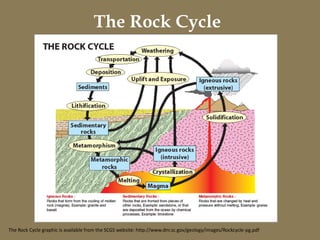

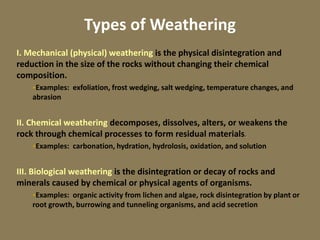

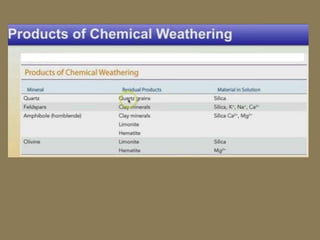

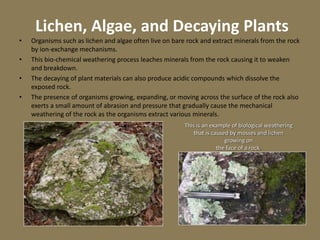

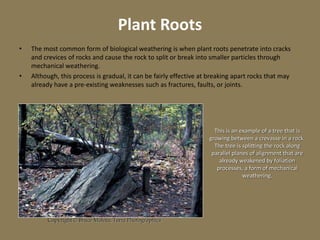

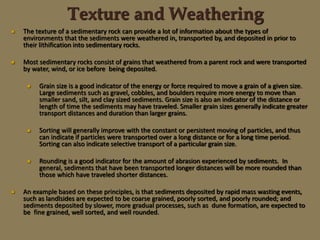

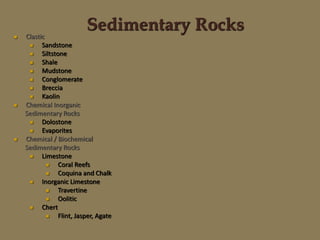

The document discusses the three major rock types - igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic - and how they form. It also describes the rock cycle and the processes of weathering, erosion, and deposition that transform rocks over time. Weathering breaks rocks down through mechanical, chemical and biological processes. Erosion then transports the weathered materials which may be deposited and lithified into sedimentary rocks, starting the cycle again.