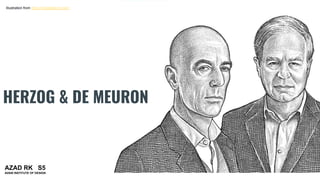

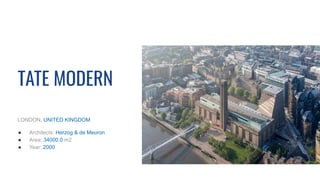

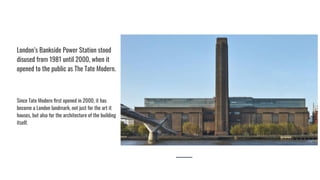

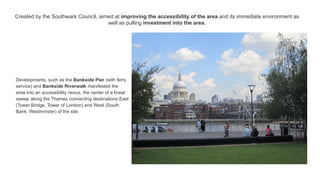

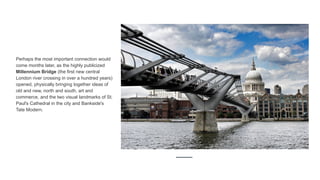

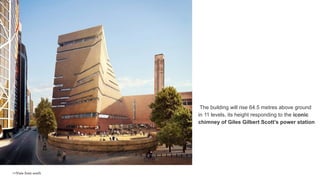

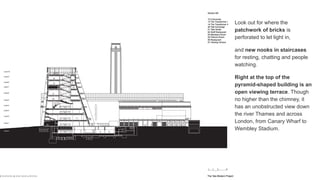

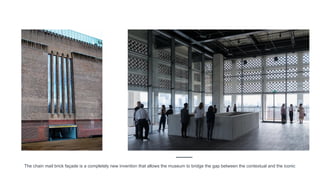

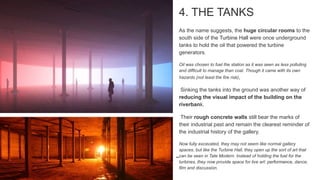

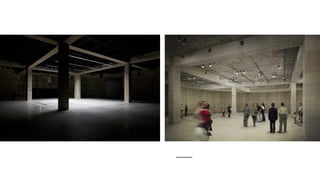

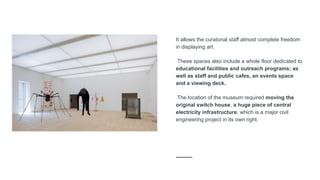

Herzog & de Meuron are Swiss architects known for their minimalist yet organically integrated designs, with a notable emphasis on materiality and dynamic geometries. Their most famous project, the Tate Modern in London, transformed a disused power station into a major cultural landmark, emphasizing sustainability and community engagement through innovative new spaces. The recent addition to the Tate enhances its capacity and maintains a connection to its industrial roots while promoting environmental efficiency and artistic diversity.