This document summarizes a research project on how staff at the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program perceive breastfeeding and their clients. The author conducted participant observation and interviews at a local WIC office. Through this research, the author found that WIC staff see breastfeeding as the healthiest option for mothers and infants. However, they also recognize many clients lack confidence in breastfeeding. Therefore, WIC staff provide education and support to encourage breastfeeding while still respecting other feeding choices. This research provides insight into how WIC staff view their clients and how their work promotes breastfeeding to address low rates, especially among low-income families.

![Daugherty 21

person, and check-in via telephone to make sure breastfeeding mothers feel comfortable and

knowledgeable with their choice. However, perhaps more importantly, because Paula herself is a

former breastfeeding WIC client, she can empathize with “her girls” and be the supportive figure

they need. This is made very clear by all the participants, as Marie says:

“If [Paula] doesn’t have a mom in her office, where she’s like trying to teach her how to

get the baby to latch, or different ways to help the mom, she’s counseling them over the

phone, and, I mean it, it builds their confidence and makes them feel more comfortable.

And if they have issues, they have a mom that’s been there, been through it with six kids

and she kind of puts them at ease…”

Paula is there when clients’ families and friends are not, and even when they are to provide that

extra help and support.

Several of the pamphlets Paula had on hand reflect her role, and WIC’s role, as a

supportive entity for breastfeeding mothers. Three pamphlets give information about

breastfeeding support groups and classes sponsored by WIC, and list the phone numbers of Paula

and other lactation consultants, extolling mothers to call with any sort of question. In addition,

the pamphlets themselves inherently provide support; because the educational pamphlets are

designed to be taken home and to alleviate mothers’ worries, they represent WIC’s support of

mothers even when mothers are not physically at WIC. It is clear that WIC’s policy of education

and support represents a goal to enable women to make informed, safe, and healthy decisions for

themselves and their families.

My theoretical framework, the critical paradigms, explains how the lack of confidence

WIC addresses is partially a result of the lower socio-economic status of WIC clients. Because of

their social class, these women are exposed to systems that discourage them from breastfeeding.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a67514b4-32ae-4edd-ad45-199dee3bb660-160410115403/75/FINAL-PAPER-21-2048.jpg)

