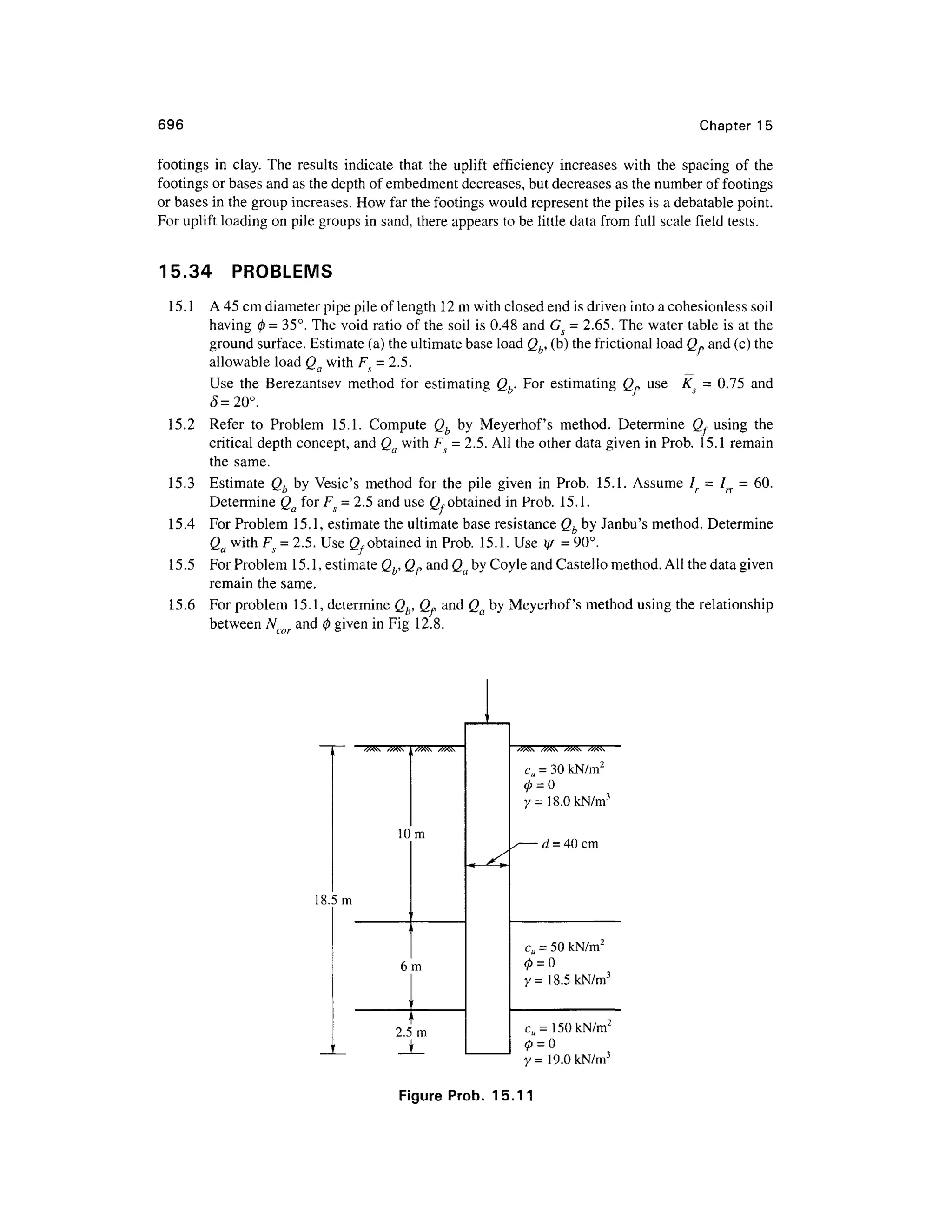

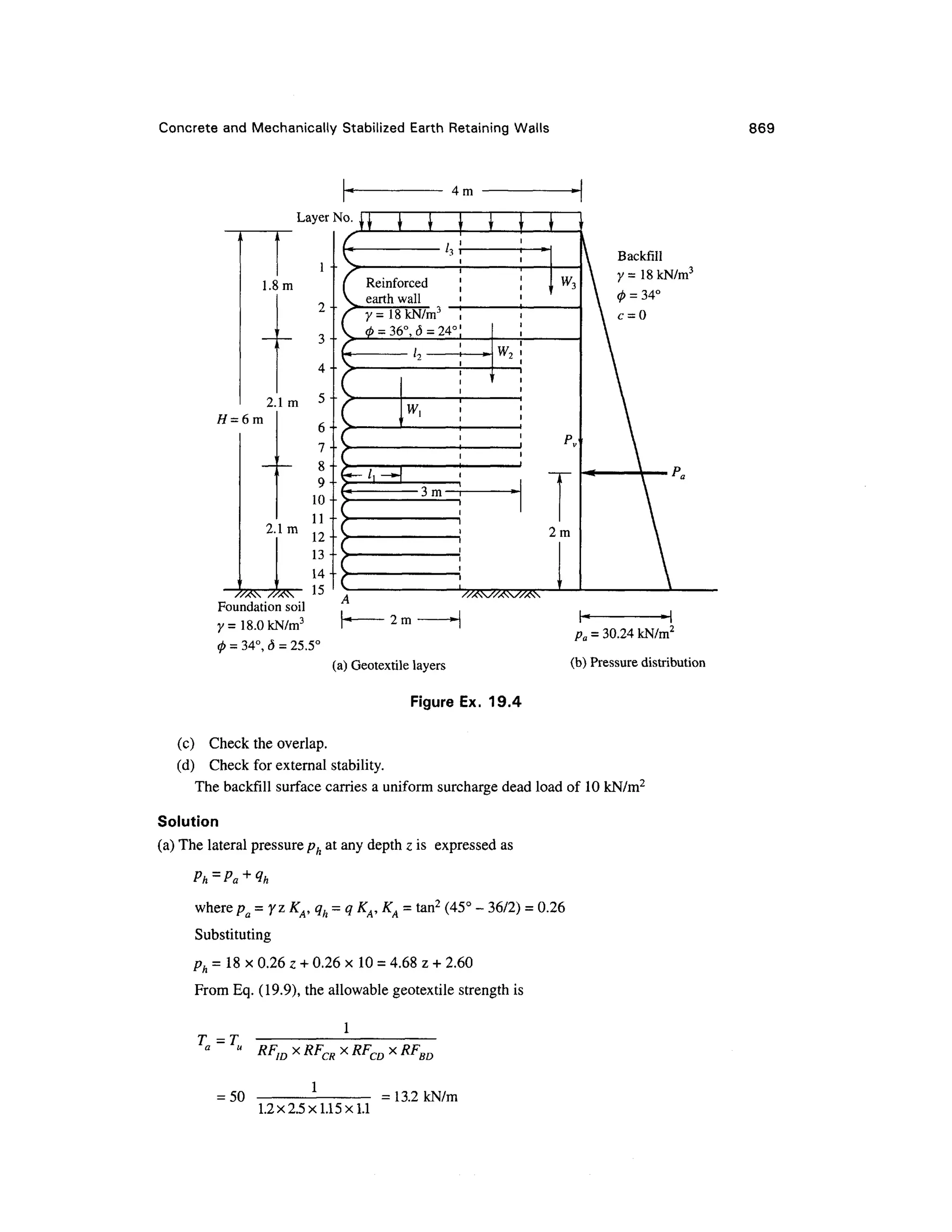

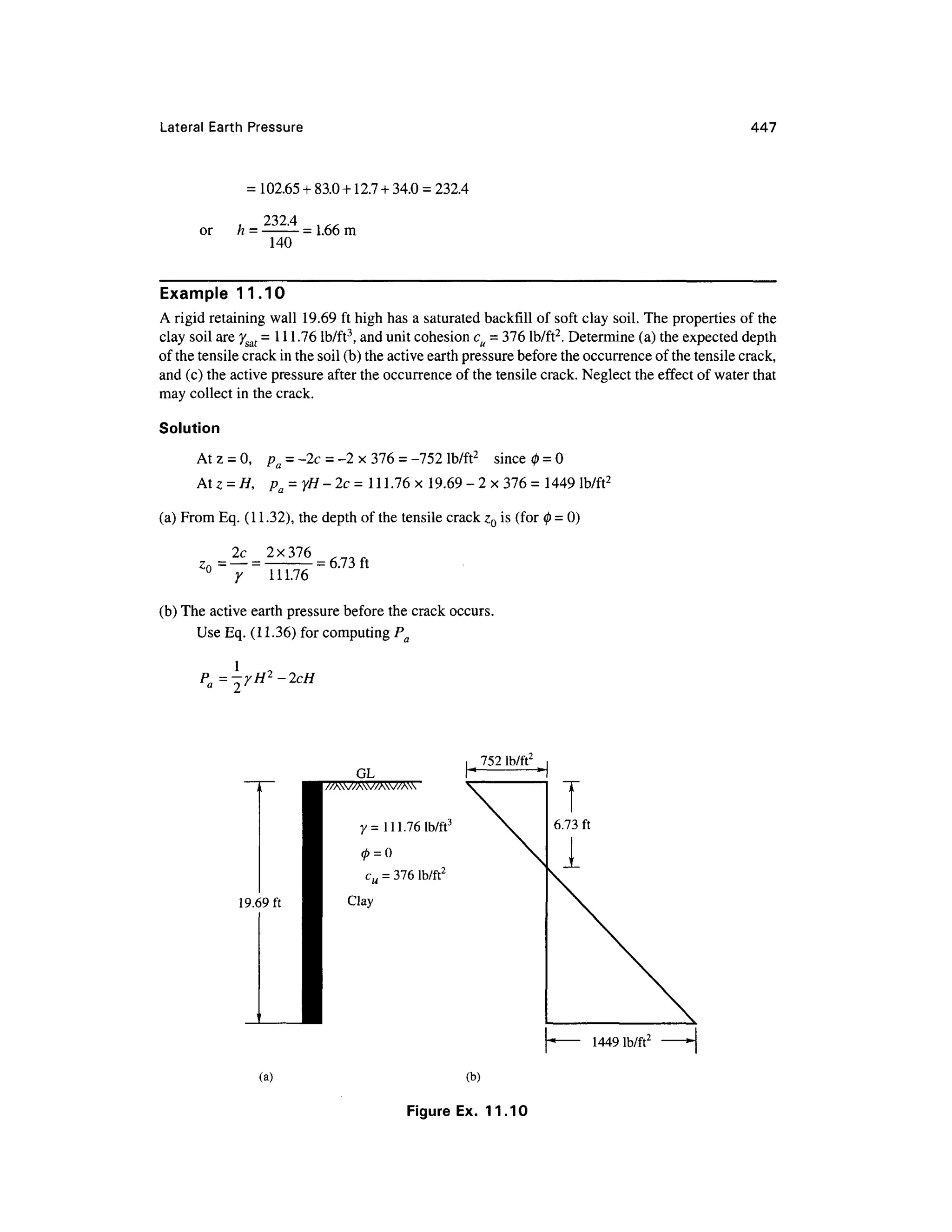

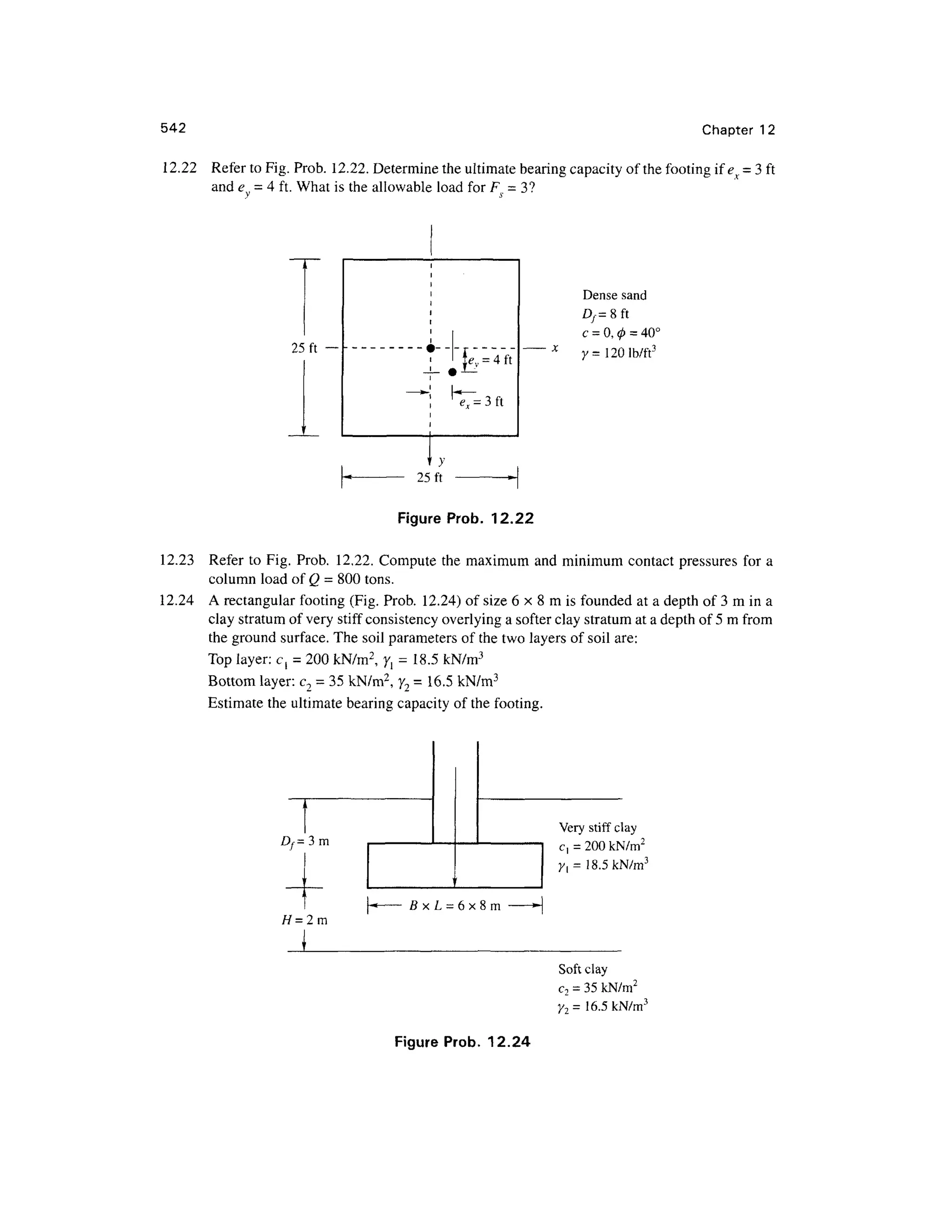

This document provides a summary and introduction to a textbook on geotechnical engineering. It discusses the comprehensive nature and logical organization of the textbook. It provides endorsements from two professors who praise the coverage, clarity, and insights provided in the textbook. They believe the textbook will be well-received and serve as a valuable reference for students, professors, and engineers. The forewords provide a high-level endorsement of the textbook's suitability and comprehensive treatment of the subject matter.

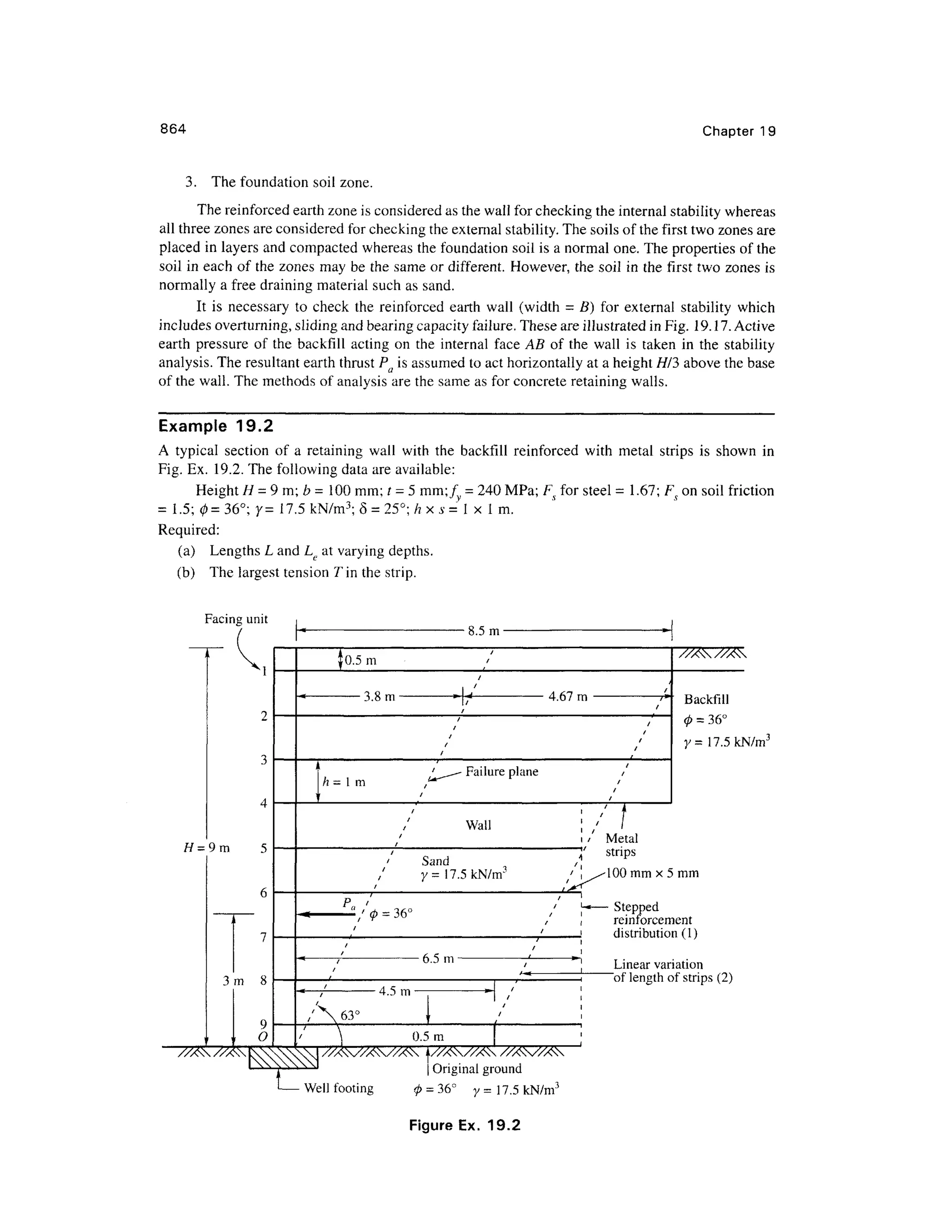

![1 2 Chapter 2

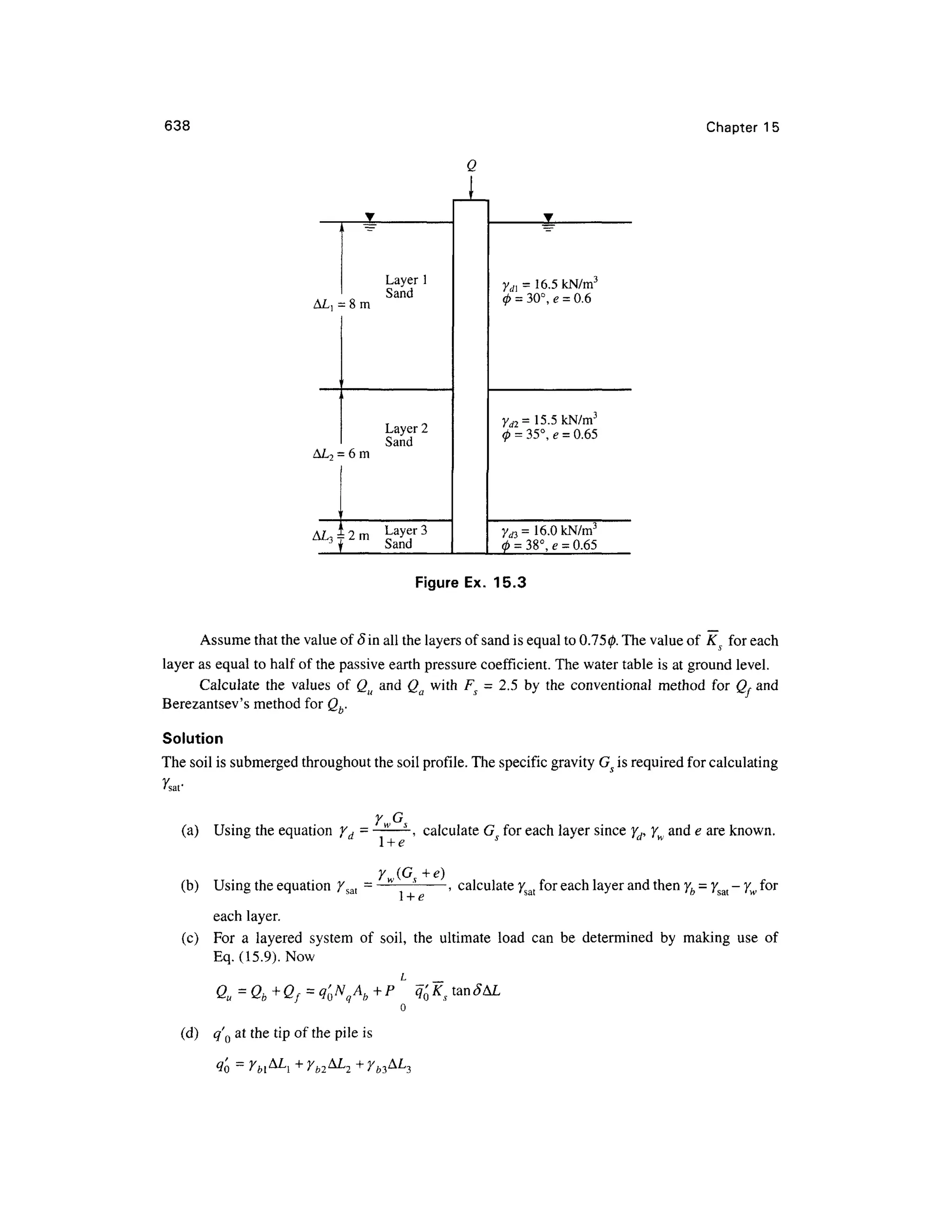

adjacent tetrahedra l unit . The sharin g of charge s leave s thre e negativ e charge s a t th e bas e per

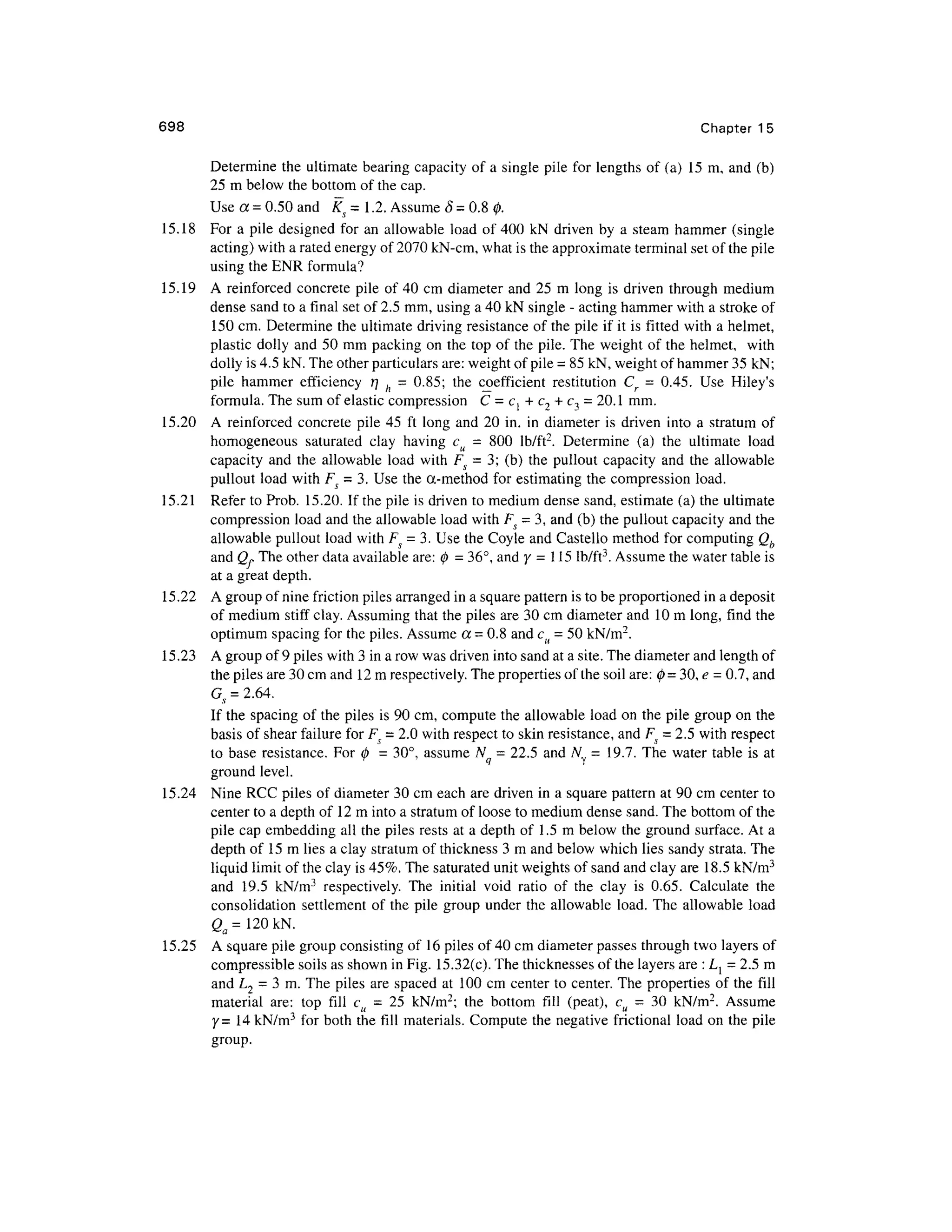

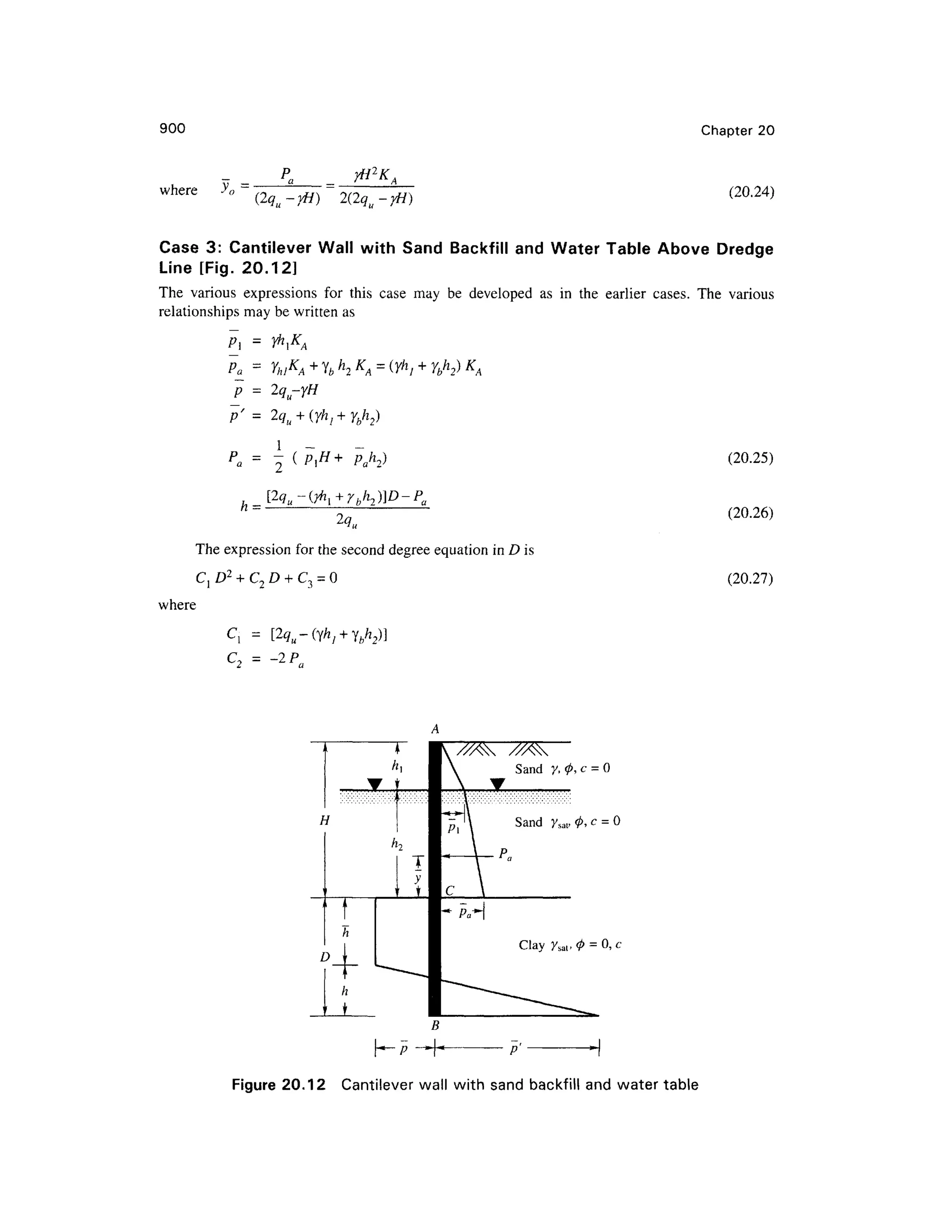

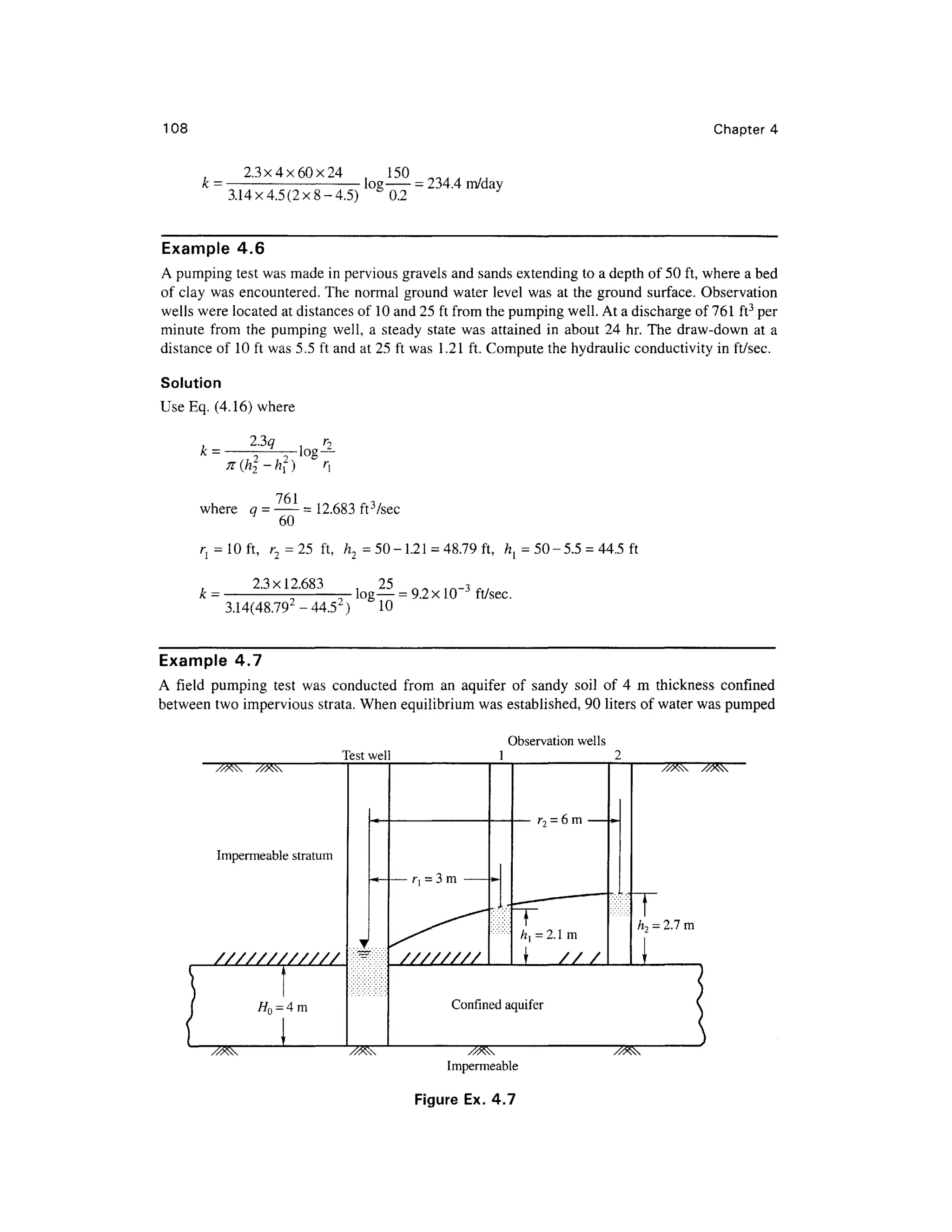

tetrahedral unit and this along with two negative charges at the apex makes a total of 5 negative

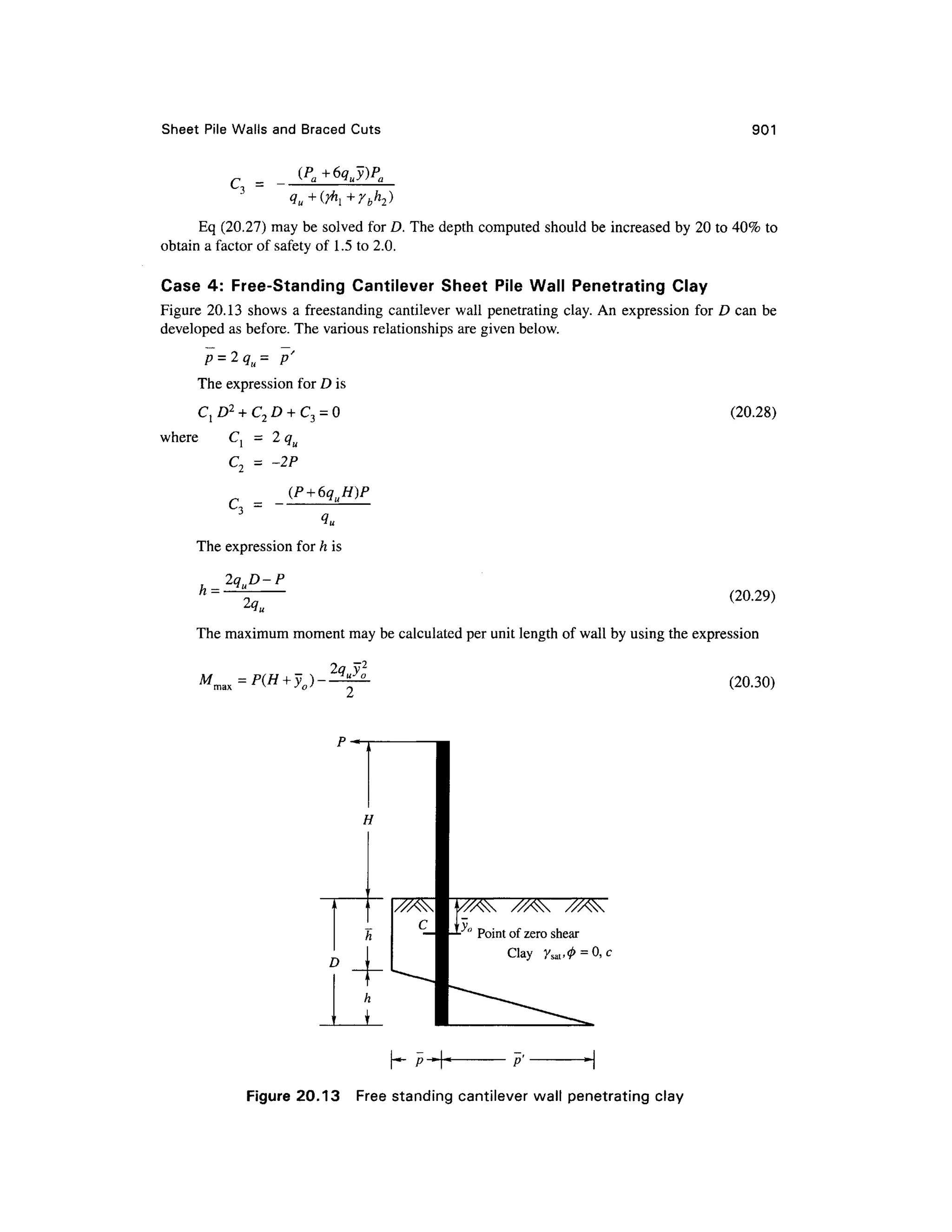

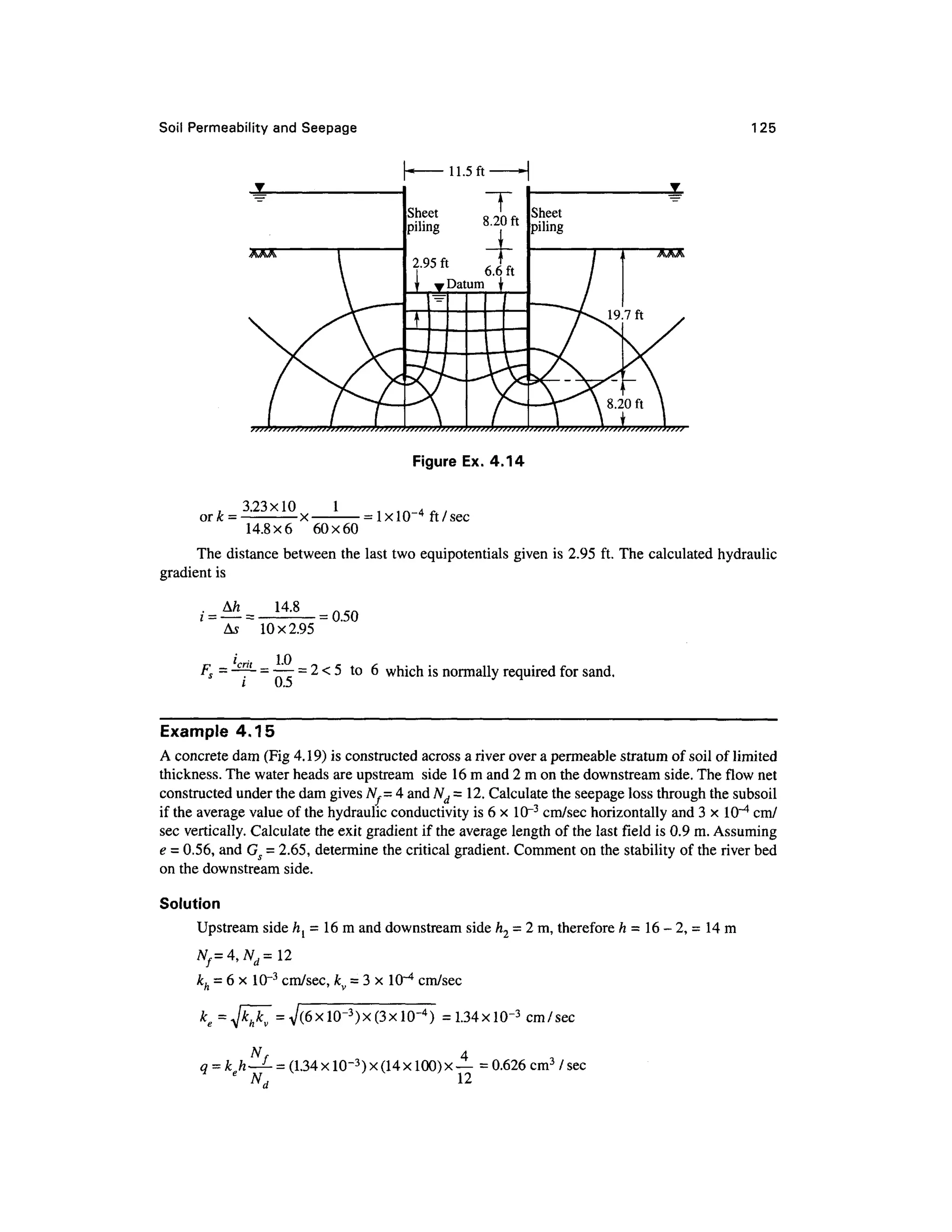

charges to balance the 4 positive charges of the silicon ion. The process of sharing the oxygen ions

at the base with neighboring units leaves a net charge of -1 per unit.

