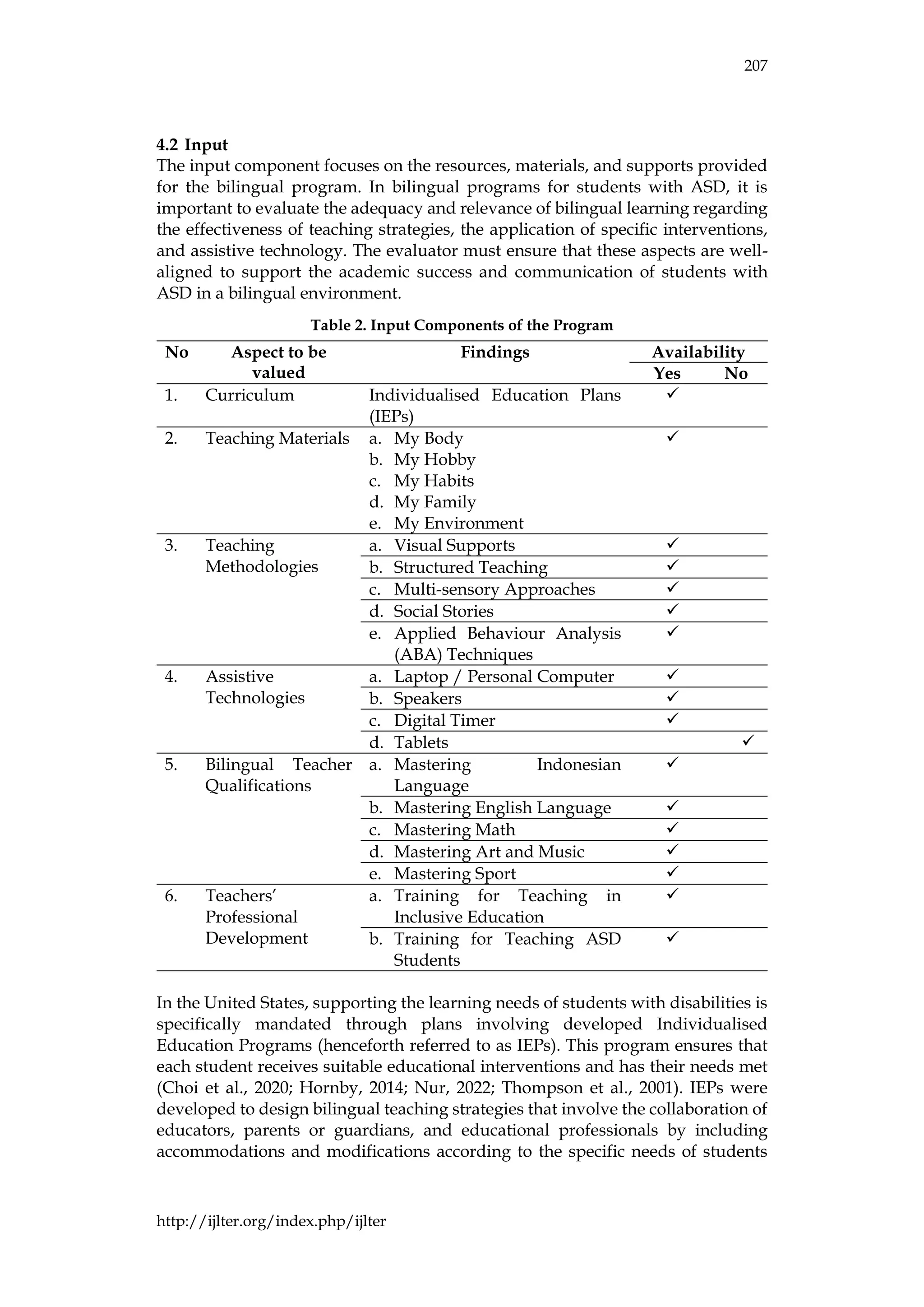

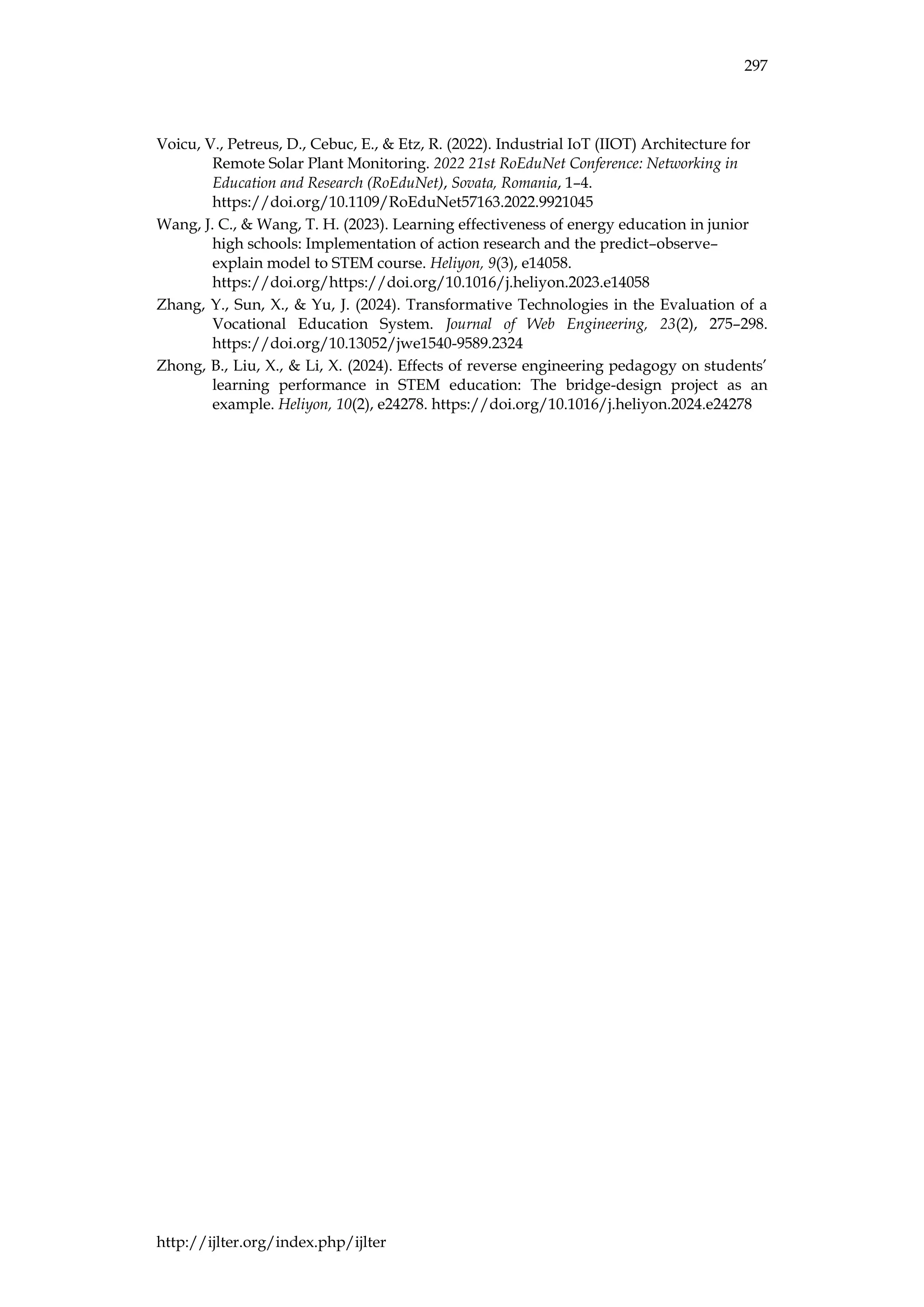

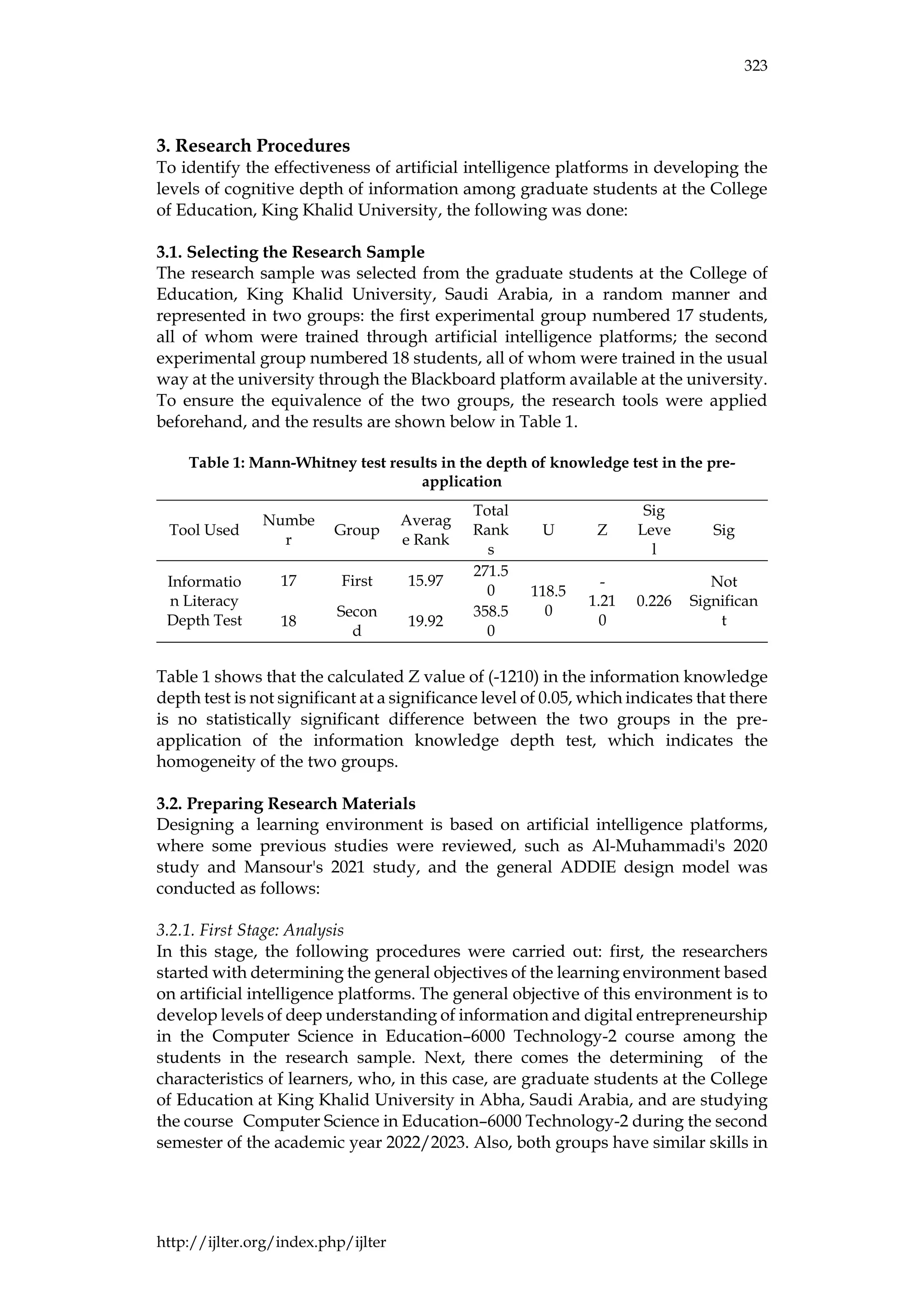

Table 4: Results of the multinomial logistic regression effect estimation analysis in

the intervention group

Logit estimate (SE) Odds ratio [95% CI]

Outcomes Low vs.

Middle

High vs.

Middle

Low vs. Middle High vs. Middle

Grade 4

Memory structure

of problems and

solutions

_0.35 (0.20) 0.23 (0.22) 0.821 [0.572,

1.043]

1.352 [0.831,

1.973]

Ability to analyze

problems and

solutions

_0.04 (0.12) 0.55**

(0.15)

0.981 [0.889,

1.302]

1.734 [1.420,

2.341]

Memory structure

of comparing

_0.31* (0.15) 0.25* (0.13) 0.763 [0.682,

0.976]

1.281 [1.021,

1.567]

Ability to

compare

_0.28* (0.14) 0.09 (0.14) 0.872 [0.689,

0.989]

1.089 [0.840,

1.510]

Memory structure

of main ideas

_0.68**

(0.12)

0.73**

(0.15)

0.621 [0.524,

0.752]

3.052 [1.663,

2.782]

Ability to identify

main ideas

_0.74**

(0.12)

0.71** 0.16) 0.572 [0.482,

0.683]

3.012 [1.534,

2.701]

Grade 5

Memory structure

of problems and

solutions

_0.18 (0.22) 0.35 (0.21) 0.951 [0.682,

1.352]

1.510 [0.952,

2.125]

Ability to analyze

problems and

solutions

_0.08 (0.12) 0.39**

(0.12)

0.942 [0.762,

1.271]

1.561 [1.173,

1.832]

Memory structure

of comparing

_0.02 (0.18) 0.61**

(0.13)

0.985 [0.720,

1.481]

1.770 [1.491,

2.251]

Ability to

compare

_0.42* (0.15) 0.21 (0.13) 0.741 [0.564,

0.957]

1.215 [0.852,

1.632]

Memory structure

of main ideas

_0.47**

(0.13)

0.91 (0.13) 0.642 [0.489,

0.784]

2.541 [1.925,

3.086]

Ability to identify

main ideas

_0.72**

(0.12)

0.82**

(0.14)

0.562 [0.451,

0.692]

2.351 [1.842,

2.892]

