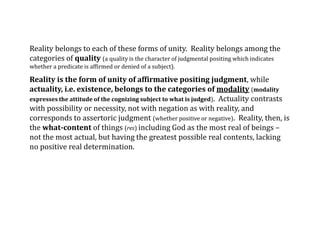

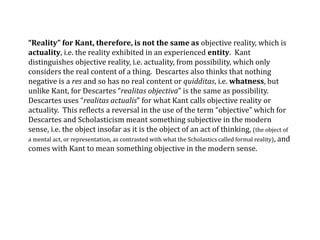

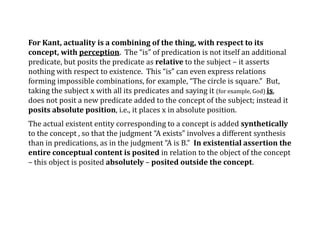

This document outlines Kant's thesis that being is not a real predicate. It discusses Kant's rejection of the ontological proof for God's existence, which tries to prove God exists from the concept of God alone. For Kant, existence does not belong to the determinateness of any concept. The document then explains some of Kant's key terminology, such as how he distinguishes between being, existence, reality, and actuality. It analyzes Kant's view that existence involves absolutely positioning a thing, rather than relating it to other things through predication. In existential assertions, the entire conceptual content is posited in relation to the object itself.

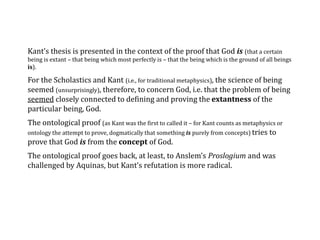

![Kant, instead, accepts the major premise [which Aquinas rejected] and [in a way

accepts] the conclusion, but denies the minor premise.

Kant claims that existence does not belong to the determinateness of

any concept at all. This claim is the thesis that existence is not a real

predicate.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-10-320.jpg)

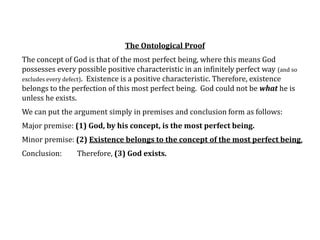

![In the essay “The Sole Possible Argument for a Demonstration of God's

Existence,” Kant explicates the notion of existence in three theses:

1st thesis: “Existence is not a [real] predicate or determination of any

thing at all.” (or “Being is manifestly not a real predicate, that is, a concept of something

that could be added to the concept of a thing.”).

This gives a negative characterization of existence.

2nd thesis: “Existence is the absolute position of a thing and thereby

differs from any sort of predicate, which as such, is posited at each

time merely relative to another thing.” (or Being “is merely the position of a

thing or of certain determinations in themselves.”)

This gives a positive definition of existence.

3rd thesis is presented in the form of a question: “Can I really say that

there is more in existence than in mere possibility?” This question

asks about Christian Wolff’s claim that the existence of a thing

accompanies its possibility.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-11-320.jpg)

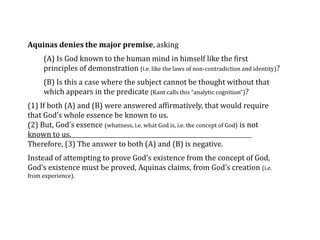

![Note that Kant does not differentiate being in general from existence

[extantness], while Kant does distinguish between something existing and

something being real.

Insofar as a predicate is what is asserted in a judgment it seems as though we

do assert extantness of things (res), we say “God exists.” “This table exists.” etc.

For Kant, the understanding acts by combining [synthesizing] something with

something – this amounts to a formal definition of assertion abstracted from

what (materially) is combined with something else – the “I combine,” i.e.

synthesis, in judgment.

