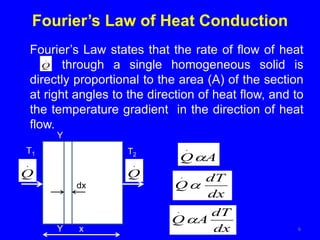

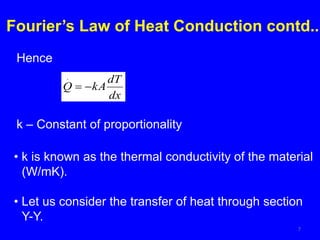

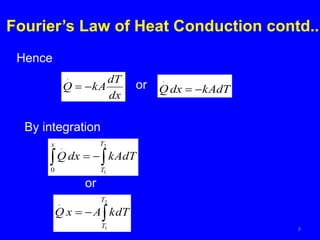

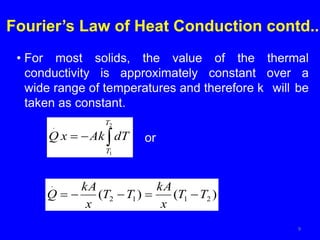

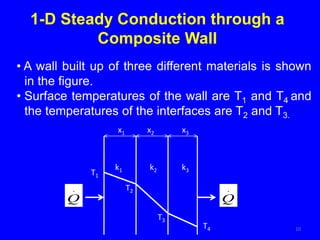

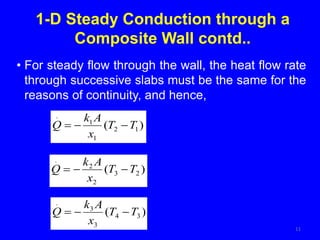

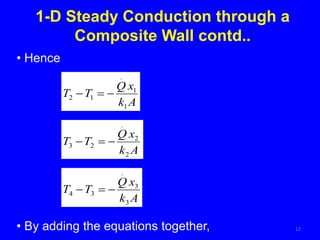

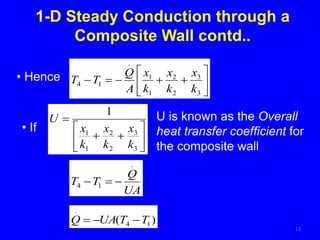

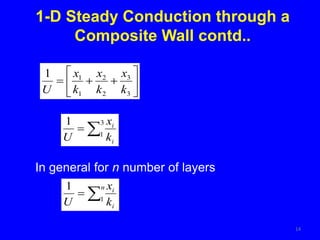

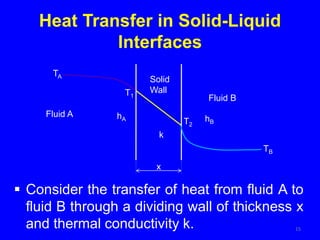

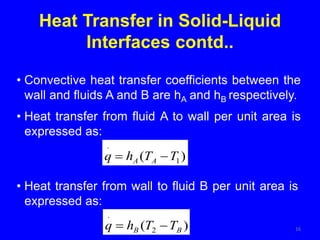

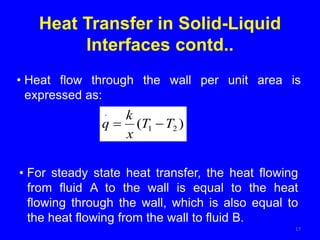

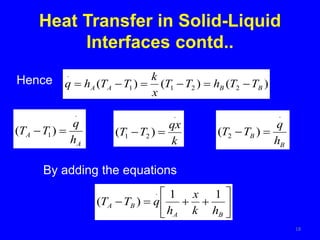

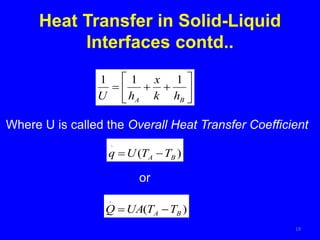

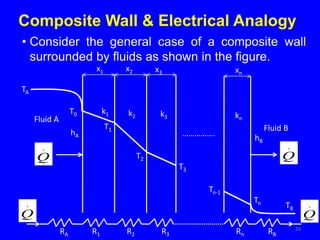

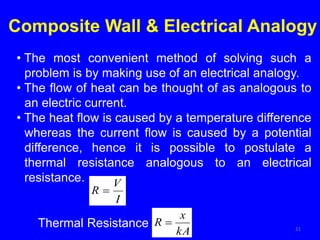

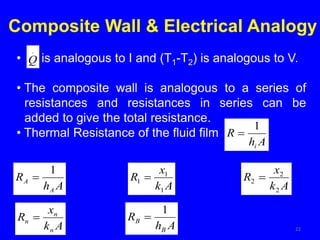