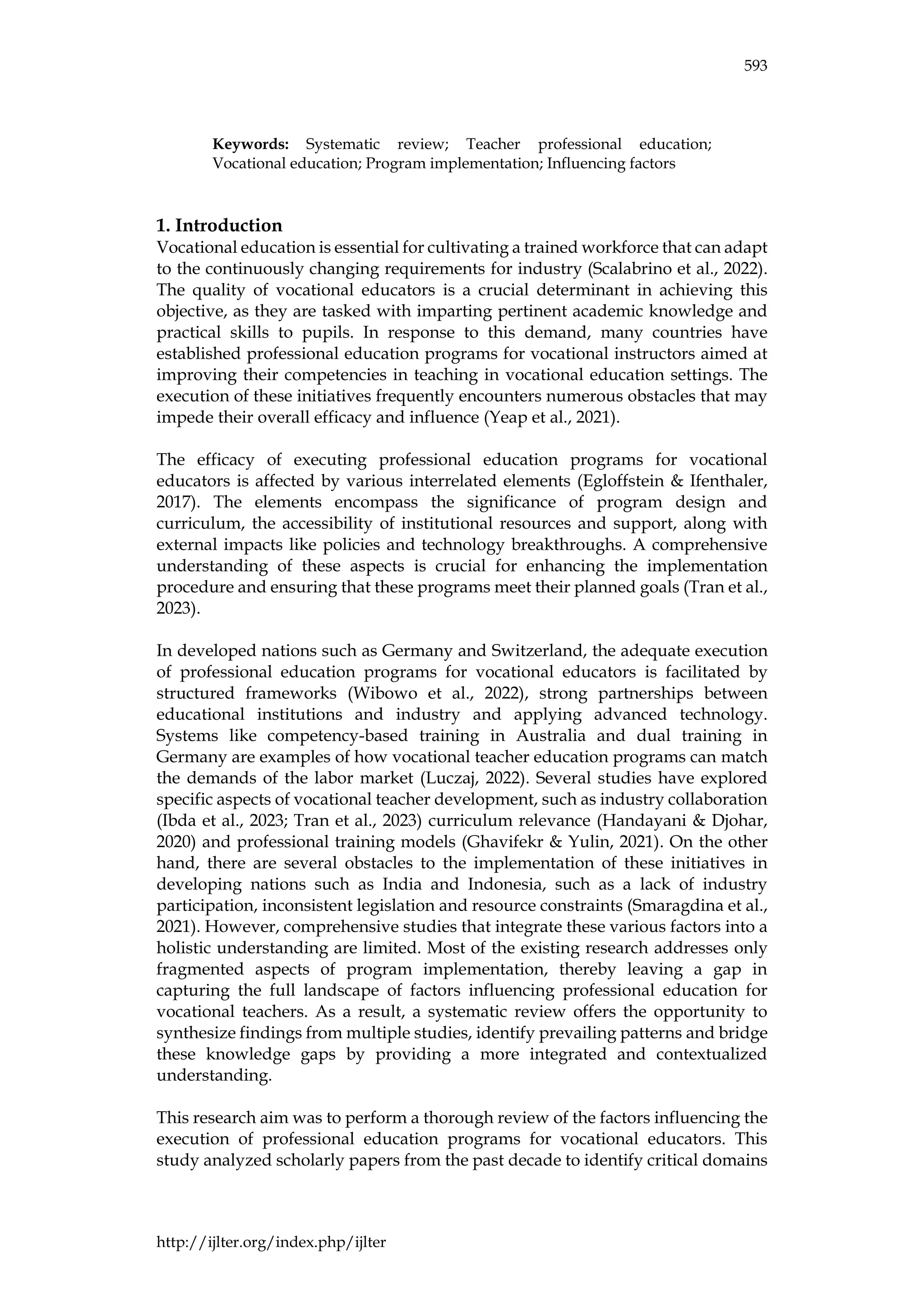

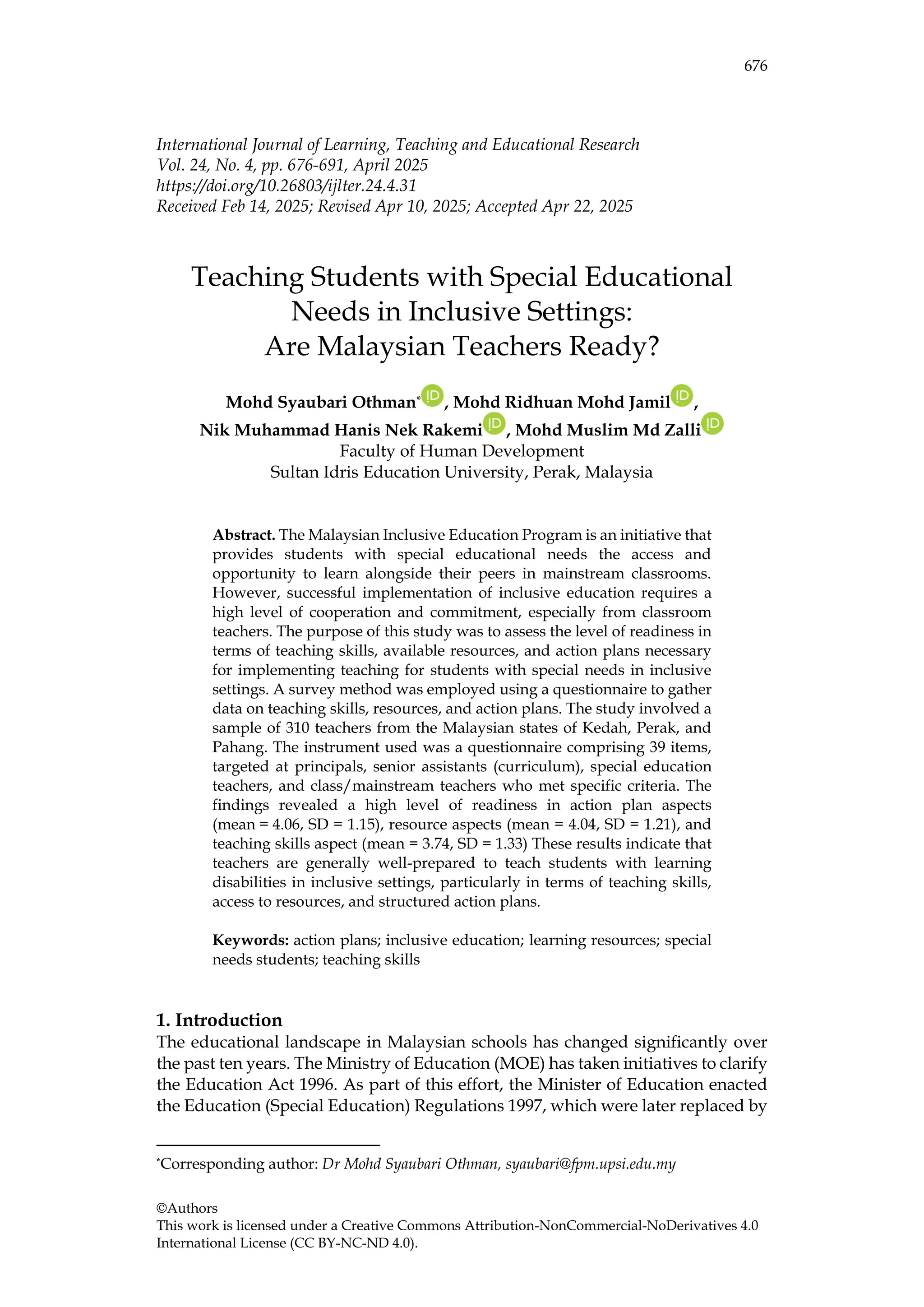

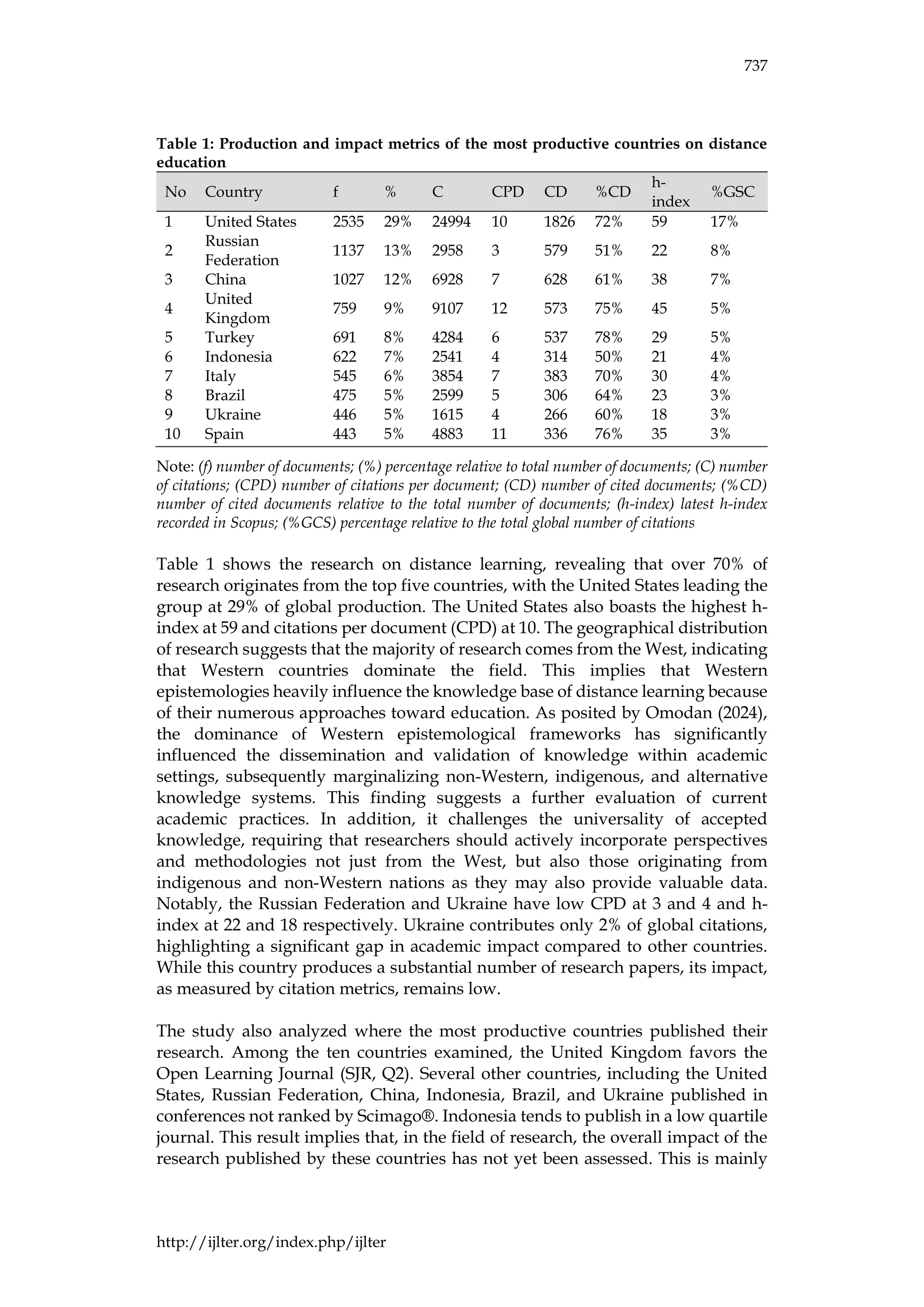

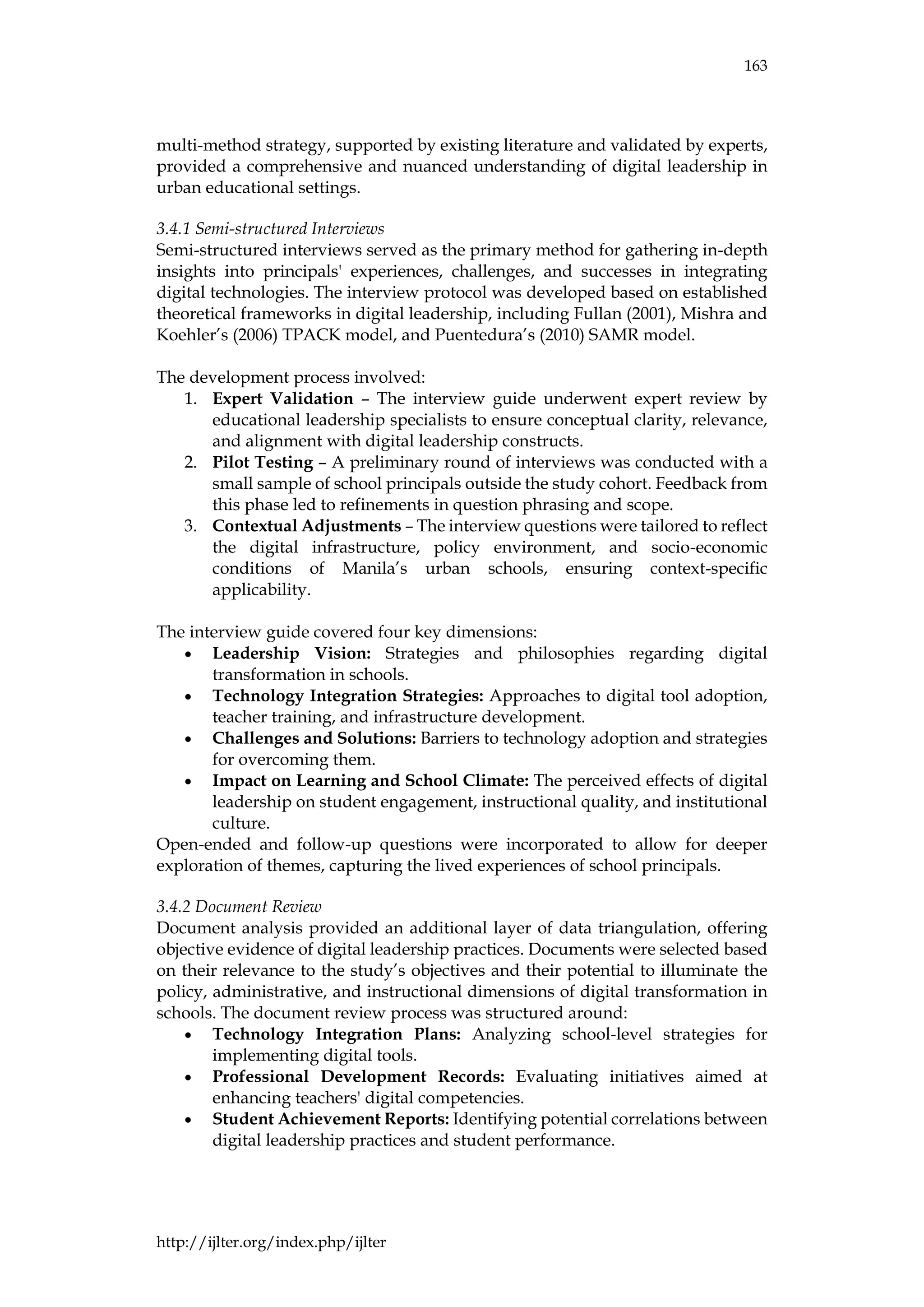

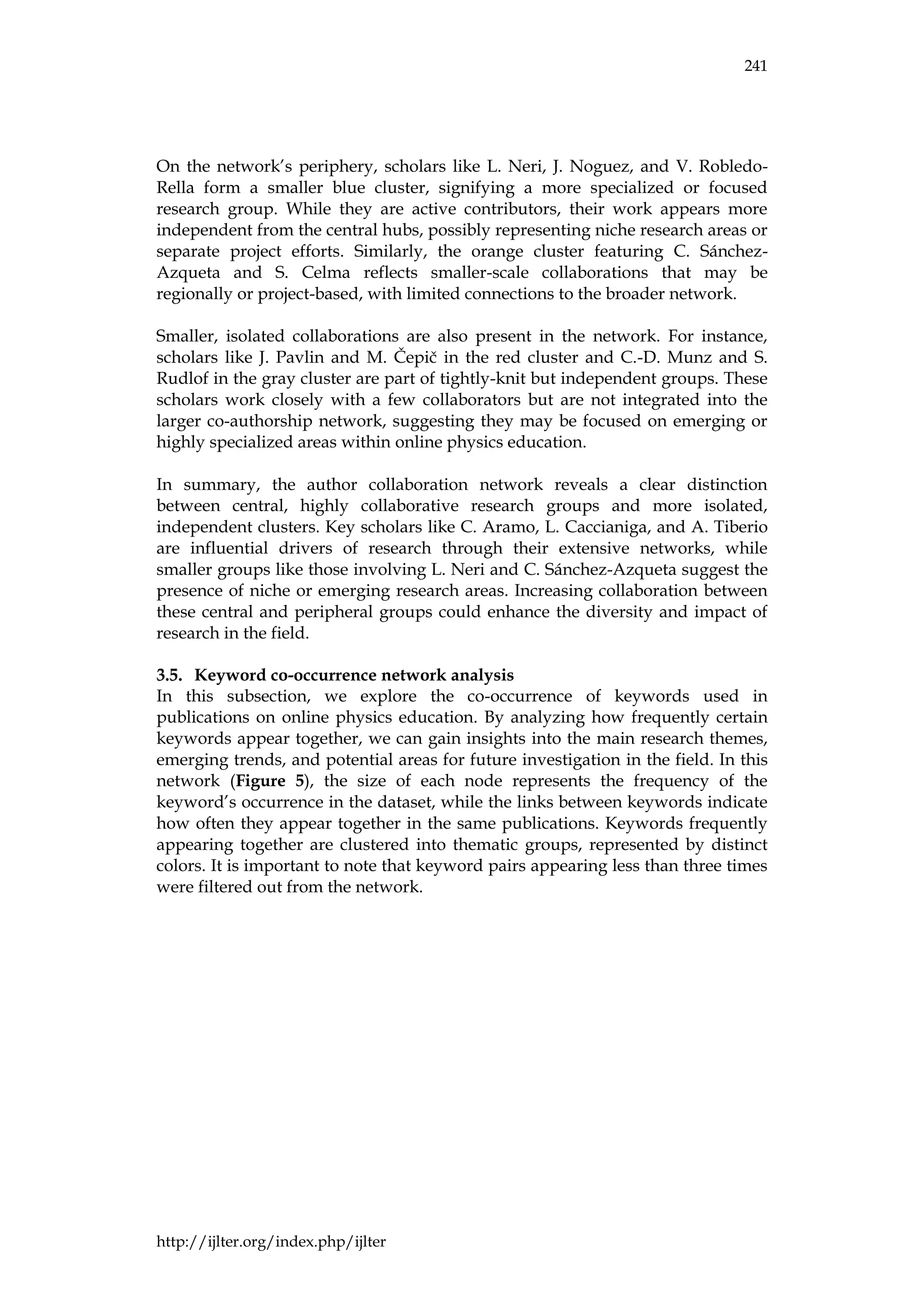

Based on the explanation, the TuinLec intervention significantly improved the

organized memory structure of grades four and five in every aspect assessed,

except for memory structure and solutions. Students with demographic

backgrounds, reading skills, and memory structures that were equivalent in the

TuinLec intervention group tended to show higher improvements in organized

memory structures than in the control group. Another finding was a significant

interaction between the experimental group and early organized memory

structures on the competence of main idea memory structures and the ability to

analyze main ideas in the posttest phase. A significant interaction pattern was also

found between the pretest conditions and memory structures that were at a high

level. This interaction showed that students who received the TuinLec

intervention showed a more significant increase in organized memory structures

compared to the control group. So, TuinLec was also able to promote students’

hierarchical memory structures and improve reading comprehension skills.