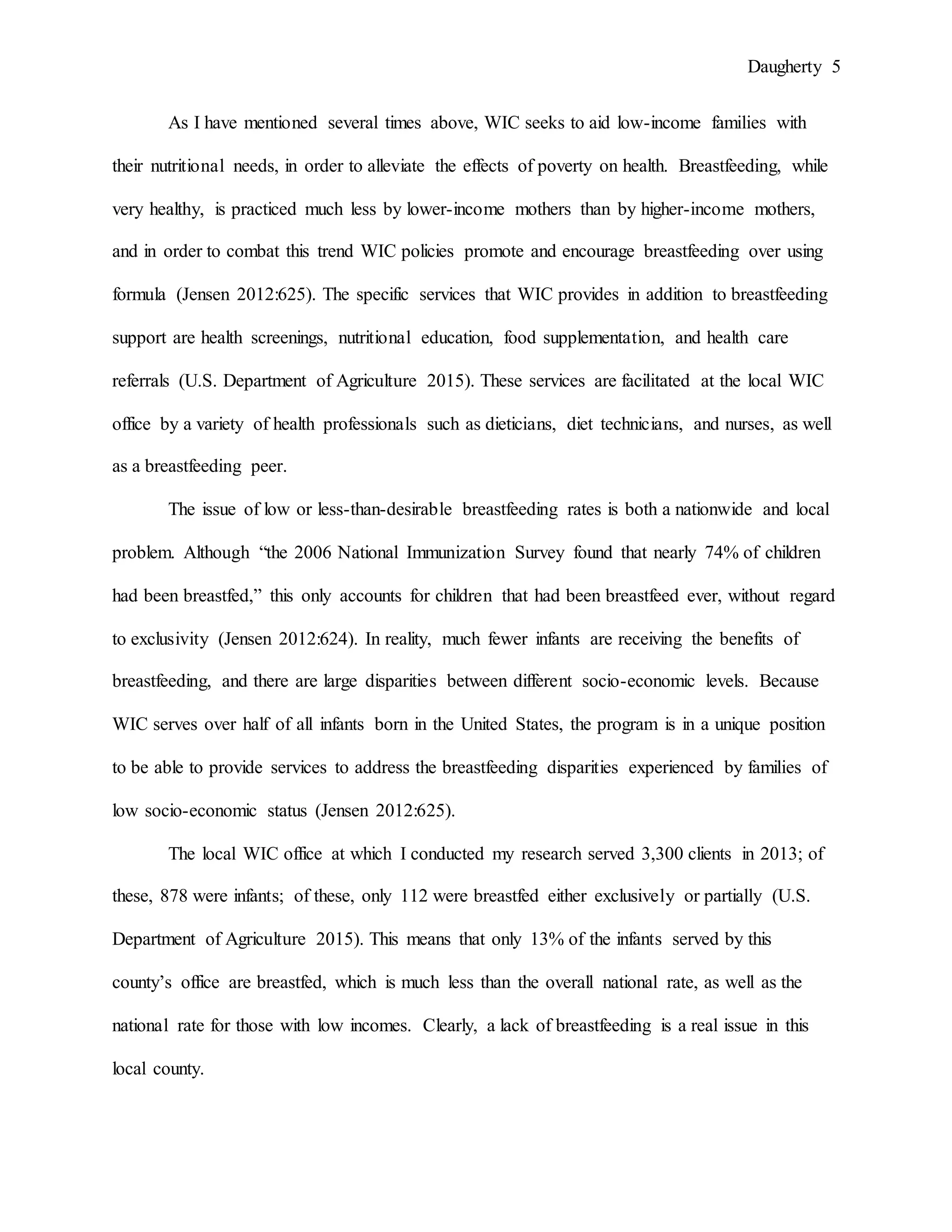

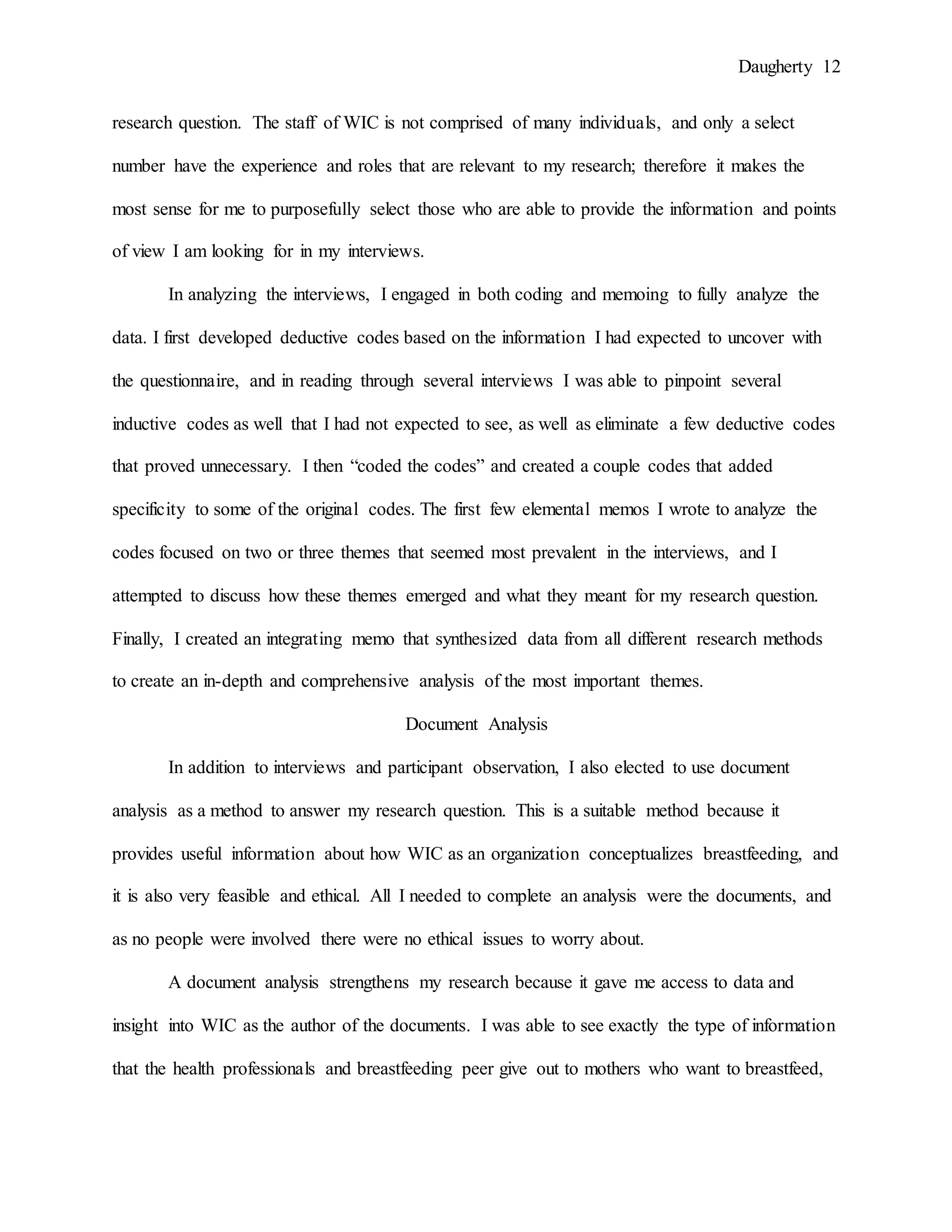

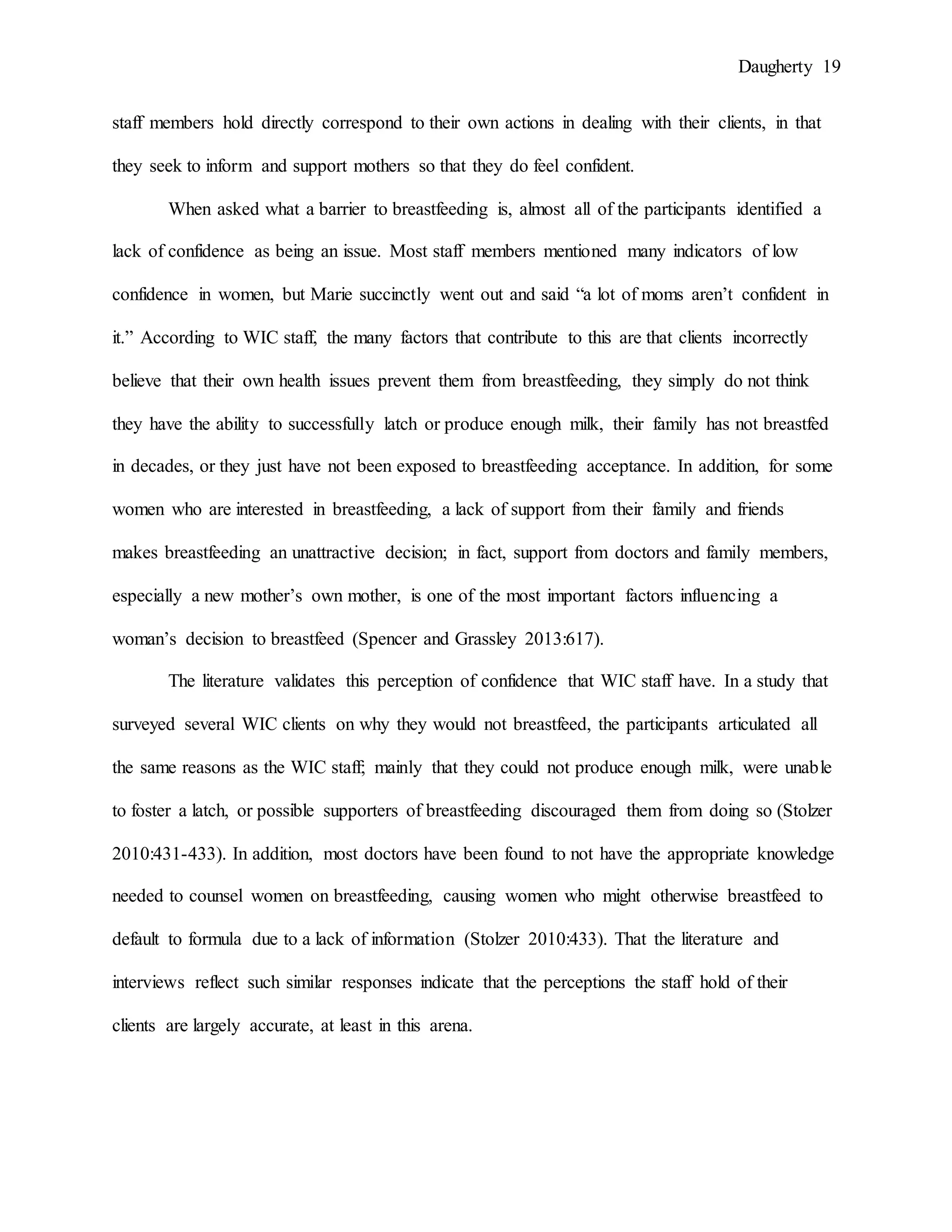

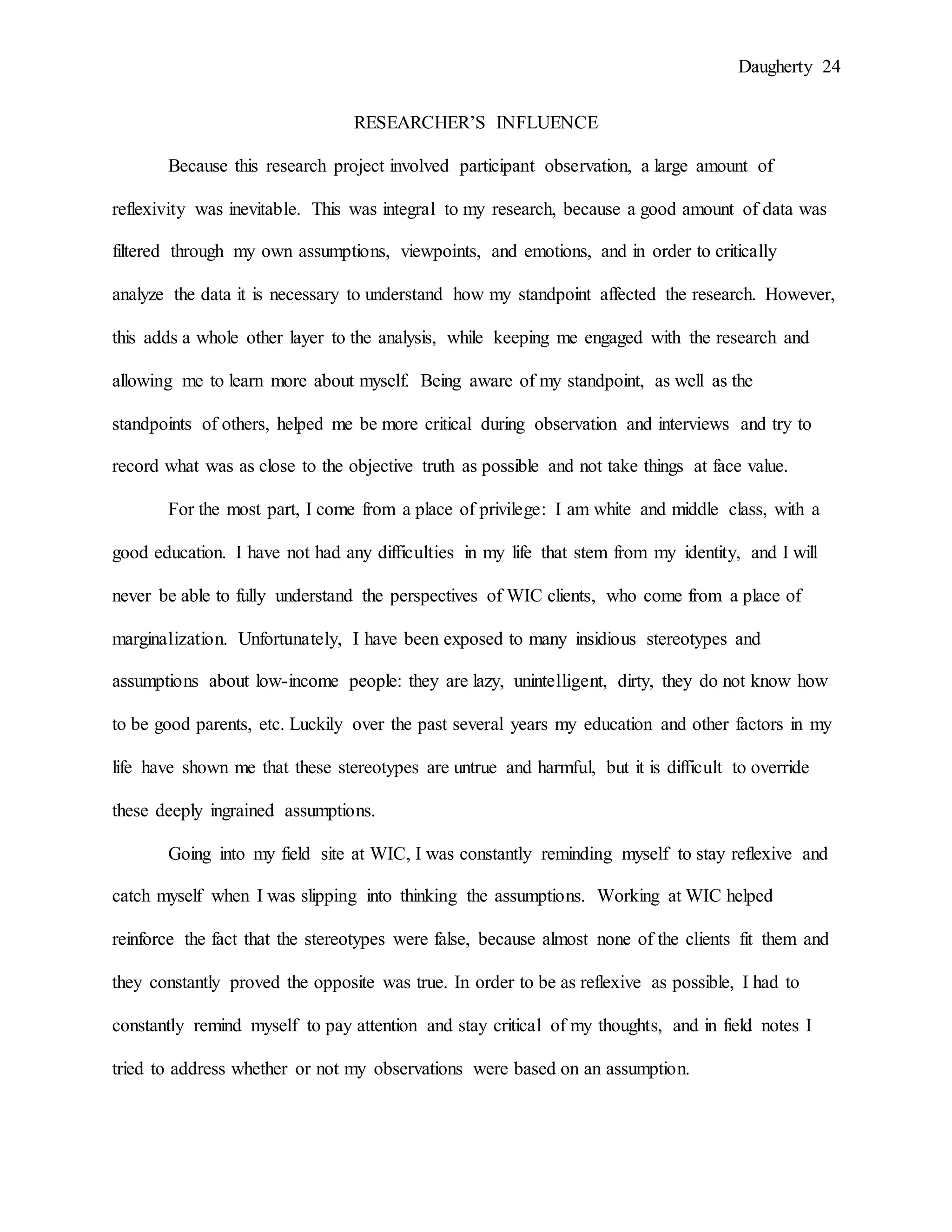

![Daugherty 27

● If one of your clients expressed that they were not interested in breastfeeding, how would

you respond?

○ Are there any sort of institutional regulations or suggestions that encourage you to

convince mothers to breastfeed?

○ Are there any services available for those who decide not to breastfeed?

○ How does your role differ when a mother decides to breastfeed and when she

decides not to?

● What role does WIC’s breastfeeding policy play in advising clients?

○ How do you feel about these policies?

○ Do you think the recent [2009] package changes to promote breastfeeding have

made a difference?

