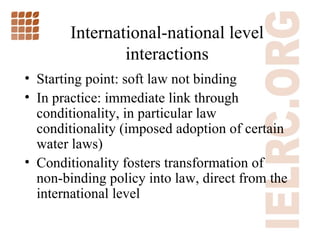

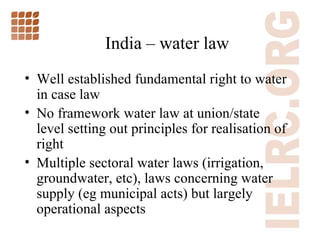

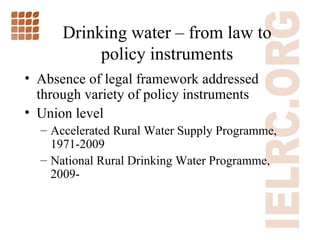

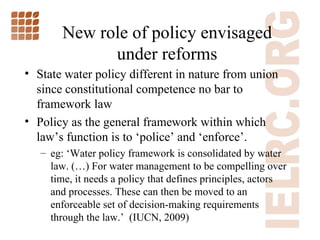

1. Water policy in India has effectively become water law as there is no comprehensive water law at the national level, only sectoral laws, and policies have directly shaped implementation and reforms.

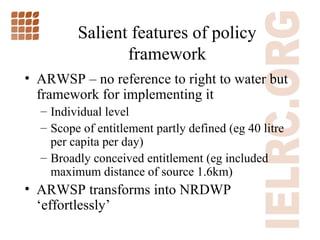

2. The right to water is recognized in case law but drinking water policy, not law, has defined entitlements like 40 liters per capita per day.

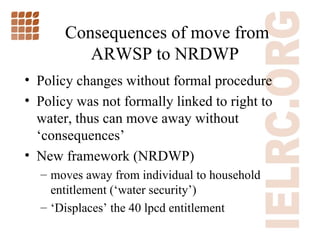

3. There are challenges to using policy instead of law for governance as policies can be changed without formal legal process and may not comply with legal principles.

![Is Water Policy The New Water Law? Reflections on India ’ s Experience Philippe Cullet Professor of international and environmental law SOAS – University of London [email_address] Some for All? Pathways and Politics in Water and Sanitation since New Delhi, 1990, 22-23 March 2011, IDS](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/idspresentation-110404103719-phpapp01/75/Is-Water-Policy-The-New-Water-Law-Reflections-on-India-s-Experience-1-2048.jpg)