Improvements in students’ memory structures and reading comprehension skills](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol24no4april2025-250522164800-dd6d954c/75/IJLTER-ORG-Volume-24-Number-4-April-2025-71-2048.jpg)

![90

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

6.4 Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that there are no competing interests that could influence the

research or its outcomes. Neither of us has any financial, professional, or personal

relationships that could have inappropriately impacted or biased our work.

6.5 Acknowledgement

The researchers acknowledge the research participants for their willingness to

respond to the interview questions, which led to the realisation of this study.

7. References

Bueno-Alastuey, M. C., & Villarreal, I. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ perceptions and

training contributions to ICT use. Estudios Sobre Educación, 41, 107-129.

http://dx.doi.org/10.15581/004.41.002

Bwalya, A., Rutegwa, M., Tukahabwa, D., & Mapulanga, T. (2023). Enhancing pre-

service biology teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge through

a TPACK-based technology integration course. Journal of Baltic Science Education,

22(6), 956–973. https://doi.org/10.33225/jbse/23.22.956

Diab, A., & Green, E. (2024). Cultivating resilience and success: Support systems for

novice teachers in diverse contexts. Education Sciences, 14(7), 711.

https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14070711

Falloon, G. (2020). From digital literacy to digital competence: The teacher digital

competency (TDC) framework. Educational Technology Research and Development,

68, 2449-2472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09767-4

Fessl, A., Maitz, K., Paleczek, L., Köhler, T., Irnleitner, S., & Divitini, M. (2022).

Designing a curriculum for digital competencies for teaching and learning.

European Conference on E-Learning, 21(1), 469–471.

https://doi.org/10.34190/ecel.21.1.723

Foulger, T. S., Graziano, K. J., Schmidt-Crawford, D., & Slykhuis, D. A. (2017). Teacher

educators’ technology competencies. Journal of Technology and Teacher

Education, 25(4), 413–448. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/181966

Galindo-Domínguez, H., & Bezanilla, M. (2021). Digital competence in the training of

pre-service teachers: Perceptions of students in the degrees of early childhood

education and primary education. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education,

37, 262–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/21532974.2021.1934757

Gath, M., Horwood, L., Gillon, G., McNeill, B., & Woodward, L. (2025). Longitudinal

associations between screen time and children’s language, early educational

skills, and peer social functioning. Developmental Psychology [Ahead of Print].

https://doi.org/10.1037/de v0001907

Gertsog, G. A., Danilova, V. V., Savchenkov, A. V., & Korneev, D. N. (2017). Professional

identity for successful adaptation of students' participative approach. Rupkatha

journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 9(1), 301–311.

http://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v9n1.30

Hsu, P. S. (2016). Examining current beliefs, practices, and barriers to technology

integration: A case study. TechTrends, 60, 30–40.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-015-0014-3

Hu, X., Chiu, M. M., Leung, W. M. V., & Yelland, N. (2021). Technology integration for

young children during COVID‐19: Towards future online teaching. British

Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1513–

1537. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13106](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol24no4april2025-250522164800-dd6d954c/75/IJLTER-ORG-Volume-24-Number-4-April-2025-97-2048.jpg)

![151

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

Grewe, M., & Gie, L. (2023). Can virtual reality have a positive influence on student

engagement? South African Journal of Higher Education, 37(5), 124-141.

https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-high_v37_n5_a10

Hardman, J. (2024). Decolonising pedagogy: A critical engagement with debates in the

university in South Africa. Journal of Education (94), 146-160.

https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i94a09

Hassan, S. (2022). Reducing the colonial footprint through tutorials: A South African

perspective on the decolonisation of education. South African Journal of Higher

Education, 36(5), 77-97. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-high_v36_n5_a5

Heleta, S. (2016). Decolonisation of higher education: Dismantling epistemic violence

and Eurocentrism in South Africa. Transformation in Higher Education, 1(1), 1-8.

https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-57acdfafc

Hornsby, D. J., & Osman, R. (2014). Massification in higher education: Large classes and

student learning. Higher education, 67, 711-719. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-

014-9733-1

Jacobs, C. (2023). Contextually responsive and knowledge-focused teaching: disrupting

the notion of ‘best practices’. Critical studies in teaching and learning, 9(SI).

https://doi.org/10.14426/cristal.v9iSI.1782

Kabudi, T. M. (2022). Artificial intelligence for quality education: Successes and

challenges for AI in meeting SDG4. International Conference on Social

Implications of Computers in Developing Countries,

Lubinga, S. N., Maramura, T. C., & Masiya, T. (2023). Adoption of Fourth Industrial

Revolution: challenges in South African higher education institutions. Journal of

Culture and Values in Education, 6(2), 1-17.

https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.46303/jcve.2023.5

Luckett, K. (2023). Reflections from South Africa on Language, Culture and

Decolonisation. South African Journal of Science, 119(4), 1.

https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2023/15640

Mafenya, N. P. (2022). Exploring technology as enabler for sustainable teaching and

learning during Covid-19 at a university in South Africa. Perspectives in

Education, 40(3), 212-223. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-persed_v40_n3_a14

Maringe, F., & Sing, N. (2014). Teaching large classes in an increasingly

internationalising higher education environment: pedagogical, quality and

equity issues. Higher education, 67(6), 761-782. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-

013-9710-0

Matoti, S. N., & Lenong, B. (2018). Teaching large classes at an institution of higher

learning in South Africa. Proceedings of International Academic Conferences,

Mcinziba, D. Z. (2020). An analysis of the role of social media in teaching and learning at a

higher education institution in South Africa Cape Peninsula University of

Technology].

Mokoena, T. D. (2021). Teaching in the Time of Massification: Exploring Education Academics’

Experiences of Teaching Large Classes in South African Higher Education [Master

Thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal]. Edgewood, Durban.