The second building block is an octahedral unit with six hydroxyl ions at apices of an octahedral

enclosing an aluminum ion at the center. Iron or magnesium ions may replace aluminum ions in some

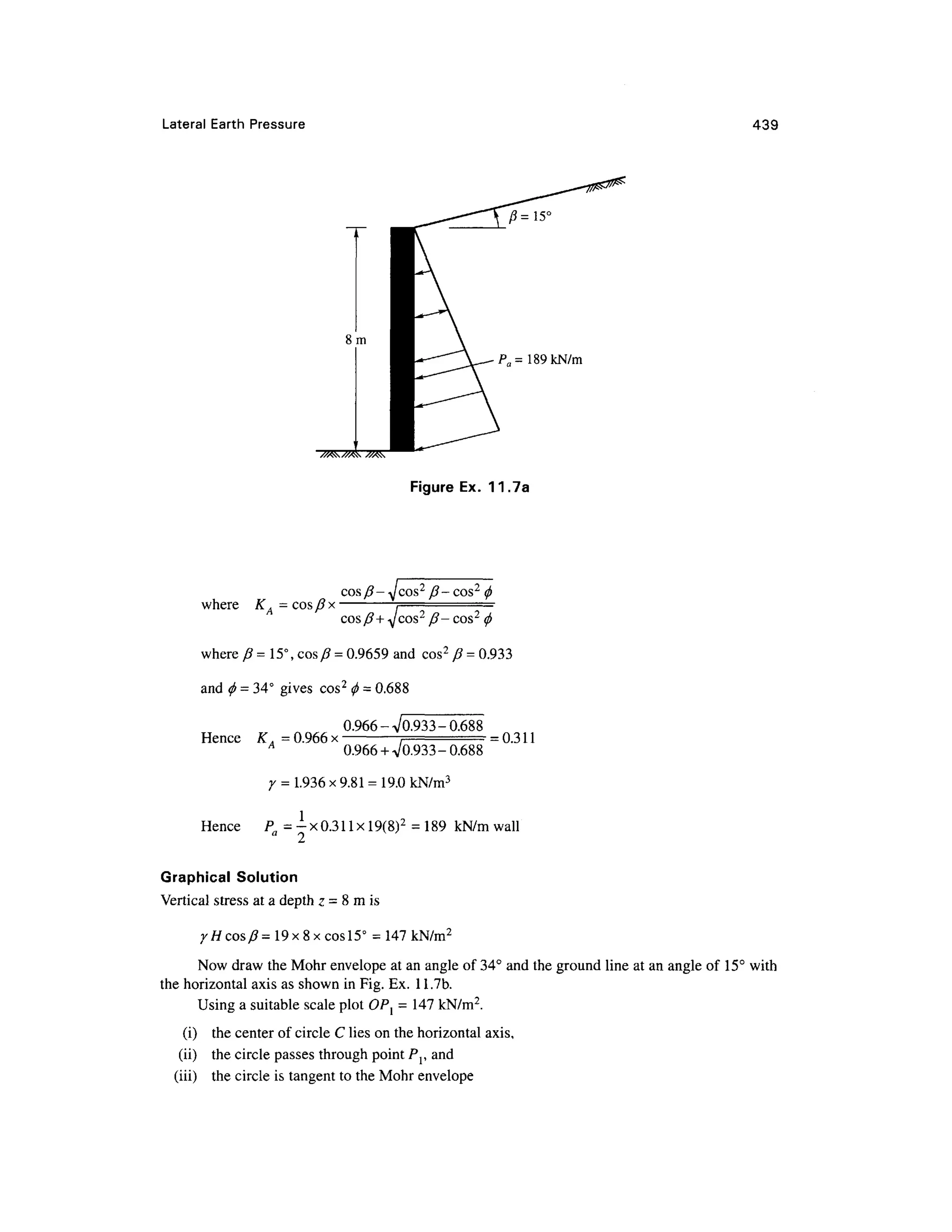

units. These octahedral units are bound together in a sheet structure with each hydroxyl ion common to

three octahedral units. This sheet is sometimes called as gibbsitesheet. The Al ion has 3 positive charges

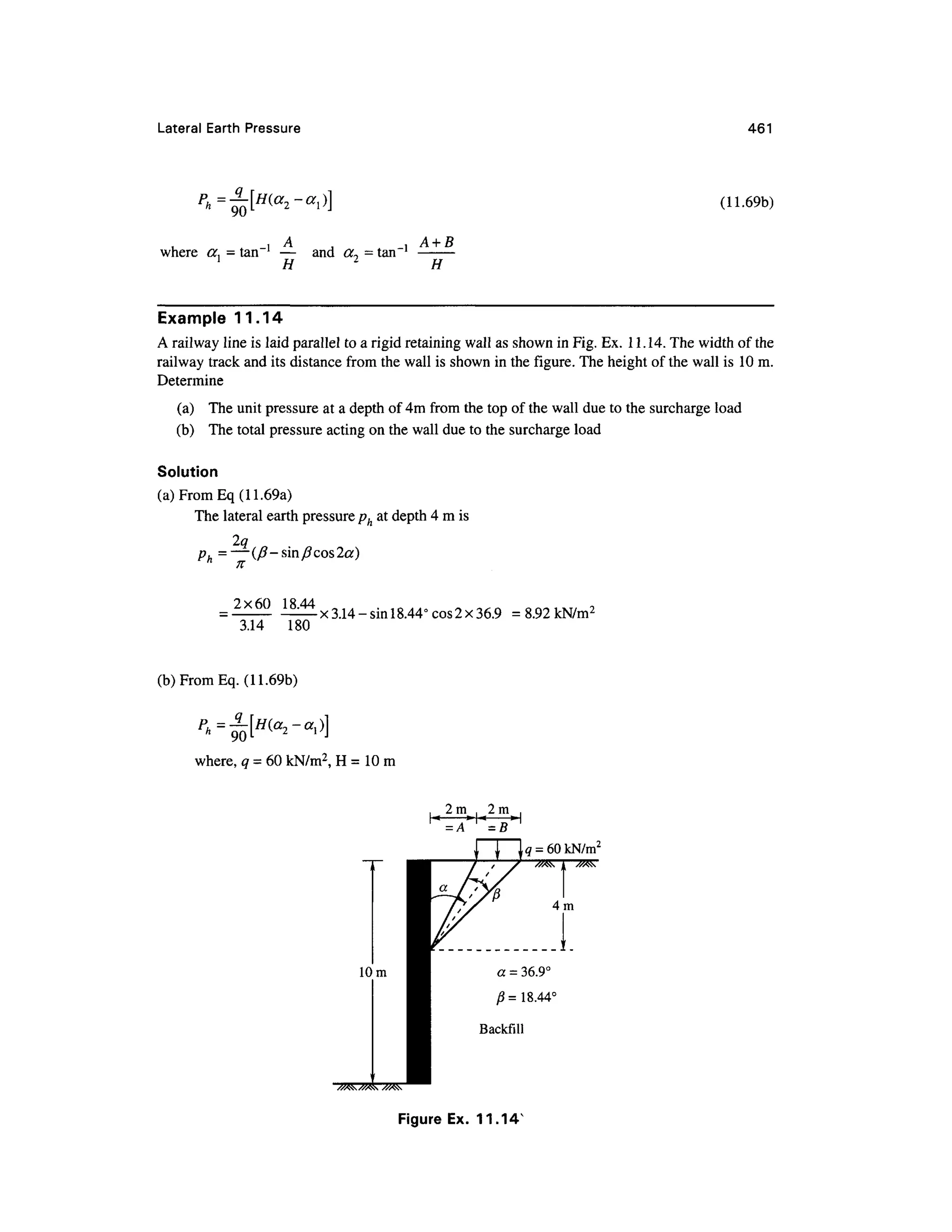

and each hydroxyl ion divides its -1 charg e with two other neighboring units. This sharing of negative

charge with other units leaves a total of 2 negative charges per unit [(1/3) x 6]. The net charge of a unit

with a n aluminu m ion a t th e cente r is +1 . Fig. 2. 3 give s th e structura l arrangements o f the units.

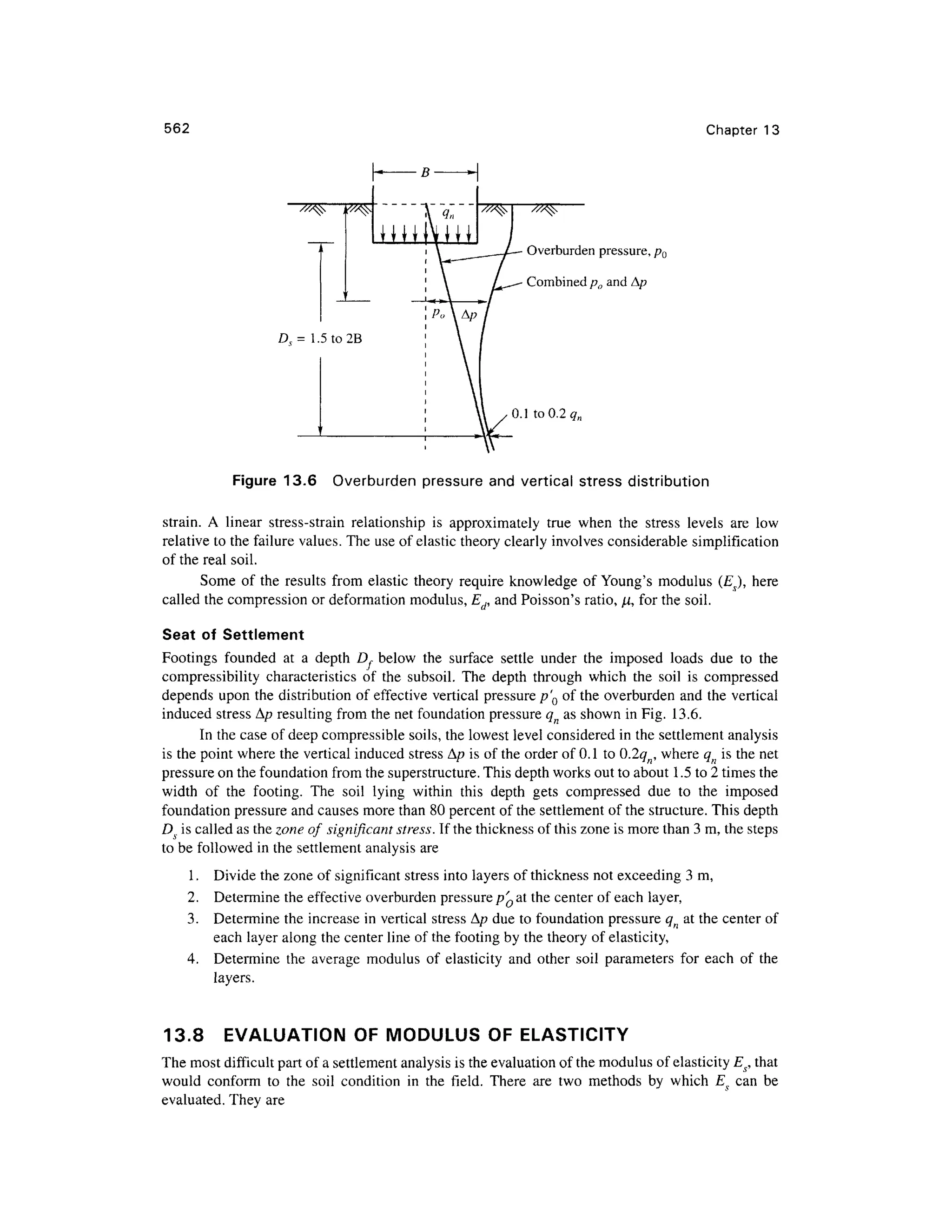

Sometimes, magnesiu m replaces th e aluminu m atoms i n th e octahedra l unit s in thi s case , th e

octahedral sheet is called a brucite sheet.

Formation o f Mineral s

The combination of two sheets of silica and gibbsite in different arrangement s and conditions lead

to the formation of different clay minerals as given in Table 2.3. In the actual formation of the sheet

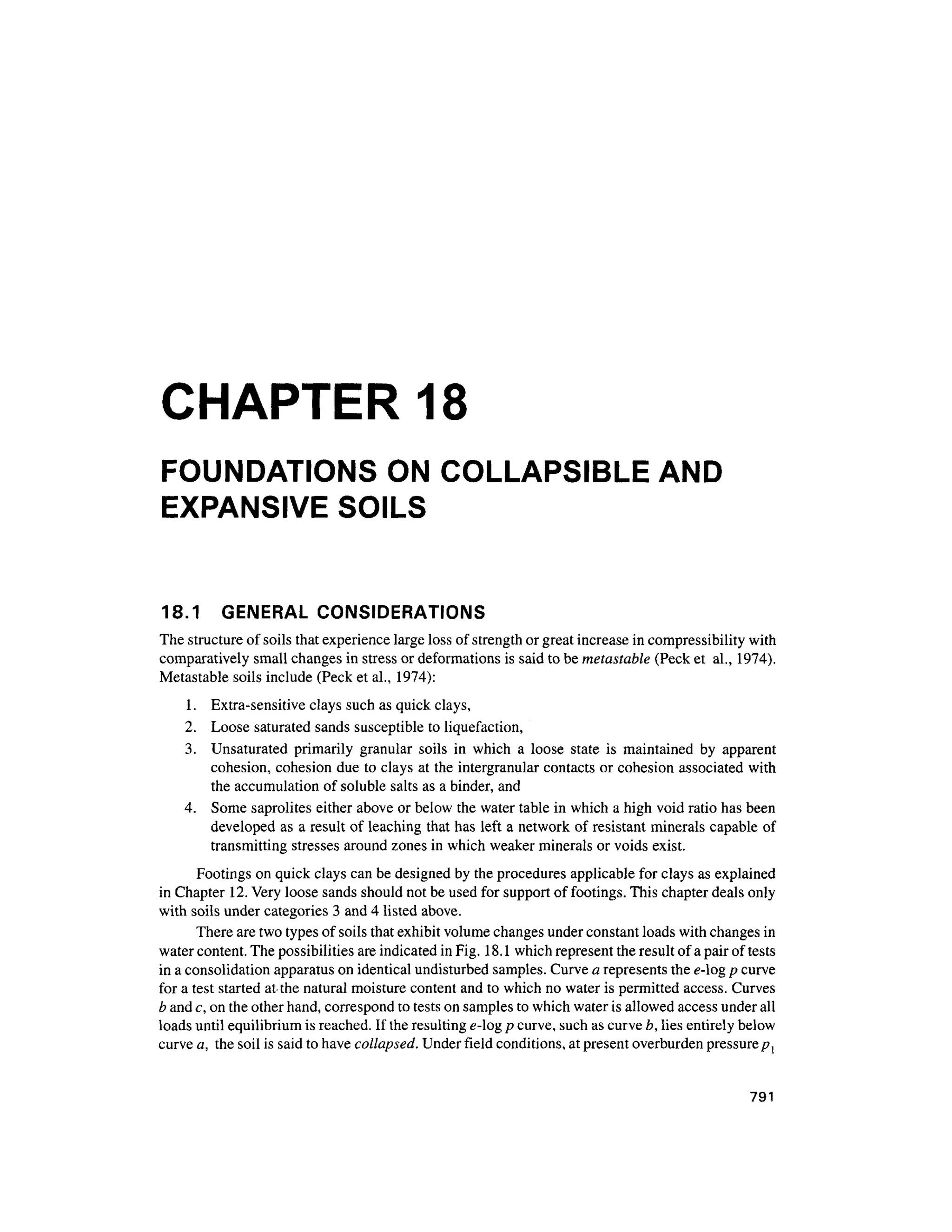

silicate minerals , the phenomenon of isomorphous substitution frequentl y occurs. Isomorphou s

(meaning same form) substitution consists of the substitution of one kind of atom for another.

Kaoiinite Minera l

This i s th e mos t commo n minera l o f th e kaoli n group . The buildin g blocks o f gibbsit e an d

silica sheets ar e arranged a s shown in Fig. 2.4 to give the structure of the kaolinite layer . The

structure i s compose d o f a singl e tetrahedra l shee t an d a singl e alumin a octahedra l shee t

combined i n unit s s o tha t th e tip s o f th e silic a tetrahedron s an d on e o f th e layer s o f th e

octahedral sheet form a common layer. All the tips of the silica tetrahedrons point in the same

direction and towards the center of the unit made of the silica and octahedral sheets. This gives

rise to strong ionic bonds between the silica and gibbsite sheets. The thickness of the layer is

about 7 A (on e angstro m = 10~ 8

cm) thick . The kaolinit e minera l i s formed b y stackin g th e

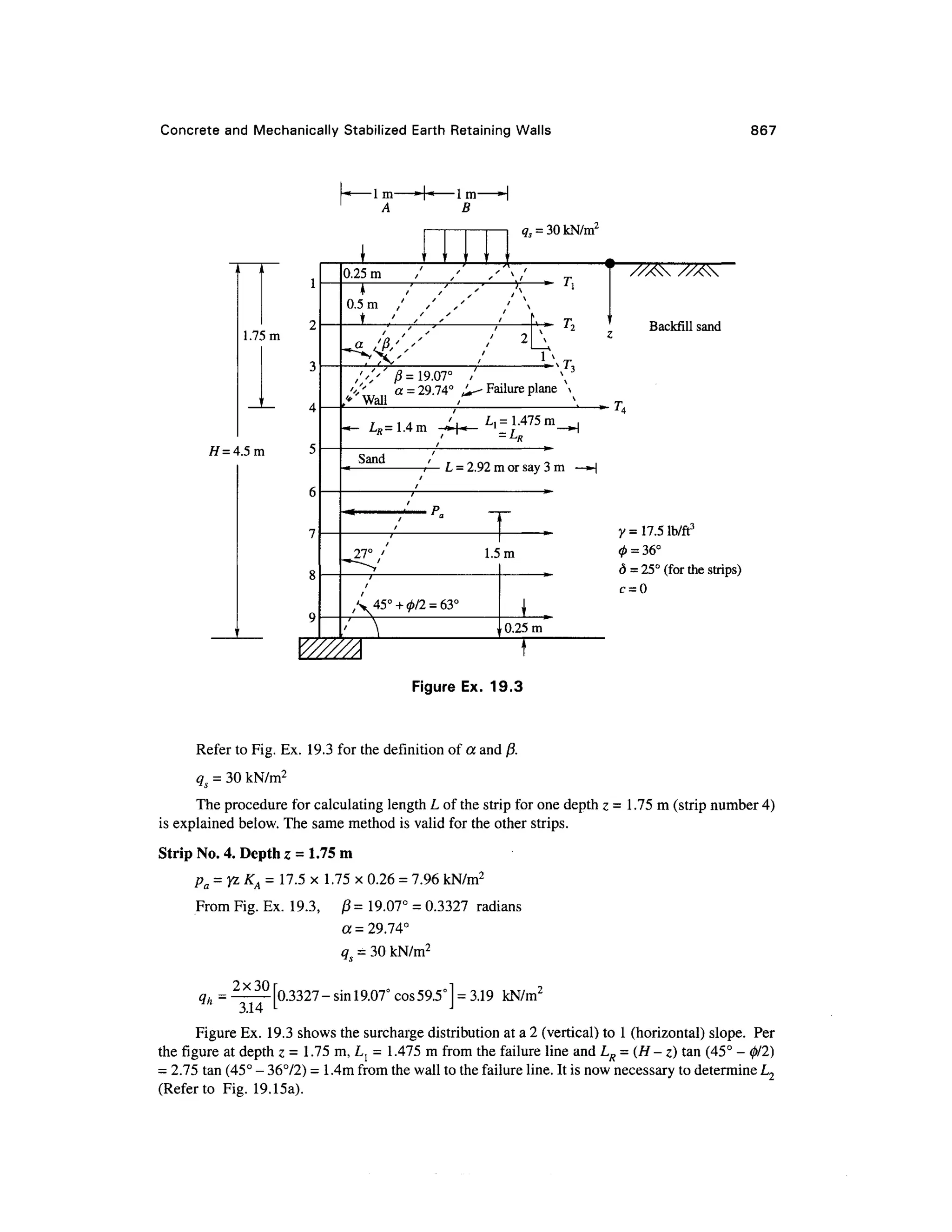

layers one above the other with the base of the silica sheet bonding to hydroxyls of the gibbsite

sheet b y hydroge n bonding . Sinc e hydroge n bond s ar e comparativel y strong , th e kaolinit e

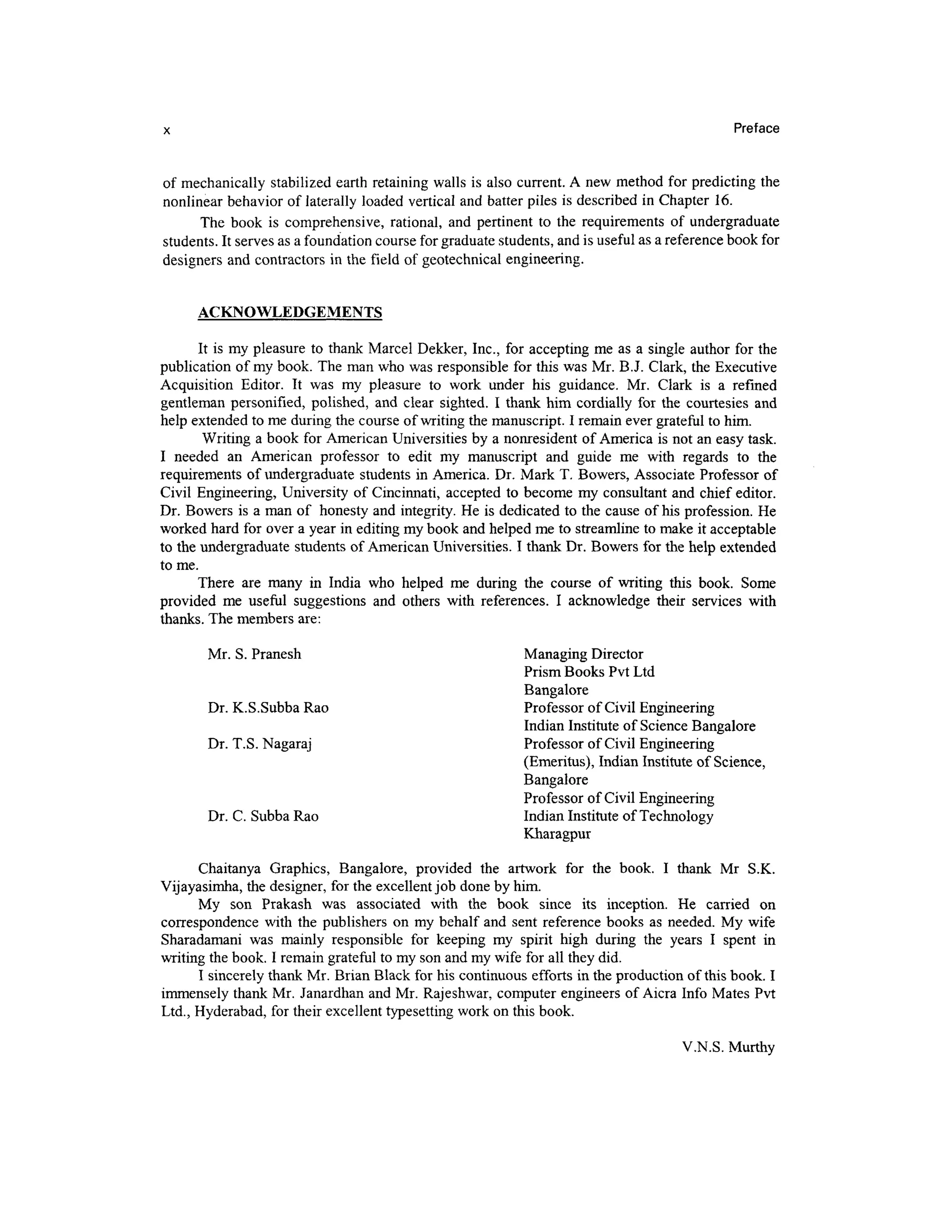

(a) Tetrahedral unit (b) Silica sheet

Silicons

Oxygen

]_ Symbolic representation

of a silica sheet

Figure 2.2 Basi c structural unit s in the silico n shee t (Grim , 1959 )](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-31-2048.jpg)

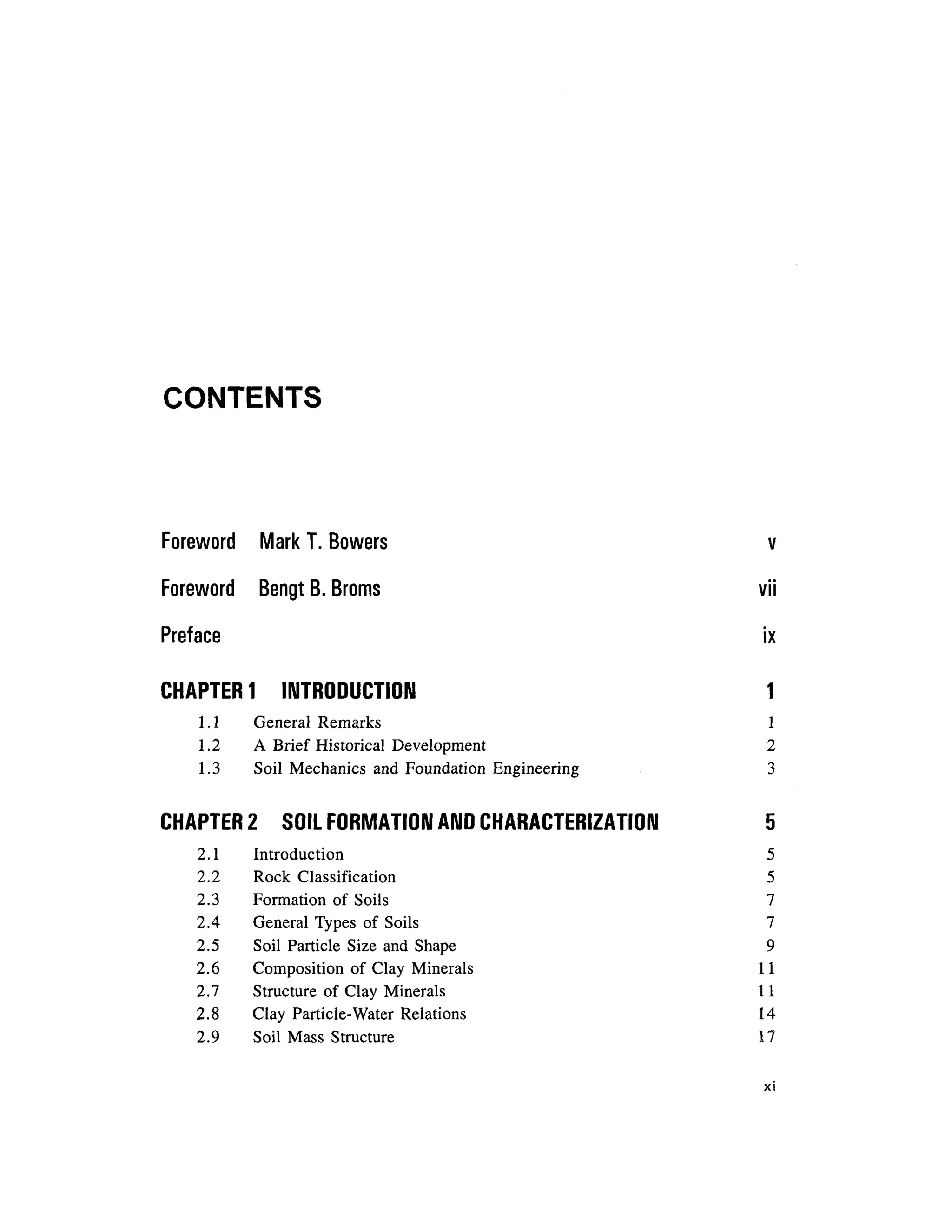

![Soil Phas e Relationships, Inde x Propertie s an d Soil Classificatio n 3 1

Example 3. 7

A soil sample has a total unit weight of 16.97 kN/m3

and a void ratio of 0.84. The specific gravity

of solids is 2.70. Determine the moisture content, dry unit weight and degree o f saturation of the

sample.

Solution

Degree of saturation [from Eq . (3.16a)]

= o r 1=

=

' l + e1 + 0.84

Dry unit weight (Eq. 3.18a)

d

l + e1 + 0.84

Water content (Eq. 3.14a1

Se 0.58x0.8 4 n i o

w- —= -

= 0.18 or 18 %

G 2. 7

Example 3. 8

A soil sample in its natural state has, when fully saturated, a water content of 32.5%. Determine the

void ratio, dry and total unit weights. Calculate the total weight of water required to saturate a soil

mass of volume 10 m3

. Assume G^ = 2.69.

Solution

Void ratio (Eq. 3.14a)

= ^

= 32.5 x2.69

S (l)xlO O

Total unit weight (Eq. 3.15a)

= . ) =

2*9 (9-81)0 +0323) = ,

' l + e1 + 0.874

Dry unit weight (Eq. 3.18a)

L&___ 2.69x9.8 1 = 14Q8kN/m3

d

l + e1 + 0.874

FromEq. (3.6a), W=ytV= 18.6 6 x10= 186.6 kN

From Eq . (3.7a), Ws = ydV= 14.0 8 x1 0 =140.8 kN

Weight of water =W-WS= 186. 6 - 140. 8 =45.8 kN

3.5 INDE X PROPERTIE S OF SOILS

The various properties of soils which would be considered as index properties are:

1 .Th e size and shape of particles.

2. Th e relative density or consistency of soil.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-50-2048.jpg)

![42 Chapter 3

1.65G

C = i —

58

2.65(G ? -1)

(3.31)

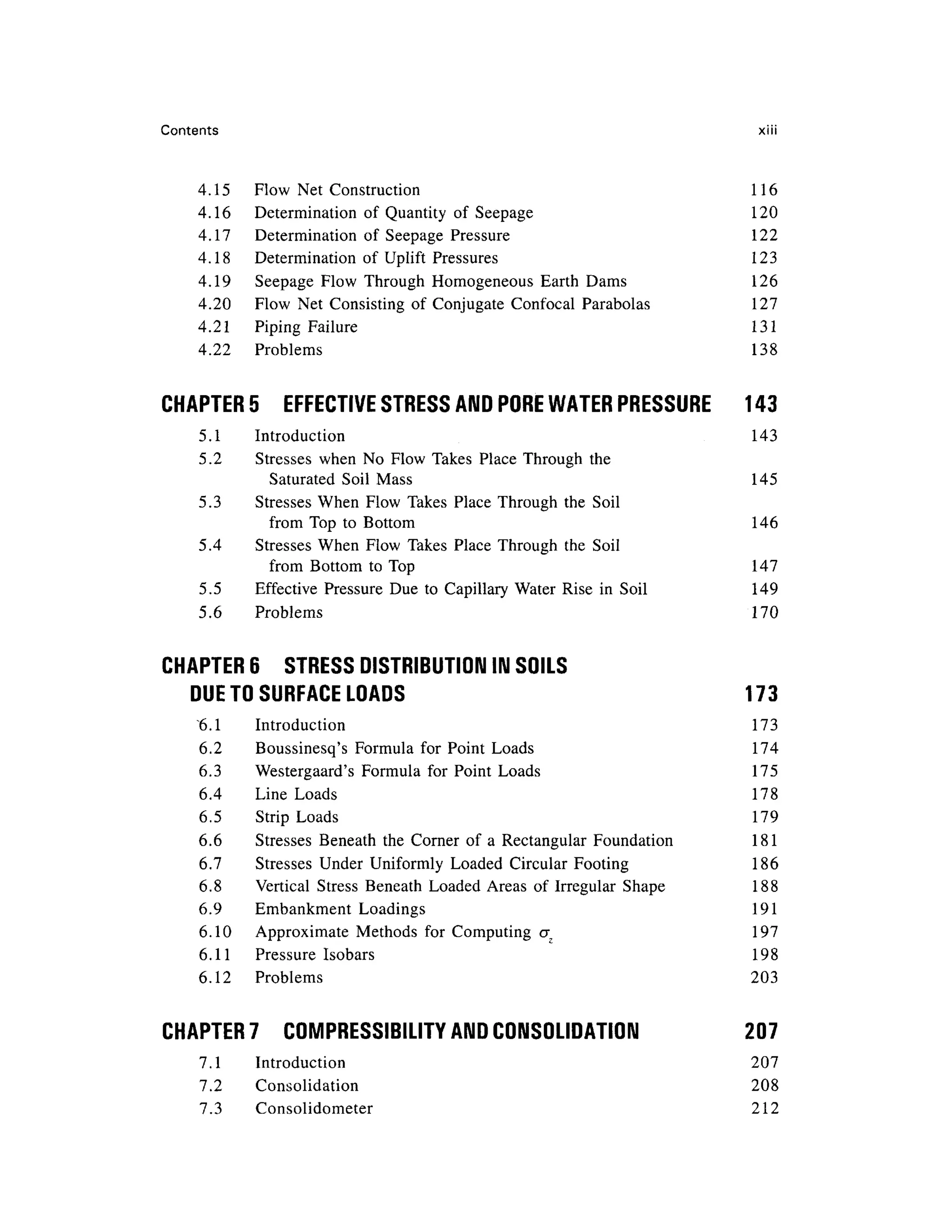

Typical values of C? ar e given in Table 3.7 .

Now the percent fine r with the correction factor Cs ma y be expressed a s

Percent finer, P ' =

M

xlOO (3.32)

where R c

= gram s o f soi l i n suspensio n a t som e elapse d tim e t [correcte d hydromete r

reading from Eq. (3.30b)]

Ms

= mas s o f soil used i n the suspension in gms (no t more tha n 60 gm for 15 2 H

hydrometer)

Eq. (3.32) gives the percentage of particles finer than a particle diameter D in the mass of

soil Ms use d in the suspension. If M i s the mass of soil particles passing through 75 micron siev e

(greater tha n M) an d M the total mass taken for the combined siev e and hydrometer analysis , the

percent fine r fo r the entire sample may be expressed a s

Percent finer(combined) , P = P'% x

M

(3.33)

Now Eq. (3.33) with Eq. (3.24) give s point s for plotting a grain size distributio n curve.

Test procedure

The suggeste d procedur e fo r conducting the hydrometer test is as follows:

1. Tak e 60 g or less dry sample fro m th e soil passing throug h the No. 200 siev e

2. Mi x thi s sample with 12 5 mL of a 4% of NaPO3 solution in a small evaporating dis h

3. Allo w the soil mixture to stand for about 1 hour. At the end of the soaking period transfer

the mixtur e to a dispersion cup an d add distilled water until th e cup i s about two-thirds

full. Mi x fo r about 2 min.

4. Afte r mixing, transfer all the contents of the dispersion cup to the sedimentation cylinder ,

being carefu l no t t o los e an y materia l Now ad d temperature-stabilize d wate r t o fil l th e

cylinder to the 100 0 m L mark.

5. Mi x th e suspension wel l by placing the palm of the hand over th e open en d an d turning

the cylinder upside down and back for a period of 1 min. Set the cylinder down on a table.

6. Star t th e time r immediatel y afte r settin g th e cylinder . Inser t th e hydromete r int o th e

suspension just abou t 2 0 second s befor e th e elapse d tim e o f 2 min . an d tak e th e firs t

reading a t 2 min . Tak e th e temperatur e reading . Remov e th e hydromete r an d th e

thermometer an d place both of them in the control jar.

7. Th e contro l jar contain s 100 0 m L o f temperature-stabilize d distille d water mixe d wit h

125 mL of the same 4% solution of NaPO3.

