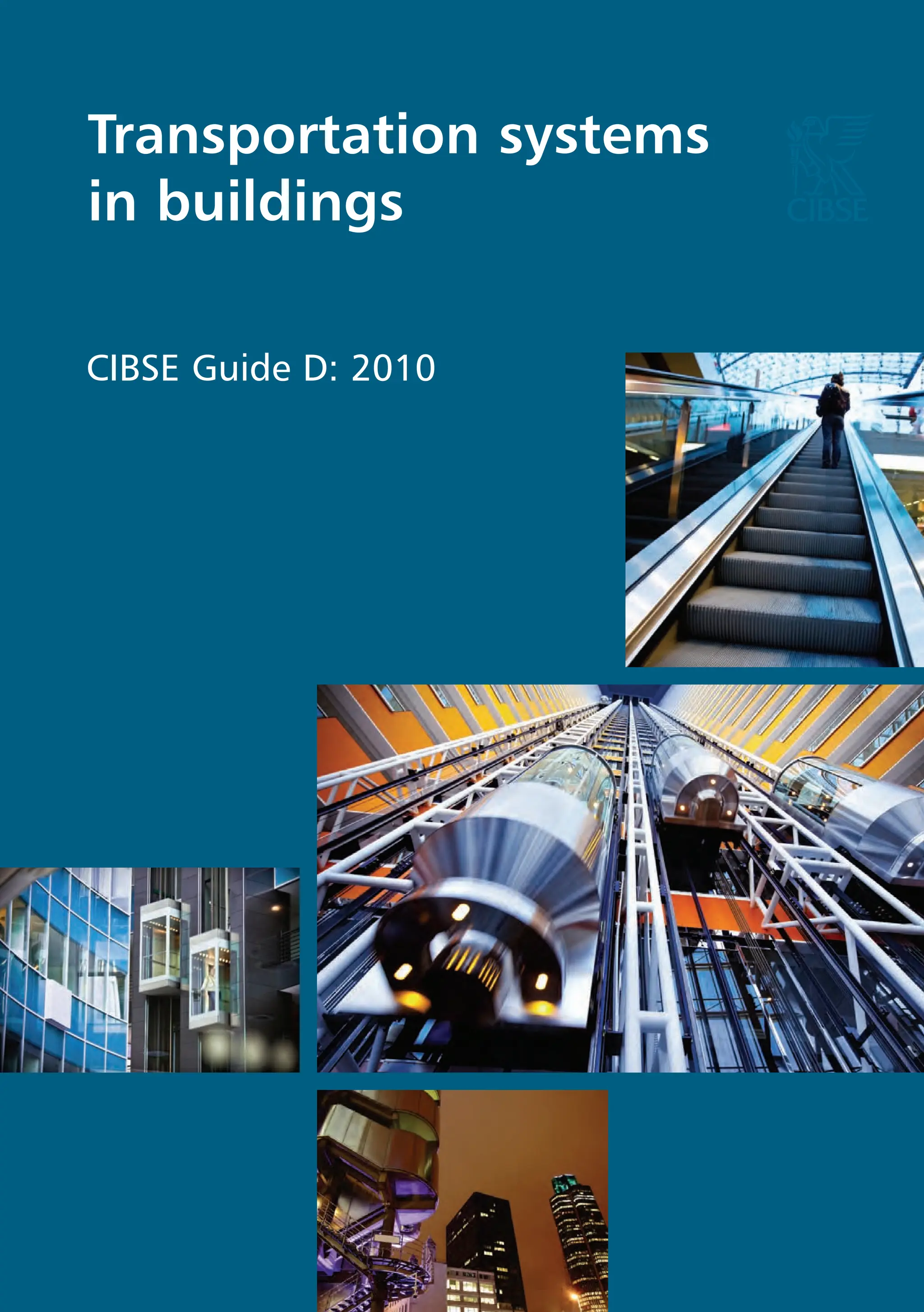

Guide D Transportation Systems In Buildings 2010 Cibse Guide 4th Revised Edition Cibse

Guide D Transportation Systems In Buildings 2010 Cibse Guide 4th Revised Edition Cibse