Moloi, T., & Salawu, M. (2022). Institutionalizing technologies in South African

universities towards the fourth industrial revolution. International Journal of

Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 17(3), 204-227.

https://doi.org/10.3991/ijet.v17i03.25631

Moodley, P. (2015). Student overload at university: large class teaching challenges: part

1. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(3), 150-167.

https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC176230](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol24no4april2025-250522164800-dd6d954c/75/IJLTER-ORG-Volume-24-Number-4-April-2025-158-2048.jpg)

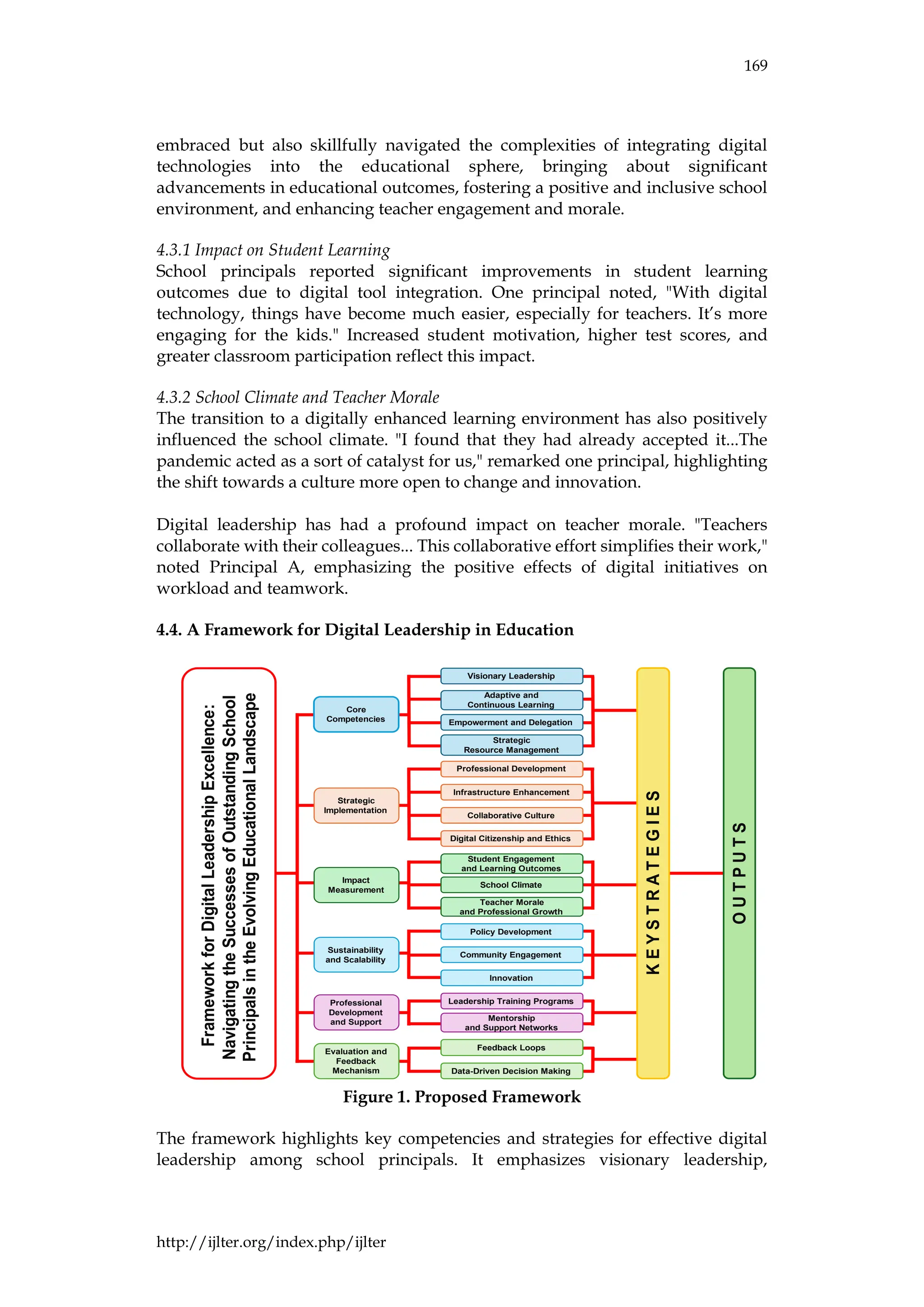

![165

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

3.6. Data Gathering Procedure

The data collection process followed a structured approach to ensure accuracy

and reliability.

1. Preparation Phase – The researcher secured necessary approvals from the

Division of City Schools, Manila, and obtained informed consent from

selected school principals. A schedule for data collection was coordinated

with participants.

2. Data Collection – The researcher conducted interviews, gathered relevant

documents, and observed classrooms over a specified period. Interviews

were recorded and transcribed for analysis. Documents were collected and

categorized, while observations were conducted using a structured

checklist to maintain consistency.

3. Validation and Triangulation – After data collection, interviews were

reviewed through member checking, allowing participants to verify their

responses. Findings from different sources were cross-validated to ensure

consistency and credibility. Peer debriefing with educational experts

further refined interpretations and minimized bias.

4. Data Organization and Storage – All collected data were securely stored

and systematically categorized for analysis. Transcriptions, notes, and

documents were organized to facilitate thematic coding and

interpretation.

This structured process ensured a rigorous and ethical approach to gathering data

on digital leadership in Manila’s schools.

3.8. Ethical Considerations and Confidentiality Measures

Across all data gathering methods, ethical considerations and confidentiality

measures were paramount. The study adhered to ethical guidelines for research

involving human subjects, ensuring that participation was voluntary, informed

consent was obtained, and the anonymity and privacy of participants were

protected (American Educational Research Association [AERA], 2011). Data

storage and handling procedures were designed to ensure that all collected data

were secure and accessible only to the research team, with electronic data

encrypted and stored in password-protected files.

By implementing these rigorous ethical and confidentiality measures, the study

aimed to uphold the highest standards of research integrity and respect for

participants. These measures not only safeguarded the participants' rights and

welfare but also enhanced the credibility and trustworthiness of the research

findings.

3.9. Data Processing and Analysis

This study employed thematic analysis to analyze data from semi-structured

interviews (primary), document reviews, and classroom observations

(supplementary), ensuring a comprehensive and credible understanding of

digital leadership among school principals in the Division of City Schools, Manila.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol24no4april2025-250522164800-dd6d954c/75/IJLTER-ORG-Volume-24-Number-4-April-2025-172-2048.jpg)

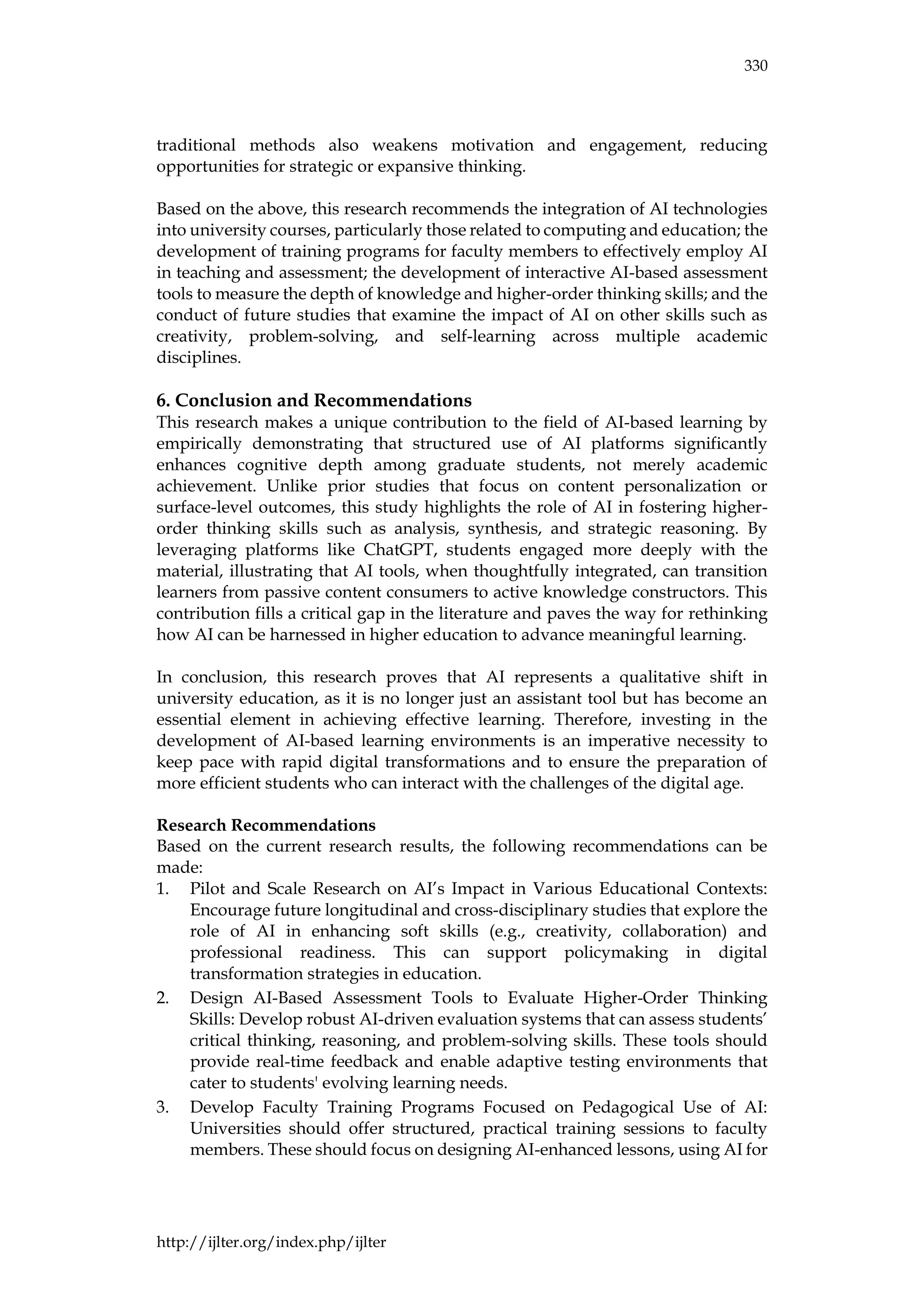

![315

Karuppannan, S., & Mohammed, L. A. (2020). Predictive factors associated with online

learning during Covid-19 pandemic in Malaysia: A conceptual framework.