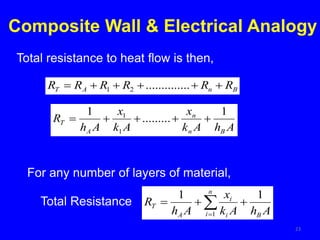

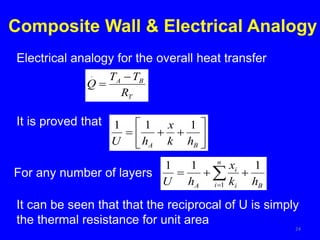

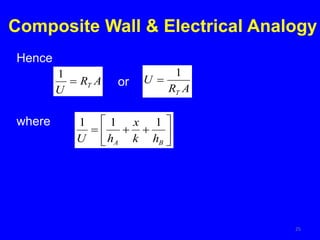

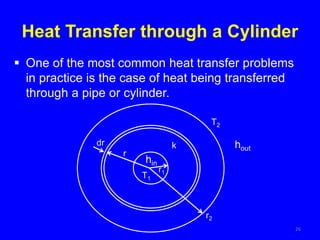

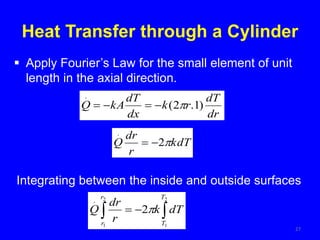

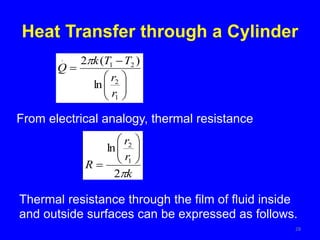

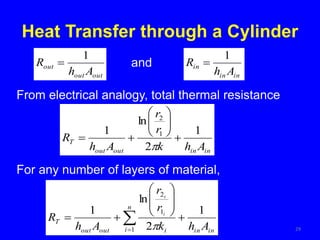

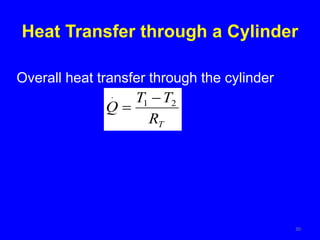

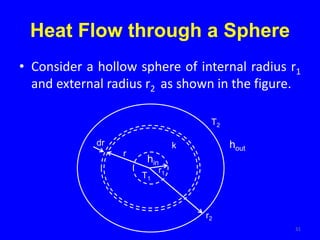

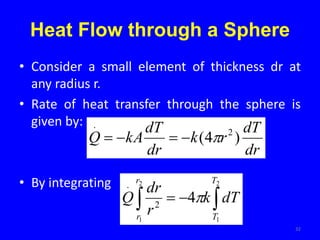

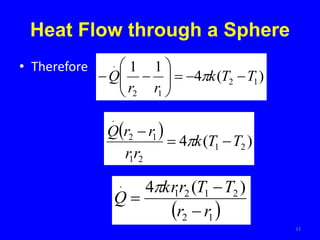

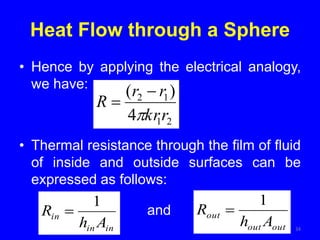

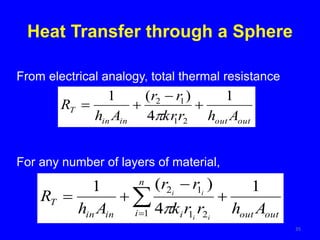

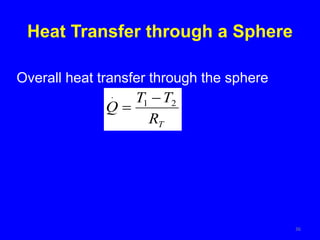

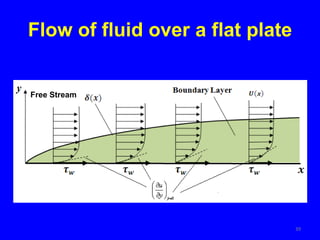

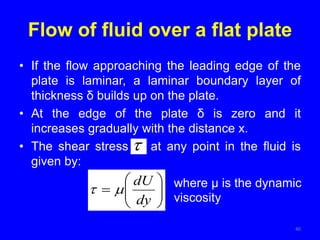

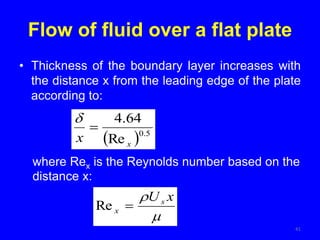

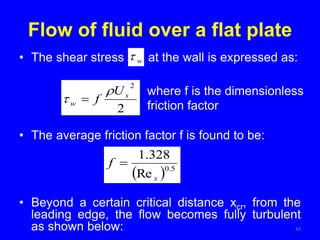

