This document summarizes the development of the ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders by the World Health Organization over several decades through extensive international consultation and research. Major projects developed diagnostic assessment instruments and conducted field trials in over 40 countries to refine the diagnostic classifications and criteria. The final classification and this clinical guidelines publication reflect contributions from experts and institutions around the world and represent an international collaboration to improve psychiatric diagnosis worldwide.

![8

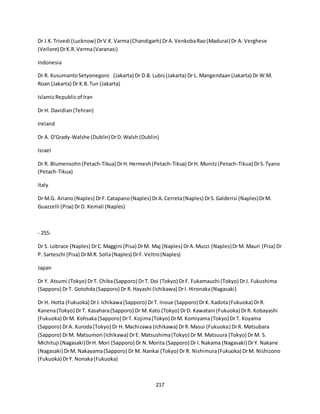

Chapter V, Mental and behavioural disorders, of ICD-10 is to be available in

severaldifferent versions for differentpurposes. This version, Clinical descriptions

and diagnostic guidelines, is intended for general clinical, educational and service

use. Diagnostic criteria for research has been produced for research purposes and

is designed to be used in conjunction with this book. The much shorter glossary

provided by Chapter V(F) for ICD-10 itself is suitable for use by coders or clerical

workers, and also serves as a reference point for compatibility with other

classifications; it is not recommended for use by mental health professionals.

Shorter and simpler versions of the classifications for use by primary health care

workers are now in preparation, as is a multiaxial scheme. Clinical descriptions

and diagnostic guidelines has been the starting point for the development of the

different versions, and the utmost care has been taken to avoid problems of

incompatibility between them.

Layout

It is important that users study this general introduction, and also read carefully

the additional introductory and explanatory texts at the beginning of several of

the individual categories. This is particularly important for F23.-(Acute and

transient psychotic disorders), and for the block F30-F39 (Mood [affective]

disorders). Because of the long-standing and notoriously difficult problems

associated with the description and classification of these disorders, special care

has been taken to explain how the classification has been approached.

For each disorder, a description is provided of the main clinical features, and also

of any important but less specific associated features. "Diagnostic guidelines" are

then provided in most cases, indicating the number and balance of symptoms

usually required before a confident diagnosis can be made. The guidelines are

worded so that a degree of flexibility is retained for diagnostic decisions in clinical

work, particularly in the situation where provisional diagnosis may have to be

made before the clinical picture is entirely clear or information is complete. To

avoid repetition, clinical descriptions and some general diagnostic guidelines are

provided for certain groups of disorders, in addition to those that relate only to

individual disorders.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-8-320.jpg)

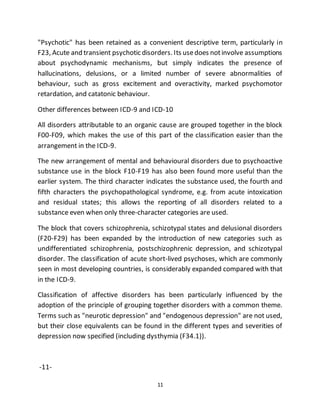

![10

The chapter that dealt with mental disorders in ICD-9 had only 30 three-character

categories (290-319); Chapter V(F) of ICD-10 has 100 such categories. A

proportion of these categories has been left unused for the time being, so as to

allow the introduction of changes into the classification without the need to

redesign the entire system.

ICD-10 as a whole is designed to be a central ("core") classification for a family of

disease- and health-related classifications. Some members of the family of

classifications are derived by using a fifth or even sixth character to specify more

detail. In others, the categories are condensed to give broad groups suitable for

use, for instance, in primary health care or general medical practice. There is a

multiaxial presentation of Chapter V(F) of ICD-10 and a version for child

psychiatric practice and research. The "family" also includes classifications that

cover information not contained in the ICD, but having important medical or

health implications, e.g. the classification of impairments, disabilities and

handicaps, the classification of procedures in medicine, and the classification of

reasons for encounter between patients and health workers.

Neurosis and psychosis

The traditional division between neurosis and psychosis that was evident in ICD-9

(although deliberately left without any attempt to define these concepts) has not

been used in ICD-10. However, the term "neurotic" is still retained for occasional

use and occurs, for instance, in the heading of a major group (or block) of

disorders F40-F48, "Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders". Except

for depressiveneurosis, mostof the disorders regarded as neuroses by those who

use the concept are to be found in this block,and the remainder are in the

subsequent blocks. Instead of following the neurotic-psychotic dichotomy, the

disorders are now arranged in groups according to major common themes or

descriptive likenesses, which makes for increased convenience of use. For

instance, cyclothymia (F34.0) is in the block F30-F39, Mood [affective] disorders,

rather than in F60-F69, Disorders of adult personality and behaviour; similarly, all

disorders associated with the use of psychoactive substances are grouped

together in F10-F19, regardless of their severity.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-10-320.jpg)

![20

Simple schizophrenia (F20.6) This category has been retained because of its

continued use in some countries, and because of the uncertainty about its nature

and its relationships to schizoid personality disorder and schizotypal disorder,

which will require additional information for resolution. The criteria proposed for

its differentiation highlight the problems of defining the mutual boundaries of this

whole group of disorders in practical terms.

Schizoaffectivedisorders (F25.-) The evidence at present available as to whether

schizoaffectivedisorders (F25.-) as defined in the ICD-10 should be placed in block

F20-F29 (schizophrenia, schizotypaland delusional disorders) or in F30-F39 (mood

[affective] disorders) is fairly evenly balanced. The final decision to place it in F20-

F29 was influenced by feedback from the field trials of the 1987 draft, and by

comments resulting from the worldwide circulation of the same draft to member

societies of the World Psychiatric Association. It is clear that widespread and

strong clinical traditions exist that favour its retention among schizophrenia and

delusional disorders. It is relevant to this discussion that, given a set of affective

symptoms, the addition of only mood-incongruent delusions is not sufficient to

change the diagnosis to a schizoaffective category. At least one typically

schizophrenic

-17-

symptom must be present with the affective symptoms during the same episode

of the disorder.

Mood [affective] disorders (F30-F39) It seems likely that psychiatrists will

continue to disagree about the classification of disorders of mood until methods

of dividing the clinical syndromes are developed that rely at least in part upon

physiological or biochemical measurement, rather than being limited as at

present to clinical descriptions of emotions and behaviour. As long as this

limitation persists, one of the major choices lies between a comparatively simple

classification with only a few degrees of severity, and one with greater details and

more subdivisions. The 1987 draft of ICD-10 used in the field trials had the merit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-20-320.jpg)

![22

-18-

should encourage the collection of information that will lead to a better

understanding of their frequency and long-term course.

Agoraphobia and panic disorder There has been considerable debate recently as

to which of agoraphobia and panic disorder should be regarded as primary. From

an international and cross-cultural perspective, the amount and type of evidence

available does not appear to justify rejection of the still widely accepted notion

that the phobic disorder is best regarded as the prime disorder, with attacks of

panic usually indicating its severity.

Mixed categories of anxiety and depression Psychiatrists and others, especially

in developing countries, who see patients in primary health care services should

find particular use for F41.2 (mixed anxiety and depressivedisorder), F41.3 (other

mixed disorders), the various subdivisions of F43.2 (adjustment disorder), and

F44.7 (mixed dissociative [conversion] disorder). The purpose of these categories

is to facilitate the description of disorders manifest by a mixture of symptoms for

which a simpler and more traditional psychiatric label is not appropriate but

which nevertheless represent significantly common, severe states of distress and

interference with functioning. They also result in frequent referral to primary

care, medical and psychiatric services. Difficulties in using these categories

reliably may be encountered, but it is important to test them and - if necessary -

improve their definition.

Dissociative and somatoform disorders, in relation to hysteria The term

"hysteria" has notbeen used in the title for any disorder in Chapter V(F) of ICD-10

because of its many and varied shades of meaning. Instead, "dissociative" has

been preferred, to bring together disorders previously termed hysteria, of both

dissociative and conversion types. This is largely because patients with the

dissociative and conversion varieties often share a number of other

characteristics, and in addition they frequently exhibit both varieties at the same

or different times. It also seems reasonable to presume that the same (or very

similar) psychological mechanisms are common to both types of symptoms.

There appears to be widespread international acceptance of the usefulness of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-22-320.jpg)

![25

emotionally unstable personality disorder (F60.3), again in the hope of stimulating

investigations.

Other disorders of adult personality and behaviour (F68) Two categories that

have been included here but were not present in ICD-9 are F68.0, elaboration of

physicalsymptoms for psychologicalreasons, and F68.1, intentionalproduction or

feigning of symptoms or disabilities, either physical or psychological [factitious

disorder]. Since these are, strictly speaking, disorders of role or illness behaviour,

it should be convenient for psychiatrists to have them grouped with other

disorders of adult behaviour. Together with malingering (Z76.5), which has always

been outside Chapter V of the ICD, the disorders from a trio of diagnoses often

need to be considered together. The crucial difference between the first two and

malingering is that the motivation for malingering is obvious and usually confined

to situations where personal danger, criminal sentencing, or large sums of money

are involved.

Mental retardation (F70-F79) The policy for Chapter V(F) of ICD-10 has always

been to deal with mental retardation as briefly and as simply as possible,

acknowledging that justice can be done to this topic only by means of a

comprehensive, possibly multiaxial, system. Such a system needs to be developed

separately, and work to produce appropriate proposals for international use is

now in progress.