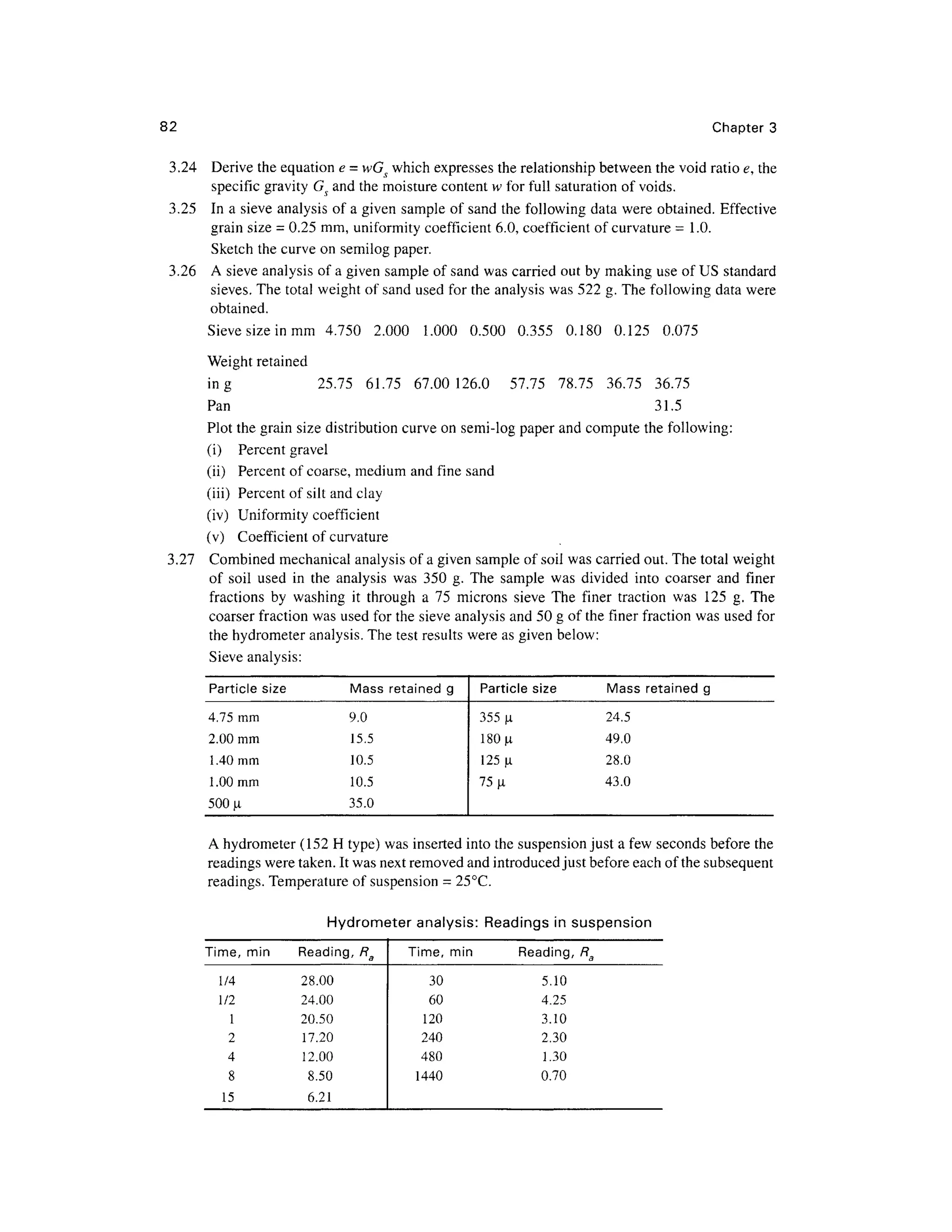

Table 3. 7 Correctio n factor s C fo r uni t weight o f solid s

Gs of soi l solids

2.85

2.80

2.75

2.70

Correction factor C

0.96

0.97

0.98

0.99

Gs of soi l solids

2.65

2.60

2.55

2.50

Correction factor C

1.00

1.01

1.02

1.04](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-61-2048.jpg)

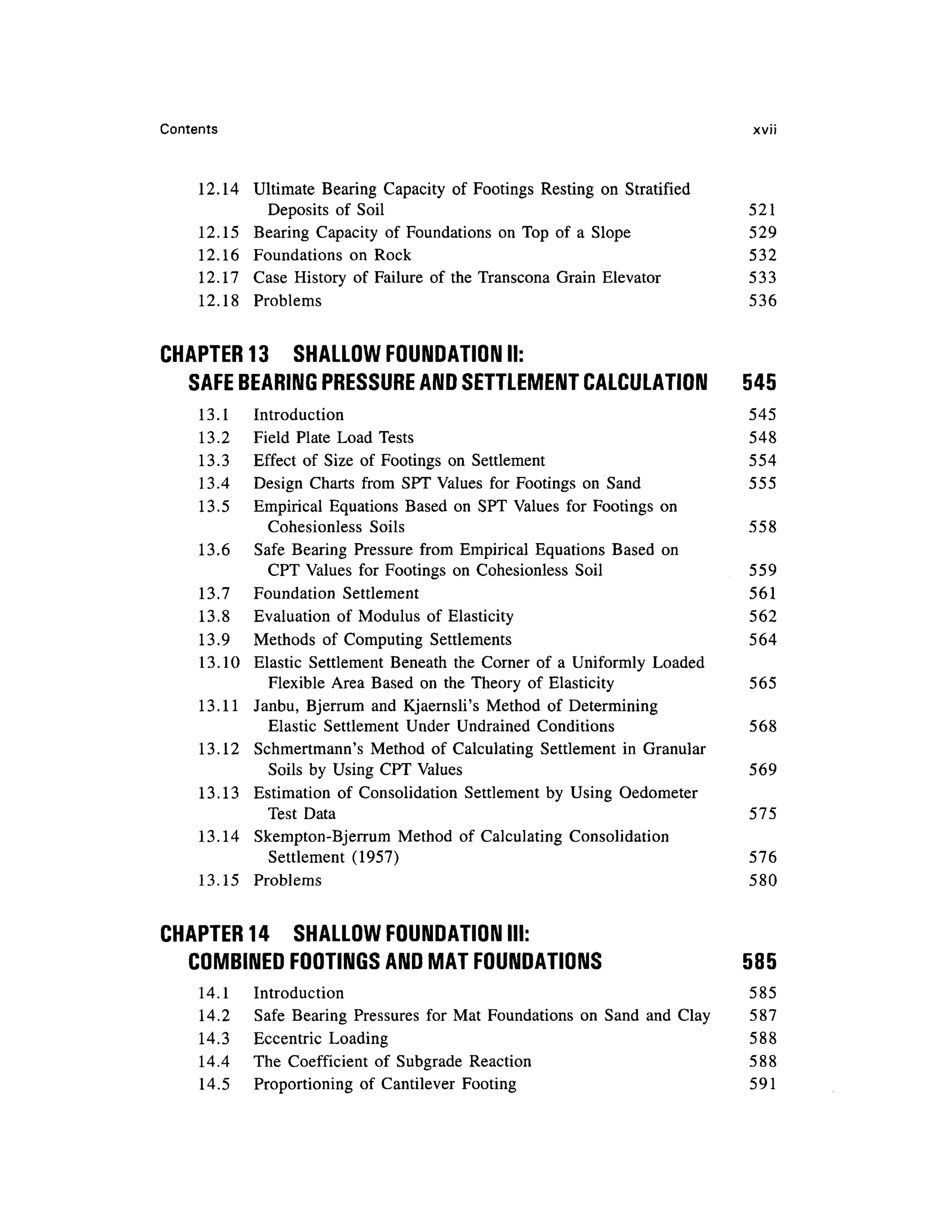

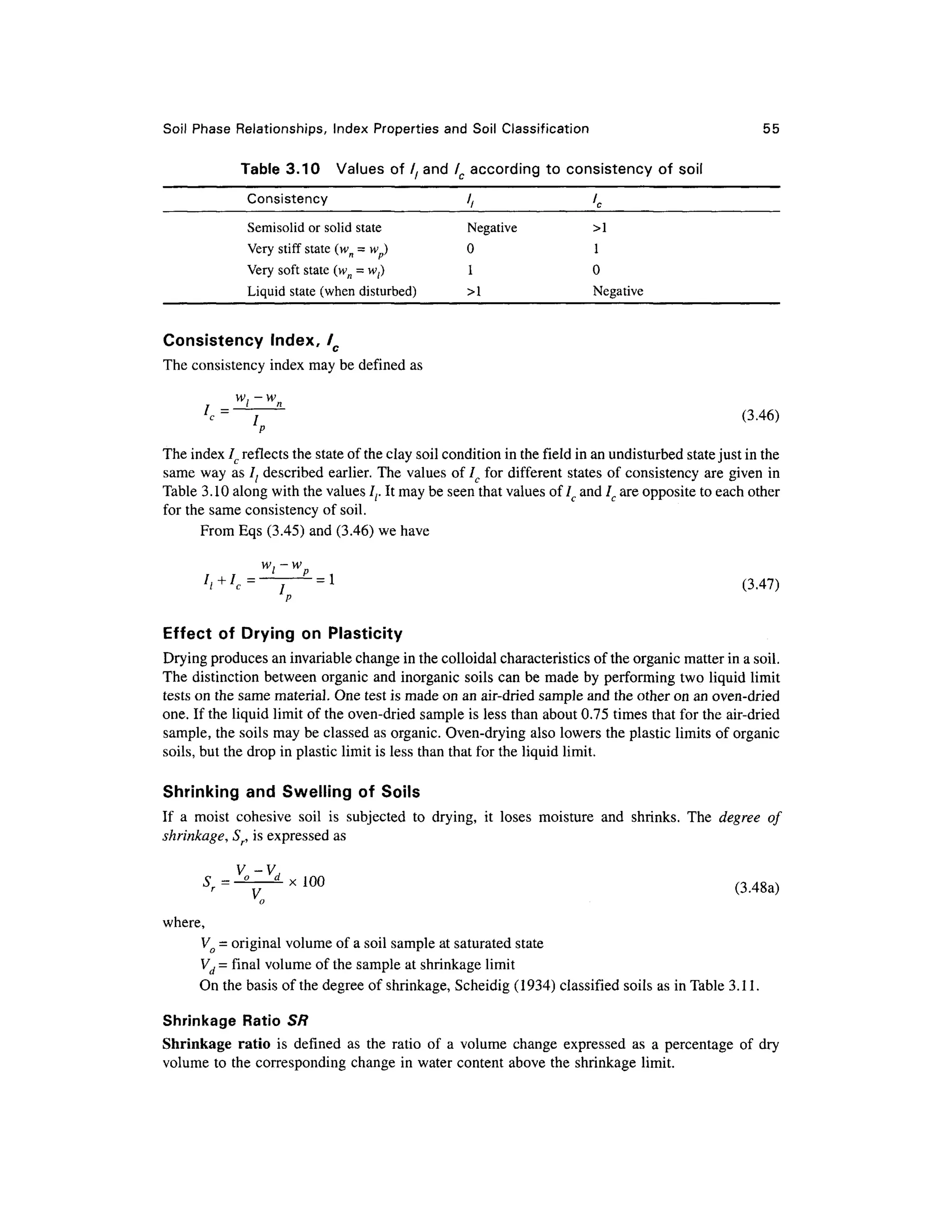

![56 Chapte r 3

Table 3.11 Soi l classificatio n accordin g t o degre e o f shrinkag e S r

Sr% Qualit y o f soi l

< 5 Goo d

5-10 Mediu m goo d

10-15 Poo r

> 1 5 Ver y poor

(V -V,)/V,

SR=' ° d)l d

xlO O (3-48b )

W

0~W

S

where

Vo = initial volume of a saturated soil sample at water content wo

Vd = the final volume of the soil sample at shrinkage limit ws

(wo-ws) = change in the water content

Md = mass of dry volume, Vd, of the sample

Substituting for (wo-ws) i n Eq (3.48b) and simplifying, we have

• ; - • - •

Thus the shrinkage ratio of a soil mass is equal to the mass specific gravity of the soil in its

dry state .

Volumetric Shrinkag e Sv

The volumetric shrinkage or volumetric change is defined as the decrease i n volume of a soil mass,

expressed as. apercentage of the dry volume of the soil mas s whe n the water conten t is reduce d

from the initial wo to the final w s at the shrinkage limit.

d

(3.49)

Linear shrinkage ca n be computed fro m the volumetric change by the following equatio n

1/3

5.. +1.0

LS= l

~ c 1 m Xl

°° percen t

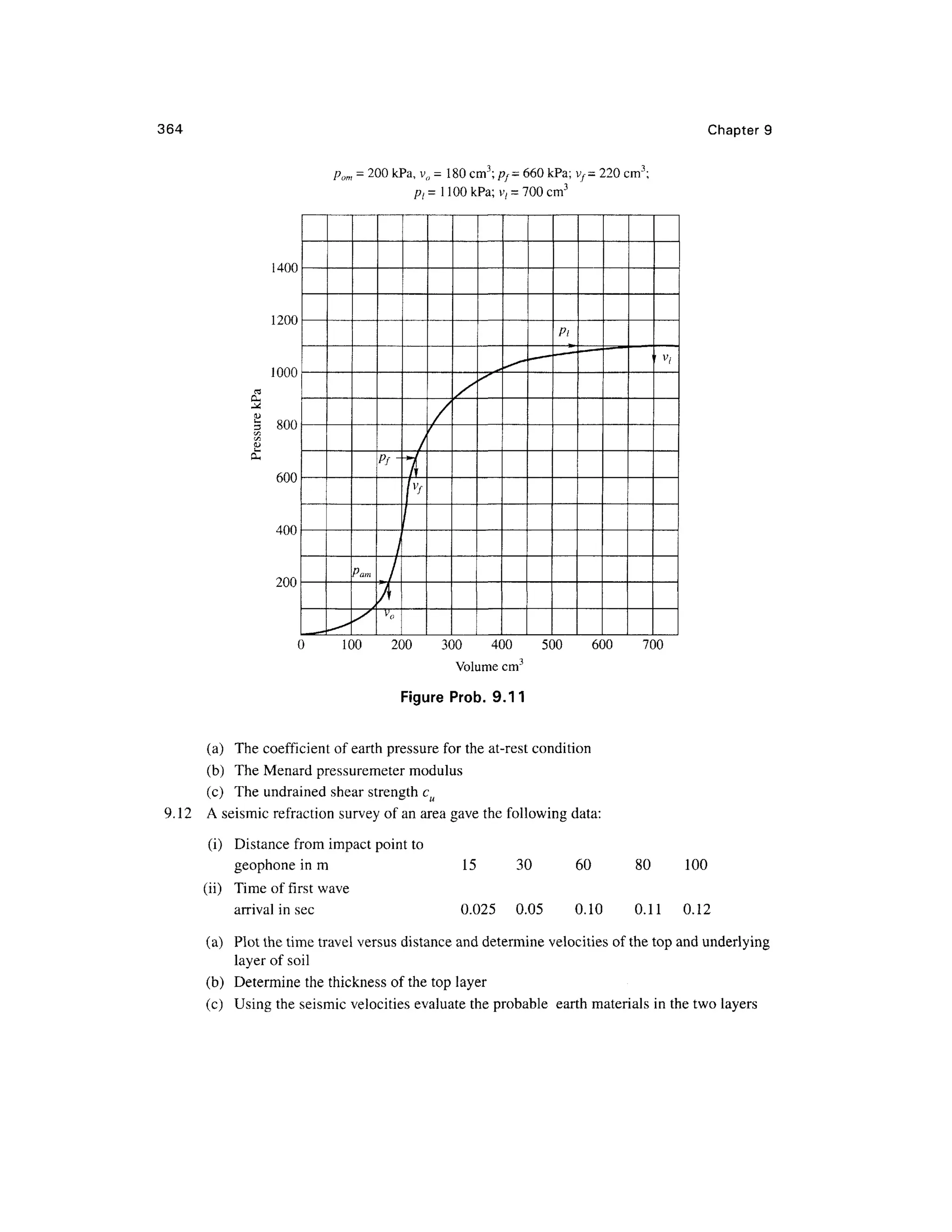

(3-50 )

The volumetri c shrinkag e Sv i s use d a s a decima l quantit y in Eq . (3.50) . Thi s equatio n

assumes that the reduction in volume is both linear and uniform in all directions.

Linear shrinkage can be directly determined by a test [this test has not yet been standardized

in the United States (Bowles, 1992)]. The British Standard BS 1377 used a half-cylinder of mold of

diameter 12. 5 mm and length Lo = 140 mm. The wet sample filled int o the mold is dried and the

final lengt h L,is obtained. Fro m this , the linear shrinkage LS is computed a s](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-75-2048.jpg)

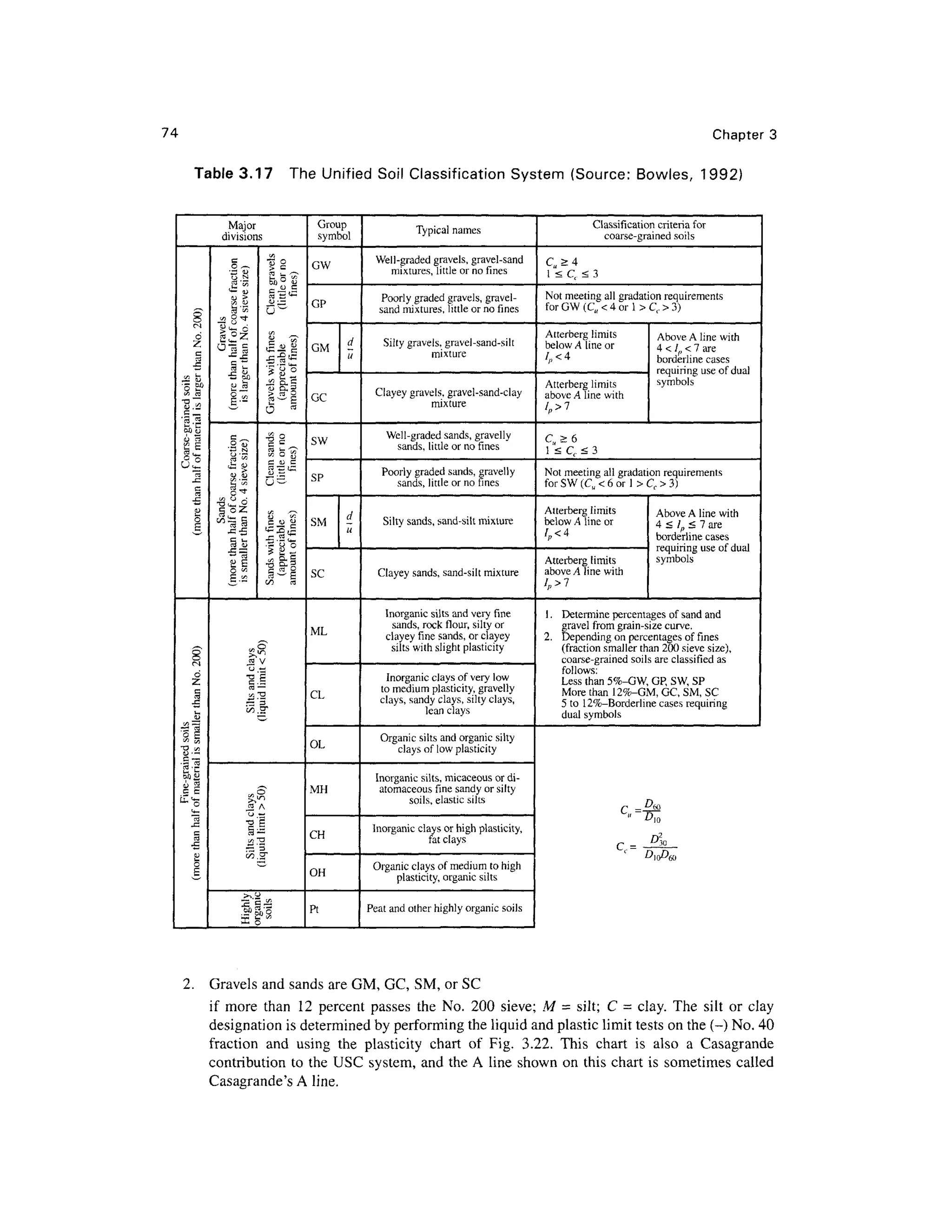

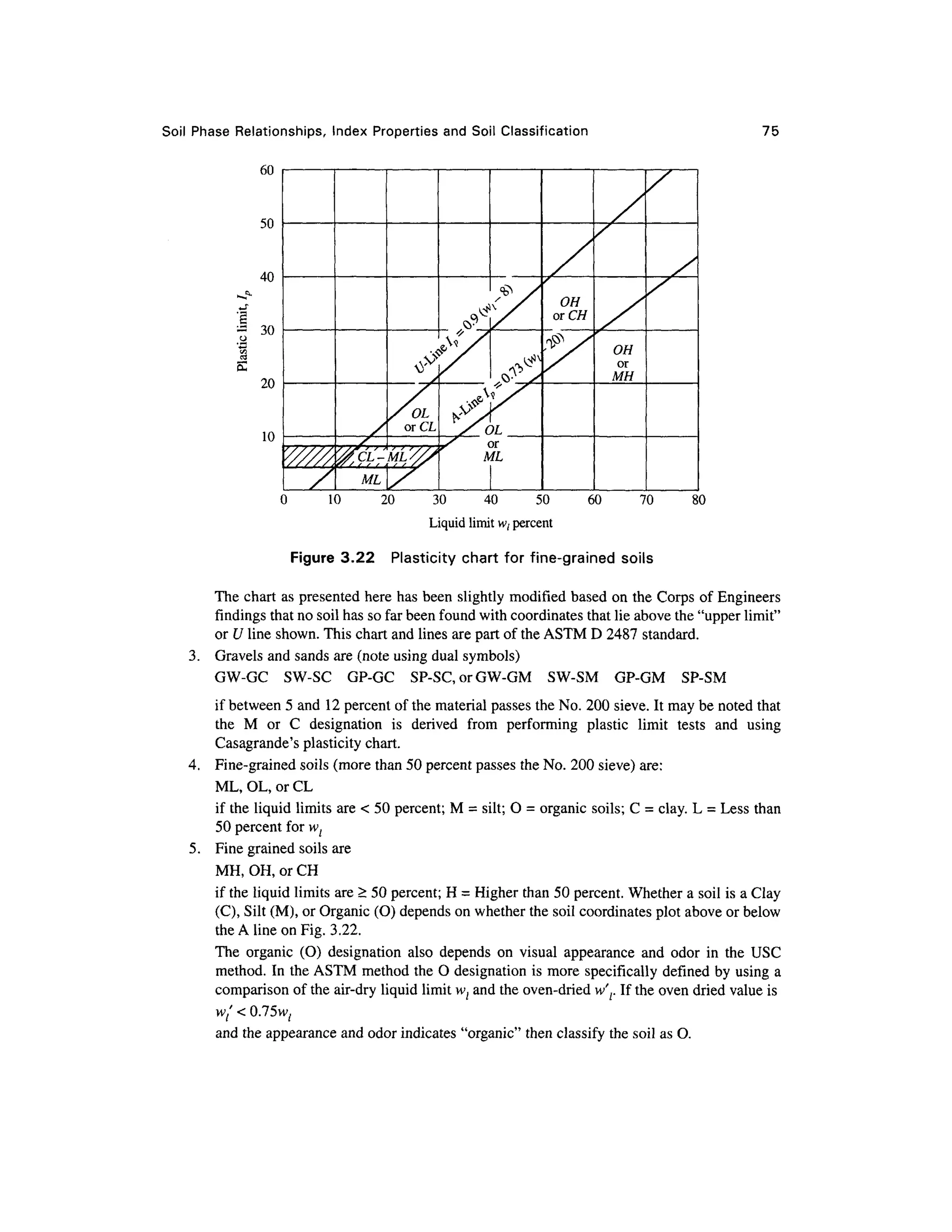

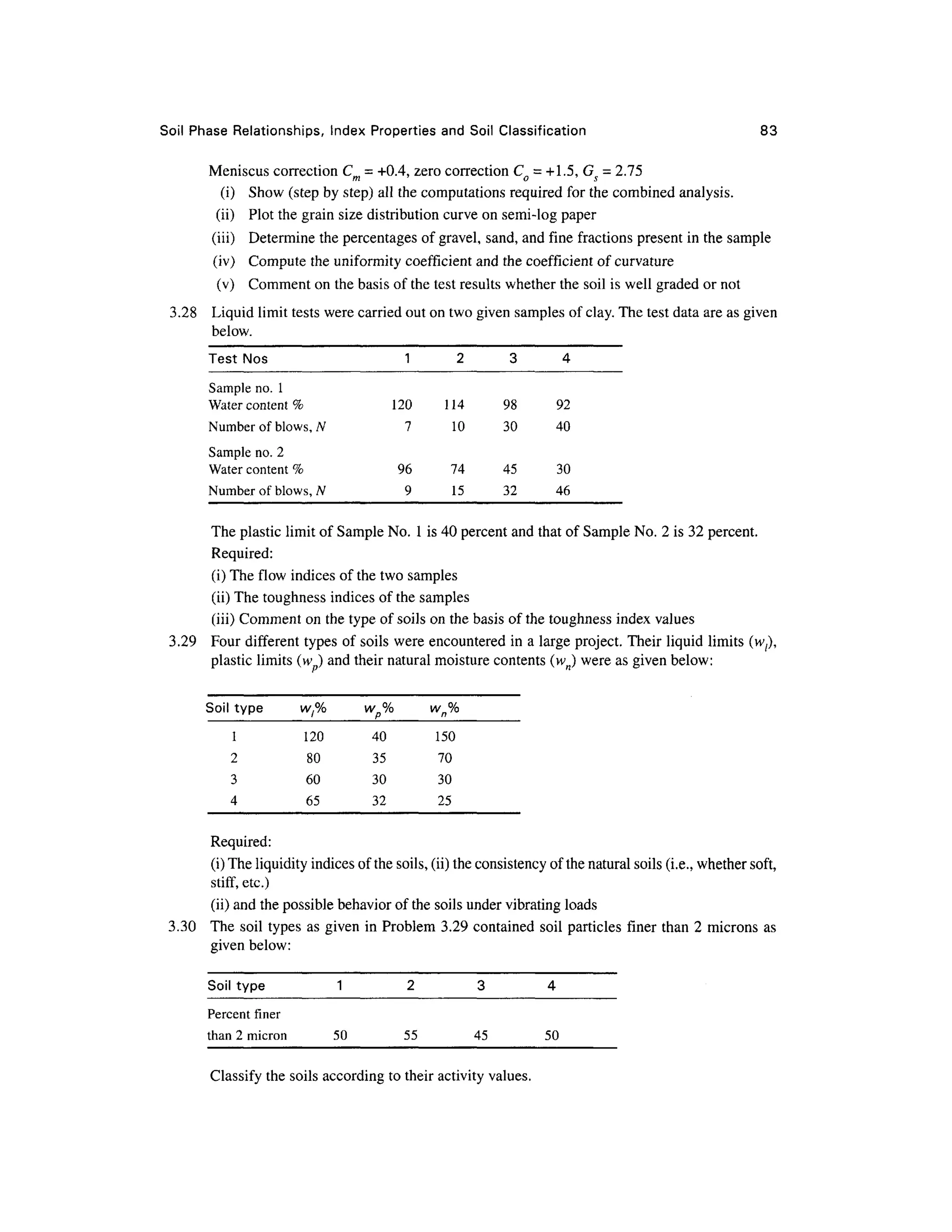

![Soil Phas e Relationships, Inde x Propertie s an d Soil Classificatio n 7 7

Example 3.2 0

A sampl e of inorgani c soi l has the following

grain siz e characteristic s

Size (mm ) Percen t passin g

2.0 (No. 10) 9 5

0.075 (No. 200) 7 5

The liquid limit is 56 percent, and the plasticity index 25 percent. Classify the soil according t o the

AASHTO classification system.

Solution

Percent of fine grained soil = 75

Computation of Group Index [Eq . (3.56a)]:

a = 75 -3 5 =4

0

b = 75 -1 5 =60

c = 56-40 = 16, d=

25-W=

15

Group Index, GI = 0.2 x 40 + 0.005 x 40 x 1 6 +0.01 x 60 x 1 5 =20.2

On the basis of percent of fine-grained soils, liquid limit and plasticity index values, the soil

is either A-7-5 or A-7-6. Since (wl - 30) = 56 -30 =26 > /(25) , the soilclassification isA-7-5(20).

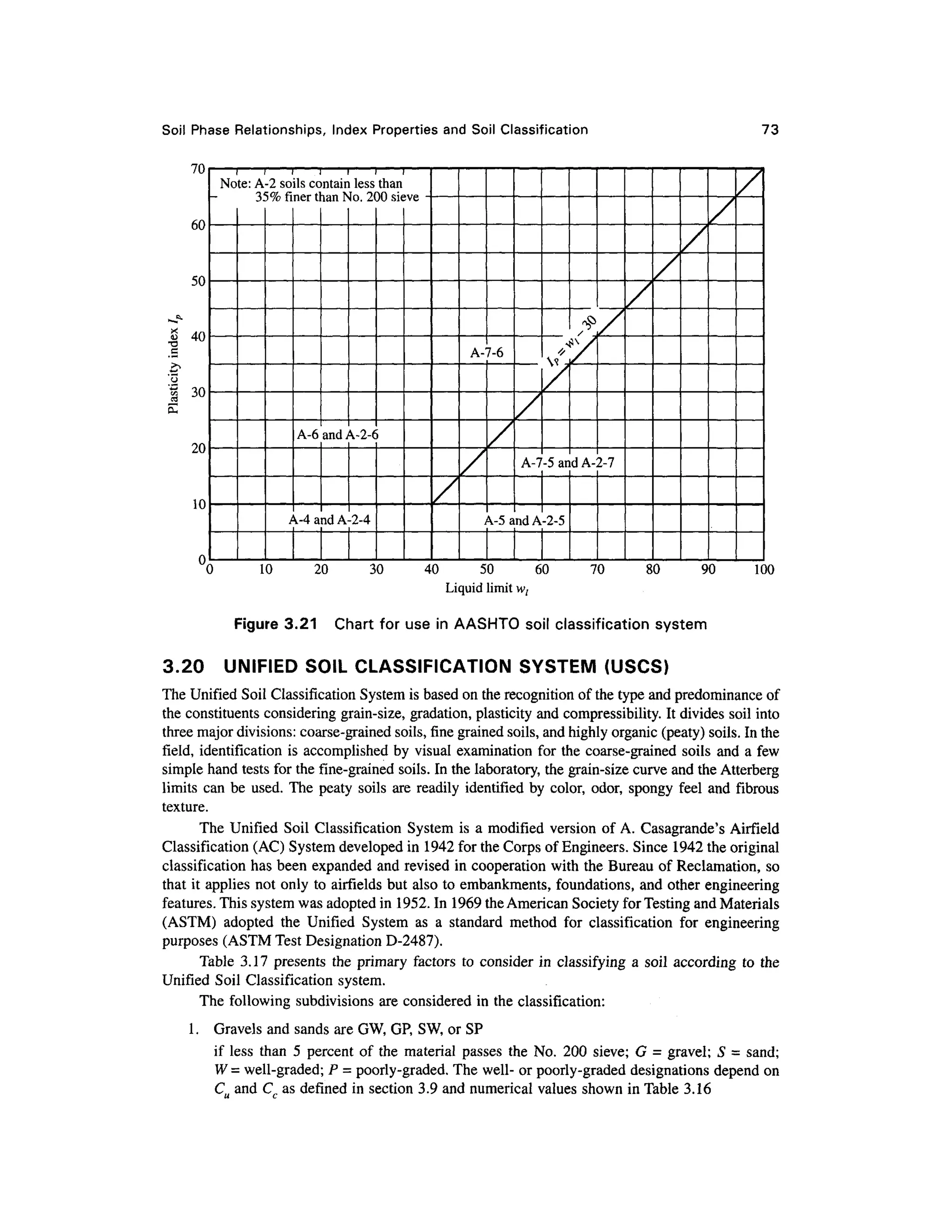

Example 3.2 1

Mechanical analysis on four different samples designated as A, B,C and D were carried out in a soil

laboratory. The results of tests are given below. Hydrometer analysis was carried out on sample D.

The soil is non-plastic.

Sample D: liquid limit = 42, plastic limit = 24, plasticity index =18

Classify the soils per the Unified Soil Classification System.

Samples

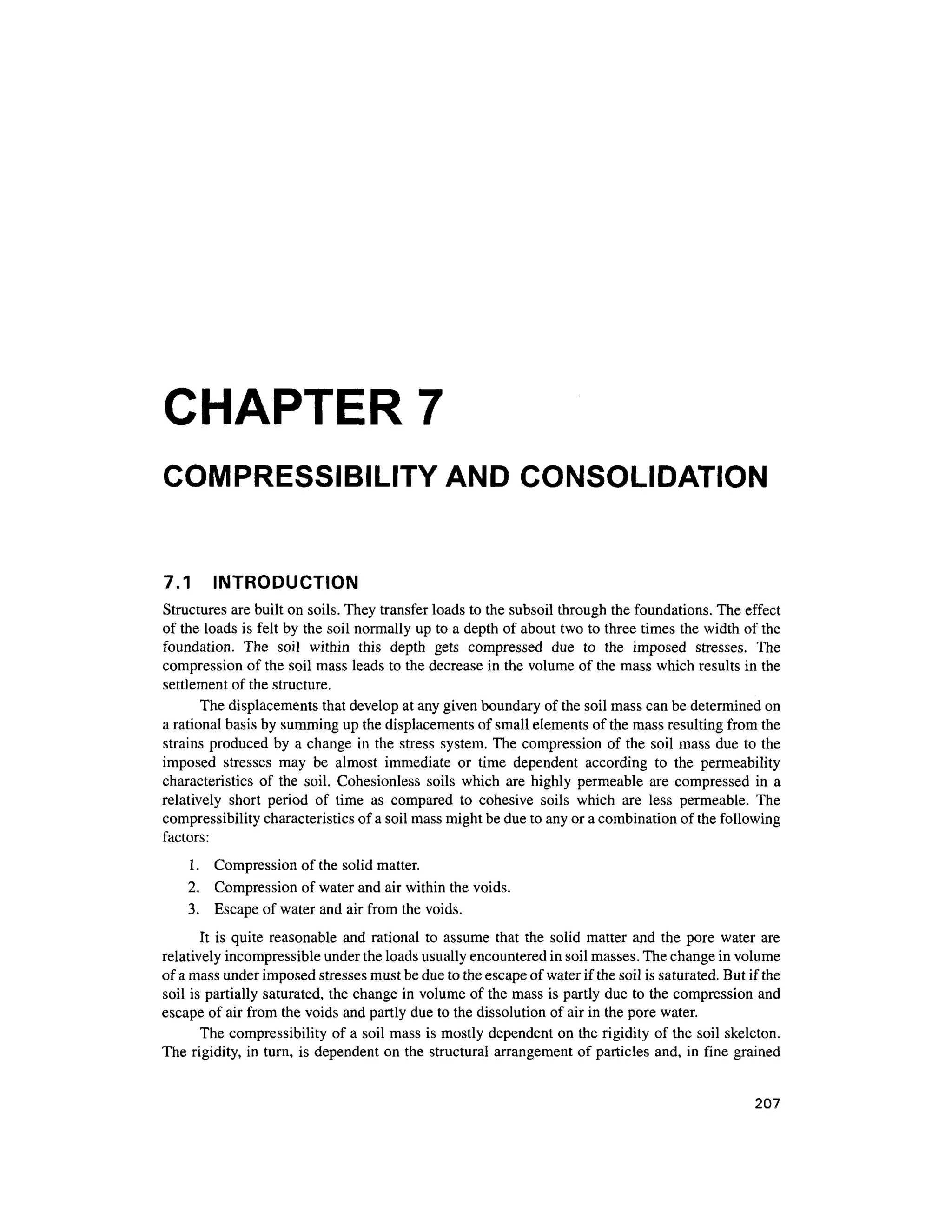

ASTM Sieve

Designation

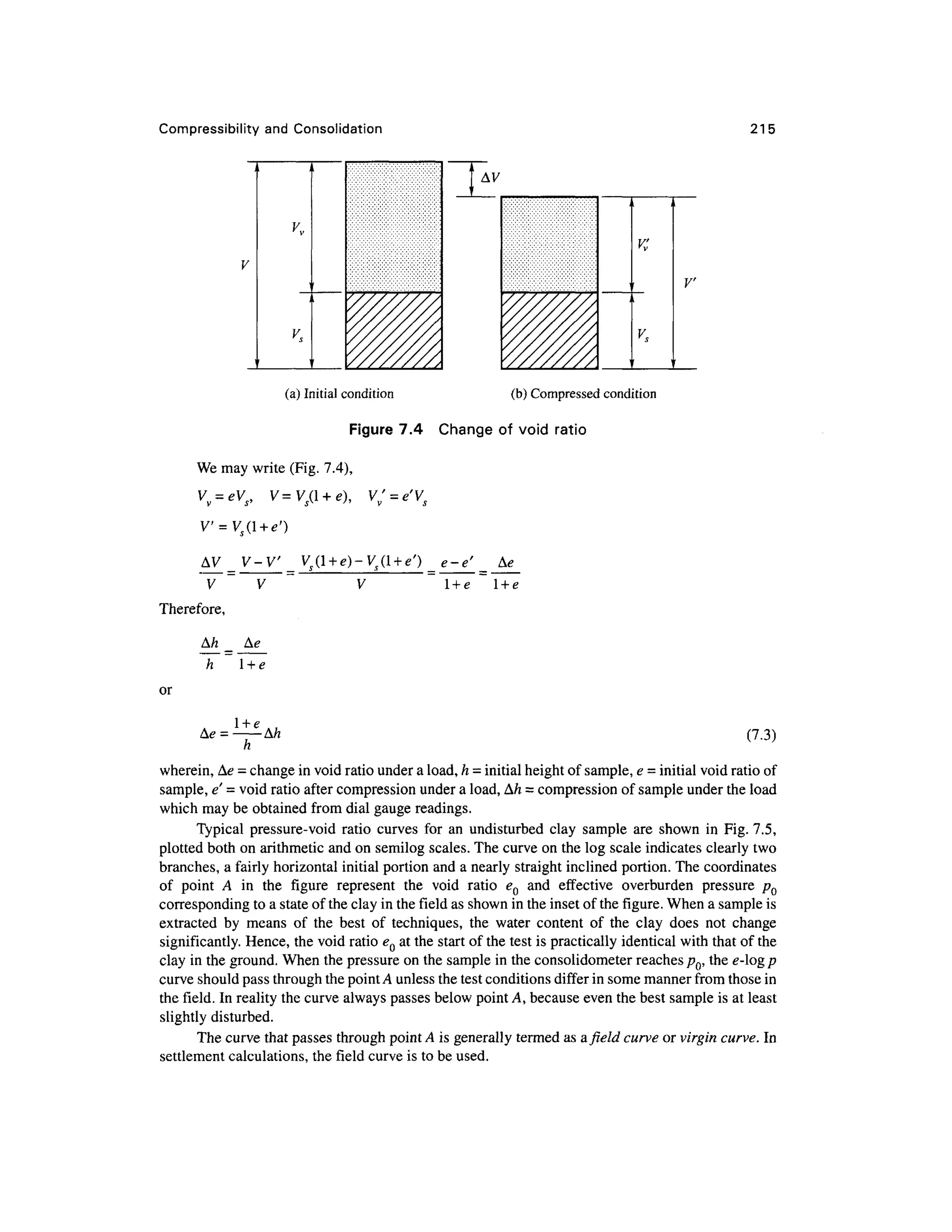

63.0 mm

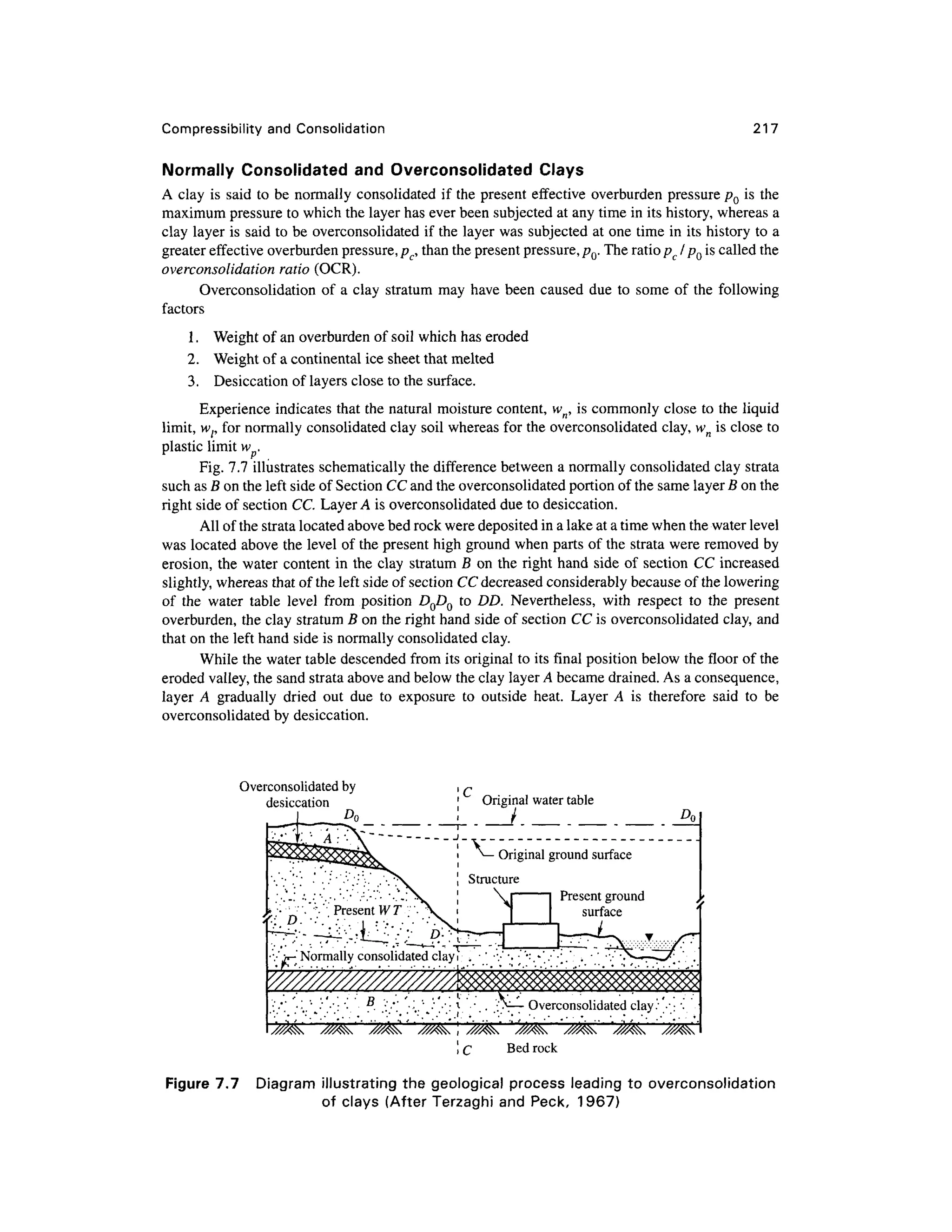

20.0 mm

6.3

2.0mm

600JL I

212 ji

63 ji

20 n

6(1

2 |i

A

Percentage

100

64

39

24

12

5

1

B

finer than

100

98

90

9

2

C

93

76

65

59

54

47

34

23

7

4

D

100

95

69

46

31](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-96-2048.jpg)