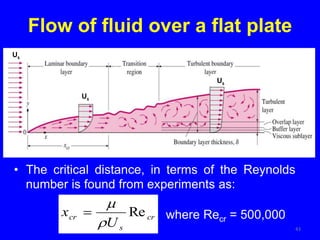

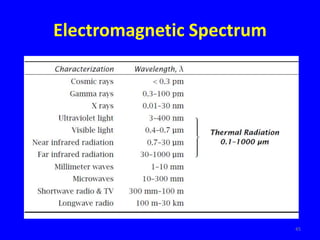

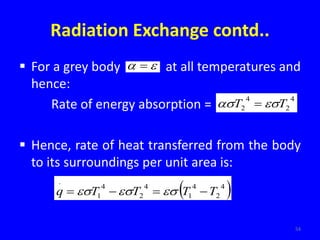

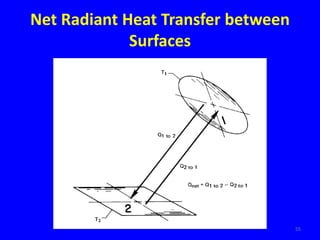

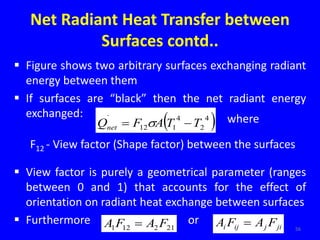

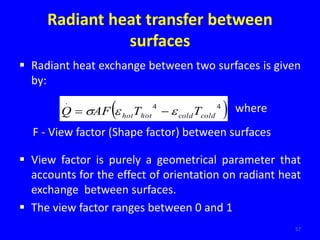

The document provides an overview of heat transfer, which encompasses conduction, convection, and radiation. It explains mechanisms of heat transfer in solids, fluids, and composite walls, detailing Fourier's law and principles of thermal resistance using electrical analogies. Additionally, it discusses specific heat transfer scenarios involving cylinders, spheres, and fluid flow over surfaces, emphasizing the significance of boundary layers and other related phenomena.