-21-

Disorders with onset specific to childhood F80-F89 Disorders of psychological

development Disorders of childhood such as infantile autism and disintegrative

psychosis, classified in ICD-9 as psychoses, are now more appropriately contained

in F84.-, pervasive developmental disorders. While some uncertainty remains

about their nosological status, it has been considered that sufficient information

is now available to justify the inclusion of the syndromes of Rett and Asperger in

this group as specified disorders. Overactive disorder associated with mental

retardation and stereotyped movements (F84.4) has been included in spite of its](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-25-320.jpg)

![28

-24-

List of categories

F00-F09 Organic,includingsymptomatic,mentaldisorders

F00 DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease F00.0DementiainAlzheimer'sdiseasewithearlyonset

F00.1DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease withlate onsetF00.2DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease,atypical or

mixedtype F00.9DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease,unspecified

F01VasculardementiaF01.0Vasculardementiaof acute onsetF01.1Multi-infarctdementia

F01.2Subcortical vasculardementiaF01.3Mixedcortical andsubcortical vasculardementiaF01.8Other

vasculardementiaF01.9Vasculardementia,unspecified

F02Dementiainotherdiseasesclassifiedelsewhere F02.0DementiainPick'sdisease F02.1Dementiain

Creutzfeldt-Jakobdisease F02.2DementiainHuntington'sdisease F02.3DementiainParkinson'sdisease

F02.4Dementiainhumanimmunodeficiencyvirus[HIV] diseaseF02.8Dementiainotherspecified

diseasesclassifiedelsewhere

F03Unspecifieddementia

A fifthcharactermay be addedto specifydementiainF00-F03,as follows:

.x0 Withoutadditional symptoms.x1Othersymptoms,predominantlydelusional .x2Othersymptoms,

predominantlyhallucinatory.x3Othersymptoms,predominantlydepressive .x4Othermixedsymptoms

F04Organic amnesicsyndrome,notinducedbyalcohol andothersubstances

F05Delirium,notinducedbyalcohol andotherpsychoactive substancesF05.0Delirium, not

superimposedondementia,sodescribedF05.1Delirium, superimposedondementiaF05.8Other

deliriumF05.9Delirium, unspecified

F06Other mental disordersdue tobraindamage anddysfunctionandtophysical disease F06.0Organic

hallucinosisF06.1Organiccatatonicdisorder

-25-

F06.2Organic delusional[schizophrenia-like]disorderF06.3Organicmood[affective] disorders .30

Organicmanic disorder .31 Organicbipolaraffective disorder .32 Organicdepressive disorder .33

OrganicmixedaffectivedisorderF06.4OrganicanxietydisorderF06.5Organicdissociative disorder

F06.6Organic emotionallylabile [asthenic] disorder F06.7Mildcognitive disorderF06.8Otherspecified

mental disordersdue tobraindamage anddysfunctionandtophysical disease F06.9Unspecifiedmental

disorderdue tobraindamage and dysfunctionandtophysical disease](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-28-320.jpg)

![29

F07Personalityandbehavioural disorderdue tobraindisease,damage anddysfunctionF07.0Organic

personalitydisorderF07.1PostencephaliticsyndromeF07.2Postconcussional syndrome F07.8Other

organicpersonalityandbehavioural disorder due tobraindisease,damage anddysfunction

F09Unspecifiedorganicorsymptomaticmental disorder

-26-

F10--F19 Mental andbehavioural disordersdue to psychoactive substance use

F10.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of alcohol

F11.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of opioids

F12.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of cannabinoids

F13.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of sedativesorhypnotics

F14.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of cocaine

F15.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of otherstimulants,includingcaffeine

F16.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of hallucinoeens

F17.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of tobacco

F18.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of volatile solvents

F19.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue tomultipledruguse anduse of otherpsychoactive

substances

Four- and five-charactercategoriesmaybe usedtospecifythe clinical conditions,asfollows:

F1x.0 Acute intoxication .00 Uncomplicated .01 Withtrauma or otherbodilyinjury .02 Withother

medical complications .03With delirium .04 Withperceptual distortions .05 Withcoma .06 With

convulsions .07Pathological intoxication

F1x.1 Harmful use

F1x.2 Dependence syndrome .20 Currentlyabstinent .21 Currentlyabstinent,butina protected

environment .22 Currentlyona clinicallysupervised maintenance orreplacementregime [controlled

dependence] .23 Currentlyabstinent,butreceivingtreatment withaversive orblockingdrugs .24

Currentlyusingthe substance [active

-27-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-29-320.jpg)

![30

dependence] .25 Continuoususe .26Episodicuse [dipsomania]

F1x.3 Withdrawal state .30 Uncomplicated .31With convulsions

F1x.4 Withdrawal state withdelirium .40Withoutconvulsions .41With convulsions

F1x.5 Psychoticdisorder .50 Schizophrenia-like .51 Predominantlydelusional .52 Predominantly

hallucinatory .53Predominantlypolymorphic .54 Predominantlydepressive symptoms .55

Predominantlymanicsymptoms .56Mixed

F1x.6 Amnesicsyndrome

F1x.7 Residual andlate-onsetpsychoticdisorder .70 Flashbacks .71 Personalityorbehaviourdisorder

.72 Residual affectivedisorder .73 Dementia .74 Otherpersistingcognitiveimpairment .75 Late-onset

psychoticdisorder

F1x.8 Othermental andbehavioural disorders

F1x.9 Unspecifiedmental andbehavioural disorder

-28-

F20-F29 Schizophrenia, schizotypal anddelusional disorders

F20 Schizophrenia F20.0 Paranoidschizophrenia F20.1 Hebephrenicschizophrenia F20.2 Catatonic

schizophrenia F20.3 Undifferentiatedschizophrenia F20.4 Post-schizophrenicdepression F20.5

Residual schizophrenia F20.6 Simple schizophrenia F20.8Other schizophrenia F20.9 Schizophrenia,

unspecified

A fifthcharactermay be usedto classifycourse:.x0Continuous.x1Episodicwithprogressive deficit.x2

Episodicwithstable deficit.x3Episodicremittent.x4Incomplete remission.x5Complete remission.x6

Other.x9 Course uncertain,periodof observationtooshort

F21 Schizotypal disorder

F22 Persistentdelusionaldisorders F22.0 Delusional disorder F22.8 Otherpersistentdelusional

disorders F22.9 Persistentdelusional disorder,unspecified

F23 Acute and transientpsychoticdisorders F23.0 Acute polymorphicpsychoticdisorderwithout

symptomsof schizophrenia F23.1Acute polymorphicpsychoticdisorderwithsymptomsof

schizophrenia F23.2 Acute schizophrenia-likepsychoticdisorder F23.3 Otheracute predominantly

delusionalpsychoticdisorders F23.8 Otheracute andtransientpsychoticdisorders F23.9Acute and

transientpsychoticdisordersunspecified](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-30-320.jpg)

![31

A fifthcharactermay be usedto identifythe presence orabsence of associatedacute stress:.x0Without

associatedacute stress.x1With associatedacute stress

-29-

F24 Induceddelusional disorder

F25 Schizoaffective disorders F25.0 Schizoaffectivedisorder,manictype F25.1 Schizoaffectivedisorder,

depressivetype F25.2 Schizoaffective disorder,mixedtype F25.8 Otherschizoaffective disorders F25.9

Schizoaffective disorder,unspecified

F28 Othernonorganicpsychoticdisorders

F29 Unspecifiednonorganicpsychosis

-30-

F30-F39 Mood [affective] disorders

Overviewof thisblock F30 Manic episode F30.0Hypomania F30.1 Mania withoutpsychoticsymptoms

F30.2 Mania withpsychoticsymptoms F30.8 Othermanicepisodes F30.9 Manic episode,unspecified

F31 Bipolaraffective disorder F31.0 Bipolaraffective disorder,currentepisode hypomanic F31.1 Bipolar

affective disorder,currentepisodemanicwithoutpsychoticsymptoms F31.2 Bipolaraffective disorder,

currentepisode manicwithpsychoticsymptoms F31.3Bipolaraffectivedisorder,currentepisode mild

or moderate depression .30 Withoutsomaticsyndrome .31 Withsomaticsyndrome F31.4 Bipolar

affective disorder,currentepisodesevere depressionwithoutpsychoticsymptoms F31.5 Bipolar

affective disorder,currentepisodesevere depressionwithpsychoticsymptoms F31.6 Bipolaraffective

disorder,currentepisodemixed F31.7 Bipolaraffectivedisorder,currentlyinremission F31.8Other

bipolaraffectivedisorders F31.9 Bipolaraffectivedisorder,unspecified

F32 Depressiveepisode F32.0 Milddepressive episode .00 Withoutsomaticsyndrome .01 With

somaticsyndrome F32.1 Moderate depressive episode .10 Without somaticsyndrome .11 With

somaticsyndrome F32.2 Severe depressive episode withoutpsychoticsymptoms F32.3 Severe

depressiveepisodewithpsychoticsymptoms F32.8Otherdepressive episodes F32.9 Depressive

episode,unspecified

-31-

F33 Recurrentdepressive disorder F33.0Recurrentdepressivedisorder,currentepisode mild .00

Withoutsomaticsyndrome .01 Withsomaticsyndrome F33.1 Recurrentdepressive disorder,current](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-31-320.jpg)

![32

episode moderate .10 Withoutsomaticsyndrome .11 With somaticsyndrome F33.2 Recurrent

depressivedisorder,currentepisode severewithoutpsychoticsymptoms F33.3 Recurrentdepressive

disorder,currentepisodesevere withpsychoticsymptoms F33.4 Recurrentdepressive disorder,

currentlyinremission F33.8Otherrecurrentdepressivedisorders F33.9 Recurrentdepressive disorder,

unspecified

F34 Persistentmood[affective] disorders F34.0Cyclothymia F34.1 Dysthymia F34.8 Otherpersistent

mood[affective] disorders F34.9Persistent mood[affective] disorder,unspecified F38 Othermood

[affective] disorders F38.0Othersingle mood[affective] disorders .00 Mixedaffectiveepisode F38.1

Otherrecurrentmood[affective] disorders .10 Recurrentbrief depressive disorder F38.8 Other

specifiedmood[affective] disorders

F39 Unspecifiedmood[affective] disorder

-32-

F40-F48 Neurotic,stress-relatedandsomatoformdisorders F40 Phobicanxietydisorders F40.0