This formal characterization is insufficient to resolve whether existence is a

real predicate, since existence has a specific content. A real predicate is a

determination, i.e., a predicate which, when added, enlarges the subject

from beyond what is already contained in the subject (a determination that is not

already contained in the concept of the subject), and so requires a synthetic judgment.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-12-320.jpg)

![Kant uses the term “reality” [Realität] to mean the determination of a thing (res)

in terms of its possibilities. Realities are the what-contents of possible

things in general regardless of their actuality. Kant uses the term

“objective reality” to mean existence. This terminology is precise, although we

have yet to find out whether it is adequate.

Kant derives this terminology from Baumgarten: “that which is posited as

being A or posited as being not-A is determined.” Determination is the

determination of a res. Determinations may be affirmative or negative. So,

reality means the real determination of a thing (res), i.e., affirmatively posited

predicates, and their opposites which are their negations, for example, a table

may have the determination green and so fall under the predicate “green” or

not have the determination green and so fall under the predicate “not-green”.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-13-320.jpg)

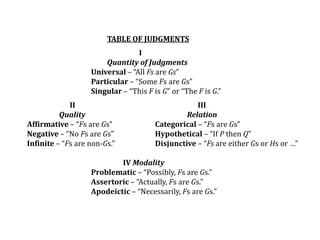

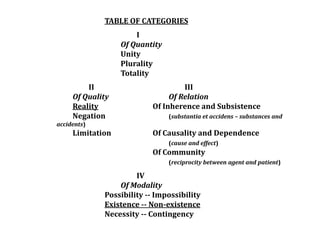

![Formally, judgments combine subject and predicate with respect to a

possible unity. The categories are the different possible forms of unity of

combination in judgments (categories are not forms molding pre-given material). The

table of judgments gives all possible form of union from which the

categories, the ideas of unity, can be read off.

[Note: infinite judgments only differ from affirmative judgments with respect to transcendental

logic. See below!]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-14-320.jpg)

![“Existence is not a reality” means existence is not a determination of

the concept of a thing with respect to its real content. An actual x does

not differ in its real content [its what-content, i.e. what it is] from a possible x. The

what-content of a possible x coincides with the what-content of the actual

x. Thinking “that x exists” adds nothing to the thing (res). Otherwise the

actual x would include more than in its concept and we could not ever say

that exactly the same object of my concept exists.

“Thus when I think a thing, through whichever and however many predicates I like (even in its

thoroughgoing determination), not the least bit gets added to the thing when I posit in addition that

this thing is. For otherwise what would exist would not be the same as what I had thought in my

concept, but more than that, and I could not say that the very object of my concept exists.”

Critique of Pure Reason A6oo/B628](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-19-320.jpg)

![In common linguistic usage, however, the word “exists” does occur as a

grammatical predicate, and in the broadest sense the word “is” is involved

in every predication as the copula, for example “Body is extended.” The

copulative sense of “is” links a subject concept to a predicate, and is

distinct from the existential sense of ‘is,” as in, for example “God is.”

[As Bertrand Russell pointed out we must distinguish the “is” of predication from the “is” of

existence. Russell said that is was a crime that the English language used the same word to

express these two very differtent concepts.]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-20-320.jpg)

![How can being be determined positively, if being is not a real predicate?

How does existence differ from being in general?

Being in general is position in general, according to Kant. Position is

inherently simple [position, to posit – to place]. The mere position or realities of a

thing constitute the thing’s concept as its possibility in accord with the law of

non-contradiction, but this positing is only relative, i.e., predication is always

relative to another thing [mere position as in ‘A is B’ is combining B with A in a judgment

that obeys the law of non-contradiction].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-21-320.jpg)

![In attributing existence, we do not refer (merely relatively) to another thing or to

some other feature of a thing, but we posit (position, i.e. to take a position –

affirmative, negative, or neutral – with respect to some object) the thing in and for

itself without relation, i.e. we posit the thing’s position absolutely [The whole

of ‘A is B’ is posited in itself]. So, existence is absolute position and differs from mere

[or relative] position (being something). Neither absolute nor mere (relative) position

is a real predicate.

