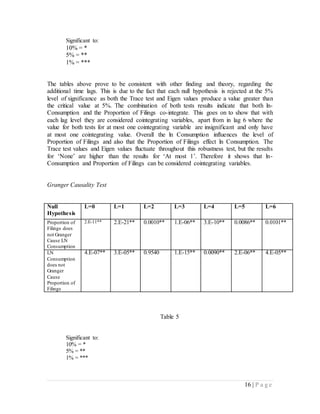

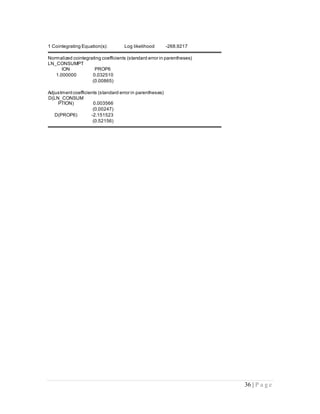

This document is a 5960 word independent study report that examines whether the proportion of Chapter 7 to Chapter 13 bankruptcy filings in the USA influences consumption levels. It contains an introduction outlining the research question, a literature review of previous related studies, a description of the economic framework and methodology, an analysis of the results, and conclusions. The key findings are that a significant positive correlation was found between a state's proportion of bankruptcy filings and its consumption per capita, providing evidence that a higher proportion of Chapter 7 filings may be beneficial to a state's economy.