Agoraphobia .00 Withoutpanicdisorder .01 Withpanic disorder F40.1 Social phobias F40.2 Specific

(isolated)phobias F40.8 Otherphobicanxietydisorders F40.9 Phobicanxietydisorder,unspecified

F41 Otheranxietydisorders F41.0 Panicdisorder[episodicparoxysmal anxiety] F41.1Generalized

anxietydisorder F41.2 Mixedanxietyanddepressivedisorder F41.3 Othermixedanxietydisorders

F41.8 Otherspecifiedanxietydisorders F41.9 Anxietydisorder,unspecified

F42 Obsessive- compulsive disorder F42.0 Predominantlyobsessionalthoughtsorruminations F42.1

Predominantlycompulsive acts[obsessionalrituals] F42.2 Mixedobsessional thoughtsandacts F42.8

Otherobsessive - compulsivedisorders F42.9 Obsessive - compulsive disorder,unspecified

F43 Reactiontosevere stress,andadjustmentdisorders F43.0Acute stressreaction F43.1 Post-

traumaticstressdisorder F43.2 Adjustmentdisorders .20 Brief depressive reaction .21 Prolonged

depressivereaction .22 Mixedanxietyanddepressive reaction .23 Withpredominantdisturbanceof

otheremotions .24 With predominantdisturbance of conduct .25 With mixeddisturbance of

emotionsandconduct .28 With otherspecifiedpredominantsymptoms F43.8Otherreactionsto

severe stress F43.9 Reactiontosevere stress,unspecified

F44 Dissociative [conversion] disorders F44.0Dissociative amnesia F44.1 Dissociative fugue F44.2

Dissociative stupor F44.3Trance and possessiondisorders F44.4 Dissociative motordisorders

-33-

F44.5 Dissociative convulsions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-32-320.jpg)

![33

F44.6 Dissociative anaesthesiaandsensoryloss F44.7 Mixeddissociative [conversion] disorders F44.8

Otherdissociative[conversion] disorders .80 Ganser's syndrome .81 Multiple personalitydisorder .82

Transientdissociative [conversion]disordersoccurringinchildhood and adolescence .88 Other

specifieddissociative [conversion]disorders F44.9 Dissociative[conversion] disorder,unspecified

F45 Somatoformdisorders F45.0Somatizationdisorder F45.1Undifferentiatedsomatoformdisorder

F45.2 Hypochondriacal disorder F45.3 Somatoformautonomicdysfunction .30 Heart and

cardiovascularsystem .31 Upper gastrointestinal tract .32 Lowergastrointestinaltract .33

Respiratorysystem .34 Genitourinarysystem .38 Otherorgan or system F45.4 Persistentsomatoform

paindisorder F45.8 Othersomatoformdisorders F45.9Somatoformdisorder,unspecified

F48 Otherneuroticdisorders F48.0 Neurasthenia F48.1 Depersonalization - derealizationsyndrome

F48.8 Otherspecifiedneuroticdisorders F48.9Neuroticdisorder,unspecified

-34-

F50-F59 Behavioural syndromesassociatedwithphysiological disturbancesandphysical factors F50

Eatingdisorders F50.0 Anorexianervosa F50.1 Atypical anorexianervosa F50.2 Bulimianervosa F50.3

Atypical bulimianervosa F50.4 Overeatingassociated withotherpsychological disturbances F50.5

Vomitingassociatedwithotherpsychological disturbances F50.8Othereatingdisorders F50.9 Eating

disorder,unspecified

F51 Nonorganicsleepdisorders F51.0Nonorganicinsomnia F51.1 Nonorganichypersomnia F51.2

Nonorganicdisorderof the sleep-wake schedule F51.3 Sleepwalking[somnambulism] F51.4 Sleep

terrors[nightterrors] F51.5 Nightmares F51.8 Othernonorganicsleepdisorders F51.9 Nonorganic

sleepdisorder,unspecified

F52 Sexual dysfunction,notcausedbyorganicdisorderordisease F52.0 Lack or lossof sexual desire

F52.1 Sexual aversionandlackof sexual enjoyment .10 Sexual aversion .11 Lack of sexual enjoyment

F52.2 Failure of genital response F52.3 Orgasmicdysfunction F52.4Premature ejaculation F52.5

Nonorganicvaginismus F52.6 Nonorganicdyspareunia F52.7 Excessive sexual drive F52.8 Othersexual

dysfunction,notcausedbyorganicdisordersordisease F52.9 Unspecifiedsexual dysfunction,not

causedby organicdisorderordisease F53Mental and behavioural disordersassociatedwiththe

puerperium, notelsewhereclassified F53.0Mild mental andbehavioural disordersassociatedwiththe

puerperium, notelsewhereclassified

-35-

F53.1 Severe mental andbehavioural disordersassociatedwiththe puerperium, notelsewhere

classified F53.8 Othermental andbehavioural disordersassociatedwiththe puerperium, notelsewhere

classified F53.9 Puerperal mental disorder,unspecified](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-33-320.jpg)

![34

F54Psychological andbehavioural factorsassociatedwithdisordersordiseasesclassifiedelsewhere

F55 Abuse of non-dependence-producingsubstances F55.0 Antidepressants F55.1 Laxatives F55.2

Analgesics F55.3 Antacids F55.4 Vitamins F55.5 Steroidsorhormones F55.6 Specificherbal orfolk

remedies F55.8Othersubstancesthatdo not produce dependence F55.9Unspecified

F59Unspecifiedbehavioural syndromesassociatedwithphysiological disturbancesandphysical factors

-36-

F60-F69 Disordersof adultpersonalityandbehaviour

F60 Specificpersonalitydisorders F60.0 Paranoidpersonalitydisorder F60.1 Schizoidpersonality

disorder F60.2 Dissocial personalitydisorder F60.3 Emotionallyunstable personalitydisorder .30

Impulsive type .31 Borderline type F60.4Histrionicpersonalitydisorder F60.5 Anankasticpersonality

disorder F60.6 Anxious[avoidant]personalitydisorder F60.7 Dependentpersonalitydisorder F60.8

Otherspecificpersonalitydisorders F60.9 Personalitydisorder,unspecified

F61 Mixedandotherpersonalitydisorders F61.0 Mixedpersonalitydisorders F61.1Troublesome

personalitychanges

F62 Enduringpersonalitychanges,notattributabletobraindamage anddisease F62.0 Enduring

personalitychange aftercatastrophicexperience F62.1 Enduringpersonalitychange afterpsychiatric

illness F62.8Otherenduringpersonalitychanges F62.9Enduringpersonalitychange,unspecified

F63 Habitand impulse disorders F63.0 Pathological gambling F63.1Pathological fire-setting

[pyromania] F63.2 Pathological stealing[kleptomania] F63.3 Trichotillomania F63.8 Otherhabitand

impulse disorders F63.9Habit and impulse disorder,unspecified

F64 Genderidentitydisorders F64.0 Transsexualism F64.1 Dual-role transvestism F64.2 Gender

identitydisorderof childhood F64.8 Othergenderidentitydisorders F64.9 Genderidentitydisorder,

unspecified

F65 Disordersof sexual preference F65.0 Fetishism F65.1 Fetishistictransvestism F65.2Exhibitionism

F65.3 Voyeurism F65.4Paedophilia

-37-

F65.5 Sadomasochism F65.6 Multiple disordersof sexual preference F65.8Otherdisordersof sexual

preference F65.9Disorderof sexual preference,unspecified

F66 Psychological andbehavioural disordersassociatedwithsexual developmentandorientation F66.0

Sexual maturationdisorder F66.1 Egodystonicsexual orientation F66.2Sexual relationshipdisorder](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-34-320.jpg)

![35

F66.8 Otherpsychosexual developmentdisorders F66.9 Psychosexual developmentdisorder,

unspecified

A fifthcharactermay be usedto indicate associationwith:.x0Heterosexuality.x1Homosexuality.x2

Bisexuality.x8Other,includingprepubertal

F68 Otherdisordersof adultpersonalityandbehaviour F68.0 Elaborationof physical symptomsfor

psychological reasons F68.1 Intentional productionorfeigningof symptomsordisabilities,either

physical orpsychological [factitiousdisorder] F68.8 Otherspecifieddisordersof adultpersonalityand

behaviour

F69 Unspecifieddisorderof adultpersonalityandbehaviour

-38-

F70-F79 Mental retardation

F70 Mildmental retardation

F71 Moderate mental retardation

F72 Severe mental retardation

F73 Profoundmental retardation

F78 Othermental retardation

F79 Unspecifiedmental retardation

A fourthcharacter maybe usedto specifythe extentof associatedbehavioural impairment:

F7x.0 No,or minimal,impairmentof behaviour F7x.1Significantimpairmentof behaviourrequiring

attentionortreatment F7x.8 Otherimpairmentsof behaviour F7x.9Withoutmentionof impairmentof

behaviour

-39-

F80-F89 Disordersof psychological development

F80 Specificdevelopmental disordersof speechandlanguage F80.0 Specificspeecharticulation

disorder F80.1 Expressivelanguage disorder F80.2 Receptive languagedisorder F80.3 Acquiredaphasia

withepilepsy[Landau-Kleffnersyndrome] F80.8 Otherdevelopmentaldisordersof speechandlanguage

F80.9 Developmental disorderof speechandlanguage,unspecified F81 Specificdevelopmental

disordersof scholasticskills F81.0 Specificreadingdisorder F81.1Specificspellingdisorder F81.2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-35-320.jpg)

