The Infrastructure Blue Ribbon Commission was appointed by the Palo Alto City Council to assess the state of the city's infrastructure and make recommendations. The Commission found that Palo Alto has underfunded infrastructure maintenance by over $2 million per year, resulting in over $40 million in backlogged needs. It recommends increasing annual infrastructure spending by $6 million and replacing five major facilities including the police headquarters and two fire stations for $79 million. It also recommends funding a $100 million study and redevelopment of the Municipal Services Center area. To prevent future issues, the Commission recommends creating an infrastructure management system and single point of responsibility. It presents four alternatives to fund the recommendations that include tax increases or utilizing potential savings from ending contracts with the

![PUBLIC

SAFETY

FACILITIES

IBRC

FINAL

REPORT

45

Figure

3-‐2.

Evidence

storage

for

the

Palo

Alto

Police

Department

(left)

is

well

below

current

law

enforcement

standards

and

is

cramped

for

space.

Current

standards

call

for

updating

Palo

Alto

to

a

system

like

the

evidence

storage

lockers

used

by

San

Mateo

(right).

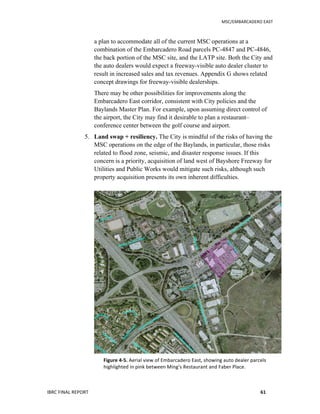

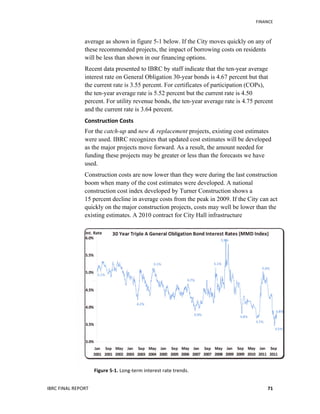

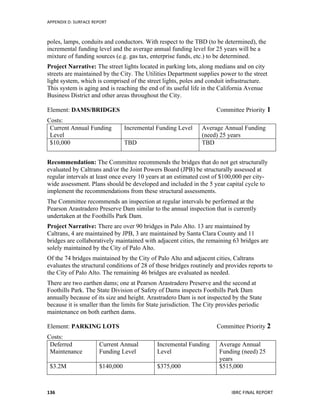

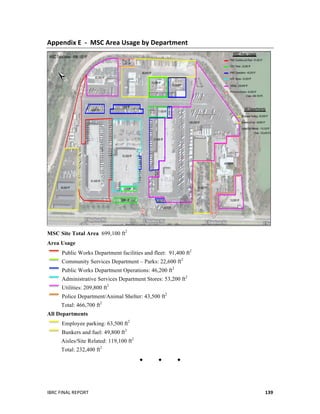

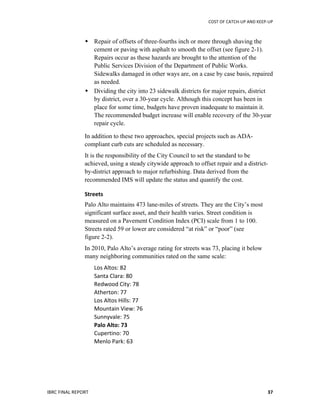

4. The current PSB lacks blast protection from outside and below (see

figure 3-3). The PSB and fire stations were built for the last century’s

public safety and community service needs, not for current and

projected emergency response services.

5. Estimated replacement costs are Public Safety Building – $65 million;

Fire Station 3 – $6.7 million; Fire Station 4 – $7.5 million. [Note:

These estimates are several years old and would need to be redone with

specific designs in mind. In the case of the contemplated Public Safety

Building, its contents would include elements not included in the

previously estimated structure, namely, an Office of Emergency

Services and the administrative component of the Fire Department.

These are together estimated to add another 7,500 square feet plus

allowances for circulation and shared spaces, additions which have

been included in the $65 million estimate. In the case of Fire Station 4,

the 2005 cost estimate includes a meeting room no longer needed since

the construction of the Mitchell Park Community Center; this removes

approximately 1,000 square feet from the conceptual design.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dc00a1f9-2b14-443b-9811-d4b7c2ff2c65-150804215126-lva1-app6891/85/IBRC-Final-Report_12-22-2011-51-320.jpg)