![96 Chapte r 4

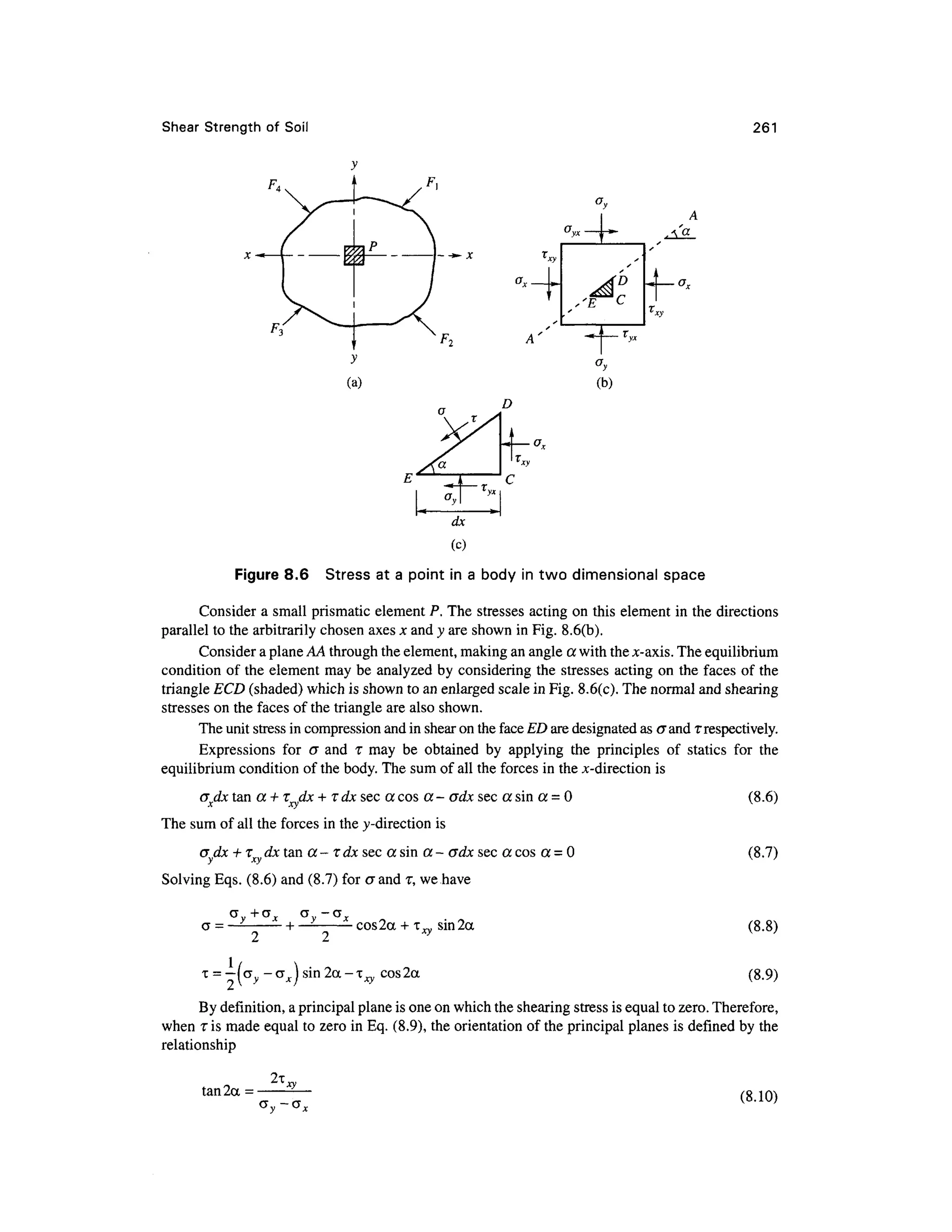

drying, the test specimen weighe d 1. 1 Ib. Assuming Gs = 2.65, calculat e the seepag e velocit y of

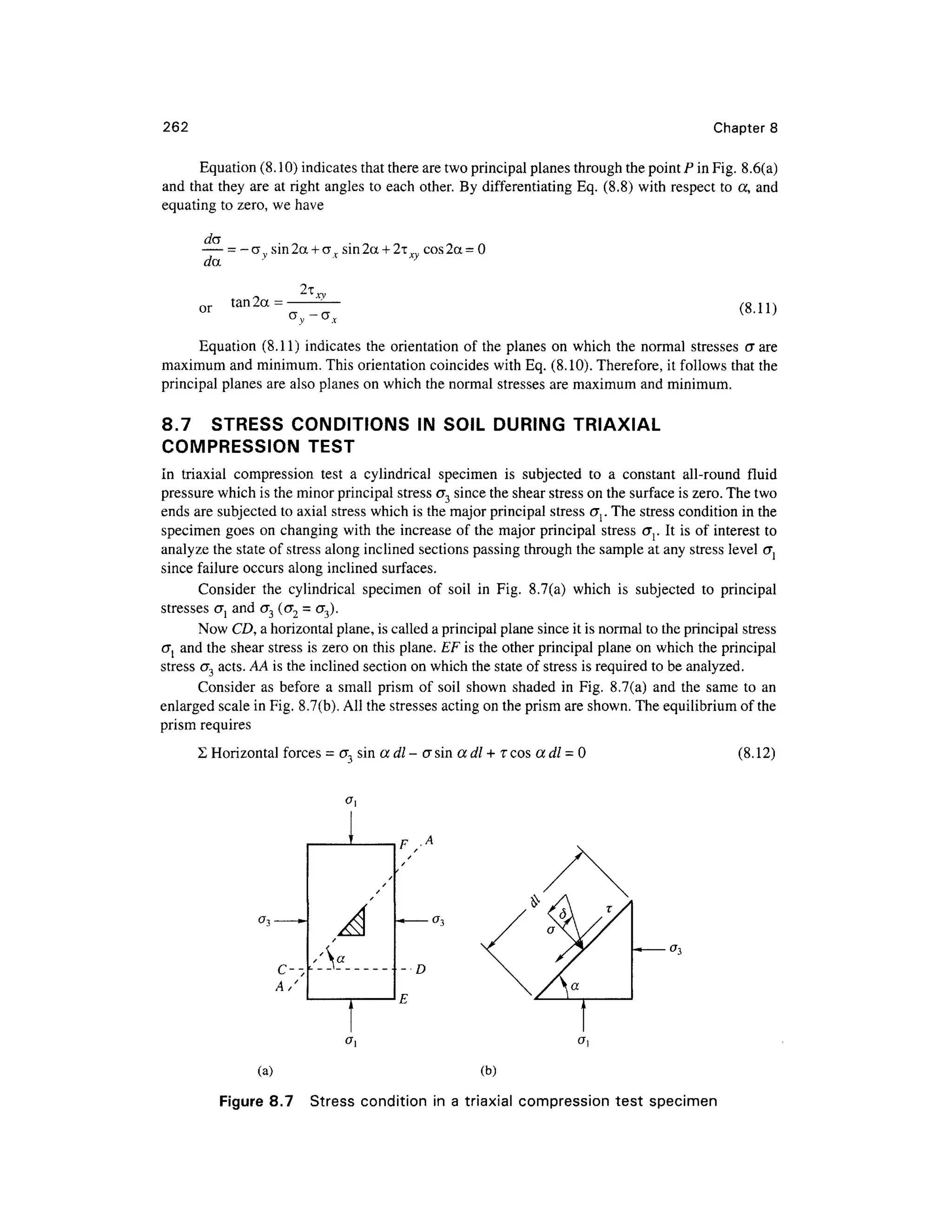

water during the test.

Solution

From Eq. (4.9), k = ^-= -

2633x23

6

-

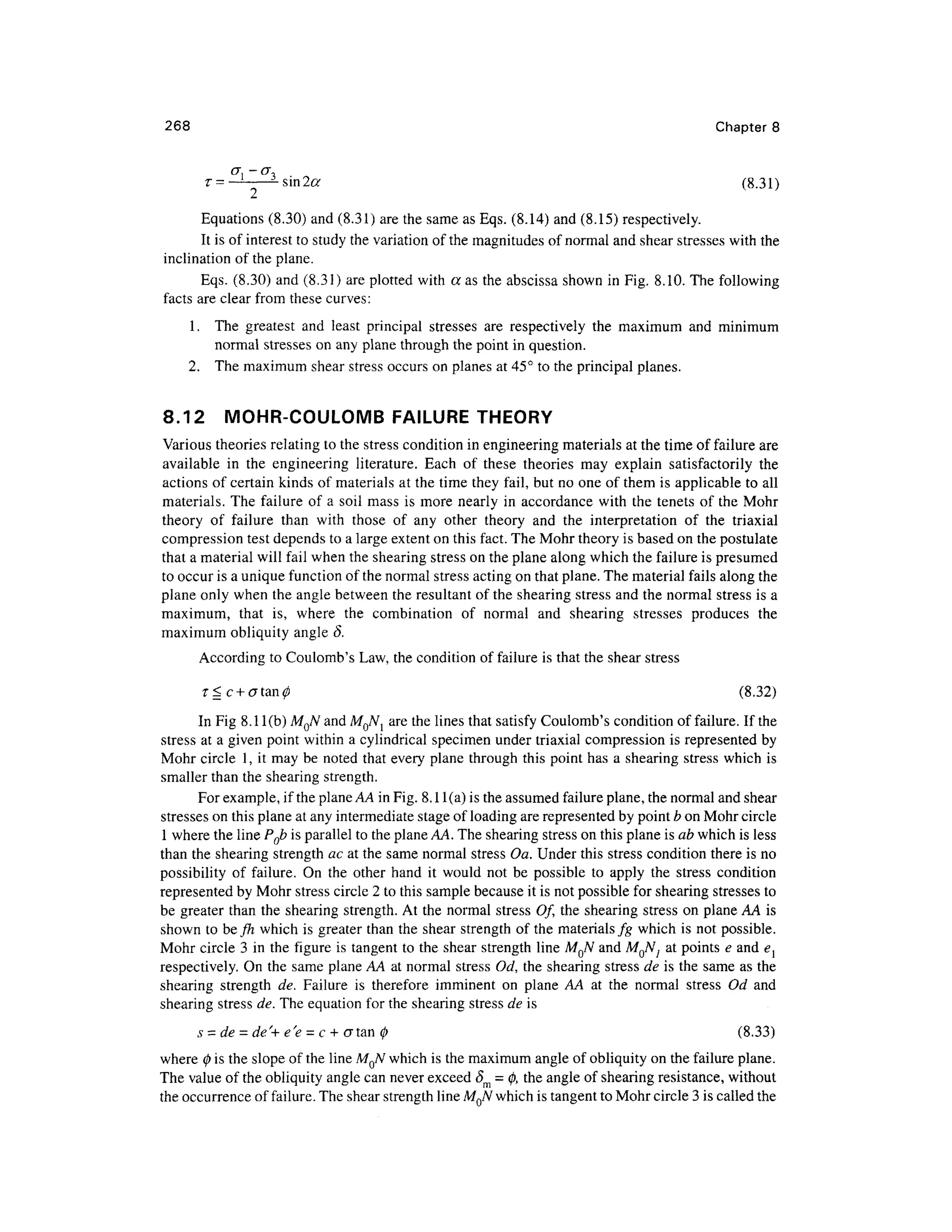

=0.8x 10~3

in./se c

hAt 15.75x7.75x10x6 0

Discharge velocity, v =ki = k— = 0.8xlO~3

x — :

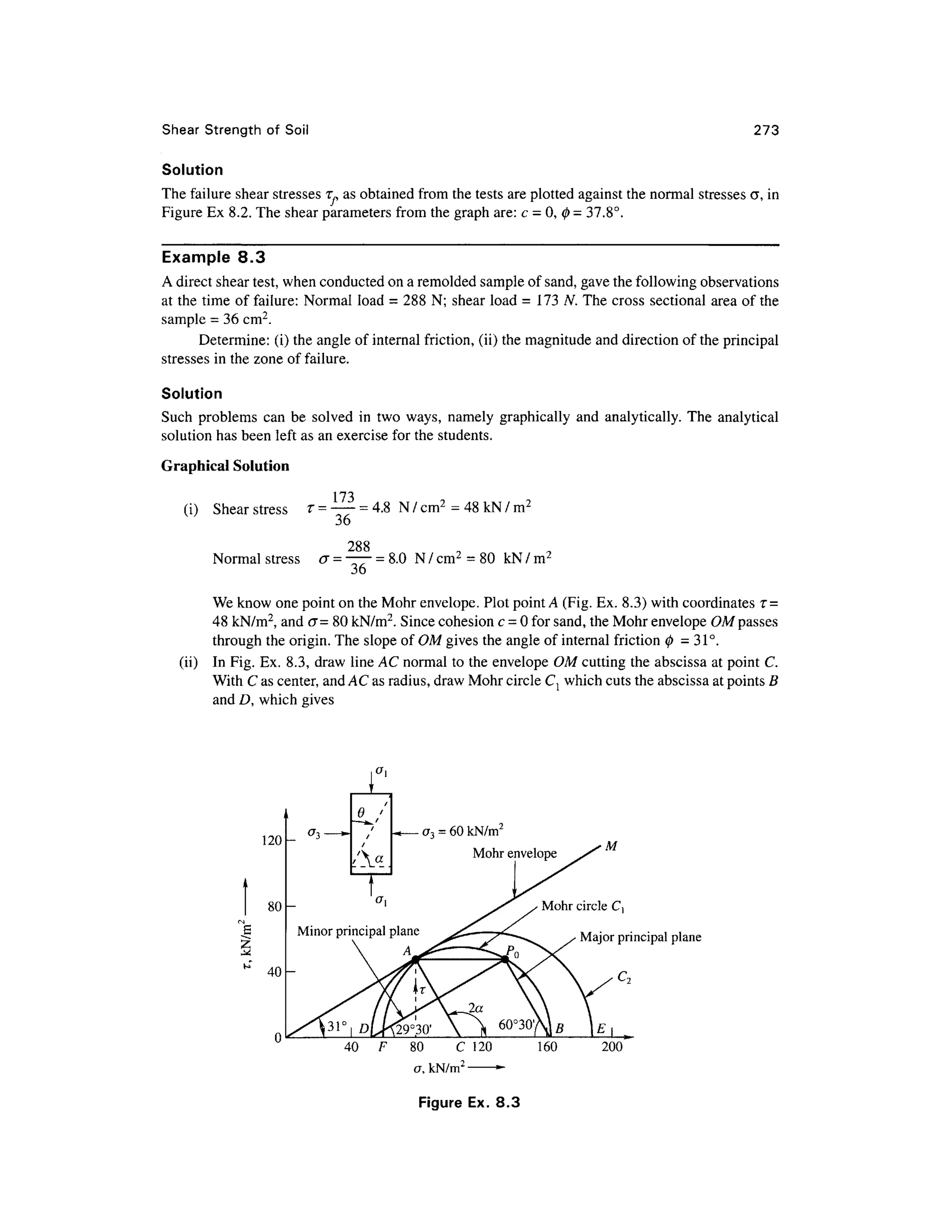

—= 5.34xlO~3

in./sec

L 2.3 6

W 1 1

Y = —s- = -

: -

= 0.0601 lb/in3

=103.9 lb/ft 3

d

V 7.75x2.3 6

Y G

FromEq. (3.18a) , e = ^-^—

Yd

62.4x2.65

or e - -

-- 1 = 0.59 1 5

103.9

°-5915

= 0.37 2

l + e1 + 0.5915

v 5.3 4 xlO~3

Seepage velocity, v =— =

— -

=14.3

5 x10~3

in./sec

6 s

n 0.37 2

Example 4. 4

The hydrauli c conductivity of a soi l sampl e wa s determine d i n a soi l mechanic s laborator y b y

making us e o f a falling hea d permeameter. The dat a used an d th e tes t results obtaine d wer e as

follows: diameter of sample = 2.36 in, height of sample = 5.91 in, diameter of stand pipe = 0.79 in,

initial head h Q = 17.72 in. final hea d hl = 11.81 in. Time elapse d = 1 min 45 sec. Determin e the

hydraulic conductivity i n ft/day .

Solution

The formula for determining k is [Eq. (4.13)]

, . , , .

k = -

log,0 — -

where tis the elapsed time.

A • 3.14x0.79x0.7 9 0 . 1 A 4 ,2

Area of stand pipe, a = -

= 34 x 1

0 4

ft ^

4x12x12

Area of sample, A = 3

-14x2

-36x236

= 304 x 10~4

ft 2

4x12x12

Height of sample, L =(17

-72

~1L81

) = 04925 ft

1 772 118 1

Head, /z n = -^— = 1.477 ft, h, = —

= 0.984 ft

0

1 2 ]

1 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-115-2048.jpg)

![Soil Permeability and Seepag e 101

4.8 BOREHOL E PERMEABILIT Y TEST S

Two types of tests may be carried out in auger hole s for determining k. They are

(a) Fallin g water level method

(b) Risin g water level method

Falling Water Leve l Metho d (case d hol e an d soil flush with bottom )

In thi s test auge r holes ar e made in the field that extend belo w th e water tabl e level . Casing is

provided down to the bottom of the hole (Fig. 4.8(a)). The casing is filled with water which is then

allowed t o see p int o the soil . The rat e o f dro p o f the wate r level i n th e casin g i s observe d b y

measuring the depth of the water surface below the top of the casing at 1, 2 and 5 minutes after the

start of the test and at 5 minutes intervals thereafter. These observations are made until the rate of

drop become s negligibl e o r unti l sufficien t reading s hav e bee n obtained . Th e coefficien t o f

permeability is computed as [Fig. 4.8(a)]

2-3 nrQ H {

k = —log— -

-f,) ff ,

(4.26)

where, H{ = piezometric head ait = tl,H2 = piezometric head at t - t 2-

Rising Wate r Leve l Metho d (case d hol e an d soil flus h with bottom )

This method, most commonly referred to as the time-lag method, consists of bailing the water out

of the casing and observing the rate of rise of the water level in the casing at intervals until the rise

in water level becomes negligible. The rate is observed by measuring the elapsed time and the depth

of the water surface below the top of the casing. The intervals at which the readings are required

will vary somewhat with the permeability of the soil. Eq. (4.26) is applicable fo r this case, [Fig

.

4.8(b)]. A rising water level test should always be followed by sounding the bottom of the holes to

determine whether the test created a quick condition.

HI a t t =

H a t t = t

(a) Falling water head method (b ) Rising water head method

Figure 4.8 Fallin g and rising water method of determining k](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-120-2048.jpg)

![Soil Permeabilit y an d Seepage 105

Sand

Fine Medium] Coars e

Sand

10"

T3

8 io -

-3

2

•o

X

10-

10'

C, ,=1 - 3

10- 10- 10° IO1

D5 (mm)

Figure 4.11 Influenc e o f gradation o n permeability o n granular soil s

(after Kenne y et al., 1984 )

where k = a soil constant depending on temperature and void ratio e .

F(e) ma y be expressed as

F(e) =

o

2e

l + e

(4.32)

When e = 1, F(e) ~ 1 . Therefore k represent s th e hydraulic conductivity corresponding t o void

ratio e -1 . Since k i s assumed a s a constant, k is a function of e only.

By substituting in F(e), the limiting values,;c = 0, x = 0.25, and x = 0.5, we get

ForJ c = 0,

x = 0.25,

(4.33)

(4.34)

x = 0.50

F,(e) represents the geometric mean of F.(e) and F.(

The arithmetic mean of the functions F^e) an d F3(e) is

(4.35)

= e2

(4.36)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-124-2048.jpg)

![Soil Permeabilit y an d Seepage 107

3.5

3.0

2.5

•|2.0

1.0

0.5

0

Clay

O Batiscon

A Berthierville

D St . Hilaire

V Vosb y

• Bosto n blue

10- 10" 10,-8

Figure 4.14 Result s of falling-head and constant-head permeabilit y test s on

undisturbed samples of sof t clay s (Terzaghi, Pec k and Mesri, 1996 )

Fine Graine d Soil s

Laboratory experiment s hav e shown that hydraulic conductivity of very fin e graine d soil s are not

strictly a function o f void ratio since there is a rapid decrease i n the value of k for clays below the

plastic limit. This is mostly due to the much higher viscosity of water in the normal channels which

results from the fact that a considerable portion of water is exposed t o large molecular attractions by

the closely adjacent solid matter. It also depends upon the fabric of clays especially thos e of marine

origin whic h ar e often flocculated. Fig . 4.13 shows that the hydraulic conductivity in the vertica l

direction, at in situ void ratio eQ, is correlated wit h clay fraction (CF) finer than 0.002 mm an d with

the activity A (= I p/CF).

Consolidation o f soft clays may involve a significant decrease i n void ratio and therefore of

permeability. The relationships between e and k (log-scale) fo r a number of soft clays are shown in

Fig. 4.14 (Terzaghi, Peck, an d Mesri 1996) .

Example 4. 5

A pumping test was carried ou t for determining the hydraulic conductivity of soil in place. A well

of diamete r 40 cm wa s drilled dow n t o an impermeable stratum . The depth o f wate r abov e th e

bearing stratum was 8 m. The yield from th e well was 4 mVmin at a steady drawdow n of 4.5 m.

Determine th e hydraulic conductivity of the soil in m/day if the observed radiu s of influence was

150m.

Solution

The formula for determining k is [Eq. (4.18)]

k =

2.3 q

xD0(2H-D0) r 0

q = 4 m3

/min = 4 x 60 x 24 m3

/day

D0 = 4.5 m, H = 8 m, R . = 150 m, r Q = 0.2 m](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-126-2048.jpg)

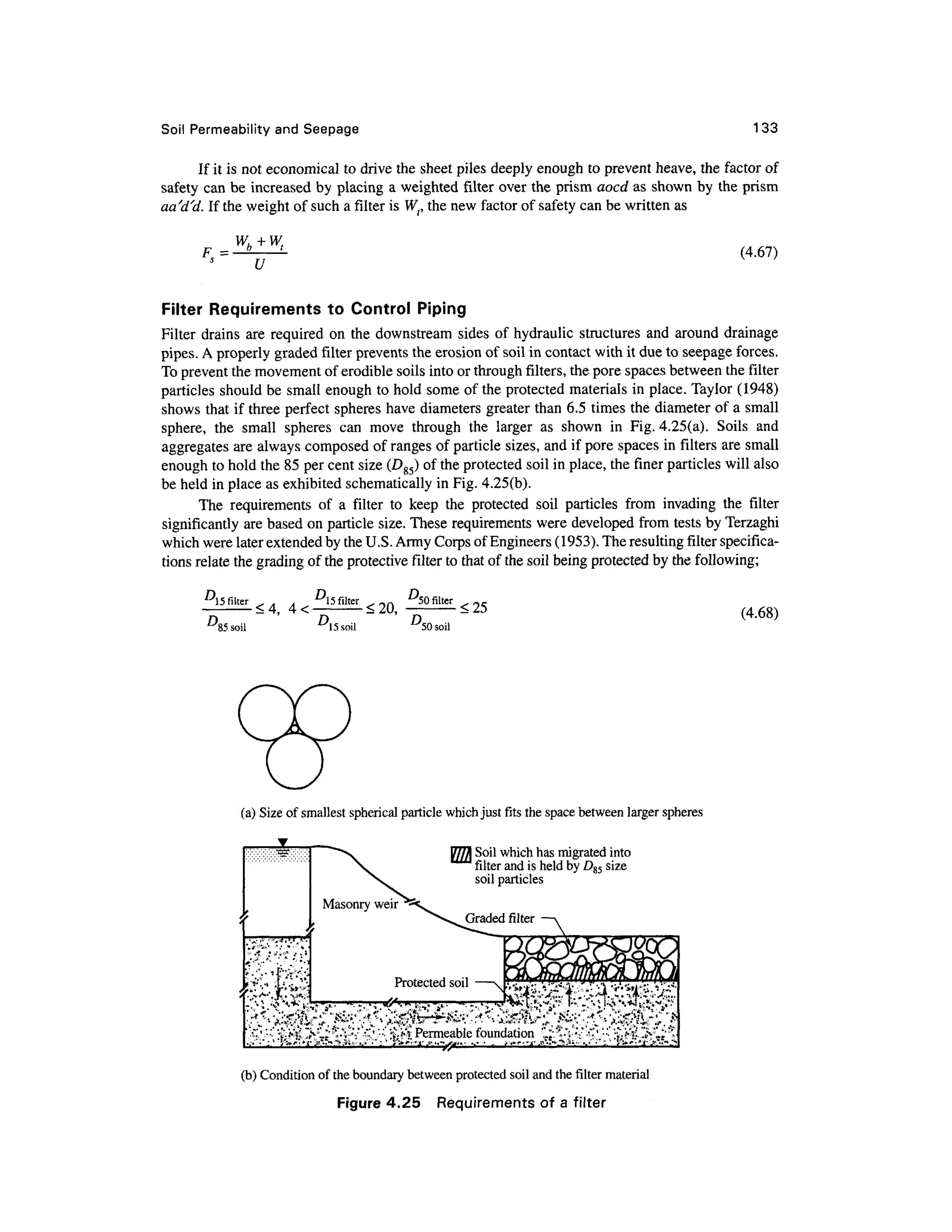

![134 Chapter 4

10 1.0

Grain size D mm

0.1

= 0.015 mm

0.01

Figure 4.26 Grai n size distribution curves for grade d filter and protected material s

The criteria ma y be explained as follows:

1. Th e 1 5 per cent size (D15) o f filter material must be less than 4 times the 85 per cent size

(D85) of a protected soil. The ratio of D15 of a filter to D85 of a soil is called the piping ratio.

2. Th e 1 5 per cent size (D15) o f a filter material should be at least 4 times the 1 5 per cent size

(D]5) of a protected soi l but not more than 20 times of the latter.

3. Th e 50 per cent size (D5Q) o f filter material should be less than 25 times the 50 per cent size

(D50) of protected soil .

Experience indicate s that if the basic filter criteria mentioned above are satisfied in every part

of a filter, piping cannot occur under even extremely sever e conditions.

A typica l grai n siz e distributio n curve o f a protected soi l an d th e limitin g sizes o f filte r

materials fo r constructing a graded filter is given in Fig. 4.26. The size of filter materials must fall

within the two curves C2 and C3 to satisfy th e requirements.

Example 4.1 6

Fig. Ex. 4.1 6 give s th e sectio n o f a homogeneou s da m wit h a hydrauli c conductivit y

k = 7.87 4 x 10"5

in/sec. Draw the phreatic line and compute the seepage loss per foot length of the

dam.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-153-2048.jpg)

![136 Chapte r 4

-^--035

a + Aa

or Aa = 0.35 (a + Aa) = 0.35 x 24.6 = 8.61 ft

From Eq . (4.60)

q = kyQ

where k = 7.874 x 10~ 5

in/sec or 6.56 x 10" 6

ft/sec an d yQ = 7.413 f t

q = 6.56 x 10-6

x 7.413 = 48.63 x 10" 6

ft3

/sec per ft length of dam.

Example 4.1 7

An earth dam which is anisotropic is given in Fig. Ex. 4.17(a). The hydraulic conductivities kx and

kz i n th e horizonta l an d vertica l direction s ar e respectivel y 4. 5 x 10~ 8

m/ s an d 1. 6 x 10~ 8

m/s .

Construct th e flo w ne t and determine th e quantity of seepage through the dam. What i s the por e

pressure a t point PI

Solution

The transforme d sectio n i s obtained b y multiplyin g the horizonta l distances b y ^Jk z I kx an d b y

keeping the vertical dimensions unaltered. Fig. Ex. 4.17(a) is a natural section of the dam. The scale

factor for transformation i n the horizontal direction i s

Scale factor = P - = JL6xl

°"8

B = 0.6

]kx V4.5X10- 8

The transforme d sectio n o f the da m i s given i n Fig. Ex. 4.17(b) . The isotropi c equivalen t

coefficient o f permeability is

k =

e

Confocal parabolas can be constructed with the focus of the parabola a t A. The basic parabol a

passes throug h point G such that

GC=0.3 H C = 0.3x2 7 = 8.10m

The coordinates of G are:

x = +40.80 m, z = +18.0 m

7 2

- 4 f l 2

As per Eq. (4.58) x = 9 . (a )

Substituting for x and z, we get, 40.8 0 =

Simplifying we have, 4a 2

+ 163.2aQ -32

4 =0

Solving, aQ = 1.9 m

Substituting for aQ in Eq. (a) above, we can write](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-155-2048.jpg)

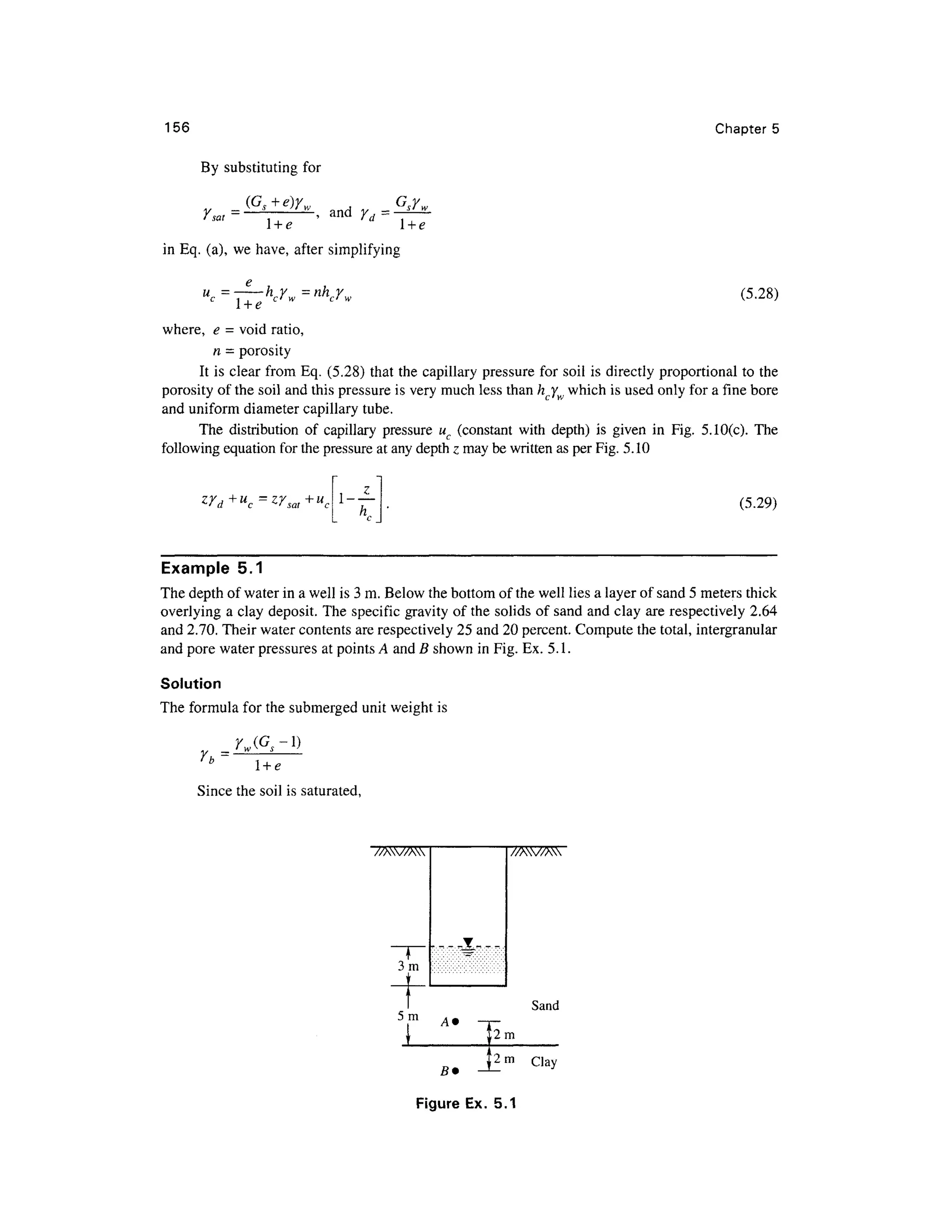

![Stress Distributio n in Soils du e to Surfac e Loads 175

that I B ha s a maximu m valu e o f 0.4 8 a t r/ z = 0, i.e. , indicatin g thereb y tha t th e stres s i s a

maximum below th e point load .

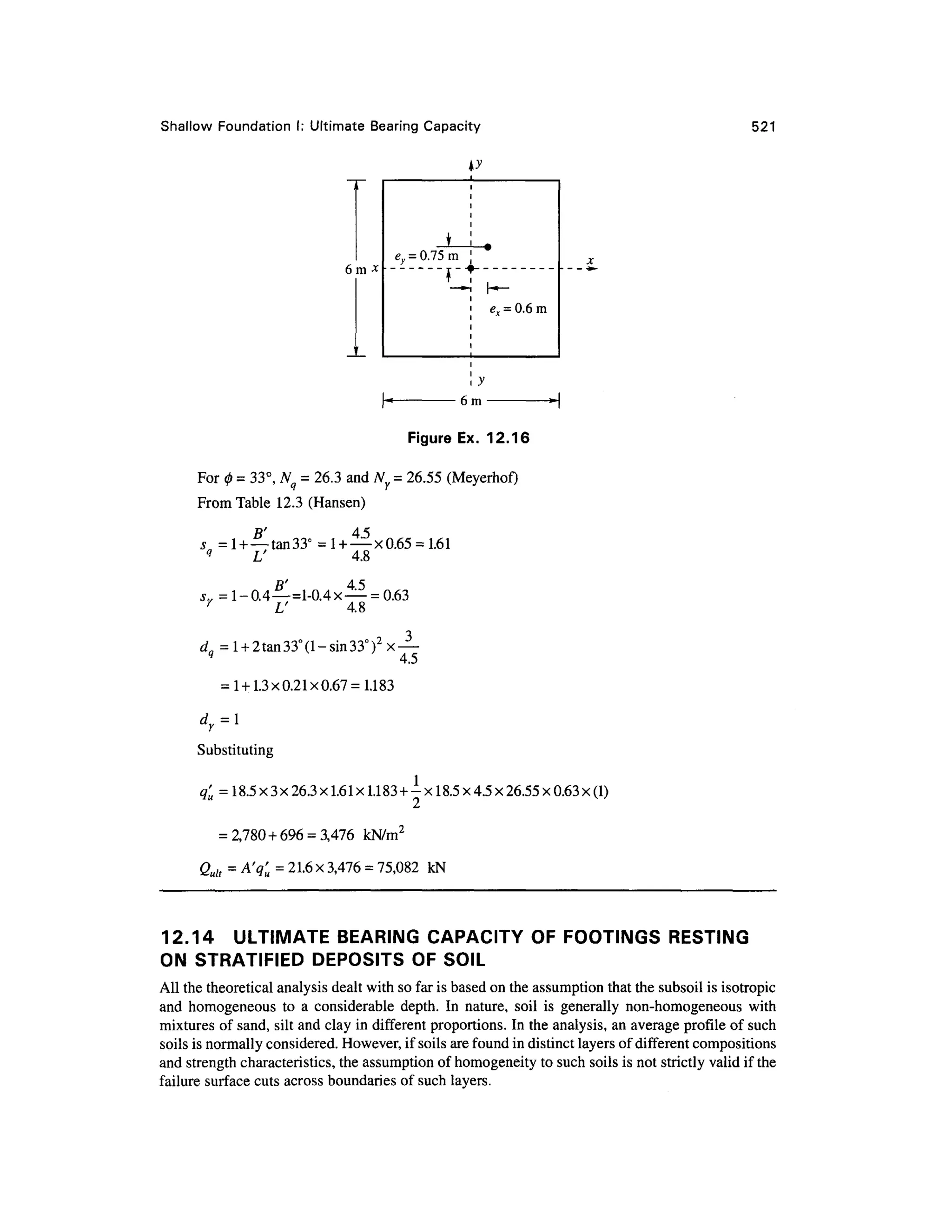

6.3 WESTERGAARD' S FORMUL A FO R POINT LOAD S

Boussinesq assume d tha t the soil is elastic, isotropic an d homogeneous for the development o f a

point loa d formula . However, th e soil i s neither isotropic no r homogeneous. Th e mos t commo n

type of soils that are met in nature are the water deposited sedimentary soils. When the soil particles

are deposited i n water, typical clay strata usually have their lenses of coarser materials within them.