![36

Specificdisorderof arithmetical skills F81.3 Mixeddisorderof scholasticskills F81.8 Other

developmental disordersof scholasticskills F81.9 Developmentaldisorderof scholasticskills,

unspecified F82Specificdevelopmental disorderof motorfunction F83 Mixedspecificdevelopmental

disorders

F84 Pervasive developmental disorders F84.0Childhoodautism F84.1 Atypical autism F84.2 Rett's

syndrome F84.3 Otherchildhooddisintegrative disorder F84.4Overactive disorderassociatedwith

mental retardationand stereotypedmovements F84.5 Asperger'ssyndrome F84.8Otherpervasive

developmental disorders F84.9Pervasive developmentaldisorder,unspecified F88Otherdisordersof

psychological development

F89 Unspecifieddisorderof psychological development

-40-

F90-F98 Behavioural andemotionaldisorderswithonsetusuallyoccurringinchildhoodandadolescence

F90 Hyperkineticdisorders F90.0 Disturbance of activityandattention F90.1 Hyperkineticconduct

disorder F90.8 Otherhyperkineticdisorders F90.9 Hyperkineticdisorder,unspecified F91 Conduct

disorders F91.0 Conductdisorderconfinedtothe familycontext F91.1 Unsocializedconductdisorder

F91.2 Socializedconductdisorder F91.3 Oppositionaldefiantdisorder F91.8 Otherconductdisorders

F91.9 Conductdisorder,unspecified F92Mixeddisordersof conductandemotions F92.0 Depressive

conduct disorder F92.8 Othermixeddisordersof conductandemotions F92.9Mixeddisorderof

conduct andemotions,unspecified F93 Emotional disorderswithonsetspecifictochildhood F93.0

Separationanxietydisorderof childhood F93.1Phobicanxietydisorderof childhood F93.2 Social

anxietydisorderof childhood F93.3Siblingrivalrydisorder F93.8 Otherchildhoodemotional disorders

F93.9 Childhoodemotionaldisorder,unspecified F94Disordersof social functioningwithonsetspecific

to childhoodandadolescence F94.0 Elective mutism F94.1 Reactive attachmentdisorderof childhood

F94.2 Disinhibitedattachmentdisorderof childhood F94.8 Otherchildhooddisordersof social

functioning F94.9 Childhooddisorderof social functioning,unspecified F95Tic disorders F95.0

Transientticdisorder F95.1 Chronicmotoror vocal ticdisorder F95.2 Combinedvocal andmultiple

motor ticdisorder[de laTourette's syndrome] F95.8 Othertic disorders F95.9 Tic disorder,

unspecified

-41-

F98 Otherbehavioural andemotional disorderswithonsetusually occurringinchildhoodand

adolescence F98.0Nonorganicenuresis F98.1Nonorganicencopresis F98.2Feedingdisorderof infancy

and childhood F98.3 Picaof infancyandchildhood F98.4 Stereotypedmovementdisorders F98.5

Stuttering[stammering] F98.6 Cluttering F98.8Otherspecifiedbehavioural andemotionaldisorders](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-36-320.jpg)

![37

withonset usuallyoccurringinchildhoodandadolescence F98.9Unspecifiedbehaviouralandemotional

disorderswithonsetusuallyoccurringinchildhoodandadolescence

F99 Unspecifiedmental disorder

F99 Mental disorder,nototherwise specified

-42-

Clinical descriptions

and

diagnosticguidelines

-43-

F00-F09 Organic,includingsymptomatic,mentaldisorders

Overviewof thisblock

F00 DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease F00.0DementiainAlzheimer'sdiseasewithearlyonset

F00.1DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease withlate onsetF00.2DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease,atypical or

mixed type F00.9DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease,unspecified

F01VasculardementiaF01.0Vasculardementiaof acute onsetF01.1Multi-infarctdementia

F01.2Subcortical vasculardementiaF01.3Mixedcortical andsubcortical vasculardementiaF01.8Other

vasculardementiaF01.9Vasculardementia, unspecified

F02Dementiainotherdiseasesclassifiedelsewhere F02.0DementiainPick'sdisease F02.1Dementiain

Creutzfeldt-Jakobdisease F02.2DementiainHuntington'sdisease F02.3DementiainParkinson'sdisease

F02.4Dementiainhumanimmunodeficiency virus[HIV] disease F02.8Dementiainotherspecified

diseasesclassified elsewhere

F03Unspecifieddementia

A fifthcharactermay be addedto specifydementiainF00-F03,as`follows: .x0Withoutadditional

symptoms .x1Othersymptoms,predominantlydelusional .x2Othersymptoms,predominantly

hallucinatory .x3Othersymptoms,predominantlydepressive .x4Othermixedsymptoms

F04Organic amnesicsyndrome,notinducedbyalcohol andother psychoactive substances](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-37-320.jpg)

![38

F05Delirium,notinducedbyalcohol andotherpsychoactive substancesF05.0Delirium, not

superimposedondementia,sodescribedF05.1Delirium, superimposedondementiaF05.8Other

deliriumF05.9Delirium, unspecified

F06Other mental disordersdue tobraindamage anddysfunction andtophysical disease F06.0Organic

hallucinosisF06.1OrganiccatatonicdisorderF06.2Organicdelusional [schizophrenia-like] disorder

-44-

F06.3Organic mood[affective]disorders.30Organicmanic disorder.31 Organicbipolardisorder.32

Organicdepressive disorder.33 Organicmixedaffective disorderF06.4Organicanxietydisorder

F06.5Organic dissociative disorderF06.6Organicemotionallylabile[asthenic] disorder F06.7Mild

cognitive disorderF06.8Otherspecifiedmentaldisordersdue tobraindamage anddysfunctionandto

physical disease F06.9Unspecifiedmentaldisorderdue tobraindamage and dysfunctionandto

physical disease

F07Personalityandbehavioural disordersdue tobraindisease,damage anddysfunctionF07.0Organic

personalitydisorderF07.1PostencephaliticsyndromeF07.2Postconcussional syndrome F07.8Other

organicpersonalityandbehavioural disorder due tobraindisease,damage anddysfunctionF07.9

Unspecifiedorganicpersonalityandbehavioural disordersdue tobraindisease, damage anddysfunction

F09Unspecifiedorganicorsymptomaticmental disorder

-45-

Introduction

Thisblockcomprises`arange of mental disordersgroupedtogetheronthe basisof theircommon,

demonstrable etiologyincerebral disease,braininjury,orotherinsultleadingtocerebral dysfunction.

The dysfunctionmaybe primary,as indiseases,injuries,andinsultsthataffectthe braindirectlyorwith

predilection;orsecondary,asinsystemicdiseasesanddisordersthatattackthe brainonlyas one of the

multiple organsorsystemsof the bodyinvolved.Alcohol-anddrug-causedbraindisorders,though

logicallybelongingtothisgroup,are classifiedunderF10-F19 because of practical advantagesinkeeping

all disordersdue topsychoactive substance use inasingle block.

Althoughthe spectrumof psychopathological manifestationsof the conditionsincludedhere isbroad,

the essential featuresof the disordersformtwomainclusters.Onthe one hand,there are syndromesin

whichthe invariable andmostprominentfeaturesare eitherdisturbancesof cognitive functions,suchas

memory,intellect,andlearning,ordisturbancesof the sensorium, suchasdisordersof consciousness

and attention.Onthe otherhand,there are syndromesof whichthe mostconspicuousmanifestations

are inthe areas of perception(hallucinations),thoughtcontents(delusions),ormoodand emotion](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-38-320.jpg)

![43

F00.2 DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease,atypical ormixedtype Dementiasthatdonot fitthe

descriptionsandguidelinesforeitherF00.0or F00.1 shouldbe classifiedhere;mixedAlzheimer'sand

vasculardementiasare alsoincludedhere.

F00.9 DementiainAlzheimer'sdisease,unspecified

-50-

F01 Vasculardementia

Vascular(formerlyarteriosclerotic) dementia,whichincludesmulti-infarctdementia,isdistinguished

fromdementiainAlzheimer'sdisease byitshistoryof onset,clinical features,andsubsequentcourse.

Typically,there isahistoryof transientischaemicattackswithbrief impairmentof consciousness,

fleetingpareses,orvisual loss.The dementiamayalsofollow asuccessionof acute cerebrovascular

accidentsor,lesscommonly,asingle majorstroke.Some impairmentof memoryandthinkingthen

becomesapparent.Onset,whichisusuallyinlaterlife,canbe abrupt,followingone particularischaemic

episode,orthere maybe more gradual emergence.The dementiaisusuallythe resultof infarctionof

the braindue tovascular diseases,includinghypertensive cerebrovasculardisease.The infarctsare

usuallysmall butcumulativeintheireffect.

Diagnosticguidelines

The diagnosispresupposesthe presence of adementiaasdescribedabove.Impairmentof cognitive

functioniscommonlyuneven,sothatthere maybe memoryloss,intellectualimpairment,andfocal

neurological signs.Insightandjudgementmaybe relativelywell preserved.Anabruptonsetora

stepwise deterioration,aswell asthe presence of focal neurological signsandsymptoms,increasesthe

probabilityof the diagnosis;insome cases,confirmationcanbe providedonlybycomputerizedaxial

tomographyor,ultimately,neuropathological examination.

Associatedfeaturesare:hypertension,carotidbruit,emotionallabilitywithtransientdepressive mood,

weepingorexplosive laughter,andtransientepisodesof cloudedconsciousnessordelirium,often

provokedbyfurtherinfarction.Personalityisbelievedtobe relativelywell preserved,but personality

changesmay be evidentinaproportionof caseswithapathy,disinhibition,oraccentuationof previous

traitssuch as egocentricity,paranoidattitudes,orirritability.

Includes:arterioscleroticdementia

Differential diagnosis.Consider: delirium(F05.-);otherdementia,particularlyinAlzheimer'sdisease

(F00.-);mood[affective] disorders(F30-F39);mildormoderate mental retardation(F70-F71);subdural

haemorrhage (traumatic(S06.5),nontraumatic(162.0)).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-43-320.jpg)

![46

F02.2 DementiainHuntington'sdisease A dementiaoccurringaspartof a widespreaddegenerationof

the brain.Huntington'sdisease istransmittedbyasingle autosomal dominantgene.Symptomstypically

emerge inthe thirdand fourthdecade,andthe sex incidence isprobablyequal.Inaproportionof cases,

the earliestsymptomsmaybe depression,anxiety,orfrankparanoidillness,accompaniedbya

personalitychange.Progressionisslow,leadingto deathusuallywithin10to 15 years.