○ Are these changes ethical?

● How has Robin’s role as the breastfeeding peer impacted the experiences of new mothers

who receive WIC benefits?

○ Overall has she had a positive impact, a negative impact, or no impact on these

clients?

○ Overall has she had a positive impact, a negative impact, or no impact on the WIC

office as a whole?

○ In your opinion does Robin represent new mothers, or governmental requirements

in Ohio in her support of breastfeeding?

● How do you feel about having the opportunity to engage personally with clients and

children daily?

○ What are some of the rewarding aspects of talking to clients everyday?

○ Do you enjoy working for the WIC program?

● What are some of the most important governmental requirements the local county WIC

office is required to adhere to?

○ Which of these requirements do you feel are necessary?

○ Do you find any of these requirements frustrating?

○ Which of these requirements do you find unnecessary to the overall achievement

of WIC’s goals?

○ Has your need to stick to these requirements had any impact, either positive or

negative, on a personal interaction with a client?

● Do you think the eligibility requirements for receiving WIC benefits are reasonable?

○ Why?

○ If not, how would you change them?

● If you could change one thing about the way your WIC office is run from a governmental

standpoint what would it be?

○ What are some problems you face daily that are a result of federal requirements?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/a67514b4-32ae-4edd-ad45-199dee3bb660-160410115403/75/FINAL-PAPER-27-2048.jpg)