The soil s o f thi s typ e ca n b e assume d a s laterall y reinforce d b y numerous , closel y spaced ,

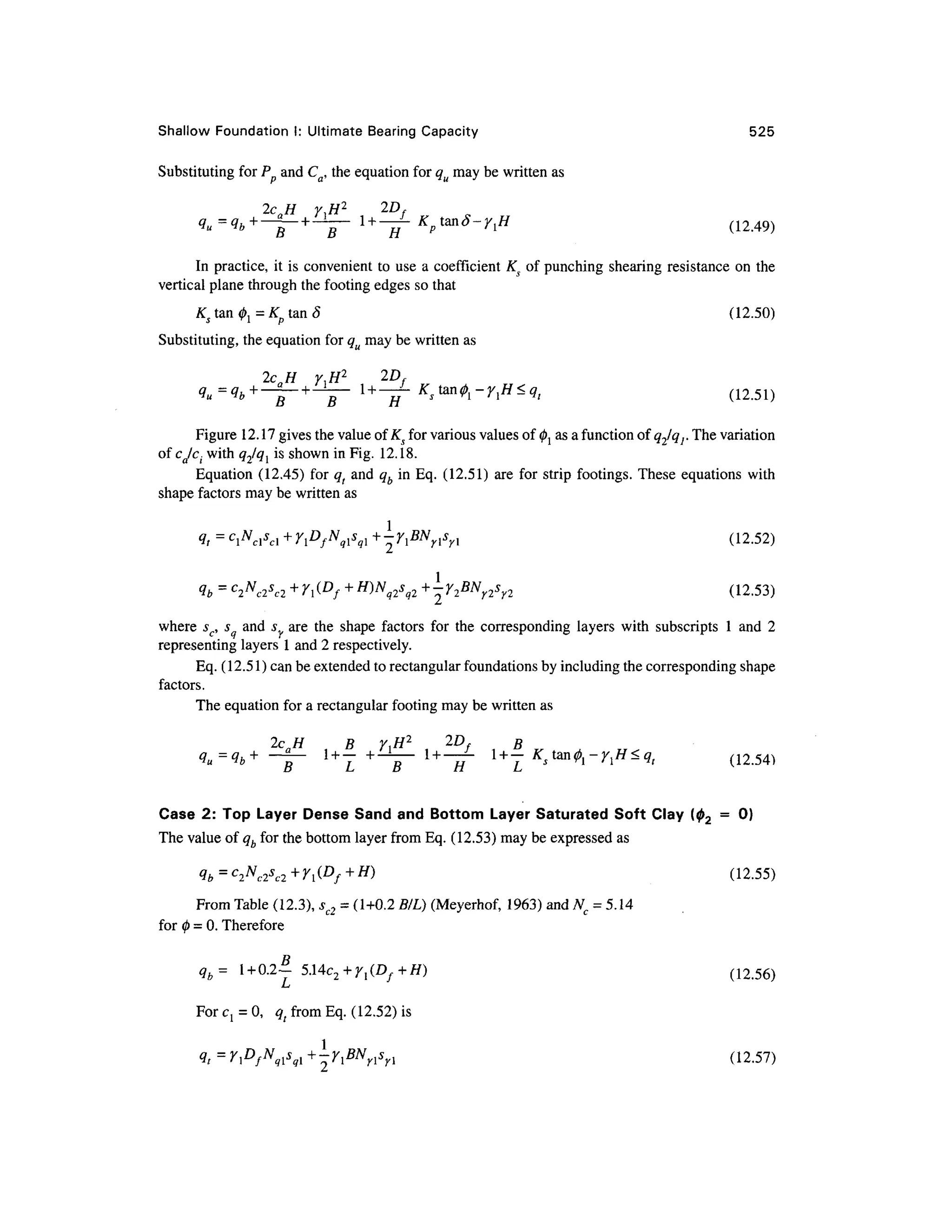

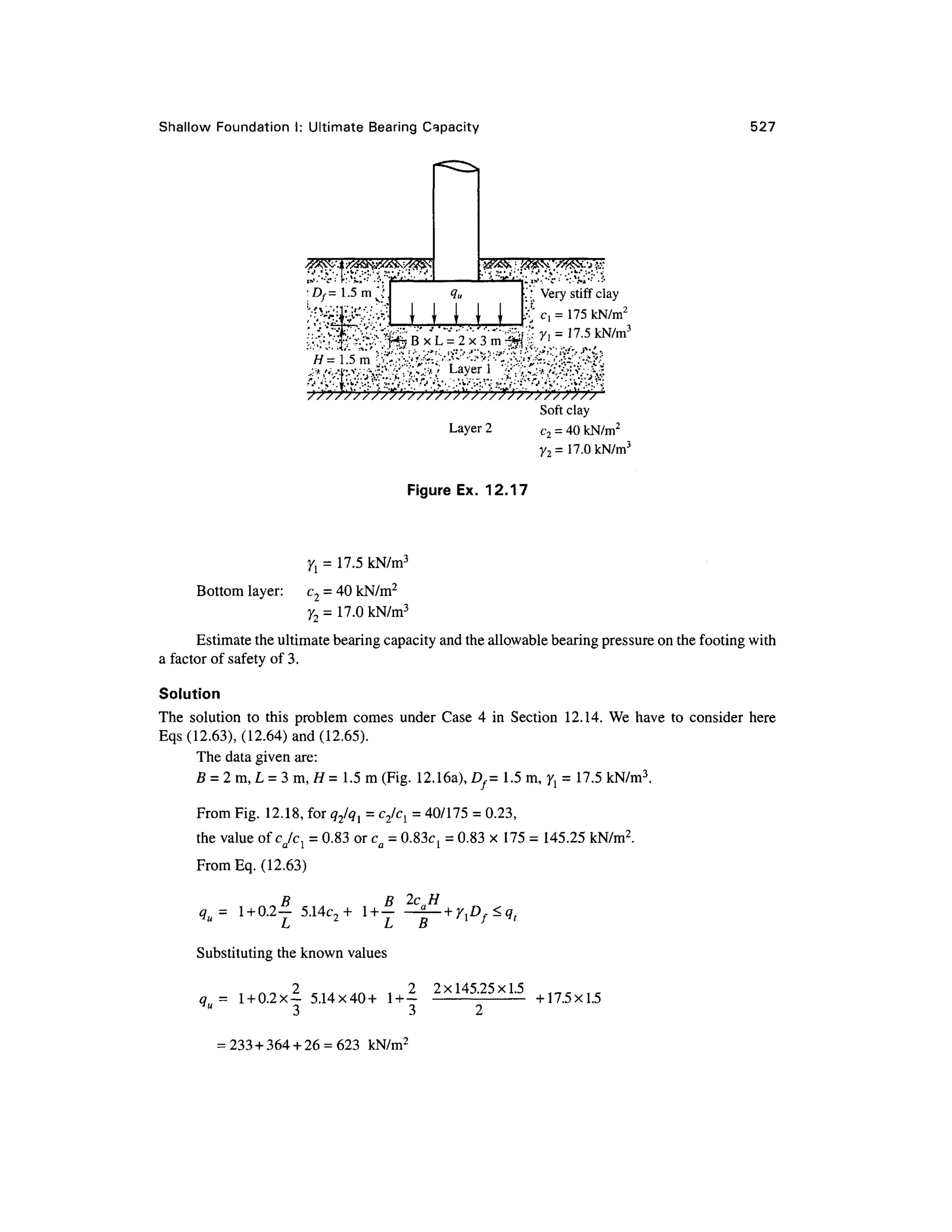

horizontal sheets of negligible thickness but of infinite rigidity, which prevent the mass as a whole

from undergoing lateral movement of soil grains. Westergaard, a British Scientist, proposed (1938 )

a formula for the computation of vertical stress oz b y a point load, Q, at the surface as

cr, -'

Q

,3/2 2 M (6.2)

in whichfj, i s Poisson's ratio. Iffj, i s taken as zero for all practical purposes, Eq . (6.2) simplifies t o

Q 1 Q

[l +2(r/z)2

]3

'2 (6.3)

where /,, , =

(II a)

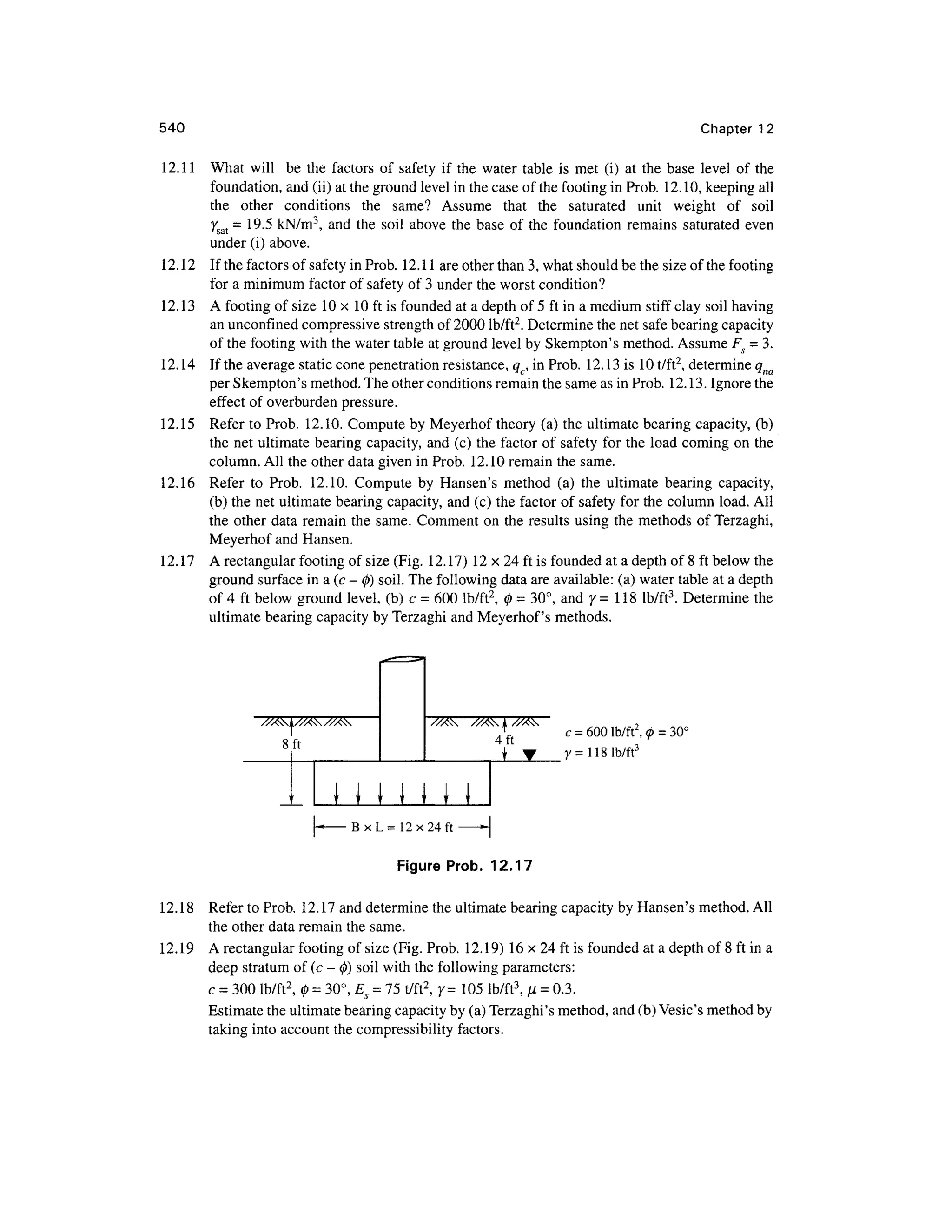

[l + 2(r/z)2

]3/2

is the Westergaard stres s coefficient . Th e variatio n o f / wit h the

ratios of (r/z) i s shown graphically in Fig. 6.2 along with the Boussinesq's coefficien t IB. The value

of Iw a t r/z = 0 is 0.32 which is less than that of IB by 33 per cent.

h or 7

w

0 0. 1 0. 2 0. 3 0. 4 0. 5

r/z 1. 5

2.5

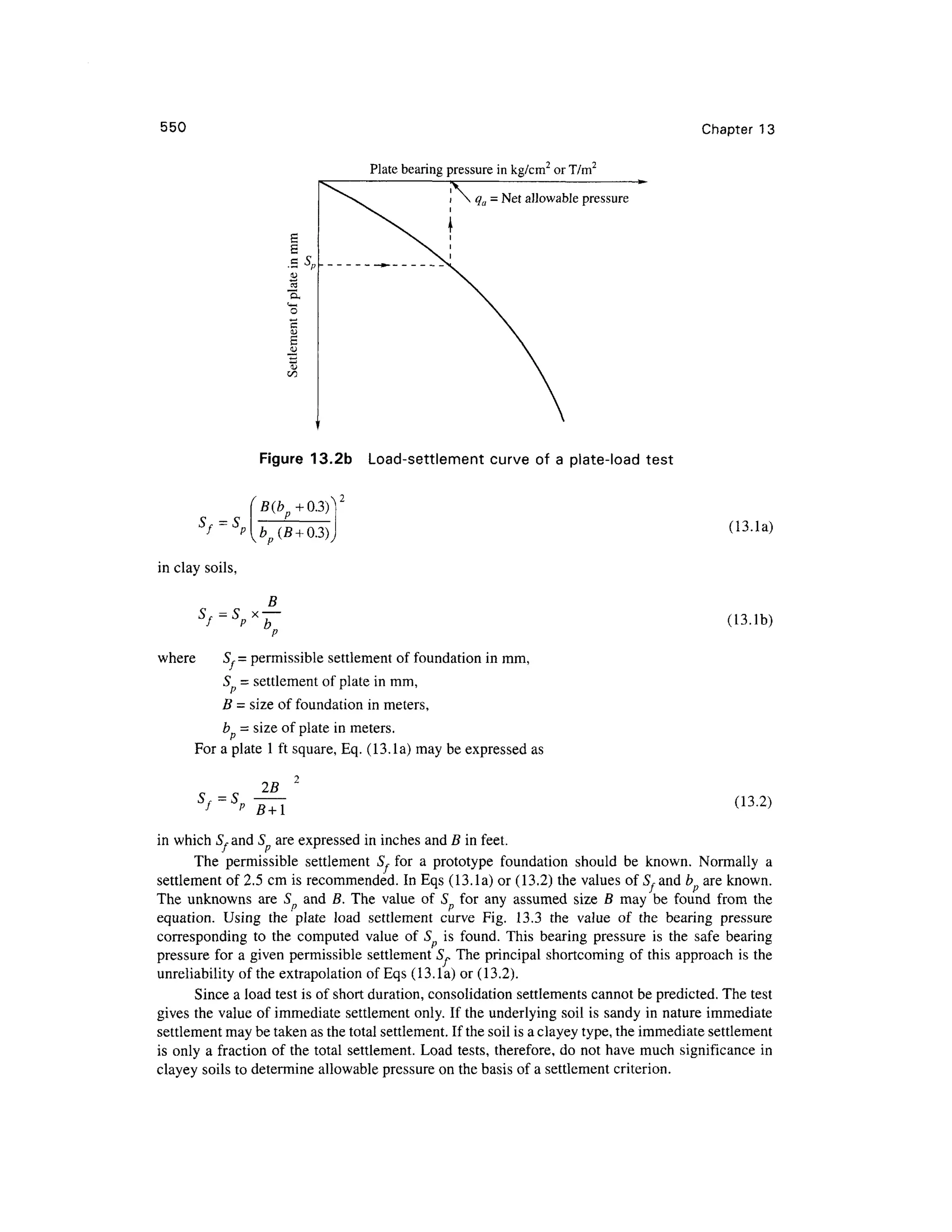

Figure 6.2 Value s of IB or /^for use in the Boussines q o r Westergaard formul a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-194-2048.jpg)

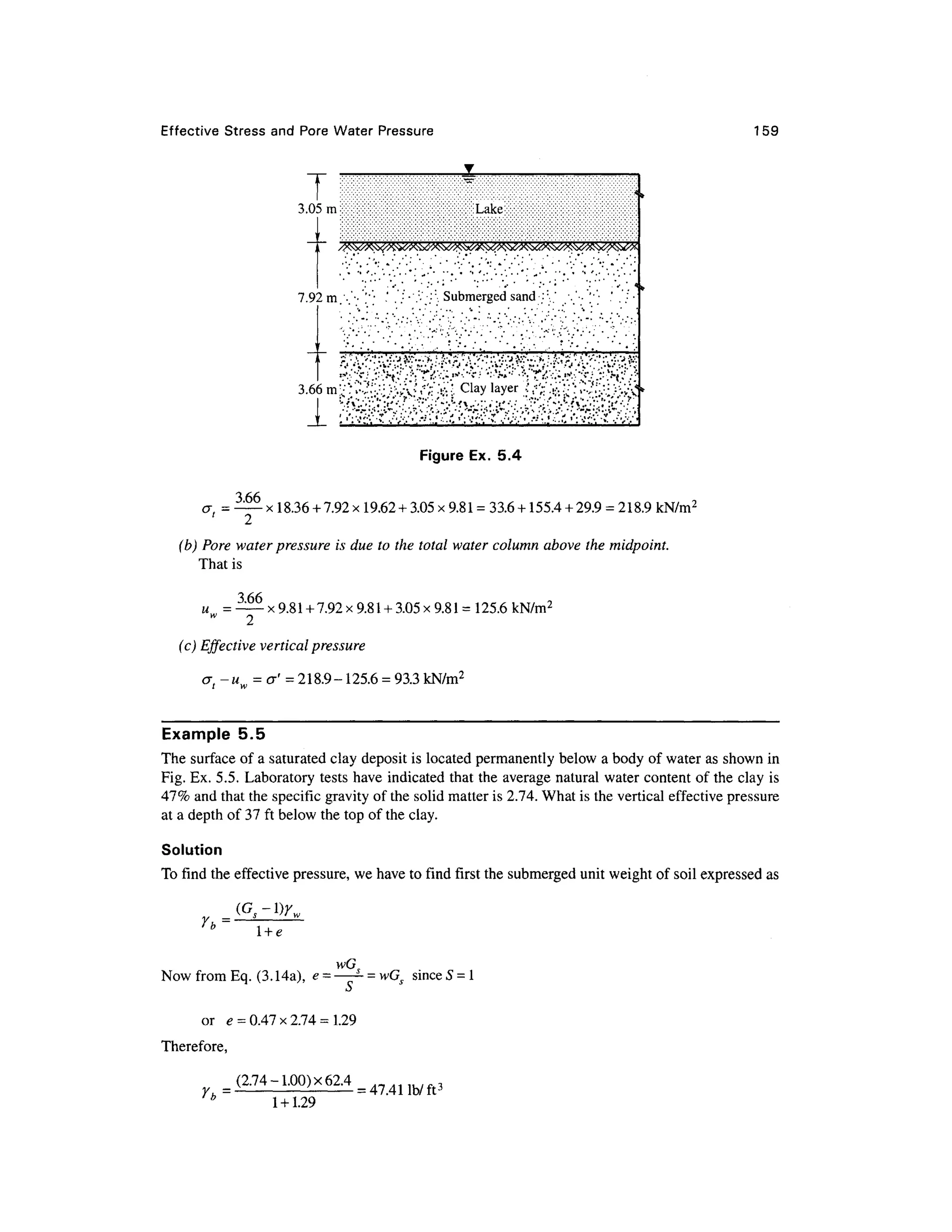

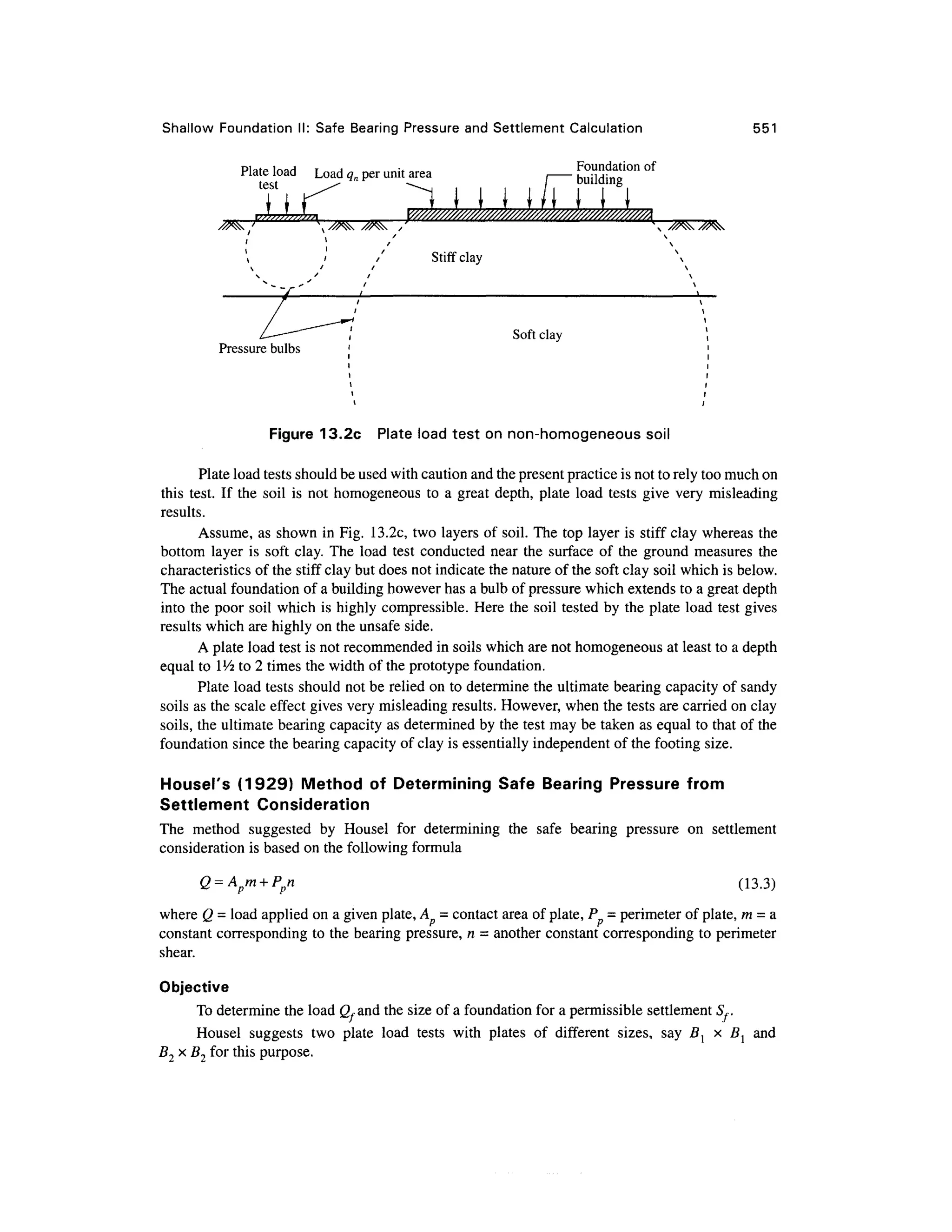

![178 Chapter 6

Location r/ z Boussinesq

I0 crJkPa )

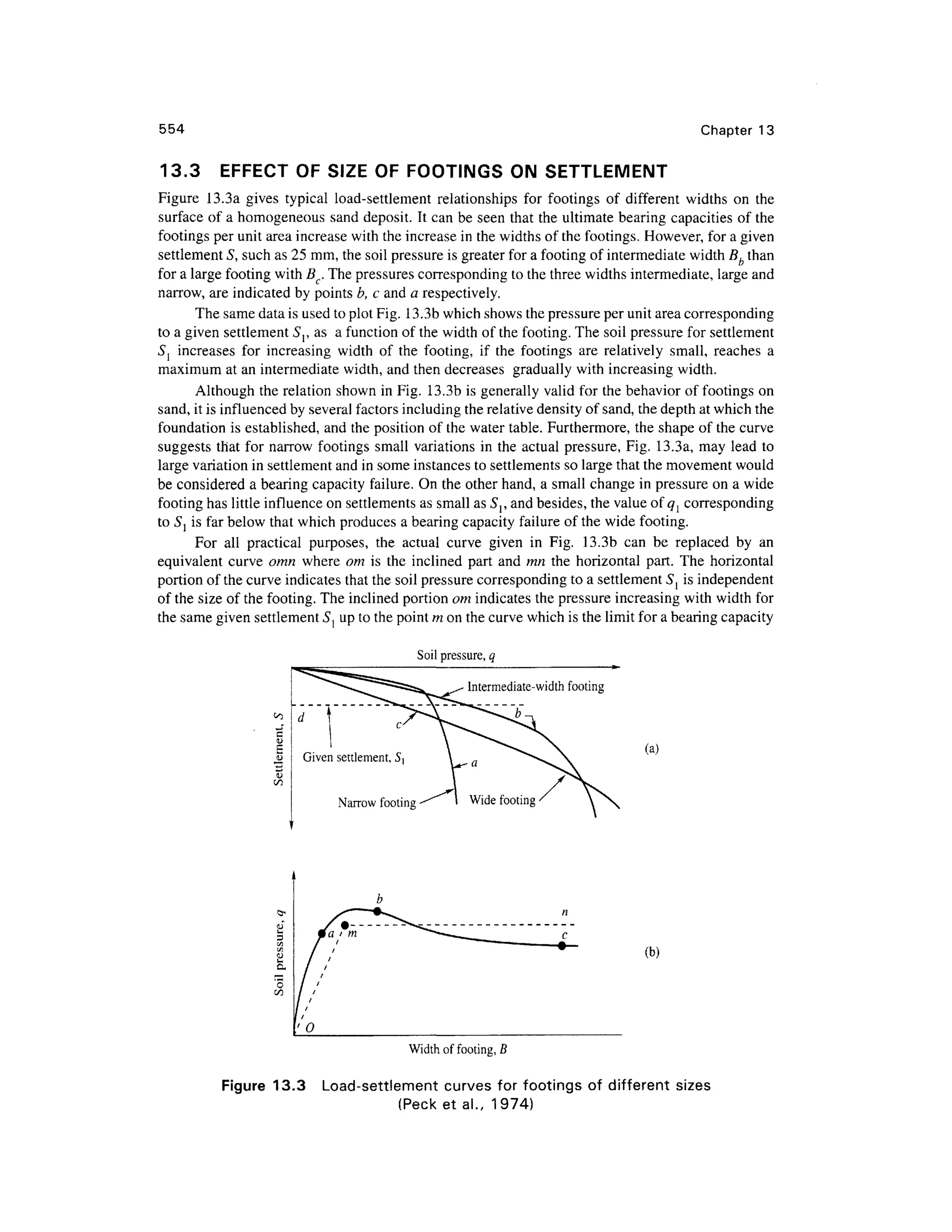

Westergaard

w

a/a, w

(0,0)

(6,0)

(0, 15 )

(6,15)

(10, 25 )

0

0.3

0.75

0.81

1.35

0.48

0.39

0.16

0.14

0.036

65

53

22

19

5

0.32

0.25

0.10

0.09

0.03

43

34

14

12

4

1.51

1.56

1.57

1.58

1.25

6.4 LIN E LOAD S

The basi c equatio n use d fo r computin g a, at an y poin t P i n a n elasti c semi-infinit e mass i s

Eq. (6.1) of Boussinesq. By applyin g the principle of his theory, the stresse s a t any poin t in the

mass due to a line load of infinite extent acting at the surface may be obtained. The state of stress

encountered i n thi s cas e i s tha t o f a plan e strai n condition . Th e strai n a t an y poin t P i n th e

F-direction parallel to the line load is assumed equal to zero. The stress c r norma l to the XZ-plane

(Fig. 6.3) is the same at all sections and the shear stresses o n these sections ar e zero. By applying

the theor y o f elasticity , stresse s a t an y poin t P (Fig . 6.3 ) ma y b e obtaine d eithe r i n pola r

coordinates o r i n rectangula r coordinates. Th e vertica l stres s a a t poin t P ma y b e writte n in

rectangular coordinate s a s

a =

z [ 1 + U/z)2

]2

z z

where, / i s the influence factor equal to 0.637 at x/z - 0 .

(6.4)

r — i x•" • + z

cos fc) =

Figure 6.3 Stresse s due to vertica l lin e loa d i n rectangular coordinate s](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-197-2048.jpg)

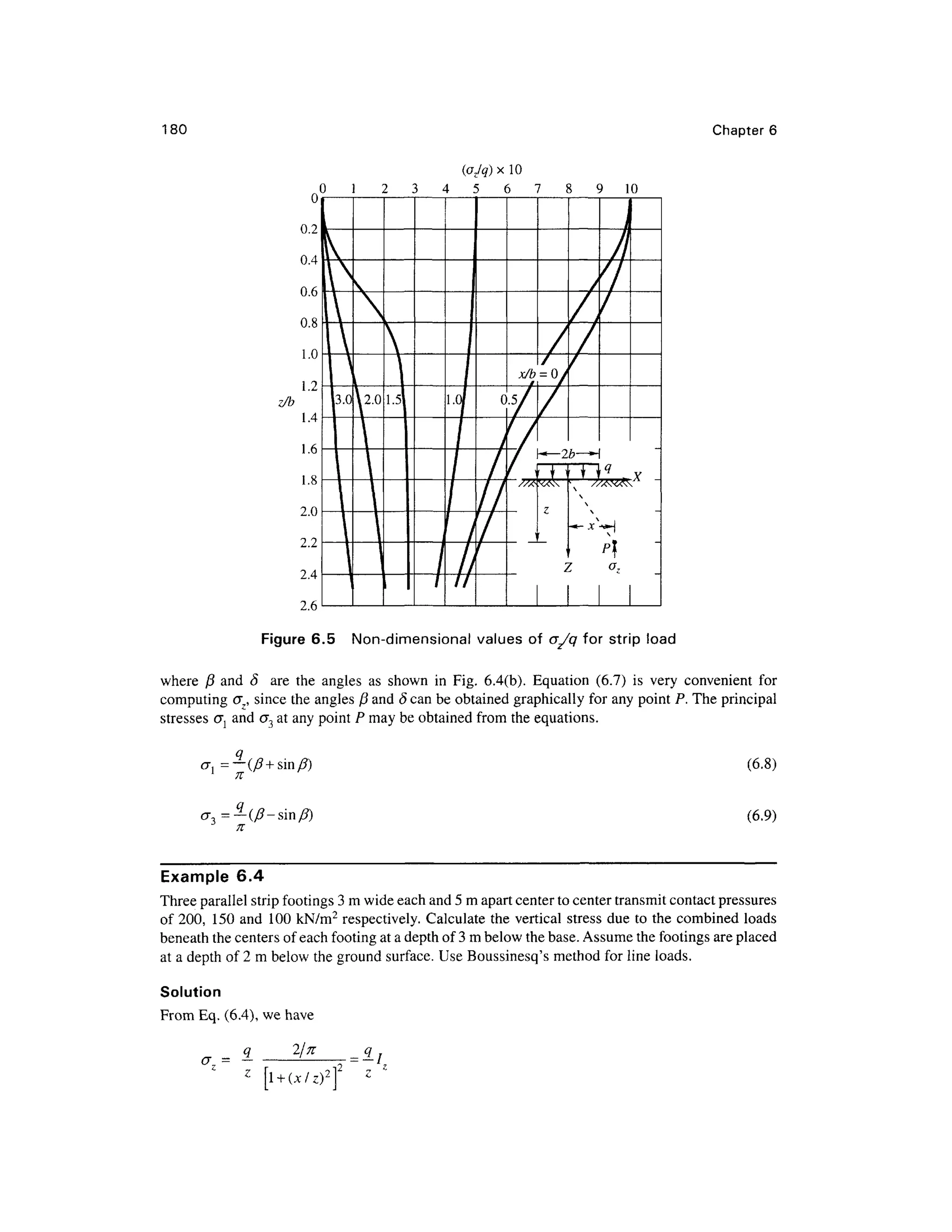

![Stress Distributio n in Soils du e to Surfac e Load s 179

6.5 STRI P LOAD S

The state of stress encountered i n this case also is that of a plane strain condition. Suc h conditions

are found fo r structures extended ver y much in one direction, suc h as strip and wall foundations,

foundations of retaining walls, embankments, dams and the like. For such structures the distribution

of stresses in any section (except for the end portions of 2 to 3 times the widths of the structures from

its end) will be the same as in the neighboring sections, provided that the load does no t change in

directions perpendicular to the plane considered.

Fig. 6.4(a ) shows a load q per unit area acting on a strip of infinite lengt h and of constant

width B. The vertical stress at any arbitrary point P due to a line load of qdx actin g at j c = x can be

written from Eq . (6.4) as

~

2q

n [(x-x) 2

+z2

]

(6.5)

Applying th e principl e o f superposition , th e tota l stres so~ z a t poin t P du e t o a stri p loa d

distributed over a width B(= 2b) may be written as

+b

[(x-x)2

+z2

}2 dx

or

-b

q , z

a = — tan" 1

1

n x-b

tan"

2bz(x2

-b2

-z2

)

x + b (6.6)

The non-dimensiona l value s o f cjjq ar e give n graphicall y i n Fig. 6.5 . Eq. (6.6 ) can b e

expressed i n a more convenient form as

=— [/?+sin/?cos(/?+2£)]

n

(6.7)

x O

(a) (b )

Figure 6.4 Stri p load](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-198-2048.jpg)

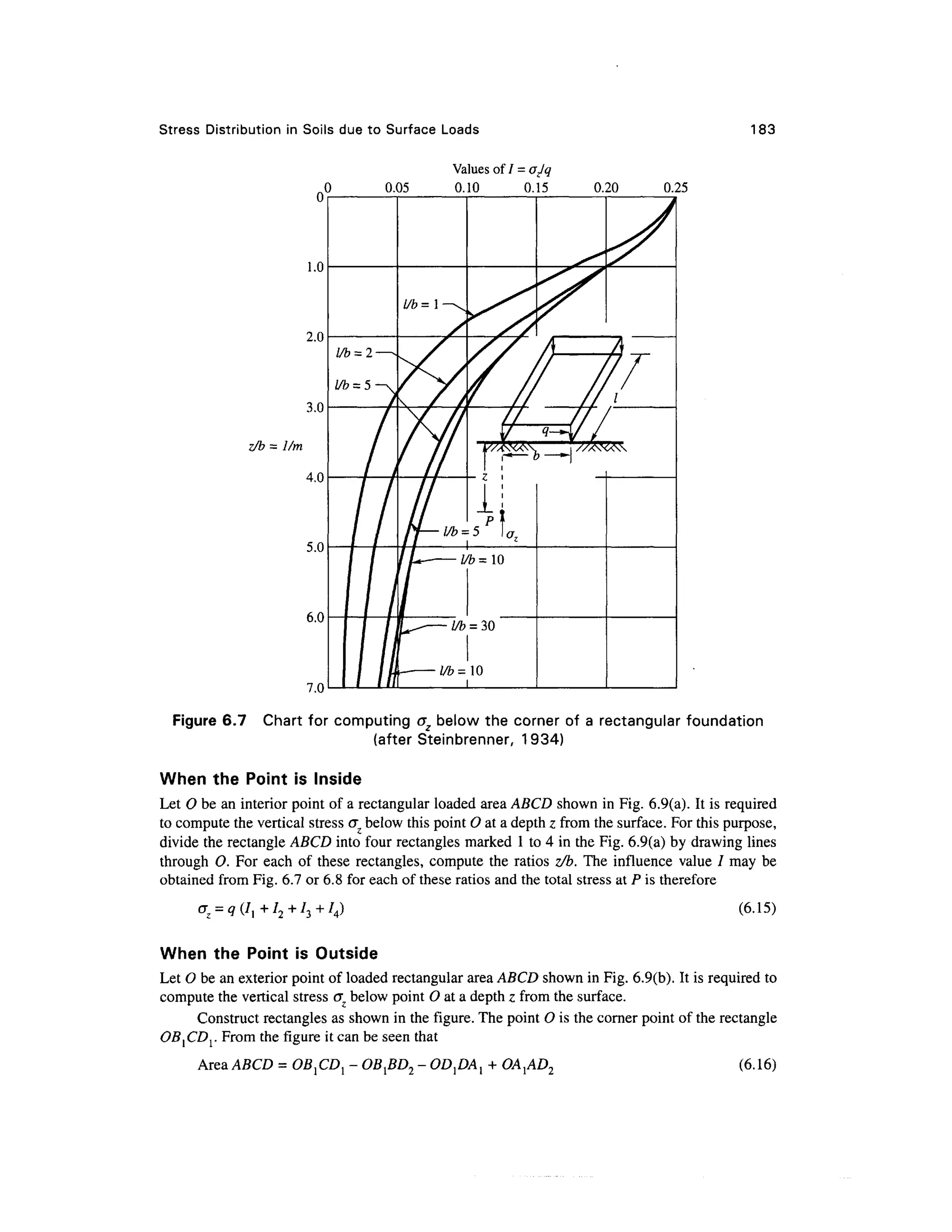

![Stress Distribution in Soils due to Surfac e Load s 18 5

The vertical stress a t point P located a t a depth z below poin t 0 du e to a surcharge q per

unit are a o f ABCD i s equa l t o the algebrai c su m o f the vertica l stresse s produce d b y loadin g

each one of the areas liste d on the right hand side of the Eq. (6.16) with q per unit of area. If /j

to /4 are the influence factors of each of these areas, th e total vertica l stres s is

(6.17)

Example 6. 5

ABCD i s a raf t foundatio n o f a multi-stor y building [Fig . 6 . 9(b) ] wherei n AB = 65.6 ft , an d

BC = 39.6 ft. The uniformly distributed load q over the raft is 73 10 lb/ft2

. Determine crz at a depth of

19.7 ft below point O [Fig. 6.9(b)] wherein AA, = 13.12 ft and A,0 = 19.68 ft. Use Fig. 6.8 .

Solution

Rectangles are constructed as shown in [Fig. 6.9(b)].

Area ABCD = OB}CDl - OB }BD2 - OD 1DA1 + OA1AD2

Rectangle

OB1CD1

OB1BD2

OD1DA1

OA{AD2

I

(ft)

85.28

85.28

52.72

19.68

b

(ft)

52.72

13.12

19.68

13.12

m

2.67

0.67

1.00

0.67

n

4.33

4.33

2.67

1.00

7

0.245

0.168

0.194

0.145

Per Eq. (6.17)

oz = q (/! - /2 - /3 + /4) =7310 (0.24 5 - 0.168 - 0.194 + 0.145) = 204.67 lb/ft2

The same value can be obtained using Fig. 6.7 .

Example 6. 6

A rectangula r raf t o f siz e 3 0 x 1 2 m founde d on th e groun d surface i s subjecte d t o a uniform

pressure of 150 kN/m2

. Assume the center of the area as the origin of coordinates (0,0), and corners

with coordinates (6 , 15) . Calculate the induced stress a t a depth of 20 m by the exact method at

location (0, 0).

Solution

Divide the rectangle 1 2 x 30 m into four equal parts of size 6 x 15m.

The stres s belo w th e corne r o f eac h footin g ma y b e calculate d b y usin g chart s give n in

Fig. 6.7 or Fig. 6.8. Here Fig. 6.7 is used.

For a rectangle 6 x 1 5 m, z Ib = 20/6 = 3.34, l/b = 15/6 = 2.5.