[So, for example the term ‘brown’ expresses a reality, i.e. mere position, and combining the concept

‘table’ with ‘brown,’ using the ‘is’ of predication, constructs a judgment ‘The table is brown.’ This

posits ‘brown’ relative to ‘table’ within the judgment. Absolute position, instead posits the whole of

the judgment ‘The table is brown.’

“When, on the other hand, I say “Something exists,” in this positing I am not making a relational

reference to any other thing or to some other characteristic of a thing, to some other real being;

instead, I am here positing the thing in and for itself, free of relation; I am positing here without

relation, non-relatively, i.e. absolutely. In the proposition “A exists,” “A is extant,” an absolute positing

is involved.” pp. 39-40]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-22-320.jpg)

![What is posited?

A possible thing (the possible thing’s what-content).

How is it posited?

The absolute position of the thing is posited over and above its mere

possibility.

In absolute position, a relation is posited between the object itself and

its concept.

Existence is thought, for Kant, in the [grammatical] subject, and not in the

predicate, saying “Existence belongs to x.” Existence is thought of the thing,

rather than as predicate of the thing, despite common usage. The concept of

a thing contrast sharply with the object (Gegenstand), the thing itself. “God

exists,” then, means “Something existing is God.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-24-320.jpg)

![Hence, the ontological proof of God’s existence fails, since existence

cannot belong to the concept of a thing; hence, the pure conceptual content

of a thing can never assure its existence, unless one presup-poses [vor-

aussetzen – set out before one – to take a postion with respect to] the thing’s actuality,

which would be tautologous.

Thus, Kant refutes the minor premise. This is far more devistating than

Aquinas’s refutation which only appeals to the limits of our understanding.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-25-320.jpg)

![Our interest is in Kant’s conceptions of being, that being is position, and that

existence is absolute position [we are not interested in God as a being]. But, we must

ask whether this is adequate, by pushing the Kantian account to its limits to

test its clarity.

“Can we reach a greater degree of clarity within the Kantian

approach itself?

Can it be shown that the Kantian explanation does not really have

the clarity it claims?

Does the thesis that being equals position, i.e. existence equals

absolute position, perhaps lead us into the dark?” pp. 42-43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-26-320.jpg)

![§ 8. Phenomenological analysis of the explanation of the concept of being

or of existence given by Kant

a) Being (existence [Dasein, Existenz, Vorhandensein]), absolute position, and

perception

For Kant (and the tradition), reality is what belongs to a thing, for example, walls

and color belong to a house. Actuality, on the other hand, does not determine

the what, but rather the how of a being. Negatively, actuality is not a real

determination, is not itself anything actual. As Heidegger repeatedly says:

being [to be] is not a being.

Positively, Kant identifies being with position and existence with absolute

position.

Can we understand this more clearly?

Is this account justifiable?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-27-320.jpg)

![In the table of categories with respect to modality:

Existence, then (for Kant), expresses a relation between the object and

the faculty of cognition [knowing].

Possibility (for Kant) expresses the relation of the object, with all its

determinations, with respect to mere thinking.

Actuality (for Kant) correlates with the empirical use of the faculty of the

understanding.

Necessity (for Kant) correlates the object with reason, insofar as reason

is applied to experience.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-30-320.jpg)

![The inaccessibility of the constitution of the being of their domains applies

even more to the factual sciences, for example, psychology inevitably makes

presuppositions about the constitution of Dasein and her way of being. So, as

Plato says [Republic VII, 533b6ff], positive sciences only dream about the

existence of their objects, because of their inevitable presuppositions.

Yet while dreaming in this way, the positive sciences arrive at their results,

only momentarily waking now and then to the need to examine the being of

their domains, when their basic concepts are in question.

In contrast, philosophy takes the a priori as such as its theme.

