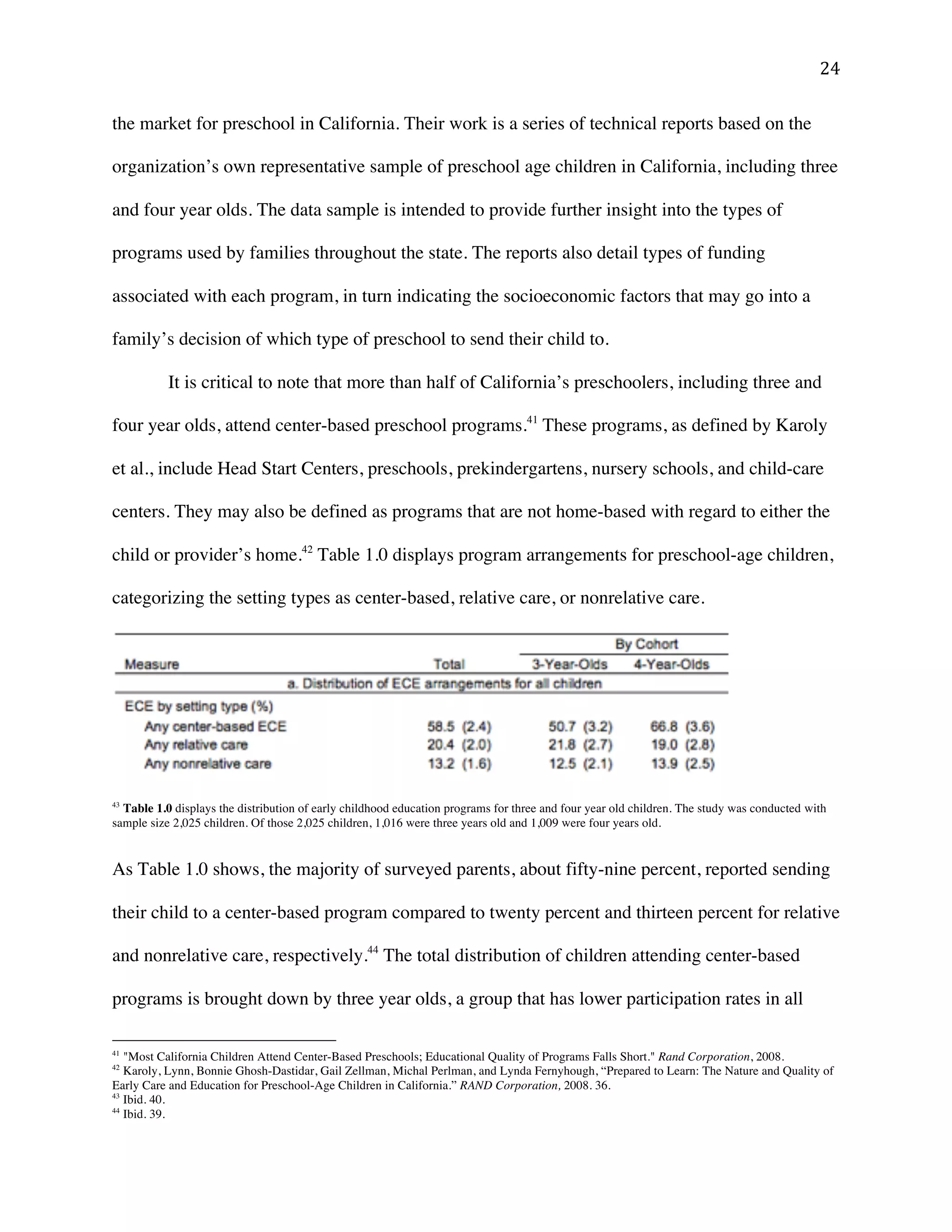

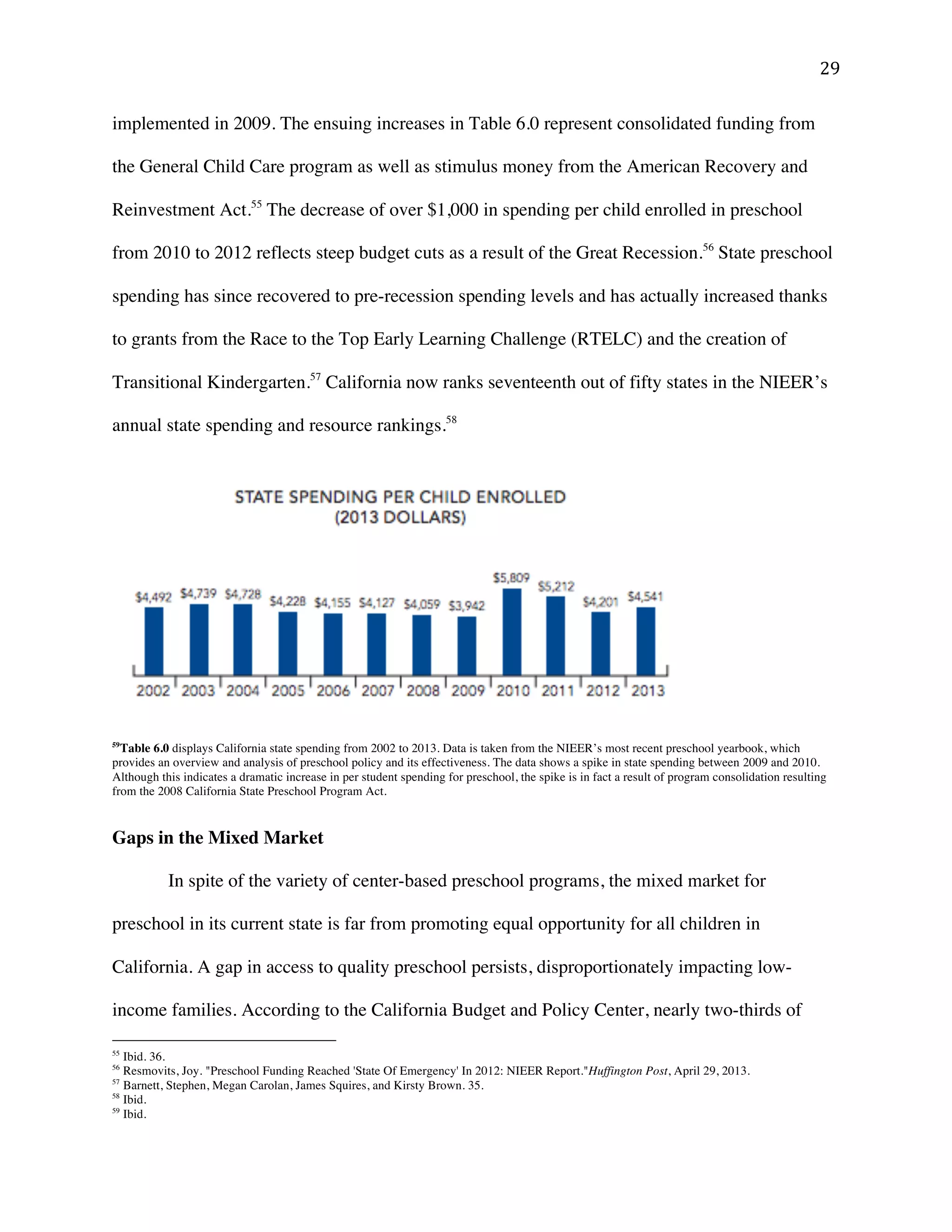

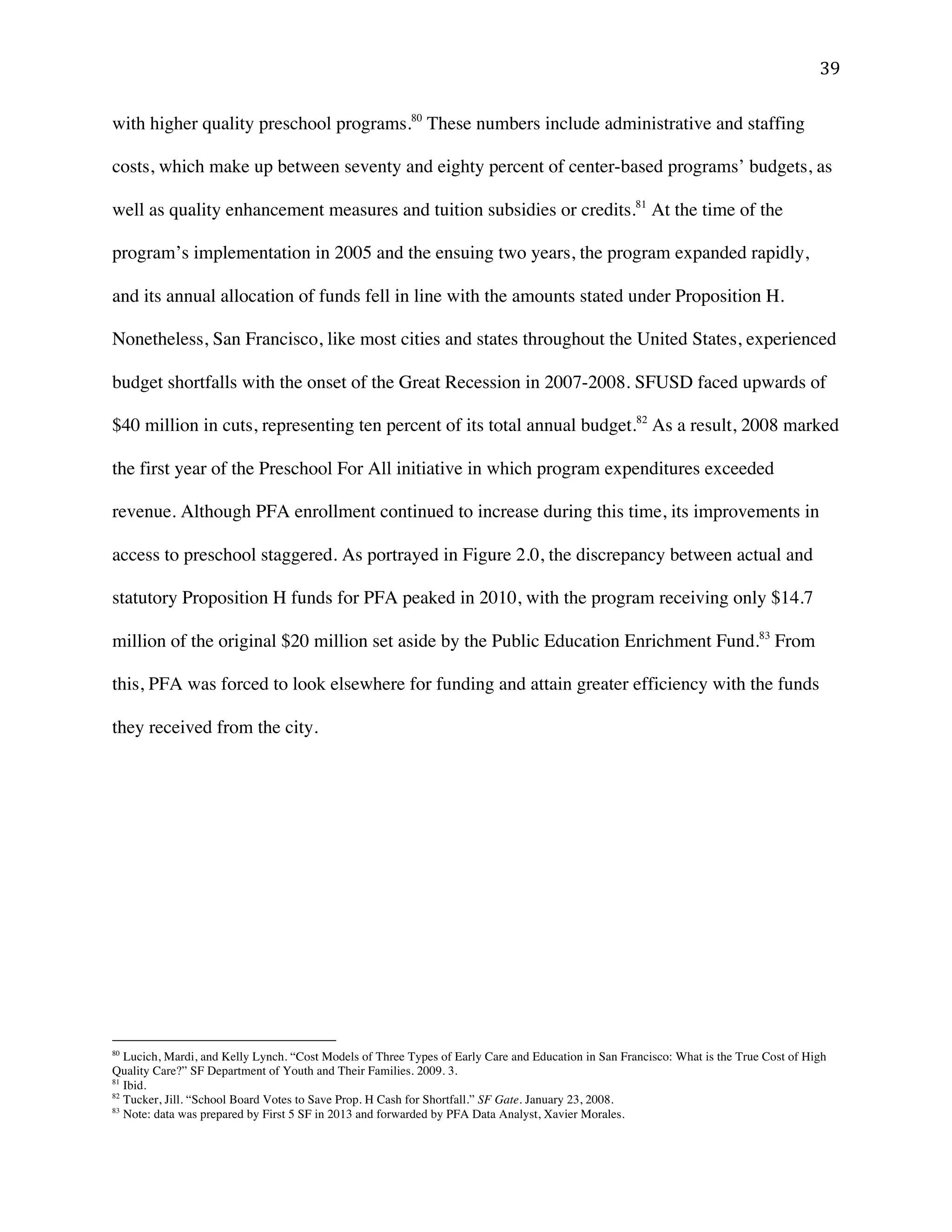

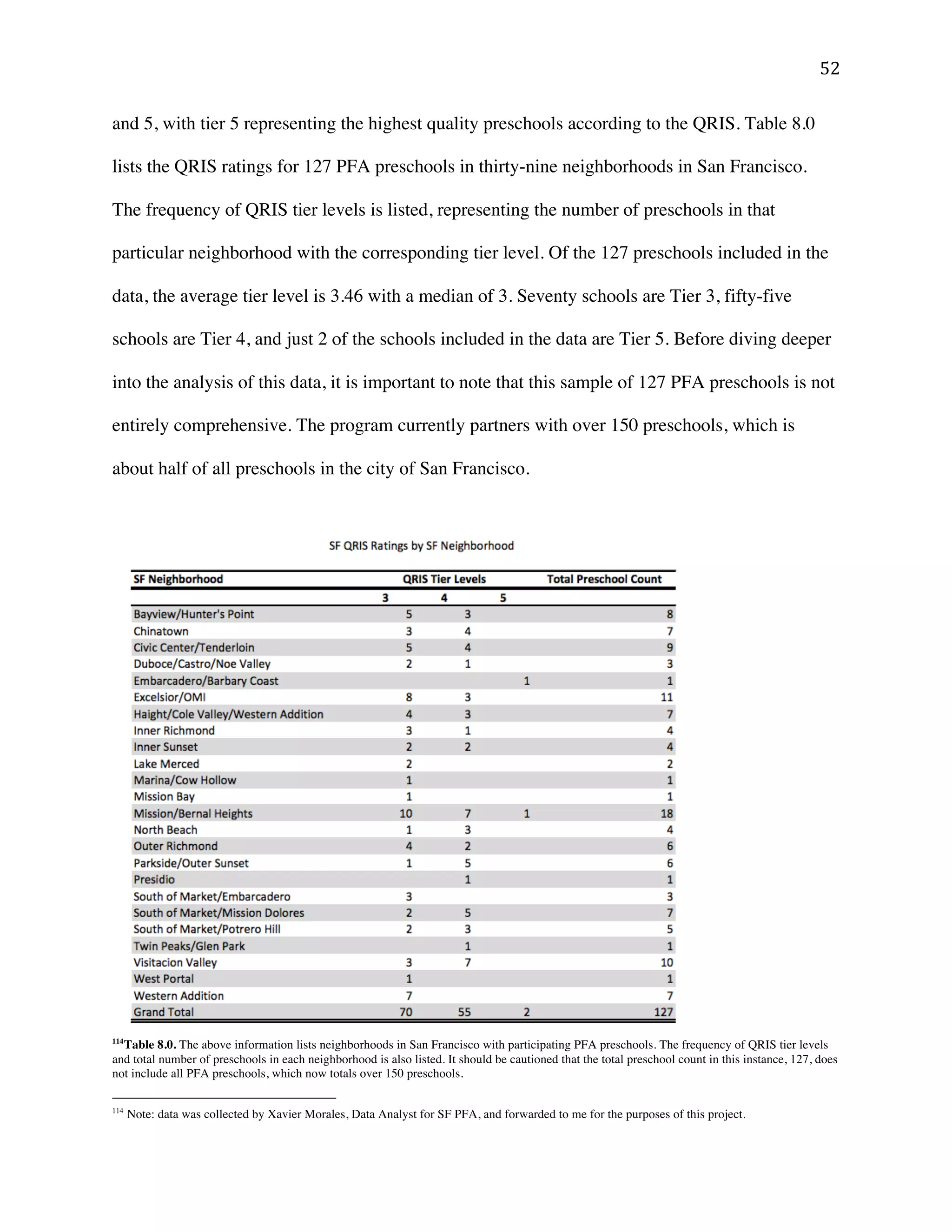