International Journal of Management and Human Science, 4(4), 19–29.

https://ejournal.lucp.net/index.php/ijmhs/article/view/1236

Krishnan, I. A., Ching, H. S., Ramalingam, S., Maruthai, E., Kandasamy, P., De Mello, G.,

Munian, S., & Ling, W. W. (2020). Challenges of learning English in the 21st

century: Online vs. traditional during Covid-19. Malaysian Journal of Social Sciences

and Humanities, 5(9), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.47405/mjssh.v5i9.494

Levidze, M. (2024). Mapping the research landscape: A bibliometric analysis of e-learning

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Heliyon, 10(13), 1–18.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33875

Mohammed, B. A., & Yaakoub, L. E. (2024). Teachers' and students' perspectives towards the

use of web-based technologies to enhance speaking skills of EFL students [Doctoral

dissertation, University Center of Abdalhafid Boussouf, Mila, Algeria].

Nasri, M. N., Husnin, H., Mahmud, S. N. D., & Halim, L. (2020). Mitigating the Covid-19

pandemic: A snapshot from Malaysia into the coping strategies for pre-service

teachers’ education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 546–553.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2020.1802582

Onojah, A., & Onojah, A. A. (2020). Inspiration of technology; effect of Covid-19 pandemic

on education. AIJR Preprints, 120(1). 20–28.

https://doi.org/10.21467/preprints.120

Sornasekaran, H., Mohammed, L. A., & Amidi, A. (2020). Challenges associated with e-

learning among ESL undergraduates in Malaysia: A conceptual

framework. International Journal of Management and Human Science, 4(4), 30–38.

https://ejournal.lucp.net/index.php/ijmhs/article/view/1239

Wahas, Y. (2023). Challenges of e-learning faced by ESL learners during the Covid-19

pandemic: A case study. International Journal of Language and Translation

Research, 3(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.22034/IJLTR.2023.169033

Wen, K. Y. K., & Kim Hua, T. (2020). ESL teachers' intention in adopting online educational

technologies during the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Education and E-Learning

Research, 7(4), 387–394.

http://doi.org/10.20448/journal.509.2020.74.387.394

Yazid, N. H. M., Sulaiman, N. A., & Hashim, H. (2024). A systematic literature review of

web-based learning and digital pedagogies in grammar education (2015-2024).

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 14(9), 2524–

2542. https://doi.org/10.6007/ijarbss/v14-i9/22858

Ying, Y. H., Siang, W. E. W., & Mohamad, M. (2021). The challenges of learning English

skills and the integration of social media and video conferencing tools to help ESL

learners coping with the challenges during COVID-19 pandemic: A literature

review. Creative Education, 12(7), 1503–1516.

https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2021.127115

Zhang, X. (2022). Demystifying the challenges of university students’ web-based learning:

A qualitative case study. Education and Information Technologies, 27(7), 10161–

10178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10974-0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol24no4april2025-250522164800-dd6d954c/75/IJLTER-ORG-Volume-24-Number-4-April-2025-322-2048.jpg)

![331

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

formative assessments, and developing strategies to mitigate overreliance on

AI, ensuring students remain active participants in the learning process.

4. Integrate AI Platforms into University Curricula Across Disciplines:

University decision-makers should implement AI-supported learning

environments not only in computer-related courses but across various

academic fields to promote cognitive depth, critical analysis, and synthesis of

knowledge.

5. This research recommends the development of clear regulatory and ethical

frameworks for the use of artificial intelligence in education, balancing the

benefits of technological capabilities with the reduction of associated risks,

particularly in educational environments that seek to develop deep thinking

and cognitive independence.

6. Conduct longitudinal studies to measure the sustainability of the cognitive

impact resulting from the use of artificial intelligence and the extent to which

acquired skills remain after varying periods of time.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict regarding the publication of this

paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate

Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through small

group research under grant number (RGP1/125/45 AH).

7. References

Abdel Aleem, Saudi, & Ibrahim, W. S. E. (2022). The effectiveness of a website based on

the depth of knowledge model in developing levels of cognitive depth associated

with the skills of using cloud computing applications among educational

technology students. Educational Technology, 2(32), 3–47.

https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/16046

Abdel Samee, M. A. H. (2019). Student integration as an introduction to the quality of learning

outcomes. Dar Al-Masirah for Publishing, Distribution and Printing.

Abdul Latif, O. G., Mahdi, Y. H., & Ibrahim, S. K. (2020). The effectiveness of an artificial

intelligence-based teaching system to develop a deep understanding of nuclear

reactions and the ability to learn independently among secondary school

students. Journal of Scientific Research in Education, 21(4), 307–349.

https://doi.org/10.47750/pegegog.12.03.18

Abdullah, A. G. (2022). Using Google interactive applications in teaching mathematics to

develop levels of depth of mathematical knowledge and technological literacy

among first-year secondary school students. Journal of Mathematics Education,

25(1), 209–275. https://doi.org/10.21608/armin.2022.232845

Abu Muqaddam, R. A. (2024). The degree of use of artificial intelligence applications in self-

learning among graduate students in Jordanian universities [Unpublished master's

thesis]. Middle East University.

Al-Feel, H. (2018). Modern educational variables in the Arab environment – authentication and

localization. Anglo-Egyptian Library.

Ali, S. A. H. (2021). Using a platform-based reciprocal teaching strategy and its impact on

developing the skills of designing educational situations and the levels of depth](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol24no4april2025-250522164800-dd6d954c/75/IJLTER-ORG-Volume-24-Number-4-April-2025-338-2048.jpg)

![332

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

of knowledge for students of educational technology at the Faculty of Specific

Education. Journal of the Faculty of Education, 45(1), 379–428.

https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14121323

Al-Lawzi, A. M., & Metwally, S. B. (2021). Employing e-learning anchors in teaching an

educational assessment course to develop levels of depth of knowledge,

evaluation competencies and professional self-affirmation for student teachers at

the Faculty of Home Economics. Journal of the Faculty of Education, Sohag, 1(82),

313–406.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2014.05.003

Al-Muhammadi, G. A. (2020). Designing an adaptive learning environment based on artificial

intelligence and its effectiveness in developing digital technology application skills in

scientific research and future information awareness among gifted female students in

secondary school [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Umm Al-Qura University.