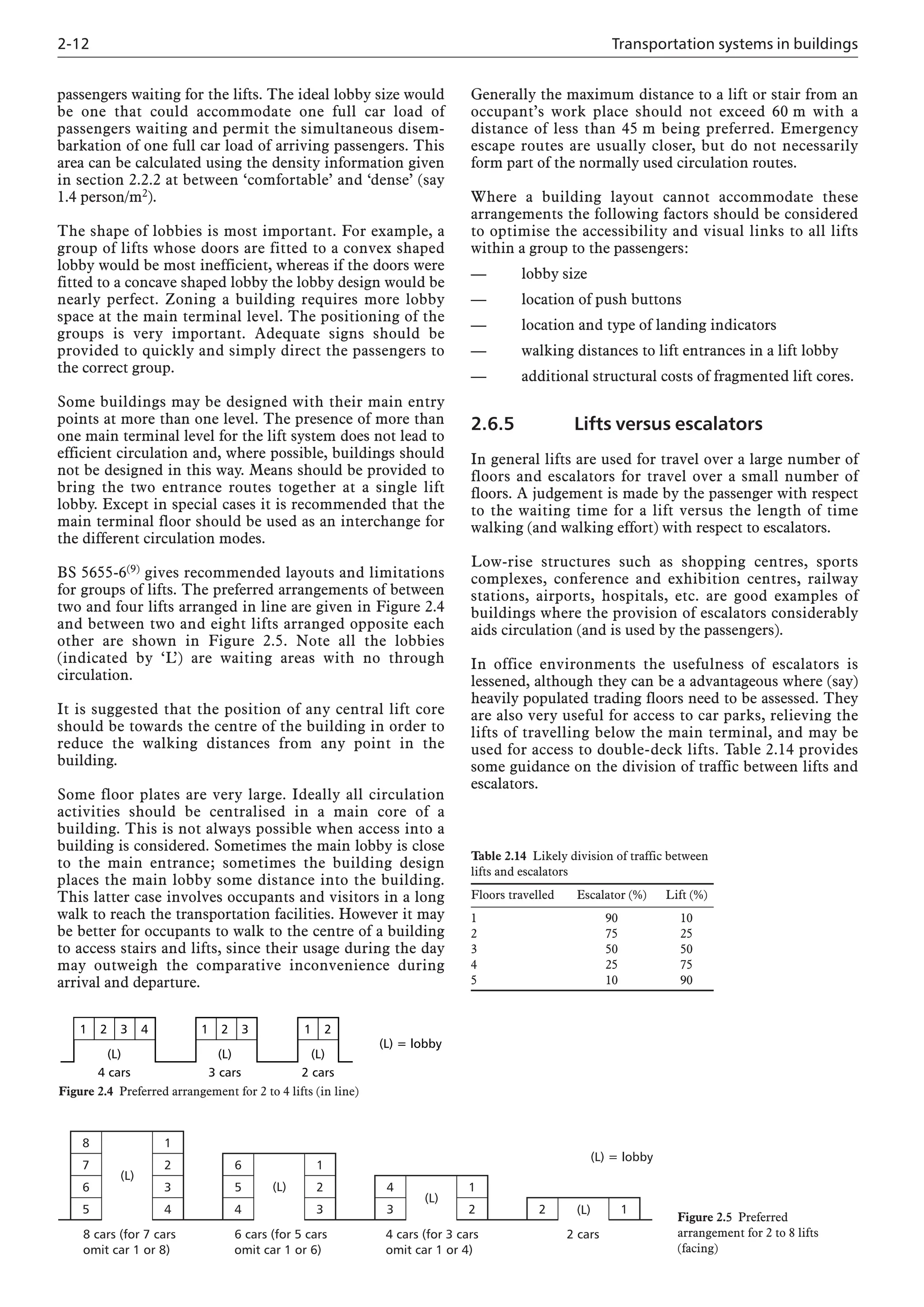

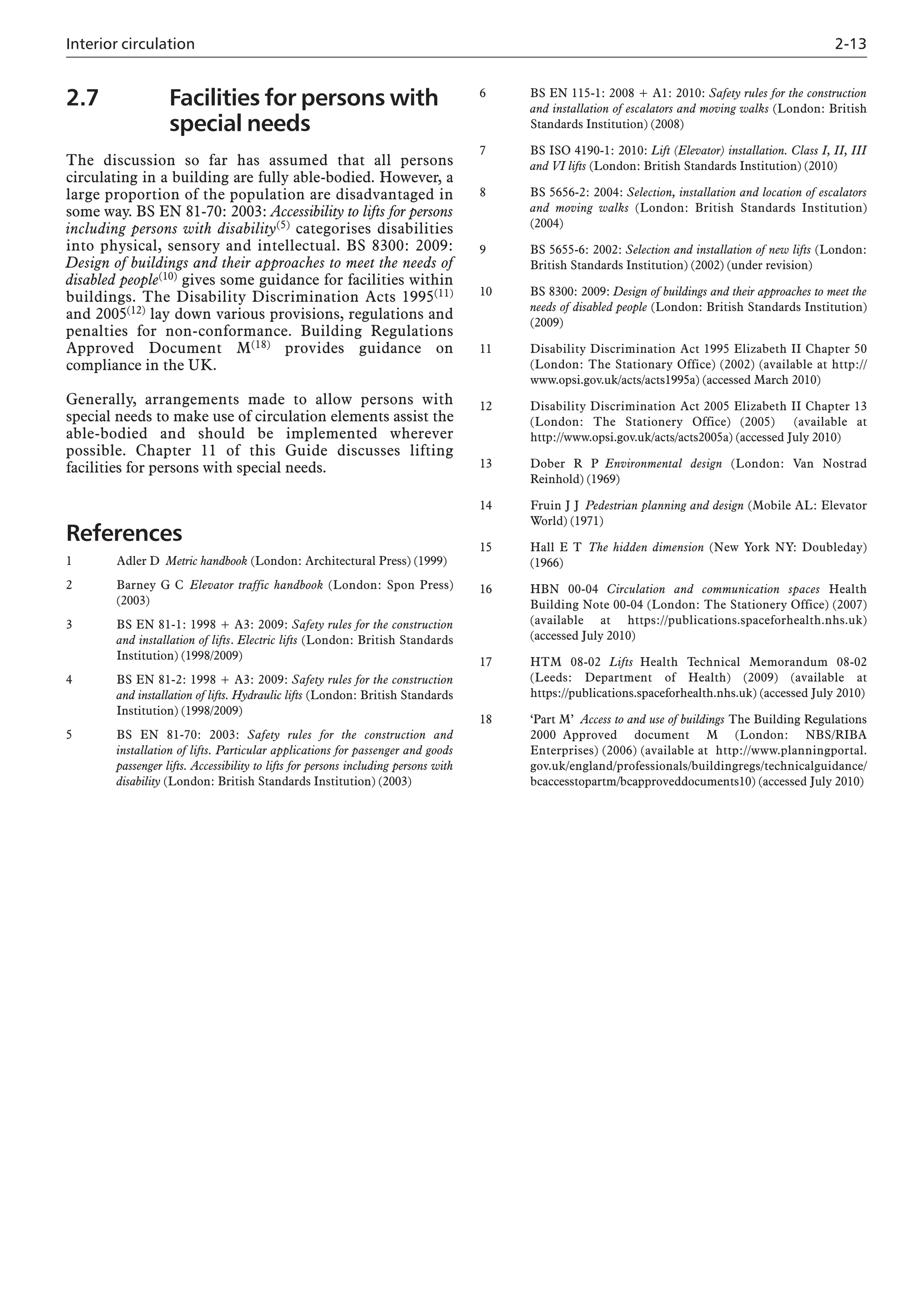

Guide D Transportation Systems In Buildings 2010 Cibse Guide 4th Revised Edition Cibse