-53-

Diagnosticguidelines

The associationof choreiformmovementdisorder,dementia,andfamilyhistoryof Huntington'sdisease

ishighlysuggestiveof the diagnosis,thoughsporadiccasesundoubtedlyoccur.

Involuntarychoreiformmovements,typicallyof the face,hands,andshoulders,orinthe gait,are early

manifestations.Theyusuallyprecede the dementiaandonlyrarelyremainabsentuntilthe dementiais

veryadvanced.Othermotorphenomenamaypredominate whenthe onsetisatan unusuallyyoungage

(e.g.striatal rigidity)orat a late age (e.g.intentiontremor).

The dementiaischaracterizedbythe predominantinvolvementof frontal lobe functionsinthe early

stage,withrelative preservationof memoryuntillater.

Includes:dementiainHuntington'schorea

Differential diagnosis.Consider:othercasesof choreicmovements;Alzheimer's,Pick'sorCreutzfeldt-

Jakobdisease (F00.-,F02.0, F02.1).

F02.3 DementiainParkinson'sdisease A dementiadevelopinginthe course of establishedParkinson's

disease (especiallyitssevereforms).Noparticulardistinguishingclinicalfeatureshave yetbeen

demonstrated.The dementiamaybe differentfromthatineitherAlzheimer'sdiseaseorvascular

dementia;however,there isalsoevidence thatitmaybe the manifestationof aco-occurrence of one of

these conditionswithParkinson'sdisease.Thisjustifiesthe identificationof casesof Parkinson'sdisease

withdementiaforresearchuntil the issueisresolved.

Diagnosticguidelines

Dementiadevelopinginanindividualwithadvanced,usuallysevere,Parkinson'sdisease.

Includes:dementiainparalysisagitans dementiainparkinsonism Differential diagnosis.Consider:

othersecondarydementias(F02.8);multi-infarctdementia(F01.1) associatedwithhypertensiveor

diabeticvasculardisease;braintumor(C70-C72);normal pressure hydrocephalus(G91.2).

F02.4 Dementiainhumanimmunodeficiencyvirus[HIV] disease A disordercharacterizedbycognitive

deficitsmeetingthe clinical diagnosticcriteriafordementia,inthe absenceof aconcurrentillnessor

condition otherthanHIV infectionthatcouldexplainthe findings.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-46-320.jpg)

![47

HIV dementiatypicallypresentswithcomplaintsof forgetfulness,slowness,poorconcentration,and

difficultieswithproblem-solvingandreading.Apathy,reducedspontaneity,andsocial withdrawal are

common,and ina significantminorityof

-54-

affectedindividualsthe illnessmaypresentatypicallyasanaffective disorder,psychosis,orseizures.

Physical examinationoftenrevealstremor,impairedrapidrepetitive movements,imbalance,ataxia,

hypertonia,generalizedhyperreflexia,positivefrontal releasesigns,andimpairedpursuitandsaccadic

eye movements.

ChildrenalsodevelopanHIV-associatedneurodevelopmental disordercharacterizedbydevelopmental

delay,hypertonia,microcephaly,andbasal gangliacalcification.The neurological involvementmost

oftenoccursin the absence of opportunisticinfectionsandneoplasms,whichisnotthe case foradults.

HIV dementiagenerally,butnotinvariably,progressesquickly(overweeksormonths) tosevere global

dementia,mutism,anddeath.

Includes:AIDS-dementiacomplex HIV encephalopathyorsubacute encephalitis

F02.8 Dementiainotherspecifieddiseasesclassifiedelsewhere Dementiacanoccur as a manifestation

or consequence of avarietyof cerebral andsomaticconditions.Tospecifythe etiology,the ICD-10code

for the underlyingconditionshouldbe added.

Parkinsonism-dementiacomplex of Guamshouldalsobe codedhere (identifiedbyafifthcharacter,if

necessary).Itisa rapidlyprogressingdementiafollowedbyextrapyramidal dysfunctionand,insome

cases,amyotrophiclateral sclerosis.The disease wasoriginallydescribedonthe islandof Guamwhere it

occurs withhighfrequencyinthe indigenouspopulation,affectingtwice asmanymalesasfemales;itis

nowknownto occur alsoin PapuaNewGuineaandJapan.

Includes:dementiain: carbon monoxide poisoning(T58) cerebral lipidosis(E75.-) epilepsy(G40.-)

general paralysisof the insane (A52.1) hepatolenticulardegeneration(Wilson'sdisease) (E83.0)

hypercalcaemia(E83.5) hypothyroidism, acquired(E00.-,E02) intoxications(T36-T65) multiple

sclerosis(G35) neurosyphilis(A52.1) niacindeficiency[pellagra] (E52) polyarteritisnodosa(M30.0)

systemiclupuserythematosus(M32.-) trypanosomiasis(AfricanB56.-,AmericanB57.-) vitaminB12

deficiency(E53.8)

F03 Unspecifieddementia

-55-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-47-320.jpg)

![50

Includes:acute brainsyndrome acute confusional state (nonalcoholic) acute infective psychosis

acute organic reaction acute psycho-organicsyndrome

Differential diagnosis.Deliriumshouldbe distinguishedfromotherorganicsyndromes,especially

dementia(F00-F03),fromacute and transientpsychoticdisorders(F23.-),andfromacute statesin

schizophrenia(F20.-) ormood[affective] disorders(F30-F39) inwhichconfusionalfeaturesmaybe

present.Delirium, inducedbyalcohol andotherpsychoactivesubstances,shouldbe codedinthe

appropriate section(F1x.4).

F05.0 Delirium,notsuperimposedondementia,sodescribedThiscode shouldbe usedfordelirium

that isnot superimposeduponpre-existingdementia.

F05.1 Delirium,superimposedondementiaThiscode shouldbe usedforconditionsmeetingthe above

criteriabutdevelopinginthe course of a dementia(F00-F03).

F05.8 Otherdelirium

Includes:deliriumof mixedorigin subacute confusional state ordelirium

F05.9 Delirium,unspecified

-58-

F06 Othermental disordersdue tobraindamage anddysfunctionandtophysical disease

Thiscategoryincludesmiscellaneousconditionscausallyrelatedtobraindysfunctiondue toprimary

cerebral disease,tosystemicdisease affectingthe brainsecondarily,toendocrine disorderssuchas

Cushing'ssyndrome orothersomaticillnesses,andtosome exogenoustoxicsubstances(butexcluding

alcohol anddrugs classifiedunderF10-F19) or hormones.These conditionshave incommonclinical

featuresthatdo notby themselvesallow apresumptivediagnosisof anorganicmental disorder,suchas

dementiaordelirium.Rather,the clinicalmanifestationsresemble,orare identical with,thoseof

disordersnotregardedas"organic"in the specificsense restrictedtothisblockof the classification.

Theirinclusionhere isbasedonthe hypothesisthattheyare directlycausedbycerebral diseaseor

dysfunctionratherthanresultingfromeitherafortuitousassociationwithsuchdiseaseordysfunction,

or a psychological reactiontoitssymptoms,suchasschizophrenia-likedisordersassociatedwithlong-

standingepilepsy.

The decisiontoclassifyaclinical syndrome here issupportedbythe following:

(a)evidence of cerebral disease,damage ordysfunctionorof systemicphysical disease,knowntobe

associatedwithone of the listedsyndromes;(b)atemporal relationship(weeksorafew months)

betweenthe developmentof the underlyingdiseaseandthe onsetof the mental syndrome;(c)recovery

fromthe mental disorderfollowingremoval orimprovementof the underlyingpresumedcause;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-50-320.jpg)

![52

The general criteriaforassumingorganicetiology,laiddowninthe introductiontoF06, mustbe met.In

addition,there shouldbe one of the following:

(a)stupor(diminutionorcomplete absence of spontaneousmovementwithpartial orcomplete mutism,

negativism, andrigidposturing); (b)excitement(grosshypermotilitywithorwithoutatendencyto

assaultiveness);(c)both(shiftingrapidlyandunpredictablyfromhypo- tohyperactivity).

Othercatatonic phenomenathat increase confidence inthe diagnosisare:stereotypies,waxyflexibility,

and impulsive acts.

Excludes:catatonicschizophrenia(20.2) dissociativestupor(F44.2) stuporNOS (R40.1)

F06.2 Organicdelusional [schizophrenia-like] disorderA disorderinwhichpersistentorrecurrent

delusionsdominate the clinical picture.The delusionsmaybe accompaniedbyhallucinationsbutare not

confinedtotheircontent.Featuressuggestive of schizophrenia,suchasbizarre delusions,hallucinations,

or thoughtdisorder,mayalsobe present.

Diagnosticguidelines

-60-

The general criteriaforassuminganorganic etiology,laiddowninthe introductiontoF06, mustbe met.

In addition,there shouldbe delusions(persecutory,of bodilychange,jealousy, disease,ordeathof the

subjector anotherperson).Hallucinations,thoughtdisorder,orisolatedcatatonicphenomenamaybe

present.Consciousnessandmemorymustnotbe affected.Thisdiagnosisshouldnotbe made if the

presumedevidenceof organiccausationisnonspecificorlimitedtofindingssuchasenlargedcerebral

ventricles(visualizedoncomputerizedaxial tomography) or"soft"neurological signs.

