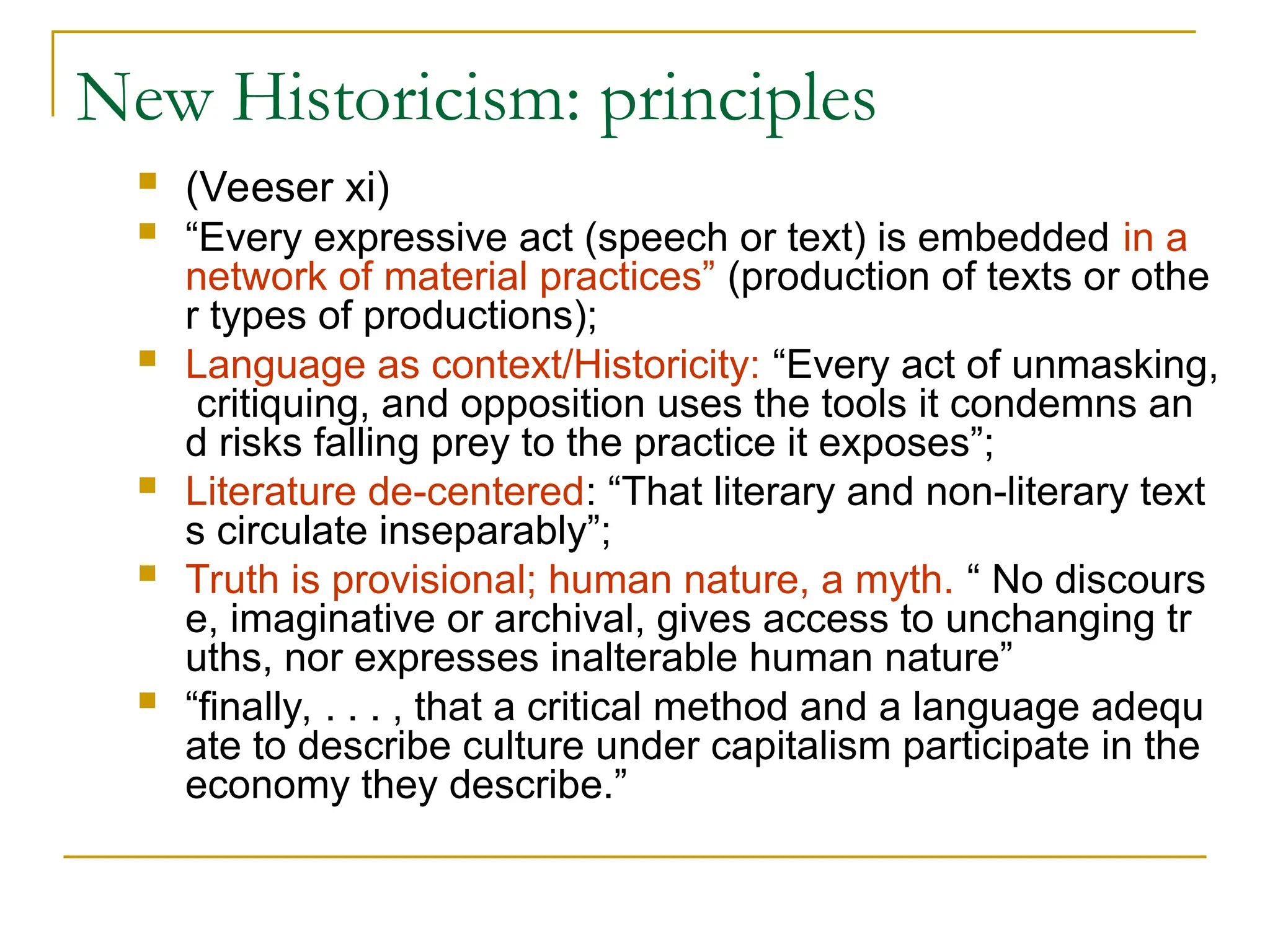

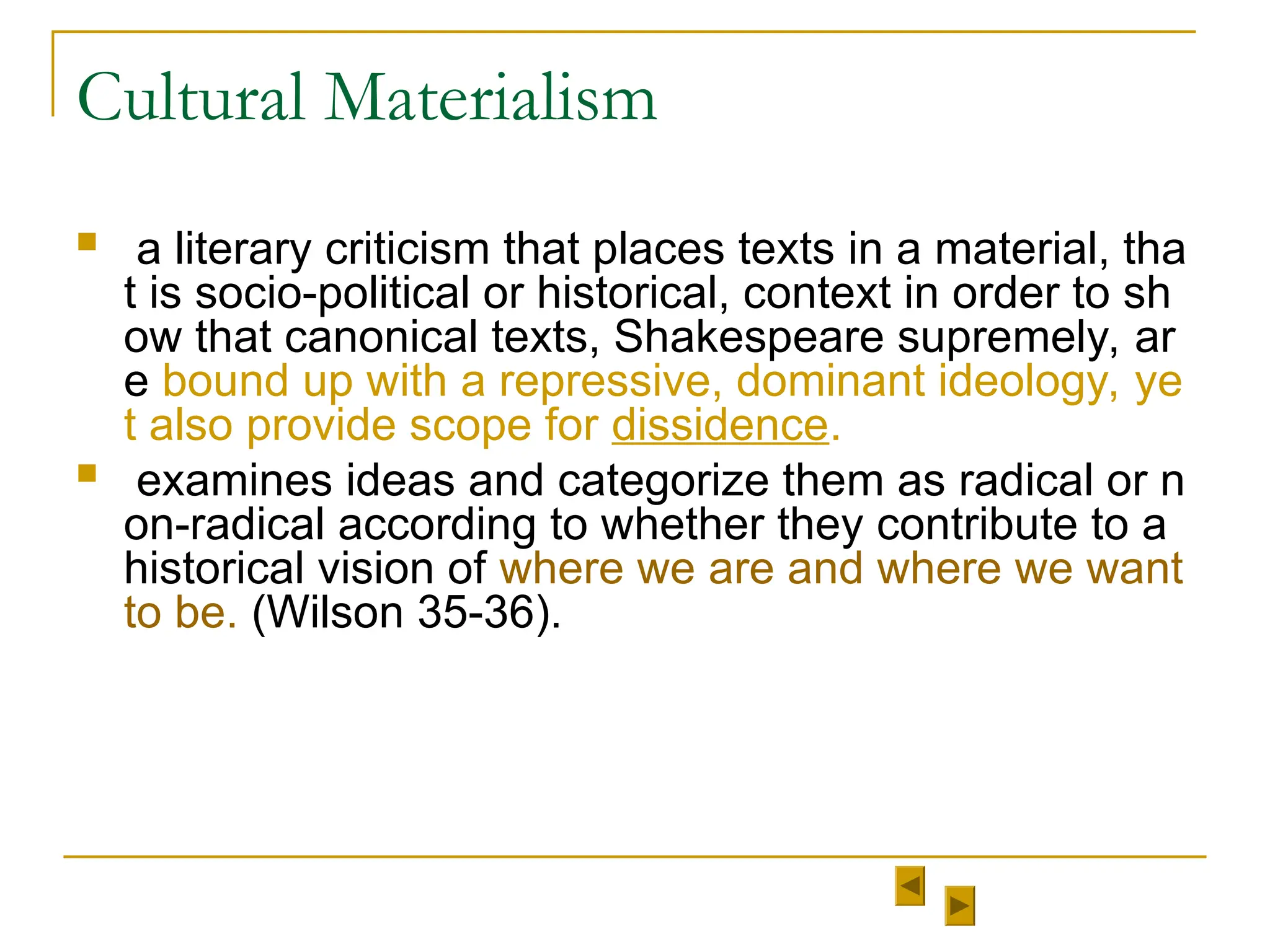

The document outlines the theoretical frameworks of new historicism and cultural materialism, highlighting the influence of Foucault on the understanding of history and discourse. It emphasizes that history is not a coherent narrative but is shaped by social practices and material conditions, incorporating examples from literary texts like Shakespeare's works to illustrate these concepts. The discussion also critiques the limitations of traditional historicism and new criticism, advocating for a more nuanced interpretation of literature within its sociopolitical context.