For z/b = 3.34, l/b = 2.5,< r Iq = 0.07

Therefore, o ; = 4cr = 4 x 0.01 q= 4 x 0.07 x 15 0 =42 kN/m2

.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-204-2048.jpg)

![186 Chapter 6

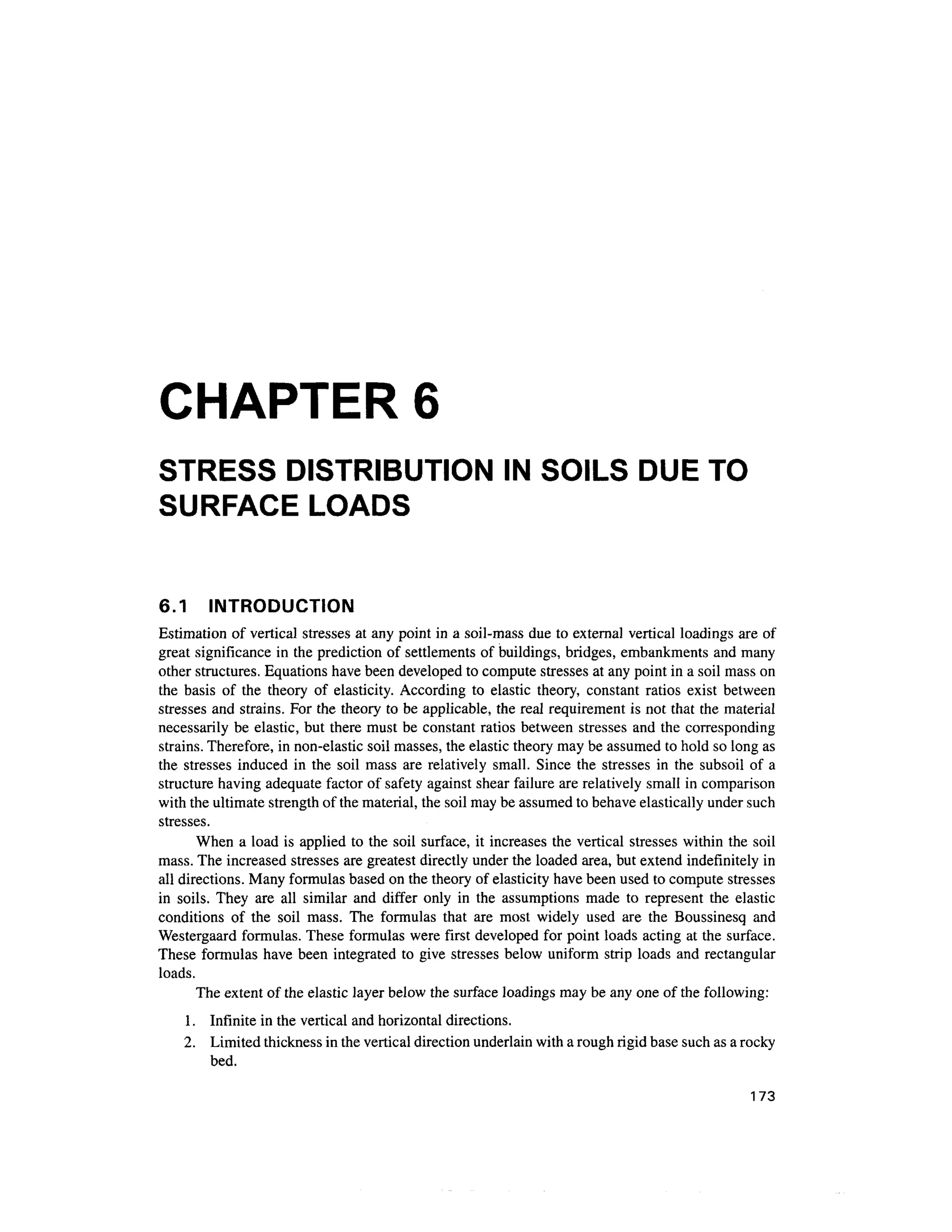

6.7 STRESSE S UNDE R UNIFORML Y LOADE D CIRCULA R FOOTIN G

Stresses Along the Vertica l Axis of Symmetry

Figure 6.1 0 show s a pla n an d sectio n o f th e loade d circula r footing . The stres s require d t o b e

determined a t any point P along the axis is the vertical stress cr,.

Let dA be an elementary area considered as shown in Fig. 6.10. dQ may be considered as the

point load acting on this area which is equal to q dA. We may write

(6.18)

The vertical stress d(J a t point P due to point load dQ may be expressed [Eq . (6. la)] as

3q

(6.19)

The integral form of the equation for the entire circular area may be written as

0=0 r= 0

3qz3

( f rdOdr

~^~ J J ( r 2 + z 2 ) 5 ,

0=0 r= 0

,3

On integration we have, (6.20)

o

R z

P

Figure 6.10 Vertica l stress unde r uniforml y loade d circular footin g](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-205-2048.jpg)

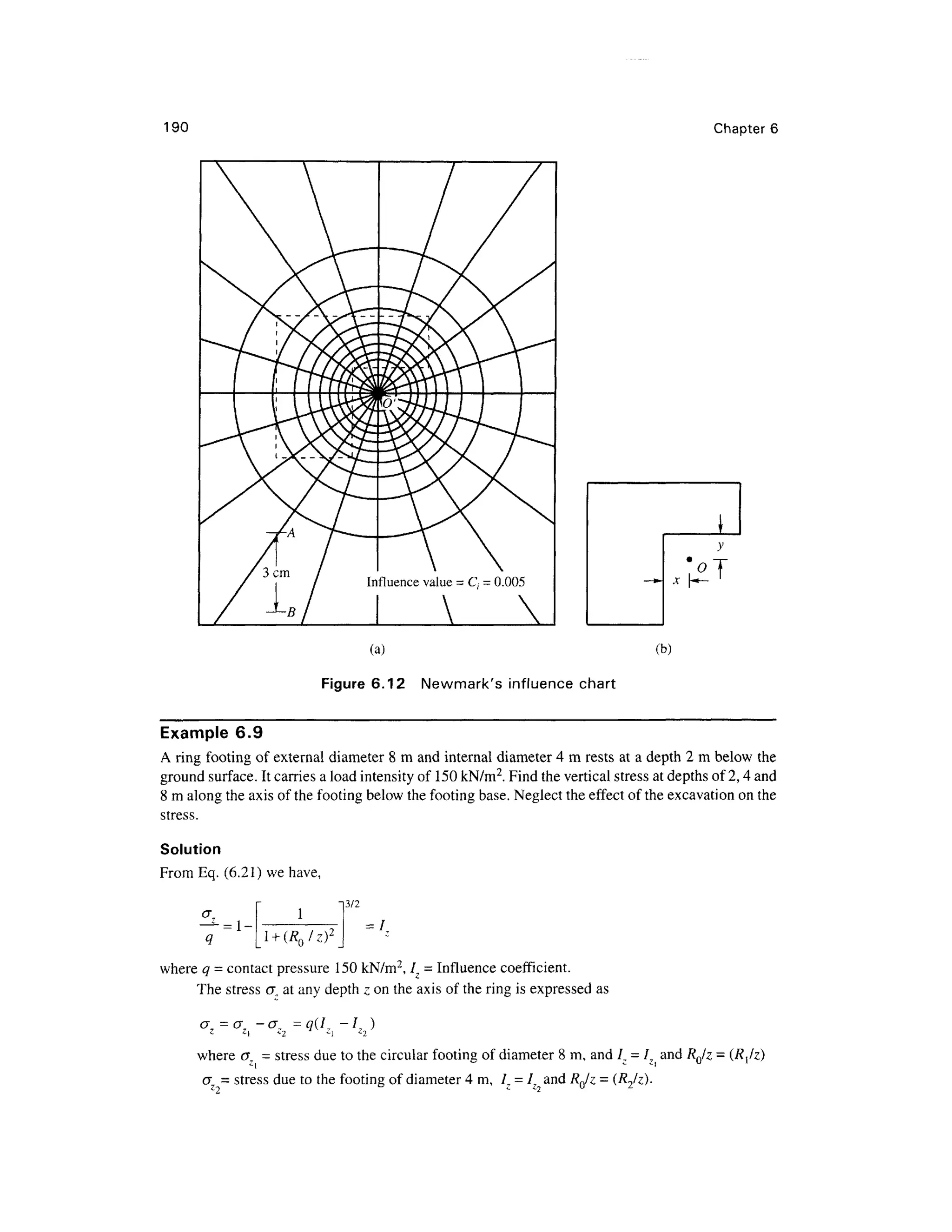

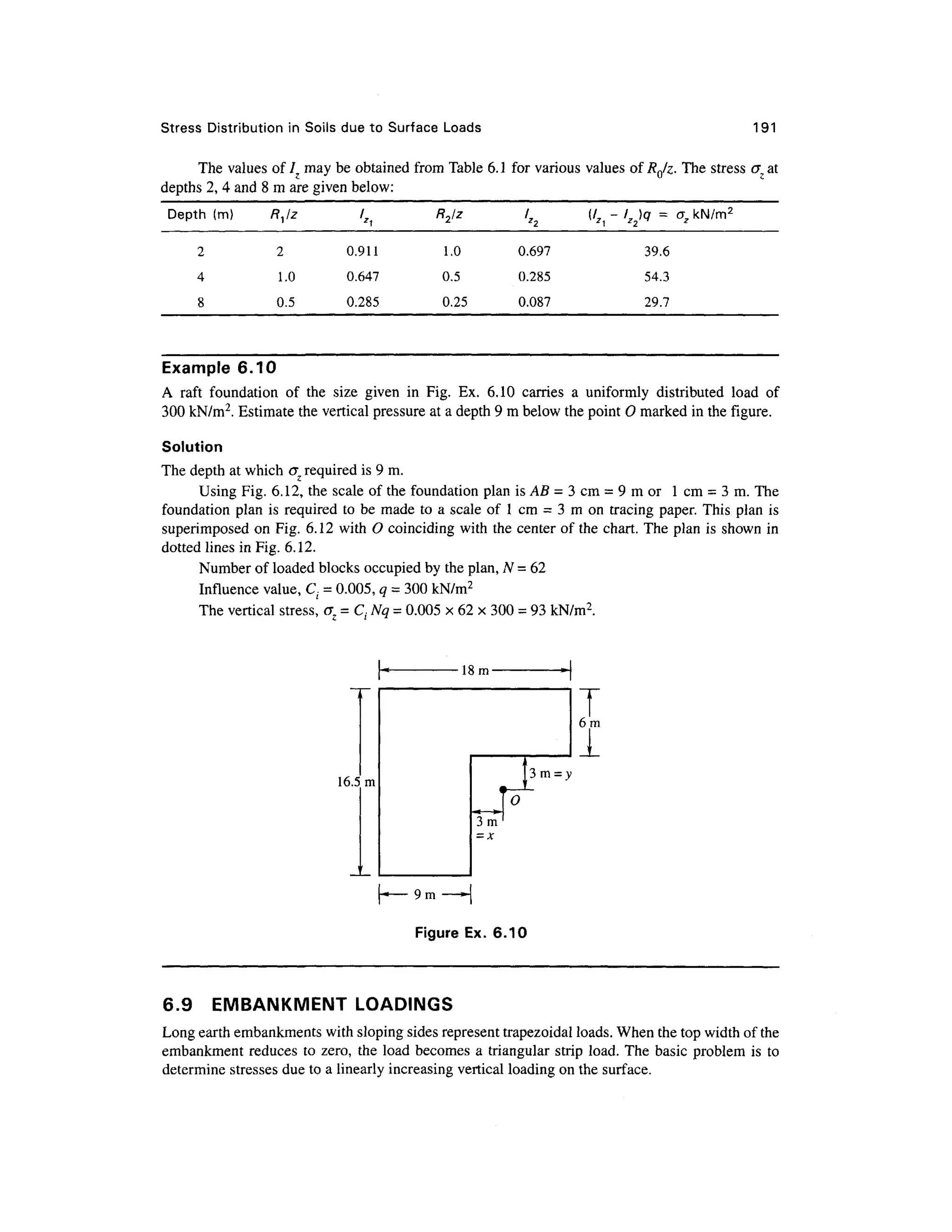

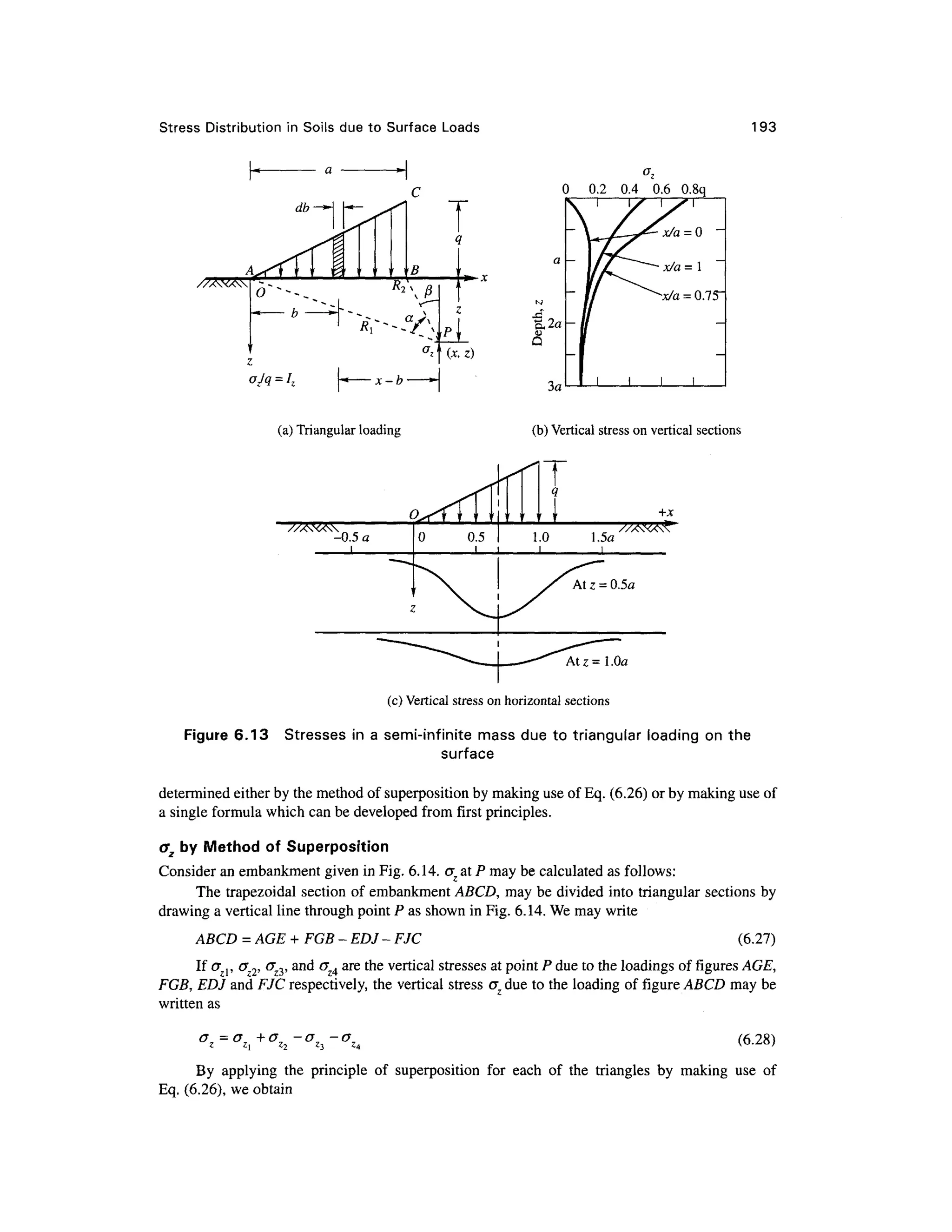

![192 Chapter s

Linearly Increasin g Vertical Loadin g

Fig. 6.13(a ) shows a linearly increasing vertica l loadin g startin g fro m zero at A to a finite value q

per unit length at B. Consider a n elementary stri p of width db at a distance b from A. The load per

unit length may be written as

dq - (q/d) b db

Ifdq i s considered a s a line load on the surface, th e vertica l stres s dcr, at P [Fig . 6 . 1 3(a)]

due t o d q ma y b e writte n fro m Eq . (6.4 ) a s

dcr,=— —

'

Therefore,

er

b=a

2q

[(x-,

/ 9

on integration, o - = 77" ~~ a-sm20 = 07 (6.25 )

z

2/T a y z

where 7 i s non-dimensional coefficien t whose value s for various values of xla and zla are given in

Table 6.2 .

If th e point P lies in the plane BC [Fig. 6.13(a)], then j 8 = 0 at jc = a. Eq. (6.25) reduces to

vz=-(a) (6.26 )

<• n

Figs. 6.13(b ) an d (c ) sho w th e distributio n of stres s e r o n vertica l an d horizonta l section s

under th e actio n o f a triangular loadin g a s a function of q. The maximu m vertica l stres s occur s

below th e center of gravity of the triangular load as shown in Fig. 6.13(c) .

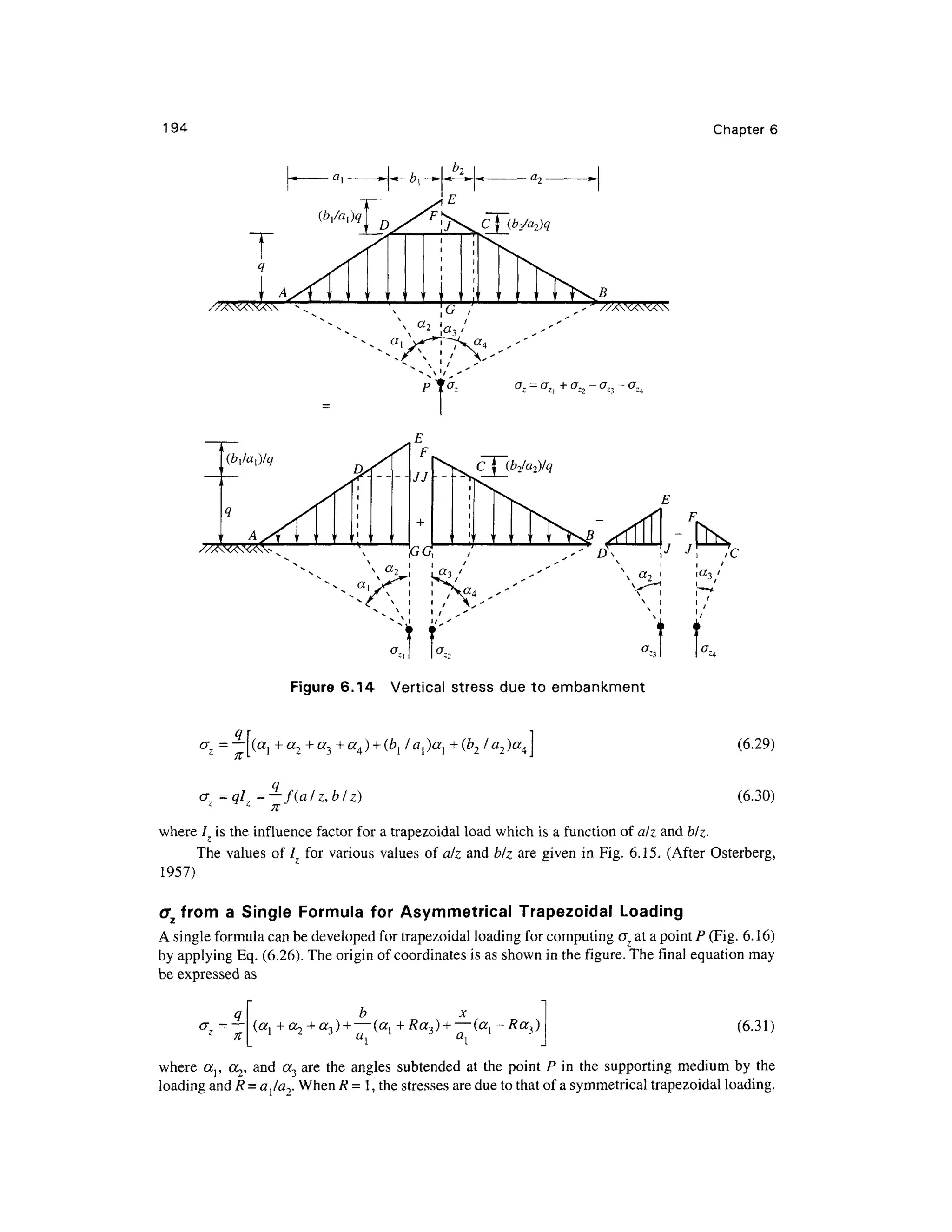

Vertical Stres s Du e to Embankmen t Loadin g

Many time s i t ma y b e necessar y t o determin e th e vertica l stres s e r beneat h roa d an d railwa y

embankments, an d als o beneat h eart h dams . Th e vertica l stres s beneat h embankment s ma y b e

Table 6. 2 / fo r triangula r loa d (Eq . 6.25 )

x/a

-1.500

-1.00

0.00

0.50

0.75

1.00

1.50

2.00

2.50

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.50

0.75

0.50

0.00

0.00

0.00

0.5

0.002

0.003

0.127

0.410

0.477

0.353

0.056

0.017

0.003

1.0

0.014

0.025

0.159

0.275

0.279

0.241

0.129

0.045

0.013

2/fl

1.5

0.020

0.048

0.145

0.200

0.202

0.185

0.124

0.062

0.041

2

0.033

0.061

0.127

0.155

0.163

0.153

0.108

0.069

0.050

4

0.051

0.060

0.075

0.085

0.082

0.075

0.073

0.060

0.049

6

0.041

0.041

0.051

0.053

0.053

0.053

0.050

0.050

0.045](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-211-2048.jpg)

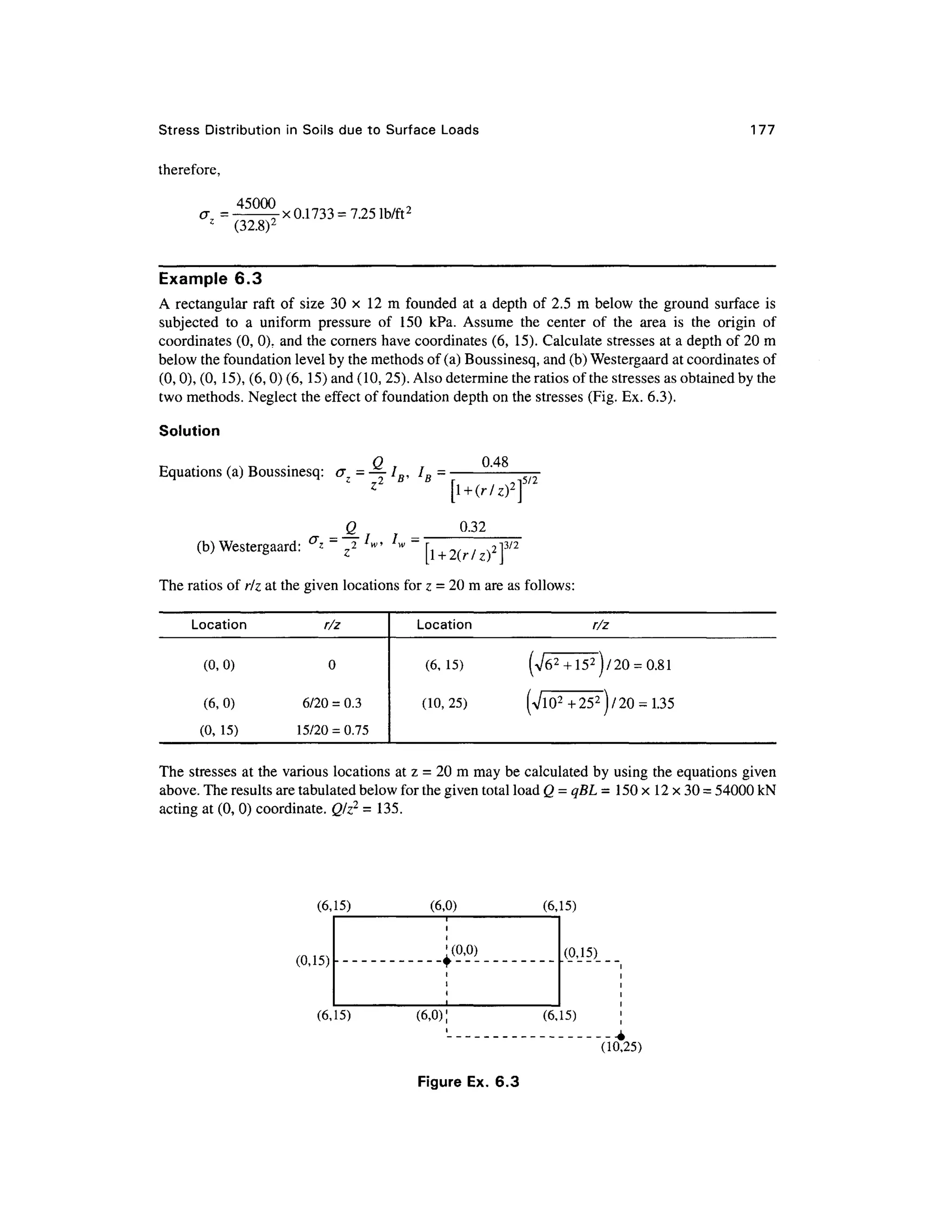

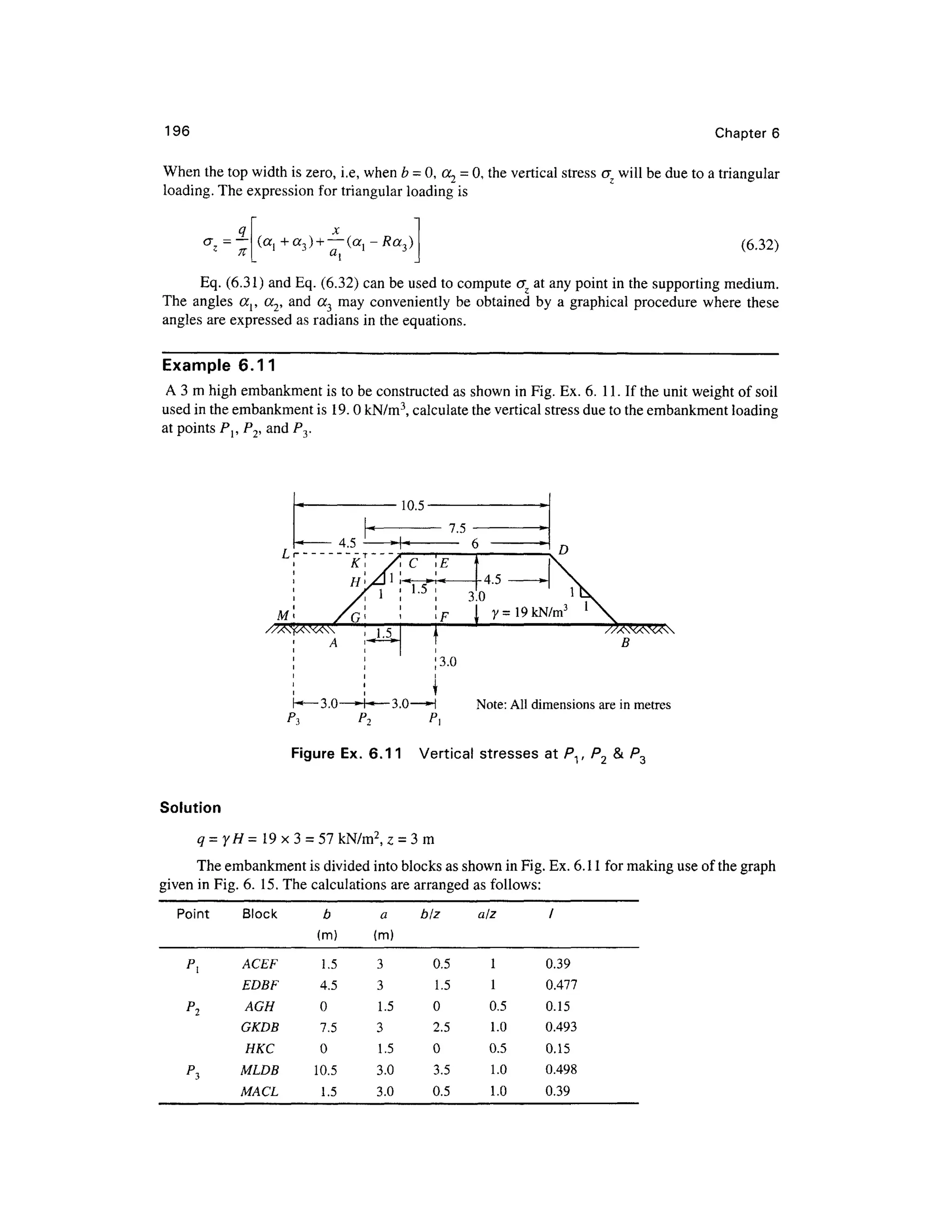

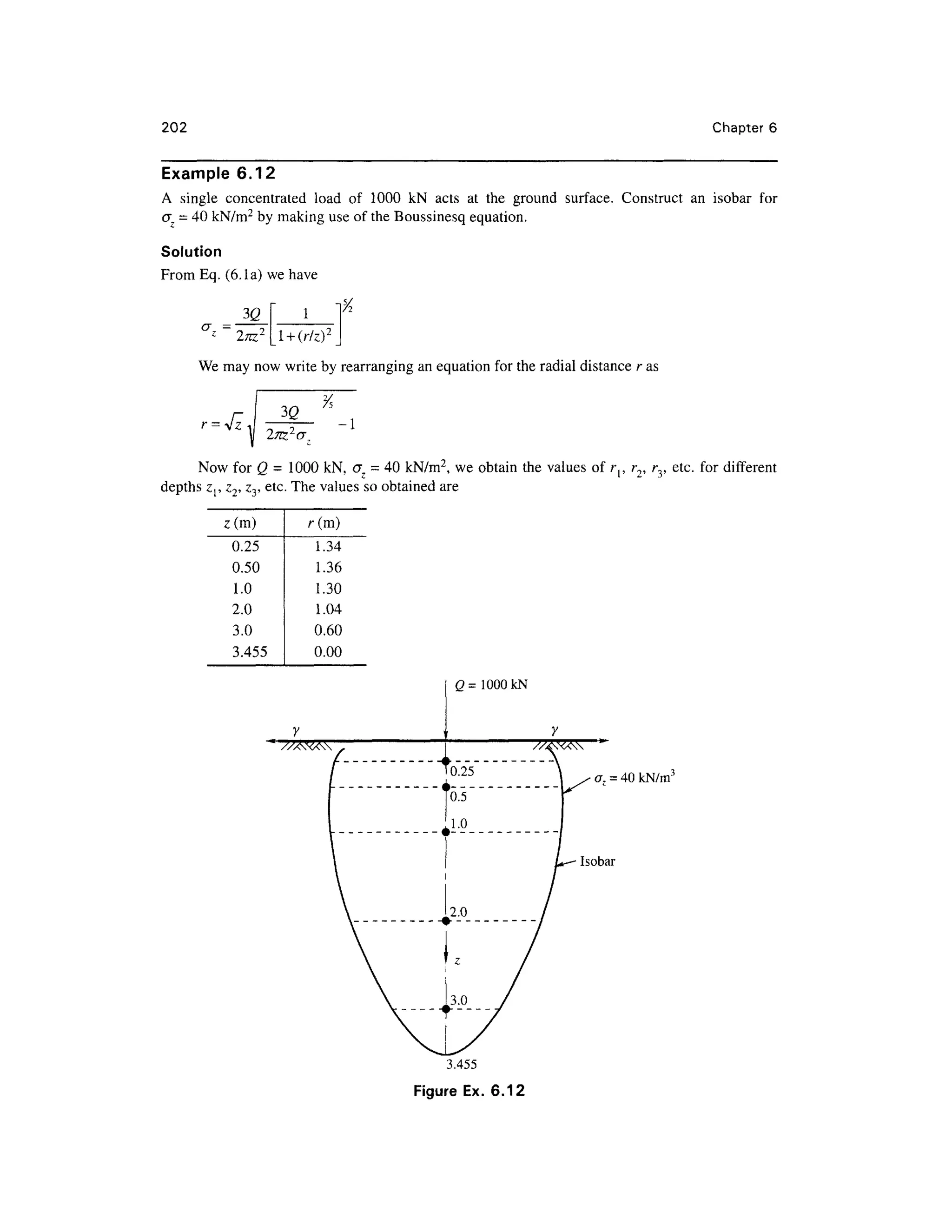

![Stress Distributio n in Soils due to Surfac e Loads 199

Lines of

equal vertical

pressure or

isobars

Figure 6.19 Bul b o f pressure

Significant Dept h

In hi s openin g discussio n o n

settlement o f structure s a t th e

First Internationa l Conferenc e

on Soi l Mechanic s an d

Foundation Engineering (held in

1936 a t Harvar d Universit y i n

Cambridge, Mass , USA) ,

Terzaghi stresse d th e

importance o f th e bul b o f

pressure an d it s relationshi p

with th e sea t o f settlement . As

stated earlie r w e may dra w any

number of isobars fo r any given

load system , but the on e tha t is

of practica l significanc e i s th e

one which encloses a soil mass which is responsible for the settlement of the structure. The depth of

this stressed zone may be termed as the significant depth DS which is responsible for the settlement

of the structure. Terzaghi recommended that for all practical purposes one can take a stress contour

which represents 20 per cent of the foundation contact pressure q, i.e, equal to Q.2q. The depth of

such an isobar can be taken as the significant depth Ds which represents the seat of settlement for

the foundation. Terzaghi's recommendation wa s based o n his observation that direct stresse s are

considered o f negligible magnitude when they are smaller than 20 per cent of the intensity of the

applied stress from structural loading, and that most of the settlement, approximately 80 per cent of

the total, takes place at a depth less than Ds. The depth Ds is approximately equal to 1. 5 times the

width of square or circular footings [Fig. 6.20(a)].

If several loaded footing s are spaced closely enough, the individual isobars of each footing

in questio n woul d combin e an d merg e int o on e larg e isoba r o f the_intensit y a s show n i n

[Fig. 6.20(b)]. The combined significan t dept h D i s equal to about 1. 5 B .

az = Q.2q

D<=.5B Stresse d zone

Isobar

(a) Significant depth of stressed zone

for single footing

Isobar

Combined stressed zone

(b) Effect o f closely placed footings

Figure 6.2 0 Significan t dept h o f stressed zon e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-218-2048.jpg)

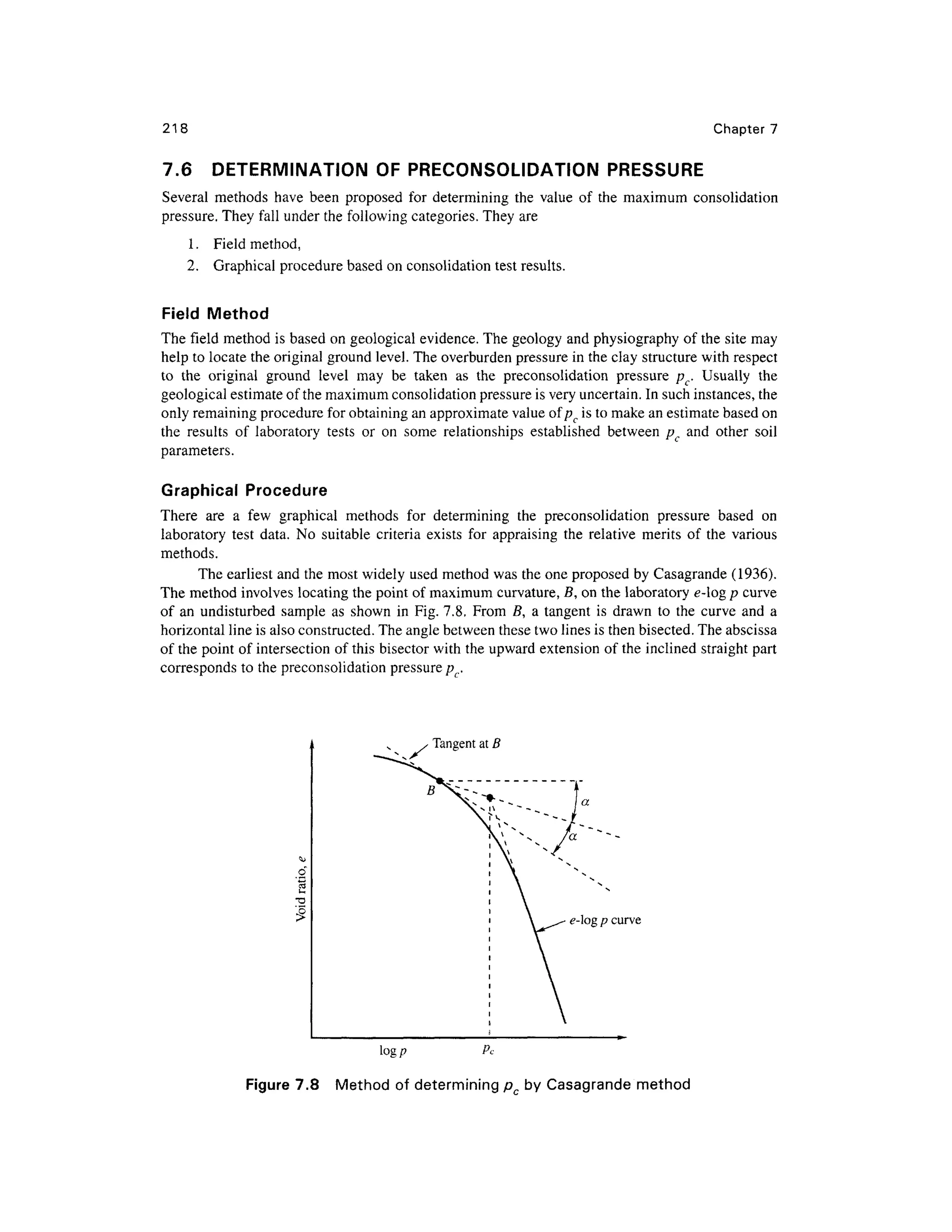

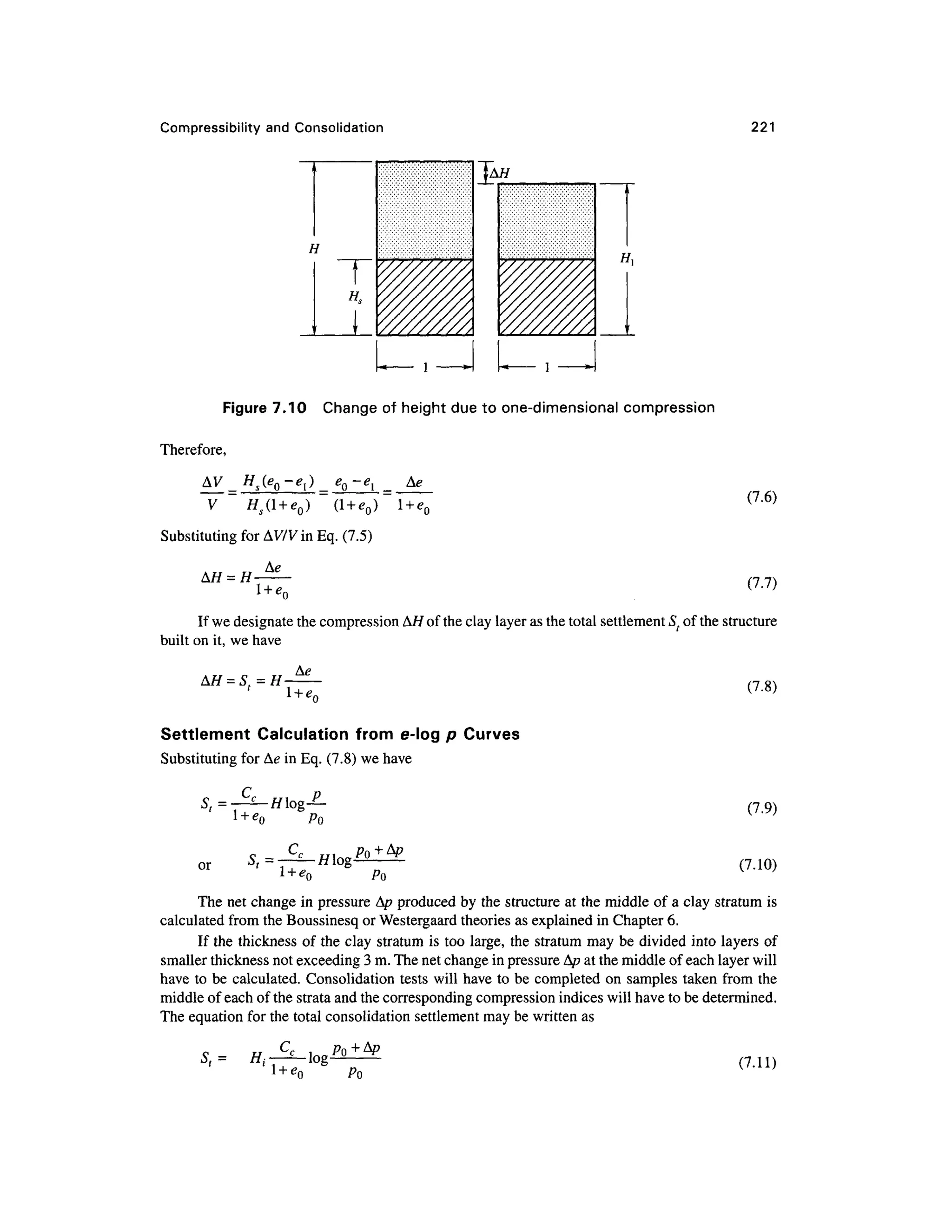

![Compressibility an d Consolidation 21 9

7.7 e-log p FIEL D CURVE S FO R NORMALLY CONSOLIDATE D AN D

OVERCONSOLIDATED CLAYS O F LOW TO MEDIU M SENSITIVIT Y

It has been explaine d earlie r wit h reference t o Fig. 7.5, tha t the laborator y e-lo g p curv e of an

undisturbed sample does not pass through point A and always passes below the point. It has been

found fro m investigatio n tha t th e incline d straigh t portio n o f e-log p curve s o f undisturbe d or

remolded sample s of clay soil intersect a t one point at a low void ratio and corresponds t o 0.4eQ

shown as point C in Fig. 7.9 (Schmertmann, 1955). It is logical to assume the field curve labelled as

Kf shoul d als o pas s throug h thi s point . Th e fiel d curv e ca n b e draw n fro m poin t A, havin g

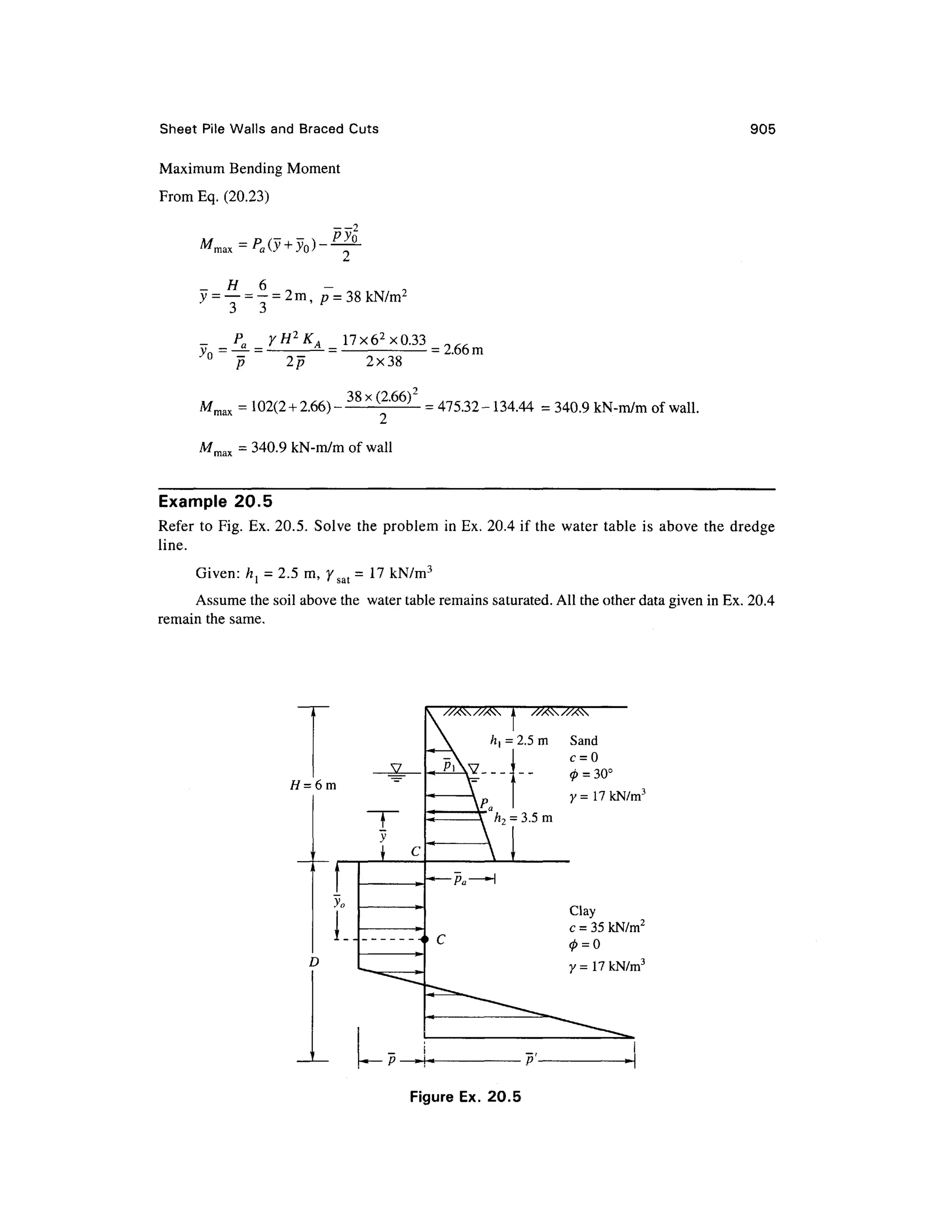

coordinates (e Q, /?0), which corresponds t o the in-situ condition of the soil. The straight line AC in

Fig. 7.9(a) gives the field curve AT,for normally consolidated clay soil of low sensitivity.