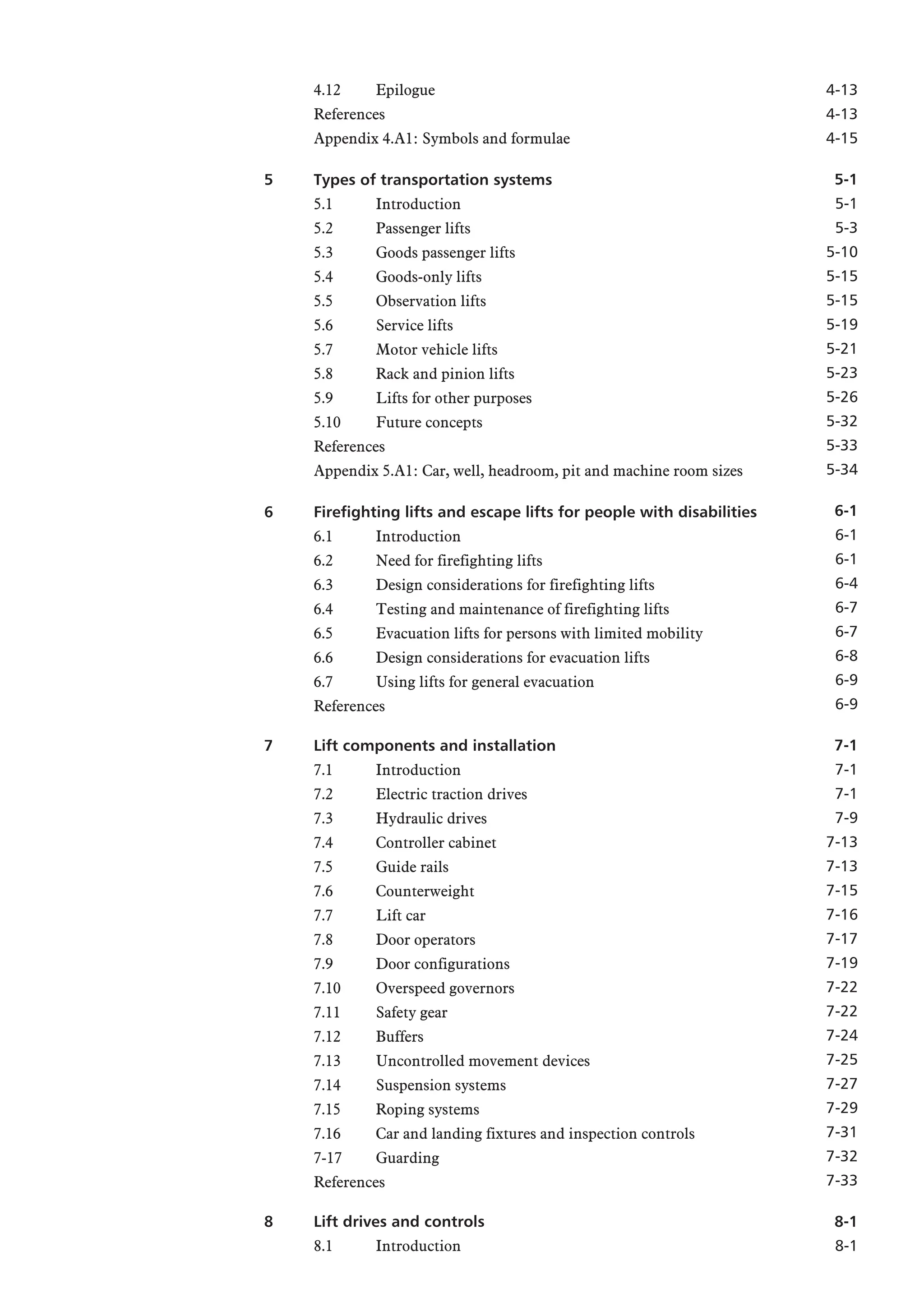

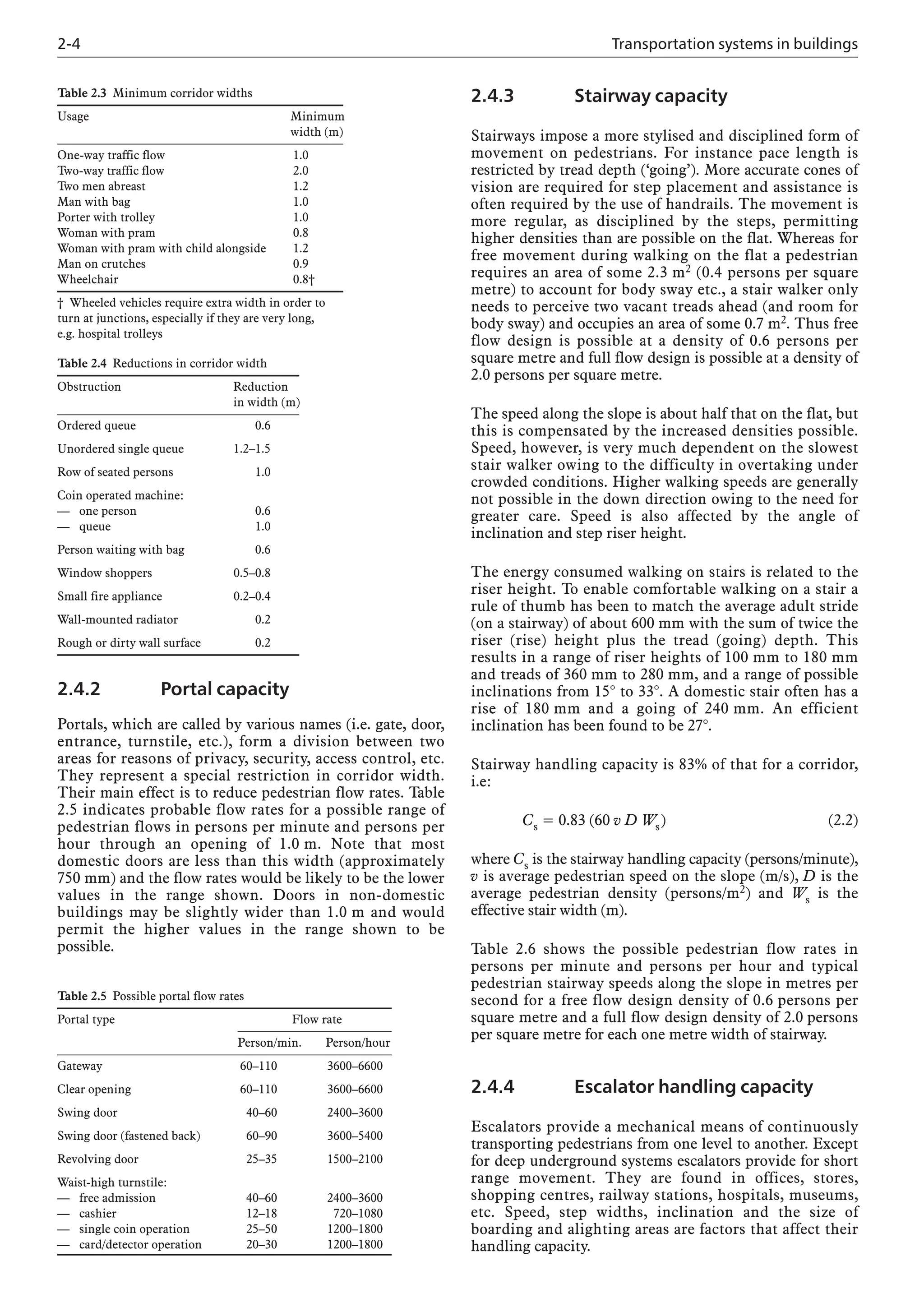

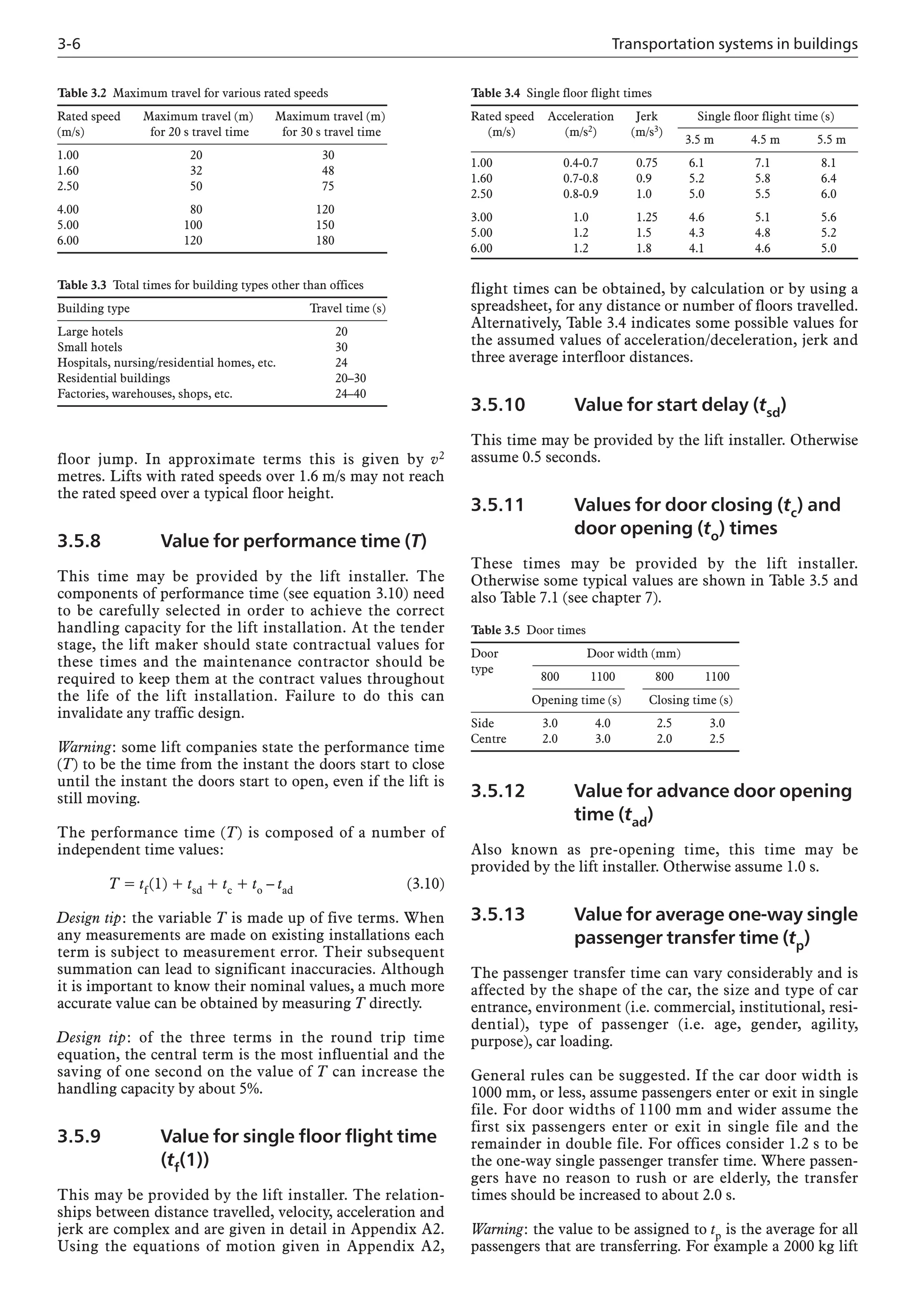

![Traffic planning and selection of lift equipment and performance 3-9

— Single floor flight time (tf(1)): 5.5 s

— Door close time (tc): 3.0 s

— Door open time (to): 2.0 s

— Advance door opening (tad): 1.0 s

— Start delay (tsd): 0.5 s

— Assumed one way passenger transfer time (tp): 1.0 s

Procedure:

(1) Enter data into cells B12, B13.

(2) From Table 3.1 select actual car capacity (11.4) and

the value for P (9.1) and enter into input cells B14,

B15. Note that results cells B30–B32 (P

, H, S) are

updated.

(3) Enter data into cells B16–19, B22–B27. Note

results cells B33–B38 (T, RTT, UPPINT, UPPHC,

%POP, %CF) are updated.

(4) Set input cells B20–B21 as zero.

(5) Adjust value of P in input cell B15 from 9.1 to 8.8

to achieve a %POP served of 12% in results cell B37.

Derived data:

— %POP = 12.0% (cell B37)

— UPPINT = 117.5 / 4 = 29.4 s (cell B35)

— RTT = 117.5 s (cell B34)

— UPPHC = 90.0 persons/5-minutes (cell B36)

Note: percentage capacity factor by area (results cell B38)

is 77%, which is slightly below the target of 80%.

Ignore results cells B39–B41, see sections 3.7.1, 3.9.1 and

3.9.2.