Includes:paranoidandparanoid-hallucinatoryorganicstates schizophrenia-likepsychosisinepilepsy

Excludes:acute andtransientpsychoticdisorders(F23.-) drug-inducedpsychoticdisorders(F1x.5)

persistentdelusionaldisorder(F22.-) schizophrenia(F20.-)

F06.3 Organicmood [affective] disordersDisorderscharacterizedbyachange inmood or affect,

usuallyaccompaniedbyachange in the overall level of activity.The onlycriterionforinclusionof these

disordersinthisblockistheirpresumeddirectcausationbyacerebral orother physical disorderwhose

presence musteitherbe demonstratedindependently(e.g.bymeansof appropriate physical and

laboratoryinvestigations) orassumedonthe basisof adequate historyinformation.The affective

disordermustfollowthe presumedorganicfactorandbe judgednotto representanemotional

response tothe patient'sknowledge of having,orhavingthe symptomsof,aconcurrentbrain disorder.

Postinfective depression(e.g.followinginfluenza)isacommonexample andshouldbe codedhere.

Persistentmildeuphorianotamountingtohypomania(whichissometimesseen,forinstance,in

associationwithsteroidtherapyorantidepressants) shouldnotbe codedhere butunderF06.8.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-52-320.jpg)

![53

Diagnosticguidelines

In additiontothe general criteriaforassumingorganicetiology,laiddowninthe introductiontoF06,the

conditionmustmeetthe requirementsforadiagnosisof one of the disorderslistedunderF30-F33.

Excludes:mood[affective] disorders,nonorganicor unspecified(F30- F39) righthemispheric

affective disorder(F07.8)

The followingfive-charactercodesmightbe usedtospecifythe clinical disorder:

F06.30 OrganicmanicdisorderF06.31 Organicbipolaraffective disorderF06.32 Organic depressive

disorderF06.33 Organicmixedaffective disorder

-61-

F06.4 OrganicanxietydisorderA disordercharacterizedbythe essential descriptive featuresof a

generalizedanxietydisorder(41.1),apanic disorder(F41.0),ora combinationof both,butarisingasa

consequence of anorganicdisordercapable of causingcerebral dysfunction(e.g.temporal lobe

epilepsy,thyrotoxicosis,orphaechromocytoma).

Excludes:anxietydisorders,nonorganicorunspecified(F41.-)

F06.5 Organicdissociative disorderA disorderthatmeetsthe requirementsforone of the disordersin

F44.- (dissociative [conversion] disorder) andforwhichthe general criteriafororganicetiologyare also

fulfilled(asdescribedinthe introductiontothisblock).

Excludes:dissociative[conversion] disorders,nonorganicor unspecified(F44.-)

F06.6 Organicemotionallylabile [asthenic] disorderA disordercharacterizedbymarkedandpersistent

emotional incontinence orlability,fatiguability,ora varietyof unpleasantphysicalsensations(e.g.

dizziness)andpainsregardedasbeingdue tothe presence of anorganic disorder.Thisdisorderis

thoughtto occur in associationwithcerebrovasculardiseaseorhypertensionmore oftenthanwith

othercauses.

Excludes:somatoformdisorders,nonorganicorunspecified (F45.-)

F06.7 Mildcognitive disorderThisdisordermayprecede,accompany,orfollow awide varietyof

infectionsandphysical disorders,bothcerebral andsystemic(includingHIV infection).Direct

neurological evidence of cerebral involvementisnotnecessarilypresent,butthere mayneverthelessbe

distressandinterference withusual activities.The boundariesof thiscategoryare still tobe firmly

established.Whenassociatedwithaphysical disorderfromwhichthe patientrecovers,mildcognitive

disorderdoesnotlastfor more thana few additional weeks.Thisdiagnosisshouldnotbe made if the

conditionisclearlyattributable toamental or behavioural disorderclassifiedinanyof the remaining

blocksinthisbook.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-53-320.jpg)

![57

-65-

F10-F19 Mental and behavioural disordersdue topsychoactivesubstance use

Overviewof thisblock

F10.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of alcohol F11.-Mental andbehavioural disordersdue

to use of opioidsF12.-Mental andbehavioural disordersdue touse of cannabinoidsF13.-Mental and

behavioural disordersdue touse of sedativesorhypnoticsF14.-Mental andbehavioural disordersdue to

use of cocaine F15.-Mental andbehavioural disordersdue touse of otherstimulants,includingcaffeine

F16.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of hallucinogensF17.-Mental and behavioural

disordersdue touse of tobacco F18.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue touse of volatile solvents

F19.-Mental and behavioural disordersdue tomultipledruguse anduse of otherpsychoactive

substances

Four- and five-charactercodesmaybe usedtospecifythe clinical conditions,asfollows:

F1x.0 Acute intoxication .00 Uncomplicated.01With trauma or otherbodilyinjury.02Withother

medical complications.03Withdelirium.04With perceptual distortions.05Withcoma .06 With

convulsions.07Pathological intoxication

F1x.1 Harmful use

F1x.2 Dependence syndrome .20 Currentlyabstinent.21Currentlyabstinent,butinaprotected

environment.22Currentlyona clinicallysupervisedmaintenanceor replacementregime [controlled

dependence] .23 Currentlyabstinent,butreceivingtreatmentwith aversive orblockingdrugs .24

Currentlyusingthe substance [active dependence].25Continuoususe .26 Episodicuse [dipsomania]

F1x.3 Withdrawal state .30 Uncomplicated.31 Withconvulsions

-66-

F1x.4 Withdrawal state withdelirium .40Withoutconvulsions.41Withconvulsions

F1x.5 Psychoticdisorder .50 Schizophrenia-like .51Predominantlydelusional.52Predominantly

hallucinatory.53Predominantlypolymorphic.54 Predominantlydepressive symptoms.55

Predominantlymanicsymptoms.56Mixed

F1x.6 Amnesicsyndrome

F1x.7 Residual andlate-onsetpsychoticdisorder.70 Flashbacks.71 Personalityorbehaviourdisorder.72

Residual affective disorder.73 Dementia.74Otherpersistingcognitive impairment.75Late-onset

psychoticdisorder](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-57-320.jpg)

![61

continue takingdrugs. The dependence syndrome maybe presentfora specificsubstance (e.g.

tobacco or diazepam),foraclass of substances(e.g.opioiddrugs),orfora wider

-71-

range of differentsubstances(asforthose individualswhofeel asense of compulsionregularlytouse

whateverdrugsare available andwhoshow distress,agitation,and/orphysical signsof awithdrawal

state uponabstinence).

Includes:chronicalcoholism dipsomania drugaddiction The diagnosisof the dependence syndrome

may be furtherspecifiedbythe followingfive-charactercodes:

F1x.20 Currentlyabstinent F1x.21 Currentlyabstinent,butinaprotectedenvironment(e.g.inhospital,

ina therapeuticcommunity,inprison,etc.) F1x.22 Currentlyona clinicallysupervisedmaintenance

or replacementregime[controlleddependence] (e.g.withmethadone;nicotinegumornicotine patch)

F1x.23 Currentlyabstinent,butreceivingtreatmentwithaversiveorblockingdrugs (e.g.naltrexone or

disulfiram) F1x.24 Currentlyusingthe substance [active dependence] F1x.25 Continuoususe

F1x.26 Episodicuse [dipsomania] F1.3 Withdrawal state A groupof symptomsof variable clustering

and severityoccurringonabsolute orrelative withdrawal of asubstance afterrepeated,andusually

prolongedand/orhigh-dose,use of thatsubstance.Onsetandcourse of the withdrawal state are time-

limitedandare relatedtothe type of substance andthe dose beingusedimmediatelybefore

abstinence.The withdrawal state maybe complicatedbyconvulsions. Diagnosticguidelines

Withdrawal state isone of the indicatorsof dependence syndrome (see F1x.2) andthislatterdiagnosis

shouldalsobe considered. Withdrawal state shouldbe codedasthe maindiagnosisif itisthe reason

for referral andsufficientlysevere to require medical attentioninitsownright. Physical symptoms

vary accordingto the substance beingused.Psychological disturbances(e.g.anxiety,depression,and

sleepdisorders) are also

-72-

commonfeaturesof withdrawal.Typically,the patientislikelytoreportthatwithdrawal symptomsare

relievedbyfurthersubstance use.

It shouldbe rememberedthatwithdrawalsymptomscanbe inducedbyconditioned/learnedstimuliin

the absence of immediatelyprecedingsubstance use.Insuchcasesa diagnosisof withdrawalstate

shouldbe made onlyif itis warrantedintermsof severity. Differential diagnosis.Manysymptoms

presentindrugwithdrawal state mayalsobe causedby otherpsychiatricconditions,e.g.anxietystates

and depressive disorders.Simple "hangover"ortremordue to otherconditionsshouldnotbe confused

withthe symptomsof a withdrawal state. The diagnosisof withdrawal state maybe furtherspecified

by usingthe followingfive-charactercodes: F1x.30 Uncomplicated](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-61-320.jpg)

![63

cocaine psychoses).Falsediagnosisinsuchcasesmayhave distressingandcostlyimplicationsforthe

patientandfor the healthservices. Includes:alcoholichallucinosis alcoholicjealousy alcoholic

paranoia alcoholicpsychosisNOS Differential diagnosis.Considerthe possibilityof anothermental

disorderbeingaggravatedorprecipitatedbypsychoactive substance use (e.g.schizophrenia(F20.-);

mood[affective] disorder(F30-F39);paranoidorschizoidpersonalitydisorder(F60.0,F60.1)).In such

cases,a diagnosisof psychoactive substance-inducedpsychoticstate maybe inappropriate.