The field curve for overconsolidated cla y soil consists of two straight lines, represented by

AB and BC in Fig. 7.9(b). Schmertmann (1955) has shown that the initial section AB of the field

curve is parallel to the mean slope MNof th e rebound laboratory curve. Point B is the intersection

point of the vertical line passing through the preconsolidation pressure pc on the abscissa an d the

sloping line AB. Sinc e point C is the intersection of the laboratory compressio n curv e and the

horizontal line at void ratio 0.4eQ, line BC can be drawn. The slope of line MN whic h i s the slope

of the rebound curve is called the swell index Cs.

Clay o f Hig h Sensitivit y

If th e sensitivit y St i s greate r tha n abou t 8 [sensitivit y is define d a s th e rati o o f unconfme d

compressive strengths of undisturbed and remolded soi l samples refer to Eq. (3.50)], then the clay

is said to be highly sensitive. The natural water contents of such clay are more than the liquid

limits. Th e e-log p curv e K u fo r a n undisturbe d sampl e o f suc h a clay wil l hav e th e initia l

branch almost flat as shown in Fig. 7.9(c) , and after this it drops abruptly into a steep segment

indicating there b y a structural breakdown o f the clay suc h that a slight increase of pressur e

leads t o a large decrease in void ratio. The curve then passes through a point of inflection a t d

and its slope decreases . If a tangent is drawn at the point of inflection d, it intersects th e line

eQA a t b . The pressur e correspondin g t o b (p b) i s approximatel y equa l t o tha t a t whic h th e

structural breakdown take s place . I n areas underlain by soft highl y sensitive clays, the exces s

pressure Ap over the layer should be limited to a fraction of the difference of pressure (pt-p0).

Soil o f this type belongs mostl y to volcanic regions .

7.8 COMPUTATIO N O F CONSOLIDATION SETTLEMEN T

Settlement Equation s for Normall y Consolidate d Clays

For computin g th e ultimat e settlemen t o f a structur e founde d o n cla y th e followin g dat a ar e

required

1. Th e thickness of the clay stratum, H

2. Th e initial void ratio, eQ

3. Th e consolidation pressur e pQ or pc

4. Th e field consolidation curve K,

The slope of the field curve K.on a semilogarithmic diagram is designated a s the compression

index Cc (Fig. 7.9 )

The equation for Cc may be written as

C e

°~e e

°~e A g

Iogp-logp0 logp/ Po logp/p Q

(7

'4)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-238-2048.jpg)

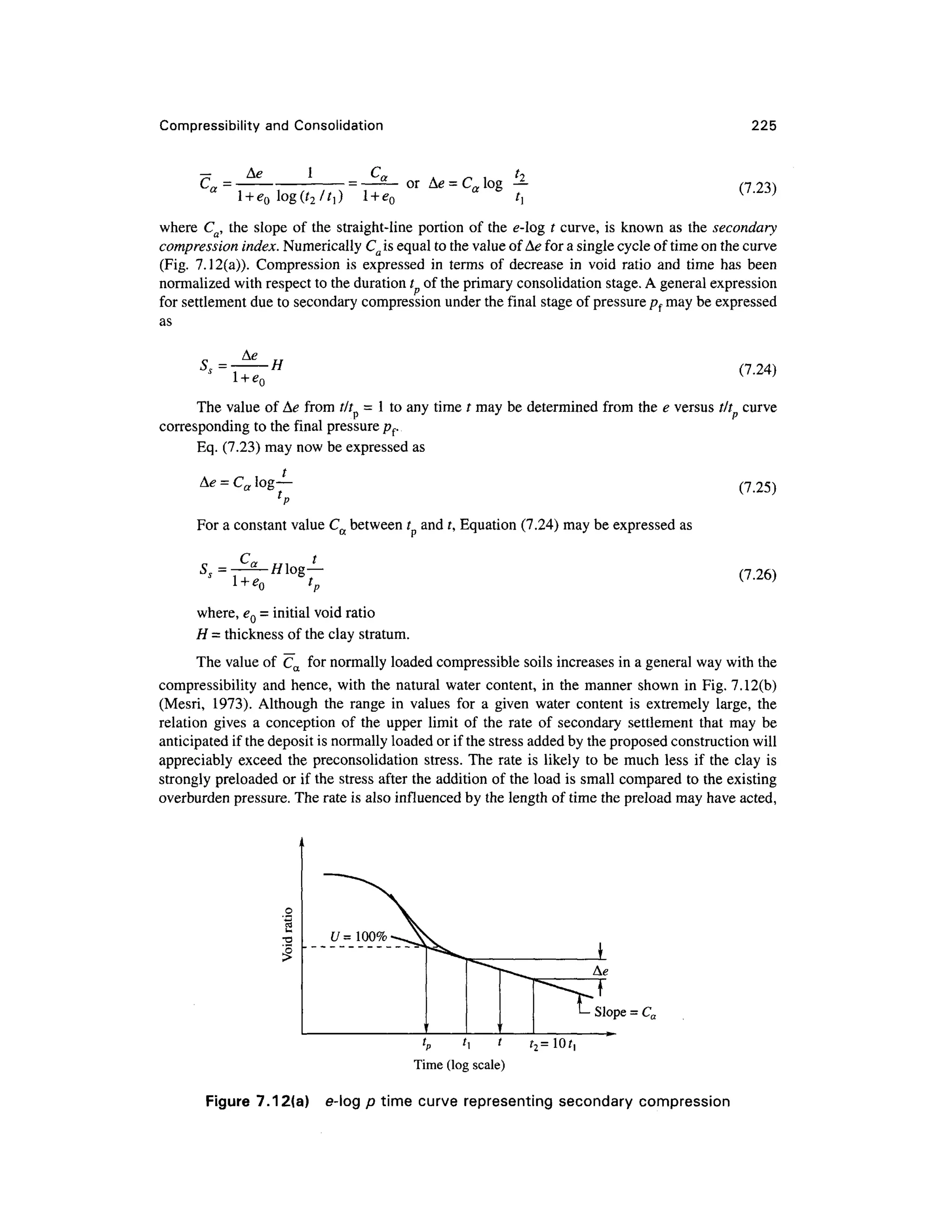

![Compressibility and Consolidation 22 3

Settlement Calculatio n from e-log p Curv e fo r Overconsolidate d Cla y Soi l

Fig. 7.9(b) gives the field curve Kffor preconsolidate d clay soil. The settlement calculation depends

upon the excess foundation pressure Ap over and above the existing overburden pressure pQ.

Settlement Computation , i f pQ + A/0 < pc (Fig . 7.9(b))

In such a case, us e the sloping line AB. If Cs = slope of this line (also called the swell index), we

have

a

c =

log(p

o+Ap)

(7.14a )

Po

or A * = C, log

^ (7.14b )

By substituting for A< ? in Eq. (7.8) , we have

(7.15a)

Settlement Computation , if p0 < pc < p0 + Ap

We may write from Fig. 7.9(b)

Pc

(715b)

In this case the slope of both the lines AB and EC in Fig. 7.9(b) are required to be considered.

Now the equation for St may be written as [from Eq. (7.8) and Eq. (7.15b)]

CSH p c C CH

log— + — -—log

* Pc

The swell index Cs « 1/ 5 to 1/10 Cc can be used as a check.

Nagaraj an d Murthy (1985) have proposed the following equation for Cs as

C = 0.046 3 -^ - G

100 s

where wl = liquid limit, Gs = specific gravity of solids.

Compression Inde x C c — Empirica

l Relationship s

Research workers in different part s of the world have established empirica l relationships between

the compression index C and other soil parameters. A few of the important relationships are given

below.

Skempton's Formul a

Skempton (1944) established a relationship between C, and liquid limits for remolded clay s as

Cc = 0.007 (wl - 10 ) (7.16 )

where wl is in percent.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-242-2048.jpg)

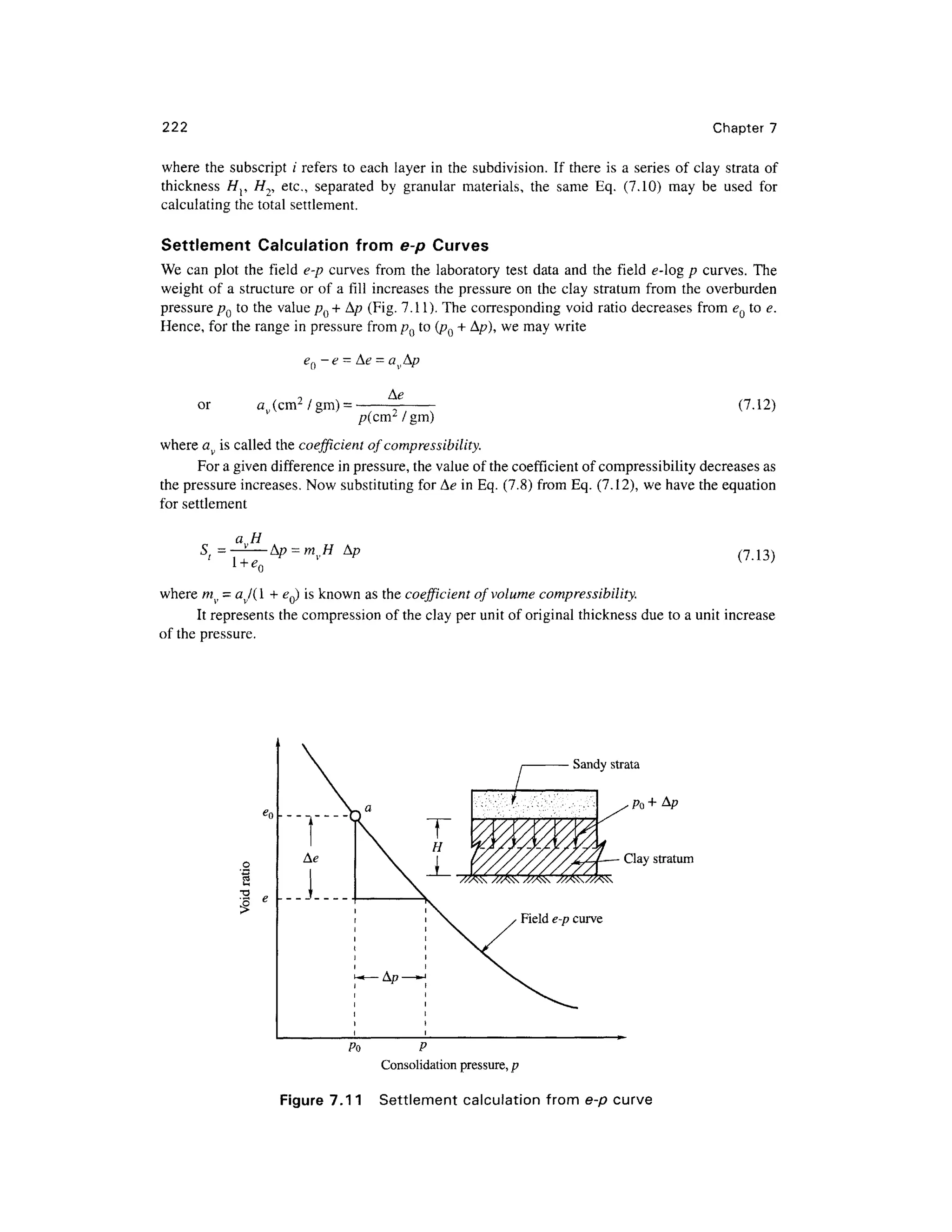

![Compressibility and Consolidation 22 9

Solution

Per Eq. (7.7), the compression of the fill may be calculated as

where AH = the compression, Ae = change in void ratio, eQ = initial void ratio, HQ = thickness of fill.

Substituting, A/ f = L0

~0

-8

x 32.8 = 3.28 ft .

Example 7. 3

A stratum of normally consolidated clay 7 m thick is located a t a depth 12 m below ground level.

The natura l moisture content of the clay is 40.5 pe r cent and its liquid limit is 48 per cent. The

specific gravity of the solid particles is 2.76. The water table is located at a depth 5 m below ground

surface. The soil is sand above the clay stratum. The submerged unit weight of the sand is 1 1 kN/m3

and the same weighs 1 8 kN/m3

above the water table. The average increase in pressure at the center

of the clay stratum is 120 kN/m2

due to the weight of a building that will be constructed on the sand

above the clay stratum. Estimate the expected settlemen t of the structure.

Solution

1 .Determinatio n of e and yb for the clay [Fig. Ex. 7.3]

W

=1x2.76x1 =2.76 g

405

W = — x2.7 6 =1.118 g

w

10 0

„

r

vs i

= UI& + 2.76 = 3.878 g

W

' 1 Q - J / 3

Y, = -

= -

=1-83 g/c m

' 2.11 8

Yb = (1.83-1 ) = 0.83 g/cm 3

.

2. Determinatio n of overburden pressure p Q

PO = yh

i+ Y2h

i+ yA°r

P0= 0.83x9.81x3.5 + 11x7 + 18x5 = 195.5 kN/m 2

3. Compressio n inde x [Eq. 11.17 ]

Cc = 0.009(w, -10) = 0.009 x(48 -10

) =0.34](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-248-2048.jpg)

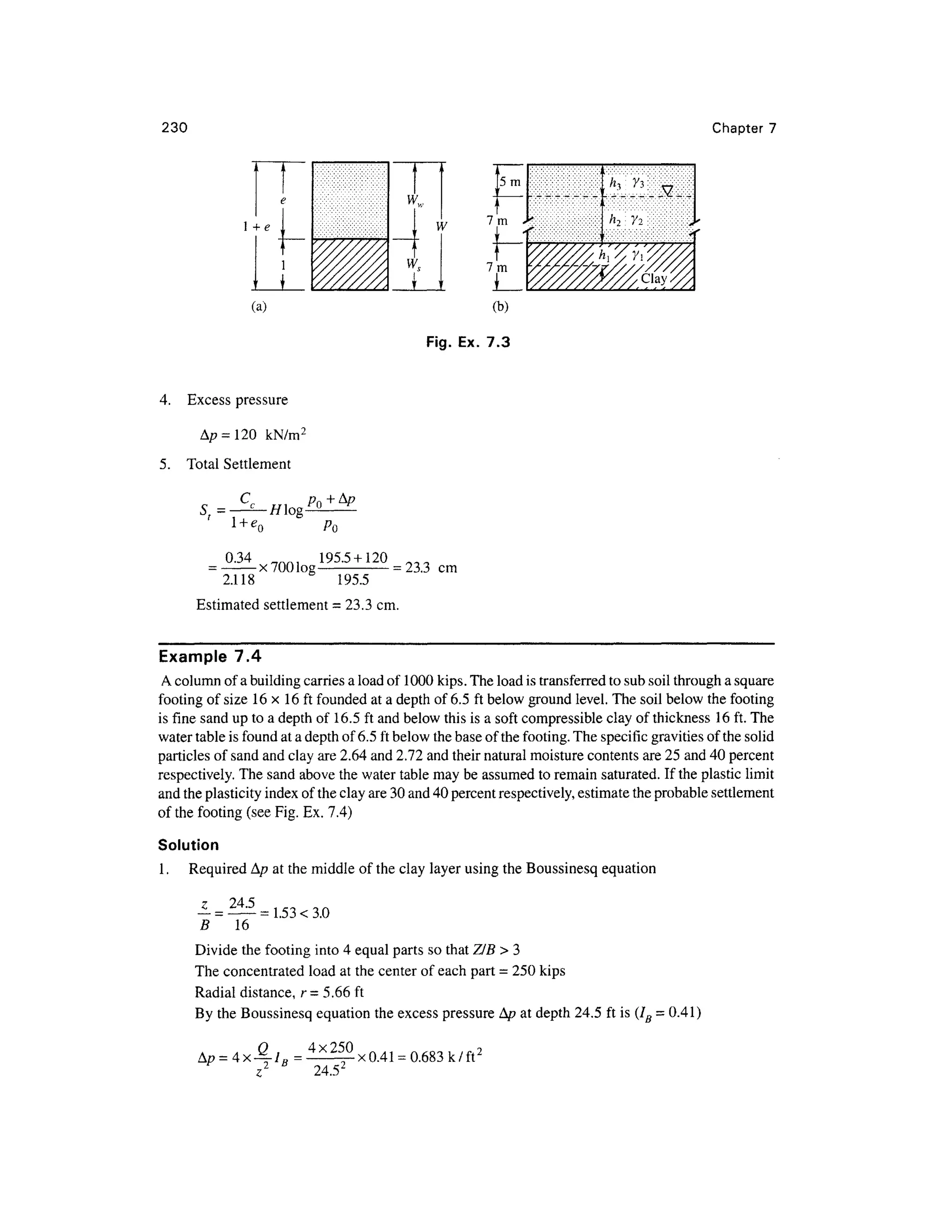

![232 Chapte r 7

Solution

For calculating settlement [Eq. (7.15a)]

C p n + A/?

S = — —H log^ -

-wher e &p = 120 kN /m2

l + eQ p Q

From Eq. (7.17), Cr = 0.009 (w, - 10 ) =

0.009(45 - 10 ) =

0.32

wG

From Eq. (3. 14a), e Q = -

= wG = 0.40 x 2.78 =1.1 1sinc e S =1

tJ

Yb, the submerged unit weight of clay, is found as follows

MG.+«.) = 9*1(2.78 + Ul) 3

' ^" t 1 , 1 . 1 1 1

l + eQ l + l.ll

Yb=Y^-Yw = 18.1-9.8 1 =8.28 kN/m3

The effective vertical stress pQ a t the mid height of the clay layer is

pQ = 4.60 x 17.6 + 6 x10.4 + —x 8.28 = 174.8 kN / m2

_ 0.32x7.60 , 174. 8 + 120

Now S t = -

log -

=0.26m =26 cm

1

1+1.1 1 174. 8

Average settlement

= 2 6 cm.

Example 7. 6

A soil sampl e ha s a compression inde x of 0.3. I f the void ratio e at a stress o f 2940 Ib/ft2

i s 0.5,

compute (i ) the void ratio if the stress i s increased to 4200 Ib/ft2

, an d (ii) the settlement o f a soil

stratum 1 3 ft thick.

Solution

Given: C c = 0.3, el = 0.50, /?, = 2940 Ib/ft2

, p2 = 4200 Ib/ft2

.

(i) No w from Eq. (7.4),

p — p

C i

%."-)

C = l

- 2

—

or e 2 = e

]-c

substituting the known values, we have,

e- = 0.5 -0.31og - 0.454

2

294 0

(ii) Th e settlement per Eq. (7.10) is

c c

c „ , Pi 0.3x13x12 , 420 0

S = — —//log— = -

log -

=4.83 m

.

pl 1. 5 294 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-251-2048.jpg)

![264 Chapte r 8

If the sides of the cylindrical specimen are not acted on by the horizontal pressure <7 3, the load

required t o caus e failur e i s calle d th e unconfme d compressiv e strengt h qu. I t i s obviou s tha t a n

unconfmed compressio n test can be performed onl y on a cohesive soil. According to Eq. (8.20), the

unconfmed compressive strength q i s equal to

<T = a — 2r N f 8 71

u

i y «-] </> (o.Zj)

If 0 = 0, then qu = 2c (8.24a )

or the shear strength

s = c= —(8.24b )

Eq. (8.24b ) show s one o f the simples t way s of determining the shea r strengt h of cohesiv e

soils.

8.9 MOH R CIRCL E O F STRESS

Squaring Eqs. (8.8) and (8.9) and adding, we have

i2 / _ ^ x 2

+ ^ = I " 2 j + *ly (8.25 )

Now, Eq. (8.25) is the equation of a circle whose center has coordinate s

and whose radius is — i/(c7 - c r ) -

2v vy

'

The coordinates of points on the circle represent the normal and shearing stresses on inclined

planes at a given point. The circle is called th e Mohr circle of stress, after Mohr (1 900), who firs t

recognized thi s usefu l relationship . Mohr's metho d provide s a convenient graphical metho d fo r

determining

I . Th e normal and shearing stress on any plane through a point in a stressed body .

2. Th e orientation of the principal planes if the normal and shear stresses on the surface of the

prismatic elemen t (Fig . 8.6 ) ar e known . The relationship s ar e vali d regardles s o f th e

mechanical propertie s o f th e material s sinc e onl y th e consideration s o f equilibriu m are

involved.

If th e surface s o f th e elemen t ar e themselve s principa l planes , th e equatio n fo r th e Moh r

circle of stress may be written as

T + oy -- -

= - y -- ( 8.26)

The center of the circle has coordinates T- 0 , and o=(a{ + (T3)/2, and its radius is (<Jl - (T 3)/2.

Again from Mohr's diagram, the normal and shearing stresses on any plane passing through a point

in a stressed body (Fig. 8.7) may be determined if the principal stresses cr l and (J3 are known. Since

<7j andO" 3 are always known in a cylindrical compression test, Mohr's diagram is a very useful too l

to analyze stresses on failure planes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-283-2048.jpg)

![Shear Strengt h of Soi l 265

8.10 MOH R CIRCL E O F STRESS WHE N A PRISMATI C ELEMEN T

IS SUBJECTED TO NORMA L AND SHEA R STRESSE S

Consider first the case of a prismatic element subjected to normal and shear stresses as in Fig. 8.8(a).

Sign Conventio n

1. Compressiv e stresses are positive and tensile stresses are negative.

2. Shea r stresses are considered a s positive if they give a clockwise moment about a point

above the stressed plane as shown in Fig. 8.8(b), otherwise negative.

The norma l stresse s ar e take n a s absciss a an d th e shea r stresse s a s ordinates . I t i s

assumed the norma l stresses c r , cr an d the shear stress r ( T = T ) acting o n the surface of

x y xy xy yx

the elemen t ar e known . Tw o point s P l an d P 2 ma y no w b e plotte d i n Fig . 8.8(b) , whos e

coordinates are

If the points P} and P2 are joined, the line intersects the abscissa at point C whose coordinates

are [(0,+op/2,0].

Minor principal

> a

i

plane

(a) A prismatic element subjected to normal and shear stresses

(ax + ay)/2

+ ve

(b) Mohr circle of stress

Figure 8.8 Moh r stres s circl e for a general case](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-284-2048.jpg)

![266 Chapte r 8

Point O is the origin of coordinates for the center of the Mohr circle of stress. With center C

a circle may now be constructed with radius

This circl e whic h passes throug h points Pl an d P2 i s called th e Mohr circle o f stress. The

Mohr circle intersects the abscissa at two points E and F . The major and minor principal stresses

are ol ( = OF) and cr 3 (= OE) respectively .

Determination o f Norma l an d Shea r Stresse s o n Plan e A A [Fig . 8.8(a) ]

Point P{ o n the circle of stress in Fig. 8. 8(b) represents the state of stress on the vertical plane of the

prismatic element ; similarl y point P2 represent s th e stat e o f stres s o n th e horizonta l plan e o f th e

element. If from point P{ a line is drawn parallel to the vertical plane, it intersects the circle at point PQ

and if from th e point P2 on the circle, a line is drawn parallel to the horizontal plane, this line also

intersects the circle at point PQ . The point PQ so obtained is called the origin of planes or the pole. If

from the pole PQ a line is drawn parallel to the plane AA in Fig. 8.8(a) to intersect the circle at point P3

(Fig. 8.8(b)) then the coordinates o f the point give the normal stress cran d the shear stress Ton plane

AA as expressed by equations 8.8 and 8.9 respectively. This indicates that a line drawn from the pole PQ

at any angle a t o the cr-axi s intersects the circle at coordinates tha t represent the normal and shear

stresses on the plane inclined at the same angle to the abscissa.

Major an d Mino r Principa l Planes

The orientations of the principal planes may be obtained by joining point PQ to the points E and F

in Fig 8.8(b). PQ F is the direction of the major principal plane on which the major principal stres s

dj acts ; similarly PQ E is the direction o f the minor principal plane on which the minor principal

stress<7 3 acts. It is clear from the Mohr diagram that the two planes PQ E and PQ F intersect at a right

angle, i.e., angle EPQ F = 90°.

8.1 1 MOH R CIRCL E O F STRESS FO R A CYLINDRICA L SPECIME N

COMPRESSION TES T

Consider the case of a cylindrical specimen of soil subjected to normal stresses<7 j and<J 3 which are

the major and minor principal stresses respectively (Fig . 8.9 )

From Eqs. (8.14 ) and (8.15), we may write

2 2

Again Eq. (8.27) is the equation of a circle whose center has coordinate s

<7, + CT , (7 , — (J-.

<J = — - -

-and T =

0 and whose radius is

/O /-*^T

(8.27)

2 2

A circle with radius (o{ - cr 3)/2 with its center C on the abscissa a t a distance of (al + cr3)/2

may be constructed a s shown in Fig. 8.9 . This i s the Mohr circle of stress. The majo r and mino r

principal stresses are shown in the figure wherein cr, = OF and<7 3 = OE.

From Fig. 8.8 , we can writ e equations for cf j an d<7 3 and T max as follows

±](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-285-2048.jpg)

![276 Chapte r 8

Simplifying, w e have

(o[ -o'3)f = (o{ + o'3 ) sin(/)' + 2c' cos 0' (8.39 )

8.17 STRESS-CONTROLLE D AN D STRAIN-CONTROLLE D TESTS

Direct shear tests or triaxial compression tests may be carried out by applying stresses or strains at

a particularly known rate. When the stress is applied at a constant rate it is called a stress-controlled

test an d whe n th e strai n is applie d a t a constan t rate i t i s calle d a strain-controlled test. Th e

difference betwee n the two types of tests may be explained with respect t o box shear tests.

In the stress-controlled test [Fig. 8.15(a)] the lateral load Fa which induces shear is gradually

increased unti l complete failur e occurs. Thi s ca n be done b y placin g weights o n a hanger o r by

filling a counterweighte d bucke t o f origina l weigh t W a t a constan t rate . Th e shearin g

displacements are measured by means of a dial gauge G as a function of the increasing load F . The

shearing stress at any shearing displacement, is

where A i s the cross sectional are a o f the sample. A typical shape o f a stress-strain curv e of the

stress-controlled test is shown in Fig. 8.15(a).

A typical arrangement of a box-shear test apparatus for the strain-controlled test is shown in

Fig. 8.15(b) . The shearin g displacements ar e induced and controlled i n such a manner that they

occur at a constant fixed rate. This can be achieved by turning the wheel either by hand or by means

of any electrically operate d motor so that horizontal motion is induced through the worm gear B.

The dial gauge G gives the desired constant rate of displacement. The bottom of box C is mounted

on frictionless rollers D. The shearing resistance offered to this displacement by the soil sample is

measured b y the proving ring E. The stress-strain curves for this type of test have the shape shown

in Fig. 8.15(b).

Both stress-controlled and strain-controlled types of test are used in connection with all the

direct triaxia l and unconfined soi l shea r tests . Strain-controlled tests ar e easier to perform an d

have the advantage of readily giving not only the peak resistance as in Fig. 8.1 5 (b ) but also the

ultimate resistance which is lower than the peak suc h as point b in the same figure, whereas th e

stress controlled gives only the peak values but not the smaller values after the peak is achieved.

The stress-controlled test is preferred only in some special problem s connecte d wit h research.

8.18 TYPE S O F LABORATOR Y TEST S

The laboratory tests on soils may be on

1. Undisturbe d samples, or

2. Remolde d samples .

Further, the tests may be conducted on soils that are :

1 .Full y saturated, or

2. Partiall y saturated.

The type of test to be adopted depend s upon how best we can simulate the field conditions.

Generally speaking, the various shear tests for soils may be classified as follows:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-295-2048.jpg)

![280 Chapte r 8

Table 8.1 Typica l value s of 0 and (j) u fo r granula r soil s

Types of soi l

Sand: rounded grains

Loose

Medium

Dense

Sand: angular grains

Loose

Medium

Dense

Sandy gravel

0 deg

28 to 30

30 to 35

35 to 38

30 to 35

35 to 40

40 to 45

34 to 48

0u deg

26 to 30

30 to 35

33 to 36

intermediate values of pressure, the shearing force causes a decrease in the void ratio of loose sand

and an increase i n the void ratio of dense sand. Fig 8.16(b) shows how the volume of dense sand

decreases u p t o a certai n valu e o f horizonta l displacemen t an d wit h furthe r displacemen t th e

volume increases , wherea s i n th e cas e o f loose san d th e volum e continues to decreas e wit h an

increase in the displacement. In saturated san d a decrease of the void ratio is associated with an

expulsion of pore water, and an increase with an absorption of water. The expansion of a soil due to

shear a t a constant valu e of vertica l pressure i s called dilatancy. At som e intermediat e stat e o r

degree of density in the process of shear, the shear displacement does not bring about any change in

volume, that is, density. The density of sand at which no change in volume is brought about upon

the applicatio n o f shea r strain s i s calle d th e critical density. Th e porosit y an d voi d rati o

corresponding t o th e critica l densit y are calle d th e critical porosity an d th e critical void ratio

respectively.

By plottin g the shea r strength s corresponding to the state of failure i n the differen t shea r test s

against the normal pressure a straight line is obtained for loose sand and a slightly curved line for dense

sand [Fig . 8.16(c)] . However , fo r al l practica l purposes , th e curvatur e for th e dens e san d ca n b e

disregarded an d an average line may be drawn. The slopes of the lines give the corresponding angles of

friction 0 of the sand. The general equation forthe lines may be written as

s = <J tan(f)

For a given sand, the angle 0 increases wit h increasing relative density. For loose san d it is

roughly equal to the angle of repose, defined as the angle between the horizontal and the slope of a

heap produced by pouring clean dry sand from a small height. The angle of friction varie s with the

shape of the grains. Sand samples containing well graded angular grains give higher values of 0 as

compared to uniformly graded san d with rounded grains. The angl e of friction</ > for dense sand at

peak shear stress is higher than that at ultimate shear stress. Table 8.1 gives some typical values of

0 (at peak) and 0 M (at ultimate).

Triaxial Compression Test

Reconstructed sand samples at the required density are used for the tests. The procedure of making

samples shoul d be studie d separately (refe r to any book o n Soil Testing). Tests o n sand ma y be

conducted either in a saturated state or in a dry state. Slow or consolidated undraine d tests may be

carried out as required.

Drained o r Slow Test s

At least three identical samples havin g the same initial conditions are to be used. For slow test s

under saturated conditions the drainage valve should always be kept open. Each sample should be](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-299-2048.jpg)

![288 Chapte r 8

Any compressio n testin g apparatus wit h arrangement fo r strai n contro l ma y b e use d fo r

testing the samples . The axial load u may be applied mechanically or pneumatically.

Specimens of height to diameter ratio of 2 are normally used for the tests. The sampl e fail s

either by shearing on an inclined plane (if the soil is of brittle type) or by bulging. The vertical stress

at any stage of loading is obtained by dividing the total vertical load by the cross-sectional area. The

cross-sectional are a of the sample increases with the increase in compression. Th e cross-sectiona l

area A at any stage of loading of the sample may be computed on the basic assumption that the total

volume of the sample remains the same. That is

AO/IQ = A h

where A Q, hQ = initial cross-sectional area and height of sample respectively.

A,h = cross-sectional area and height respectively at any stage of loading

If Ah is the compression of the sample, the strain is

A/z

£

~ ~j~~ sinc e A/ z =h

0- h, we may write

AO/ZQ = A(/ZO - A/z )

Therefore, A = -j^-= ^

^ = ^

(8.45 )

The average vertical stress at any stage of loading may be written as

P P(l-e]

A A ()

(8.46)

where P is the vertical load at the strain e.

Using the relationship given by Eq. (8.46) stress-strain curves may be plotted. The peak value

is taken as the unconfined compressiv e strength qti, that is

( f f

i ) f

=

V u (8-47 )

The unconfine d compression test (UC ) i s a specia l cas e o f th e unconsolidated-undrained

(UU) triaxial compression test (TX-AC). The only difference between the UC test and UU test is

that a total confining pressure under which no drainage was permitted was applied in the latter test.

