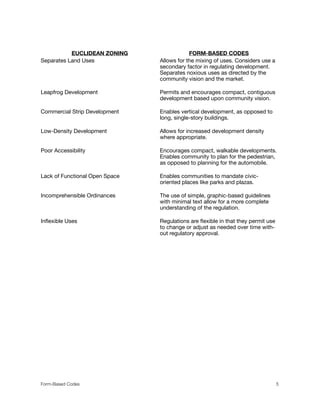

The document discusses form-based codes as an alternative to traditional Euclidean zoning. It provides an overview of form-based codes, including their focus on physical design rather than use. The document then examines a case study of form-based codes being implemented in the Columbia Pike Special Revitalization District in Arlington County, Virginia. Key aspects of the Columbia Pike form-based code included a regulating plan that specified building locations and forms, as well as some optional architectural standards. The effects were quicker approval times for developers and incentives to encourage development that met the community's vision.

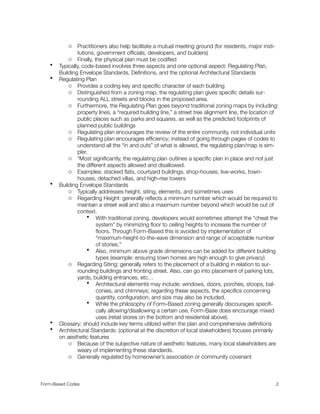

![II. Building Envelope Standards

a. General Principles

i. Buildings are aligned and close to the street with active fronts.

ii. Uniformity creates public space and community identity.

iii. Property lines are physically defined by buildings or street walls.

iv. Buildings are designed for city setting, not suburban areas. The build-

ings should face the general public area, not necessarily towards neigh-

bors.

v. Service areas should be kept away from the street face.

vi. Retail on the ground floor is greatly encouraged in order to keep the

area interesting and open to the public.

vii. Encourage on street parking.

viii. Parking lots should corroborate into shared parking.

b. Building Standards

i. Measure building heights by story.

1. Measuring by just height leads to manipulation of floor heights

by developer.

2. Each building should be between 3-6 stories.

ii. The ground floor should be at least 15 feet tall (measuring floor to ceil-

ing).

iii. All stories above the ground level should be no taller than 14 feet. The

uppermost story should be at least 10 feet tall.

iv. Aside from specially approved balconies, bay windows, stoops and

shop fronts, the Required Building Line is not to be encroached.

c. Ground story façade shall have between 60% and 90% fenestration [an open-

ing in the building wall allowing light and views between interior and exterior.

FENESTRATION is measured as glass area (excluding window frame elements

with a dimension greater than 1 inch for conditioned space and as open area

for parking structures or other un-conditioned, enclosed space)].

d. Upper story facades shall have between 30% and 70% FENSTRATION.

e. Ground stories should be used for retail; entry doors should be spaced out no

greater than 60 feet within any site.

f. Retail should not be located on any floors beyond the ground floor. Allowed

uses for upper floors are restaurants and business professional offices.

Form-Based Codes

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/302326c1-8a84-42b0-858d-78361381a07d-150623141635-lva1-app6892/85/Form-Based-Design-Ord-14-320.jpg)