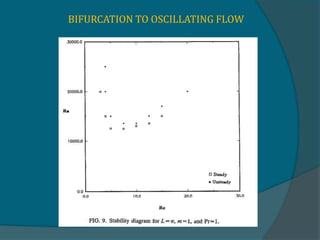

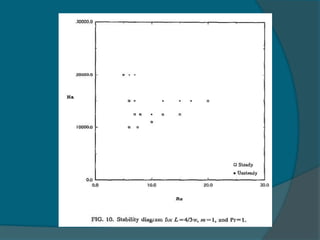

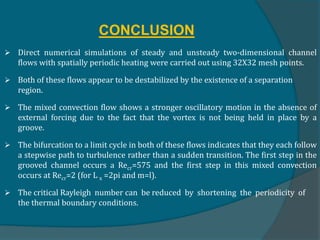

Two-dimensional numerical simulations were conducted of flow through a channel with spatially periodic temperature boundary conditions on the lower wall. The simulations showed:

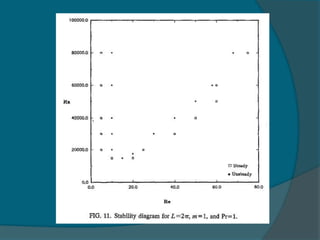

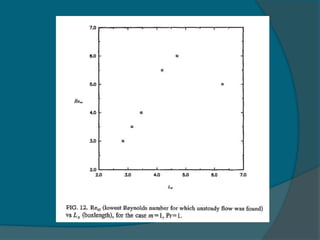

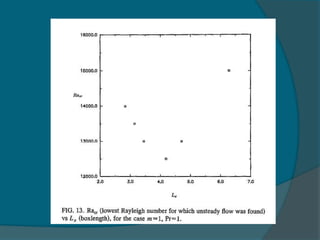

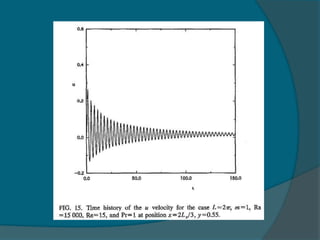

1) A bifurcation to oscillatory flow occurs at Reynolds numbers as low as 4 and Rayleigh numbers as low as 14,500.

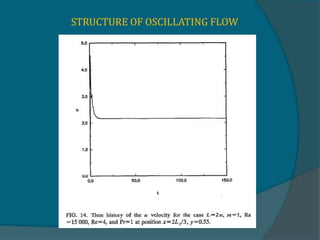

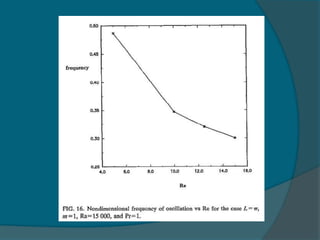

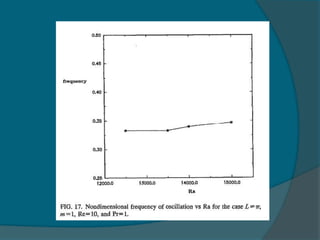

2) The frequency of oscillation decreases with increasing Reynolds number and is independent of the Rayleigh number.

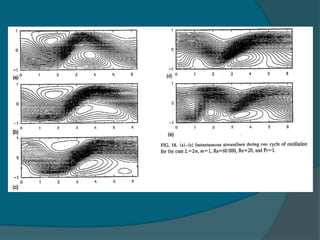

3) Maps were created showing different flow regimes for varying periodicities of the temperature boundary conditions.

![INTRODUCTION

The destabilization of low speed channel flows has attracted attention recently. There

has been particular interest in the structures of the resulting unsteady flows and the

mechanism by which the instability occurs. Applications of these instabilities include

the cooling of electronic equipment and computer circuits [1]. Recent work has

emphasized the prediction and analysis of the frequency behavior of unstable flows.

One particularly successful means of destabilizing a channel flow is the placement of a

groove along one of the walls, perpendicular to the direction of flow. Ghaddar et al. [2],

[3] carried out numerical simulations of a two-dimensional grooved channel flow. They

found that the flow begins to oscillate at a critical Reynolds number of Re=975 for the

geometry studied.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/flowregimesintwo-dimensionalmixed-221215090222-c3b0376e/85/Flow-regimes-in-two-dimensional-mixed-pptx-7-320.jpg)

![Cheng et al.[4] carried out numerical calculations on steady mixed convection in the

entry region of a rectangular duct with a uniform wall flux on all sides. The buoyancy

was found to shorten the entry region, due to the secondary motion carrying hot fluid

away from the walls.

Ostrach and Kamotani [5] carried out experiments on mixed convection with uniform

heating on the lower surface. It was observed that for Ra<8000 and l0<Re<100 steady

vortex rolls aligned to the flow direction are the dominant structure. For Ra>8000 this

structure was found to be unstable and an unsteady and irregular flow appeared.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/flowregimesintwo-dimensionalmixed-221215090222-c3b0376e/85/Flow-regimes-in-two-dimensional-mixed-pptx-8-320.jpg)

![Natural convection in a fluid layer uniformly heated from below will generally be three

dimensional. Busse and Clever[6] investigated the transition from two to three-

dimensional convection over a range of Prandtl numbers 0.01 to 100. They showed

that, for a wave number of , and Prandtl numbers close to 1, two-dimensional

convection can only exist over a very small range of Rayleigh numbers.

Kennedy and Zebib[7] carried out two-dimensional steady numerical calculations of

mixed convection with localized heating on the lower and upper surfaces. The resulting

flow separates just downstream of the heat source so that the vortex roll is now cross

stream and it can be expected that this flow to become unstable with sufficiently larger

driving forces.

3.14

](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/flowregimesintwo-dimensionalmixed-221215090222-c3b0376e/85/Flow-regimes-in-two-dimensional-mixed-pptx-9-320.jpg)

![Unsteady two-dimensional numerical simulations of mixed convection with spatially

periodic heating have been carried out by Wang et al.[8] and Tangborn[9]. Wang et al.

found a region in (Re, Ra) space where the flow is unsteady and extends as low as

Re=2.0. Tangborn showed that if the upper wall is insulated, the flow is stabilized and

will not become unsteady unless the Reynolds number is raised to Re=100. These

results show that this flow becomes unsteady when there is a balance between

buoyancy and pressure forces.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/flowregimesintwo-dimensionalmixed-221215090222-c3b0376e/85/Flow-regimes-in-two-dimensional-mixed-pptx-10-320.jpg)

![NUMERICAL METHOD

The numerical procedure employed here is essentially the same as the technique

used by Kim et al [13]. The curl of the momentum equations is taken so as to remove

pressure as a boundary condition.

A coupled system of three (including the energy equation) second-order equations

is expanded by Fourier series in x and is solved by the Chebyshev-tau method.

Time stepping is Crank-Nicolson for the viscous (linear) terms and Adams-Bashforth

for the convective (nonlinear) terms.

The 32X32 (x and y directions), two-dimensional mesh is used for most of the

simulations.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/flowregimesintwo-dimensionalmixed-221215090222-c3b0376e/85/Flow-regimes-in-two-dimensional-mixed-pptx-16-320.jpg)