3.7 Passenger times during

up-peak traffic demand

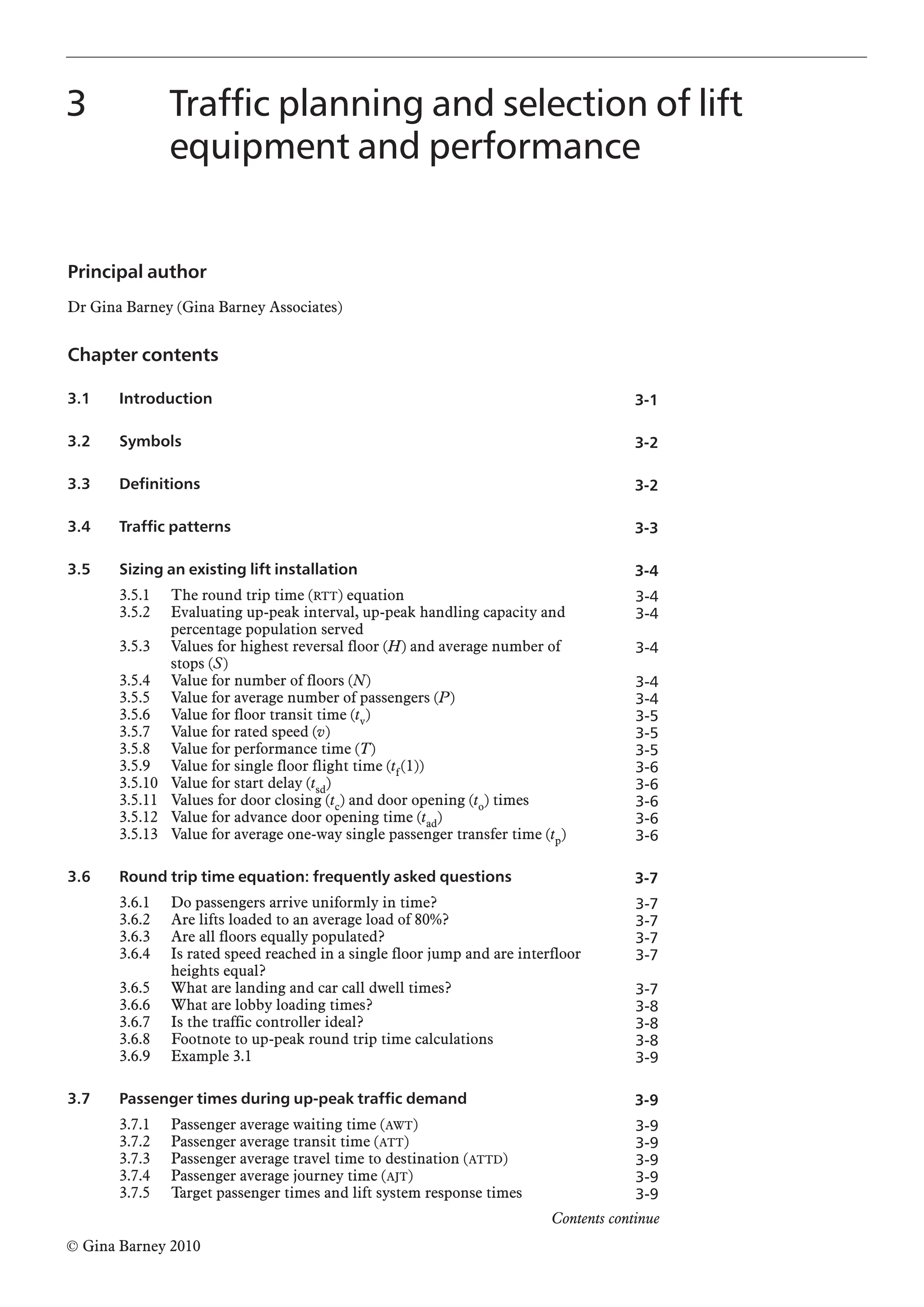

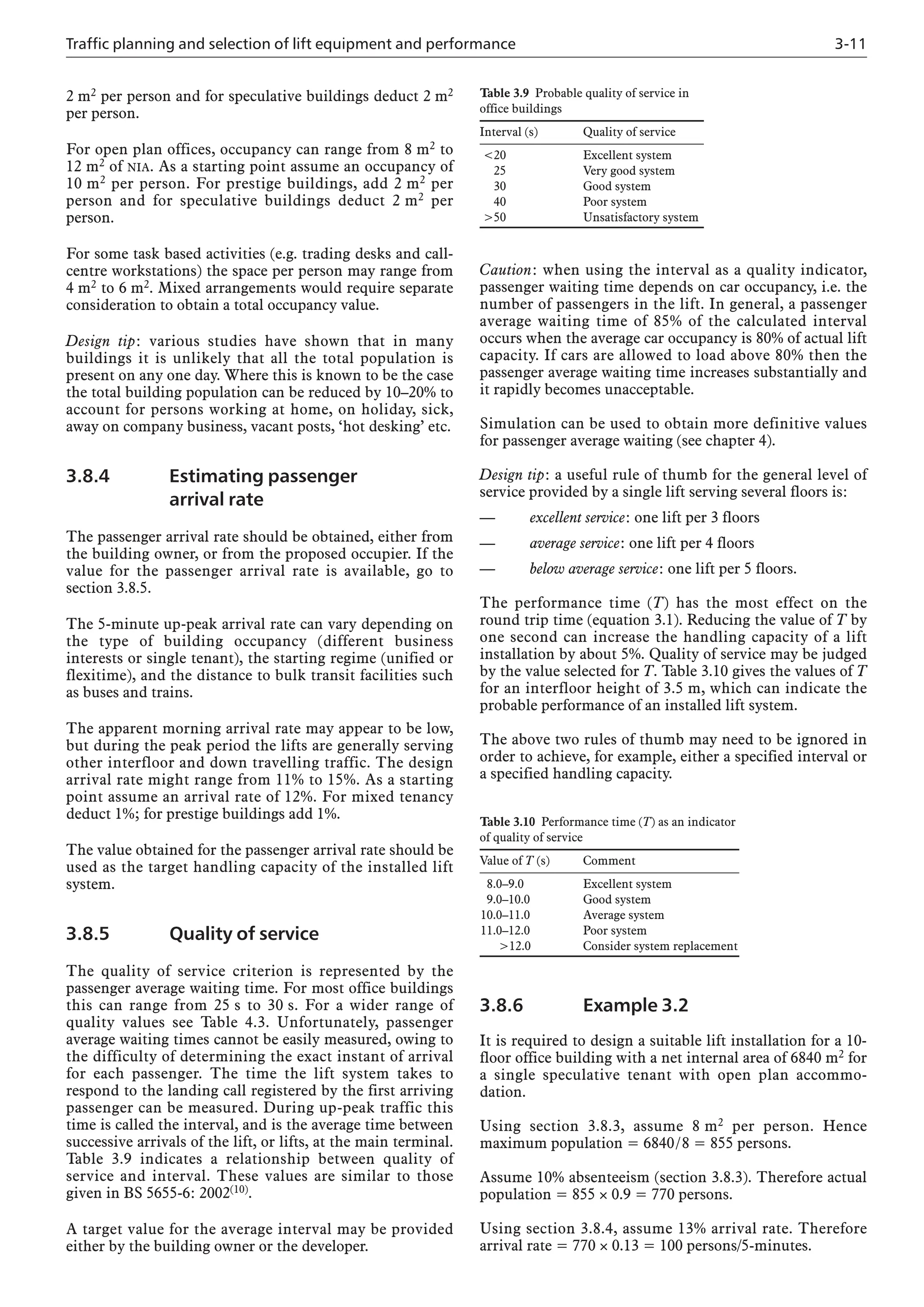

Figure 3.1 illustrates the relationships between the

passenger times.

Caution: all the formulae below are based on a math-

ematical model. To determine more accurate time values a

simulation study should be carried out, see chapter 4.

3.7.1 Passenger average waiting

time (AWT)

An equation can be derived for the passenger average

passenger waiting time(2g). For passenger loads (P) from

50% to 80% of rated capacity (CC), AWT is given by:

AWT = [0.4 + (1.8 P / CC – 0.77)2] INT (3.14)

For car loads less than 50%, AWT is 40% of the interval

(INT). Car loads above 80% are not considered.

On the spreadsheets for Examples 3.1 and 3.3 a value of

AWT is presented in cell B39.

Caution: some lift companies state AWT as half the interval.

Others state incorrectly that the time for the lift to

respond to a first landing call registered, sometimes called

system response time (SRT), is the passenger average

waiting time. These times are often inaccurate as some lift

companies cancel the call registration as much as eight

seconds before the lift actually starts to open its doors at a

landing.

3.7.2 Passenger average transit

time (ATT)(2h)

An estimate of how long it takes the average passenger to

reach their destination whilst in the car is obtained by

calculating ATT to the midpoint of the local travel for any

group of lifts. This implies travel for a distance of H/2

with the number of stops being S/2 and a transfer of P

passengers boarding the lift and P/2 passengers alighting

before the average passenger alights. The formula is:

ATT = 0.5 H tv + 0.5 S ts + 1.5 P tp (3.15)

3.7.3 Passenger average travel time to

destination (ATTD)(2i)

The average time it would take for an average passenger to

reach their destination floor is obtained by adding the

primary physiological consideration of average passenger

waiting time (AWT) to the secondary physiological

consideration of average passenger transit time (ATT) to

give a average passenger time to destination (ATTD). The

formula is:

ATT = 0.5 H tv + 0.5 S ts + 1.5 P tp+ AWT (3.16)

3.7.4 Passenger average journey

time (AJT)

This is longer than the passenger average travel time to

destination (ATTD) by the time required to open the lift

doors and the passenger to cross the threshold.

3.7.5 Target passenger times and lift

system response times

To achieve satisfactory passenger experiences the target

times shown in Table 3.7 are recommended.

The times indicated in Table 3.7 can be calculated, but

more reliable values may be obtained by simulation.