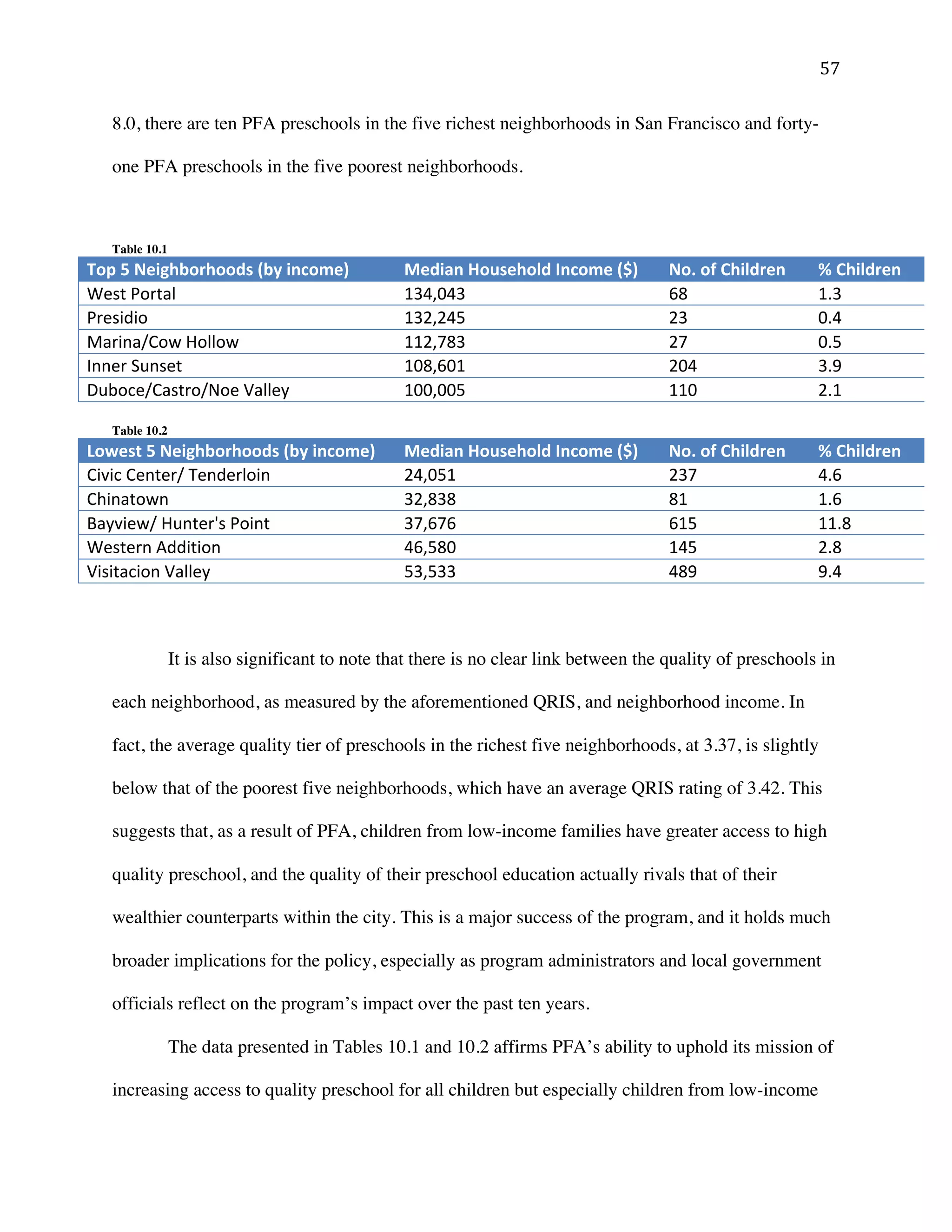

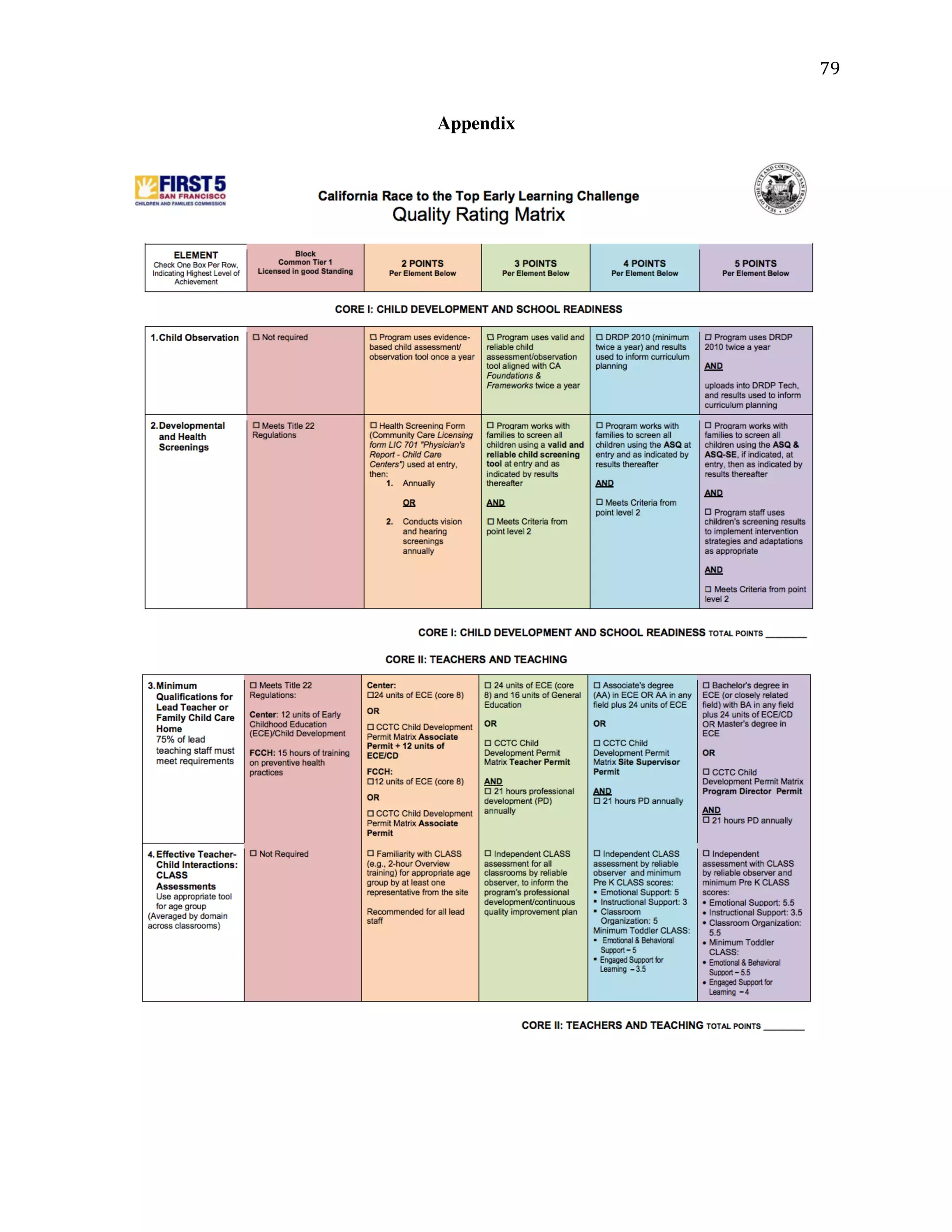

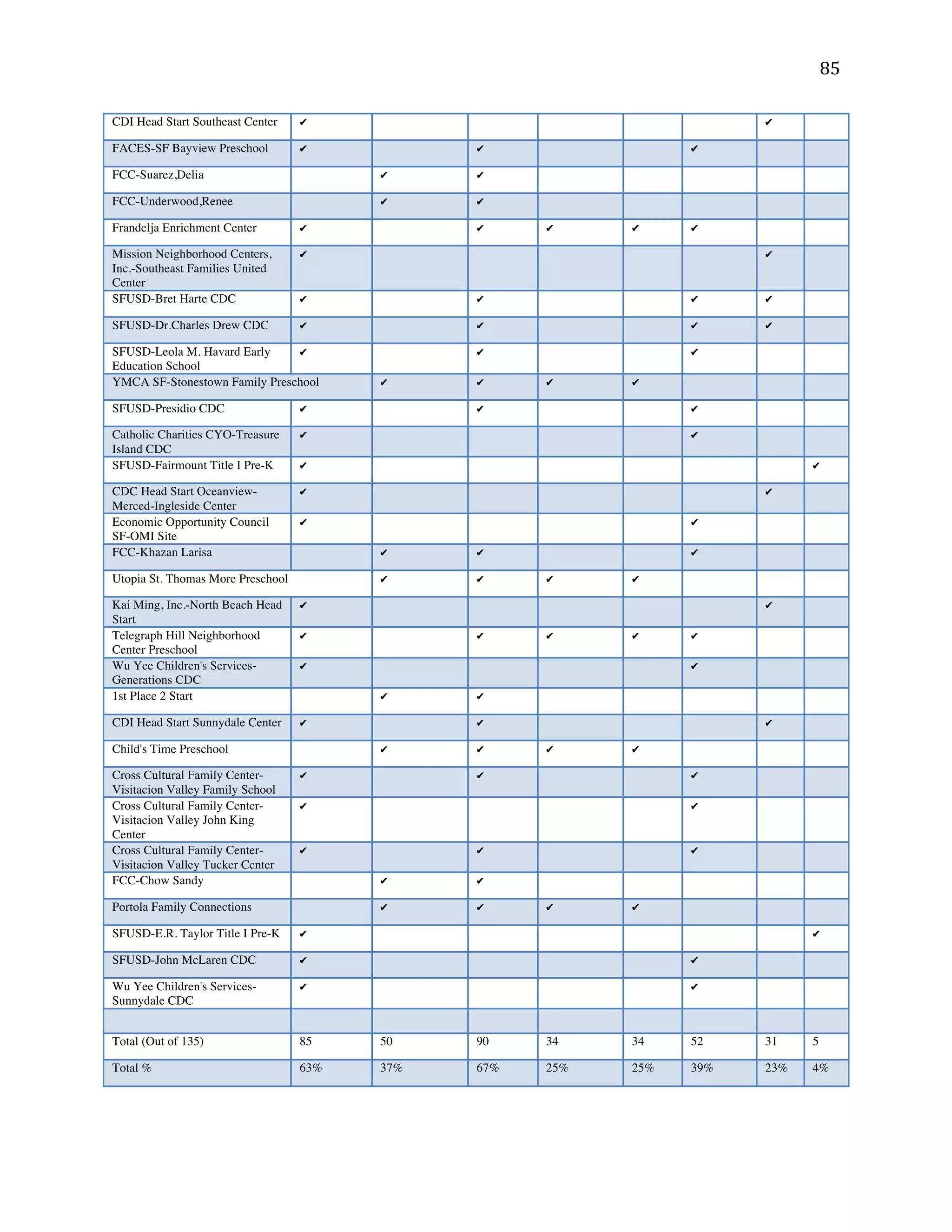

This honors thesis examines preschool policy in California with a focus on increasing access to quality preschool programs. It provides an overview of arguments for and against preschool expansion. It also describes the current mixed market for preschool programs in California, which includes both public and private options of varying quality. The paper uses San Francisco's Preschool For All initiative as a case study to analyze how a universal preschool policy can increase access, particularly for low-income families, without compromising program quality. The thesis aims to identify policy approaches that could help ensure all children in California have access to quality preschool.