Al-Rashidi, S., & Al-Farani, L. (2024). The effectiveness of using the artificial intelligence

program Typeset.io in developing scientific research skills and graduate students’

attitudes towards it. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 44(1),

136–170. https://doi.org/10.18576/isl/130304

Al-Ubaid, A. A. R. (2020). The effect of employing project-based learning to develop

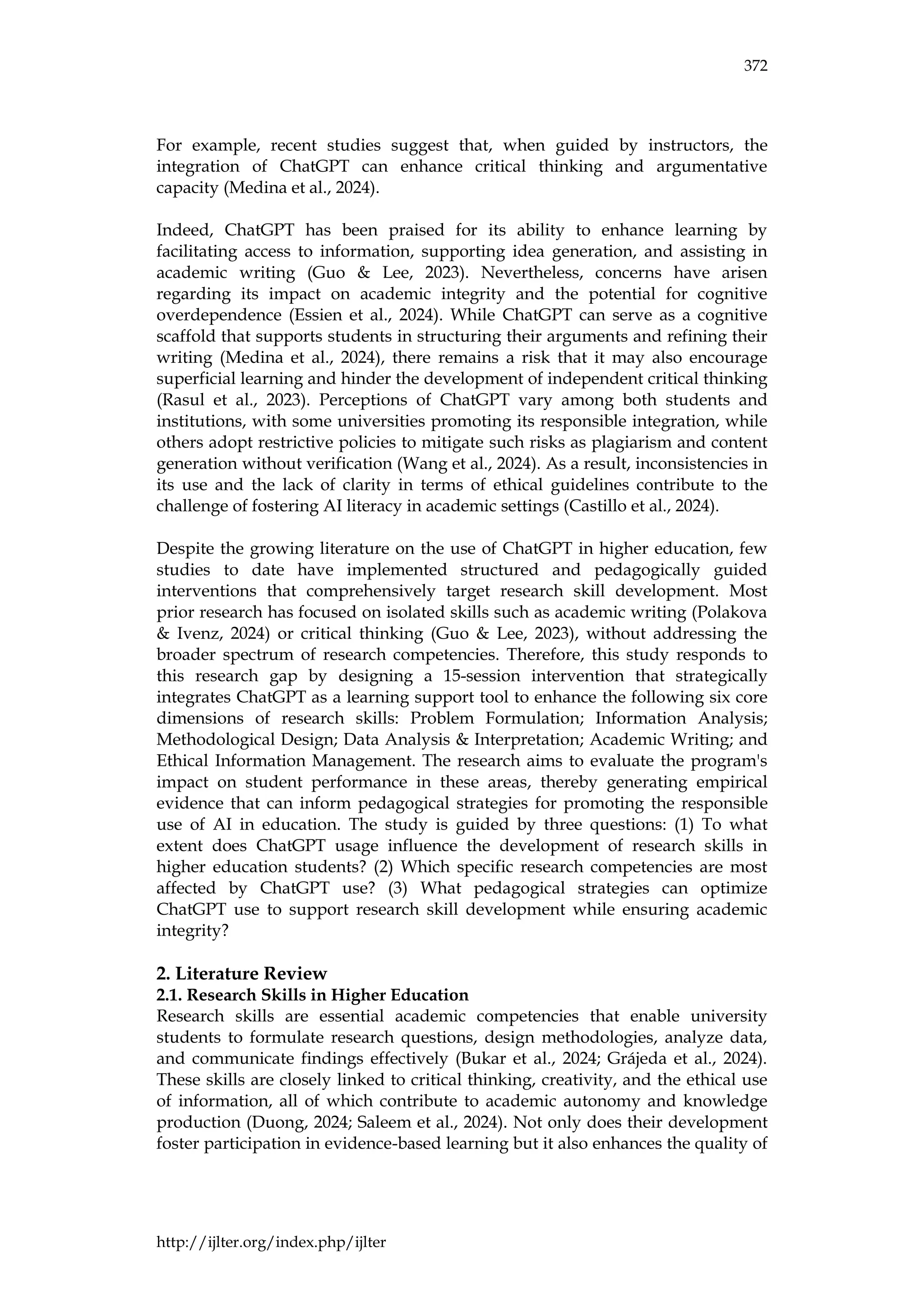

educational design skills for mobile learning and develop levels of depth of

knowledge among e-learning diploma students at Princess Nourah bint Abdul

Rahman University. Journal of the Association of Arab Universities, 18(2), 65–121.

https://doi.org/10.31246/mjn-2019-0072

Al-Zain, A. A. (2021). Smart content industry. Intellectual Creativity for Publishing and

Distribution.

Capella, M. (2025, February 13). La inteligencia artificial, aliada y riesgo en el aprendizaje

universitario, según un estudio de la UIB. Cadena SER.

Dhikr Allah, A. (2022). The penetration of technology as a substitute for humans and its

impact on the economy. In A. Amr (Ed.), Posthumanism – Virtual worlds and their

impact on humans (pp. 205–229). Afak Al-Ma'rifa Publishing and Distribution

Company.

Fares, N. M. (2020). Using a learning environment based on content sharing networks and

its impact on achievement, reflective thinking, and cognitive absorption among

students of educational technology. Educational Journal, 79(1), 765–809.

https://doi.org/10.58837/chula.educu.48.1.12

Halaweh, M. (2023). ChatGPT in education: Strategies for responsible implementation.

Contemporary Educational Technology, 15(2), ep421.

https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/13036

Hamed, M. A. (2024). The effect of smart educational support through an interactive

website based on artificial intelligence on the development of the academic

performance of graduate students. Journal of the Faculty of Education, 40(8), 2–91.

https://doi.org/10.52098/airdj.202138

Hwang, G. J., & Chang, C. Y. (2024). The impact of AI-based learning systems on higher

education: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 195, 104823.

https://doi.org/10.21428/8c225f6e.33570bb1

Ibrahim, M. N., & Al-Omari, A. B. (2021). Open educational resources: Unlimited options. Al-

Obeikan Library.

Lo, C. K. (2023). What is the impact of ChatGPT on education? A rapid review of the

literature. Education Sciences, 13(4), 410.

https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13040410

Lu, H. (2025, February 25). AI doesn’t shortchange learning. It enhances it. Stanford

Graduate School of Business.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol24no4april2025-250522164800-dd6d954c/75/IJLTER-ORG-Volume-24-Number-4-April-2025-339-2048.jpg)

![333

http://ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter

https://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/openforum/article/ai-education-

20168638.php

Mansour, M. M. (2021). The effect of the difference in the two patterns of collaborative

learning based on artificial intelligence through chatbot on the development of

deep understanding skills and the ability to learn independently among students

of the professional diploma in education. International Journal of E-Learning, 4(3),

357–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2019.1665571

Mohamed, A. A. S., & Mohamed, K. M. (2020). Artificial intelligence applications and the

future of educational technology. Arab Publishing Group.

Mohamed, H. R. (2021). Artificial intelligence systems and the future of education. Studies

in University. Education, 52(52), 573–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-

72080-3_4

Oki, B., Rogowski, B., & Sijnowski, T. J. (2022). Learning outside the ordinary (E. Al-Khadhra

& D. Al-Qurna, Trans.). Al-Obeikan Library.

Omar, A. A. R. (2022). Introduction to modern entrepreneurship. Dar Al-Ebdaa Al-Thaqafi.

Ritter, S., Murray, R. C., & Hausmann, R. G. (2018). Educational software design:

Education, engagement, and productivity concerns. In R. D. Roscoe, S. D. Craig,

& I. Douglas (Eds.), End-user considerations in educational technology design (pp. 35–

51). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-2639-1.ch002

Robertson, C. M. (2013). The mediating role of learning styles and strategies in the relationship

between cognitive ability and academic performance [Unpublished doctoral

dissertation]. University of Pretoria.

Shrum, B. L. (2018). Leading 21st century schools – Harnessing technology for integration and

achievement (I. A. Al-Saadoun, Trans.). King Saud University House. (Original

work published in 2015)

Thomas, J. (2017). Noticing and knowledge: Exploring theoretical connections between

professional noticing and mathematical knowledge for teaching. The Mathematics

Educator, 26(2), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.63301/tme.v26i2.2030

Wamdat. (2020). Promoting the culture of innovation in preparation for the fifties. Wamdat

Journal, 5(69), 13–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-61874-5_3

Zawacki-Richter, O., Dolch, C., & Qayyum, A. (2024). Artificial intelligence in higher

education: Opportunities and challenges. Journal of Educational Technology

Research, 41(2), 112–130. https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi30.1137

Zhai, X. (2022, December 27). ChatGPT user experience: Implications for education. SSRN.

https://ssrn.com/abstract=4312418 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4312418](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/vol24no4april2025-250522164800-dd6d954c/75/IJLTER-ORG-Volume-24-Number-4-April-2025-340-2048.jpg)