Because of the absence of any confining pressure in the UC test, a premature failure through a weak

zone may terminate an unconfined compression test. For typical soft clays, premature failure is not

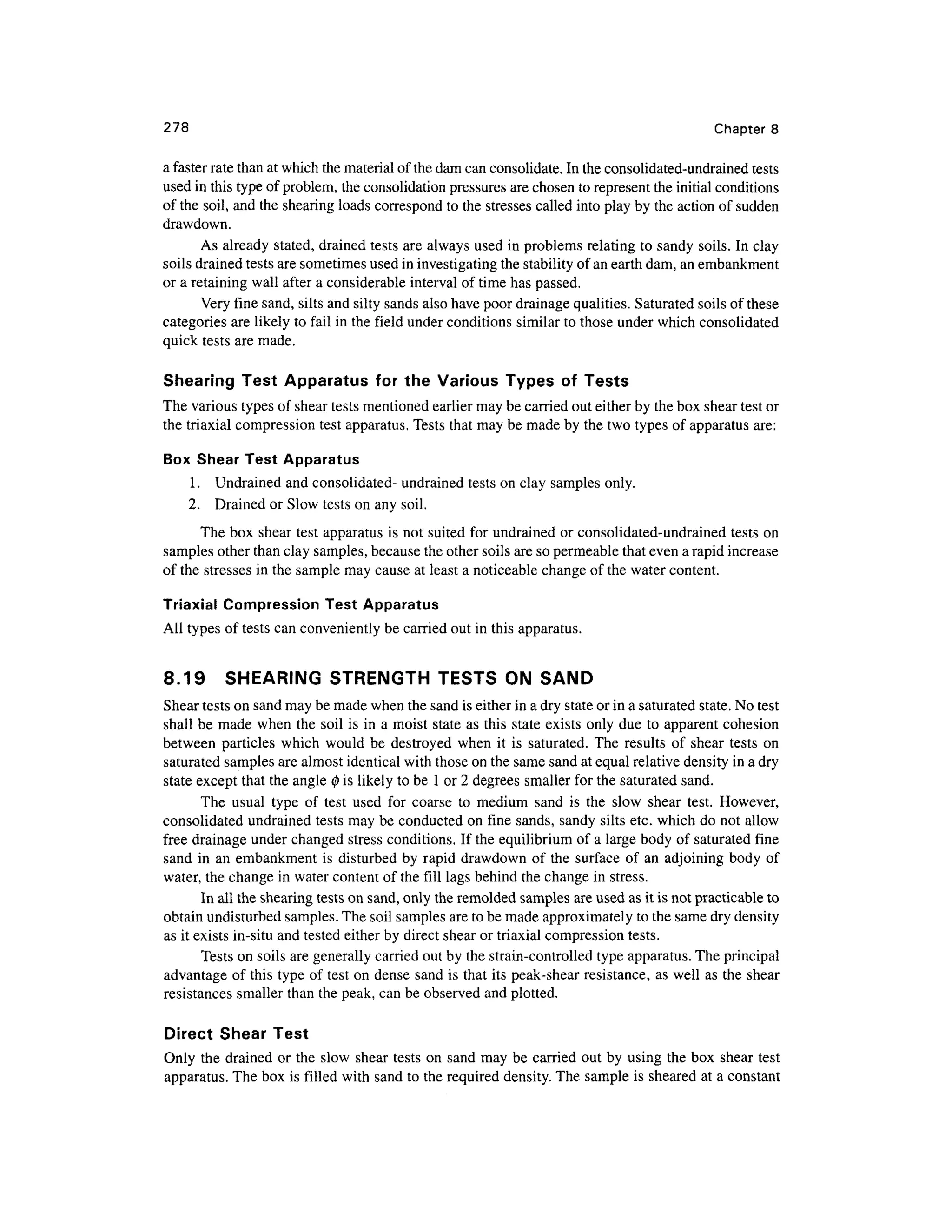

likely to decrease th e undrained shear strength by more than 5%. Fig 8.23 show s a comparison of

undrained shear strength values from unconfine d compression tests and from triaxia l compression

tests on soft-Natsushima cla y from Toky o Bay. The properties o f the soil are :

Natural moisture content w = 80 to 90%

Liquid limit w,= 10 0 to 110 %

Plasticity index /; = 60%

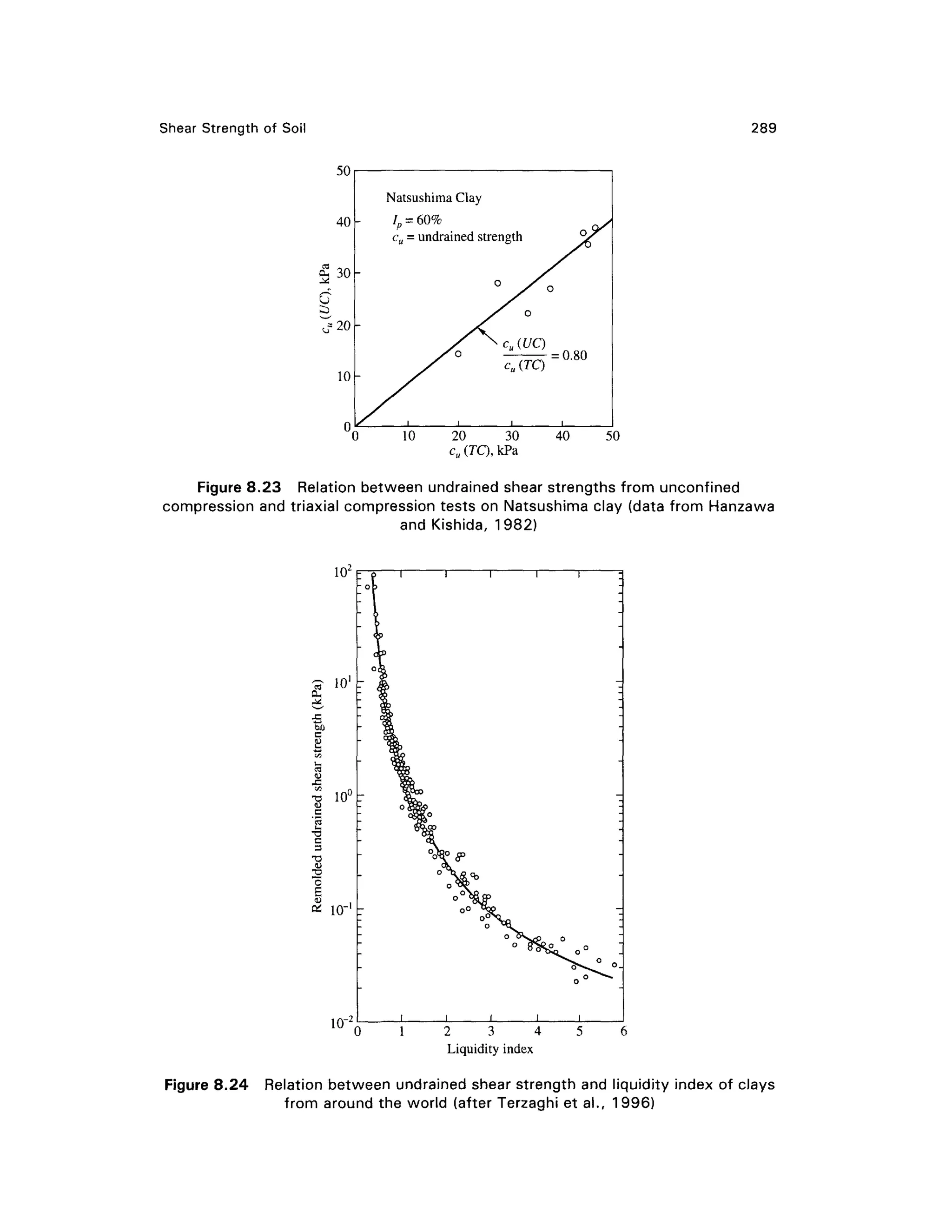

There is a unique relationship between remolded undraine d shear strength and the liquidity

index, / , as shown in Fig. 8.24 (after Terzaghi et al., 1996). This plot includes soft clay soil and silt

deposits obtaine d from differen t part s of the world.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-307-2048.jpg)

![298 Chapter 8

undrained tests on the sam e soils, the volume change is zero and consequently(j) d fo r dense sand s

and heavily overconsolidated clays is greater than 0'. Fig. 8.28(a) shows the nature of variation of

the deviator stres s with axial strain. During the application o f the deviator stress, the volume of the

specimen gradually reduces for normally consolidated clays. However, overconsolidated clays go

through some reduction of volume initially but then expand.

8.24 POR E PRESSURE PARAMETERS UNDER UNDRAINE D

LOADING

Soils in nature are at equilibrium under their overburden pressure. If the same soil is subjected to an

instantaneous additional loading, there will be development of pore pressure if drainage is delayed

under the loading. The magnitude of the pore pressure depends upo n the permeability of the soil,

the manner of application of load, the stress history of the soil, and possibly many other factors. If

a load is applied slowl y and drainage takes place with the application of load, there will practically

be no increase o f pore pressure. However, if the hydraulic conductivity of the soil is quite low, and

if the loading is relatively rapid, there will not be sufficient time for drainage to take place. In such

cases, there will be an increase in the pore pressure in excess of the existing hydrostatic pressure. It

is therefore necessary man y times to determine or estimate the excess pore pressure for the various

types o f loadin g conditions . Por e pressure parameter s ar e use d t o express th e response o f por e

pressure t o changes i n total stres s under undrained conditions. Values of the parameters ma y be

determined i n the laboratory an d can be used t o predict pore pressure s i n the field under similar

stress conditions.

Pore Pressur e Parameter s Under Triaxia l Test Condition s

A typical stress application on a cylindrical element of soil under triaxial test conditions is shown in

Fig. 8.29 (Adj > A<73). AM is the increase in the pore pressure without drainage. From Fig. 8.29, w e

may write

AM3 = 5A<73, Awj = Afi(Acr1 - Acr 3), therefore,

AM = AMj + AM3 = #[A<73 + /4(A(Tj - Acr 3)]

or A M =BAcr3 + A(Aer, - A<r 3)

where, A = AB

for saturate d soils B = 1, so

(8.50)

(8.51)

Aw = A< 7 - A<73)

IACT,

(8.52)

ACT,

A<73 A<7 3

(ACT, - ACT 3)

ACT, AM,

ACT, ACT, (ACT, - ACT 3)

Figure 8.29 Exces s water pressur e unde r triaxia l tes t conditions](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-317-2048.jpg)

![Shear Strengt h of Soi l 30 7

Example 8.15

A normall y consolidate d cla y wa s consolidate d unde r a stres s o f 315 0 lb/ft2

, the n sheare d

undrained in axial compression. The principal stress difference at failure was 2100 lb/ft2

, an d the

induced por e pressur e a t failur e wa s 184 8 lb/ft2

. Determin e (a ) th e Mohr-Coulom b strengt h

parameters, i n term s o f bot h tota l an d effectiv e stresse s analytically , (b ) comput e ((T,/cr 3), and

(<7/

1/cr/

3),, and (c) determine the theoretical angle of the failure plane in the specimen.

Solution

The parameters required are: effective parameters c' and 0', and total parameters c and 0.

(a) Given <T3/= 3150 lb/ft 2

, and (<TJ - a 3)f= 2100 lb/ft2

. The total principal stress at failure alf

is obtained from

fflf= (CT j - aj f+ <7 3/ =2100 + 3150 =5250 lb/ft 2

Effective o /

1/= alf- u f= 5250 - 184 8 = 3402 lb/ft 2

°V =

cr3/- "/= 3150 - 184 8 = 1302 lb/ft2

Now cr j = <7 3 tan2

(45° + 0/2) + 2c tan (45° + 0/2

)

Since the soil is normally consolidated, c = 0. As such

---tan2

(45°

-tan (45 or

T * I * " 1 210

° ' I 2 1 0 0

1, 1 Co

Total 0 =sin ]

-

= sin"1

-

=14.5

5250 +3150 840 0

^ . - i 210 0 . _ ! 2100 _ , _ „

Effective 0 = sin -

= sin -

=26.5

3402+1302 470 4

(b) The stress ratios at failure are

^L=5250 ^[ = 3402 =Z6

1

cr3 315 0<j' 3 130 2

(c) From Eq. (8.18)

a = 45° +—= 45° +—= 58.25°

f

2 2

The above problem can be solved graphically by constructing a Mohr-Coulomb envelope.

Example 8.16

The following results were obtained at failure in a series of consolidated-undrained tests, with pore

pressure measurement, on specimens of saturated clay. Determine the values of the effective stres s

parameters c'and 0x

by drawing Mohr circles.

a3 kN/m2

a , - o 3 kN/m2

u w kN/m2

150 19 2 8 0

300 34 1 15 4

450 50 4 22 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-326-2048.jpg)

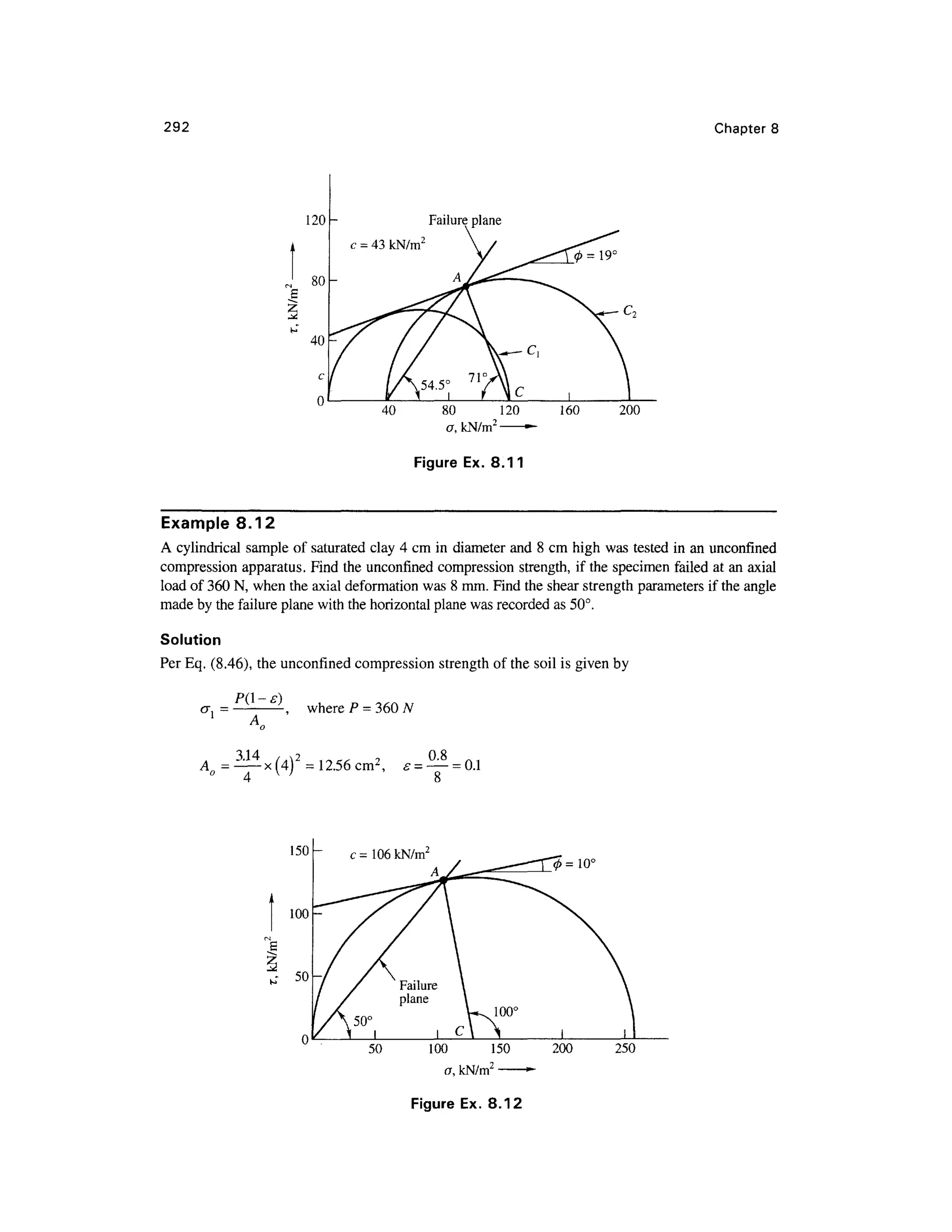

![Shear Strengt h o f Soi l 309

'0 20 0 40 0 60 0 80 0 100 0 120 0

cr, kN/m2

-

Figure Ex. 8.17

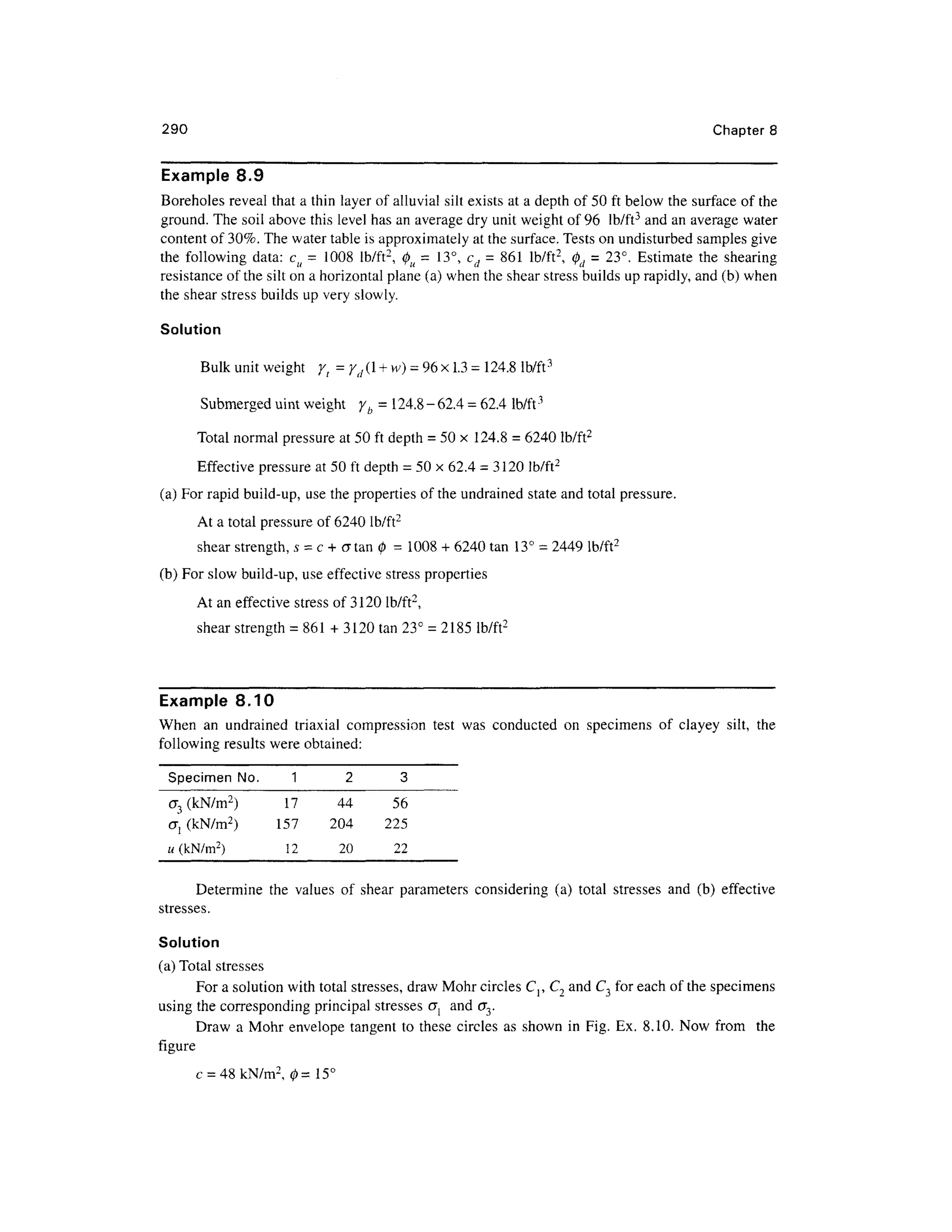

The Mohr circles at failure and the corresponding failure envelopes for both series of tests are

shown in Fig. Ex. 8.17. In both cases the failure envelope is the line nearest to the common tangent

to the Mohr circles. The total stress parameters representing the undrained strength of the clay are:

cu = 85 kN/m2

; 0 u = 0

The effective stres s parameters, representin g the drained strength of the clay, are:

c' = 20 kN/m2

; 0 = 26°

a~ A/7//? n AWV n Are a (corrected ) a, - a- a,

3 0 0 1 3 1

a

b

kN/m2

200

400

600

200

400

600

0.129

0.132

0.135

0.142 0.07 7

0.161 0.09 5

0.186 0.11 0

cm2

13.04

13.09

13.12

12.22

12.25

12.40

kN/m2

170

160

172

382

691

1020

kN/m2

370

564

772

582

1091

1620

Example 8.1 8

An embankmen t is being constructed of soil whose properties ar e c'-107 1 lb/ft 2

, 0' = 21° (all

effective stresses) , an d y= 99.85 lb/ft3

. The pore pressure parameters as determined fro m triaxia l

tests are A = 0.5, and B = 0.9. Find the shear strength of the soil at the base of the embankment just

after th e heigh t o f fil l ha s bee n raise d fro m 1 0 ft t o 2 0 ft . Assume that the dissipatio n of por e

pressure during this stage of construction is negligible, and that the lateral pressure at any point is

one-half of the vertical pressure.

Solution

The equation for pore pressure is [Eq. (8.51)]

A« = 5JAcr3 +A(AcTj -Acr3)|

AcTj = Vertical pressure due to 1 0 ft of fill = 10 x 99.85 = 998.5 lb/ft2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-328-2048.jpg)

![310 Chapter s

9985

ACT, = ^

^ = 499.25 lb/ft 2

3

2

Therefore, A w = 0.9[499.25 + 0.5 x 499.25] = 674 lb/ft 2

Original pressure, ^ = 10x99.85 = 998.5 lb/ft 2

Therefore, a' = <j} + A<JI - A w

= 998.5 + 998.5 -674 = 1323 lb/ft2

Shear strength, s = c' + a'tan0'= 1071 +1323tan21° = 1579 lb/ft 2

Example 8.1

9

At a depth o f 6 m below th e groun d surface a t a site , a van e shea r tes t gav e a torque valu e of

6040 N-cm. The vane was 10 cm high and 7 cm across the blades. Estimate the shear strength of the

soil.

Solution

Per Eq. (8.53)

Torque (r )

c =

where T = 6040 N-cm, L = 10 cm, r = 3.5 cm.

substituting,

6040 , „ X T , 7

c, =

= 6.4 N /cm2

- 6 4 kN/m2

" 2 x3.14 x 3.52

(10 +0.67 x 3.5) ~ °4 K1N/m

Example 8.20

A van e 11.2 5 c m long , an d 7. 5 c m i n diamete r wa s presse d int o sof t cla y a t th e botto m o f a

borehole. Torqu e was applied to cause failure of soil. The shear strength of clay was found t o be

37 kN/m2

. Determine the torque that was applied.

Solution

From Eq. (8.53) ,

Torque, T = cu [2nr2

(L + 0.67r)] wher e c u = 37 kN/m2

= 3.7 N/cm2

- 3.7 [2 x3.14 x (3.75)2

(11.25 + 0.67 x 3.75)] = 4500 N -cm

8.28 GENERA L COMMENT S

One o f the mos t importan t and the mos t controversial engineerin g propertie s o f soi l i s its shea r

strength. The behavior of soil under external load depends on many factors such as arrangement of

particles i n the soi l mass , it s mineralogical composition , wate r content, stres s histor y and many

others. The types of laboratory tests to be performed on a soil sample depends upon the type of soil](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-329-2048.jpg)

![362

9.17 PROBLEM S

Chapter 9

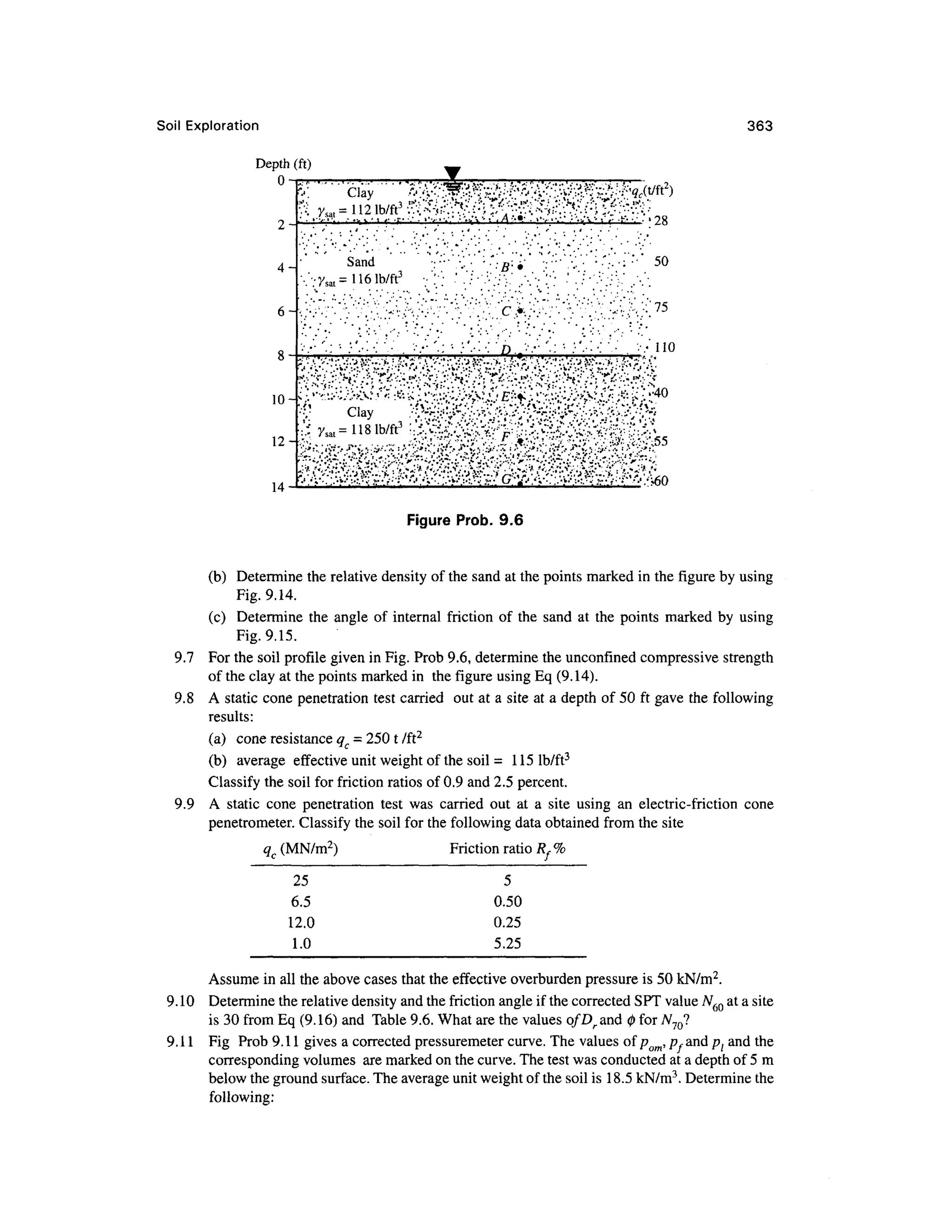

9.1 Comput e the area ratio of a sampling tube given the outside diameter = 100 mm and inside

diameter = 94 mm. In what types of soil can this tube be used for sampling?

9.2 A standar d penetratio n tes t wa s carrie d ou t a t a site . Th e soi l profil e i s give n i n

Fig. Prob. 9.2 with th e penetration values. The average soi l data are given for each layer.

Compute the corrected value s of N and plot showing the

(a) variatio n of observed value s with depth

(b) variatio n of corrected value s with depth for standard energy 60 %

Assume: Eh = 0.7, C d = 0.9, C s = 0.85 an d Cb = 1.05

Depth (m)

0

2m

2-

Sand

•ysdt=185kN/m

3

•

4m

Figure Prob. 9. 2

N-values

20

A

8-

10-

1 9

14

'V ' . '. ' ' ' '

''-;'.- • ''• ;B ;• ''•:

'"' •"•' 'V - ?•'"••..'• ''".' i .'"•'•'-.v' : V

-'':

'..'' •'•'.' i .'"•''•'•.'J'' J

v•"• • : 'j.(- /•- .'.*•> * . ,v - V : 'i.^; .V

:

*y ... v - V ;'*; •

.7 ^y at = is 5 kN/m3

J'V'c ,•*'.;--•'•/-.- .'/"j;":^

Sand• -.;• • ••'.. :. ; ' . '.-.•' • ' . ; • . '

. :y sal= 1981kN/m3

:/ * . . •.,.'- . - :-.-'?. ,

. . C . . - . . . - ; • • - • • • '

,"

m

t-

m

m

[.'•'

. 3 0

' f " ^ *

/ /^ ]

CV

1 5

^ /''A/- ' 19

•

9.3 Fo r the soil profile given in Fig. Prob 9.2, compute the corrected values of W for standar d

energy 70% .

9.4 Fo r the soil profile given in Fig. Prob 9.2, estimate the average angle of friction for the sand

layers based o n the following:

(a) Tabl e 9.3

(b) E q (9.8 ) by assuming the profile contains less tha n 5% fines (Dr ma y b e taken fro m

Table 9.3 )

Estimate the values of 0 and Dr for 60 percent standar d energy.

Assume: Ncor = N6Q.

9.5 Fo r the corrected value s of W 60 given in Prob 9.2, determine the unconfined compressiv e

strengths o f cla y a t point s C an d D i n Fi g Pro b 9. 2 b y makin g us e o f Tabl e 9. 4 an d

Eq. (9.9). What is the consistency of the clay?

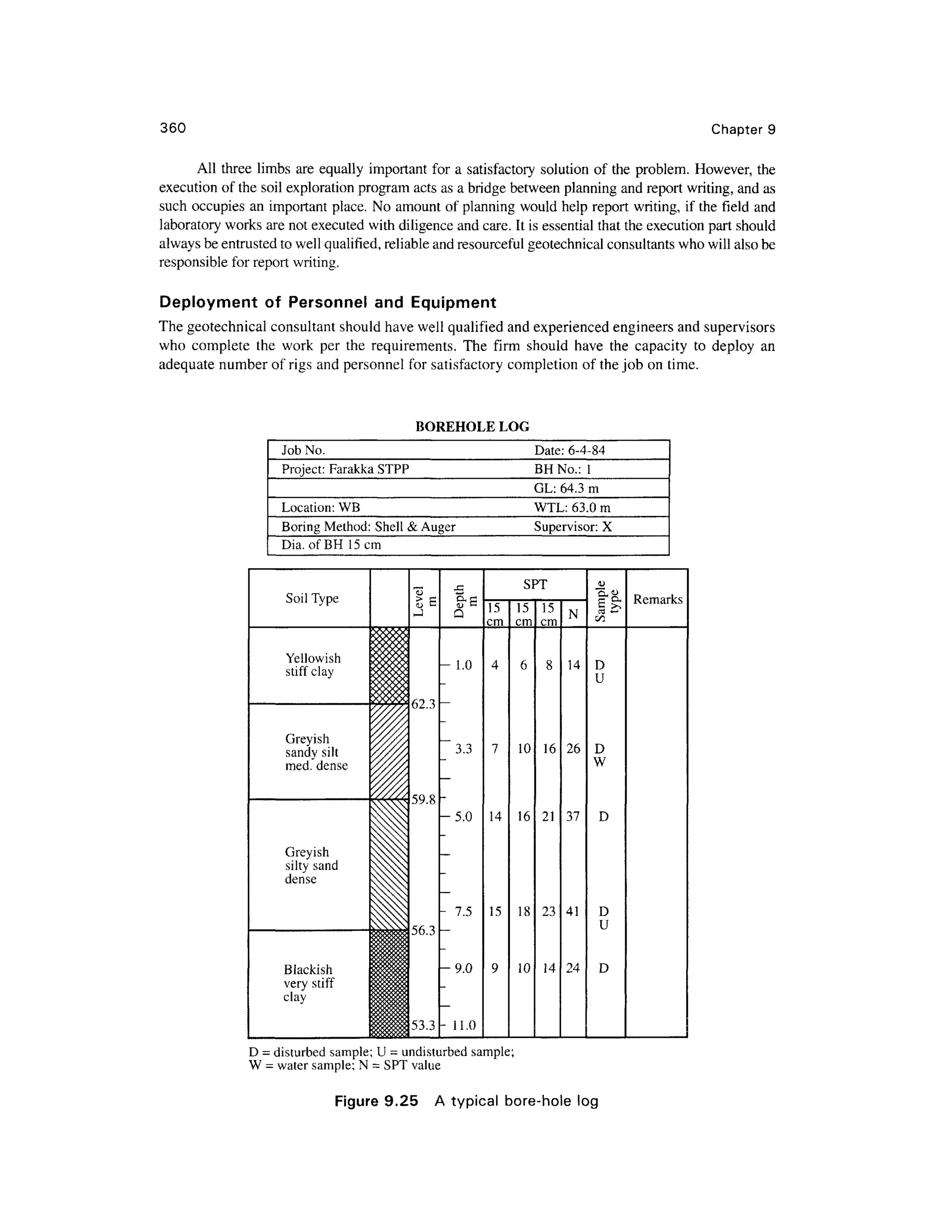

9.6 A stati c con e penetratio n tes t wa s carrie d ou t a t a sit e usin g a n electric-frictio n con e

penetrometer. Fig . Pro b 9. 6 give s th e soi l profil e an d value s o f q c obtained a t variou s

depths.

(a) Plo t the variation of q wit h depth](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-381-2048.jpg)

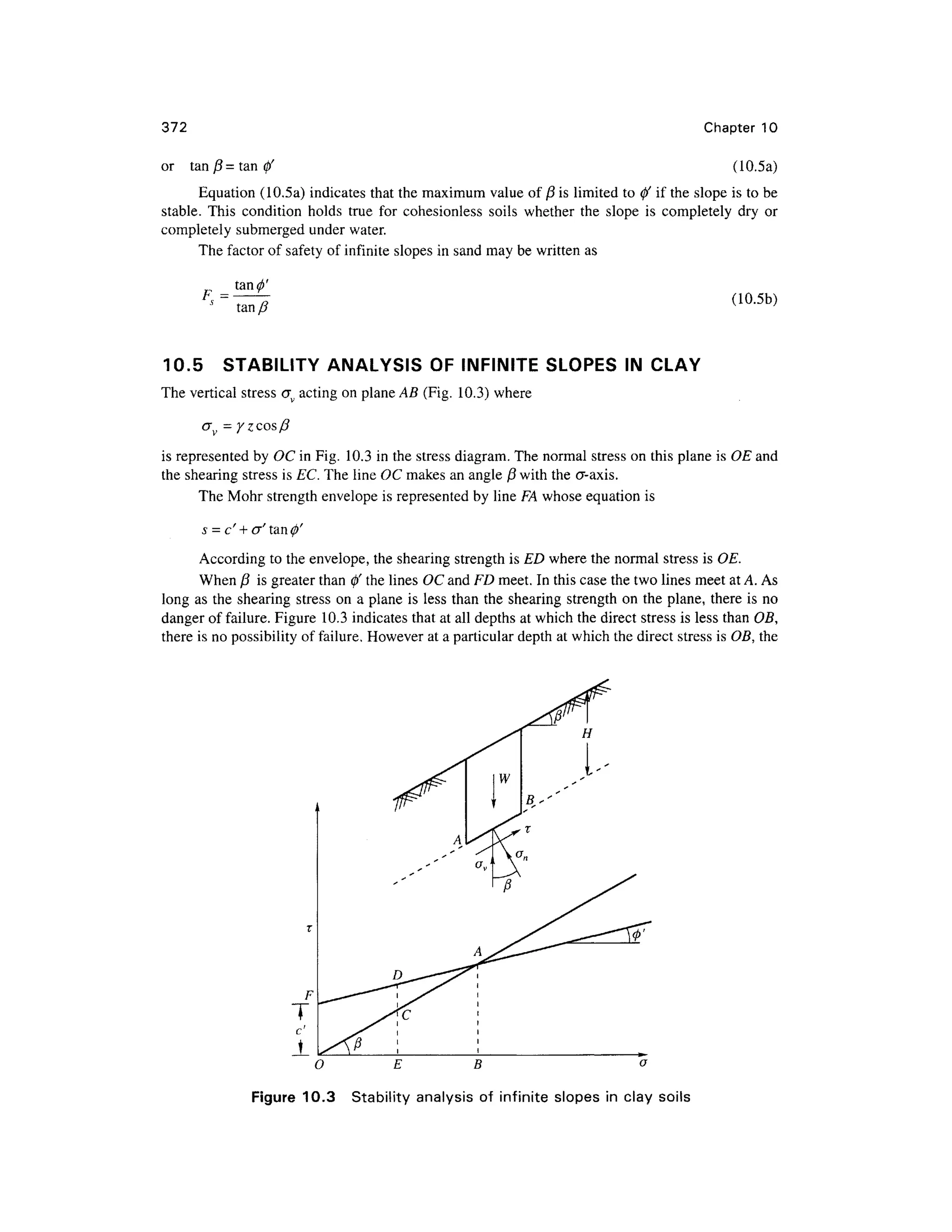

![Stability of Slope s 37 3

shearing strength and shearing stres s value s are equal as represented b y AB, failur e i s imminent.

This depth at which the shearing stress and shearing strength are equal is called the critical depth.

At depths greater than this critical value, Fig. 10.3 indicates that the shearing stress is greater than

the shearing strength but this is not possible. Therefore it may be concluded that the slope may be

steeper tha n 0' as long as the depth of the slope is less than the critical depth.

Expression for th e Stabilit y of a n Infinite Slop e o f Cla y o f Dept h H

Equation (10.2) gives the developed shearin g stress as

T = c'm+(T'tan</>'m (10.6 )

Under conditions o f no seepage an d no pore pressure, the stress component s o n a plane at

depth H and parallel to the surface of the slope are

r=

<j' = yHcos 2

j3

Substituting these stress expressions i n the equation above and simplifying, we have

c'm = YHcos2

0 (tan 0 -tan 0'

J

c'

or N = ^

- = cos2

/?(tanytf-tan^) (10.7 )

yti

where H i s th e allowabl e heigh t an d th e ter m c'Jy H i s a dimensionless expressio n calle d th e

stability number and is designated a s A^. This dimensionless number is proportional to the required

cohesion and is inversely proportional to the allowable height. The solution is for the case when no

seepage is occurring. If in Eq. (10.7) the factor of safety with respect to friction is unity, the stability

number with respect t o cohesion ma y be written as

8)

, c

where c m= —

The stability number in Eq. (10.8) may be written as

where Hc = critical height. From Eq. (10.9), we have

Eq. (10.10) indicates that the factor of safety with respect to cohesion, Fc, is the same as the

factor of safety with respect t o height F H.

If there i s seepage parallel t o the ground surfac e throughout the entire mass , wit h the fre e

water surface coinciding with the ground surface, the components o f effective stresses o n planes

parallel to the surface of slopes at depth H are given as [Fig. 10.4(a)].

Normal stres s

(lO.lla)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/geotechbook-240326034957-6522ccd8/75/geotech-book-FOR-CIVIL-ENGINEERINGGG-pdf-392-2048.jpg)

![Stability of Slope s 37 5

Example 10. 3

Find the factor of safety of a slope of infinite extent having a slope angle = 25°. The slope is made

of cohesionless soi l with 0 = 30°.

Solution

Factor o f safety

tan 30° 0.577 4

tan/? ta n 25° 0.466 3

Example 10. 4

Analyze the slope of Example 10. 3 if it is made of clay having c' - 3 0 kN/m2

, 0' =20°, e = 0.65 and

Gs = 2.7 and under the following conditions: (i) when the soil is dry, (ii) when water seeps parallel

to the surface of the slope, and (iii) when the slope is submerged.

Solution

For e = 0.65 and G = 2.7

= 27x^1 =

= (2. 7 +0.65)x9.81 =

ld

1 + 0.65 /sa t

1 +0.65

yb = 10.09 kN/m 3

(i) For dry soil the stability number Ns i s

c

N = ——— = cos2

/?(tan/?- tan<j>') whe n F,=l

' d c

= (cos 25° )2

(tan 25° -ta n 20°) = 0.084.

c' 3 0

Therefore, th e critical height H = -

= -

=22.25 m

16.05x0.084

(ii) For seepage parallel to the surface of the slope [Eq . (10.13)]

c' 100 Q

N = — -—= cos2

25° ta n 25°-^--

- tan 20° = 0.231 5

s

y tHc 19. 9

Hc=^= 3

°

= 6.5 1 m

c

y tNs 19.9x0.231 5

(iii) Fo r the submerged slope [Eq . (10.14)]

N = cos2

25° (tan 25° - ta n 20°) = 0.084

c