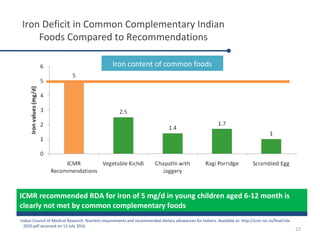

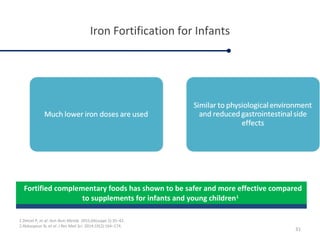

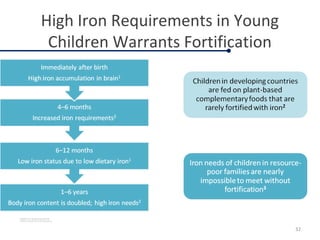

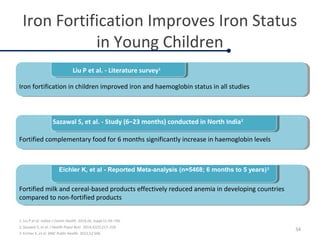

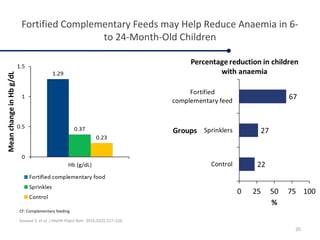

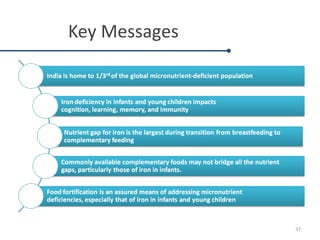

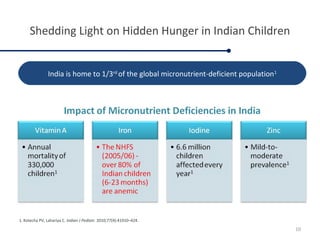

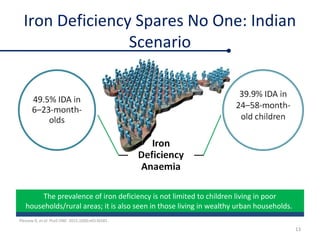

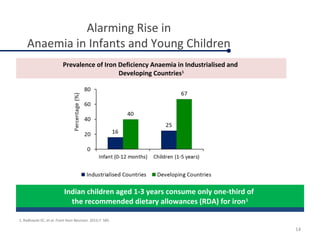

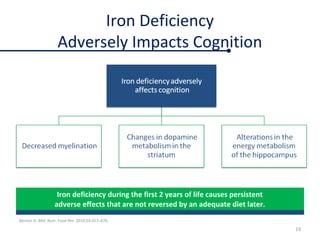

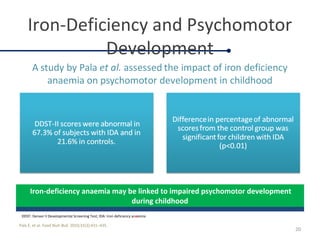

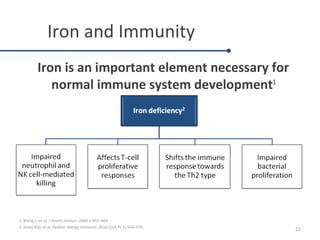

Fortified complementary foods can help address hidden hunger and nutrient deficiencies in children under 2 years of age. Iron deficiency is a particular problem, with prevalence of anemia estimated to affect over 50% of Indian children. While breastmilk is important, it does not provide all nutrients needed during complementary feeding. Common local foods are also low in critical nutrients like iron. Fortifying complementary foods with micronutrients is a promising strategy, as it has been shown in multiple studies to improve iron and hemoglobin status in young children. Fortification may help bridge the nutrient gaps more effectively than oral supplements alone. Widespread use of fortified complementary foods has the potential to reduce anemia and its cognitive impacts on young, developing children.

![Complementary Feeding: A Critical

Window for Improving Iron Status

Krebs N, et al. Nutr Today. 2014;49(6):271–277. 24

1000 days critical window

PREGNANCY Exclusive

Breast Feeding

COMPLEMENTARY FEEDING OUTCOMES

↓ Iron stores

↑ Postnatal requirement

Low Fe intake from milk

↓ Milk [Zn] & ↓ Zn intake

Growth requirement

Human Milk

Dependence on CF:

Fe & Zn Rich Foods

(meats) &/or

Fortified Foods

Improved Fe

& Zn Status

Improved Neuro

cognitive Development

& Immune Function

↑LAZ

↑↓ Stunting

↑ Maternal growth & nutritional status

↑ Maternal Education

↓ Enteric infection & inflammation

+

+

CF: Complementary foods; LAZ: Length-for-age Z score; Fe: iron; Zn: zinc .

After 6 months](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fortifiedcomplementaryfoods-170526131116/85/Fortified-complementary-foods-Dr-M-Sucindar-24-320.jpg)

![Nutrient Gap for Iron is the widest

World Health Organization. Complementary feeding: Report of the global consultation [Internet]. 2001.

25

94% of Iron

Requirements

Need to be

Fulfilled by

Complementar

y foods

Nutrient Gaps to be filled by complementary foods

for a breastfed child 12–23 months](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fortifiedcomplementaryfoods-170526131116/85/Fortified-complementary-foods-Dr-M-Sucindar-25-320.jpg)