Philosophy, then, is uncomfortable for common understanding, and the

positive science’s (in particular psychology’s) conception of philosophy is displaced

to make it accessible to common understanding, since the common

understanding is impressed by facts.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-39-320.jpg)

![The task, then, becomes the elucidation of the structure of intentionality.

Intentionality is a structure of Dasein’s comportments.

How is intentionality grounded ontological in the constitution of Dasein?

We must avoid misinterpretation due either to philosophical theories or,

especially, to a naive naturalistic approach (including everyday “good sense”).

Firstly, it is, mistakenly, supposed that intentionality in perception, for

example, is a relation between two beings: an extant subject and an extant

object.

Given this naturalistic conception, we see what happens if we vary these, and

we find that if either subject or object vanishes so does the relation. So,

intentionality, as understood within the natural attitude, requires the

extantness of both object and subject, where each would remain were the

other removed [for example as in Descartes’ doubting the existence of the causes of his ideas].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-45-320.jpg)

![This (theoretical approach) seems to raise several questions:

How do these subjectivities relate to objectivities?

What can this immanent relation contribute to the philosophical

elucidation of transcendence [that which is outside the subject]?

“How do we proceed from inside the intentional experiences in the subject outward to things as

objects?” p. 62

How can experiences transcend [get outside] the subjective sphere?

“How do experiences and that to which they direct themselves as intentional, the subjective in

sensations, representations, relate to the objective?” p. 62](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-49-320.jpg)

![“Time and again it becomes necessary to impress on ourselves the methodological maxims of

phenomenology not to flee prematurely from the enigmatic character of phenomena nor to explain

it away by the violent coup de main of a wild theory but rather to accentuate the puzzlement.

Only in this way does it become palpable and conceptually comprehensible, that is, intelligible and

so concrete that the indications for resolving the phenomenon leap out toward us from the

enigmatic matter itself.” p. 69 [emphasis PT]

This applies to the problem of perceiving, namely, that perceiving belongs

somehow to the object without being objective and belongs somehow to

Dasein without being subjective.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-59-320.jpg)

![Perception, in the sense of the perceivedness of the extant is not itself

extant, but belongs to Dasein without being subjective.

• Perception uncovers the extant so that the extant thing can show

itself, and the uncoveredness of the extant is already implicit in

perception.

• In perception the extant shows itself in its own self (is itself presented).

• Perception is not equivalent to representation (representation also intends

the object, but in representation the extant is not itself presented, in its own self).

• Perception is a mode of intentionality in which the extant is released

and lets itself be encountered. Therefore, perception is a mode of

uncoveredness.

• Dasein exists as uncovering [i.e. Dasein exists as the act of uncovering of that which

is extant].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-60-320.jpg)

![We must now manage to exhibit more precisely the interconnection between the uncoveredness of a

being and the disclosedness of its being and to show how the disclosedness (unveiledness) of being

founds, that is to say, gives the ground, the foundation, for the possibility of the uncoveredness of the

being. In other words, we must manage to conceptualize the distinction between uncoveredness and

disclosedness, its possibility and necessity, but likewise also to comprehend the possible unity of the

two. This involves at the same time the possibility of formulating the distinction between the being

[Seienden] that is uncovered in the uncoveredness and the being [Sein] which is disclosed in the

disclosedness, thus fixing the differentiation between being and beings, the ontological difference. In

pursuing the Kantian problem we arrive at the question of the ontological difference. Only on the path

of the solution of this basic ontological question can we succeed in not only positively corroborating

the Kantian thesis that being is not a real predicate but at the same time positively supplementing it by

a radical interpretation of being in general as extantness (actuality , existence). p. 72

Hence we have arrived at the question of the ontological difference which we

aimed at in following the Kantian problematic. We can conclude that the

question of the ontological difference can not be extricated from the

investigation of intentionality (i.e. of all intentionalities, not just that of perception).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/heideggerbasicproblemsch1ppt-221105043740-054005c5/85/Heidegger_Basic_Problems_ch_1_ppt-pptx-63-320.jpg)