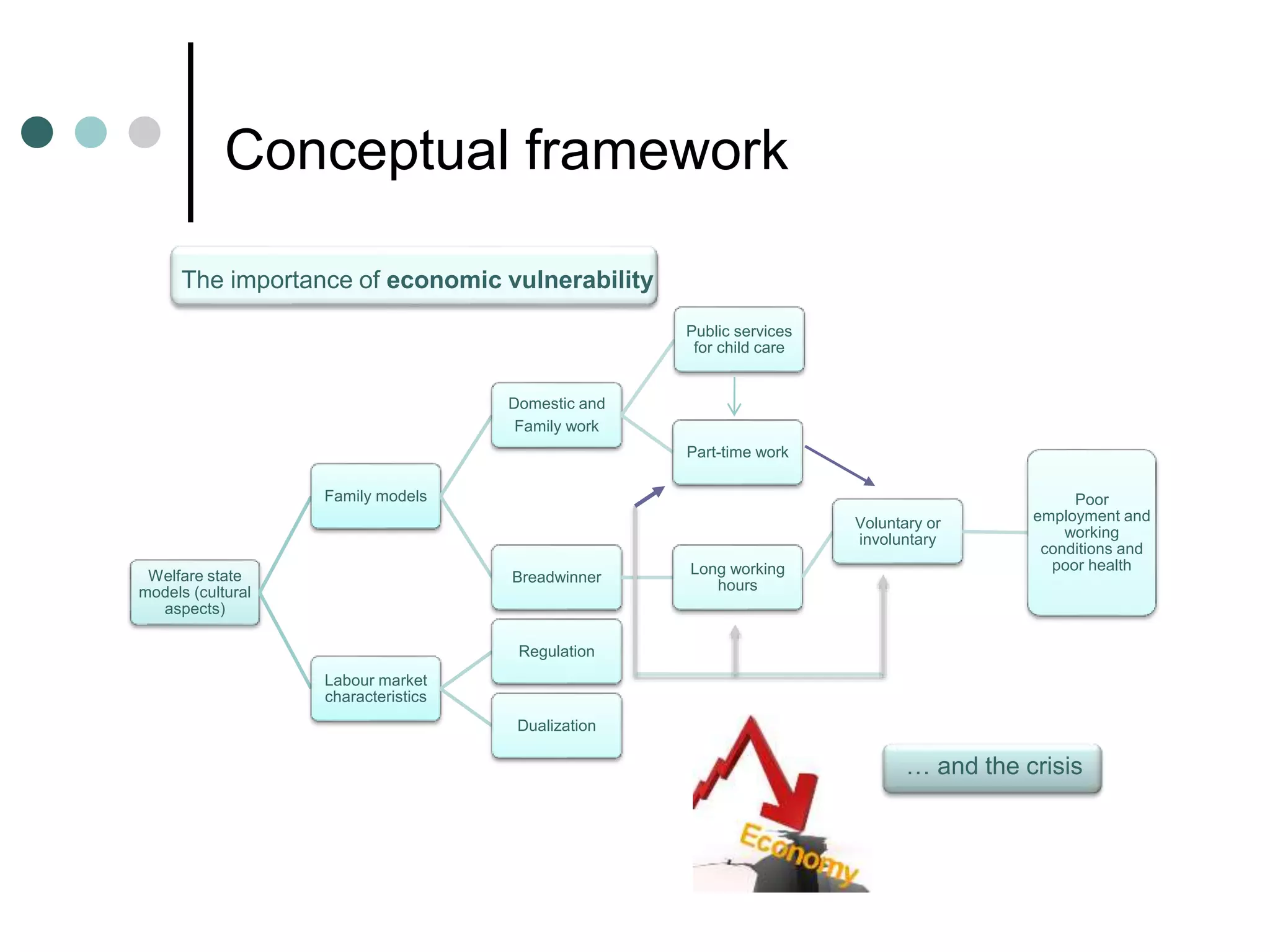

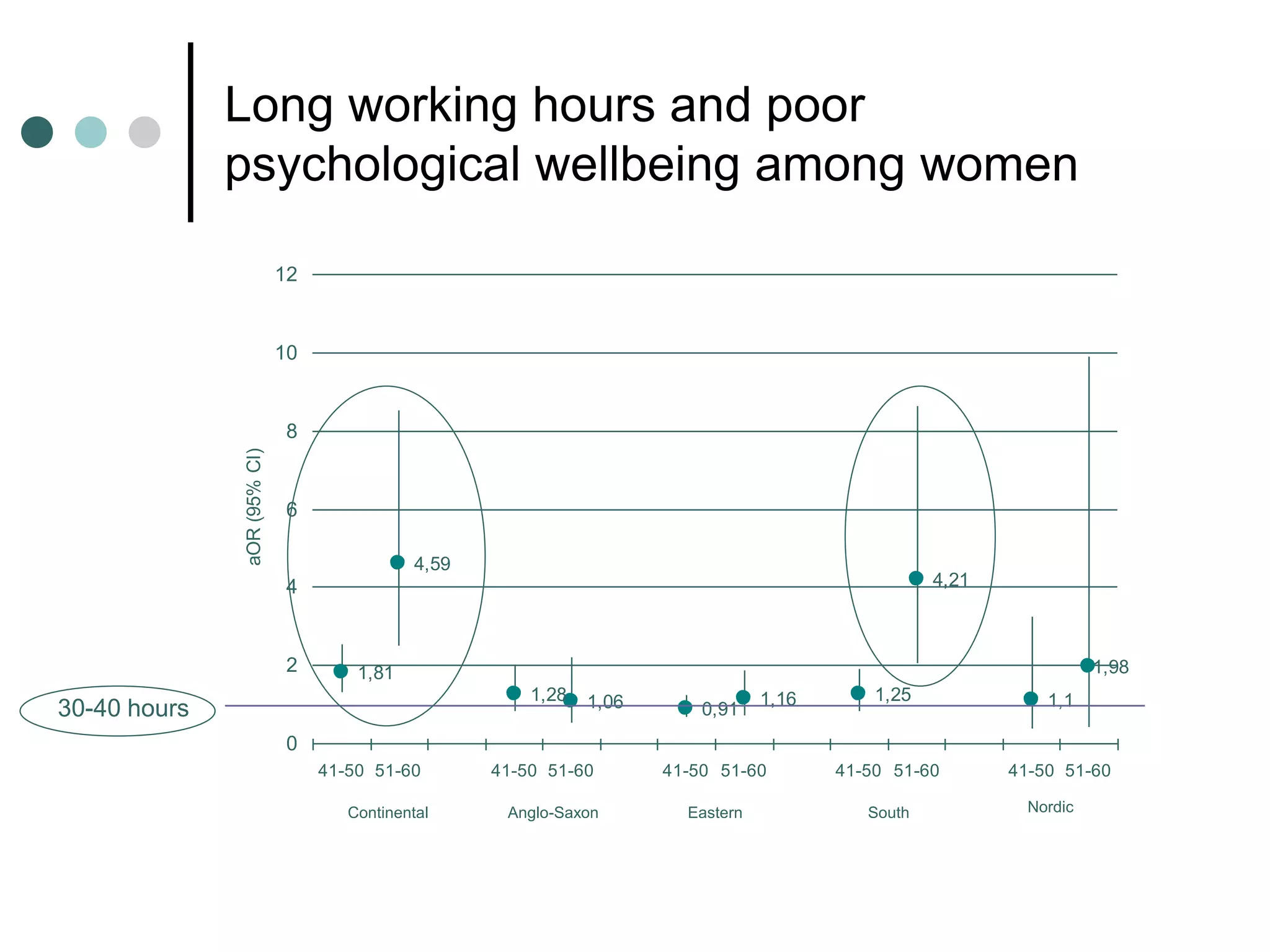

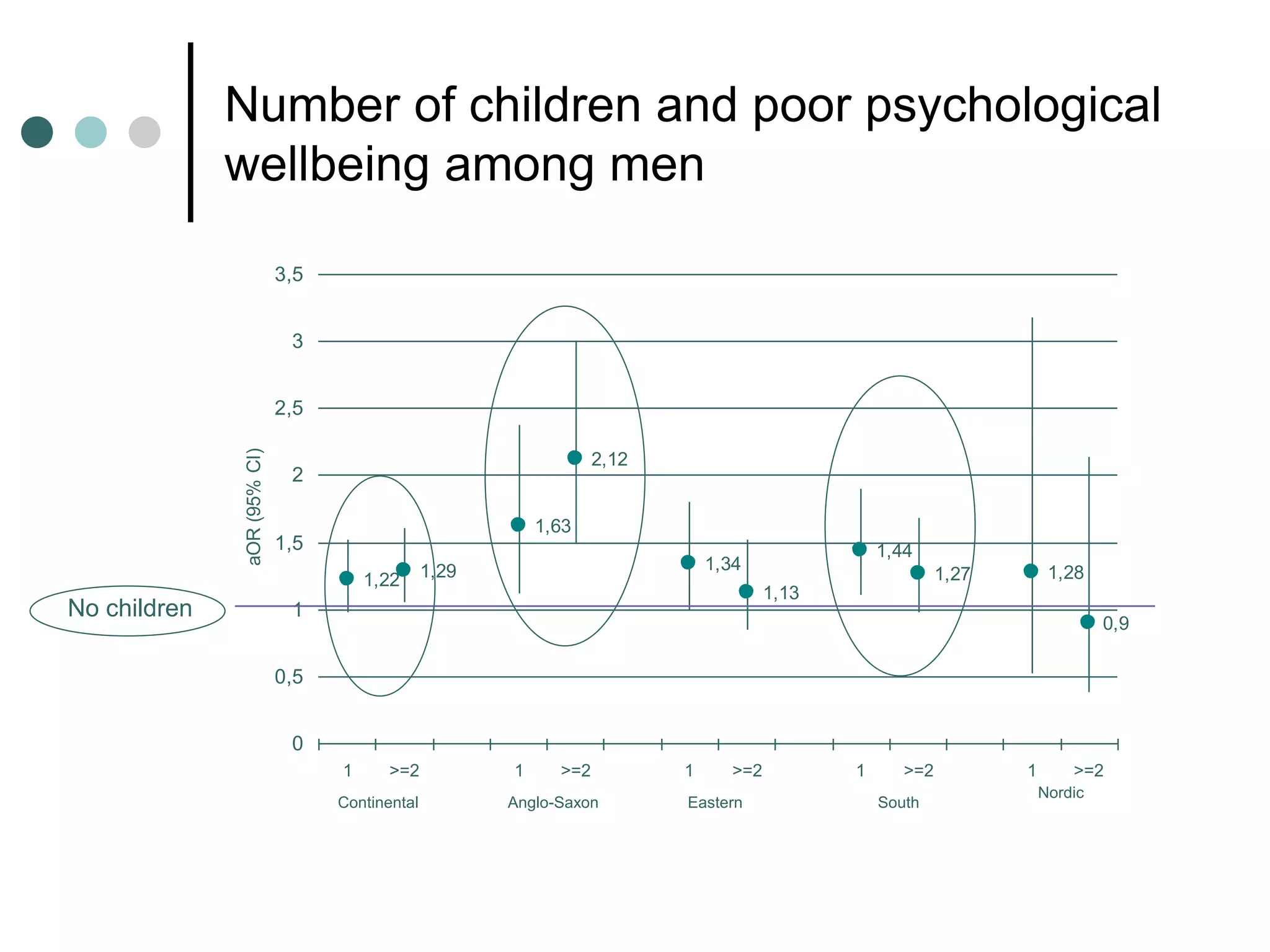

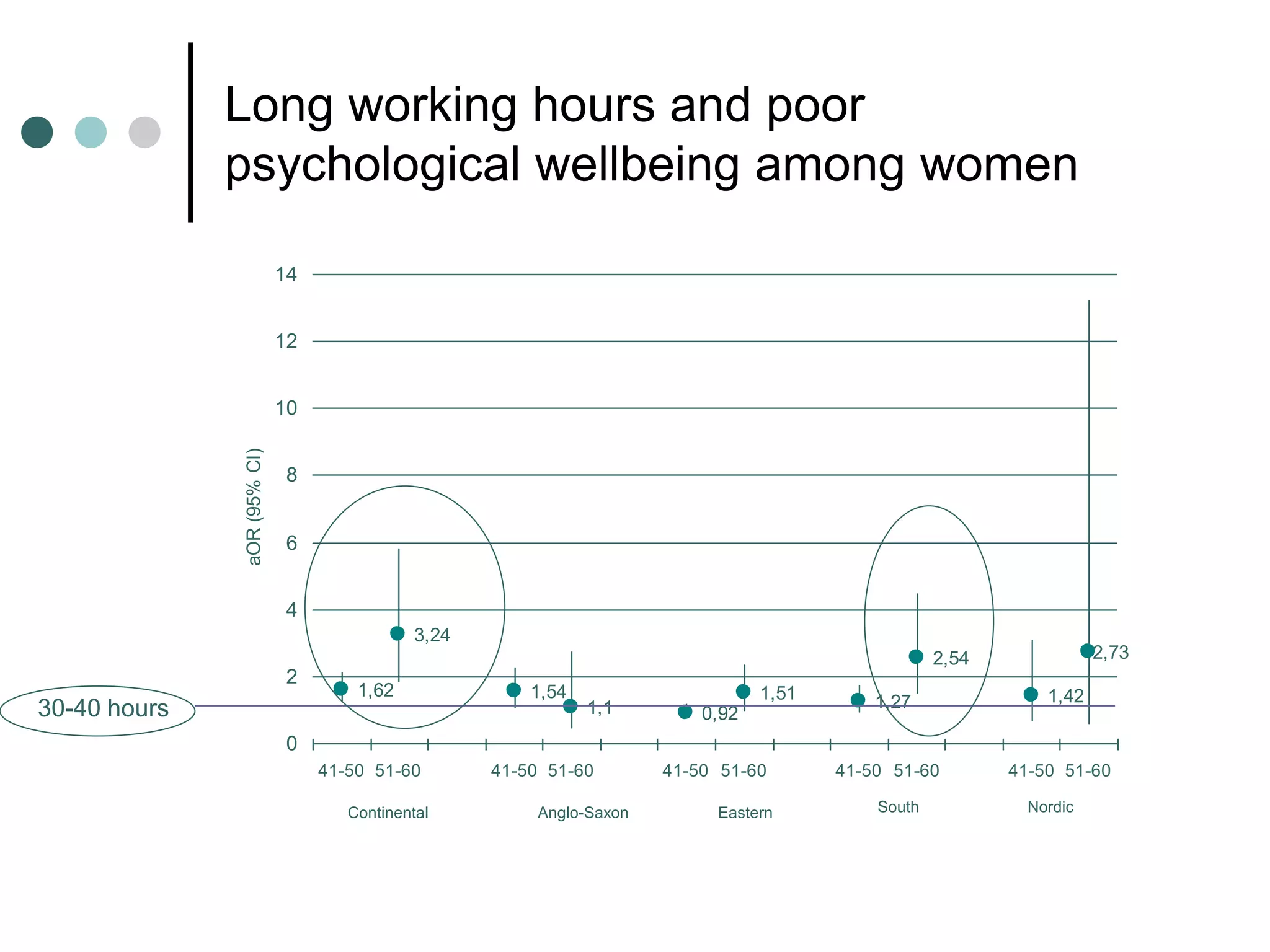

This document outlines a presentation on health inequalities related to gender differences in working time in Europe. It discusses how welfare state regimes influence the gender division of labor, family roles, and working hours. Research presented found that long working hours and family demands were associated with poorer health, especially for women in Continental and Southern European countries. Nordic and Eastern European countries saw fewer associations between working hours/family demands and health outcomes for both men and women. The conceptual framework examines how welfare states, labor markets, family models, and public services influence the gender division of work and health.