-74-

The diagnosisof psychoticstate maybe furtherspecifiedbythe followingfive-charactercodes:

F1x.50 Schizophrenia-like F1x.51 Predominantlydelusional F1x.52 Predominantlyhallucinatory

(includesalcoholichallucinosis) F1x.53 Predominantlypolymorphic F1x.54 Predominantly

depressivesymptoms F1x.55 Predominantlymanicsymptoms F1x.56 Mixed F1x.6 Amnesic

syndrome A syndrome associatedwithchronicprominentimpairmentof recentmemory;remote

memoryissometimesimpaired,while immediaterecall ispreserved.Disturbancesof time sense and

orderingof eventsare usuallyevident,asare difficultiesinlearningnew material.Confabulationmaybe

markedbut isnot invariablypresent.Othercognitivefunctionsare usuallyrelativelywell preservedand

amnesicdefects are outof proportiontoother disturbances. Diagnosticguidelines Amnesic

syndrome inducedbyalcohol orotherpsychoactive substancescodedhere shouldmeetthe general

criteriafororganic amnesicsyndrome (seeF04).The primaryrequirementsfor thisdiagnosisare:

(a)memoryimpairmentasshowninimpairmentof recentmemory(learningof new material);

disturbancesof time sense (rearrangementsof chronological sequence,telescopingof repeatedevents

intoone,etc.); (b)absence of defectin immediate recall,of impairmentof consciousness,andof

generalizedcognitive impairment; (c)historyorobjectiveevidence of chronic(andparticularlyhigh-

dose) use of alcohol ordrugs. Personalitychanges,oftenwithapparentapathyandlossof initiative,

and a tendencytowardsself-neglectmayalsobe present,butshouldnotbe regardedasnecessary

conditionsfordiagnosis. Althoughconfabulationmaybe markeditshouldnotbe regardedas a

necessaryprerequisite fordiagnosis.

-75-

Includes:Korsakov'spsychosisorsyndrome,alcohol- or otherpsychoactive substance-induced

Differential diagnosis.Consider:organicamnesicsyndrome (nonalcoholic) (see F04);otherorganic

syndromesinvolvingmarkedimpairmentof memory(e.g.dementiaordelirium) (F00-F03;F05.-);a

depressivedisorder(F31-F33). F1x.7Residual andlate-onsetpsychoticdisorder A disorderinwhich

alcohol- orpsychoactive substance-inducedchangesof cognition,affect,personality,orbehaviour

persistbeyondthe periodduringwhichadirectpsychoactive substance-relatedeffectmightreasonably

be assumedto be operating. Diagnosticguidelines Onsetof the disordershouldbe directlyrelatedto

the use of alcohol ora psychoactive substance.Casesinwhichinitial onsetoccurslaterthanepisode(s)

of substance use shouldbe codedhere onlywhereclearandstrongevidence isavailabletoattribute the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-63-320.jpg)

![64

state to the residual effectof the substance.The disordershouldrepresentachange fromor marked

exaggerationof priorandnormal state of functioning. The disordershouldpersistbeyondanyperiod

of time duringwhichdirecteffectsof the psychoactive substance mightbe assumedtobe operative(see

F1x.0, acute intoxication).Alcohol-orpsychoactive substance-induceddementiaisnotalways

irreversible;afteranextendedperiodof total abstinence,intellectualfunctionsandmemorymay

improve. The disordershouldbe carefullydistinguishedfromwithdrawal-relatedconditions(see F1x.3

and F1x.4).It shouldbe rememberedthat,undercertainconditionsandforcertainsubstances,

withdrawal state phenomenamaybe presentforaperiodof manydays or weeksafterdiscontinuation

of the substance. Conditionsinducedbyapsychoactive substance,persistingafteritsuse,andmeeting

the criteriafor diagnosisof psychoticdisordershouldnotbe diagnosedhere (use F1x.5,psychotic

disorder).Patientswhoshowthe chronicend-stateof Korsakov'ssyndrome shouldbe codedunder

F1x.6.

Differential diagnosis.Consider:pre-existingmental disordermaskedbysubstance use andre-emerging

as psychoactive substance-relatedeffectsfade (forexample,phobicanxiety,adepressivedisorder,

schizophrenia,orschizotypal disorder).Inthe case of flashbacks, consideracute andtransientpsychotic

disorders(F23.-).Consideralsoorganicinjuryandmildormoderate mental retardation(F70-F71),which

may coexistwithpsychoactive substancemisuse. Thisdiagnosticrubricmaybe furthersubdividedby

usingthe followingfive-charactercodes:

-76-

F1x.70 Flashbacks May be distinguishedfrompsychoticdisorderspartlybytheirepisodicnature,

frequentlyof veryshortduration(secondsorminutes) andbytheirduplication(sometimesexact) of

previous drug-relatedexperiences. F1x.71 Personalityorbehaviourdisorder Meetingthe criteriafor

organicpersonalitydisorder(F07.0). F1x.72 Residual affectivedisorder Meetingthe criteriafor

organicmood [affective] disorders(F06.3). F1x.73 Dementia Meetingthe general criteriafor

dementiaasoutlinedinthe introductiontoF00-F09. F1x.74 Otherpersistingcognitive impairment A

residual categoryfordisorderswithpersistingcognitive impairment,whichdonotmeetthe criteriafor

psychoactive substance-inducedamnesicsyndrome(F1x.6) ordementia(F1x.73).

F1x.75 Late-onsetpsychoticdisorder F1x.8Othermental andbehavioural disorders Code here any

otherdisorderinwhichthe use of a substance canbe identifiedascontributingdirectlytothe condition,

but whichdoesnotmeetthe criteriaforinclusioninanyof the above disorders. F1x.9Unspecified

mental andbehavioural disorder F20-F29 Schizophrenia,schizotypalanddelusionaldisorders

Overviewof thisblock F20 Schizophrenia F20.0 Paranoidschizophrenia F20.1 Hebephrenic

schizophrenia F20.2 Catatonicschizophrenia F20.3 Undifferentiatedschizophrenia F20.4 Post-

schizophrenicdepression F20.5 Residual schizophrenia F20.6 Simple schizophrenia F20.8 Other

schizophrenia F20.9 Schizophrenia,unspecified A fifthcharactermay be usedto classifycourse:

F20.x0 Continuous F20.x1 Episodicwithprogressive deficit F20.x2 Episodicwithstable deficit](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-64-320.jpg)

![75

F32.-). Includes:bouffée délirante withoutsymptomsof schizophreniaorunspecified cycloid

psychosiswithoutsymptomsof schizophreniaorunspecified

-88-

F23.1 Acute polymorphicpsychoticdisorderwithsymptomsof schizophrenia Anacute psychotic

disorderwhichmeetsthe descriptivecriteriaforacute polymorphicpsychoticdisorder(F23.0) butin

whichtypicallyschizophrenicsymptomsare alsoconsistentlypresent. Diagnosticguidelines

For a definite diagnosis,criteria(a),(b),and(c) specifiedforacute polymorphicpsychoticdisorder

(F23.0) mustbe fulfilled;inaddition,symptomsthatfulfilthe criteriaforschizophrenia(F20.-) musthave

beenpresentforthe majorityof the time since the establishmentof anobviouslypsychoticclinical

picture. If the schizophrenicsymptomspersistformore than1 month,the diagnosisshouldbe

changedto schizophrenia(F20.-). Includes:bouffée délirante withsymptomsof schizophrenia

cycloidpsychosiswithsymptomsof schizophrenia F23.2 Acute schizophrenia-like psychoticdisorder

An acute psychoticdisorderinwhichthe psychoticsymptomsare comparativelystable andfulfil the

criteriaforschizophrenia(F20.-) buthave lastedforlessthan1 month. Some degree of emotional

variabilityorinstabilitymaybe present,butnotto the extentdescribedinacute polymorphicpsychotic

disorder(F23.0). Diagnosticguidelines

For a definite diagnosis: (a)the onsetof psychoticsymptomsmustbe acute (2 weeksorlessfroma

nonpsychotictoa clearlypsychoticstate); (b)symptomsthatfulfil the criteriaforschizophrenia(F20.-)

musthave beenpresentforthe majorityof the time since the establishmentof anobviouslypsychotic

clinical picture; (c)the criteriaforacute polymorphicpsychoticdisorderare notfulfilled. If the

schizophrenicsymptomslastformore than1 month,the diagnosisshouldbe changedtoschizophrenia

(F20.-). Includes: acute (undifferentiated)schizophrenia brief schizophreniformdisorder brief

schizophreniformpsychosis oneirophrenia schizophrenicreaction Excludes:organicdelusional

[schizophrenia-like] disorder(F06.2) schizophreniformdisorderNOS(F20.8) F23.3 Otheracute

predominantlydelusional psychoticdisorders Acute psychoticdisordersinwhichcomparativelystable

delusionsorhallucinationsare the mainclinical features,butdonotfulfil the criteriaforschizophrenia

(F20.-). Delusionsof persecutionorreference are common,andhallucinationsare usuallyauditory

(voicestalkingdirectlytothe patient). Diagnosticguidelines

For a definite diagnosis:

-89-

(a)the onsetof psychoticsymptomsmustbe acute (2weeksorlessfroma nonpsychotictoa clearly

psychoticstate); (b)delusionsorhallucinationsmusthave beenpresentforthe majorityof the time

since the establishmentof anobviouslypsychoticstate;and (c)the criteriaforneitherschizophrenia

(F20.-) nor acute polymorphicpsychoticdisorder(F23.0) are fulfilled. If delusionspersistformore than](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-75-320.jpg)

![76

3 months,the diagnosisshouldbe changedtopersistentdelusional disorder(F22.-). If only

hallucinationspersistformore than3 months,the diagnosisshouldbe changedtoothernonorganic

psychoticdisorder(F28). Includes:paranoidreaction psychogenicparanoidpsychosis F23.8 Other

acute and transientpsychoticdisorders Anyotheracute psychoticdisordersthatare unclassifiable

underany othercategoryin F23 (suchas acute psychoticstatesinwhichdefinite delusionsor

hallucinationsoccurbutpersistforonlysmall proportionsof the time) shouldbe codedhere. Statesof

undifferentiatedexcitementshouldalsobe codedhere if more detailedinformation aboutthe patient's

mental state isnot available,providedthatthere isnoevidence of anorganiccause. F23.9 Acute and

transientpsychoticdisorder,unspecified

Includes:(brief) reactivepsychosisNOS

F24 Induceddelusionaldisorder

A delusional disordersharedbytwoormore people withclose emotional links. Onlyone of the people

suffersfroma genuine psychoticdisorder;the delusionsare inducedinthe other(s) andusually

disappearwhenthe peopleare separated.