The grade of service provided by an installed lift system in

an office building can be expressed as either the

percentage of calls answered in specified time intervals, or

the time to answer a specified percentage of calls.

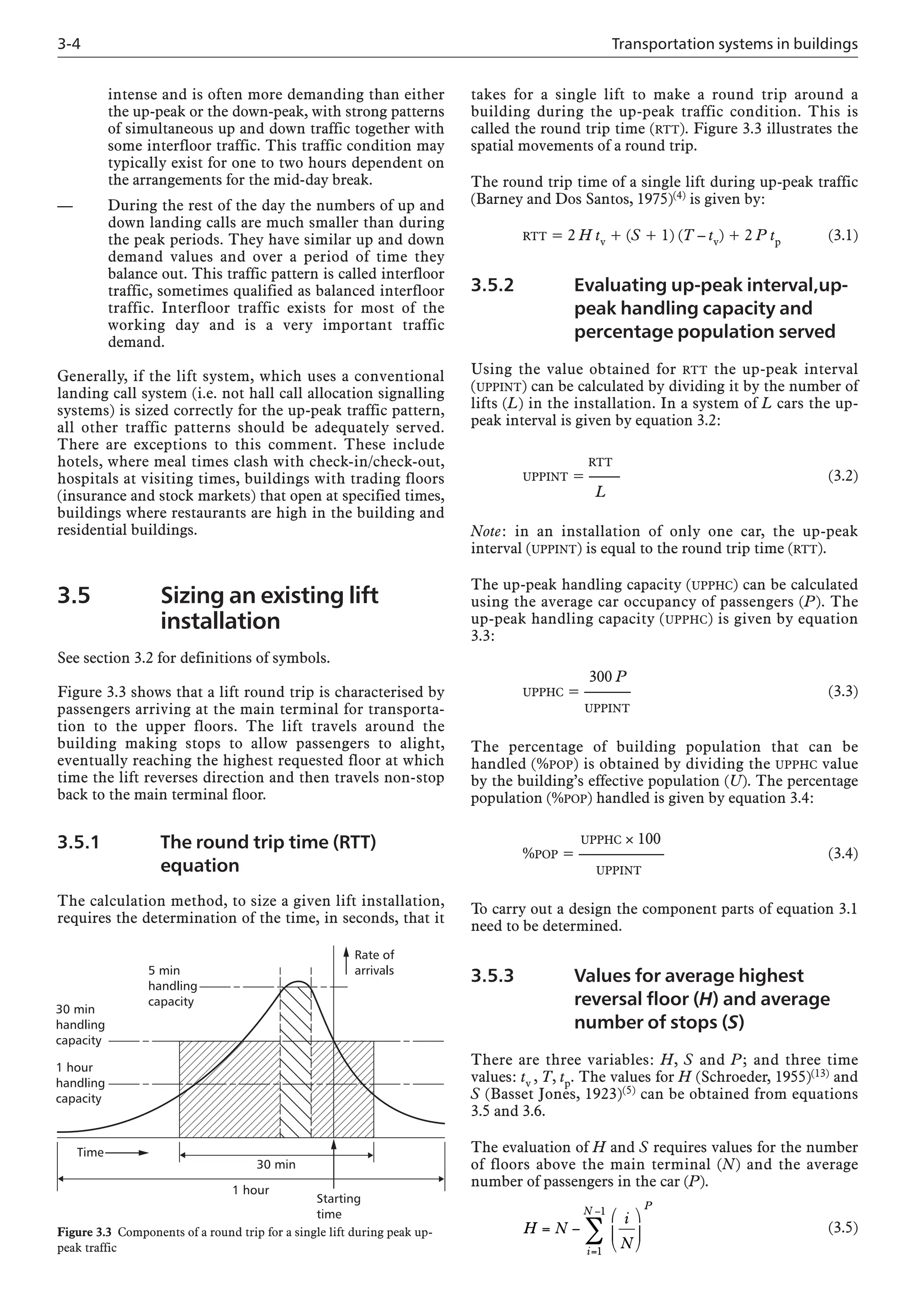

Table 3.7 Target passenger average times for office

buildings

Passenger time Target Poor

Average waiting time (AWT) <25 s >30 s

Average transit time (ATT) <60 s >70 s

Average journey time (AJT) <80 s > 90 s](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/16991071-250519033941-972a8df1/75/Guide-D-Transportation-Systems-In-Buildings-2010-Cibse-Guide-4th-Revised-Edition-Cibse-49-2048.jpg)

![This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United

States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away

or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License

included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the

laws of the country where you are located before using this

eBook.

Title: Johnny Ludlow, Second Series

Author: Mrs. Henry Wood

Release date: October 3, 2012 [eBook #40928]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by David Edwards, eagkw, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously

made available by Internet Archive (http://archive.org)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JOHNNY

LUDLOW, SECOND SERIES ***](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/16991071-250519033941-972a8df1/75/Guide-D-Transportation-Systems-In-Buildings-2010-Cibse-Guide-4th-Revised-Edition-Cibse-60-2048.jpg)