Includes:folie àdeux inducedparanoidorpsychoticdisorder

F25 Schizoaffective disorders

These are episodicdisordersinwhichbothaffectiveandschizophrenicsymptomsare prominentwithin

the same episode of illness,preferablysimultaneously,butatleast withinafew daysof each other.

Theirrelationshiptotypical mood[affective] disorders(F30-F39) andto schizophrenicdisorders(F20-

F24) is uncertain. Theyare givena separate categorybecause theyare toocommonto be ignored.

Otherconditionsin whichaffective symptomsare superimposeduponorformpart of a pre-existing

schizophrenicillness,orinwhichtheycoexistoralternate withothertypesof persistentdelusional

disorders,are classifiedunderthe appropriate categoryinF20-F29. Mood-incongruentdelusionsor

hallucinationsinaffective disorders(F30.2,F31.2, F31.5, F32.3, or F33.3) donot by themselvesjustifya

diagnosisof schizoaffective disorder. Patientswhosufferfromrecurrentschizoaffective episodes,

particularlythose whose symptomsare of the manicrather thanthe depressive type,usuallymake afull

recoveryandonlyrarelydevelopadefectstate. Diagnosticguidelines

-90-

A diagnosisof schizoaffective disordershouldbe made onlywhenbothdefinite schizophrenicand

definiteaffectivesymptomsare prominentsimultaneously,or withinafew daysof each other,within

the same episode of illness,andwhen,asaconsequence of this,the episode of illnessdoesnotmeet

criteriaforeitherschizophreniaor a depressive ormanicepisode. The termshouldnotbe appliedto

patientswhoexhibitschizophrenicsymptomsandaffectivesymptomsonlyindifferentepisodesof

illness. Itiscommon,for example,foraschizophrenicpatienttopresentwithdepressive symptomsin

the aftermathof a psychoticepisode(seepost-schizophrenicdepression(F20.4)). Some patientshave](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-76-320.jpg)

![78

the prognosisislessfavourable. Althoughthe majorityof patientsrecovercompletely,someeventually

developaschizophrenicdefect. Diagnosticguidelines

There mustbe prominentdepression,accompaniedbyatleasttwocharacteristicdepressive symptoms

or associatedbehavioural abnormalitiesaslistedfordepressiveepisode (F32.-);withinthe same

episode,atleastone andpreferablytwotypicallyschizophrenicsymptoms(asspecifiedfor

schizophrenia(F20.-),diagnosticguidelines(a)-(d)) shouldbe clearlypresent. Thiscategory shouldbe

usedbothfor a single schizoaffectiveepisode,depressive type,andfora recurrentdisorderinwhichthe

majorityof episodesare schizoaffective,depressive type. Includes: schizoaffective psychosis,

depressivetype schizophreniformpsychosis,depressivetype F25.2 Schizoaffective disorder,mixed

type Disordersinwhichsymptomsof schizophrenia(F20.-) coexistwiththose of amixedbipolar

affective disorder(F31.6) shouldbe codedhere. Includes: cyclicschizophrenia mixed

schizophrenicandaffective psychosis F25.8 Otherschizoaffectivedisorders F25.9 Schizoaffective

disorder,unspecified

Includes: schizoaffective psychosisNOS

F28 Othernonorganicpsychoticdisorders

Psychoticdisordersthatdonot meetthe criteriaforschizophrenia(F20.-) orforpsychotictypesof mood

[affective] disorders(F30-F39),andpsychoticdisordersthatdonot meetthe symptomaticcriteriafor

persistentdelusionaldisorder(F22.-) shouldbe codedhere. Includes: chronic hallucinatorypsychosis

NOS

F29 Unspecifiednonorganicpsychosis

Thiscategoryshouldalsobe usedfor psychosisof unknownetiology.

Includes: psychosisNOS Excludes: mental disorderNOS (F99) organicor symptomaticpsychosis

NOS(F09) F30-F39 Mood [affective]disorders

Overviewof thisblock

F30 Manic Episode F30.0 Hypomania

-92-

F30.1 Mania withoutpsychoticsymptomsF30.2Mania withpsychoticsymptomsF30.8 Othermanic

episodesF30.9Manic episode,unspecified F31Bipolaraffective disorderF31.0Bipolaraffective

disorder,currentepisodehypomanicF31.1Bipolaraffective disorder,currentepisodemanicwithout

psychoticsymptomsF31.2Bipolaraffectivedisorder,currentepisode manicwithpsychoticsymptoms

F31.3Bipolaraffctive disorder,currentepisodemildormoderate depression .30Withoutsomatic

syndrome .31 Withsomaticsyndrome F31.4Bipolaraffective disorder,currentepisode severe

depressionwithoutpsychoticsymptomsF31.5Bipolaraffective disorder,currentepisodesevere](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-78-320.jpg)

![79

depressionwithpsychoticsymptomsF31.6Bipolaraffective disorder,currentepisode mixed

F31.7Bipolaraffective disorder,currentlyinremissionF31.8Otherbipolaraffectivedisorders

F31.9Bipolaraffective disorder,unspecified F32Depressive episode F32.0Milddepressiveepisode .00

Withoutsomaticsyndrome .01 With somaticsyndrome F32.1 Moderate depressiveepisode .10

Withoutsomaticsyndrome .11 With somaticsyndrome F32.2 Severe depressive episodewithout

psychoticsymptomsF32.3 Severe depressive episode withpsychoticsymptomsF32.8Otherdepressive

episodesF32.9Depressive episode,unspecified

-93-

F33 Recurrentdepressive disorderF33.0Recurrentdepressive disorder,currentepisodemild .00

Withoutsomaticsyndrome .01 With somaticsyndrome F33.1 Recurrentdepressive disorder,current

episode moderate .10 Withoutsomaticsyndrome .11 Withsomaticsyndrome F33.2Recurrent

depressivedisorder,currentepisode severewithoutpsychoticsymptomsF33.3Recurrentdepressive

disorder,currentepisodesevere withpsychoticsymptomsF33.4Recurrentdepressivedisorder,

currentlyinremissionF33.8Otherrecurrentdepressive disordersF33.9Recurrentdepressivedisorder,

unspecified F34Persistentmood[affective]disordersF34.0CyclothymiaF34.1 DysthymiaF34.8 Other

persistentmood[affective]disordersF34.9Persistentmood[affective] disorder,unspecified F38Other

mood[affective] disordersF38.0Othersingle mood[affective] disorders .00Mixedaffective episode

F38.1 Otherrecurrentmood[affective] disorders .10Recurrentbrief depressivedisorderF38.8 Other

specifiedmood[affective] disorders F39 Unspecifiedmood[affective] disorder

-94-

Introduction

The relationshipbetweenetiology,symptoms,underlyingbiochemical processes,response to

treatment,andoutcome of mood[affective] disordersisnotyetsufficientlywell understoodtoallow

theirclassificationinaway thatis likelytomeetwithuniversalapproval. Nevertheless,aclassification

mustbe attempted,andthatpresentedhere isputforwardinthe hope thatit will atleastbe

acceptable,since itisthe resultof widespreadconsultation.

In these disorders,the fundamental disturbance isachange inmoodor affect,usuallytodepression

(withorwithoutassociatedanxiety) ortoelation. Thismoodchange isnormallyaccompaniedbya

change in the overall level of activity,andmostothersymptomsare eithersecondaryto,oreasily

understoodinthe contextof,suchchanges. Most of these disorderstendtobe recurrent,andthe onset

of individual episodesisoftenrelatedtostressful eventsorsituations. Thisblockdealswithmood

disordersinall age groups;those arisinginchildhoodandadolescence shouldtherefore be codedhere.

The main criteriabywhichthe affective disordershave beenclassifiedhave beenchosenforpractical

reasons,inthat theyallowcommonclinical disorderstobe easilyidentified. Single episodeshave been](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/icd-161127112927/85/Icd-79-320.jpg)

![86

gradesof severity,adurationof atleast2 weeksisusuallyrequiredfordiagnosis,butshorterperiods

may be reasonable if symptomsare unusuallysevere andof rapidonset.

Some of the above symptomsmaybe markedanddevelopcharacteristicfeaturesthatare widely

regardedas havingspecial clinical significance. The mosttypical examplesof these "somatic"symptoms

(see introductiontothisblock,page 112 [of Blue Book]) are:lossof interestorpleasure inactivitiesthat

are normallyenjoyable;lackof emotional reactivitytonormallypleasurablesurroundingsandevents;

wakinginthe morning2 hours or more before the usual time;depressionworseinthe morning;

objective evidence of definite psychomotorretardationoragitation(remarkedonorreportedbyother

people);markedlossof appetite;weightloss(oftendefinedas5% or more of bodyweightinthe past

month);markedlossof libido. Usually,thissomaticsyndrome isnotregardedaspresentunlessabout

fourof these symptomsare definitelypresent.

The categoriesof mild(F32.0),moderate (F32.1) and severe (F32.2and F32.3) depressive episodes

describedinmore detail belowshouldbe usedonlyforasingle (first) depressive episode. Further

depressiveepisodesshouldbe classifiedunder one of the subdivisionsof recurrentdepressive disorder

(F33.-).

These gradesof severityare specifiedtocoverawide range of clinical statesthatare encounteredin

differenttypesof psychiatricpractice. Individualswithmilddepressiveepisodesare commoninprimary

care and general medical settings,whereaspsychiatricinpatientunitsdeal largelywithpatientssuffering

fromthe severe grades.

-101-

Acts of self-harmassociatedwithmood[affective] disorders,mostcommonlyself-poisoningby

prescribedmedication,shouldbe recordedbymeansof anadditional code fromChapterXXof ICD-10